Introduction

Many Indo-Pacific nations have responded to China's growing willingness to exert its influence in the region and globally1—as well as to the perception that the United States' commitment to the region may be weakening. In part those actions have fostered developing new strategies to strengthen their geopolitical position independent of the United States.2 Regional states have been concerned about numerous Chinese actions, including its extensive military modernization, its more assertive pursuit of maritime territorial claims and efforts to control international or disputed waters, placement of military assets on artificial islands it has created in the South China Sea, efforts to suppress international criticism or pushback through coercive diplomatic or economic measures, and its expanding global presence, including its military base at Djibouti.

Economic dynamics may also be playing a role in governments' policymaking, as economic interdependence between China and virtually all its neighbors remains very strong, and the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) may further deepen trade and investment links between China and regional states. That increased economic interdependence, coupled with China's increasing assertiveness and willingness to use economic levers for political reasons, may be heightening Indo-Pacific nations' strategic mistrust of Beijing. Other shifts affecting the geostrategic balance in the region include the rise of North Korea as a nuclear power, Japan's nascent reacquisition of power projection capabilities, and the introduction of new military technologies (e.g., drones, anti-ship missiles) that appear to challenge traditional elements of military power, which could potentially erode U.S. (and other large military powers') traditional military advantages.

Indo-Pacific nations recently appear to be accelerating the adoption of hedging strategies, at least in part because of the Trump Administration's perceived retreat from the United States' traditional role as guarantor of the liberal international order.3 Understanding these strategies may be important for Congress as it addresses U.S. diplomatic, security, and economic interests in the region and exerts oversight over the Trump Administration's policies towards U.S. allies and partners.

The Trump Administration has sent conflicting signals about its posture in Asia. The Administration's 2018 National Defense Strategy emphasizes the need to "Strengthen Alliances and Attract New Partners." In addressing the need to "expand Indo-Pacific alliances and partnerships" the document states, "We will strengthen our alliances and partnerships in the Indo-Pacific to a networked security architecture capable of deterring aggression, maintaining stability, and ensuring free access to common domains … to preserve the free and open international system."4 Similarly, the Department of Defense Indo-Pacific Strategy Report: Preparedness, Partnerships, and Promoting a Networked Region of June 2019 calls for a "more robust constellation of allies and partners."5 In an address to the U.S. Naval Academy in August 2019, Secretary of Defense Mark Esper described the Indo-Pacific as "our priority theater" and stated

… allies and partners want us to lead … but to do that we must also be present in the region.… Not everywhere, but we have to be in the key locations. This means looking at how we expand our basing locations, investing more time and resources into certain regions we haven't been to in the past.6

Counter to these statements' emphasis on allies and partners, however, the Trump Administration has appeared to some less-engaged on regional issues, sending lower-level officials to key regional summits, withdrawing from the proposed Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) trade agreement, and canceling joint exercises with South Korea. In addition, President Trump has openly questioned the value many of the United States' alliance relationships, particularly with Japan and South Korea. As a result, some observers note that U.S. allies and partners also may be increasingly concerned over aligning too closely with the United States at a time when the United States' commitment to the region is questioned, even as many in the region hope that the United States continues to play a dominant or balancing role in Asia.7 For many in Asia, the strategic picture has been complicated further by the Trump Administration's trade policies, which are sometimes perceived as asking partners to choose between the United States and China—both critical trade and investment relationships that have been crucial to their economic successes over the past few decades.

In response to these developments, some allies and partners are expanding their defense budgets, embarking on major arms purchases, and looking to create new defense and security networks to strengthen their collective ability to maintain their independence from Chinese influence.8 Within this evolving context, regional states are adjusting their strategic calculations. A number of trends appear to be emerging across the Indo-Pacific:

- Several regional states have sought to develop new intra-Asian security partnerships to augment and broaden existing relationships. Japan, Australia, and India are among the most active in this regard;9

- Numerous Asian states have adopted an "Indo-Pacific" conception of the region, strategically linking the Indian and Pacific Ocean regions. However, the concept remains vague and not all states agree on what it means;

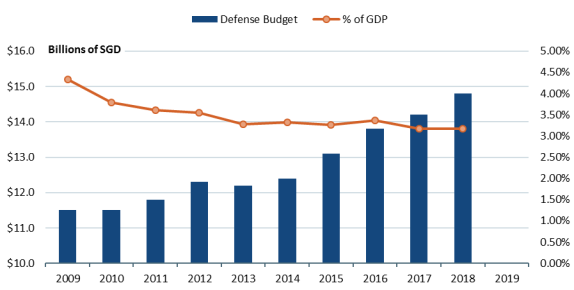

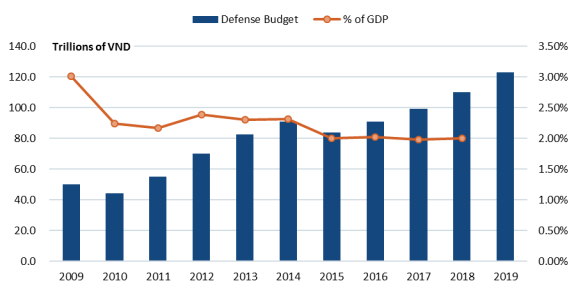

- Many regional states have increased defense spending, although spending as a percentage of GDP has been relatively steady, and some have adopted more outward-looking defense strategies.

Congress has sought to address questions about whether these developments present the United States with challenges and/or opportunities to promote U.S. interests in the Indo-Pacific, and to assess the efficacy of the Trump Administration's strategy towards the region. Some Members of Congress have also sought to demonstrate Congress's commitment to maintaining and expanding both alliance and other relationships in the Indo-Pacific.

In December 2018, for instance, the 115th Congress passed, and President Trump signed into law, the Asia Reassurance Initiative Act of 2018 (ARIA; P.L. 115-409), which provides a broad statement of U.S. policy for the Indo-Pacific region and establishes a set of reporting requirements for the executive branch regarding U.S. policy in the region. ARIA emphasizes the need to "expand security and defense cooperation with allies and partners" and to "sustain a strong military presence in the Indo-Pacific region." It states that "Without strong leadership from the United States, the international system, fundamentally rooted in the rule of law, may wither.... It is imperative that the United States continue to play a leading role in the Indo-Pacific."

In addition to numerous pieces of legislation aimed at addressing challenges associated with China,10 the 116th Congress has also introduced numerous pieces of legislation that seek to emphasize U.S. commitment to the region, including to U.S alliances and partnerships, and to guide U.S. policy. Relevant legislation includes:

- S. 2547—Indo-Pacific Cooperation Act of 2019;

- S.Res. 183—Reaffirming the vital role of the United States-Japan alliance in promoting peace, stability, and prosperity in the Indo-Pacific region and beyond, and for other purposes;

- H.Res. 349—Reaffirming the vital role of the United States-Japan alliance in promoting peace, stability, and prosperity in the Indo-Pacific region and beyond;

- S.Res. 67—Expressing the sense of the Senate on the importance and vitality of the United States alliances with Japan and the Republic of Korea, and our trilateral cooperation in the pursuit of shared interests;

- H.Res. 127—Expressing the sense of the House of Representatives on the importance and vitality of the United States alliances with Japan and the Republic of Korea, and our trilateral cooperation in the pursuit of shared interests;

- S. 985—Allied Burden Sharing Report Act of 2019;

- H.R. 2047—Allied Burden Sharing Report Act of 2019; and

- H.R. 2123—United States-India Enhanced Cooperation Act of 2019.

|

|

Source: Map prepared by Hannah Fischer and Amber Wilhelm with CRS. Notes: There are different definitions of the geographic scope of the Indo-Pacific region. |

Japan

Indo-Pacific Vision and Strategic Context

Since Prime Minister Shinzo Abe delivered a speech before the Indian Parliament in 2007 during his first term, Japan has been at the forefront of promoting the concept of the Indian Ocean and Pacific Ocean regions as a single strategic space. Japan is driven, among other things, by its fear of China's increasing power and influence in the region. Although Sino-Japanese relations have stabilized in 2018 and 2019 following several years of heightened tensions, Tokyo's security concerns about China's intentions have been exacerbated by a territorial dispute over a set of islands in the East China Sea (known as the Senkakus in Japan and the Diaoyutai in China), where China has sought over the past decade to press its claims through a growing civilian and maritime law enforcement presence. Abe is reportedly anxious to establish a regional order that is not defined by China's economic, geographic, and strategic dominance, and has sought new partners who can offer a counterweight to China's clout. Expanding the region to include the South Asian subcontinent—some claim that Abe himself coined the concept of the "Indo-Pacific"—broadens the strategic landscape.

Japan's insecurity is heightened by perceptions that the United States may be a waning power in the region. Japan wants the United States to remain a dominant presence, and the Trump Administration's Free and Open Indo-Pacific formulation asserts that the United States must demonstrate leadership and stay engaged.11

Japan's Free and Open Indo-Pacific strategy differs from the U.S. formulation in some ways, particularly in how the region is defined geographically. Tokyo has a broader view of the Indo-Pacific, encompassing not just the Indian Ocean but extending to the east coast of Africa12 while the U.S. concept does not. Japan and India are working together to develop an Asia Africa Growth Corridor (AAGC), which seeks to coordinate their efforts with other countries to develop regional economic linkages, connectivity, and networks between Asia and Africa. (The AAGC is also a component of the India Japan Joint Vision 2025 for the Indo-Pacific Region, a joint statement signed by the leaders of Japan and India in 2018 to deepen defense cooperation and to facilitate the sale of defense equipment from Japan to India.13) Because of constitutional limitations on Japan's military, Tokyo's Indo-Pacific focus is on infrastructure improvement, trade and investment, and governance programs, another key difference from the Trump Administration's Indo-Pacific strategy, which includes significant military and security elements.14

Despite legal limitations, the Abe government is seeking to increase its security cooperation as part of its Indo-Pacific strategy. In December 2018, Japan released a pair of documents that are intended to guide its national defense efforts, including the defense budget, over the next decade—the National Defense Program Guidelines for FY2019 and Beyond15 and the Medium Term Defense Program (FY2019-FY2023).16 With concerns over China and North Korea at their heart, the guidelines layout a continued dual strategy of strengthening Japan's own defense program while also strengthening security cooperation with the United States and other countries.

The 2019 National Defense Program Guidelines show stark shifts in content from previous iterations. Importantly, the document emphasizes Japan's own defense efforts independent of the security cooperation with the United States, stating upfront that as a matter of national sovereignty "Japan's defense capability is the ultimate guarantor of its security and the clear representation of the unwavering will and ability of Japan as a peace-loving nation."17 The document calls for enhancing Japan's capabilities in traditional security domains (land, air, and sea), such as with increasing the use of unmanned vehicles and operationally flexible Short Take-Off and Vertical Landing (STOVL) fighter aircraft. It also highlights the importance of "new domains" such as cyber, space, and the electromagnetic spectrum. Overall, Japan aims for efforts with the United States to remain on a similar trajectory as the past, but it places more emphasis on cooperation with Australia and India, and less with South Korea.

Relations with the United States

Japanese leaders—particularly Prime Minister Shinzo Abe—have deepened defense cooperation with the United States for the past two decades as part of their efforts to ensure China does not become a regional hegemon. Among Abe's efforts to strengthen the alliance are updating the bilateral defense guidelines, re-interpreting a constitutional clause to allow for collective self-defense activities, pushing legislation through the Japanese parliament to allow for broader engagement with the United States, and pressing for the construction of a controversial U.S. Marine air base in Okinawa.

Japan continues to put its alliance with the United States at the center of its security strategy, despite some significant differences with U.S. foreign policy under the Trump Administration that could threaten Tokyo's desire to keep the United States engaged in the region. Many in Japan are anxious that President Trump's approach to dealing with North Korea may marginalize Tokyo's primary concerns with North Korea's short and medium-range missile capabilities and the fate of several Japanese nationals abducted by North Korean agents in the 1970s and 1980s. Japan has also expressed disappointment with the U.S. decision to withdraw from the Paris Climate Accord. Japan was also dismayed at the U.S. decision to withdraw from the TPP in 2017. Japan views the multilateral trade agreement as a fundamental element of its Indo-Pacific strategy, and led the effort to salvage the agreement, now known as the TPP-11 (or as the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for the Trans-Pacific Partnership, or CPTPP). The pact entered into force at the end of 2018.

Although Japan reached a limited trade agreement with the United States in 2019, it received no assurance that the Trump Administration will not impose tariffs on its auto industry. In 2020 Japan is due to re-negotiate its burden sharing arrangement that offsets the cost of stationing U.S. military forces on its territory and anticipates that the Trump Administration will demand a significant increase in Japan's contribution.

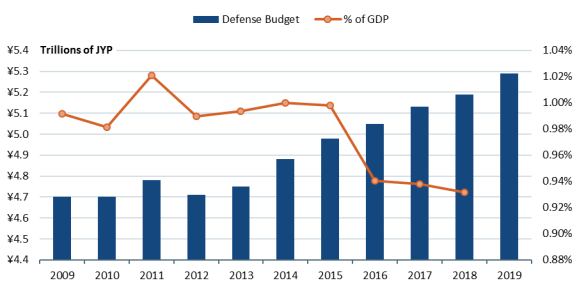

Defense Spending

Japan's supplementary 2019 Medium Term Defense Program lays out a detailed picture of intended activities. The Program projects a five-year expenditure plan that would cost ¥27,470 billion (about US$250 billion18), although it also suggests the annual defense budget target would be ¥25,500 billion, or US$232 billion.

The 2019 Medium Term Defense Program indicates that the majority of the increased budget will be spent on more up-to-date weapons technology, such as the continued replacement of old F-15 jets with F-35As and the introduction of STOVL F-35s. Another major expense is plans to procure a new type of destroyer and to retrofit one of their current destroyer-class vessels (Izumo-class helicopter carrier) with capabilities to accommodate the STOVL aircraft. Further, the program calls for the procurement of a variety of missiles and missile-defense systems. In this area Japan has already agreed to expand its Aegis ballistic missile defense systems at a reported cost of $2.15 billion19, announced plans to build new medium- and long-range cruise missiles20, and agreed to a much smaller purchase joint strike missiles that will give it land-attack capabilities from the air for the first time.21 These advanced systems enhance Self Defense Forces (SDF, Japan's name for its military) capabilities and underscore Japan's commitment to shoulder more of its security needs instead of relying on U.S. protection. The Program calls for "reorganization of the major SDF units," and personnel levels are expected to increase by about three percent since the 2000s.

Emerging Strategic Relationships

Japan's defense relationships with countries other than the United States are less developed but Japan is actively working to expand its security partnerships beyond the United States. Some analysts suggest these efforts reflect concern about the durability of the U.S. alliance and a general need to diversify security partners.22

Australia

Ties with Australia have become increasingly institutionalized and regular. Australia is Japan's top energy supplier, and a series of economic and security pacts have been signed under Abe, including a $40 billion gas project, Japan's biggest ever foreign investment.23 In 2007, the two nations reached agreement on a Joint Declaration on Security Cooperation,24 and in 2017, Tokyo and Canberra signed an updated acquisition and cross-servicing agreement (ACSA).

As another U.S. treaty ally, Australia uses similar practices and equipment, which may make cooperation with Japan more accessible. Although Japan had some difficult World War II history with Australia,25 Abe himself has made efforts to overcome this potential obstacle to closer defense ties. In 2014, during the first address to the Australian parliament by a Japanese Prime Minister, Abe explicitly referenced "the evils and horrors of history" and expressed his "most sincere condolences towards the many souls who lost their lives."26 In 2018, Abe visited Darwin, the first time a Japanese leader visited the city since Imperial Japanese forces bombed it during World War II. In 2018, Japan and Australia "reiterated their determination to work proactively together and with the United States and other partners to maintain and promote a free, open, stable and prosperous Indo-Pacific founded on the rules-based international order."27 Despite advancements, Canberra and Tokyo do have some differences; for example they have struggled to conclude a visiting forces agreement over a variety of concerns, including Japan's adherence to the death penalty, which could mean that an Australian soldier convicted of a heinous crime could face a death sentence, which contravenes Australia's legal system.28

India and the "Quad"

The concept of the Free and Open Indo-Pacific is particularly appealing to Japan because of its strong relationships with India and Australia, and Abe has pursued cooperation with these maritime democracies and the United States as part of the "quad" grouping. During Abe's first stint as Prime Minister in 2006-2007, he pursued tighter relations with India, both bilaterally and as part of his "security diamond" concept. Under Abe and Prime Minister Narendra Modi, interest in developing stronger ties intensified, and the two countries have developed more bilateral dialogues at all levels of government, supported each other on areas of mutual concern, and bolstered educational and cultural exchanges.

Analysts point to mutual respect for democratic institutions, as well as shared strategic and economic interests, that have allowed the relationship to flourish. Japan and India—both of which have long-standing territorial disputes with China—have sought to increase their bilateral cooperation in apparent response to alarms raised by China's actions over the past decade perceived as too assertive or even aggressive. Japanese companies have made major investments in India in recent years, most notably with the $100 billion Delhi-Mumbai Industrial Corridor project, and Japanese investment already plays a central role in providing regional alternatives to China's BRI. In October 2018 Prime Ministers Abe and Modi reaffirmed their commitment to bilateral economic and defense cooperation at the 13th annual India Japan Summit. Japan and India have expanded joint military exercises to include army and air force units in addition to the annual Malabar naval exercise.29

Many analysts see engaging India in a broader security framework as the primary challenge to establishing a quadrilateral arrangement. The United States has treaty alliances with both Japan and Australia, and Japan and Australia have also developed a sophisticated security partnership in the past decade. India, however, appears to have been more reluctant to sign on to international commitments from its legacy as a "non-aligned movement" state and is more reluctant to antagonize Beijing.30

The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN)

Japan has maintained a consistent level of economic and diplomatic engagement with ASEAN countries for several decades. Although more limited, Japan also has expanded the security dimension of its relationships with several Southeast Asian countries under Abe's stewardship. Maritime security has been a particular focus with Vietnam, the Philippines, and Malaysia. Japan has participated in a multitude of regional fora that address maritime issues and has deployed its Coast Guard to work with ASEAN countries. Japan promotes cooperation and provides resources to address anti-piracy, counter-terrorism, cyber security, and humanitarian assistance and disaster response in Southeast Asia.

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO)

Japan also has sought to deepen ties with the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). Japan is considered NATO's longest standing partner outside of Europe, and recently has participated in exercises in the Baltic Sea with the Standing NATO Maritime Group One.31 With an emphasis on maritime security, Japan participates in the Partnership Interoperability Platform (which seeks to develop better connectivity between NATO and partner forces), provides financial support for efforts to stabilize Afghanistan, and takes part in assorted other NATO capacity building programs.32

India

Indo-Pacific Vision and Strategic Context

New Delhi broadly endorses the Free and Open Indo-Pacific strategy pursued by Washington, and India benefits from the higher visibility this strategy provides for India's global role and for its immediate region. Despite its interest in working more closely with the United States, India has not fully relinquished the "nonalignment" posture it maintained for most of the Cold War (more recently pursuing "strategic autonomy" or a "pragmatic and outcome-oriented foreign policy"33). It continues to favor multilateralism and to seek a measure of balance in its relations with the United States and neighboring China. New Delhi sees China as a more economically and militarily powerful rival, and is concerned about China's growing presence and influence in South Asia and the Indian Ocean region. Thus, Prime Minister Modi has articulated a vision of a free, open, and inclusive Indo-Pacific, and India has engaged Russia, Japan, Australia, and other Indo-Pacific countries as potential balancers of China's influence while remaining wary of joining any nascent security architectures that could antagonize Beijing. While India endorses the United States' Free and Open Indo-Pacific strategy, its own approach differs in significant ways.

[I]t gives equal emphasis to the term 'inclusive' in the pursuit of progress and prosperity, including all nations in this geography and "others beyond who have a stake in it"; it does not see the region as a strategy or as a club of limited members; it does not consider such a geographical definition as directed against any country; nor as a grouping that seeks to dominate.34

Some observers have described India's foreign policy under Modi as having new dynamism as India seeks to transform its Look East policy into an Act East policy.35 The inaugural Singapore-India-Thailand Maritime Exercise (SITMEX) was held in the Andaman Sea in September 2019 and has been viewed by observers as "a tangible demonstration of intra-Asian security networking."36 By some accounts, India is poorly suited to serve as the western anchor of the Free and Open Indo-Pacific, given its apparent intention to maintain strategic autonomy, and its alleged lack of will and/or capacity to effectively counterbalance China. Moreover, many in India consider a Free and Open Indo-Pacific conception that terminates at India's western coast (as the Trump Administration's conception appears to do) to be "a decidedly U.S.-centric, non-Indian perspective" that omits a huge swath of India's strategic vista to the west.37

Relations with the United States

Most analysts consider that the Modi/BJP victory in spring 2019 parliamentary elections has empowered the Indian leader domestically and on the global stage.38 Given Modi's reputation for a "muscular" foreign policy, this could lead to a greater willingness to resist Chinese assertiveness and move closer to the United States while not abandoning multilateral approaches.39 Yet challenges with the United States loom: many Indian strategic thinkers say their country's national interests are served by continued engagement with Russia and Iran, and thus contend there will be limits to New Delhi's willingness to abide "America's short-term impulses."40 While New Delhi generally welcomes the U.S. Free and Open Indo-Pacific strategy, Indian leaders continue to demur from confronting China in most instances.41

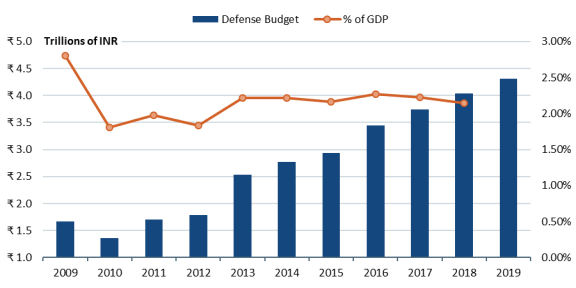

Defense Spending

Since 2009, India's budget has grown at an average annual rate of 9%. However, as a percentage of the country's GDP, defense expenditures have decreased. More than half (51%) of India's 2019-2020 defense budget is allocated for salaries and pensions, including 70% for the Indian Army. While military modernization efforts continue, they are not taking place at the rate called for by many Indian defense analysts. Much of the country's defense equipment falls into the "vintage" category, including more than two-thirds of the Army's wares.42 Over the past decade capital outlays (which include procurement funds) have declined as a proportion of the total defense budget. This decline has contributed to a slowing of naval and air force acquisitions, in particular, and a continued heavy reliance on defense imports (about 60% of India's total defense equipment is imported, the bulk from Russia).43 Stalled reforms in the defense sector have delayed modernization efforts, which some analysts say are already hampered by ad hoc decision making and a lack of strategic direction. In the words of one senior observer, "In fact, it is India's dependence on arms imports—and their corrupting role—that are at the root of the Indian armed forces' equipment shortages and the erosion in the combat capabilities."44 New Delhi seeks to diversify its defense suppliers, recently making more purchases from Israel and the United States, among others.

Emerging Strategic Relationships

India is pursuing bilateral relations with Japan and Australia in a manner largely consistent with the strategic objectives of the Trump Administration's Free and Open Indo-Pacific strategy, while India's bilateral relations with China, Russia and Iran could present challenges for that strategy. Despite India's interest in engaging with other regional powers in the Indo-Pacific, the 2019 Modi/BJP election win is expected to see a continuation of New Delhi's multilateralist approach to international politics in Asia, continuing to pursue stable relations with all powers, including China and Russia. India is a full member of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), a regional grouping that also includes China, Russia, Pakistan and several Central Asian nations,45 and conducts regular trilateral summits with China and Russia. It has been resistant to outright confrontation with Beijing, even as it resists Chinese "assertiveness" in South Asia.46

Japan and Australia

India's deepening "strategic partnership" with Japan is a major aspect of New Delhi's broader "Act East" policy and is a key axis in the greater Indo-Pacific strategies broadly pursued by all three governments now participating in a newly established U.S.-Japan-India Trilateral Dialogue. U.S., Indian, and Japanese naval vessels held unprecedented combined naval exercises in the Bay of Bengal in 2007, and trilateral exercises focused on maritime security continue. India-Australia defense engagement is underpinned by the 2006 Memorandum on Defence Cooperation and the 2009 Joint Declaration on Security Cooperation. India and Australia also develop their maritime cooperation through the AUSINDEX biennial naval exercise.47

China

India's relations with China have been fraught for decades, with signs of increasing enmity in recent years. Areas of contention include major border and territorial disputes, China's role as Pakistan's primary international benefactor, the presence in India of the Dalai Lama and a self-described Tibetan "government," and China's growing influence in the Indian Ocean region, which Indians can view as an encroachment in their neighborhood. New Delhi is ever watchful for signs that Beijing seeks to "contain" Indian influence both regionally and globally. China's BRI—with "flagship" projects in Pakistan—is taken by many in India as an expression of Beijing's hegemonic intentions.48 Despite these multiple areas of friction in the relationship, China is India's largest trade partner, and New Delhi's leaders are wary of antagonizing their more powerful neighbor and emphasize an "inclusive" vision for the Indo-Pacific region. There is cooperation on some issues, including on global trade and climate change. A mid-2018 summit meeting in Wuhan, China, was seen as a mutual effort to reset ties and "manage differences through dialogue;" this "Wuhan spirit" was carried into a subsequent informal summits, the most recent held in Chennai, India, in October 2019.49

Russia

India maintained close ties with Russia throughout much of the Cold War, and it continues to rely on Russia for the bulk of its defense imports, as well as significant amounts of oil and natural gas. With the 2017 enactment of the Countering America's Adversaries Through Sanctions Act (CAATSA, P.L. 115-44), India's continued major arms purchases from Russia—most prominently a multi-billion-dollar deal to purchase the Russian-made S-400 air defense system—could trigger U.S. sanctions.50

Iran

India has also had historically friendly relations with Iran, a country that lately has supplied about 10-12% of India's energy imports.51 It also opposes Tehran's acquisition of nuclear weapons and supports the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action. Historically averse to unilateral (non-UN) sanctions, New Delhi until recently enjoyed an exemption from U.S. efforts targeting Iran's energy sector. In April 2019, the Trump Administration announced an end to such exemptions, and India is reported to have fully ceased importation of Iranian oil in early May, while informing Washington that the move "comes at a cost."52 New Delhi considers its $500 million investment in Iran's Chabahar port crucial to India's future trade and transit with Central Asia (the project is exempt from U.S. sanctions53).

Australia

Indo-Pacific Vision and Strategic Context

Australia is responding to increasing geopolitical uncertainty and the rise of China in the Indo-Pacific region by maintaining a strong alliance relationship with the United States, increasing defense spending,54 purchasing key combat systems from a variety of suppliers, 55 and seeking to develop strategic partnerships with Japan, India and others.

Australia, situated between the Indian and Pacific Oceans, increasingly thinks of itself as deeply embedded in the Indo-Pacific region. This is evident in the emphasis on the Indo-Pacific concept in the Australian Government's 2017 Foreign Policy White Paper.56 While Australia's focus early in its history was on its place within the British Empire and the "tyranny of distance" that placed it on the periphery of the world for much of its history,57 it now finds itself situated in a region that has accounted for the majority of global economic growth over the past two decades. Leading Australian strategic thinkers view the Indo-Pacific as a largely maritime, strategic, and geo-economic system "defined by multi-polarity and connectivity … in a globalized world."58 While Australia shares the values of the Free and Open Indo-Pacific concept, and many in Australia are concerned with China's growing influence in Australia, the South Pacific and the Indian Ocean, it is Australia's geography, as well as its broader interests, that are at the core of its Indo-Pacific strategy.

Australian Minister for Defence Linda Reynolds stated:

Australia's Indo–Pacific vision reflects our national character and also our very unique sensibilities. We want a region that is open and inclusive; respectful of sovereignty; where disputes are resolved peacefully; and without force or coercion. We want a region where open markets facilitate the free flow of trade, of capital and of ideas and on where economic and security ties are being continually strengthened. We want an Indo-Pacific that has ASEAN at its heart and is underpinned by the rule of law with the rights of all states being protected. Australia's vision is also one that includes a fully-engaged United States.59

Popular Australian attitudes towards China have changed in recent years. Australian perceptions of China have been shaped, to a large extent, by the economic opportunity that China represents. Revelations regarding China's attempts to influence Australia's domestic politics, universities, and media,60 have negatively influenced Australians' perceptions of China and the Australian government is undertaking a number of measures to counter China's growing influence in the country. On June 28, 2018, the Australian parliament passed new espionage, foreign interference and foreign influence laws "creating new espionage offences, introducing tougher penalties on spies and establishing a register of foreign political agents."61 In August 2018, Australia blocked Chinese telecommunications firm Huawei from involvement in Australia's 5-G mobile network.62

Canberra also has been focused on Chinese political engagement, investment, and influence operations globally, particularly in the Pacific Islands, a region Australia considers strategically important to its own national interest. In responding to reports of China's reported efforts to establish a military presence in Vanuatu, former Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull stated, "We would view with great concern the establishment of any foreign military bases in those Pacific island countries."63 Australia has also been concerned about the impact of Chinese development aid to Pacific island states, which, as tracked by the Australian Lowy Institute Mapping Foreign Assistance in the Pacific project, increased significantly from 2006 to 2016, with cumulative aid commitments totaling $1.78 billion over that period.64 It has responded with a significant policy pivot to step up its own focus on the South Pacific.65 This is demonstrated by a number of recent actions, including Prime Minister Morrison's visit to Vanuatu and Fiji, increased aid from Australia to Pacific island states, and Australia, Papua New Guinea and the United States' joint development of the Lombrum naval facility on Manus Island in Papua New Guinea.66 The Pacific Islands receive 31% of Australia's foreign assistance budget of $3.1 billion.67 Australia, New Zealand, and the United States held an inaugural Pacific Security Cooperation Dialogue in June 2018 "to discuss a wide range of security issues and identify areas to strengthen cooperation with Pacific Island countries on common regional challenges."68

Responding to China's growing influence is a key driver of Canberra's Indo-Pacific strategy, and Australia has taken a number of steps to develop its economic engagement in the Pacific both independently and in coordination with the U.S. and Japan. Australia, Japan and the United States have shared understandings of the need for developing sustainable and economical alternatives to China's Belt and Road geo-economic strategy even as the three nations have somewhat different perspectives on the Free and Open Indo-Pacific concept. By some estimates, there is a need for $26 trillion in infrastructure development in Asia through 2030.69 Australia's 2017 Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) white paper pointed out that:

Even as growth binds the economies of the Indo-Pacific, trade and investment and infrastructure development are being used as instruments to build strategic influence, as well as to bring commercial advantage. In the past, the pursuit of closer economic relations between countries often diluted strategic rivalries. This geo-economic competition could instead accentuate tension.70

Export Finance Australia provides loans, guarantees, bonds, and insurance options to "enable SMEs, corporates and governments to take on export-related opportunities, and support infrastructure development in the Pacific region and beyond."71 In February 2018, the Overseas Private Investment Corporation and Australia's Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade signed a bilateral Memorandum of Understanding on joint infrastructure investment in the Pacific.72 In November 2018, the United States, Australia and Japan moved forward with their coordinated effort to address regional infrastructure needs.

Australia's Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) and Export Finance and Insurance Corporation (Efic), the Japan Bank for International Cooperation (JBIC), and the U.S. Overseas Private Investment Corporation (OPIC) signed a Trilateral Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) to operationalize the Trilateral Partnership for Infrastructure Investment in the Indo-Pacific.… Through the MOU, we intend to work together to mobilize and support the deployment of private sector investment capital to deliver major new infrastructure projects, enhance digital connectivity and energy infrastructure, and achieve mutual development goals in the Indo-Pacific.73

This effort has been described as "an obvious reaction to China's regional ambitions."74 Australia also supports the Pacific Islands Forum, a multilateral organization aimed at enhancing cooperation among Pacific governments.

Relations with the United States

A traditional cornerstone of Australia's strategic outlook is the view that the United States is Australia's most important strategic partner and a key source of stability in the Asia-Pacific region. The ongoing strength of the bilateral defense relationship with the U.S., as well as growing multilateral connections, was demonstrated through the July 2019 Talisman Sabre military exercise that included 34,000 personnel from the U.S. and Australia as well as embedded troops from Canada, Japan, New Zealand and the United Kingdom and observers from India and South Korea.75 In 2018, however, heightened concern emerged in Australia about its relationship with the United States under President Trump's leadership.76 At the same time, Australians' support for the Australia-New Zealand United States (ANZUS) Alliance remains high. A 2019 Lowy Institute poll found that 73% of Australians feel that the alliance with the U.S. "is a natural extension of our shared values and ideals."77 One recent study conducted at the United States Studies Centre at the University of Sydney is concerned that the United States "no longer enjoys military primacy in the Indo-Pacific and its capacity to uphold a favourable balance of power is increasingly uncertain." It recommends that, "A strategy of collective defence is fast becoming necessary as a way of offsetting shortfalls in America's regional military power and holding the line against rising Chinese strength."78

The 2019 Australia-U.S. Ministerial (AUSMIN) consultations "emphasized the need for an increasingly networked structure of alliances and partnerships to maintain an Indo-Pacific that is secure, open, inclusive and rules-based." It also "welcomed a major milestone in the Force Posture Initiatives, as the rotational deployment of U.S. Marines in Darwin has reached 2,500 personnel in 2019. The principals emphasized the value of Marine Rotational Force – Darwin (MRF-D) in strengthening the alliance, and in deepening engagement with regional partners."79 MRF-D was a key project of the Obama Administration's "rebalance to Asia" strategy. Following the 2019 AUSMIN meeting, Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison announced on August 21 that Australia would join the U.S.-led effort to protect shipping in the Strait of Hormuz.80

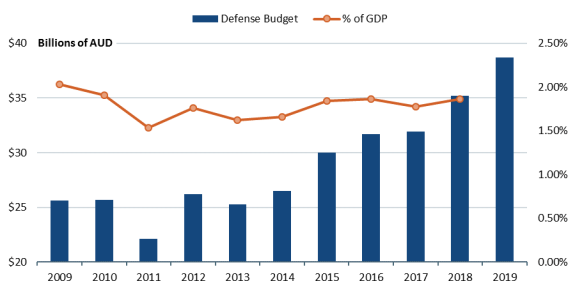

Defense Spending

Australia's budget for 2019-20 focused on building defense by

… enhancing our regional security, building defence capability and supporting Australia's sovereign defence industry.… The Budget maintains the Government's commitment to grow the Defence budget to two per cent of GDP by 2020–21. The Government will allocate Defence [A]$38.7 billion in 2019-20.81

Over the decade to 2028 the Australian government is investing more than A$200 billion in defense capabilities.82 (1A$=0.69US$) This investment includes a number of key weapons systems including the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter, P-8A Poseidon maritime surveillance aircraft, and upgrades to the EA-18G Growler electronic attack aircraft and E-7A Wedgetail battle space management aircraft. The Royal Australian Air Force took delivery of 2 F-35A Joint Strike fighters in December 2018. These are the first of a total of 72 F-35A aircraft ordered by Australia.83 Australia has also moved to acquire nine British BAE Systems designed Hunter class frigates valued at A$35 billion. The purchase of the Hunter class frigates is expected to improve interoperability between the Australian and British navies while enhancing British ties to a Five Power Defence Arrangement (FPDA) partner.84 Australia will also purchase 12 Shortfin Barracuda submarines designed by DCNS of France for A$50 billion.85 Australia is also acquiring 211 Combat Reconnaissance Vehicles86 and unmanned maritime patrol aircraft including the Triton.

Emerging Strategic Relationships

Shifts in the geostrategic dynamics of Asia are leading Australia to hedge, increasingly by partnering with other Asian states, against the relative decline of U.S. engagement in the region. Australian efforts to develop broader security cooperation relationships can be seen in the AUSINDEX exercise between Australia and India, through the Pacific Endeavor naval deployment, which visited India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, Sri Lanka, Thailand and Vietnam, and through the inclusion of Japan in the U.S.-Australia Talisman Sabre exercise for the first time in 2019.87 Increasing numbers of high level visits and joint military exercises between Australia and India point to common concerns "about a rising China and its strategic consequences on the Indo-Pacific strategic order."88 Such developments also mark change in the regional security architecture which has been grounded in the post-war San Francisco "hub-and-spoke" system of U.S. alliances. This shift towards security networks in which middle powers in Asia increasingly rely on each other could build on and complement these states' ties with the United States. In its white paper outlining its strategy for pursuing deeper partnerships in the Indo-Pacific, the government noted,

The Indo–Pacific democracies of Japan, Indonesia, India and the Republic of Korea are of first order importance to Australia, both as major bilateral partners in their own right and as countries that will influence the shape of the regional order. We are pursuing new economic and security cooperation and people-to-people links to strengthen these relationships. Australia will also work within smaller groupings of these countries, reflecting our shared interests in a region based on the principles ... Australia remains strongly committed to our trilateral dialogues with the United States and Japan and, separately, with India and Japan. Australia is open to working with our Indo–Pacific partners in other plurilateral arrangements.89

Another recent example of Australia's efforts to develop new economic and security cooperation with regional states includes Australia's developing relationship with Vietnam. Bilateral trade between Australia and Vietnam grew by 19.4% in 2018 to $7.72 billion.90 Australia and Vietnam officially upgraded their relationship to a "Strategic Partnership" during a visit to Australia by Vietnamese Prime Minister Nguyen Xuan Phuc in March 201891 and Australian naval ships visited Cam Ranh Bay in May 2019 as part of increasing naval cooperation between the two nations. This was followed by a visit by Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison to Vietnam in August 2019. During the official visit, Morrison and Prime Minister Nguyen Xuan Phuc reportedly discussed rising tensions in the South China Sea. At their joint news conference, Phuc stated, "We are deeply concerned about the recent complicated developments in the East Sea (South China Sea) and agree to cooperate in maintaining peace, stability, security, safety and freedom of navigation and overflight."92

European Countries

In recent years, some European countries, particularly France and the United Kingdom (UK), have deepened their strategic posture in the Indo-Pacific. Although both countries remain relatively modest powers in the region, a growing French and British presence can support U.S. interests. Through their strategic relations, arms sales, and military-to-military relationships, France and the UK have the ability to strengthen the defense capabilities of regional states and help shape the regional balance of power. In recent years, France and the UK are networking with like-minded Indo-Pacific nations to bolster regional stability and help preserve the norms of the international system.93 These efforts reinforce the United States' goal of maintaining regional stability by strengthening a collective deterrent to challenges to international security norms. Such challenges include China's construction and militarization of several artificial islands in the South China Sea, its increasingly aggressive behavior in asserting its maritime claims, and the extension of PLA Navy patrols into the Indian Ocean. Additionally, some European countries have dispatched naval vessels to the East China Sea to help enforce United Nations Security Council resolutions against North Korea, providing opportunities for cooperation with the United States and other U.S. partners on other issues, such as the South China Sea.

France

France has extensive interests in the Indo-Pacific region. These include 1.6 million French citizens living in French Indo-Pacific territories and an extensive exclusive economic zone (EEZ) of 9 million square kilometers derived from those territories. France has regional military installations in its territories as well as in Djibouti and the UAE and reportedly sends its warships into the South China Sea.94 In total, about 7,000 French military personnel are deployed to five military commands in the region. France is part of the FRANZ Arrangement with Australia and New Zealand and is a member of the Quadrilateral Defense Coordination Group with Australia, New Zealand, and the United States.

The French Territory of New Caledonia, which voted to remain part of France in a November 4, 2018, referendum, has a population of approximately 270,000 and 25% of the world's nickel reserves. In the lead-up to the referendum, French President Emmanuel Macron stated "in this part of the globe China is building its hegemony … we have to work with China … but if don't organize ourselves, it will soon be a hegemony which will reduce our liberties, our opportunities which we will suffer." Macron reportedly is planning to organize a meeting of Pacific island nations in 2020.95

Although France and the United Kingdom continue to be the European countries with the most far-reaching presence in the Indo-Pacific, some analysts point to several factors that might limit the French government's ability to realize its growing ambitions in the region. These include a crowded strategic environment in which other countries are increasingly vying for regional influence; a domestic climate of weak economic growth and budgetary pressures on defense forces that are carrying out prolonged military operations in Africa and the Middle East, as well as counter-terrorism operations in mainland France; and a continued desire to maintain sound economic and diplomatic relations with China.96

Emerging Strategic Relationships

France has long been engaged in the Indo-Pacific region, but its defense activities have deepened in recent years. It is maintaining existing ties with its territories in the South Pacific and the Indian Ocean while developing strategic relations with key regional states including India, Australia, Japan, and Vietnam.

A number of factors are contributing to France's growing ambitions in the region, including concerns about China's growing influence. The French government's July 2019 defense strategy for the Indo-Pacific identifies the following strategic dynamics characterizing the current geopolitical landscape in the region:

- The Structuring effect of the China-U.S. competition, which causes new alignments and indirect consequences;

- The decline of multilateralism, which results from diverging interests, challenge to its principles and promotion of alternative frameworks;

- The shrinking of the geostrategic space and the spillover effects of local crises to the whole region.97

In response to these dynamics, the French government aims to reaffirm its strategic autonomy, the importance of its alliances, and its commitment to multilateralism. The government's stated strategic priorities in the region are:

- Defend and ensure the integrity of [France's] sovereignty, the protection of [French] nationals, territories and EEZ;

- Contribute to the security of regional environments through military and security cooperation;

- Maintain free and open access to the commons, in cooperation with partners, in a context of global strategic competition and challenging military environments;

- Assist in maintaining strategic stability and balances through a comprehensive and multilateral action.98

India

France and India expanded their strategic partnership during Macron's March 2018 visit to India. India and France have agreed to hold biannual summits, signed an Agreement Regarding the Provision of Reciprocal Logistics Support, and "agreed to deepen and strengthen the bilateral ties based on shared principles and values of democracy, freedom, rule of law and respect for human rights." Among other agreements, the two governments issued a Joint Strategic Vision of India-France Cooperation in the Indian Ocean Region which states, "France and India have shared concerns with regard to the emerging challenges in the Indian Ocean Region." India signed a deal with France to purchase 36 Dassault Rafale multi-role fighter aircraft in 2016 for an estimated $8.7 billion. France and India also hold the annual Varuna naval exercise.

Australia

France is also developing its bilateral strategic and defense relationships with Australia, Japan, and Vietnam. While visiting Australia in May 2018, Macron stated that he wanted to create a "strong Indo-Pacific axis to build on our economic interests as well as our security interests." Several agreements were signed during Macron's visit to Australia, and Australia and France agreed to work together on cyberterrorism and defense. French company DCNS was previously awarded an estimated $36.3 billion contract to build 12 submarines for Australia. Australia and France held their inaugural Defense Ministers meeting in September 2018.

Other

French President Macron and Japanese Prime Minister Abe agreed to increase their cooperation to promote stability in the Indo-Pacific during Abe's visit to France in October 2018. France and its former colony Vietnam signed a Defense Cooperation Pact in 2009, and upgraded relations to a Strategic Partnership in 2013. A detachment of French aircraft visited Vietnam in August 2018 after taking part in exercise Pitch Black in Australia.

The United Kingdom

The UK also appears to be shifting its external focus to place relatively more emphasis on the Indo-Pacific. The UK's pending withdrawal from the European Union ("Brexit") may drive it to seek expanded trade relations in the Indo-Pacific region. Speaking to the Shangri La Dialogue in Singapore in 2018, then-UK Secretary of State for Defence Gavin Williamson stated:

Standing united with allies is the most effective way to counter the intensifying threats we face from countries that don't respect international rules. Together with our friends and partners we will work on a more strategic and multinational approach to the Indian Ocean region—focusing on security, stability and environmental sustainability to protect our shared prosperity.99

In 2018, three Royal Navy ships were deployed to the Indo-Pacific region and in April 2018, the UK opened a new naval support facility in Bahrain that will likely be capable of supporting the new aircraft carriers HMS Queen Elizabeth and HMS Prince of Wales. It is reported that HMS Queen Elizabeth could be deployed to the Pacific soon after entering active service in 2020.100 In August 2018, the HMS Albion sailed near the disputed Paracel Islands—waters that China considers its territorial seas but which are also claimed by others in a sovereignty dispute.101 A Royal Navy spokesman stated that "HMS Albion exercised her rights for freedom of navigation in full compliance with international law and norms."102 China strongly protested the operation, describing it as a provocation.

Emerging Strategic Partnerships

The UK has Commonwealth ties to numerous states across the Indo-Pacific littoral. UK forces participate in annual exercises of the Five Power Defence Arrangement (FPDA), a regional security group of Australia, Malaysia, New Zealand, Singapore, and the UK that was established in 1971. The UK also has a battalion of Gurkha infantry based in Brunei. The UK opened new High Commissions in Vanuatu, Tonga, and Samoa in 2019, and signed a new Defence Cooperation Memorandum of Understanding with Singapore on the sideline of the 2018 Shangri-La Dialogue. In December 2018, then-Defence Secretary Gavin Williamson generated headlines with an interview in which he stated the UK would seek new military bases in Southeast Asia; observers speculated that Brunei and Singapore would be the most likely locations.103 In 2013, Australia and the UK signed a new Defence and Security Cooperation Treaty that provides an enhanced framework for bilateral defense cooperation. The treaty builds on longstanding defense cooperation through the FPDA and intelligence cooperation through the Five Eyes group that also includes Canada, New Zealand, and the United States. Australia has also signed an agreement with UK defense contractor BAE Systems to purchase nine new Type 26 frigates in a deal worth an estimated $25 billion.104

In August 2017, the UK and Japan agreed on a Joint Declaration on Security Cooperation pledging to enhance the two countries' global security partnership.105 The two nations also hold regular Foreign and Defense Ministerial Meetings. Then-British Foreign Secretary Jeremy Hunt met with Japanese Foreign Minister Taro Kono in Tokyo in September 2018 and Kono welcomed the further presence of the UK in the Indo-Pacific region. In September 2018, the HMS Argyll and Japan's largest warship, the Kaga helicopter carrier, held exercises in the Indian Ocean and in October 2018, the UK and Japan held a joint army exercise in central Japan.106

Alongside indications of the UK's increasing focus on the region, observers also note that resource constraints and competing priorities could limit the degree to which the UK reengages with the Indo-Pacific. Bilateral cooperation, such as the participation of UK forces in France's 2018 Jeanne d'Arc naval operation in the Asia-Pacific, could potentially develop into a platform whereby other European countries might become more engaged.107 At the same time, regional states may view a more engaged Europe as a potential alternative to the U.S. as they hedge against a rising China and feel uncertainty U.S. leadership in the region.

ASEAN and Member States

The 10 members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), Southeast Asia's primary multilateral grouping, see a range of challenges resulting from the region's evolving strategic dynamics.108 Many Southeast Asian observers are unsettled by the prospect of extended strategic and economic rivalry between the United States in China, and the effect it would have on stability and economic growth in the region.109 New formulations of an Indo-Pacific region have raised concern for some in ASEAN, as they could lead to new diplomatic and security architectures that may weaken ASEAN's role in regional discussions or may not include all ASEAN's members.

ASEAN as a grouping is constrained by its members' widely diverging views of their strategic and economic interests, and by the group's commitment to decision-making via consensus. However, ASEAN's individual members have responded to new regional dynamics in various ways. Many have expanded defense spending to deepen their own capabilities and hedge against uncertainties including those caused by China's rise. Some, particularly Indonesia, have rhetorically adopted Indo-Pacific visions of the region, but these have not markedly changed substantive strategic postures.

In July 2019, ASEAN's leaders agreed to a five-page statement called the ASEAN Outlook on the Indo-Pacific.110 Some observers noted that ASEAN's statement was likely driven by other "Indo-Pacific" plans from the United States, Japan, and India, and by the group's desire not to be sidelined in the development of new ideas of Asian regionalism.111

ASEAN has long seen itself at the center of Asia's multilateral diplomacy—a concept the group's members refer to as "ASEAN centrality." Founded in part as a forum for dialogue that would prevent intra-regional conflict and help protect member states from great power influence, it has not traditionally taken a major security role, but rather has seen itself as a diplomatic hub that convenes other powers to discuss security and economic issues. Over the past few decades, East Asia's regional institutions have almost all centered around ASEAN as a "neutral" convening power.

U.S. Administration officials have sought to reassure ASEAN of its continued importance in the Indo-Pacific formulation. "ASEAN is literally at the center of the Indo-Pacific," Secretary of State Mike Pompeo said in July 2018, "and it plays a central role in the Indo-Pacific vision that America is presenting."112

The Indo-Pacific Outlook statement sought to define a role for ASEAN in shaping Indo-Pacific diplomatic, security, and economic arrangements. It welcomed the linkage of the Asia-Pacific and Indian Ocean regions, and stated that "it is in the interest of ASEAN to lead the shaping of their economic and security architecture…. This outlook is not aimed at creating new mechanisms or replacing existing ones; rather it is an outlook intended to enhance ASEAN's community building process and to strengthen and give new momentum for existing ASEAN-led mechanisms." The statement did envision a role for ASEAN to "develop, where appropriate, cooperation with other regional and sub-regional mechanisms in the Asia-Pacific and Indian Ocean regions on specific areas of common interests."

The statement listed four areas of cooperation for the nations of the Indo-Pacific: maritime cooperation; efforts to improve connectivity; efforts to meet the 2030 U.N. Agenda for Sustainable Development; and economic cooperation in areas such as trade facilitation, the digital economy, small and medium sized enterprises, and addressing climate change and disaster risk reduction and management.

ASEAN convenes and administratively supports a number of regional forums that include other governments, including the United States, such as the 27-member ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF), the 16 member East Asia Summit (EAS), numerous "ASEAN+1" dialogues between the group and its partners, as well as several other multilateral groupings. While many of the region's pressing security challenges, such as North Korea's nuclear proliferation, China-Taiwan tensions, or India-Pakistan rivalries, do not directly involve ASEAN's members, they argue that their ability to convene other powers in diplomacy is a core ASEAN role.

That said, ASEAN has moved into a more active security role in recent years. The ASEAN Defense Ministers Meeting-Plus (ADMM+) is a regional security forum that includes ASEAN's 10 members and the eight ASEAN partners—the United States, China, Japan, South Korea, Australia, New Zealand, India, and Russia. With U.S. backing, it has become more active in recent years, hosting multilateral dialogues and exercises in areas such as humanitarian assistance/disaster relief and maritime rescue. In 2018, ASEAN conducted a multilateral naval exercise with China, and in September 2019, it did so with the United States—moves that analysts called a strong signal of the group's desire to avoid working too closely to one military or the other.113

ASEAN's members have long sought to navigate changes in the regional security environment in ways that protect their own individual and collective interests, while avoiding being either dominated by external powers or drawn into external conflicts. In recent years, many observers believe China has sought to drive wedges between ASEAN's members based on their diverse interests—particularly the extensive investment by Chinese firms in smaller countries such as Cambodia and Laos—and has had some success due to the group's insistence in governing by consensus. Since 2013, ASEAN has been engaged in negotiations with China to develop a Code of Conduct for parties in the South China Sea, but it has generally rejected suggestions such as Beijing's proposal that parties pledge not to conduct military exercises with "outside" countries.

Indonesia

Indonesia is a strong proponent of Indo-Pacific conceptions of the region, considering itself to be at the geographic midpoint linking the Pacific and Indian Ocean regions. Most observers saw the ASEAN Outlook on the Indo-Pacific statement as an initiative driven most strongly by Indonesia.114 However, Indonesia's role as a founder and leader of the Non-Aligned Movement continues to shape its foreign policy, and Jakarta has been hestitant to deepen security partnerships too far with either the United States or China. That reluctance makes Indonesia a relatively passive actor in the broad Indo-Pacific security architecture.

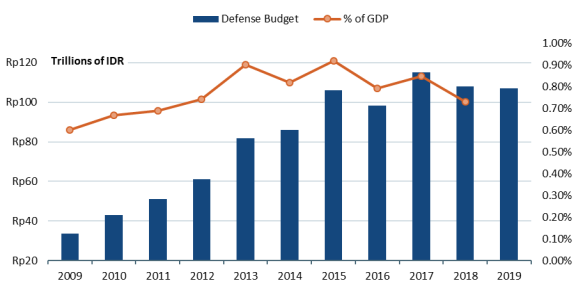

U.S.-Indonesia security cooperation has deepened over the past decade as the Indonesian government sought to expand the country's external defense capabilities, with the two militaries conducting more than 240 military engagements annually, including efforts to intensify maritime security cooperation and combat terrorism.115 In 2015, President Joko Widodo's government announced plans to increase military spending to 1.5% of GDP from recent levels below 1%,116 focusing particularly on maritime capabilities, although spending has not increased at such a pace. Indonesia, however, is increasingly involved in rising South China Sea tensions.

Indonesia has long had a delicate relationship with China, marked by deep economic interdependence (China is a major consumer of Indonesian natural resources) but considerable strategic mistrust. Periodic violence directed at the Indonesian-Chinese community throughout Indonesian history casts further complications on Jakarta-Beijing relations.117 A 2018 Pew survey found that 53% of Indonesians had a positive view of China, down from 66% in 2014 and 73% in 2005.118 (The same poll, conducted in spring 2018, found that 42% of respondents had a positive view of the United States, a number that has dropped from 63% in 2009, and also that 22% of Indonesians believe it would be better for the world if China was the world's leading power, while 43% said it would be better if the United States occupied that role.)

Singapore

Singapore is one of the United States' closest security partners in Southeast Asia. Its security posture is guided by its desire to serve as a useful balancer and intermediary between major powers in the region, and its efforts to avoid and hedge against anything that would force it to "choose" between the United States and China.

In recent years Singapore has been an enthusiastic participant in new defense partnerships, but it has also been relatively skeptical, at least rhetorically, of the Trump Administration's Free and Open Indo-Pacific concept. While it has urged continued U.S. engagement in Asia, it has also been careful to warn that anti-China rhetoric or efforts to "contain" China's rise would be counterproductive. In a May 2019 speech in Washington DC, Singapore Foreign Minister Vivian Balakrishnan said "viewing China purely as an adversary to be contained will not work in the long term, given the entire spectrum of issues that will require cooperation between the U.S. and China."119

In 2019, Singapore was reportedly the last nation to agree to ASEAN's Indo-Pacific Outlook statement, viewing it as an unproductive move that did not address broader security issues but which would inevitably raise tensions with China, and prospectively the United States.120 In questions about Singapore's view of the Trump Administration's FOIP concept, Singapore Foreign Minister Vivian Balakrishnan said in May 2018: "Frankly right now, the so-called free and open Indo-Pacific has not yet fleshed out sufficient level of resolution to answer these questions that I've posed.... We never sign on to anything unless we know exactly what it means."121

That said, Singapore has worked to develop new security arrangements. Singapore maintains a close security partnership with Australia: The two nations signed an agreement in 2016 under which Singapore would fund an expansion of military training facilities in Australia and would gain expanded training access in Australia, as well as enhanced intelligence sharing in areas such as counter-terrorism. In September 2019, Singapore held the first trilateral naval exercise with India and Thailand in the Andaman Sea, and agreed in November 2019 to make this an annual exercise. Singapore is also negotiating with India on an agreement that could allow the Singapore armed forces to use Indian facilities for live-fire drills—an important consideration for Singapore, given its small size.122

Singapore retains strong security ties with the United States, formalized in the 2005 "Strategic Framework Agreement." The agreement builds on the U.S. strategy of "places-not-bases"—a concept that aims to provide the U.S. military with access to foreign facilities on a largely rotational basis, thereby avoiding sensitive sovereignty issues. The agreement allows the United States to operate resupply vessels from Singapore and to use a naval base, a ship repair facility, and an airfield on the island-state. The U.S. Navy also maintains a logistical command unit—Commander, Logistics Group Western Pacific—in Singapore that serves to coordinate warship deployment and logistics in the region.

Singapore is a substantial market for U.S. military goods, and the United States has authorized the export of over $37.6 billion in defense articles to Singapore since 2014. In particular Singapore has purchased aircraft, parts and components, and military electronics, and has indicated interest in procuring four F-35 jets. Over 1,000 Singapore military personnel are assigned to U.S. military bases, where they participate in training, exercises, and professional military education. Singapore has operated advanced fighter jet detachments for training in the continental United States for the past 26 years.123

Singapore adheres to a one-China policy, but has an extensive relationship with Taiwan, including a security agreement under which Singapore troops train in Taiwan—an agreement that Beijing has occasionally asked it to terminate.124 Generally, Singapore has managed to avoid damaging its strong relations with Beijing. Of late, Singapore has worked to smooth its ties with China—perhaps at least partly as a hedge against possible U.S. disengagement from the region. That being said, Singapore has judiciously pushed back against Chinese behavior it sees as problematic; in 2016, Singapore supported an international tribunal's ruling against China's assertions of sovereignty over extensive waters in the South China Sea.

Vietnam

Since the establishment of diplomatic relations between the United States and the Socialist Republic of Vietnam in 1995, the two countries' often overlapping strategic and economic interests have led them to incrementally expand relations across a wide spectrum of issues. For the first decade and a half of this period, cooperation between the two countries' militaries was embryonic, largely due to Vietnam's reluctance to advance relations more rapidly. By the late 2000s, however, China's actions in the South China Sea appear to have caused the Vietnamese government to take a number of steps to increase their freedom of action. First, Vietnam began trying to increase its defense capabilities, particularly in the maritime sphere. In the words of two analysts, these efforts "for the first time" have given Vietnam "the ability to project power and defend maritime interests."125 From 2009 to 2019, Vietnam increased its military budget by over 80% in dollar terms, to around $5.3 billion. In 2009, Vietnam signed contracts to purchase billions of dollars of new military equipment from Russia, its main weapons supplier, including six Kilo-class submarines. It has also begun engaging in more maritime military diplomacy with its neighbors, and for the first time has begun dispatching peacekeepers to United Nations missions.126

Second, as Vietnamese leaders perceived the strategic environment as continuing to deteriorate against them during the current decade, they deepened their cooperation with potential balancers such as the United States, Japan, and India. With the United States, Vietnam is one of the recipient countries in the Defense Department's $425 million, five-year Southeast Asia Maritime Security Initiative, first authorized in the FY2016 National Defense Authorization Act (P.L. 114-92). In December 2013, the United States announced it would provide Vietnam with $18 million in military assistance, including new coast guard patrol boats, to enhance Vietnam's maritime security capacity, assistance that the Trump Administration has expanded. The United States also has transferred to Vietnam a decommissioned U.S. Coast Guard Hamilton-class cutter, under the Excess Defense Articles program. The cutter is Vietnam's largest coast guard ship. The United States in recent years also has provided Vietnam with Scan Eagle Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) and T-6 trainer aircraft. In a largely symbolic move, in March 2018, the USS Carl Vinson conducted a four-day visit to Da Nang, the first U.S. aircraft carrier to visit Vietnam since the Vietnam War.

Vietnam's willingness to openly cooperate with the United States' Indo-Pacific strategy is limited by a number of factors, however. Since the late 1980s, Vietnam's leaders explicitly have pursued what they describe as an "omnidirectional" foreign policy by cultivating as many ties with other countries as possible, without becoming overly dependent on any one country or group of countries. Some have referred to this approach as a "clumping bamboo" strategy, behaving like bamboo that will easily fall when standing alone but will remain standing strong when growing in clumps.127 In practice, this has meant Vietnam often pairs its outreach to the United States and other powers like Japan and India with similar initiatives with China. Despite increased rivalry with Beijing, Vietnam regards its relationship with China as its most important bilateral relationship, and Hanoi usually does not undertake large-scale diplomatic or military moves without first calculating Beijing's likely reaction. The two countries have Communist Party-led political systems, providing a party-to-party channel for conducting relations, and contributing to often similar official world-views. China also is Vietnam's largest bilateral trading partner.

One corollary to Vietnam's omnidirectional approach is its official "Three Nos" defense policy: no military alliances, no aligning with one country against another, and no foreign military bases on Vietnamese soil to carry out activities against other countries. This approach, which barring a major shock likely will continue into the medium term, is likely to limit Vietnam's willingness to explicitly become a full partner in many of the elements of the Trump Administration's Indo-Pacific strategy, particularly if they are presented as explicitly aimed against China.

That said, Vietnam has demonstrated in the past that it is willing to stretch the limits of its "Three Nos" policy. This has been particularly true in areas of defense cooperation such as military training and arms sales that can be undertaken quietly and/or portrayed as not aimed at one specific country. Many Vietnam watchers therefore expect that in the absence of a major shock—such as a U.S.-Vietnam trade war or open Sino-Vietnam military conflict—Vietnam will continue its approach of quietly and incrementally expanding its cooperation with the United States and its partners.128

Questions for Congress

Based on the above, it appears that a key development in the strategic landscape of the Indo-Pacific is that U.S. allies and partners are developing closer strategic relations across the region as a way of hedging against the rise of China and the potential that the United States will either be less willing or less able to be strategically engaged. Given this, a key question for Congress is how the United States should respond to this emerging dynamic. Do these emerging intra-Asian strategic relationships support U.S. strategic objectives across the Indo-Pacific and if so, to what extent, and in what ways, should to the United States support them?

Some analysts question whether the Trump Administration's skepticism of allies is affecting, or may affect, U.S. ability to work with Japan, South Korea, and Australia in developing new security arrangements. In particular, Trump Administration requests for large increases in allies' monetary contributions to basing cost has raised significant concerns about what future alliance arrangements may look like. Similarly, some question whether the Administration's lack of interest in multilateral trade agreements such as the TPP may affect perceptions of regional allies and partners about broader U.S. commitment to the region. These raise questions Congress may consider, including: What are the United States' key interests in the region and have they changed over time? What role does cooperation with U.S. allies play in ensuring U.S. interests are promoted as the region's new security architecture develops? What is the proper mix of diplomatic, economic, defense, foreign assistance, and soft power that should be used in such an effort?

Some political developments in the region may also play a role in how Congress addresses these questions. In the Philippines and Thailand, both U.S. treaty allies, political developments have led to what many observers describe as a decline in democratic institutions. In India, a partner and important participant in Indo-Pacific arrangements, many are concerned about increasing intolerance and human rights abused against religious minorities. These developments raise questions such as: What role should Congress play in helping the Trump Administration, and future administrations, articulate U.S. strategy to the region and to what extent should American values, as well as U.S. interests, inform such an approach?

Congress has consistently played an important role in guiding and helping set U.S. policy in Asia. As noted above, the Asia Reassurance Initiative Act of 2018 (ARIA; P.L. 115-409), states: "Without strong leadership from the United States, the international system, fundamentally rooted in the rule of law, may wither.... It is imperative that the United States continue to play a leading role in the Indo-Pacific." Congress may assess how growing military spending and new security arrangements affect that goal.