Surprise Billing

As the term is currently being discussed, surprise billing typically refers to situations where a consumer is unknowingly, and potentially unavoidably, treated by a provider outside of the consumer's health insurance plan network and, as a result, unexpectedly receives a larger bill than he or she would have received if the provider had been in the plan network.1

Most recently, in federal policy discussions, surprise billing has commonly been discussed in the context of two situations: (1) where an individual receives emergency services from an out-of-network provider and (2) where a consumer receives nonemergency services from an out-of-network provider who is working in an in-network facility. However, surprise billing may occur in other situations (e.g., ground ambulance and air ambulance services) where consumers are unknowingly and unavoidably treated by an out-of-network provider.

As these situations imply, surprise billing is rooted in most private insurers' use of provider networks. Therefore, this report begins with a discussion of the relationship between provider network status and private health insurance billing before discussing existing federal and state requirements around surprise billing.

This report then discusses various policy issues that Congress may want to consider when assessing surprise billing proposals. Such policy topics include what plan types should be addressed; what types of services or provider types should be addressed; what types of consumer protections should be established; what requirements (including financial requirements) should be placed on insurers, providers, or both; how these policies will be enforced; and what is the role of the state. The list of topics discussed in this report is not exhaustive but should touch on many aspects of the surprise billing proposals currently under consideration.

The report also briefly discusses potential impacts of the various surprise billing approaches. It then concludes with an Appendix table comparing two federal proposals that have gone through committee markup procedures. Specifically, the proposals included in the appendix are Title I of S. 1895 (Alexander), which went through a Senate Committee Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions (HELP) markup session on June 26, 2019, and Title IV of the amendment in the nature of a substitute (ANS) to H.R. 2328, which went through a markup session held by the House Committee on Energy and Commerce on July 17, 2019. As of the date of this report, no other proposals have been approved through committee markup or gone further in the legislative-making process.

Private Health Insurance Billing Overview

The charges and payments for health care items or services under private health insurance are often the result of the contractual relationships between consumers, insurers, and providers for a given health plan.

Health care providers establish dollar amounts for the services they furnish; such amounts are referred to as charges and reflect what providers think they should be paid. However, the actual amounts that a provider is paid for furnishing services vary and may not be equal to the provider-established charges. The amounts a provider receives for furnished services, and how the payment is divided between the insurer and the consumer, can vary due to a number of factors, including (but not limited to) whether a given provider has negotiated a payment amount with a given insurer, whether an insurer pays for services provided by out-of-network providers, enrollee cost-sharing requirements, whether a provider can bill the consumer for an additional amount above the amounts paid by the consumer (in the form of cost sharing), and the insurer.

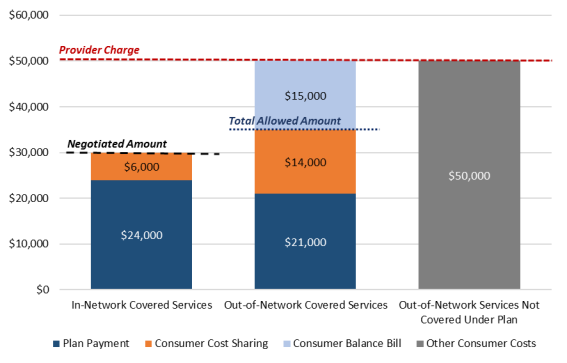

Figure 1 highlights the effects of the aforementioned distinctions. The following sections discuss them in the context of in-network and out-of-network billing.

In-Network Coverage

Under private insurance, the amount paid for a covered item or service is often contingent upon whether a consumer's insurer has contracted with the provider. Insurers typically negotiate and establish separate contracts with hospitals, physicians, physician organizations (such as group practices and physician management firms), and other types of providers.2 For each provider where such a contract exists with a particular insurer, that provider is then generally considered to be a part of that insurer's provider network (i.e., that provider is considered in network).

The contents of contracts between insurers and providers vary and typically are the result of negotiations between providers and insurers; however, these contracts generally specify the amounts that providers are to receive for providing in-network services to consumers (i.e., negotiated amounts).3 Negotiated amounts typically are lower than what providers would otherwise charge, had they not contracted with an insurer.

When an in-network provider furnishes a service to a consumer, the insurer and consumer typically will share the responsibility of paying the provider the negotiated amount established in the contract.4 The consumer's portion of the negotiated amount is determined in accordance with the cost-sharing requirements of the consumer's health plan (e.g., deductibles, co-payments, coinsurance, and out-of-pocket limits; see Figure 1).5 Consumers who receive covered services from in-network providers generally have lower cost-sharing requirements than consumers who receive the same services out of network.

Generally, in-network providers are contractually prohibited from billing consumers for any additional amounts above the negotiated amount (i.e., balance bill).

Out-Of-Network Coverage

In instances where a contract between an insurer and provider does not exist, the provider is considered out of network. The total costs for services furnished by an out-of-network provider, and who pays for such services, depend on a number of factors; one key factor is whether the plan covers out-of-network services in the first place.

Generally, point of service plans and preferred provider organization (PPO) plans cover out-of-network services, whereas exclusive provider organization plans and health maintenance organization (HMO) plans generally only cover services by providers within the plan's network (except in an emergency).6

Insurer Pays for Out-Of-Network Services

In instances where an insurer pays some amount toward out-of-network services, both the consumer and the insurer contribute some amount to the provider, with the consumer's amount determined in accordance with the plan's cost-sharing requirements. Consumer cost-sharing requirements for services provided by an out-of-network provider may be separate from (and are typically larger than) cost-sharing requirements for the same services provided by an in-network provider. For example, a plan may have different deductibles for in-network and out-of-network services.

Table 1 provides an example of how cost-sharing requirements may differ for in-network and out-of-network services.

|

Selected Cost-Sharing Requirements |

In-Network |

Out-of-Network |

|

Deductible |

$350 overall deductible |

|

|

Coinsurance Rate (Outpatient Surgery) |

15% of negotiated amount |

35% of total allowed amount |

|

Out-of-Pocket Limit |

$7,000 |

No limit |

Source: Congressional Research Service (CRS) illustrative example.

Although cost-sharing requirements will indicate how the cost for the service is shared between an insurer and a consumer, the insurer needs to determine the total amount that cost-sharing requirements will be based on (since there are no negotiated amounts established in contracts between out-of-network providers and insurers). The amount ultimately determined by the insurer is often referred to as the total allowed amount and does not necessarily match the negotiated amount insurers may have contracted with other providers or the provider charge amount for that service. If a total allowed amount is larger than a negotiated rate, then the consumer's payment for out-of-network services could be larger than a corresponding payment for in-network services because of increased cost sharing, as per the terms of the plan and the fact that the total cost of services on which consumer cost sharing is based is larger.

Insurers have their own methodologies for calculating the total allowed amount. They may do so by incorporating the usual, customary, and reasonable rate (UCR), which is the amount paid for services in a geographic area based on what providers in the area usually charge for the same or similar medical services.7

If an out-of-network provider's total charge for a service exceeds the total allowed amount (and if allowed under state law), the provider may directly bill (i.e., balance bill) a consumer for the amount of that difference (sometimes referred to as the excess charge; see Figure 1). The consumer would therefore be responsible for paying amounts associated with any cost-sharing requirements and the balance bill.

The provider is responsible for collecting any balance bill amounts; from an administrative standpoint, it is considered more difficult to collect these balance bill amounts than to collect payments from insurers.8 In some instances, providers may ultimately settle with balance-billed consumers for amounts that are less than the total balance bill.

There are no federal restrictions on providers balance billing consumers with private health coverage.

Insurer Does Not Pay for Out-of-Network Services

If the insurer pays only for in-network services, the consumer is responsible for paying the entire bill for out-of-network services (represented in Figure 1 as "Out-of-Network Services Not Covered Under Plan").9 Although the consumer pays the provider in this instance, the consumer costs are not technically cost sharing (since the insurer is not sharing costs with the consumer), nor are they the balance remaining after the provider receives certain payments. Therefore, this report refers to these costs as other consumer costs.10

Similar to balance bills, providers are responsible for collecting these other consumer costs and ultimately may decide to settle with the consumer for amounts that are less than the initial provider charges.

Existing Requirements Addressing Surprise Billing

Federal Requirements

Currently, no federal private health insurance requirements address surprise billing; however, federal requirements do address related issues. The Affordable Care Act (ACA; P.L. 111-148, as amended) established requirements regarding consumer cost sharing for, and plan coverage of, out-of-network emergency services and consumer cost-sharing requirements for ancillary provider services furnished at in-network facilities.

Emergency Services

As a result of the ACA, if a self-insured plan or a fully insured large-group plan, small-group plan, or individual-market plan covers services in a hospital emergency department, the plan is required to cover emergency services irrespective of the provider's contractual status with the plan.11 In other words, insurers of plans that cover in-network emergency services are effectively required under the ACA to contribute some amount to a provider that furnishes out-of-network emergency services to an enrolled consumer, even if the insurer otherwise would not contribute any amount for services furnished by other types of out-of-network providers.

More specifically, insurers are required to recognize the greatest of the following three payment standards as the total allowed amount for emergency services: (1) the median amount the insurer has negotiated with in-network providers for the furnished service;12 (2) the usual, customary, and reasonable amount the insurer pays out-of-network providers for the furnished service; or (3) the amount that would be paid under Medicare for the furnished service.13 (Insurers may recognize another amount as the total allowed amount provided such amount is larger than all three of the aforementioned amounts.) After determining the appropriate total allowed amount, the insurer and the consumer each will pay the provider a portion of the total allowed amount, according to the cost-sharing requirements of the consumer's plan.

The ACA requirement also addressed a consumer's payment responsibility vis-à-vis her health plan for out-of-network emergency care. Specifically, when a consumer receives emergency services from an out-of-network provider, the ACA limits a consumer's cost sharing, expressed as co-payment amount or coinsurance rate, to the in-network amount or rate of the consumer's health plan.14 In other words, if a consumer receives out-of-network emergency services and is enrolled in a plan that has a 15% coinsurance rate for in-network services and a 30% coinsurance rate for out-of-network services, the consumer will be responsible for 15% of the total allowed amount for the out-of-network care.15

The requirement does not address the plan deductible or out-of-pocket limits. Therefore, if a plan has separate deductibles and out-of-pocket limits for in-network and out-of-network services, then the plan may require that consumer payments for out-of-network emergency services be applied to these out-of-network amounts. As a result, although a consumer would be subject to in-network co-payment amounts or coinsurance rates, the consumer may still be responsible for greater cost sharing than if the payments for the services were applied to the in-network deductible and out-of-pocket limit.

The requirement does not limit a provider from balance billing the consumer after receiving consumer cost-sharing and insurer payment amounts.

Ancillary Provider Services

Individual-market and small-group plans must adhere to network adequacy standards in order to be sold on an exchange. As part of these standards, plans with provider networks must count consumer cost sharing for an essential health benefit furnished by an out-of-network ancillary provider at an in-network facility toward the consumer's in-network out-of-pocket maximum, unless the plan provides a notice to the consumer prior to the furnishing of such services.16

State Requirements

Although there are no federal requirements that directly address surprise billing, at least half of states have implemented policies to address some form of surprise billing. As of July 2019, 26 states had addressed surprise billing for emergency department services and 19 states had addressed surprise billing for nonemergency care at in-network hospitals.17 State policies to address surprise bill vary and, as a result, have created different sets of requirements on insurers and providers to establish different sets of protections for consumers. However, state surprise billing laws are consistent in that they do not apply requirements to self-insured plans (see text box below).

|

Federal and State Regulation of Insurance States are the primary regulators of the business of health insurance, as codified by the 1945 McCarran-Ferguson Act. Each state requires insurers to be licensed in order to sell health plans in the state, and each state has a unique set of requirements that apply to state-licensed issuers and the plans they offer. State oversight of health plans applies only to plans offered by state-licensed issuers. Because self-insured plans are financed directly by the plan sponsor, such plans are not subject to state law. The federal government also regulates state-licensed insurers and the plans they offer. Federal health insurance requirements typically follow the model of federalism: federal law establishes standards, and states are primarily responsible for monitoring compliance with, and enforcement of, those standards. Generally, the federal standards establish a minimum level of requirements (federal floor) and states may impose additional requirements on insurers and the plans they offer, provided the state requirements neither conflict with federal law nor prevent the implementation of federal requirements. The federal government also regulates self-insured plans, as part of federal oversight of employment-based benefits. Federal requirements applicable to self-insured plans often are established in tandem with requirements on fully insured plans and state-licensed issuers. Nonetheless, fewer federal requirements overall apply to self-insured plans compared with fully insured plans. Note: For an overview of the regulation of private health plans, see "Regulation of Private Health Plans" in CRS Report R45146, Federal Requirements on Private Health Insurance Plans. |

Multiple research organizations have highlighted the differences among state policies. They have shown whether state surprise billing policies (1) determine the amounts or methodologies by which providers are paid by insurers and consumers for specified out-of-network services; (2) include transparency standards for providers and insurers (e.g., notification requirements on providers or requirements on insurers with respect to provider directory maintenance), (3) address different types of provider settings and services, and (4) address different types of plans (i.e., HMO or PPO).18

The National Academy of State Health Policy (NASHP) examined the differences between the eight states with surprise billing laws. As an example of the variance between states, NASHP indicated that the eight states varied in terms of how the total allowable amount is set under the laws. Further, two states set payment standards based on a greater of multiple benchmark rates, one state sets payment standards based on a lesser of multiple benchmark rates, one state sets payment standards based on the commercially reasonable value, one state sets payment standards based on the rates set under a regulatory authority within the state, and four states create a dispute-resolution process to resolve surprise balance bills.19

In addition to the often-discussed out-of-network emergency services provided in facilities and services provided by out-of-network providers at in-network facilities, some states have attempted to regulate ground and air ambulance surprise billing, albeit to a lesser extent.20 Although states have attempted to regulate air ambulances, they have been limited in their ability to do so as a result of the Airline Deregulation Act of 1978 (P.L. 95-504), which preempts state regulation of payment rates for certain air transportation carriers (including air ambulances).21

Policy Considerations

Federal surprise billing proposals, like state laws, typically seek to address the current financial relationships between insurers, providers, and consumers for certain services. In doing so, the proposals generally would establish new requirements on insurers, providers, or both in specified billing situations to create a degree of consumer protection.

As an example, requirements on insurers may address how the insurer pays for specified services or what consumer cost-sharing requirements would be under specified plans. Requirements on providers may address the extent to which providers may balance bill consumers. Requirements on both entities may establish the terms under which insurers and providers participate in alternative dispute resolution processes (e.g., arbitration) to determine the amount providers are paid by insurers and consumers for surprise bills.

Surprise billing can be addressed in a variety of ways, and the following sections discuss questions policymakers may want to consider when evaluating these different approaches. The following policy discussions are examples of the types of questions policymakers may want to consider when evaluating surprise billing proposals and should not be treated as an exhaustive list.

Furthermore, due to the development, introduction, and modification of numerous federal proposals on this topic during the 116th Congress, the policy discussions in this section of the report generally do not include specific references to any current or historical federal proposals. The report references state surprise billing laws to provide examples and context, but such references should not be considered comprehensive references of all applicable state laws.

Although specific federal policies are not explicitly discussed in this section of the report, the report concludes with an Appendix that provides side-by-side summaries of the two surprise billing proposals from the 116th Congress that have passed through committee markups, both as part of larger bills. Specifically, the proposals included in the appendix are Title I of S. 1895 (Alexander), which went through a Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions (HELP) markup session on June 26, 2019, and Title IV of the amendment in the nature of a substitute (ANS) to H.R. 2328, which went through a markup session held by the House Committee on Energy and Commerce on July 17, 2019.22

What Plan Types Could Be Addressed?

Federal private health insurance requirements generally vary based on the segment of the private health insurance market in which the plan is sold (individual, small group, large group, and self-insured).23 Some requirements apply to all market segments, whereas others apply only to selected market segments.24 For example, plans offered in the individual and small-group markets must comply with the federal requirement to cover the essential health benefits; however, plans offered in the large-group market and self-insured plans do not have to comply with this requirement.

States, in their capacity as the primary regulators of health insurance plans, can regulate fully insured plans in the individual, small-group, and large-group markets. States are not able to directly apply surprise billing requirements to self-insured plans, but certain state requirements may affect state residents enrolled in a self-insured plan. For example, at least one state (New Jersey) has allowed self-insuring entities to opt in to surprise billing requirements.25

Relatedly, state requirements on providers may affect consumers with self-insured coverage. For example, New York established an arbitration process for certain surprise billing situations, which applied to providers and fully insured plans. This arbitration process did not apply to self-insured plans. However, results from a National Bureau of Economic Research working paper suggest the policy affected consumers with both fully insured and self-insured plans. The authors hypothesized that because most providers were unaware of whether the consumer's plan was fully insured or self-insured, providers billed amounts that were "likely chosen to reflect the possibility of arbitration."26

In light of this example, to the extent that a federal proposal would establish requirements on providers for consumers enrolled in plans in a specific market segment (e.g., only self-insured plans), providers may need to develop processes to determine whether a consumer has such a plan, as this information is not necessarily available to the provider when services are furnished. Broadly applying a provider requirement so that it addresses consumers enrolled in all types of health plans would minimize the potential that consumers inadvertently receive a surprise bill. Many federal proposals would be broadly applicable to self-insured and fully insured individual, small-group, and large-group private health insurance plans, though there has been some variance with respect to certain types of plans (e.g., Federal Employees Health Benefits [FEHB] Program plans).27

What Types of Services or Provider Types Could Be Addressed?

Federal surprise billing proposals from the 116th Congress have commonly focused on variants of two different types of services: (1) where an individual receives emergency services from an out-of-network provider and (2) where an individual receives services from an out-of-network provider that is working at an in-network facility.

For context on the prevalence of surprise billing, a recent study estimated that 20% of hospital inpatient admissions from an emergency department, 14% of outpatient visits to an emergency department, and 9% of elective inpatient admissions in 2014 were likely to produce surprise medical bills (i.e., were "cases in which one or more providers were out of network and the patient was likely to be unaware of the provider's status or unable to choose an in-network provider for care instead").28 Another study found that the prevalence of similarly defined "surprise" out-of-network billing increased for emergency department visits and inpatient admissions between 2010 and 2016.29

Researchers have suggested that surprise billing tends to occur around these particular types of services due to a unique set of market forces that differentiate these services from how other services function within the provider-insurer-consumer relationship.30

Many providers decide to join an insurer's network (thereby accepting a lower negotiated rate for services) knowing that by doing so, the insurer will steer their enrollees toward in-network providers.31 Insurers steer their enrollees toward in-network providers by limiting plan coverage to in-network providers only or providing more generous coverage for in-network providers as compared with other out-of-network providers (i.e., reduced cost sharing). This approach effectively disincentives consumers from seeking out-of-network care in most situations.

However, in the aforementioned billing situations, consumers are not necessarily able to choose an in-network provider. For example, a consumer may be unconscious due to a medical emergency and unable to decide whether he or she wants to be seen by an in-network or out-of-network emergency provider. In this instance, the consumer may be taken to the nearest hospital emergency department (without consideration of network status of the hospital and/or the emergency department providers within the hospital). As another example, consumers may be able to select or seek out a particular in-network hospital or in-network surgeon for a specific procedure, but the consumers are unlikely to be able to select every provider participating in that specific procedure. This is especially true if the consumer is unaware of the need for additional assistance when he or she arranges the procedure.

Considering this, certain emergency and ancillary providers may have fewer incentives to join the network of a health insurer, since they are more likely to receive constant demand for their services regardless of network status and consumer choice. Instead, these provider types may find it more beneficial to stay out of network in order to be able to charge more for their services than the negotiated rate they would accept had they been considered in network.32

However, surprise billing is not limited to the aforementioned situations. It can occur in other situations (e.g., ambulance services or in situations where an in-network physician sends a consumer's lab test to an out-of-network lab).33

Some federal surprise billing proposals address air ambulance services, albeit fewer than address emergency services and services provided by out-of-network providers at in-network facilities. Air ambulances are similar to the previously discussed situations in that consumers often are not able to choose an in-network air ambulance due to the urgency associated with the request for services. In addition, the "relative rarity and high prices charged [by air ambulance providers] reduces the incentives of both air ambulance providers and insurers to enter into contracts with agreed-upon payment rates."34 For context, the Government Accountability Office found, as a result of its analysis of FAIR Health claims data, that 69% of air ambulance transports for privately insured consumers were out of network.35

In conclusion, surprise billing proposals may address one or multiple different types of situations. To the extent that the proposals address multiple situations, they may treat such situations similarly or may apply different types of requirements to each situation.

How Could a Proposal Address Consumer Protections?

In surprise billing situations, the consumer is typically the one being surprised. Correspondingly, proposals seeking to address surprise billing situations generally include provisions that would establish consumer protections.

Most federal surprise billing proposals from the 116th Congress generally address consumer financial liabilities in these situations. Generally, they do so by tying consumer cost sharing (in some capacity) to what cost sharing would be had specified services been provided in network and by limiting the extent to which consumers can be balance billed for specified services.

In addition, some federal proposals incorporate various requirements designed to inform consumers so they can make more informed choices about seeing in-network or out-of-network providers. In current federal proposals, this has most commonly taken the form of consumer notification requirements, which are designed to inform the consumer, prior to receiving out-of-network services, that he or she might be seen by an out-of-network provider (among other pieces of information). Some federal proposals link such notification requirements with consumer financial protections, so that the consumer financial protections would not apply in instances where notification requirements were satisfied (e.g., a consumer may be balanced billed only if the provider satisfied consumer notification requirements).

The aforementioned financial protections and notification requirements typically are established by creating requirements on insurers, providers, or both. They may take a variety of forms, as discussed in the subsequent sections.

What Could Be the Consumer's Financial Responsibility in Surprise Billing Situations?

As stated in the "Private Health Insurance Billing Overview" section, privately insured consumers may be liable for three types of consumer financial responsibilities when receiving services: cost sharing, balance bills, and other consumer costs. In out-of-network situations, consumers with plans that cover out-of-network benefits would potentially be responsible for consumer cost sharing and balance bills, whereas consumers with plans that do not cover out-of-network benefits would be responsible for other consumer costs.

Surprise billing requirements may address any combination of these three consumer financial responsibilities (cost sharing, balance billing, and other consumer costs), which would have direct implications on the total amount that consumers pay, and the total amount that providers receive as payment, for these services.36 Cost-sharing and balance billing requirements would affect those consumers with plans that cover services provided by out-of-network providers, whereas other consumer cost requirements would affect insured consumers with plans that do not cover services provided by out-of-network providers.37 The following sections discuss how surprise billing requirements associated with each of these financial responsibilities may be structured.

Cost Sharing

Consumer cost sharing for specified out-of-network services could be limited by defining, through requirements on plans, consumer cost-sharing rates for out-of-network services. Most federal proposals generally include cost-sharing requirements that tie cost sharing (in some capacity) to corresponding in-network requirements. One study of state-level surprise billing laws indicated that state-level laws generally included similar cost-sharing requirements.38 Although it has been common to tie out-of-network cost sharing to in-network requirements (e.g., the same co-payment amount or the same coinsurance percentage) for certain services, cost sharing could be tied to any rate or amount.

Cost-sharing requirements do not need to apply to deductibles, coinsurance rates, co-payment amounts, and out-of-pocket limits. For example, under current federal law, when a consumer receives emergency care from an out-of-network provider, the cost-sharing requirement, expressed as a co-payment or coinsurance rate, is limited to the in-network amount or rate of the consumer's health plan.39 Cost sharing does not address the plan deductible or out-of-pocket maximum. Therefore, under this requirement, insurers may apply out-of-network deductibles and out-of-pocket maximums for emergency services if such cost-sharing requirements generally apply to out-of-network benefits, which could increase the amount owed by the consumer as compared with a requirement that aligned the deductible, co-payment amount, coinsurance rate, and out-of-pocket limit.

Cost-sharing requirements do not necessarily specify the total dollar amount that a consumer pays for out-of-network services. For example, coinsurance is based on a percentage of the amount recognized by the insurer as the total cost of care.40 Therefore, the total cost-sharing dollar amount a consumer ultimately pays for care also may be influenced by any provisions that establish methodologies for determining the total cost of care for specified surprise billing situations.

Balance Billing

Establishing limitations on cost-sharing requirements alone does not prohibit or limit the extent to which a consumer may be balance billed (in instances where the plan covers out-of-network services).41 Therefore, if policymakers were interested in defining the extent to which a provider may balance bill a consumer (if at all), such language also would need to be included. Requirements that insulate consumers from balance billing may be placed on providers or insurers. For example, language may explicitly prohibit, fine, or limit the extent to which a provider can directly balance bill a consumer. By contrast, language may require insurers to "hold the consumer harmless" and pay the provider "their billed charges or some lower amount that is acceptable to the provider."42 From the consumer's perspective, both types of requirements would have similar effects, in that both requirements would result in the consumer only being responsible for paying the cost sharing associated with the service.

According to one study of state-level surprise billing laws, 28 states had incorporated provisions (as of July 31, 2019) that insulated consumers from certain balance bills through requirements on insurers, providers, or both.43

Other Consumer Costs

Surprise billing proposals may be structured so that consumers with a plan that does not cover out-of-network services (e.g., HMO) are treated differently in surprise billing situations than consumers with plans that do cover out-of-network services (e.g., PPO).44 For example, a surprise billing proposal may be structured so it applies only to consumers with plans that cover out-of-network benefits (i.e., it would not address other consumer cost situations).45 In other words, this type of policy could reduce a consumer's financial liabilities in surprise billing situations if the consumer were enrolled in a plan with out-of-network benefits, but it would not address the consumer's financial liabilities if the consumer were enrolled in a plan that does not cover out-of-network benefits.46

Alternatively, proposals may define the financial liability individuals face for receiving out-of-network care while enrolled in a plan that does not cover out-of-network benefits. Such requirements would effectively define the other consumer cost (i.e., the total cost of care) and could incorporate similar methodologies used in other surprise billing laws (e.g., benchmark). Without any additional requirements, the consumer would still be responsible for the entire other consumer cost.

Proposals also could include provisions that require insurers to cover a portion of the other consumer cost, effectively requiring the consumer's plan to cover that particular benefit.47 This could occur because of language that explicitly requires plans to cover a particular benefit or defines the amount that a plan must contribute for specified services.48

|

Excluded Services Although other consumer costs are generally referenced throughout this report in the context of network status, a consumer also may be in an other consumer cost situation if they receive a service that is not covered by the plan (i.e., receive an excluded service). Regardless of whether the consumer received the excluded service from an in-network provider, the consumer generally would be responsible for the full cost of care. Surprise billing proposals could apply protections only to covered services or could be applicable more broadly (e.g., to all specified services, without reference to whether the plan covers such services). |

To date, many federal surprise billing proposals have addressed other consumer costs by requiring insurers to cover a portion of such costs. Many federal proposals have done this by making surprise billing provisions that limit consumer costs in surprise billing situations to a specified amount (e.g., in-network cost sharing) and require insurers to contribute some amount to providers applicable to all plans, irrespective of whether a plan would cover such out-of-network service.

What Kind of Information Could Be Provided to the Consumer Prior to the Receipt of Services?

Because surprise billing may occur when a consumer is unknowingly treated by a provider outside of the consumer's health insurance plan's network, surprise billing proposals may include a variety of requirements that would seek to provide consumers with more information about the providers in their network and/or the care they are to receive in order to make an informed decision about their medical care providers. Such requirements alone would not eliminate surprise billing but could reduce the prevalence of unexpected out-of-network use, which in turn would decrease the prevalence of surprise billing.49

The effectiveness of such provisions in reducing surprise billing is tied to the extent to which consumers can use the new information to decide whether to receive services from an out-of-network provider (e.g., consider information utilization in emergency situations).

Notification

In the surprise billing context, consumer notifications typically are discussed as a way to provide various pieces of information (e.g., about provider network status and estimates of related financial responsibilities) to consumers prior to the receipt of services so consumers can make informed decisions about their medical care providers. This type of requirement can apply to insurers, providers, or both.

If considering a notification requirement, policymakers may want to identify what information should be included within a notification requirement. For example, the notification may be structured to include the provider's and/or facility's network status, the estimated costs of the services, the provider's ability to bill the consumer for amounts other than plan cost-sharing amounts, or any other piece of information that policymakers feel needs to be provided to consumers.50 In addition, policymakers may want to address who is responsible for providing the notice to the consumer (i.e., insurer or provider), when the notice must be provided to the consumer, and if and when the consumer must provide consent to the notice.

Notice requirements should account for any limitations on the types of services and settings that would be subject to such requirement and the consumer's ability to use (and, where applicable, consent to) such information (e.g., emergency situations or complications mid-procedure). Furthermore, any notification requirement should account for whether the insurer or provider subject to the notification requirement has access to the information that is required to be included in the notice.

A notification requirement may be coupled with consumer financial liability protections. For example, some federal proposals apply consumer financial liability protections in some surprise billing situations (e.g., non-emergent care) only when a provider does not adhere to a corresponding notification requirement.

Provider Directories

Provider directories contain information for consumers regarding the providers and facilities that are in a plan network. Provider directory requirements may fall on insurers and providers.51 Insurers typically are responsible for developing and maintaining the directory; however, the information used to populate the provider directory typically comes from the providers.

If considering provider directory requirements, policymakers may want to identify what information is included in the directory, how the information is made available to the consumer (e.g., posted on a website), and how often the directory needs to be updated or verified.

A provider directory requirement may be coupled with consumer financial liability protections. In these instances, policymakers may consider how financial liability protections would interact with provider directory requirements. For example, financial liability protections could be limited to situations where a consumer receives services from a provider based on incorrect provider directory information.

What Types of Requirements Could Be Placed on Insurers, Providers, or Both?

In considering surprise billing proposals, there has been debate around how to shield consumers from receiving unexpected and likely large bills from out-of-network providers that the consumer did not have the opportunity to choose while balancing the impact of establishing a method for ensuring payment for those services. Proposals to address surprise billing situations have generally sought to address the lack of a contractual relationship between insurers and out-of-network providers by establishing standards for determining the total provider payment and the insurer payment net of specified consumer cost sharing. Other methods have sought to create network requirements that would reduce the probability that a consumer would be treated by an out-of-network provider at an in-network facility.

The following sections will discuss these different types of requirements.

How Could a Proposal Address Insurer and Provider Financial Responsibilities in Surprise Billing Situations?

As discussed in the "Private Health Insurance Billing Overview" section, in general, payment for out-of-network services depends on whether the plan covers out-of-network benefits. Regardless of whether or not a plan provides out-of-network benefits, there is no contract establishing a set payment rate between an insurer and an out-of-network provider. If an insurer provides out-of-network benefits, the insurer determines the amount it will pay and the provider can balance bill consumers. If an insurer provides no out-of-network benefits, the insurer will not pay anything toward the out-of-network service. Both scenarios are subject to state and federal law that may define the amount insurers pay out-of-network providers in certain situations (e.g., federal requirements related to emergency services, state surprise billing laws).

Most federal proposals in the 116th Congress to address surprise billing situations include provisions establishing methodologies for determining how much insurers must pay out-of-network providers in specified surprise billing situations. To date, proposals have focused on two main methods for determining the financial responsibility of insurers. One approach has been to select a benchmark payment rate that would serve as the basis for determining a final payment amount that a provider must be paid for a service. The other approach has been to establish an alternative dispute resolution process, such as arbitration, with provider payment determined by a neutral third party.52 The final payment amount determined by either approach may affect consumer cost sharing to varying degrees based on a consumer's plan. For example, under a plan that has a coinsurance to determine a consumer's cost sharing for a service, rather than a co-payment, the amount that the consumer would be responsible for would depend on the final payment rate for a service.

In addition to discussing the benchmark and arbitration approaches, this section includes a discussion on using a bundled payment approach. In this approach, an insurer makes one payment (net of cost sharing) to a facility, and that facility then is responsible for paying providers practicing within the facility. Following that discussion will be a section on the possibility of establishing network requirements to address surprise billing situations, including network matching.

When considering a proposal that establishes a method for determining payment rates, policymakers may want to consider a number of factors; these factors include, but are not limited to, the potential effects on the financial viability of providers and the financial impact on health insurers, which in turn may affect health insurance premiums. This may include consideration of the cost and burden associated with establishing payment rates and the predictability of each method for determining payment rates. In addition, policymakers may want to consider the extent to which these payment models would apply uniformly to all types of plans, services, and/or providers. The various options all have trade-offs, and the relative effect of a given proposal on providers and insurers might vary depending on the local health care market structure. A full assessment of the different choices is beyond the scope of the report.

Policy solutions for surprise billing situations that involve setting out-of-network payment rates may have secondary effects that result from potential changes in relative leverage between insurers and providers. For example, a proposal that would establish higher out-of-network rates than in-network rates previously agreed upon between providers and insurers for certain services may encourage some providers to go out of network or remain out of network to obtain the higher rate. This may lead insurers to raise in-network rates for these services to incentivize providers to join networks. If this response subsequently leads to higher average in-network rates as well as out-of-network rates (along with increased out-of-network coverage), then it may result in higher premiums in the market. Conversely, if the proposal lowers out-of-network payment rates below in-network rates previously agreed upon between providers and insurers, the proposal may increase the amount of leverage insurers have when negotiating with providers for network inclusion, creating downward pressure on in-network payment rates.

Benchmark Approach

Federal surprise billing proposals that use a benchmark approach involve tying payment to a reference price, such as Medicare rates or market-based private health insurer rates. A benchmark-based surprise billing proposal would be structured to specify one or more benchmarks and a methodology for calculating a final payment rate.53

Medicare as a Benchmark

Some recent federal proposals would require insurers to pay an out-of-network provider a rate tied to the payment for that service under Medicare. Studies have shown that Medicare rates for physician services provided by specialists most often involved in surprise billing situations (e.g., pathology, anesthesiology, radiology) generally are lower than commercial rates paid by insurers in the private health insurance markets.54 Policymakers seeking to adjust for the differences between Medicare and commercial rates may structure payment as a percentage of Medicare rates. For example, some surprise billing state laws establish private health insurance rates for certain services at Medicare plus an added percentage.55

Market-Based Benchmark

As compared with a Medicare benchmark approach, a market-based benchmark approach may raise different questions that need to be considered in order to determine the most appropriate reference price on which to base payment. Determining the market data that will provide the foundation for a benchmark for out-of-network payment rates is critical, as the effect may go beyond setting out-of-network payment rates. The distribution of data, which can vary, may have an anchoring effect on the negotiation of in-network payment rates. For example, a proposal that relies on a benchmark that would result in out-of-network payment rates below current in-network payment rates for some providers may shift the negotiating leverage in favor of insurers, which may then use the threat of the lower out-of-network rate to negotiate lower in-network rates. If a proposal results in higher out-of-network payment rates than in-network payment rates for some providers, the leverage to negotiate will shift toward providers, who may demand higher in-network payment rates.

Policymakers may need to decide whether to base the benchmark on provider charges or insurer payment rates. Provider charges are the amounts that providers charge a consumer and/or insurer for a furnished service. These amounts generally will be higher than the negotiated amounts, because they do not include any discount negotiated between insurers and providers. There are no federal proposals that rely on provider charges as a benchmark for setting payment for services provided by out-of-network providers. There are federal proposals using a benchmark approach that rely on private insurer in-network payment rates.

Insurer payment rates could be specified as an insurer's usual, customary, and reasonable (UCR) rates or as an insurer's in-network contracted rates. UCR rates are a method that insurers use to determine payment to providers for out-of-network services if a plan provides out-of-network benefits. Insurers have discretion over how UCR rates are calculated, and such determinations vary from insurer to insurer. In-network contracted rates are the payment rates determined either through negotiation between insurers and providers for in-network services or based on a fee schedule developed by an insurer; a provider must agree to this fee schedule for inclusion in the insurer's network.

Once policymakers establish whether a proposal uses provider charges or insurer payment rates, they may specify a methodology for determining the final payment rate. For example, a policy proposal may specify a mean, a median, a percentage, or a percentile of the benchmark rate. The most appropriate metric will depend on the underlying distribution of the benchmark data being used and how the resulting payment rate compares with current in-network and out-of-network rates.56

To the extent that a benchmark is based on market-based rates, policymakers may want to consider whether to limit the rates included in the benchmark to a specific geographic area to account for the variations in the underlying cost of health care services in different communities. However, a geographic region that is too large may not account for the discrepancies between markets within the region—for example, rural and urban health care costs—and a geographic region that is too small may result in situations where only one particular provider or insurer is included.

Policymakers also may want to consider whether to set a benchmark based on current payment data or on historical payment rates combined with an inflation factor. Using historical rates may mitigate potential fluctuations in in-network rates in response to implementing a surprise billing approach, including changes in network strategies by insurers or providers looking to influence future payments. However, using historical rates may not, depending on the data used, account for material changes in a local health care market (e.g., changes in technology, market consolidation, etc.).

Finally, there may be situations in which an insurer does not have the appropriate data to determine payment rates under a market-based benchmark. For example, an insurer that is a new entrant to a market will not have established in-network payment rates for past years. In such a case, the new entrant may have to rely on public or privately run databases that aggregate payment rate data of other insurers in a market to determine an average in-network rate for a particular provider type in a particular geographic area. Given such a situation, policymakers may want to consider whether to specify a source of data, whether public or private, for reference prices an insurer may use to calculate payment rates or a set of standards for databases that an insurer may use to establish payment rates. The quality and breadth of the data may affect the degree to which reference prices accurately represent the market and population. Currently, there is no universal source of data for all market types and insurers. Some states operate all-payer claims databases (APCDs); of the states that have APCDs, a subset of the APCDs are voluntary initiatives that may not collect data from all insurers in the state.57 However, state APCDs cannot require the collection of data from self-insured group health plans.58

Multiple Benchmarks

Proposals may specify multiple benchmarks. In these types of proposals, multiple benchmarks may be used to establish guardrails (i.e., a floor or a ceiling) to counterbalance the potential anchoring effects of a single benchmark discussed earlier.

There are different methodologies for determining which benchmark would apply in a surprise billing situation. The methodology may involve choosing whether the payment should be based on the greatest or least among the various benchmarks. If using a greatest of approach, then the insurer would be responsible for paying a rate to a provider based on the benchmark that results in the highest payment rate among the various specified benchmarks. A least of approach would make an insurer responsible for paying a provider a payment rate that is based on the benchmark that results in the lowest payment rate among the various specified benchmarks. For example, an insurer may be required to pay a provider a percentile of UCR or, at a minimum, a percentage of Medicare.

Alternative Dispute Resolution

Some federal surprise billing proposals from the 116th Congress have considered an alternative dispute resolution process, such as arbitration. In an arbitration model, the provider and the insurer would submit proposals for payment amounts to a neutral third party. The third party would then determine, on a case-by-case basis, the total amount to be paid to the provider, which would include the insurer payment and the consumer cost sharing. The cost-sharing parameters would be determined under the proposal, not by the arbitrator, and would depend on the cost-sharing structure of the consumer's health plan. However, the rate set by the arbitrator can affect the amount paid by the consumer. The arbitration model might provide more flexibility than the benchmark in that payment would not be fixed based on a reference price. However, it might involve more administrative costs to determine payment rates on a case-by-case basis and would provide less predictability regarding payment rates for out-of-network services.

As arbitration relies on a third party to decide payment, proposals typically establish criteria for determining who may act as an arbitrator. Criteria may include a conflict-of-interest standard to ensure the third party does not have an interest in the process's outcome.

Policymakers also may want to consider whether to establish standards for when insurers or providers may elect arbitration. Standards may be structured to require a minimum amount of time after a provider has billed for a service before either the provider or the insurer may seek arbitration to settle a payment dispute. This approach would afford providers and insurers an opportunity to negotiate a payment rate.

In addition to a time requirement, policymakers seeking to limit resources expended on arbitration may consider establishing a threshold requirement to prohibit providers and insurers from seeking arbitration for charges under a certain dollar amount. If a proposal does not include a threshold requirement, then providers and insurers would be able to seek arbitration for any surprise billing payment dispute. The requirement may be structured to provide a specific amount, which may include a method for adjusting the amount year to year to account for inflation. Alternatively, policymakers could choose to provide authority to agencies to establish a method for determining the threshold amount.

If a threshold requirement is set in a way that prohibits parties from seeking arbitration below a certain dollar amount, then policymakers may want to consider how to address payment for amounts under the threshold. A proposal could be structured to require insurers to pay any charges under the threshold amount, or a benchmark, as described earlier, could be used on a limited basis for any charged amounts under the threshold.

Once it is determined who may seek arbitration for a surprise billing dispute, policymakers may want to consider how to structure the arbitration process, including how an arbitrator decides payment. One possible approach, taken by the state of New York, would be to institute a baseball-style arbitration process in which each party submits its best and final offer to the arbitrator, who then decides which offer to accept as the final payment rate. Another possibility would be to provide the arbitrator with the flexibility to decide a final payment rate that may differ from the proposals submitted by the parties to the arbitration. Regardless of the flexibility given to the arbitrator, policymakers may want to consider specifying factors that the arbitrator should take into account when making a final decision.

Hybrid Approach

It is possible to combine the benchmark and arbitration approaches. For example, in response to stakeholder concerns regarding the use of particular methods for determining final payment amounts, some states and one federal proposal pair the use of a benchmark with the option of arbitration if either party is not satisfied with the payment rate established by the benchmark.59 Another hybrid approach could involve establishing an arbitration process in which the arbitrator picks one amount from a list of benchmarks to establish a final payment rate.

Bundled Payment Approach

Some researchers have proposed a bundled payment approach as an alternative to establishing how much an insurer must pay directly to an out-of-network provider.60 Instead of regulating the relationship between an insurer and the out-of-network provider, a bundled payment approach would focus on the insurer and the facility in which the service was provided. An insurer would make one payment to the facility, after which the facility would be responsible for paying providers for services provided in the facility. Instituting a bundled payment would shift the onus from the out-of-network provider to the facility to negotiate with the insurer for a bundled rate. It would then be the facility's responsibility to negotiate with the providers for payment of services provided within the facility. Currently, no federal proposals or state laws use a bundled payment approach to address surprise billing.

How Could a Proposal Address Network Requirements?

An alternative to focusing on payment for out-of-network services would be to reduce the probability that consumers would inadvertently receive care from out-of-network providers. An alternative to setting a benchmark or establishing an arbitration process would be to set network requirements.

Network Adequacy Requirements

Network adequacy is a measure of a plan's ability to provide access to a sufficient number of in-network providers, including primary care and specialists. In the individual and small-group markets, states have been the primary regulator of plan networks and have network adequacy standards for most health insurance plans. The ACA created a federal network adequacy standard.61 However, the federal government defers to states to enforce network adequacy standards.62 Self-insured plans are not subject to network adequacy standards.

Instituting stricter network adequacy standards (i.e., requiring plan networks to include a larger number of providers of varying types) may not address all surprise billing situations. Unless network adequacy standards require all providers to be in network, they do not guarantee that insurers will contract with every provider that a consumer may see, especially in situations where a consumer travels outside the plan's service area.63

Network Matching

Some researchers have proposed another network-based approach, referred to as network matching, which would involve the creation of an in-network guarantee to address surprise billing situations in which consumers receive care from out-of-network providers in in-network facilities.64 An in-network guarantee would ensure that a facility and the providers practicing in that facility contract with the same insurers to be included in the same networks. However, surprise bills might still occur in the case of emergency services, when consumers may not have the option to choose an in-network facility, especially when a consumer travels outside the service area of his or her health plan. No current federal proposals or state laws use a network matching approach to address surprise billing.

An in-network guarantee could be structured in a few ways. Policymakers could create an in-network guarantee that applies to insurers and would prohibit insurers from contracting with a facility unless the facility guaranteed that all providers practicing in the facility would contract to be in the same networks as the facility.

Another way to structure an in-network guarantee would be to prohibit the insurer from paying out-of-network providers for any services provided to the consumer in an in-network facility. When paired with a prohibition on balance billing, a provider that was previously not incentivized to be in network because of the possibility of higher out-of-network payments might be incentivized to negotiate with an insurer to be included in plan networks to obtain payment beyond consumer cost sharing.

How Could Surprise Billing Requirements Be Enforced?

To the extent a surprise billing proposal imposes any prohibitions or affirmative obligations on the insurer, the provider, or both, a question remains as to how to enforce any such limits or requirements. The current legal framework for enforcing discrete requirements for insurers and providers may be a template for Congress to consider when drafting surprise billing legislation. Potential enforcement mechanisms include authorizing the Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS) and/or the Secretary of Labor—depending on the plan type65—to bring enforcement actions or allowing private entities to seek a right of action in a court against a regulated entity.66 An enforcement scheme also may attach specified statutory penalties to a violation of the statute.67 Depending on whether a surprise billing proposal amends an existing statute, these options may be included as the principal enforcement mechanism or could be added to supplement any existing enforcement schemes.

Current Enforcement Mechanisms on Private Health Insurance Issuers

A number of federal surprise billing proposals would amend provisions (including the emergency services provision) under Part A of Title XXVII of the Public Health Service Act (PHSA).68 This part of the PHSA, as amended by the ACA, was incorporated by reference into Part 7 of the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA) and Chapter 100 of the Internal Revenue Code (IRC).69 As a result, these three statutes' existing enforcement mechanisms may be relevant to any additional prohibitions or requirements added to Part A of Title XXVIII of the PHSA by a surprise billing proposal. Existing enforcement provisions under these statutes currently apply only to insurers and not to providers.70

Public Health Service Act

In general, the existing enforcement provisions for Title XXVII of the PHSA's requirements apply to health insurance issuers in the group and individual markets and to self-funded nonfederal governmental group plans.71 With respect to health insurance issuers, states are the primary enforcers of the PHSA's requirements.72 If the HHS Secretary determines that a state has failed to substantially enforce a provision of Title XXVII of the PHSA with respect to health insurance issuers in the state,73 or if a state informs the Secretary that it lacks the authority or ability to enforce certain PHSA requirements, the Secretary is responsible for enforcing these provisions.74 In the event that federal enforcement is needed, the HHS Secretary may impose a civil monetary penalty on insurance issuers that fail to comply with the PHSA requirements.75 The maximum penalty imposed under PHSA is $100 per day for each individual with respect to which such a failure occurs,76 but the Secretary has the discretion to waive part or all of the penalty if the failure is due to "reasonable cause" and the penalty would be excessive.77

Employee Retirement Income Security Act

Part 7 of ERISA currently includes various requirements for (1) group health plans, which generally consist of both insured and self-insured plans providing medical care that an employer establishes or maintains, and (2) health insurance issuers offering group health insurance coverage.78 ERISA provides two general enforcement mechanisms for these requirements. First, the Secretary of Labor may initiate a civil action against group health plans of employers that violate ERISA, but the Secretary may not enforce ERISA's requirements against health insurance issuers.79 Second, Section 502(a) of ERISA authorizes a participant or beneficiary of a plan to initiate certain civil actions against group health plans and health insurance issuers.80 Plan beneficiaries may, for instance, bring actions against the plans to recover or clarify their benefits under the terms of the plans.81

Internal Revenue Code

In general, the group health provisions in Chapter 100 of the IRC apply to all group health plans (including church plans), but they do not apply to governmental plans and health insurance issuers.82 Under the IRC, the group health plan requirements are enforced through the imposition of an excise tax.83 Failure to comply with an IRC requirement generally would subject a group health plan to a tax of $100 for each day in the noncompliance period with respect to each individual to whom such failure relates.84 Limitations on a tax may be applicable under certain circumstances (e.g., if the person otherwise liable for such tax did not know, and exercising reasonable diligence would not have known, that such violation existed).85 Failure to pay the applicable excise tax may result in further penalties, and a dispute regarding any penalty liabilities may be resolved by a proceeding before a U.S. district court or the Court of Federal Claims.86

Current Enforcement Mechanisms on Providers

As noted above, the PHSA, ERISA, and IRC currently do not include enforcement provisions that apply to providers; instead, the applicable statutes impose requirements on only the relevant group health plans and health insurance issuers.87 Indeed, because the regulation of medical providers is traditionally within the province of the states, federal law has generally limited its role in regulating providers to specified circumstances.88 To the extent any federal requirements are imposed on providers, the requirements generally are enforced through provisions specific to the applicable regulatory framework.89 The enforcement provisions applicable to federal health care programs (including Medicare and Medicaid), for instance, authorize the HHS Secretary to initiate enforcement proceedings against any person (including a health care provider) for certain specified violations, including the submission of improperly filed claims and the improper offer or acceptance of payments to reduce the provision of health services.90 Violators may be subject to civil penalties, be excluded from further participation in federal health programs, or both.91 Thus, to the extent a surprise billing proposal would impose specific limits or requirements directly on providers, policymakers may want to consider enforcement provisions specific to those regulatory requirements.

Consistent with this approach, many federal surprise billing proposals to date—particularly if they would amend Part A of Title XXVII of the PHSA—include enforcement provisions that would apply specifically to providers in this context.92 The proposals generally would limit the application of these enforcement provisions to providers who have not been subject to an enforcement action under applicable state law.93

How Could a Federal Surprise Billing Proposal Interact with State Surprise Billing Laws?

As discussed in the "State Requirements" section of this report, many states have enacted laws that address surprise billing in various situations and incorporate different policies discussed throughout this report. Given the likely overlap between state laws and any potential federal laws, policymakers may want to consider how federal surprise billing policies should interact with related state laws. In other words, policymakers may want to determine which laws are applicable in situations addressed by both federal and state laws. They may opt to have federal law defer to state law, have federal law preempt state law, or some combination thereof. To date, many federal proposals have included language that would maintain state surprise billing laws and would apply federal law only in instances where states do not have such laws.

In the event that a federal surprise billing law would provide deference to state surprise billing laws, it may be worth considering how such deference would be provided. For example, a federal proposal that addresses ambulances may be drafted so that federal law does not apply in any state with any type of surprise billing law, regardless of whether such state law addresses ambulances. As mentioned earlier in this report, state surprise billing laws have varied in their application to different situations and/or providers, and some states have only applied surprise billing laws and regulations to a narrow set of situations. For example, surprise billing protections in Arizona, Massachusetts, Missouri, New Hampshire, and Oregon apply only for emergency services provided by an out-of-network provider at in an in-network hospital.94 Therefore, this type of federal ambulance surprise billing law would not apply in those states.

It is also possible that a federal surprise billing law would apply only to services, situations, and plans that have not been addressed by state surprise billing laws (or have been addressed in a manner that does not satisfy criteria included within such proposal). This type of policy would likely result in multiple different ways to handle surprise billing situations within a state. For example, fully insured plans could be subject to state laws and self-insured plans could be subject to federal laws.95 As a result, enrollees of different types of plans may have different protections in surprise billing situations.96 The extent of the aforementioned discrepancy would correspond to the extent to which state residents are enrolled in a self-insured plan. For reference, in 2017, Hawaii had the lowest percentage of private sector employees enrolled in a self-insured plan at an employer offering health insurance coverage (31.2%) and Wyoming had the highest percentage (72.4%).97 The national average was 59.4% in 2017.98

This difference can also be highlighted in the context of the interactions between surprise billing protections in Arizona, Massachusetts, Missouri, New Hampshire, and Oregon, which apply only for emergency services provided by an out-of-network provider at in an in-network hospital, and a hypothetical federal policy that applies to emergency services generally and provides deference to state laws. In this example, state law would apply to emergency services provided by an out-of-network provider at an in-network hospital and federal law would apply to emergency services provided by an out-of-network provider at an out-of-network hospital.

Considering that a surprise billing federal policy would affect insurers, providers, or both and could alter these parties' incentives to enter into network agreements together (see "Potential Policy Impacts"), the combination of a federal policy with varying state policies would likely result in a unique set of incentives for insurers and providers within each state.

By contrast, a federal surprise billing law may be structured so that state deference is not provided. Under this type of proposal, a federal surprise billing law would be uniformly applicable to all states, regardless of previous state surprise billing legislative action.

In addition to considering the relationship between state and federal surprise billing laws, policymakers may want to incorporate policies that provide states with opportunities to tailor a federal proposal. For example, a federal policy could allow states to select the benchmark parameter used for plan payments out of a list included in the federal policy, or a federal policy could allow states to further determine the information included in a notification requirement. Such provisions would provide states with the ability to determine how best to incorporate federal policies given the relationship structure between insurers, providers, and consumers within that state.

Potential Policy Impacts

Since policy decisions rarely occur in a vacuum, many of the aforementioned policy considerations directly affect one (or multiple) aspects of the billing process.

These impacts can be considered narrowly, by looking at how specific actors (i.e., insurers, providers, and consumers) may respond to such policy considerations. For example, consider the effects of a federal policy that (1) establishes a benchmark reimbursement rate that is lower than what insurers currently typically pay out-of-network providers for a specific service provided to consumers and (2) prohibits balance billing.

From the insurer's perspective, an insurer may decide to lower premiums for plans that cover out-of-network benefits if its net payments to providers decrease after adjusting for any changes in consumer cost sharing under the policy. Relatedly, to the extent that such policy requires insurers to cover a portion of other consumer costs for specific services, insurers may choose to increase premiums on plans that do not cover out-of-network benefits to cover these additional costs.

From the provider perspective, impacted out-of-network providers may see a reduction in revenue from the lower payment rate and the prohibition on balance billing consumers for those services. The provider also may see a reduction in the administrative costs associated with being an out-of-network provider (e.g., costs associated with communicating with and collecting payments from numerous consumers and/or insurers, costs associated with failure to collect payments from consumers). Depending on the extent to which the provider is affected, the provider may respond to this example federal policy by adjusting the prices of other services not affected by the policy or adjusting what services are offered.

A different surprise billing policy that would establish an arbitration process could create greater administrative costs for insurers and providers. These costs could subsequently be incorporated into premium prices or provider charges for services.99

Policy impacts also can be considered more generally by identifying how these policies could alter the relationships between insurers, providers, and consumers. For example, policies that require insurers to pay providers specified amounts for out-of-network services might affect contract negotiations between insurers and providers.

If a proposal required insurers to pay out-of-network providers their median in-network rate for services, insurers might be incentivized to reduce rates for those providers earning above the median amount or be less likely to contract with such providers during subsequent contract negotiations. If insurers did not contract with such providers, the provider would be considered out of network and the plan would pay providers the plan's median rate for services included in the surprise billing proposal. Inversely, providers earning below the median rate might be likely to demand increased payment rates or to consider dropping out of the network, the latter of which would result in those providers also being paid at a plan's median rate. Together, if insurers and providers responded accordingly, a plan's payment rates for the specified services included in a surprise billing proposal would move to the median rates for both in-network and out-of-network providers.

If a proposal required insurers to pay out-of-network providers based on an arbitration model (i.e., dispute resolution process), then some providers that furnish specialized services or work on complex cases might be more likely to demand increased payment rates. This could occur because these providers would otherwise be more likely to receive results that are more favorable as an out-of-network provider participating in an arbitration process that considers the extent of the provider's expertise and the complexity of each case.

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimated the net effects of these types of policies on insurance premiums and the related effects on the federal budget in its scoring of two surprise billing bills from the 116th Congress (S. 1895 and H.R. 2328, which are compared in the Appendix).100