Introduction

This report focuses on remittances, transfers of money and capital sent by migrants and foreign immigrant communities to their home country. Increasing migration is a defining feature of the current global economy. According to the United Nations, the number of international migrants reached an estimated 272 million in 2019.1 The United States has more immigrants than any other country in the world, 44.7 million in 2017.2 Immigrants account for 13.6% of the U.S. population, triple the share in 1970 (4.7%).3

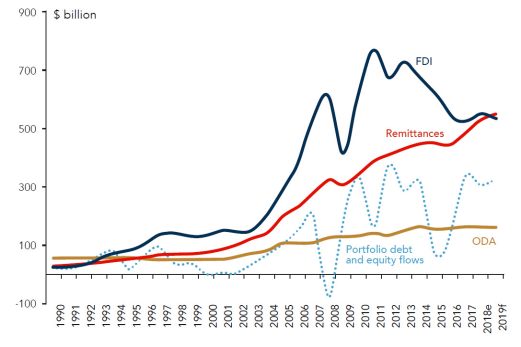

As migrants have become more integrated into the global economy, their involvement in the economic activities of their home countries has also increased. In 2019, worldwide remittance flows are estimated to exceed $707 billion. Of that amount, low- and middle-income countries are estimated to receive about $550 billion, nearly three times the amount of official development assistance (ODA).4 Only foreign direct investment (FDI) is a comparable source of foreign capital for the world's developing countries than remittances.5

The dramatic rise in the importance of remittances to global capital flows has led Congress and other policymakers to take a greater interest in these flows and how they are covered under U.S. and state regulation. For example, P.L. 111-203, the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, provided federal consumer protections on remittance transactions. Remittances are also subject to federal regulation to prevent money laundering and terrorist financing.

This report provides general background on remittances, analyzes global and U.S. remittance flows, examines the remittance marketplace and the regulatory regime for sending remittances from the United States, and discusses key issues for Congress.

Background

Remittances are cross-border migrant financial transfers. The primary source for international remittances data is the International Monetary Fund (IMF), which compiles statistics submitted by its member countries. Using IMF statistics, the World Bank publishes migration and remittances data on its website.6

Remittances are defined as the sum of three entries in the IMF's annual Balance of Payments Statistics Yearbook: workers' remittances; compensation of employees; and migrants' transfers.7

- Workers' remittances are defined by the IMF as transfers (cash or in kind) by migrants who are both employed and considered resident in another country. If the migrants live in the host country for one year or longer, they are considered residents, regardless of their immigration status.

- Compensation of employees includes wages, salaries, and other benefits of border, seasonal, and other nonresident workers (such as local staff of embassies) away from their home country for less than a year.

- Migrants' transfers are the net worth of migrants' assets that are transfers from one country to another at the time of migration (for a period of at least one year), such as in the case of temporary workers.

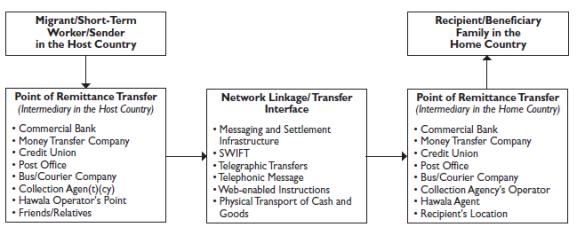

A remittance transaction typically involves a sender, a recipient, intermediaries in both countries, and a payment system used by the intermediaries (Figure 1).8 Remittances can be sent through informal or formal channels. Informal channels have been labeled by various terms, including "alternative remittance systems," "underground banks," and "informal value transfer systems." The most well-known is hawala (hawala means "transfer" in Arabic), which originated in India and has been in use in South Asia and the Middle East for several hundred years.9 These services are less expensive than formal banking or money transfer arrangements, can provide anonymity for all parties involved, and can reach countries where there is no formal banking sector, in some cases even arranging for hand delivery of the cash. While most use these systems for legitimate purposes, their lack of documentation and their anonymity and informality may make them attractive for money laundering, terrorist financing, or other illegal purposes.

Formal channels involve intermediaries that are officially licensed to operate money transfer businesses. These consist of banks; nonbank financial institutions, such as credit unions, savings and loan institutions, and post offices; and money service businesses such as Western Union or MoneyGram. Increased use of technology in developing countries has also facilitated the use of mobile-phone-based and other electronic payment methods.

|

|

Source: International Transactions in Remittances: Guide for Compilers and Users, International Monetary Fund, 2009. Notes: Not all transactions sent through these channels are remittances. |

The price of sending a remittance can vary significantly. A number of factors affect the transfer fee charged, including the regulatory and administrative costs, the volume sent, the transfer mechanism, the receiving country's financial infrastructure, and the level of market competition (in both the sending and receiving country). In addition, the exchange rate used in the transaction can significantly affect the amount actually delivered to the recipient.

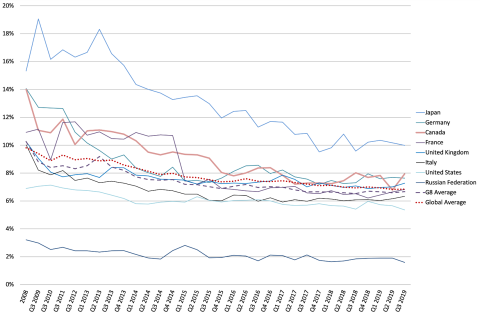

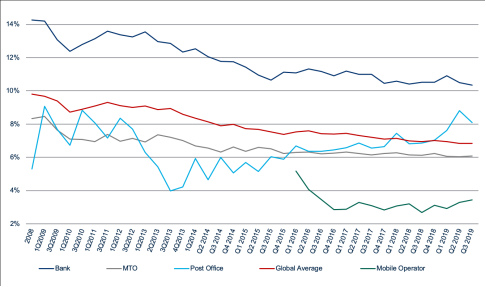

For the most part, the cost of sending remittances has declined slightly in recent years, but substantial progress would be needed to meet the G8 target of 5% of total cost set in 2009. According to World Bank analysis, the global average remittance cost has declined from 9.81% of the total transaction in 2008 to 6.84% during the third quarter of 2019.10 Among the major economies, the United States is among the least costly from which to send money (Figure 2). For the first quarter of 2016, the average cost to send a remittance from the United States was 6.04% of the transaction.11 The World Bank also tracks the cost of sending remittances from the main remittance providers. Recent data show that banks continue to be the most expensive providers, followed by post offices. Mobile Operators and Money Transfer Operators (MTOs) such as Western Union and Moneygram are the cheapest (Figure 3).

|

Figure 2. Total Average Cost of Sending Remittances from G8 Countries |

|

|

Source: Remittance Prices Worldwide, the World Bank |

|

Figure 3. Total Cost to Send Remittances by Service Provider |

|

|

Source: Remittance Prices Worldwide, the World Bank |

Global and U.S. Remittance Flows

Remittances have increased steadily over the past three decades and are the largest source of external finance for many countries (Figure 4). In 1990, remittances to low- and middle-income countries totaled about $75 billion and are expected to reach $551 billion in 2019. Official remittance figures do not include informal remittance flows, which may account for an additional 35% to 75% of total remittance flows.12 In 2019, India was the largest remittance-receiving country ($82.2 billion), followed by China ($70.3 billion), and Mexico ($38.7 billion). Figure 4 shows the geographical distribution of remittances since 2000.

|

Figure 4. Remittances to Developing Countries, by Region, 2000-2019 In Billions of U.S. Dollars |

|

|

Source: World Bank, World Development Indicators |

The emergence of large Indian, Chinese, and Philippine diaspora populations led to the explosive growth of remittances over the past 15 years. Between 2000 and 2014, remittances to developing countries in East Asia and Pacific increased by 370%, growing from $17 billion in 2000 to $79 billion in 2014. In South Asia, remittances increased by 571% over that time, growing from $17 billion in 2000 to $116 billion in 2014. Despite accounting for a much smaller amount of global remittances, flows to Sub-Saharan Africa increased by 608% from 2000 ($5 billion) to 2014 ($34 billion).

The IMF, World Bank, and the U.S. government do not compile and publish remittance flows from the United States (or other countries) to individual countries or regions. However, since 2010, the World Bank has estimated bilateral remittance flows between its member countries.13 Table 1 presents the World Bank's estimates for the largest recipients of remittances from the United States from 2010 to 2018 and Table 2 presents the ten largest remittance corridors in 2018. The United States is the largest sending jurisdiction, accounting for 23.27% of all remittances sent in 2018 and originating remittances in seven of the ten largest corridors.

|

2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

Mexico |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

China |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

India |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

Philippines |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

Vietnam |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

Guatemala |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

Nigeria |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

El Salvador |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

Dominican Republic |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

Honduras |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Source: World Bank, Bilateral Remittances Matrices, various years

|

Receiving Country |

Remittance Estimate ($ billions) |

|

|

United States |

Mexico |

34.7 |

|

United Arab Emirates |

India |

18.53 |

|

Hong Kong |

China |

16.34 |

|

United States |

China |

14.25 |

|

United States |

India |

12.74 |

|

Saudi Arabia |

India |

11.67 |

|

United States |

Philippines |

11.43 |

|

United States |

Guatemala |

8.49 |

|

United States |

Vietnam |

8.33 |

|

United States |

Nigeria |

7.27 |

Source: World Bank, 2018 Bilateral Remittance Matrix

The U.S. Remittance Marketplace

Money Service Businesses (MSBs)

Currently, the U.S. foreign remittance market is dominated by MSBs, a category of nonbank financial institutions that generally own proprietary, so-called "closed-loop" payment systems and operate largely outside of conventional banks.14 The capacities of MSBs include issuing money orders and traveler's checks, transmitting money, cashing checks, exchanging currency, dealing currency, and storing value.15 MSBs cover a broad variety of enterprises ranging from small and simple operations to large firms. MSBs include the U.S. Postal Service, because it issues money orders. Western Union and MoneyGram are the two largest money transmission companies and their agents are often located in a wide variety of other businesses, including supermarkets, check cashing agents, gas stations, liquor stores, convenience stores, and currency exchange offices. The main reason foreign remittance customers use MSBs is that they are often "unbanked"; that is, they do not have an account with a depository financial institution. In addition, money transmission services may be an ancillary service: the foreign remittance customer may be able to cash a paycheck, send money to family in his home country, and shop for groceries at the same location.

Traditional Financial Institutions

Remittance transactions are not a service traditionally provided by banks. International money transfer services provided by banks are expensive, and have thus been marketed primarily to corporate clients who send larger amounts than a typical migrant remitter. According to the Federal Reserve, the median amount of a consumer-initiated wire transfer processed by financial institutions is about $6,500 in domestic and foreign transfers, much larger than most remittance transactions, which are typically a few hundred dollars.16 Another constraint for bank provision of remittances is the underdeveloped financial systems in many of the largest remittance-receiving countries. Since many recipients lack a bank account, they prefer to collect remittance money in cash. International wire transfer, however, is only an option when both the sender and receiver have access to deposit accounts at depository institutions. Unlike the "closed loop" payment system used by MSBs, banks and credit unions generally use "open loop" payment systems such as wire-transfer systems and correspondent banking channels. Because they act through retail store locations such as grocery stores, MSBs often have more extensive distribution networks in their countries of operation than traditional financial institutions do.

As consumer demand for remittances has grown over the past two decades, banks and credit unions have shown a greater interest in directly providing remittance services to consumers. Remittance services can be a way to bring low-income migrants into the financial mainstream and introduce them to other financial products and services, such as interest-bearing savings accounts, checking accounts for paying bills (a replacement for money orders), free and secure check cashing services, and small dollar loans, among other services. Credit union participation has also been encouraged by the development of the World Council of Credit Unions' International Remittance Network, a credit union network for international money transfers.

To generate more remittances business, since 1998, U.S. depository institutions have had the option of transmitting remittance transfers through the Automated Clearing House (ACH) system. The ACH system clears and settles batched electronic transfers for participating depository institutions. Since financial transfers are batched together and sent on a fixed schedule, banks can charge a lower price than for traditional international wire transfers, which are sent individually. The originating institution combines the payment instructions from its various customers and sends them in a batch to an ACH operator—the U.S. Federal Reserve Bank's FedGlobal Payments Service or the Clearing House's Electronic Payments Network—for processing. In addition to being used for remittances, international ACH transfers are used for various small recurring cross-border payments, such as social security and other benefit payments; business transactions, such as vendor payments; and consumer transactions, such as bill payments and remittance transfers.

Since 2001, the U.S. Federal Reserve has provided so-called "account-to-receiver" FedGlobal services that allow funds from accounts at a U.S. depository financial institution to be sent to unbanked receivers for retrieval at either a bank location or a trusted, third-party provider. As of 2013, FedGlobal services are available to Europe, Mexico, Panama, and Latin America, covering 35 countries in total.17

Participation in the remittance market by banks and credit unions, while growing, is still limited. The U.S. Federal Reserve does not collect precise statistics on remittance transfers, but reports that in 2014, the two U.S. ACH operators handled 18.3 billion ACH transactions, of which 54.6 million (or 0.3%) were initiated by a business or a consumer, but not by the U.S. government.18

Mobile and Other Emerging Payment Systems

In addition to remittance services provided by MSBs and traditional financial institutions, there has been a proliferation of new companies using new technologies to provide remittances in recent years. Such new options include computer and mobile-based payments;19 pre-paid cards, which can be cashed at an ATM or spent at retail stores;20 directed transfer options in which the sender transmits funds directly to payments on behalf of the recipient;21 and money transfers through social media.22 A study conducted in July 2013 by the World Bank's Consultative Group to Assist the Poor (CGAP) found that there are 41 so-called "branchless" remittance providers in 2013, up from 10 in 2010.23 CGAP also found that traditional remittance providers are introducing flat fees and transparent foreign exchange rates in response to the increased competition.

Regulation of Remittance Providers

At the international level, international standards and principles governing remittances have been set by the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) and the Bank for International Settlements (BIS). In the United States, the operations of U.S. banks and credit unions are closely regulated and supervised at both the state and federal level. Foreign bank branches and agencies are also governed by a combination of state and federal statutes, the provisions of which include licensing requirements and permissible activities. The primary focus of federal regulation is on anti-money laundering (AML) and combating the financing of terrorism (CFT). Individual state regulators, on the other hand, regulate the operations of federally chartered banks and MSBs. Since October 2013, the U.S. Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) has enforced various consumer protection measures included by Congress in the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Consumer Protection Act (Dodd-Frank).

International Standards and Principles

Global standards for remittances emerged over the past decade, largely due to concerns raised about unregulated money transfer services and their use in planning the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks. International efforts have been negotiated at the FATF, an inter-governmental body comprising 34 countries and two regional organizations, including the United States, that develops and promotes policies and standards to combat money laundering and terrorist financing.24 FATF was established in 1989 by the G-7 countries to implement the Vienna Convention Against Illicit Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances, the first international agreement to criminalize money laundering. It is housed at the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) in Paris.

The FATF sets minimum standards and makes recommendations for its member countries. Each country must implement the recommendations according to its particular laws and constitutional frameworks. In 2001, FATF issued nine special recommendations to counter terrorist financing. For example, FATF Special Recommendation VI required FATF member countries to regulate all MSBs. In 2012, FATF revised its recommendations and Special Recommendation VI became FATF Recommendation 14 on Money or Value Transfer Services.25 Several other recommendations are relevant for remittance providers, including recommendation 10 on wire transfers, recommendation 11 on record keeping, recommendation 16 on wire transfers, recommendation 18 on internal controls and foreign branches and subsidiaries, and recommendation 20 on suspicious transaction reporting.26

International efforts have also focused on improving the operational aspects of remittance transfers. In 2007, the BIS and the World Bank jointly issued General Principles for International Remittance Services, to "help to achieve the public policy objectives of having safe and efficient international remittance services, which require the markets for the services to be contestable, transparent, accessible and sound."27 General Principle 3 states that "Remittance services should be supported by a sound, predictable, nondiscriminatory and proportionate legal and regulatory framework in relevant jurisdictions," and affirms the FATF recommendations, advocating that remittance providers comply with all relevant FATF recommendations. FATF maintains a mutual evaluation system and provides oversight of nonmember countries' AML/CFT regimes.

U.S. Anti-Money Laundering/Combating the Financing of Terrorism (AML/CFT) Efforts

In the United States, remittance providers, both banks and MSBs, are required to identify, assess, and take steps to design and implement controls in compliance with their obligations under the U.S. Bank Secrecy Act (BSA). The BSA has been amended a number of times, most notably by Title III of the USA PATRIOT Act in 2001. Among other things, Title III expanded the BSA framework beyond AML to also fight terrorist financing. The main purpose of the BSA is to require financial institutions to maintain appropriate records and file reports that can be used in criminal, tax, or regulatory investigations or proceedings. The Treasury Department's Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) administers the BSA on behalf of Treasury. With limited exceptions, MSBs are subject to the full range of BSA regulatory controls.

Remittance providers must maintain financial records and conduct customer identification procedures for certain transactions. All MSBs must obtain and verify customer identity as well as record beneficiary information for transfers of more than $3,000. They must file Currency Transaction Reports (CTRs), for customer transactions of $10,000 or more in a day, and Suspicious Activities Reports (SARs) for dubious transactions of generally more than $2,000, that the remittance provider "knows, suspects, or has reason to suspect involves funds from illegal activity or is designed to conceal their origin, is designed to evade BSA obligations, or has no apparent business or law purpose."28

Remittances to certain foreign countries may also be subject to sanctions under various federal statutes administered by the Treasury Department's Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC). The U.S. government only restricts remittances on countries, individuals, or companies that are subject to U.S. sanctions and embargoes. Furthermore, the Treasury Department does not have the authority to direct any financial institution to open or maintain a particular account or relationship. The decision to maintain any financial relationship is made by each financial institution itself, while complying with U.S. laws.

Regulatory efforts at the state level focus primarily on consumer protection. Separate from banking regulation and registration, most states have laws requiring that money transmitters be licensed by the state banking agency. Some of these states (usually those with significant immigrant populations) have specific licensing requirements for transmitters sending money to foreign countries. Of the 50 states, only a few states do not require state licenses for MSBs.

"Dodd-Frank" Measures

In response to concerns from U.S. immigrant communities raised during the 110th and 111th Congresses over inadequate disclosure of remittance fees and insufficient consumer protection for remittance transactions, Congress created new consumer protections as part of the Dodd Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (Dodd Frank).29 The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) released on April 30, 2013, a final rule implementing the Dodd-Frank remittance provisions. The effective date of the Final Rule is October 28, 2013.

Under the new law (Section 1073 of Dodd-Frank), a remittance transfer provider must provide consistent, reliable disclosure of the price of a transfer, the amount of currency to be delivered to the recipient, and the date of availability prior to the consumer making any payment. The new requirements also increase consumer protections by requiring remittance providers to investigate disputes and remedy errors related to the transaction.

During the rulemaking process, remittance providers raised concerns about the feasibility of disclosing third-party fees and taxes, which are often unknown prior to the transaction's taking place, and the "error-resolution" provisions, given remittance providers' risk of loss and fraud due to remittance customers' providing incorrect information. To address industry concerns, the CFPB's Final Rule provides greater flexibility for remittance providers on the disclosure of third-party fees and taxes and exempts remittance providers from error remedy procedures due to errors made by the remittance customer, such as providing an incorrect account number for the recipient.30

While the new protections may decrease the cost of remittances over the long run by improving transparency and potentially increasing competition, short-run cost increases may be significant. The increased cost to remittance providers for maintaining up-to-date information on exchange and tax rates of receiving countries and fees charged by third parties may likely be passed on to their customers. The error remedy requirement may also expose remittance transfer providers to potential litigation resulting from fraudulent transactions.31 At the same time, costs for remittance transactions may increase since bank fee income is capped elsewhere.32

Issues for Congress

Key issues on remittances that Members of Congress may want to consider include the following:

Regulation of Remittances

Members may wish to explore the current federal and state regulatory regime for remittance providers and customers. Effective and proportional regulation of remittances can reduce corruption, enhance transparency, and facilitate a more robust business environment. Some observers, however, raise concerns about the costs for remittance providers (and subsequently consumers) of navigating the patchwork of banking and anti-money laundering regulation.33 According to the Federal Reserve:

[R]eports suggest that large depository institutions may be reducing or restricting correspondent banking relationships, which in turn may limit the ability of smaller depository institutions to provide remittance transfer services. Reports also suggest that depository institutions may be terminating the accounts of some nonbank payment providers that offer financial services to consumers, such as money services businesses. Without accounts at depository institutions, some nonbank payment providers may be unable to access the financial system and therefore may be unable to continue providing services, including remittance transfer services.34

Regarding licensing and supervision of remittance providers, recent reform proposals include assigning a single national regulator with responsibility for regulating the entire money transmission business or, at a minimum, increasing coordination and harmonization of state and federal rules on MSBs.35 There have been recent congressional efforts in this direction. For example, in the 111th Congress, Representative Spencer Bachus introduced H.R. 4331, The Money Services Business Compliance Facilitation Act of 2009, which would have established an office of MSB compliance in the U.S. Department of the Treasury, charged with ensuring that state and federal regulators coordinate standards for MSB licensing and registration.

Other legislation has been introduced and passed that aims to facilitate remittances services by making it easier for MSBs to comply with federal and state regulations. The Money Remittances Improvement Act of 2014 (P.L. 113-156), signed into law on August 8, 2014, allows federal regulators, including FinCEN and the IRS, to rely on examinations conducted by state financial supervisory agencies if (1) the category is required to comply with federal requirements, or (2) the state supervisory agency examines the category for compliance with federal requirements. According to Treasury, this legislation "should allow for better allocation of state and federal resources, better targeting of higher risk MSBs, and improved AML/CFT compliance across the [financial] industry."36

Others propose that U.S. policymakers should prioritize access to remittance services for communities with specific needs. This may mean more money for technical assistance to boost the capacity of poorly regulated jurisdictions; one such example is Somalia. In this case, the U.S. Treasury Department could help integrate Somali American MSBs into an ACH payment system; help improve training of MSBs to improve monitoring of their agents; and/or help Somalia regulate its payment systems.37

Members of Congress may wish to examine the impact of the current regulatory regime on the development of emerging payments systems for sending remittances, such as mobile, card, or internet-based models. Some observers argue that current federal and state money transmission laws may be inappropriate for new and emerging payments systems.38 Remittance payments already touch multiple regulatory agencies, and as mobile remittances services increase, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) and the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) will likely play an increasing role. Mobile carriers and other alternative providers are less familiar than MSBs with U.S. and international banking laws, and the lack of U.S. guidance or framework for mobile payments creates coverage, liability, and AML/CFT concerns that Congress may move to explore.39

Members may also pay special attention to the implementation of the "Dodd-Frank" consumer protections following their October 2013 implementation. On one hand, some argue that the new protections will drive down the cost of remitting by requiring greater transparency of fees associated with money transfers. Others argue that the costs of new systems and increased liability for transaction problems will raise costs and deter MSBs and financial institutions from providing remittance services.40

Promoting Remittances as a Development Tool

Members of Congress may consider whether U.S. government efforts on remittances should extend to influencing how they are spent. There are multiple viewpoints on the extent to which the U.S. government should promote remittances as a development tool. Many U.S. development aid officials, for example, are interested in understanding the economic impact of remittances on both the sending and receiving communities and in developing policies to help channel remittances to their most productive use. Others argue that the remittances are foremost an anti-poverty tool, and that policymakers should be cautious about placing too much emphasis on remittances as a development tool or even confusing remittances with foreign aid. Importantly, remittances are a private transaction, and thus any official policy efforts, they argue, should be narrowly focused on reducing the cost of remittance transactions and creating additional opportunities for labor migration.41

Remittances and U.S. Immigration Policy

Members may consider the interplay of U.S. remittance policy efforts and U.S. immigration policy. Some Members of Congress, however, have raised concerns that current customer identification policies, which do not require a remittance customer to provide documentation of legal U.S. immigration status, could undermine efforts to enforce U.S. immigration laws. In light of this concern, in the 114th Congress Senator David Vitter introduced, S. 79, Remittance Status Verification Act of 2015, which would require remittance providers to impose a 7% fine on any sender of remittances that is unable to provide documentation of their legal status under U.S. immigration laws. Other efforts to restrict the ability of migrants to send remittances have been passed at the state level. In 2009, Oklahoma became the first U.S. state to tax remittances.42 The Oklahoma remittance tax imposes a five-dollar minimum fee on a consumer making a wire transfer from a nondepository financial institution. For transactions of $500 or more, an additional 1% of the amount being sent is also charged. A consumer with tax liability to Oklahoma may claim a credit on their income tax return for the fees paid. Several states have considered measures nearly identical to the Oklahoma tax model including Georgia, Iowa, Kansas, Nebraska, Tennessee, Mississippi, and Texas.43

Some analysts argue, however, that restricting remittances through taxes or additional customer identification rules would not deter migration to the United States and would only drive remittances underground to informal methods of money transfer.44 In addition to increased AML/CFT risk related to informal money transfer systems, shifting remittance flows to informal channels may impede policy efforts to use remittances as a means to promote access to financial services.