Introduction

U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) has forecast U.S. coal production to decline through 2050, with the sharpest reduction to occur by the mid-2020s.1 Consequently, the coal industry's decline has contributed to economic distress in coal-dependent communities, including increased unemployment and poverty rates.2

In response, the Obama Administration launched the Partnerships for Opportunity and Workforce and Economic Revitalization (POWER) Plus Plan, which addressed the coal sector's decline through funding for (1) economic stabilization, (2) social welfare efforts, and (3) environmental efforts. The economic elements were organized within the POWER Initiative, a multi-agency federal initiative to provide economic development funding and technical assistance to address economic distress caused by the effects of energy transition principally in coal communities. Although the initiative began as a multi-agency effort as part of the POWER Plus Plan, the POWER Initiative currently operates as a funded program administered by the Appalachian Regional Commission (ARC) in its 420-county service area.

This report considers the background of the POWER Initiative and the broader effort of which it was originally a part, the POWER Plus Plan. It broadly surveys the state of POWER elements in the current administration, including elements of the initiative in the Economic Development Administration (EDA), the Appalachian Regional Commission (ARC), and funded efforts for abandoned mine land reclamation. The Appalachian Regional Commission's POWER Initiative program is the largest of these, and the only program to retain the POWER Initiative branding. This report considers its scope and activities as well as its funding history.

The POWER Initiative is supported by Congress as reflected by consistent annual appropriations. The POWER Initiative may also be of interest to Congress as an economic development program that actively facilitates and eases the repercussions of energy transition in affected communities in Appalachia. More broadly, in light of the projected continued decline of the coal industry, as well as proposals to address greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from hydrocarbon combustion, congressional interest in programs to address economic dislocations as a result of energy transition is likely to accelerate.

Background

The POWER Initiative was launched in 2015 as a multi-agency federal effort to provide grant funding and technical assistance to address economic and labor dislocations caused by the effects of energy transition—principally in coal communities around the United States.3 The POWER Initiative was a precursor to a broader effort known as the POWER Plus Plan (dubbed POWER+ by the Obama Administration).4 This latter plan was launched using preexisting funds, and was intended to develop an array of grant programs across multiple agencies to facilitate energy transition and ameliorate the negative effects of that transition. Most legislative elements of the POWER+ Plan were carried out under existing authorities rather than new legislation. Certain features continue to be active—particularly elements of the POWER Initiative within the ARC and the EDA.

The POWER+ Plan

The POWER+ Plan was organized to address three areas of concern:

- 1. economic diversification and adjustment for affected coal communities;

- 2. social welfare for coal mineworkers and their families, and the accelerated clean-up of hazardous coal abandoned mine lands; and

- 3. tax incentives to support the technological development and deployment of carbon capture, utilization, and sequestration technologies.5

The POWER+ Plan was proposed in the FY2016 President's Budget as a multi-agency approach to energy transition.6 As proposed, the POWER+ Plan involved the participation of the Department of Labor (DOL), the Appalachian Regional Commission (ARC), the Small Business Administration (SBA), the Economic Development Administration (EDA), the Department of Agriculture (USDA), the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the Department of the Treasury, the Department of Energy (DOE), the Corporation for National and Community Service, and the Department of the Interior (DOI). The FY2016 President's Budget requested approximately $56 million in POWER+ Plan grant funds: (1) $20 million for the DOL; (2) $25 million for the ARC; (3) $6 million for the EDA; and (4) $5 million for the EPA. In addition, a portion of USDA rural development funds—$12 million in grants and $85 million in loans—were aligned to POWER+ Plan priorities. Also, the plan sought $1 billion for abandoned mine land reclamation and an additional $2 billion for carbon capture and sequestration technology investments.7

The POWER Initiative

The Obama Administration described the POWER Initiative as a "down payment" on the POWER+ Plan, and focused on the Plan's economic development elements using existing funding sources (Table 1).8 Those existing funding sources (or "Targeted Funds" in Table 1) refer to funds that were set aside by the respective federal executive agency in support of the POWER+ Plan in FY2015. These funding amounts are only those funds made available initially, and do not account for additional appropriations or set-asides made available as the program progressed. The EDA was initially designated as the lead agency for the POWER Initiative, with significant funding elements from the ARC, SBA, and DOL. While led by the EDA, POWER Initiative grants were determined by the individual awarding agency. Grants were divided into two funding streams: (1) planning grants; and (2) implementation grants.

The POWER Initiative was announced in March 2015, with the first tranche of grants awarded in October 2016.9 With the exception of certain parts of the POWER Initiative and funding for reclaiming abandoned mine land (AML), broad elements of the POWER+ Plan were not enacted by Congress. Since the end of the Obama Administration, the ARC is the only federal agency with a POWER Initiative-designated program.

|

Agency |

Program / Activity |

Targeted Funds |

|

Department of Commerce, Economic Development Administration |

Assistance to Coal Communities, Economic Adjustment Assistance, and Partnership Planning |

$15 million |

|

Department of Labor, Employment and Training Administration |

Dislocated Worker National Emergency Grants |

$10-20 million |

|

Small Business Administration |

Regional Innovation Clusters and Growth Accelerators |

$3 million |

|

Appalachian Regional Commission |

Technical Assistance and Demonstration Projects |

$0.5 million |

Source: The White House, Office of the Press Secretary, "FACT SHEET: The Partnerships for Opportunity and Workforce and Economic Revitalization (POWER) Initiative," press release, March 27, 2015, https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2015/03/27/fact-sheet-partnerships-opportunity-and-workforce-and-economic-revitaliz.

Notes: The EPA, USDA, Department of the Treasury, Department of Energy, the Corporation for National and Community Service, and the Department of Interior were also noted as participating agencies, but did not initially contribute funding. Targeted funds refers to funds that were set aside by the respective federal agency in support of the POWER+ Plan in FY2015. These funding amounts are only those funds made available initially, and do not account for additional appropriations or set-asides made available as the program progressed.

POWER Elements in the Current Administration

As of November 2019, the POWER Initiative exists solely as a funded program of the ARC, and is no longer a multi-agency initiative. However, certain other elements originally included in the POWER+ Plan and the POWER Initiative continue to receive appropriations and continue to be active, but they are not designated as such by the Trump Administration.

These elements are discussed below.

The EDA Assistance to Coal Communities (ACC) Program

The EDA continues to receive appropriations for its Assistance to Coal Communities (ACC) program. The ACC program was a grant-making element launched as a part of the EDA's role in the POWER Initiative.

In FY2019,10 $30 million was designated for the ACC program as part of appropriations to the EDA.11 The FY2019 appropriations represent the fifth consecutive fiscal year of funding for the program,12 and reflect 300% growth from approximately $10 million appropriated in FY2015. However, the Trump Administration's FY2017 Budget sought to eliminate the ACC program;13 and subsequent Administration Budget requests have proposed eliminating the EDA entirely, including the ACC program.14

While the ACC is an active outgrowth of the POWER Initiative and POWER+ Plan, it is no longer associated with the POWER Initiative and instead is identified as a separate program drawing on Economic Adjustment Assistance (EAA) funds.15 Because it draws on EAA funding, ACC investments may only be used for projects located in, or substantially benefiting, a community or region that meets EDA distress criteria.

EDA economic distress is defined as

- "An unemployment rate that is, for the most recent 24-month period for which data are available, at least one percentage point greater than the national average unemployment rate;

- Per capita income that is, for the most recent period for which data are available, 80 percent or less of the national average per capita income; or

- A Special Need, as determined by EDA."16

|

FY2015 |

FY2016 |

FY2017 |

FY2018 |

FY2019 |

|

|

Funding for ACC program |

$10 |

$15 |

$30 |

$30 |

$30 |

Source: Compiled by CRS from Department of Commerce budget justification documents.

Notes: The ACC program was not identified as a specific appropriations line item until the FY2017 Department of Commerce budget justification, which sought to terminate its funding. However, that same document included past funding amounts for ACC in FY2015 and FY2016, which were included as set-asides within the EAA program. In FY2018 and FY2019, funding for the ACC program was not requested as the Trump Administration proposed terminating the EDA and its programs.

Abandoned Mine Land (AML) Reclamation Investments

One of the pillars of the POWER+ Plan was funding for the social welfare of miners and for cleanup and reclamation of former mine and other coal-related "brownfield" sites. While certain legislative proposals for these purposes were never enacted,17 Congress has approved annual funding since FY2016 for economic development grants to states for Abandoned Mine Land reclamation.18

The FY2016 appropriation of $90 million directed funds to be divided equally among the three Appalachian states with the greatest amount of unfunded AML needs (P.L. 114-13).19 The $105 million appropriated for FY2017 set aside $75 million to be divided this way, with the balance of that amount being available more broadly to other eligible AML reclamation applicants (P.L. 115-31).20 FY2018 appropriations of $115 million set aside $75 million for the three states demonstrating the greatest unmet need (P.L. 115-141).21

For FY2019, the Department of the Interior, Environment, and Related Agencies Appropriations Act, 2019, Division E of the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2019 (P.L. 116-6), appropriated $115 million, which was subdivided further: $75 million for the three Appalachian states with the greatest amount of unfunded needs; $30 million for the next three Appalachian states with the "subsequent greatest amount of unfunded needs"; and $10 million for federally recognized Indian Tribes.22

|

FY2016 |

FY2017 |

FY2018 |

FY2019 |

|

|

Appropriations for AML reclamation |

$90 |

$105 |

$115 |

$115 |

|

Amount for three Appalachian states with the greatest amount of unfunded needs |

$90 |

$75 |

$75 |

$75 |

Source: Data compiled and tabulated by CRS from: P.L. 114-13; P.L. 115-31; P.L. 115-141; and P.L. 116-6.

Notes: For FY2019, funding not reserved for the three Appalachian states with the greatest amount of unfunded AML needs was further subdivided for the first time: $75 million for the three Appalachian states with the greatest amount of unfunded needs; $30 million for the next three Appalachian states with the "subsequent greatest amount of unfunded needs"; and $10 million for grants to federally recognized Indian Tribes.

The ARC's POWER Initiative

The Appalachian Regional Commission (ARC) is the only federal agency that continues to receive regular appropriated funding for energy transition activities under the POWER Initiative designation.23 While the POWER Initiative was launched as a multi-agency effort, only the ARC chose to designate its contributions as the POWER Initiative.

About the ARC

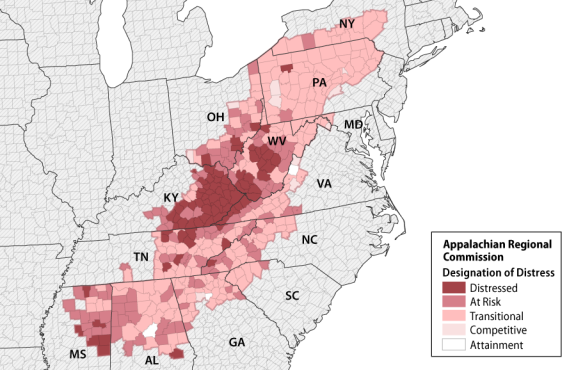

The ARC was established in 1965 to address economic distress in the Appalachian region (40 U.S.C. §14101-14704).24 The ARC's jurisdiction spans 420 counties in Alabama, Georgia, Kentucky, Ohio, New York, Maryland, Mississippi, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Tennessee, Virginia, and West Virginia (Figure 1).

The ARC is a federal-state partnership, with administrative costs shared equally by the federal government and member states, while economic development activities are federally funded through appropriations. Thirteen state governors and a federal co-chair oversee the ARC. The federal co-chair is appointed by the President with the advice and consent of the Senate.25

Scope and Activities

The ARC's POWER Initiative program prioritizes federal resources to projects and activities in coal communities that exhibit elements that

- produce multiple economic development outcomes (e.g., promoting regional economic growth; job creation; and/or employment opportunities for displaced workers);

- are specifically identified under state, local, or regional economic development plans; and

- have been collaboratively designed by state, local, and regional stakeholders.26

The ARC funds three classes of grants as part of the POWER Initiative: (1) implementation grants, with awards of up to $1.5 million; (2) technical assistance grants, with awards of up to $50,000; and (3) broadband deployment projects, with awards of up to $2.5 million.

For FY2019, $45 million in grant funding was made available, of which $15 million was reserved for broadband projects. POWER investments are subject to the ARC's grant match requirements, which are linked to the Commission's economic distress hierarchy.27

Those economic distress designations are, in descending order of distress

- distressed (80% funding allowance, 20% grant match);28

- at-risk (70%);

- transitional (50%);

- competitive (30%); and

- attainment (0% funding allowance).

Special allowances at the discretion of the commission may reduce or discharge matches, and match requirements may be met with other federal funds when allowed. Designations of county-level distress in the ARC's service area are represented in Figure 1.

POWER investments are also aligned to the ARC's strategic plan. The current strategic plan, adopted in November 2015, prioritizes five investment goals:

- 1. entrepreneurial and business development;

- 2. workforce development;

- 3. infrastructure development;

- 4. natural and cultural assets; and

- 5. leadership and community capacity.29

Given its programmatic breadth, POWER investments may link to any one of these investment goals. POWER investment determinations are made according to annual objectives outlined in the request for proposals, as well as broader investment priorities, which are building a competitive workforce; fostering entrepreneurial activities; developing industry clusters in communities; and responding to substance abuse.

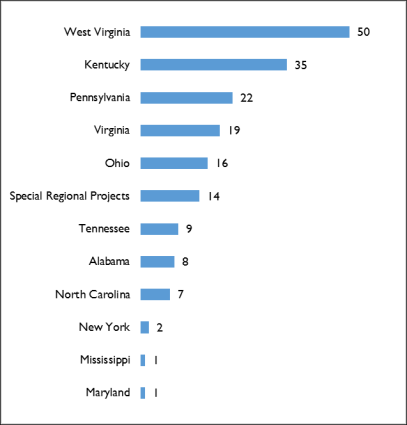

The ARC has designated $50 million annually ("activities in support of the POWER+ Plan"30) for POWER activities (Table 4). According to the ARC,31 over $148 million in investments have been made since FY2016 through 185 projects in 312 counties across the ARC's service area, leveraging an estimated $772 million of private investment. Figure 2 is a representation of the ARC's POWER Initiative projects tallied by state.

Funding History

While the POWER Initiative does not receive appropriations separate from that of the ARC as a whole, congressional intent is signaled in House Appropriations Committee reports, which specify amounts to be reserved for the POWER Initiative. In committee report language, it is described as activities "in support of the POWER+ Plan."32

Table 4 shows appropriations set aside for the POWER Initiative from FY2016 to FY2019, and for the ARC as a whole.

|

FY2016 |

FY2017 |

FY2018 |

FY2019 |

|

|

Appropriations reserved for POWER |

$50 |

$50 |

$50 |

$50 |

|

Appropriations for the ARC as a whole |

$146 |

$152 |

$155 |

$165 |

Source: Data compiled and tabulated by CRS from committee reports associated with the following appropriations bills: P.L. 114-113 (FY2016); P.L. 115-31 (FY2017); P.L. 115-141 (FY2018); P.L. 115-244 (FY2019).

The ARC received approximately $610 million in requests for POWER Initiative grant funding from FY2016 to FY2018 (Table 5). This suggests that there was unmet demand for the POWER Initiative in the Appalachian region alone (the ARC's service area, as depicted in Figure 1).

|

FY2016-FY2017 |

FY2018 |

|

|

# Applications |

216 |

231 |

|

Locally Requested Funds |

$280 million |

$329 million |

|

Awarded Funds |

$91 million |

$49 million |

Source: Data provided by the ARC and tabulated by CRS.

Notes: For FY2016 and FY2017, funding was combined into a single pot and awarded accordingly. In FY2018, funding was awarded through two competitive rounds. When this information was collected in 2019, three applications were reported to be in the final stages of review.

Policy Considerations

The Energy Information Administration projects that coal production overall will continue to decline as a consequence of falling market demand.33 In particular, the EIA forecasts coal to account for 24% of U.S. electric energy generation in 2019 and 2020, down from 28% in 2018.34 By 2050, coal is projected to decline to 17% of U.S. electricity generation, nuclear is projected to account for 12%, renewables 31%, and natural gas 39%, according to EIA projections.35

Coal's decline is a function of market forces, particularly its higher cost relative to natural gas and renewable energy options.36 In the future, under current policies, coal's cost disadvantage is expected to continue, and could be accelerated if policies are adopted to reduce GHG emissions that contribute to climate change.37 Even with federal incentives to invest in carbon capture, utilization, and storage as a means to mitigate fossil fuel-related emissions, coal may still not be competitive in many situations. As a result of falling demand, noncompetitive coal producers and their communities are expected to face continued economic dislocation.

Should it wish to broaden or intensify federal efforts to address energy transition in local communities, Congress may have several options. In the past, Congress has demonstrated bipartisan interest in the federal government providing assistance to populations adversely affected by the ongoing energy transitions. It has done so through its appropriations for the ARC's POWER Initiative, the EDA's ACC program, and the AML investments.38 In combination with evidence of unmet demand for federal assistance, as measured by unfunded requests to the ARC (Table 5), Congress may consider reviewing the balance among needs, appropriations, and effectiveness of past efforts.

Congress could conduct a review of the POWER Initiative and the efficacy of its performance and resources. This potential review suggests some particular considerations:

- Geography: While the ACC is available for the nation as a whole, the ARC's POWER Initiative is restricted to the ARC's service area in the Appalachian region. Congress may consider expanding the POWER Initiative to be available more broadly across the nation, or in a more targeted fashion as demonstrated by the ARC's program. Alternatively, funding could be made available nationwide to any eligible coal community, such as through other federal regional commissions and authorities and/or EDA regions.

- Funding: Projections of U.S. coal production (cited earlier) suggest that the ongoing transition in U.S. energy systems may lead to further localized economic distress without the development of new regional opportunities. Congress may consider the level of funding for POWER Initiative programs in the context of those economic needs. Funding levels could be tied to the overall scale of the challenge, allocated to areas with the greatest need, and made in consideration of data-driven evaluations of the program effectiveness. In assessing scale, Congress may consider macroeconomic factors as well as social and environmental policy objectives.

- Energy Type: Congress may also consider expanding the POWER Initiative program beyond the coal industry to other energy industries or regions perceived to be in decline. For example, economic strain and job losses following the closure of other electrical generating units, such as aging nuclear power plants,39 may signal additional types of displacement. EIA forecasts anticipate a modest decline in nuclear power generation by 2050 as older, less efficient reactors are retired. Nuclear-industry communities may face similar issues of economic distress and labor dislocation. Congress may also consider other public policy goals, such as reducing GHGs, to assist in promoting renewable energy types and carbon capture technologies.

Should Congress consider such efforts, the ARC's POWER Initiative program could serve as a potential model to be scaled or replicated as needed. In addition, other models have also been proposed in bills introduced in the 116th Congress that would assist coal communities in transition.40

Concluding Notes

Although the POWER+ Plan was not enacted in its entirety, some of its legacy programs continue to receive annual appropriations and remain active. The persistence of such programs suggests support among many policymakers for federal efforts to rectify, or at least attenuate, economic distress as a consequence of energy transition. In addition, were Congress to pursue policy efforts reflective of broadening concern for climate issues,41 a POWER Initiative-type program could be developed to also facilitate energy transition from fossil fuel-based energy sources to a mix of renewables and other alternatives.

Although the POWER+ Plan did not continue beyond the Obama administration, several constituent programs have continued to receive congressional backing, and applicant volume—at least in the case of the ARC's POWER Initiative—may suggest further demand for additional federal resources in addressing energy transition issues. More broadly, these mechanisms could also be purposed to facilitate federal resources for other related issues, such as related to ecological/environmental resilience and adaptation.

The POWER Initiative, as originally conceived or in its current form as a program of the ARC, has not been subjected to a formal evaluation by the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) or other research organization of its effectiveness as either a mechanism for alleviating community economic distress caused by the declining coal industry, or economic development more broadly. One recent GAO report mentioned the Assistance to Coal Communities program, but did not seek to analyze its activities or efficacy.42 Similarly, older GAO reports exist that feature the Abandoned Mine Land Reclamation program (prior to its current configuration),43 and the Appalachian Regional Commission,44 but may be of limited relevance when evaluating current programming, including more recent activities such as the POWER Initiative. Meanwhile, a number of anecdotal and media reports appear to tout the POWER Initiative's success and viability.45 The ARC, for its part, reports that the POWER Initiative has "invested over $190 million in 239 projects touching 326 counties across Appalachia." According to the ARC, those investments are "projected to create or retain more than 23,000 jobs, and leverage more than $811 million in additional private investment."46

In the ARC's 2018 Performance and Accountability Report, the ARC reported that the annual outcome target for "Students, Workers, and Leaders with Improvements" in FY2018 was exceeded by 55% "likely due to" investments from the POWER Initiative; similarly, the ARC reported the outcome target for "Communities with Enhanced Capacity" in FY2018 was exceeded by 125%, "due in part to priorities established for the POWER Initiative." The same report also noted that the ARC launched a new monitoring and evaluation effort on the POWER Initiative in September 2018 encompassing "approximately 135 POWER grants" in FY2015-FY2017.47 The results of that assessment have not yet been released.