Introduction

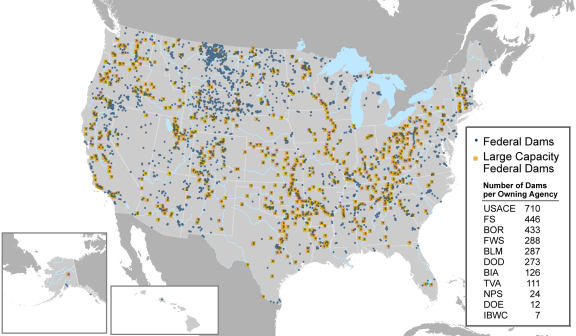

Dams may provide flood control, hydroelectric power, recreation, navigation, and water supply. Dams also entail financial costs for construction, operation and maintenance (O&M), rehabilitation (i.e., bringing a dam up to current safety standards), and repair, and they often result in environmental change (e.g., alteration of riverine habitat).1 Federal government agencies reported owning 3% of the more than 90,000 dams in the National Inventory of Dams (NID), including some of the country's largest dams (e.g., the Bureau of Reclamation's Hoover Dam in Nevada is 730 feet tall with storage capacity of over 30 million acre-feet of water).2 Most dams in the United States are owned by private entities, state or local governments, or public utilities.

Dams may pose a potential safety threat to populations living downstream of dams and populations surrounding associated reservoirs. As dams age, they can deteriorate, which also may pose a potential safety threat. The risks of dam deterioration may be amplified by lack of maintenance, misoperation, development in surrounding areas, natural hazards (e.g., weather and seismic activity), and security threats. Structural failure of dams may threaten public safety, local and regional economies, and the environment, as well as cause the loss of services provided by a dam.

In recent years, several dam safety incidents have highlighted the public safety risks posed by the failure of dams and related facilities. From 2015 to 2018, over 100 dams breached in North Carolina and South Carolina due to record flooding.3 In 2017, the near failure of Oroville Dam's spillway in California resulted in a precautionary evacuation of approximately 200,000 people and more than $1.1 billion in emergency response and repair.4 In 2018, California began to expedite inspections of dams and associated spillway structures.5

Congress has expressed an interest in dam safety over several decades, often prompted by destructive events. Dam failures in the 1970s resulting in the loss of life and billions of dollars in property damage prompted Congress and the executive branch to establish the NID, the National Dam Safety Program (NDSP), and other federal activities related to dam safety.6 Following terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001, the federal government focused on dam security and the potential for acts of terrorism at major dam sites.7 As dams age and the population density near many dams increases, attention has turned to mitigating dam failure through dam inspection programs, rehabilitation, and repair, in addition to preventing and preparing for emergencies.8

This report provides an overview of dam safety and associated activities in the United States, highlighting the federal role in dam safety. The primary federal agencies involved in these activities include the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE), and the Bureau of Reclamation (Reclamation). The report also discusses potential issues for Congress, such as the federal role for nonfederal dam safety; federal funding for dam safety programs, rehabilitation, and repair; and public awareness of dam safety risks. The report does not discuss in detail emergency response from a dam incident, dam building and removal policies, or state dam safety programs.

Safety of Dams in the United States

Dam safety generally focuses on preventing dam failure and incidents—episodes that, without intervention, likely would have resulted in dam failure. Challenges to dam safety include aging and inadequately constructed dams, frequent or severe floods (for instance, due to climate change), misoperation of dams, and dam security.9 The risks associated with dam misoperation and failure also may increase as populations and development encroach upstream and downstream of some dams.10 Safe operation and proper maintenance of dams and associated structures is fundamental for dam safety. In addition, routine inspections by dam owners and regulators determine a dam's hazard potential (see "Hazard Potential" below), condition (see "Condition Assessment" below), and possible needs for rehabilitation and repair.11

Dams by the Numbers

The NID, a database of dams in the United States, is maintained by USACE.12 For the purposes of inclusion in the NID, a dam is defined as any artificial barrier that has the ability to impound water, wastewater, or any liquid-borne material, for the purpose of storage or control of water that (1) is at least 25 feet in height with a storage capacity of more than 15 acre-feet, (2) is greater than 6 feet in height with a storage capacity of at least 50 acre-feet, or (3) poses a significant threat to human life or property should it fail (i.e., high or significant hazard dams).13 Thousands of dams do not meet these criteria; therefore, they are not included in the NID.

|

National Inventory of Dams After several dam failures in the early 1970s, Congress authorized the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) to inventory the nation's dams and tasked it with other dam safety responsibilities in P.L. 92-367. Pursuant to the act, USACE first published the National Inventory of Dams (NID) in 1975. The NID now includes over 90,000 dams. States, territories, and federal agencies self-report the information in the database; these entities collaborate closely with USACE to improve the accuracy and completeness of information, with recent emphasis on reporting emergency action plans and dam condition. Multiple bills have reauthorized appropriations for the NID; most recently, the Water Resources Development Act of 2018 (Title I of P.L. 115-270) extended the NID's annual authorization of appropriations of $500,000 through FY2023. From FY2014 to FY2019, Congress has appropriated $400,000 annually to the NID. The National Inventory of Dams (NID) can be accessed at https://nid.sec.usace.army.mil. |

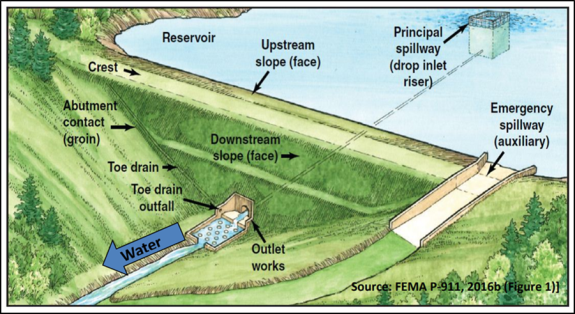

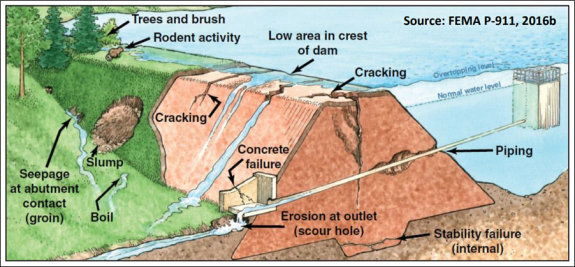

The most common type of dam is an earthen dam (see Figure 1), which is made from natural soil or rock or from mining waste materials. Other dams include concrete dams, tailings dams (i.e., dams that store mining byproducts), overflow dams (i.e., dams regulating downstream flow), and dikes (i.e., dams constructed at a low point of a reservoir of water).14 This report does not cover levees, which are manmade structures designed to control water movement along a landscape.

|

|

Source: FEMA, Pocket Safety Guide for Dams and Impoundments, 2016, at https://www.fema.gov/media-library/assets/documents/127281. Notes: Model schematic for an earthen dam. Earthen dams utilize natural materials, generally with minimum processing, and can be built with primitive equipment under conditions where any other construction material would be impracticable. Other dam types (e.g., concrete dams, tailings dams that store byproducts of mining operations) may have alternative design and structural components. |

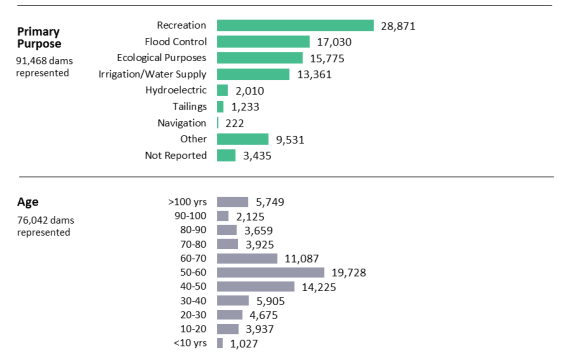

The nation's dams were constructed for various purposes: recreation, flood control, ecological (e.g., fisheries management), irrigation and water supply, hydroelectric, mining, navigation, and others (see Figure 2). Dams may serve multiple purposes. Dams were built to engineering and construction standards and regulations corresponding to the time of their construction. Over half of the dams with age reported in the NID were built over fifty years ago.15 Some dams, including older dams, may not meet current dam safety standards, which have evolved as scientific data and engineering have improved over time.16

|

|

Source: Congressional Research Service (CRS) with 2018 National Inventory of Dams (NID) data available at https://nid.sec.usace.army.mil. Notes: Some dams have multiple purposes. The "other" category may include dams used for fire protection, small farm ponds, debris control, and grade stabilization. A total of 15,426 dams in the NID had no age of construction reported. |

Dam Failures and Incidents

Dam failures and incidents—episodes that, without intervention, likely would have resulted in dam failure—may occur for various reasons. Potential causes include floods that may exceed design capacity; faulty design or construction; misoperation or inadequate operation plans; overtopping, with water spilling over the top of the dam; foundation defects, including settlement and slope instability; cracking caused by movements, including seismic activity; inadequate maintenance and upkeep; and piping, when seepage through a dam forms holes in the dam (see Figure 3).17

|

|

Source: FEMA, Pocket Safety Guide for Dams and Impoundments, 2016, at https://www.fema.gov/media-library/assets/documents/127281. Notes: The figure is of an earthen dam; other dams may have different potential modes of failure. Some potential failure modes are not illustrated, such as spillway damage and sinkholes. |

Engineers and organizations have documented dam failure in an ad hoc manner for decades.18 Some report over 1,600 dam failures resulting in approximately 3,500 casualties in the United States since the middle of the 19th century, although these numbers are difficult to confirm.19 Many failures are of spillways and small dams, which may result in limited flooding and downstream impact compared to large dam failures. Flooding that occurs when a dam is breached may not result in life safety consequences or significant property damage.20 Still, some dam failures have resulted in notable disasters in the United States.21

Between 2000 and 2019, states reported 294 failures and 537 nonfailure dam safety incidents.22 Recent events—including the evacuation of approximately 200,000 people in California in 2017 due to structural deficiencies of the spillway at Oroville Dam—have led to increased attention on the condition of dams and the federal role in dam safety.23 From 2015 to 2018, extreme storms (including Hurricane Matthew) and subsequent flooding resulted in over 100 dam breaches in North Carolina and South Carolina.24 Floods resulting from hurricanes in 2017 also filled reservoirs of dams to record levels in some regions: for example, USACE's Addicks and Barker Dams in the Houston, TX, area; the Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority's Guajataca Dam in Puerto Rico; and USACE's Herbert Hoover Dike in Florida.25 The March 2006 failure of the private Kaloko Dam in Hawaii killed seven people, and the 2003 failure of the Upper Peninsula Power Company's Silver Lake Dam in Michigan caused more than $100 million in damage.26

|

Oroville Dam, CA In 2017, failure of key components of the Oroville Dam, part of a state-owned hydropower project in California licensed by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), highlighted the risks sometimes associated with hydropower dams and raised questions about FERC's oversight of dam safety. Following higher-than-forecasted inflows from near-record precipitation, snowpack, and subsequent runoff, Oroville Dam operators opened the dam's main service spillway gates, which resulted in the spillway crumbling on one side. In addition, overtopping of the ungated auxiliary spillway (also referred to as the emergency spillway) initiated erosion of the bedrock that supports the spillway. These deficiencies prompted concerns about possible dam failure, and local emergency management officials issued an evacuation order for nearly 200,000 residents downstream of the dam. Dam operators increased water releases from the damaged main service spillway until dam water levels were safe enough to begin repairs on the spillway structures. Spillway repairs and emergency response cost an estimated $1.1 billion. At the time of the incident, FERC was reviewing the Oroville Dam project's relicensing application. In January 2018, an independent forensic team and an after-action panel raised questions about the thoroughness of the state's and FERC's oversight of the project, among other factors that may have contributed to the incident (see section on "Regulation of Hydropower Dams"). The incident also prompted a wave of new state executive and legislative actions requiring inspections of 93 spillways; emergency action plans and inundation maps for all dams posing a significant threat to human life or property; and public data release of hazard classifications, condition assessments, and inundation maps.

Sources: Independent Forensic Team Report, Oroville Dam Spillway Incident, 2018, at https://damsafety.org/ sites/default/files/files/Independent%20Forensic%20Team%20Report%20Final%2001-05-18.pdf; personal correspondence between CRS and the California Division of Safety of Dams on June 4, 2019. Notes: Overview of Oroville Dam facility prior to February 2017. |

Hazard Potential

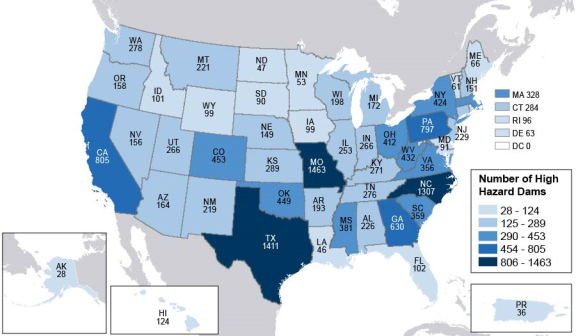

Federal guidelines set out a hazard potential rating to quantify the potential harm associated with a dam's failure or misoperation.27 As described in Table 1, the three hazard ratings (low, significant, and high) do not indicate the likelihood of failure; instead, the ratings reflect the amount and type of damage that a failure would cause. Figure 4 depicts the number of dams listed in the NID classified as high hazard in each state; 65% of dams in the NID are classified as low hazard. From 2000 to 2018, thousands of dams were reclassified increasing the number of high hazard dams from 9,921 to 15,629.28 According to FEMA, the primary factor increasing dams' hazard potential is hazard creep—development upstream and downstream of a dam, especially in the dam failure inundation zone (i.e., downstream areas that would be inundated by water from a possible dam failure).29 Reclassification from low hazard potential to high or significant hazard potential may trigger more stringent requirements by regulatory agencies, such as increased spillway capacity, structural improvements, more frequent inspections, and creating or updating an emergency action plan (EAP).30 Some of these requirements may be process and procedure based, and others may require structural changes for existing facilities.

|

Hazard Potential |

Result of Failure or Misoperation |

Number of Dams |

Percent of NID Dams |

|

High Hazard |

|

15,629 |

17% |

|

Significant Hazard |

|

11,354 |

12% |

|

Low Hazard |

|

59,679 |

65% |

|

Undetermined |

|

4,806 |

5% |

Sources: FEMA, Federal Guidelines for Dam Safety: Hazard Potential Classification System for Dams, 2004, at https://www.fema.gov/media-library-data/20130726-1516-20490-7951/fema-333.pdf; and 2018 National Inventory of Dams (NID) data available at http://nid.usace.army.mil/.

Notes: Low hazard dams are not included in the NID if they are less than 25 feet in height with a storage capacity of 15 acre-feet or less, or are 6 feet or less in height with a storage capacity of less than 50 acre-feet.

|

|

Source: CRS using 2018 National Inventory of Dams (NID) data available at http://nid.usace.army.mil/. Notes: Guam has one high hazard dam. |

Condition Assessment

The NID includes condition assessments—assessments of relative dam deficiencies determined from inspections—as reported by federal and state agencies (see Table 2).31 Of the 15,629 high hazard potential dams in the 2018 NID, 63% had satisfactory or fair condition assessment, 15% had a poor or unsatisfactory condition assessment, and 22% were not rated. For dams rated as poor and unsatisfactory, federal agencies and state regulatory agencies may take actions to reduce risk, such as reservoir drawdowns, and may convey updated risk and response procedures to stakeholders.32

|

Condition Ratings |

Description of Condition Rating |

High Hazard Dams |

Significant Hazard Dams |

Low Hazard Dams |

Undetermined Hazard |

|

Satisfactory |

|

5,202 |

2,527 |

4,789 |

7 |

|

Fair |

|

4,645 |

2,451 |

4,304 |

10 |

|

Poor |

|

2,126 |

1,435 |

3,437 |

13 |

|

Unsatisfactory |

|

258 |

119 |

323 |

2 |

|

Not Rated |

|

3,398 |

4,822 |

46,826 |

4,774 |

Source: 2018 NID data and FEMA, National Dam Safety Program.

Notes: A dam safety deficiency is an unacceptable dam condition that may affect the safety of the dam either in the near term or in the future.

Mitigating Risk

In the context of dam safety, risk is comprised of three parts:33

- the likelihood of a triggering event (e.g., flood or earthquake),

- the likelihood of a dam safety deficiency resulting in adverse structural response (e.g., dam failure or spillway damage), and

- the magnitude of consequences resulting from the adverse event (e.g., loss of life or economic damages).

Preventing dam failure involves proper location, design, and construction of structures, and regular technical inspections, O&M, and rehabilitation and repair of existing structures.34 Preparing and responding to dam safety concerns may involve community development planning, emergency preparation, and stakeholder awareness.35 Dam safety policies may address risk by focusing on preventing dam failure while preparing for the consequences if failure occurs.

Rehabilitation and Repair

Rehabilitation typically consists of bringing a dam up to current safety standards (e.g., increasing spillway capacity, installing modern gates, addressing major structural deficiencies), and repair addresses damage to a structure. Rehabilitation and repair are different from day-to-day O&M. According to a 2019 study by ASDSO, the combined total cost to rehabilitate the nonfederal and federal dams in the NID would exceed $70 billion.36 The study projected that the cost to rehabilitate high hazard potential dams in the NID would be approximately $3 billion for federal dams and $19 billion for nonfederal dams.37 Some stakeholders project that funding requirements for dam safety rehabilitation and repair will continue to grow as infrastructure ages, risk awareness progresses, and design standards evolve.38

Preparedness

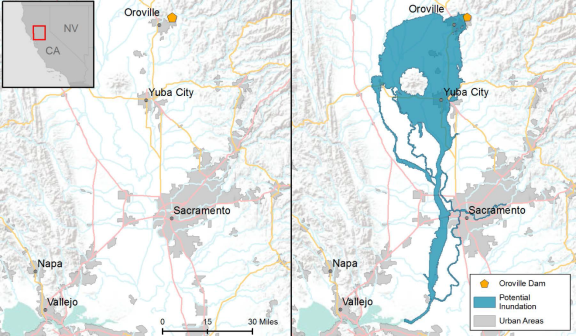

Dam safety processes and products—such as emergency action plans (EAPs) and inundation maps—may support informed decisionmaking to reduce the risk and consequences of dam failures and incidents.39 An EAP is a formal document that identifies potential emergency conditions at a dam and specifies preplanned actions to minimize property damage and loss of life.40 EAPs identify the actions and responsibilities of different parties in the event of an emergency, such as the procedures to issue early warning and notification messages to emergency management authorities. EAPs also contain inundation maps to show emergency management authorities the critical areas for action in case of an emergency (see Figure 5 for a map illustration of potential inundation areas due to a dam failure).41 Many agencies that are responsible for dam oversight require or encourage dam owners to develop EAPs and often oversee emergency response simulations (i.e., tabletop exercises) and field exercises.42 Requirements for EAPs often focus on high hazard dams. In 2018, the percentage of high hazard potential dams in the United States with EAPs was 74% for federally owned dams and 80% for state-regulated dams.43

|

Figure 5. Illustration of a Potential Inundation Map Due to Failure of Lake Oroville's Main Dam |

|

|

Source: CRS with inundation data from California Division of Safety of Dams, at https://fmds.water.ca.gov/maps/damim/. Notes: Inundation maps are based on a hypothetical failure of a dam or critical structure, and the information depicted on the maps is approximate. This scenario shows the inundation extent (with an inundation depth of at least one foot) for a failure of Lake Oroville's main dam. Failure of Lake Oroville spillways or other structures would result in alternative inundation scenarios with less extensive flooding. As required by California Water Code Section 6161, California's Division of Safety of Dams reviews and approves inundation maps prepared by licensed civil engineers and submitted by dam owners for high and significant hazard dams and their critical appurtenant structures. The Division of Safety of Dams publishes these inundation maps on a public website in static form and on a geographic information system platform. Most federal agencies do not publicly release inundation maps for federally owned dams. |

Federal agencies have developed tools to assist dam owners and regulators, along with emergency managers and communities, to prepare, monitor, and respond to dam failures and incidents.

- FEMA's RiskMAP program provides flood maps, tools to assess the risk from flooding, and planning and outreach support to communities for flood risk mitigation.44 A RiskMAP project may incorporate the potential risk of dam failure or incidents.

- FEMA's Decision Support System for Water Infrastructure Security (DSS-WISE) Lite allows states to conduct dam failure simulations and human consequence assessments.45 Using DSS-WISE Lite, FEMA conducted emergency dam-break flood simulation and inundation mapping of 36 dams in Puerto Rico during the response to Hurricane Maria in 2017.

- DamWatch is a web-based monitoring and informational tool for 11,800 nonfederal flood control dams built with assistance from the U.S. Department of Agriculture.46 When these dams experience a critical event (e.g., threatening storm systems), essential personnel are alerted via an electronic medium and can implement EAPs if necessary.

- The U.S. Geological Survey's ShakeCast is a post-earthquake awareness application that notifies responsible parties of dams about the occurrence of a potentially damaging earthquake and its potential impact at dam locations.47 The responsible parties may use the information to prioritize response, inspection, rehabilitation, and repair of potentially affected dams.

Federal Role and Resources for Dam Safety

In addition to owning dams, the federal government is involved in multiple areas of dam safety through legislative and executive actions. Following USACE's publication of the NID in 1975 as authorized by P.L. 92-367, the Interagency Committee on Dam Safety—established by President Jimmy Carter through Executive Order 12148—released safety guidelines for dams regulated by federal agencies in 1979.48 In 1996, the National Dam Safety Program Act (Section 215 of the Water Resources Development Act of 1996; P.L. 104-303) established the National Dam Safety Program, the nation's principal dam safety program, under the direction of FEMA. Congress has reauthorized the NDSP four times and enacted other dam safety programs and activities related to federal and nonfederal dams.49 A chronology of selected federal dam safety actions is provided in the box below.

|

Chronology of Selected Federal Administrative and Legislative Actions for Dam Safety

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

National Dam Safety Program

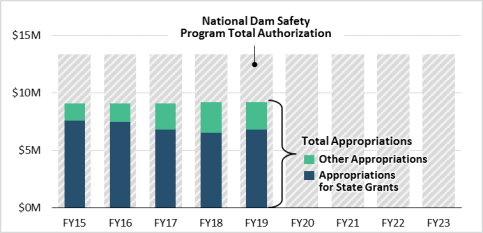

The NDSP is a federal program established to facilitate collaboration among the various federal agencies, states, and owners with responsibility for dam safety.50 The NDSP also provides dam safety information resources and training, conducts research and outreach, and supports state dam safety programs with grant assistance. The NDSP does not mandate uniform standards across dam safety programs. Figure 6 shows authorization of appropriations levels for the NDSP and appropriations for the program, including grant funding distributed to states.

|

Figure 6. Authorization Levels and Appropriations for the National Dam Safety Program |

|

|

Source: CRS with funding levels provided from personal correspondence with FEMA on July 10, 2019. Notes: Amounts are in nominal dollars. State grants are part of overall appropriations. Total annual authorization of appropriations of $13.4 million for the National Dam Safety Program includes $1 million for staff, $750,000 for training, $1.45 million for research, and $1 million for public awareness. Authorization levels and appropriations do not include High Hazard Dam Rehabilitation grants (see Figure 9). |

Advisory Bodies of the National Dam Safety Program

The National Dam Safety Review Board (NDSRB) advises FEMA's director on dam safety issues, including the allocation of grants to state dam safety programs. The board consists of five representatives appointed from federal agencies, five state dam safety officials, and one representative from the private sector.51 The Interagency Committee on Dam Safety (ICODS) serves as a forum for coordination of federal efforts to promote dam safety. ICODS is chaired by FEMA and includes representatives from the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC); the International Boundary and Water Commission; the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC); the Tennessee Valley Authority; and the Departments of Agriculture, Defense, Energy, the Interior (DOI), and Labor (DOL).52

Assistance to State Dam Safety Programs

|

Association of State Dam Safety Officials The Association of State Dam Safety Officials (ASDSO) comprises 3,000 state, federal, and local dam safety professionals and private sector experts organized to improve dam safety through research, education, and communication. After its establishment in 1983, ASDSO worked with the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) to publish the Model State Dam Safety Program to assist state officials in initiating or improving their state programs. The model outlines the key components of a dam safety program and provides guidance on the development of state programs, including legislative authorities, to minimize risks created by unsafe dams. ASDSO continues to support various elements of the National Dam Safety Program, especially through training initiatives and outreach to dam owners. The Model State Dam Safety Program may be accessed at https://damsafety.org/content/model-state-dam-safety-program-fema-316. For more information on ASDSO, see https://damsafety.org/. |

Every state (except Alabama) has established a regulatory program for dam safety, as has Puerto Rico.53 Collectively, these programs have regulatory authority for 69% of the NID dams.54 State dam safety programs typically include safety evaluations of existing dams, review of plans and specifications for dam construction and major repair work, periodic inspections of construction work on new and existing dams, reviews and approval of EAPs, and activities with local officials and dam owners for emergency preparedness.55

Funding levels and a lack of state statutory authorities may limit the activities of some state dam safety programs.56 For example, the Model State Dam Safety Program, a guideline for developing state dam safety programs, recommends one full-time employee (FTE) for every 20 dams regulated by the agency. As of 2019, one state—California—meets this target, with 75 employees and 1,246 regulated dams.57 Most state dam safety programs reportedly have from two to seven FTEs.58 In addition, some states—Alabama, Florida, Indiana, Iowa, Kentucky, Vermont, and Wyoming—do not have the authority to require dam owners of high hazard dams to develop EAPs.59

The National Dam Safety Program Act, as amended (Section 215 of the Water Resources Development Act of 1996; P.L. 104-303; 33 U.S.C. §§467f et seq.), authorizes state assistance programs under the NDSP. Two such programs are discussed below (see "FEMA High Hazard Dam Rehabilitation Grant Program" for information about FEMA's dam rehabilitation program initiated in FY2019).

Grant Assistance to State Dam Safety Programs. States working toward or meeting minimal requirements as established by the National Dam Safety Program Act are eligible for assistance grants.60 The objective of these grants is to improve state programs using the Model State Dam Safety Program as a guide. Grant assistance is allocated to state programs via a formula: one-third of funds are distributed equally among states participating in the matching grant program and two-thirds of funds are distributed in proportion to the number of state-regulated dams in the NID for each participating state.61 Grant funding may be used for training, dam inspections, dam safety awareness workshops and outreach materials, identification of dams in need of repair or removal, development and testing of EAPs, permitting activities, and improved coordination with state emergency preparedness officials. For some state dam safety programs, the grant funds support the salaries of FTEs that conduct these activities.62 This money is not available for rehabilitation and repair activities.63 In FY2019, FEMA distributed $6.8 million in dam safety program grants to 49 states and Puerto Rico (ranging from $48,000 to $465,000 per state).64

Training for State Inspectors. At the request of states, FEMA provides technical training to dam safety inspectors.65 The training program is available to all states by request, regardless of state participation in the matching grant program.

Progress of the National Dam Safety Program

At the end of each odd-numbered fiscal year, FEMA is to submit to Congress a report describing the NDSP's status, federal agencies' progress at implementing the Federal Guidelines for Dam Safety, progress achieved in dam safety by states participating in the program, and any recommendations for legislation or other actions (33 U.S.C. § 467h).66 Federal agencies and states provide FEMA with annual program performance assessments on key metrics such as inspections, rehabilitation and repair activities, EAPs, staffing, and budgets. USACE provides summaries and analysis of NID data (e.g., inspections and EAPs) to FEMA.

Some of the metrics for the dam safety program, such as the percentage of state-regulated high hazard potential dams with EAPs and condition assessments, have shown improvement. The percentage of these dams with EAPs increased from 35% in 1999 to 80% in 2018, and condition assessments of these dams increased from 41% in 2009 to 85% in 2018.67 The percentage of state-regulated high hazard potential dams inspected has remained relatively stable during the same period—between 85% to 100% dams inspected based on inspection schedules.68

Federally Owned Dams

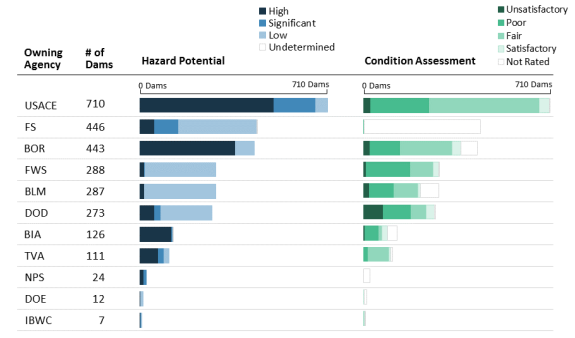

The major federal water resource management agencies, USACE and Reclamation, own 42% of federal dams, including many large dams (Figure 7).69 The remaining federal dams typically are smaller dams owned by other agencies, including land management agencies (e.g., Fish and Wildlife Service and the Forest Service), the Department of Defense, and the Bureau of Indian Affairs, among others.70 The federal government is responsible for maintaining dam safety of federally owned dams by performing maintenance, inspections, rehabilitation, and repair work. No single agency regulates all federally owned dams; rather, each federal dam is regulated according to the policies and guidance of the individual federal agency that owns the dam.71 The Federal Guidelines for Dam Safety provides basic guidance for federal agencies' dam safety programs.72

Inspections, Rehabilitation, and Repair

The Federal Guidelines for Dam Safety recommends that agencies formally inspect each dam that they own at least once every five years; however, some agencies require more frequent inspections and base the frequency of inspections on the dam's hazard potential.73 Inspections may result in an update of the dam's hazard potential and condition assessment (see Figure 8 for the status of hazard potential and condition assessments of federal dams). Inspections typically are funded through agency O&M budgets.74

After identifying dam safety deficiencies, federal agencies may undertake risk reduction measures or rehabilitation and repair activities. Agencies may not have funding available to immediately undertake all nonurgent rehabilitation and repair; rather, they generally prioritize their rehabilitation and repair investments based on various forms of assessment and schedule these activities in conjunction with the budget process.75 At some agencies, dam rehabilitation and repair needs must compete for funding with other construction projects (e.g., buildings and levees).76

|

Dam Rehabilitation and Repair on Native Lands The federal government is responsible for all dams on native lands in accordance with the Indian Dams Safety Act of 1994, as amended (P.L. 103-302; 25 U.S.C. 3801 et seq.). The Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) is in charge of 125 high or significant hazard dams listed in the NID. The BIA dams are on 43 reservations. The average age of the dams is 70 years, and one-third of the dams are classified as being in poor or unsatisfactory condition. In addition, there are over 700 additional low hazard potential or unclassified dams (not listed in the NID) on tribal lands. In April 2016, the BIA testified to the U.S. Senate Committee on Indian Affairs that $556 million was needed for deferred maintenance and repairs of BIA dams, with the backlog increasing by approximately 6% each year since 2010. Congress provided $38 million annually in FY2018 and FY2019 to the BIA for dam safety and maintenance. Low hazard dams receive less federal support and attention than high and significant hazard dams. The BIA reports that it is not aware of all low hazard dams under its jurisdiction. The Water Infrastructure Improvements for the Nation Act (WIIN Act; P.L. 114-322) established two Indian dam safety funds for the BIA to address deferred maintenance needs at eligible dams. Eligible dams are those included in the BIA Safety of Dams Program established under the Indian Dams Safety Act of 1994 that are either dams owned by the federal government and managed by the BIA or dams that have deferred maintenance documented by the BIA. Over FY2017-FY2030, the WIIN Act, as amended by America's Water Infrastructure Act of 2018 (P.L. 115-270), authorized $22.75 million per year for the High Hazard Indian Dam Safety Deferred Maintenance Fund and $10 million per year for the Low Hazard Indian Dam Safety Deferred Maintenance Fund. As of FY2019, Congress has not provided appropriations to these funds to rehabilitate eligible dams. |

Federal agencies traditionally approached dam safety through a deterministic, standards-based approach by mainly considering structural integrity to withstand maximum probable floods and maximum credible earthquakes.77 Many agencies with large dam portfolios (e.g., Reclamation and USACE) have since moved from this solely standards-based approach for their dam safety programs to a portfolio risk management approach to dam safety, including evaluating all modes of failure (e.g., seepage of water and sediment through a dam) and prioritizing rehabilitation and repair efforts.78 The following sections provide more information on specific policies at these agencies.

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

USACE implements a dam safety program consisting of inspections and risk analyses for USACE operated dams, and performs risk reduction measures or project modifications to address dam safety risks.79 USACE uses a Dam Safety Action Classification System (DSAC) based on the probability of failure and incremental risk (see Table 3).80

Congress provides funding for USACE's various dam safety activities through the Investigations, O&M, and Construction accounts.81 The Inventory of Dams line item in the Investigations account provides funding for the maintenance and publication of the NID. The O&M account provides funding for routine O&M of USACE dams and for NDSP activities, including assessments of USACE dams.

The Construction account provides funding for nonroutine dam safety activities (e.g., dam safety rehabilitation and repair modifications).82 The Dam Safety and Seepage/Stability Correction Program conducts nonroutine dam safety evaluations and studies of extremely high-risk or very high-risk dams (DSAC 1 and DSAC 2).83 Under the program, an issue evaluation study may evaluate high-risk dams, dam safety incidents, and unsatisfactory performance, and then provide determinations for modification or reclassification. If recommended, a dam safety modification study would further investigate dam deficiencies and propose alternatives to reduce risks to tolerable levels; a dam safety modification report is issued if USACE recommends a modification.84 USACE funds construction of dam safety modifications through project-specific line items in the Construction account. Modification of USACE-constructed dams for safety purposes may be cost shared with nonfederal project sponsors using two cost-sharing authorities: major rehabilitation and dam safety assurance.85 USACE schedules modifications under all of these programs based on funding availability.

Major rehabilitation is for significant, costly, one-time structural rehabilitation or major replacement work. Major rehabilitation applies to dam safety repairs associated with typical degradation of dams over time. Nonfederal sponsors are to pay the standard cost share based on authorized purposes. USACE does not provide support under major rehabilitation for facilities that were turned over to local project sponsors for O&M after they were constructed by USACE.

Dam safety assurance cost sharing may apply to all dams built by USACE, regardless of the entity performing O&M. Modifications are based on new hydrologic or seismic data or changes in state-of-the-art design or construction criteria that are deemed necessary for safety purposes. Application of the authority provided by Section 1203 of the Water Resources Development Act of 1986 (P.L. 99-662; 33 U.S.C. §467n) reduces a sponsor's responsibility to 15% of its agreed nonfederal cost share. In 2015, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) examined cost sharing for USACE dam safety repairs. GAO recommended policy clarification for the usage of the "state-of-the-art" provision and improved communication with nonfederal sponsors.86 Section 1139 of the Water Infrastructure Improvements for the Nation Act (WIIN Act; P.L. 114-322) mandated the issuance of guidance on the state-of-the-art provision, and in March 2019, USACE began to implement a new policy that allows for the state-of-the-art provision across its dam portfolio. Prior to the guidance, USACE applied the authority in January 2019 to lower the nonfederal cost share of repairing the Harland County Dam in Nebraska by approximately $2.1 million (about half of the original amount owed).87

Recent USACE dam safety construction projects have had costs ranging from $10 million to $1.8 billion; most cost in the hundreds of millions of dollars.88 In FY2018, USACE funded $268 million in work on 10 dam safety construction projects at DSAC 1 and DSAC 2 dams, and funded dam safety studies at 39 projects on DSAC 2 and DSAC 3 dams.89 In FY2019, USACE estimated a backlog of $20 billion to address DSAC 1 and DSAC 2 dam safety concerns.90

Bureau of Reclamation

Reclamation's dam safety program, authorized by Reclamation Safety of Dams Act of 1978, as amended (P.L. 95-578; 43 U.S.C. 506 et seq.), provides for inspection and repairs to qualifying projects at Reclamation dams. Reclamation conducts dam safety inspections through the Safety Evaluation of Existing Dams (SEED) program using Dam Safety Priority Ratings (DSPR; see Table 3).91 Corrective actions, if necessary, are carried out through the Initiate Safety of Dams Corrective Action (ISCA) program. With ISCA appropriations, Reclamation funds modifications on priority structures based on an evolving identification of risks and needs.

The Reclamation Safety of Dams Act Amendments of 1984 (P.L. 98-404) requires a 15% cost share from sponsors for dam safety modifications when modifications are based on new hydrologic or seismic data or changes in state-of-the-art design or construction criteria that are deemed necessary for safety purposes. In 2015, P.L. 114-113 amended the Reclamation Safety of Dams Act to increase Reclamation's authority, before needing congressional authorization to approve a modification project, from $1.25 million to $20 million.92 The act also authorized the Secretary of the Interior to develop additional project benefits, through the construction of new or supplementary works on a project in conjunction with dam safety modifications, if such additional benefits are deemed necessary and in the interests of the United States and the project. Nonfederal and federal funding participants must agree to a cost share related to the additional project benefits. 93

In FY2019, Congress appropriated $71 million for ISCA, which funded 18 dam safety modifications.94 FY2019 funding also included $20.3 million for SEED and $1.3 million for the Dam Safety Program. As of FY2019, Reclamation estimated that the current portfolio of dam safety modification projects through FY2030 would cost between $1.4 billion to $1.8 billion.95

The Commissioner of Reclamation also serves as the Department of the Interior's (DOI's) coordinator for dam safety and advises the Secretary of the Interior on program development and operation of the dam safety programs within DOI.96 In this role, Reclamation provides training to other DOI agencies with dam safety programs and responsibilities, and Reclamation's dam safety officer represents DOI on the ICODS.97

|

Dam Safety Action Classification Ratings (DSAC) |

Dam Safety Priority Ratings |

|

|

1 |

Urgent and Compelling—almost certain to fail immediately to a few years under normal operations or the combination of consequences and failure probability is extremely high. |

Immediate Priority—active failure mode or extremely high likelihood of failure requiring immediate actions to reduce risk. |

|

2 |

Urgent—likelihood of failure during normal operations or a consequence of an event is too high to assure public safety or the combination of consequences and failure probability is very high. |

Urgent Priority—potential failure modes are judged to present various serious risks, which justify urgency to reduce risk. |

|

3 |

High Priority—dam is significantly inadequate or the combination of consequences and failure probability is moderate to high. |

Moderate to High Priority—potential failure modes appear to be dam safety deficiencies that propose a significant risk of failure, and actions are needed to better define risks or to reduce risks. |

|

4 |

Priority—dam is inadequate but with low risk, such that the combination of consequences and failure probability is low. Dam may not meet all USACE engineering guidelines. |

Low to Medium Priority—potential failure modes appear to indicate a potential concern but do not indicate a pressing need for action. |

|

5 |

Normal—considered safe, meeting all agency guidelines, with tolerable residual risk. |

Low Priority—potential failure modes do not appear to present significant risk, and there are no apparent dam safety deficiencies. |

Sources: Bureau of Reclamation, Dam Safety Public Protection Guidelines: A Risk Framework to Support Dam Safety Decision-Making, 2011, at https://www.usbr.gov/ssle/damsafety/documents/PPG201108.pdf. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE), Sustainment Management System Dams Inspection Module: Department of Defense Dams Inventory and Inspection Templet, ERDC/CERL TR-18-9, 2018, at https://usace.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p266001coll1/id/7751/.

Federal Oversight of Nonfederal Dams

|

Nonfederal Dams on Federal Lands There are 5,266 nonfederal dams on federal land, with 433 rated as high hazard. Most of the dams are located on Bureau of Land Management, Forest Service, and Fish and Wildlife Service land, although several other agencies also have nonfederal dams located on their lands. Most federal agencies do not have authorities for regulating these dams, though some may have policies outlining dam safety responsibilities established through agreements. Some dams are inspected and regulated by a state government, depending on the state's authority. Federal agencies may try to work with dam owners whose dams are not regulated by federal or state agencies to carry out dam safety practices. The 2018 Department of the Interior Annual Report on Dam Safety stated that multiple bureaus have requested solicitors' opinions regarding their authorities to require private dam owners on federal lands to comply with Federal Guidelines for Dam Safety. |

Some federal agencies are involved in dam safety activities of nonfederal dams; these activities may be regulatory or consist of voluntary coordination (see box on "Nonfederal Dams on Federal Lands").

Congress has enacted legislation to regulate hydropower projects, certain mining activities, and nuclear facilities and materials.98 These largely nonfederal facilities and activities may utilize dams for certain purposes. States also may have jurisdiction or ownership over these facilities, activities, and associated dams, and therefore may oversee dam safety in coordination with applicable federal regulations.99

Regulation of Hydropower Dams

Under the Federal Power Act (16 U.S.C. §§791a-828c), FERC has the authority to issue licenses for the construction and operation of hydroelectric projects, among other things.100 Many of these projects involve dams, some of which may be owned by a state or local government. According to FERC, approximately 3,036 dams are regulated by FERC's dam safety program. Of these, 1,374 are nonfederal dams listed in the 2018 NID; 791 nonfederal dams are classified as high hazard, with 144 in California, 87 in New York, and 72 in Michigan.101 Before FERC can issue a license, FERC reviews and approves the designs and specifications of dams and other structures for the hydropower project. Each license is for a stated number of years (generally 30-50 years), and must undergo a relicensing process at the end of the license.

Along with nonfederal hydropower licensing, FERC is responsible for dam inspection during and after construction.102 FERC staff inspect regulated dams at regular intervals, and the owners of certain dams require more thorough inspections.103 According to 18 C.F.R. §12, every five years, an independent consulting engineer, approved by FERC, must inspect and evaluate projects with dams higher than 32.8 feet, or with a total storage capacity of more than 2,000 acre-feet. These inspections are to include a detailed review of the design, construction, performance, and current condition assessment of the entire project.104 Inspections are to include examinations of dam safety deficiencies, project construction and operation, and safety concerns related to natural hazards. Should an inspection identify a deficiency, FERC would require the project owner to submit a plan and schedule to remediate the deficiency.105 FERC then is to review, approve, and monitor the corrective actions until the licensees have addressed the deficiency.106 If a finding is highly critical, FERC has the authority to require risk-reduction measures immediately; these measures often include reservoir drawdowns.107

Following the spillway incident in 2017 at Oroville Dam, CA, California's Department of Water Resources engaged an independent forensic team to develop findings and opinions on the causes of the incident. FERC also convened an after-action panel to evaluate FERC's dam safety program at Oroville focusing on the original design, construction, and operations, including the five-year safety review process. Both the after-action panel and the forensic team released reports in 2018 that raised questions about the thoroughness of FERC's oversight of dam safety.108 Among other findings, the panel's report concluded that the established FERC inspection process, if properly implemented, would address most issues that could result in a failure; however, the panel's report stated that several failures occurred in the last decade because certain technical details, such as spillway components and original design, were overlooked and not addressed in the inspection or by the owner. For example, both reports highlighted inspectors' limited attention to spillways compared to more attention for main dams.109 After the Oroville incident, a FERC-led initiative to examine dam structures comparable to those at Oroville Dam identified 27 dam spillways at FERC-licensed facilities with varying degrees of safety concerns; FERC officials stated they are working with dam licensees to address the deficiencies.110

A 2018 GAO review also found that FERC had been prioritizing individual dam inspections and responses to urgent dam safety incidents, but had not conducted portfolio-wide risk analyses.111 FERC told GAO in January 2019 that it had begun developing a risk-assessment program to assess safety risks across the inventory of regulated dams and to help guide safety decisions.112 In addition, FERC produced draft guidelines in 2016 for risk-informed decisionmaking, with a similar risk management approach as USACE and Reclamation.113 FERC has allowed dam owners, generally those with a portfolio of dams, to pilot risk-informed decisionmaking using the draft guidelines for their inspections and prioritizing rehabilitation and repairs instead of using the current deterministic, standards-based approach.114

Regulation of Dams Related to Mining

At mining sites, dams may be constructed for water supply, water treatment, sediment control, or the disposal of mining byproducts and waste (i.e., tailings dams).

Under the Federal Mine Safety and Health Act of 1977, as amended (P.L. 91-173; 30 U.S.C. 801 et seq.), the Department of Labor's Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA) regulates private dams used in or resulting from mining.115 According to MSHA, approximately 1,640 dams are in its inventory. Of these, 447 are in the 2018 NID, with 220 classified as high hazard. As a regulator, MSHA develops standards and conducts reviews, inspections, and investigations to ensure mine operators comply with those standards. According to agency policies, MSHA is to inspect each surface mine and associated dams at least two times a year and each underground mine and associated dams at least four times a year.116

Under Title V of the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act of 1977, as amended (SMCRA; P.L. 95-87; 30 U.S.C. §§1251-1279), DOI's Office of Surface Mining Reclamation and Enforcement (OSMRE) administers the federal government's responsibility to regulate active coal mines to minimize environmental impacts during mining and to reclaim affected lands and waters after mining.117 OSMRE regulations require private companies to demonstrate that dams are in accordance with federal standards (30 C.F.R. §715.18). According to the 2018 DOI Annual Report on Dam Safety, OSMRE regulates 69 dams at coal mines under OSMRE's federal and Indian lands regulatory authority.118 Twenty four states have primary regulation authority (i.e., primacy) for dams under SMCRA authority: for primacy, states must meet the requirements of SMCRA and be no less effective than the federal regulations.119 If the dam is noncompliant with the approved design at any time during construction or the life of the dam's operation, OSMRE or an approved state regulatory program is to instruct the permittee to correct the deficiency immediately or cease operations.120

Regulation of Dams Related to Nuclear Facilities and Materials

The Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) was established by the Energy Reorganization Act of 1974 (42 U.S.C. 5801 et seq.) as an independent federal agency to regulate and license nuclear facilities and the use of nuclear materials as authorized by the Atomic Energy Act of 1954, as amended (P.L. 83-703).121 Among its regulatory licensing responsibilities pertaining to dams, NRC regulates uranium mill tailings dams, storage water pond dams at in situ leach (ISL) uranium recovery facilities, and dams integral to the operation of other licensed facilities that may pose a radiological safety-related hazard should they fail.122 Currently, NRC directly regulates eight dams.123 If NRC shares regulatory authority with another federal agency (e.g., FERC, USACE, Reclamation), NRC will defer regulatory oversight of the dam to the other federal agency.124 Under NRC's authority to delegate regulatory authority, states may regulate dams associated with nuclear activities based on agreements with NRC (i.e., agreement state programs).125

Federal Support for Nonfederal Dams

Nonfederal dam owners generally are responsible for investing in the safety, rehabilitation, and repair of their dams.126 In 2019, ASDSO estimated that $65.9 billion was needed to rehabilitate nonfederal dams; of that amount, $18.7 billion was needed for high hazard nonfederal dams.127 Twenty-three states provide a limited amount of assistance for these activities through a grant or low-interest revolving loan program.128 Some federal programs may specifically provide limited assistance to nonfederal dams; these programs are described below.129 In addition, more general federal programs, such as the Community Development Block Grant Program, offer broader funding opportunities for which dam rehabilitation and repair may qualify under certain criteria.130

FEMA High Hazard Dam Rehabilitation Grant Program

The WIIN Act authorized FEMA to administer a high hazard dam rehabilitation grant program, which would provide funding assistance for the repair, removal, or rehabilitation of nonfederal high hazard potential dams. Congress authorized the program to provide technical, planning, design, and construction assistance in the form of grants to nonfederal sponsors.131 Nonfederal sponsors—such as state governments or nonprofit organizations—may submit applications to FEMA on behalf of eligible dams and then distribute any grant funding received from FEMA to these dams. Eligible dams must be in a state with a dam safety program, be classified as high hazard, have developed a state-approved EAP, fail to meet the state's minimum dam safety standards, and pose an unacceptable risk to the public. Participating dams also must comply with certain federal programs and laws (e.g., flood insurance programs, the Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act), have or develop hazard mitigation and floodplain management plans, and commit to provide O&M for 50 years following completion of the rehabilitation activity.

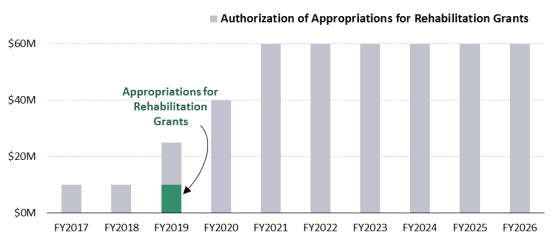

The WIIN Act authorized appropriations of $10 million annually for FY2017 and FY2018, $25 million for FY2019, $40 million for FY2020, and $60 million annually for FY2021 through FY2026 for the High Hazard Dam Rehabilitation Grant Program (see Figure 9). FEMA is to distribute grant money to nonfederal sponsors based on the following formula: one-third of the total funding is to be distributed equally among the nonfederal sponsors that applied for funds, and two-thirds of the total is to be distributed among the nonfederal sponsors proportional to the number of eligible high hazard dams represented by nonfederal sponsors. Individual grants to nonfederal sponsors are not to exceed 12.5% of total program funds or $7.5 million, whichever is less. Grant assistance must be accompanied by a nonfederal cost share of no less than 35%.

|

Figure 9. Authorization and Appropriations for FEMA's High Hazard Dam Rehabilitation Grant Program |

|

|

Source: CRS. |

Congress appropriated $10 million in FY2019 for FEMA's High Hazard Dam Rehabilitation Grant Program under the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2019 (P.L. 116-6), enacted on February 15, 2019.132 FEMA released a notice of funding opportunity on May 22, 2019, for proposals to be submitted by nonfederal sponsors by July 8, 2019.133 In FY2019, 26 nonfederal sponsors were awarded grants ranging from $153,000 to $1,250,000 to provide technical, planning, design, and construction assistance for rehabilitation of eligible high hazard potential dams.134

|

Support Through FEMA's Mitigation Programs Through programs other than those discussed above, FEMA may provide assistance to reduce the flood damage that a dam failure could cause. FEMA may provide nondisaster grants through the Preparedness Grant Program, Pre-Disaster Mitigation Program, and Flood Mitigation Assistance Program. After a presidentially declared disaster, states, territories, and tribes may pursue funding through the Hazard Mitigation Grant Program and the Public Assistance Program. For more information on qualifications and applicability for these grant programs, see FEMA, FEMA Resources and Services Applicable to Dam Risk Management, FEMA P-1068, December 2015, at https://www.fema.gov/media-library-data/1452453732996-ecaca7db5837aba46a7bbece7bc2f17e/DamRiskManagementResources.pdf. For inquiries related to FEMA's disaster mitigation programs, congressional clients may contact Diane Horn, CRS Analyst in Flood Insurance and Emergency Management. |

NRCS Small Watershed Rehabilitation Program

The Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS), within the U.S. Department of Agriculture, provides assistance for selected watershed activities generally related to managing water on or affecting agricultural or rural areas. The Watershed Protection and Flood Prevention Act (P.L. 83-566) and the Flood Control Act of 1944 (P.L. 78-534) provide the authority for NRCS to construct dams through the Watershed and Flood Prevention Operations program.135

By the end of 2019, more than half of the 11,847 watershed dams constructed with assistance from NRCS will have reached the end of their designed life spans.136 Congress created a rehabilitation program, known as the Small Watershed Rehabilitation Program, in Section 313 of the Grain Standards and Warehouse Improvement Act of 2000 (P.L. 106-472; 16 U.S.C. §1012). 137 Under this authority, watershed dams constructed with assistance from NRCS are eligible for assistance from the Small Watershed Rehabilitation Program. The rehabilitation program is intended to extend the approved service life of the dams and bring them into compliance with applicable safety and performance standards or to decommission the dams so they no longer pose a threat to life and property. From 2000 to 2018, the program authorized the rehabilitation of 288 dams.138

NRCS may provide 65% of the total rehabilitation costs; this may include up to 100% of the actual construction cost and no O&M costs.139 The Small Watershed Rehabilitation Program has discretionary funding authority of up to $85 million annually. Since FY2000, Congress has appropriated more than $700 million for rehabilitation projects. The Small Watershed Rehabilitation Program has received an average annual appropriation of $11.2 million over the last five years, including $10 million in FY2019.140

USACE Rehabilitation and Inspection Program

USACE's Rehabilitation and Inspection Program (RIP, or the P.L. 84-99 program) is used mainly for levees, but may provide federal support for selected nonfederal dams that meet certain criteria (e.g., the reservoir behind the dam has storage capacity for a 200-year flood event, otherwise referred to as a flood event having 0.5% chance of occurring in any given year).141 RIP may provide assistance for flood control works if a facility is damaged by floods, storms, or seismic activity. To be eligible for RIP assistance, damaged flood control works must be active in RIP (i.e., subject to regular inspections) and in a minimally acceptable condition at the time of damage. As of 2017, USACE considered 33 nonfederal dams as "active" in RIP.142 Because annual appropriations for USACE's Flood Control and Coastal Emergencies account are limited primarily to flood preparedness activities, USACE generally uses supplemental appropriations for major repairs through RIP.143

Issues for Congress

Congress may consider oversight and legislation relating to dam safety in the larger framework of infrastructure improvements and risk management, or as an exclusive area of interest. Congress may deliberate the federal role for dam safety, especially as most of the dams in the NID are nonfederal. Further, Congress may evaluate the level and allocation of appropriations to federal dam safety programs, project modifications for federal dams, and financial assistance for nonfederal dam safety programs and nonfederal dams. In addition, Congress may maintain or amend policies for disclosure of dam safety information when considering the federal role in both providing dam safety risk and response information to the public (including those living downstream of dams) while also maintaining security of these structures.

Federal Role

Since the 1970s, the federal government has developed and overseen national dam safety standards and has provided technical assistance for the design, construction, and O&M of dams. These activities, as well as the enhancement of federal agencies' dam safety programs, have improved certain dam safety metrics; nonetheless, deficiencies in federal and state programs may have contributed to recent incidents (e.g., the 2017 spillway incident at Oroville Dam, California).

Some federal agencies have received criticism of their dam safety programs. For example, in 2014, the Department of Defense (DOD) Inspector General found that DOD did not have a policy requiring installations to implement a dam safety inspection program consistent with the Federal Guidelines for Dam Safety.144 Since the findings, some service branches of DOD reported developing new dam safety policies including the creation of a dam safety program for the U.S. Marine Corps.145 Congress may consider other oversight activities similar to, for example, direction requiring USACE, Reclamation, and FERC to brief the Senate Committee on Appropriations on efforts to incorporate lessons learned from Oroville into dam inspection protocols across all three agencies and their state partners.146 Although incidents and reviews may result in recommending improvements to federal dam safety programs, some agencies report financial and other limitations to revising or expanding their dam safety programs.147 Congress may consider these obstacles, as identified in its oversight activities, in determining whether new authorities or appropriations are needed.

Some stakeholders argue that the federal government should continue its activities in maintaining and regulating dams owned by federal agencies and nonfederal dams under federal regulatory authority, while state dam safety programs should retain responsibility for state-regulated dams by following the guidelines of the Model State Dam Safety Program.148 However, some stakeholders, such as the Association of State Floodplain Managers and ASDSO, advocate for a larger federal role in nonfederal dam safety.149 They argue that many state dam safety programs and nonfederal dam owners have limited resources and authorities to inspect, conduct O&M, rehabilitate, and repair nonfederal dams.150 However, land use and zoning are considered nonfederal responsibilities, and some may argue against encroaching on state and local sovereignty and against the potential growth of the federal government's role.151

Dam removal is a potential policy alternative to rehabilitation and repair of high hazard dams. A dam-removal policy incentive would likely require, for example, evaluation of the current level of use of the dam, whether some or all of its functions could be economically replaced by nonstructural measures, and whether O&M, rehabilitation, and repair are feasible (e.g., the dam owner is absent or repairs are too costly).152 Congress has previously considered incentives to encourage states to remove dams deemed unnecessary or infeasible to rehabilitate. For instance, Congress authorized dam removal as an activity under FEMA's High Hazard Dam Rehabilitation Grant Program and authorized USACE to study the structural integrity and possible modification or removal for certain dams located in Vermont.153 When considering dam removal for dam safety purposes, policymakers also may weigh removal costs and the loss of recognized benefits from the dam.154

Federal Funding

Individual dam O&M, rehabilitation, and repair can range in cost from thousands to hundreds of millions of dollars.155 The responsibility for these expenses lies with dam owners; however, many nonfederal dam owners are not willing or able to fund these costs.156 As of 2019, ASDSO estimated that rehabilitation and repair of nonfederal high hazard dams in the NID would cost approximately $18.7 billion (overall rehabilitation and repair for nonfederal dams in the NID were estimated at $65.9 billion).157 Some, such as ASDSO and American Society of Civil Engineers, call for increased federal funding to rehabilitate and repair these dams.158 They note that upfront federal investment in rehabilitation and repair may prevent loss of lives and large federal outlays in emergency spending if a high hazard dam were to fail.159 Twenty-three states have created a state-funded grant or low-interest revolving loan program to assist dam owners with repairs.160 ASDSO states that the programs seem to vary significantly in the scope and reach of the financial assistance available.161 Congress authorized the "FEMA High Hazard Dam Rehabilitation Grant Program" in the WIIN Act, and subsequently provided appropriations of $10 million to the program in Division A (Department of Homeland Security Appropriations Act, 2019) of the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2019 (P.L. 116-6). For FY2020, the House Committee on Appropriations recommended no money for the grant program,162 while the Senate Committee on Appropriations recommended $10 million.163

Congress may consider the tradeoffs in focusing federal resources on federal dams versus nonfederal dams. While federal agencies report owning only 3% of dams in the NID, many of these dams are considered large dams that can affect large populations and may require costly investments in dam safety.

- In FY2019, USACE estimated a backlog of $20 billion to address DSAC 1 and DSAC 2 dam safety concerns.164 USACE has stated that investments in dam rehabilitation and repair above recent levels of appropriations would help alleviate risks and the likelihood of a major dam incident.165

- Reclamation estimates that the current portfolio of dam safety modification projects for Reclamation-owned dams would cost $1.4 billion to $1.8 billion through FY2030.166 To address this backlog, Congress has considered authorizing mandatory funding from the Reclamation Fund to provide for dam O&M, rehabilitation, and repair, so the funding would not be subject to the appropriations process.167 While some Members of Congress and stakeholders support this proposal, such as the Western States Water Council, other Members of Congress argue that increasing mandatory funding would remove congressional oversight and control of the Reclamation Fund and result in increases in spending and budget deficits, among other things.168

- Agencies with portfolios of smaller dams (e.g., Forest Service, Fish and Wildlife Service, National Park Service) report that their biggest challenge for dam safety is lack of resources, especially when dam safety is competing against other facility projects (e.g., buildings, levees).169 The Fish and Wildlife Service suggested in the FY2016-FY2017 National Dam Safety Program Report that downgrading small impoundments from the definition of a dam would alleviate some financial burdens. The agency reasoned that small impoundments that narrowly qualify as dams based on height and/or storage volume obligate the owners and regulators to perform dam safety functions with little likelihood of providing significant dam safety benefits or any genuine risk reduction.

Congress may consider continuing current spending levels for dam safety. Under current funding, some metrics for the NDSP, such as the percentage of dams with EAPs and condition assessments, have shown improvement (see "Progress of the National Dam Safety Program"). Similar metrics have improved for some federal agencies that own dams,170 and certain federal dam safety programs have implemented or are beginning to implement risk-based dam safety approaches to managing their dam portfolios (e.g., USACE and Reclamation).

Some stakeholders (e.g., a committee convened by ASDSO, the Association of State Floodplain Managers) have recommended alternative funding structures to congressional appropriations, such as a federal low interest, revolving loan program or financial credit for disaster assistance.171 For example, Congress has previously authorized a Water Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act (WIFIA) program, creating a new mechanism—credit assistance including direct loans and loan guarantees—for USACE to provide assistance for water resource projects (e.g., flood control and storm damage reduction).172 Congress may consider amending WIFIA to include making rehabilitation and repair of nonfederal dams eligible for credit assistance, or for establishing a new low-interest loan guarantee program. Although Congress authorized secured and direct loans when it enacted WIFIA in 2014, Congress has not provided appropriations to USACE to implement the programs as of FY2019. Similarly, Congress would need to provide both the authority and appropriations for these financial incentives for dam safety programs.

Risk Awareness

According to some advocacy groups, many Americans are unaware that they live downstream of a dam.173 Further, if they are aware, the public may not know if a dam is deficient, has an EAP, or could cause destruction if it failed.174 A lack of public awareness may stem from a lack of access to certain dam safety information, the public's confidence in dam integrity, or other reasons.175 Dam safety processes and products (such as inspections, EAPs, and inundation maps) are intended to support decisionmaking and enhance community resilience. Some of the information and resulting products may not be readily available to all community members and stakeholders because access to dam safety information is generally restricted from public access.176

The September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks drew attention to the security of many facilities, including the nation's water supply and water quality infrastructure, including dams. Damage or destruction of a dam by a malicious attack (e.g., terrorist attack, cyberattack) could disrupt the delivery of water resource services, threaten public health and the environment, or result in catastrophic flooding and loss of life. As a consequence of the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, current federal policy and practices restrict public access to most information related to the condition assessment of dams and consequences of dam or component failure. For example, according to USACE, dams in the NID meet the definition of critical infrastructure as defined by the Uniting and Strengthening America by Providing Appropriate Tools Required to Intercept and Obstruct Terrorism (USA PATRIOT) Act of 2001 (P.L. 107-56).177 Vulnerability assessments of critical infrastructure are restricted from public access.178 Currently USACE considers condition assessments as a type of vulnerability assessment; therefore, dam condition assessments contained in the NID are restricted only to approved government users. However, FEMA reported that following a 2017 recommendation from the NDSRB, USACE is considering making condition assessments of NID dams unrestricted for public access.179

Congress may consider reevaluating the appropriate amount of information to share (e.g., inundation scenarios from dam failure) to address public safety concerns and what amount and type of information not to share to address concerns about malicious use of that information. There are tradeoffs involved in sharing certain types of data. For example, sharing inundation mapping data with the public may raise awareness of the potential risk of living downstream of a dam, but misinterpretation of that information could cause unnecessary alarm in downstream communities.180 Currently, inundation mapping data generally are shared with emergency managers and responders rather than with the public at large.181 Some argue that disclosure to these officials is sufficient, as it provides the information to the officials who bear responsibilities for emergency response.182 In addition to managing information flow to the public to address risk, Congress might consider the risk of individuals or groups using the information for malicious purposes; namely, the concerns originally raised following the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks.