Introduction

The Group of Twenty, or G-20, is a forum for advancing international economic cooperation and coordination among 20 major advanced and emerging-market economies.1 Originally established in 1999, the G-20 rose to prominence during the global financial crisis of 2008-2009. It is now considered to be the premier forum for international economic cooperation, a position in effect held for decades following World War II by a smaller group of advanced economies (the Group of 7, or G-7).2 G-20 countries account for about 85% of global economic output, 75% of world exports, and two-thirds of the world's population.3

The G-20 leaders meet annually, and meetings among lower-level officials are held throughout the year. The G-20's focus is generally on financial and economic issues and policies, although in recent years, the G-20 has also increasingly become a forum for discussing pressing foreign policy issues. The 2017 G-20 summit was unusually contentious, with the United States at odds with other G-20 countries on trade and climate change. Japan is chairing the G-20 in 2019 and hosted the annual summit on June 28-29 in Osaka. Japan focused the agenda on trade, the digital economy, and the environment.

Congress exercises oversight over the Administration's participation in the G-20, including the policy commitments that the Administration is making in the G-20 and the policies it is encouraging other G-20 countries to pursue. Additionally, legislative action may be required to implement certain commitments made by the Administration in the G-20 process.

This report analyzes why countries coordinate economic policies and the historical origins of the G-20; how the G-20 operates; major highlights from previous G-20 summits, plus an overview of the agenda for the next G-20 summit; and debates about the U.S. role in the G-20 and its effectiveness as a forum for economic cooperation and coordination.

The Rise of the G-20 as the Premier Forum for International Economic Cooperation

Motivations for Economic Cooperation

Since World War II, governments have created and used formal international institutions and more informal forums to discuss and coordinate economic policies. As economic integration has increased over the past 30 years, however, international economic policy coordination has become even more active and significant. Globalization may bring economic benefits, but it also means that a country's economy can be affected by the economic policy decisions of other governments. These effects may not always be positive. For example, if one country devalues its currency or restricts imports in an attempt to reverse a trade deficit, another country's exports may decline. Instead of countries unilaterally implementing these "beggar-thy-neighbor" policies, some say they may be better off coordinating to refrain from such negative outcomes. Another reason countries may want to coordinate policies is that some economic policies, like fiscal stimulus, are more effective in open economies when countries implement them together.

Governments use a mix of formal international institutions and international economic forums to coordinate economic policies. Formal institutions, such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the World Bank, and the World Trade Organization (WTO), are typically formed by an official international agreement and have a permanent office with staff performing ongoing tasks.4 Governments have also relied on more informal forums for economic discussions, such as the G-7, the G-20, and the Paris Club.5 These economic forums do not have formal rules or a permanent staff.

1970s-1990s: Advanced Economies Dominate Financial Discussions

Prior to the global financial crisis of 2008-2009, international economic discussions at the top leadership level primarily took place among a small group of developed industrialized economies. Beginning in the mid-1970s, leaders from a group of five developed countries—France, Germany, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States—began to meet annually to discuss international economic challenges, including the oil shocks and the collapse of the Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates. This group, called the Group of Five, or G-5, was broadened to include Canada and Italy, and the Group of Seven, or G-7, formally superseded the G-5 in the mid-1980s. In 1998, Russia also joined, creating the G-8.6 Russia did not usually participate in discussions on international economic policy, which continued to occur mainly at the G-7 level. Meetings among finance ministers and central bank governors typically preceded the summit meetings. Macroeconomic policies discussed in the G-7 context included exchange rates, balance of payments, globalization, trade, and economic relations with developing countries. Over time, the G-7's, and subsequently the G-8's, focus on macroeconomic policy coordination expanded to include a variety of other global and transnational issues, such as the environment, crime, drugs, AIDS, and terrorism.

1990s-2008: Emerging Economies Gain Greater Influence

Although emerging economies became more active in the international economy, particularly in financial markets, starting in the early 1990s, this was not reflected in the international financial architecture until the Asian financial crisis in 1997-1998. The Asian financial crisis demonstrated that problems in the financial markets of emerging-market countries can have serious spillover effects on financial markets in developed countries, making emerging markets too important to exclude from discussions on economic and financial issues. The G-20 was established in late 1999 as a permanent international economic forum for encouraging coordination between advanced and emerging economies. However, the G-20 was a secondary forum to the G-7 and G-8; the G-20 convened finance ministers and central bank governors, while the G-8 also convened meetings among leaders, in addition to finance ministers.

Emerging markets were also granted more sway in international economic discussions when the G-8 partly opened its door to them in 2005.7 The United Kingdom's Prime Minister Tony Blair invited five emerging economies—China, Brazil, India, Mexico, and South Africa—to participate in G-8 discussions but not as full participants (the "G-8 +5"). The presence of emerging-market countries gave them some input in the meetings but they were clearly not treated as full G-8 members. Brazil's finance minister is reported to have complained that developing nations were invited to G-8 meetings "only to take part in the coffee breaks."8

2008-Present: Emerging Economies Get a Seat at the Table

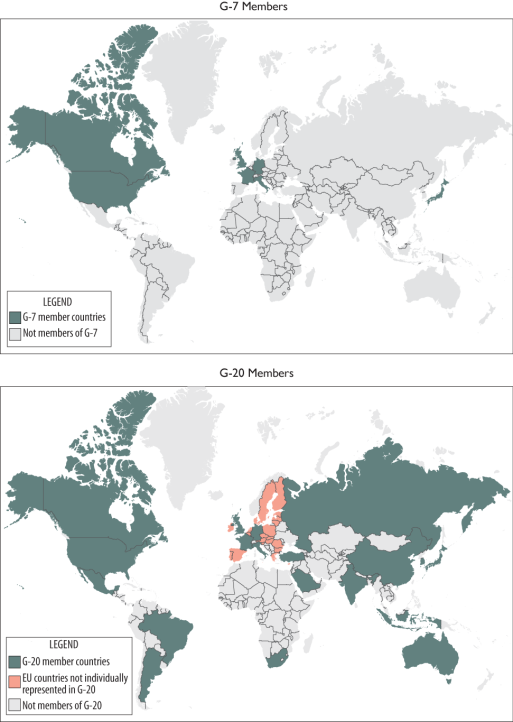

It is only with the outbreak of the global financial crisis in fall 2008 that emerging markets have been invited as full participants to international economic discussions at the highest (leader) level (Figure 1). There are different explanations for why the shift from the G-7 to the G-20 occurred. Some emphasize recognition by the leaders of developed countries that emerging markets have become sizable players in the international economy and are simply "too important to bar from the room."9

Others suggest that the transition from the G-7 to the G-20 was driven by the negotiating strategies of European and U.S. leaders. It is reported that France's president, Nicolas Sarkozy, and Britain's prime minister, Gordon Brown, pushed for a G-20 summit, rather than a G-8 summit, to discuss the economic crisis in order to dilute perceived U.S. dominance over the forum, as well as to "show up America and strut their stuff on the international stage."10 Likewise, it is reported that President George W. Bush also preferred a G-20 summit in order to balance the strong European presence in the G-8 meetings.11 Some attribute the G-20's staying power to the political difficulties of reverting back to the G-7 after having convened the G-20 leaders.

|

|

Source: G-20 website, http://www.g20.org. Notes: The European Union (EU) is a member of the G-20. |

How the G-20 Operates

Frequency of Meetings

The G-20 meetings among heads of state, or "summits," are the focal points of the G-20 discussions. Starting in 2011, the G-20 leaders began convening annually, although various lower-level officials meet frequently before the summits to begin negotiations and after the summits to discuss the logistical and technical details of implementing the agreements announced at the summits. Specifically, the G-20 finance ministers and central bank governors meet several times a year, and other ministers may also be called to meet at the request of the G-20 leaders. In addition, there are meetings among the leaders' personal representatives, known as "sherpas."12

Overall, the G-20 process has led to the creation of a complex set of interactions among many different levels of G-20 government officials. Some argue that the high frequency of interactions is conducive to forming open communication channels, while others argue that the G-20 process has created undue administrative burden on the national agencies tasked with implanting and managing their countries' participation in the G-20 process.

U.S. Representation

Within the U.S. government, the Department of the Treasury is the lead agency in coordinating U.S. participation in the G-20 process. However, the G-20 works on a variety of issues, and the Department of the Treasury works closely with other U.S. agencies in the G-20 process, including the Federal Reserve, the State Department, the U.S. Agency for International Development, and the Department of Energy. The White House, particularly through the National Security Council and the U.S. Trade Representative, is also heavily involved in the G-20 planning process.

Location of Meetings and Attendees

Unlike formal international institutions, such as the United Nations and the World Bank, the G-20 does not have a permanent headquarters or staff. Instead, each year, a G-20 member country serves as the chair of the G-20. The chair hosts many of the meetings, and is able to shape the year's focus or agenda. The chair also establishes a temporary office that is responsible for the group's secretarial, clerical, and administrative affairs, known as the temporary "secretariat." The secretariat also coordinates the G-20's various meetings for the duration of its term as chair and typically posts details of the G-20's meetings and work program on the G-20's website.13

The chair rotates among members and is selected from a different region each year. Table 1 lists the G-20 chairs since 1999, as well as the countries scheduled to chair the G-20 through 2022. The United States has never officially chaired the G-20, although the United States did host G-20 summits in 2008 and 2009 during the height of the global financial crisis.

|

Year |

Country |

Year |

Country |

|

|

1999-2001 |

Canada |

2012 |

Mexico |

|

|

2002 |

India |

2013 |

Russia |

|

|

2003 |

Mexico |

2014 |

Australia |

|

|

2004 |

Germany |

2015 |

Turkey |

|

|

2005 |

China |

2016 |

China |

|

|

2006 |

Australia |

2017 |

Germany |

|

|

2007 |

South Africa |

2018 |

Argentina |

|

|

2008 |

Brazil |

2019 |

Japan |

|

|

2009 |

United Kingdom |

2020 |

Saudi Arabia |

|

|

2010 |

South Korea |

2021 |

Italy |

|

|

2011 |

France |

2022 |

India |

Source: G-20 website, http://www.g20.org.

In addition to the G-20 members, some countries attended the G-20 summits at the invitation of the country chairing the G-20. In 2010, the G-20 formalized the participation of five non-G-20 members at the leaders' summit, of which at least two would be African countries.14 In 2019, leaders from eight countries outside the G-20 participated, from Chile, Egypt, the Netherlands, Senegal, Singapore, Spain, Thailand, and Vietnam. Several regional organizations and international organizations also attend G-20 summits. For example, official participants typically have included representatives from the European Commission; the European Council; the International Labour Organization (ILO); the International Monetary Fund (IMF); the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD); the United Nations (U.N.); the World Bank; and the World Trade Organization (WTO).

Agreements

All agreements, comments, recommendations, and policy reforms reached by the G-20 finance ministers, central bankers, and leaders are done so by consensus. There is no formal voting system as in some formal international economic institutions, like the IMF. Participation in the G-20 meetings is restricted to members and invited participants and is not open to the public. After each meeting, however, the G-20 publishes online the agreements reached among members, typically as communiqués or declarations.15 The G-20 does not have a way to enforce implementation of the agreements reached by the G-20 at the national level beyond moral suasion; the G-20 has no formal enforcement mechanism and the commitments are nonbinding. This contrasts with the World Trade Organization (WTO), for example, which does have formal enforcement mechanisms in place.

G-20 Summits

The G-20 summits are the key meetings where major G-20 policy commitments are typically announced. G-20 policy announcements and commitments are nonbinding, and the record of implementing these commitments is wide ranging. The types of commitments or agreements reached at the G-20 summits have evolved as global economic conditions have changed, from the pressing height of the global financial crisis, to signs of recovery amid high unemployment in some advanced economies, to concerns about the Eurozone crisis. In addition, as the pressing nature of the global financial crisis has abated, the scope of issues covered by the G-20 has expanded to other issues, such as development and the environment. Under President Donald Trump, who campaigned on an "America First" platform, the United States has been at odds with many G-20 countries on trade and climate change, and discussions at time have reportedly been contentious. Some policy analysts have referred to the forum as the "G19+1," signifying these divisions.16 Table A-1 presents information about major highlights from the summits held to date.

Examples of major G-20 initiatives include coordination of fiscal policies during the global financial crisis, a tripling of IMF resources, and strengthening the Financial Stability Board (FSB) to coordinate and monitor international progress on regulatory reforms, among others. Progress on other G-20 commitments has been much slower, such as correcting global imbalances, concluding the WTO Doha Round of multilateral trade negotiations, and eliminating fossil fuel subsidies. Tracking progress on G-20 commitments can be complicated, as subsequent summits may extend the timelines for completing policy reforms, reiterate previous commitments, or drop discussion of prior policy pledges.

Previous G-20 summits have typically attracted protesters from a broad mix of movements, including environmentalists, trade unions, socialist organizations, faith-based groups, antiwar camps, and anarchists.17 At the 2009 summit in Pittsburgh, for example, thousands of protestors gathered in the streets, holding signs with slogans such as "We Say No To Corporate Greed" and "G20=Death By Capitalism."18 Likewise, the 2017 summit in Hamburg attracted thousands of protestors. Protests turned violent, with more than 100 police officers injured and 45 protestors jailed.19 Not all G-20 summits are marked by large-scale demonstrations. For example, the 2014 summit in Australia and the 2016 summit in China were relatively quiet, which may be related to the distance required to travel to Australia and the tight control on protests in China.20

The 2019 Summit in Osaka, Japan

Japan holds the rotating chair of the G-20 in 2019, and focused the summit agenda on three major issues: free and fair trade, the digital economy, and tackling environmental challenges. Discussions also focused on a range of other issues, including infrastructure investment, global finance, anti-corruption, employment, women's empowerment, agriculture, development, global health, and migration, with varying consequence and degree of specificity.

Discussions on trade and climate change were reportedly the most contentious, although consensus was reached on language to include in the joint communiqué.21 In particular, leaders agreed to general principles supporting trade (free, fair, non-discriminatory, transparent, predictable, and stable) and pledged to reform the World Trade Organization (WTO), which was also pledged during the 2018 summit in Buenos Aires. The leaders did not repeat previous pledges to fight protectionism, reflecting, at least in part, current divisions over U.S. tariff policy and retaliatory measures by other countries.

On climate change, the communiqué reflected again the split between the United States, which has decided to withdraw from the Paris Agreement, and the other countries (the "G-19"), which continues to support and implement the Paris Agreement. It is unusual for communiqués to state so clearly dissenting views among participating countries. Reportedly, French President Emmanuel Macron pushed the language supporting the Paris Agreement, and prevented some countries from waffling on their prior commitments.22

Divisions also arose over data governance. Japan had pushed an effort to allow the international "free flow of data under rules we can all count upon" and was seeking to launch a side agreement titled the "Osaka Track" that would prepare rules for the digital economy.23 However, it faced considerable opposition, with India, Indonesia, and South Africa opting out of the standalone agreement on data governance.24

In terms of major deliverables from the summit, the leaders' endorsement of the "G20 Principles for Quality Infrastructure Investment" was considered notable by some analysts. Japan has championed high standards for infrastructure investment, and China, whose infrastructure investment practices have been criticized, was also a signatory to the agreement. Some analysts have argued that the most consequential outcomes were reached in sideline meetings, including the U.S.-China agreement to resume trade talks, news that the EU and Mercosur struck a trade agreement, and agreement between Russia and Saudi Arabia to extent their oil production agreement.25

Saudi Arabia Scheduled to Chair in 2020

Saudi Arabia is scheduled to chair the G-20 in 2020, and plans to host the summit in Riyadh on November 21-22. Meetings among lower level officials would be held in Saudi Arabia throughout the year. A United Nations expert who investigated the murder of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi has called on world powers to reconsidering holding the next G-20 summit in Saudi Arabia,26 although that proposal has not gained much traction.27 It is unclear what issues Saudi Arabia would prioritize as the G-20 chair, but some experts have "low expectations" for climate change and women's empowerment, which have become more prominent issues at the G-20 in recent years.28

Debate About the G-20

The United States has traditionally been a leader at the G-20 summits, and as noted earlier was instrumental in convening the first leader-level meetings in 2008. Under the Trump Administration, the United States has been at odds with the other countries, and reportedly found it difficult to reach consensus on G-20 commitments. U.S. participation in the G-20 has contributed to ongoing debate about the U.S. leadership in the world under the Trump Administration.29 Some commentators are concerned that the United States is isolated at the G-20, reflecting a growing trend of abdication of U.S. leadership and abandonment of U.S. allies.30 Others are more optimistic, arguing that differences between the United States and other countries are overblown and that President Trump is pursuing foreign policies consistent with his campaign pledges. Trump Administration officials have argued that the summit helped strengthen alliances around the world and demonstrated a resurgence of American leadership to bolster common interests, affirm shared values, confront mutual threats, and achieve renewed prosperity.31

Recent summits have also raised questions about the G-20's usefulness. Some argue it is a vital forum for a diverse set of countries to discuss their differences. Others wonder whether the G-20, which initially brought together leaders to coordinate the response to the global financial crisis of 2008-2009, has become less consequential over time. Recently one analyst argued that the G-20 has struggled to "cope with the challenges represented by China's state capitalism and U.S. unilateralism."32 Three broad scenarios for the future of the G-20 have been discussed. Specifically, the G-20 as a coordinating forum will be (1) effective; (2) ineffective; or (3) effective in some instances but not others. These possible scenarios are discussed in greater detail below.

Scenario 1: Effective

Some believe that the G-20 is an effective forum for international economic cooperation. The G-20 is able to play this role, it is argued, for three reasons. First, the G-20 includes all the major economic players at the table, but at the same time is small enough to facilitate concrete negotiations. Second, the involvement of national heads of state in the negotiations could serve to facilitate commitments in major policy areas. Third, as the issues discussed by the G-20 leaders expand, the G-20 may be able to facilitate cooperation by enabling trade-offs among major concerns, such as climate change and trade, that are not possible in issue-specific forums and institutions.

G-20 optimists typically point to the G-20's successes at the height of the financial crisis, when the G-20 played a unique, strong, and central role in steering the recovery efforts. The G-20 was the source of major decisions regarding fiscal stimulus, regulatory reform, tripling the IMF's lending capacity, and other response efforts. The G-20 also tasked other international organizations, such as the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), the IMF, the World Bank, and the Financial Stability Board (FSB), with facilitating, monitoring, or implementing various aspects of the response to the crisis. Finally, G-20 proponents argue that, even if agreement on policies is not always reached, it is a critical forum for discussing major policy initiatives across major countries and encouraging greater cooperation.

Scenario 2: Ineffective

Others are skeptical that the G-20 is an effective forum for international cooperation post-financial crisis, for at least four reasons. First, the G-20 includes a diverse set of countries with different political and economic philosophies. As economic recovery becomes more secure, it is argued that this heterogeneous group with divergent interests will have trouble reaching agreements on global economic issues. Some argue that the G-20 failed to provide adequate leadership in responding to the Eurozone crisis, helping forge a conclusion to the Doha negotiations, and deter unilateral trade actions by member countries.

Second, some believe the G-20 does not include the right mix of countries. It is argued that Europeans are overrepresented at the G-20 (with Germany, France, Italy, the United Kingdom, and the European Union accounting for 5 of the 20 slots), while some important emerging-market countries are excluded. Poland, Thailand, and Egypt have been cited as examples (see Appendix B).33 By concentrating European interests while excluding important emerging markets from the negotiating table, it will be difficult, it is argued, to achieve cooperation on economic issues of global scope.

Third, some experts believe that the G-20 will be ineffective because it has no enforcement mechanism beyond "naming and shaming" and with little follow-up will not be able to enforce its commitments. As evidence that the G-20 is an ineffective steering body in the international economy, G-20 skeptics point to the portions of recent G-20 declarations that merely reiterate commitments made by countries in other venues and institutions or at previous G-20 summits. Likewise, some of the declarations identify areas that merit further attention or study, without including concrete policy commitments.

Fourth, some argue that the G-20's effectiveness since the crisis has diminished because the issues covered by the G-20 have broadened, but there is now little follow-through from one summit to the next. For example, a major deliverable from the Toronto summit in June 2010 was targets for fiscal consolidation among advanced economies. However, these targets received little attention in the subsequent G-20 summit in Seoul in November 2010, where the focus shifted to development, among other issues. Likewise, France's focus for the November 2011 summit was on reform of the international monetary system, but it is not clear how much attention was focused on that issue at subsequent summits.

Scenario 3: Effective in Some Instances, but Not Others

A third scenario represents a middle ground between the previous two, namely, that the G-20 will be effective in some instances but not others. It is argued the G-20 could be an effective body in times of economic crisis, when countries view cooperation as critical, but less effective when the economy is strong and the need for cooperation feels less pressing. Proponents of this view point to the strong commitments achieved during the height of the crisis compared to what many view as the weaker outcomes of subsequent summits, when financial markets were more stable.

Another variant is that the G-20 will prove effective in facilitating cooperation over some issue areas but not others. For example, the G-20 could be effective in coordinating monetary policy across the G-20 countries, by providing a formal structure for finance ministers, central bankers, and leaders to gather and discuss monetary policy issues. In most countries, central banks exercise largely autonomous control over monetary policy issues and would have the authority to implement decisions reached in G-20 discussions. Likewise, the G-20 may be effective at tasking other international organizations, such as the IMF and the FSB, with various functions to perform or reports to write. By contrast, it is argued that the G-20 could find coordination of other policies more difficult. One example may be fiscal policies, because although finance ministers and national leaders undoubtedly can influence fiscal policies at the national level, control over fiscal policies in many countries ultimately lies with national legislatures. It is not clear to what extent national legislatures will feel bound in their policymaking process by decisions reached at the G-20 and thus how effective G-20 coordination on these issues will be.

Appendix A. G-20 Summits: Context and Major Highlights

|

Date |

Location |

Major Highlights (Selected) |

|

|

1. |

November 2008 |

Washington, DC, United States |

|

|

2. |

April 2009 |

London, UK |

|

|

3. |

September 2009 |

Pittsburgh, United States |

|

|

4. |

June 2010 |

Toronto, Canada |

|

|

5. |

November 2010 |

Seoul, South Korea |

|

|

6. |

November 2011 |

Cannes, France |

|

|

7. |

June 2012 |

Los Cabos, Mexico |

|

|

8. |

September 2013 |

St. Petersburg, Russia |

|

|

9. |

November 2014 |

Brisbane, Australia |

|

|

10. |

November 2015 |

Antalya, Turkey |

|

|

11. |

July 2016 |

Hangzhou, China |

|

|

12. |

July 2017 |

Hamburg, Germany |

|

|

13. |

Nov/Dec 2018 |

Buenos Aires, Argentina |

|

|

14. |

June 2019 |

Osaka, Japan |

|

Source: G-20 website, http://www.g20.org; CRS analysis.

Notes: For summit documents (leader statements and declarations), see http://www.g20.utoronto.ca/summits/index.html.

Appendix B. World's Largest Countries and Entities

Table B-1. World's Largest Countries and Entities

(Forecasted 2019 GDP in current prices, in billions of U.S. dollars)

|

Rank |

G-20 Member |

Non G-20 Member |

GDP |

Rank |

G-20 Member |

Non G-20 Member |

GDP |

|

|

1. |

United States |

21,345 |

21. |

Turkey |

706 |

|||

|

2. |

European Union |

17,963 |

22. |

Taiwan |

601 |

|||

|

3 |

China |

14,217 |

23. |

Poland |

593 |

|||

|

4. |

Japan |

5,176 |

24. |

Sweden |

547 |

|||

|

5. |

Germany |

3,964 |

25. |

Belgium |

532 |

|||

|

6. |

India |

2,972 |

26. |

Thailand |

517 |

|||

|

7. |

United Kingdom |

2,829 |

27. |

Iran |

485 |

|||

|

8. |

France |

2,762 |

28. |

Argentina |

478 |

|||

|

9. |

Italy |

2,026 |

29. |

Austria |

460 |

|||

|

10. |

Brazil |

1,960 |

30. |

Nigeria |

445 |

|||

|

11. |

Canada |

1,739 |

31. |

UAE |

428 |

|||

|

12. |

South Korea |

1,657 |

32. |

Norway |

427 |

|||

|

13. |

Russia |

1,610 |

33. |

Hong Kong |

382 |

|||

|

14. |

Spain |

1,429 |

34. |

Ireland |

382 |

|||

|

15. |

Australia |

1,417 |

35. |

Israel |

382 |

|||

|

16. |

Mexico |

1,241 |

36. |

Malaysia |

373 |

|||

|

17. |

Indonesia |

1,101 |

37. |

Singapore |

373 |

|||

|

18. |

Netherlands |

914 |

38. |

South Africa |

371 |

|||

|

19. |

Saudi Arabia |

762 |

39. |

Philippines |

357 |

|||

|

20. |

Switzerland |

708 |

40. |

Denmark |

350 |

Source: International Monetary Fund (IMF), World Economic Outlook, April 2019.

Notes: The European Union (EU) includes 28 countries. Ranking is for illustrative purposes only. Using a different measure of economic size, such as GDP adjusted for differences in prices levels across countries (GDP adjusted for purchasing power parity), could produce a different ranking.