When Congress enacted the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) in 2010, it required employment-based health plans and health insurance issuers to cover certain preventive health services without cost sharing.1 Those services, because of agency guidelines and rules, would soon include contraception for women.2 The federal contraceptive coverage requirement—sometimes called the "contraceptive mandate"3—has generated significant public policy and legal debates. Proponents of the requirement have stressed a need to make contraception more widely accessible and affordable to promote women's health and equality.4 Opponents have centrally raised religious freedom–based objections to paying for or otherwise having a role in the provision of coverage for some or all forms of contraception.5 The Supreme Court first took up a challenge to the contraceptive coverage requirement in 2014 in Burwell v. Hobby Lobby Stores, Inc.6 In Hobby Lobby, the Court held that the requirement did not properly accommodate the religious objections of closely held corporations.7

Since Hobby Lobby, legal challenges to the contraceptive coverage requirement have continued, leaving the scope and enforceability of the requirement in an uncertain legal posture. The lower federal courts divided over the legality of an accommodation process instituted in 2013 that shifted the responsibility to provide coverage from an objecting employer to its insurer once the employer certified its religious objections.8 In 2017, citing the uncertain legal footing of that accommodation, the Trump Administration decided to automatically exempt most nongovernmental entities from the coverage requirement based on their religious or moral objections.9 However, more than 15 states filed or joined lawsuits challenging the expanded exemptions.10 Federal courts have preliminarily enjoined the government from implementing the expanded exemptions while those challenges proceed.11 At the same time, the government is largely precluded from relying on the prior accommodation process as a result of a nationwide injunction issued by a federal district court.12

This report begins by explaining the statutory and regulatory framework for the federal contraceptive coverage requirement. It then recaps the Supreme Court's decision in Hobby Lobby before discussing the agency actions taken in response to that decision and subsequent Supreme Court rulings and executive action. Next, the report discusses court cases involving challenges to the coverage exemptions and accommodations, including cases pending in federal district or appellate courts in the First, Third, Fifth, and Ninth judicial circuits.13 The report concludes with some considerations for Congress, including broadly identifying legal options for clarifying the scope of the contraceptive coverage requirement.

The Contraceptive Coverage Requirement

The federal contraceptive coverage requirement stems from the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act but was developed and modified by subsequent agency guidelines and rules.14 Before the ACA, various federal and state requirements dictated whether a health plan needed to cover contraceptive services.15 Although more than half of the states required plans covering prescription drugs to include contraception,16 access was typically subject to cost-sharing requirements.17 The scope of religious exemptions from these state requirements varied.18 Moreover, each state's law extended "only to insurance plans that [were] sold to employers and individuals in [that] state."19 It did not apply to self-insured employer-sponsored health plans (also known as self-funded plans) in which nearly 60% of covered workers were enrolled.20 Self-insured plans are governed by the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 (ERISA),21 a federal law that generally did not require coverage for specific preventive services before the ACA.22 Nevertheless, whether as a matter of law or industry practice, "most private insurance and federally funded insurance programs" offered some form of insurance coverage for contraception before the federal contraceptive coverage requirement.23

With the enactment of the ACA, Congress required certain employment-based health plans and health insurance issuers (insurers)24 to cover various preventive health services without cost sharing.25 One ACA provision specifically requires coverage "with respect to women" for "preventive care and screenings . . . as provided for in comprehensive guidelines supported by the Health Resources and Services Administration [(HRSA)]" within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS).26 To implement this requirement, HHS commissioned a study by the Institute of Medicine (IOM)27 "to review what preventive services are necessary for women's health and well-being."28 In its final report, the IOM recommended that HRSA consider including the "full range of Food and Drug Administration [(FDA)]-approved contraceptive methods, sterilization procedures, and patient education and counseling for women with reproductive capacity."29 Among other reasons, IOM concluded that "[s]ystematic evidence reviews and other peer-reviewed studies provide evidence that contraception and contraceptive counseling are effective at reducing unintended pregnancies," which HHS had identified as a specific national health goal.30 HRSA adopted the IOM's recommendation, including in HRSA's 2011 Women's Preventive Services Guidelines (HRSA guidelines) "all" FDA-approved contraception31 "as prescribed."32

The HRSA guidelines applied to plan years beginning on or after August 1, 2012.33 However, they exempted certain "religious employers"—houses of worship and certain related entities that primarily employed and served persons who shared their religious tenets.34 In 2012, HHS announced a temporary "safe harbor" from government enforcement of the coverage requirement for certain nonexempt, nonprofit organizations with religious objections to covering some or all forms of contraception.35 Subsequent rules called such nonprofits "eligible organizations."36

On July 2, 2013, following a notice and comment period, HHS, the Department of Labor (DOL), and the Department of the Treasury (the Departments)37 jointly issued a final rule (2013 Rule) to "simplify and clarify the religious employer exemption" and "establish accommodations" for eligible organizations.38 The rule continued to authorize HRSA to provide an automatic exemption to the coverage requirement for houses of worship.39 However, it no longer required those employers to have "the inculcation of religious values" as their purpose or to "primarily" employ and serve "persons who share [their] religious tenets" to qualify for the exemption.40

The 2013 Rule also established an accommodation process for "eligible organizations"41—essentially, nonprofit, religious organizations with religious objections to some or all forms of contraception.42 The accommodation also extended to student health plans arranged by eligible institutions of higher education.43 Eligible organizations could comply with the contraceptive coverage requirement by completing a self-certification form provided by HHS and DOL and sending copies of this form to their insurers or third-party administrators (TPAs), as applicable.44 For insured plans, the rule required the issuers, upon receipt of a certification, to "[e]xpressly exclude contraceptive coverage" (or the subset of objected-to methods) from the applicable plans but separately pay for any required, excluded contraceptive services for the enrolled individuals and their beneficiaries.45 For self-insured plans, the rule stated that the TPA, upon receipt of a certification, would become the "plan administrator" for contraceptive benefits under ERISA and responsible for providing contraceptive coverage.46 In addition, the certification provided to the TPA would become "an instrument under which the plan is operated."47 The rule required the insurer or TPA, rather than the objecting organization, to notify plan participants that separate payments would be made for contraception and that the organization would not be administering or funding such coverage.48

RFRA and the Hobby Lobby Decision

Numerous organizations filed lawsuits challenging the contraceptive coverage requirement and the accommodation process.49 Among other claims, these plaintiffs argued that the requirement violated the Religious Freedom Restoration Act of 1993 (RFRA).50 RFRA is a federal statute enacted in response to Employment Division v. Smith,51 a 1990 Supreme Court decision holding that the Free Exercise Clause of the First Amendment does not require the government to exempt religious objectors from generally applicable laws.52 Except under narrow circumstances, RFRA prohibits the federal government from "substantially burden[ing] a person's exercise of religion even if the burden results from a rule of general applicability."53 RFRA allows such a burden only if the government shows that applying the burden to the person (1) furthers "a compelling governmental interest"; and (2) "is the least restrictive means" of furthering that interest.54 This "strict scrutiny" standard, particularly the "least restrictive means" requirement, is "exceptionally demanding."55 Thus, in challenges by religious objectors to the application of generally applicable laws, RFRA extends "far beyond" what the "Court has held is constitutionally required."56

The initial challenges to the contraceptive coverage requirement centered on two emerging issues: (1) whether for-profit corporations were "persons" protected by RFRA;57 and (2) whether requiring employers to cover contraception to which they objected on religious grounds violated RFRA.58 The Supreme Court took up both issues as they related to closely held corporations in Burwell v. Hobby Lobby Stores, Inc., issuing a decision on June 30, 2014.59

The challengers in Hobby Lobby, which included the owners of the "nationwide chain" of arts-and-crafts stores of the same name, objected to providing health insurance coverage for four of the 20 FDA-approved methods of contraception included in the coverage requirement.60 In their view, "life begins at conception" and "facilitat[ing] access" to methods of contraception that "may operate after the fertilization of an egg" would violate their religious beliefs.61 The challengers argued that requiring them to provide insurance coverage for such contraception violated RFRA.62

The Supreme Court held that Hobby Lobby, though a corporation, was a "person" covered by RFRA.63 Although RFRA itself did not define "person," the first section of the U.S. Code, commonly known as the Dictionary Act, defined the term to include "corporations" for the purpose of "'determining the meaning of any Act of Congress, unless the context indicates otherwise.'"64 The Court reasoned that "nothing in RFRA" suggested a meaning other than the Dictionary Act definition.65 Specifically, the majority rejected HHS's argument that for-profit corporations could not "exercise" religion, reasoning that they could do so through "[b]usiness practices that are compelled or limited by the tenets of a religious doctrine."66

The Court then proceeded to analyze whether the contraceptive coverage requirement "substantially burden[ed]" the challengers' exercise of religion.67 The Court accepted their argument that providing coverage for certain forms of contraception would violate their sincerely held religious beliefs because it might enable or facilitate the "destruction of an embryo."68 According to the majority, "federal courts have no business addressing" whether "the religious belief asserted in a RFRA case is reasonable."69 The more limited judicial role, the Court said, is to determine whether the "line drawn" by the religious objectors "reflects 'an honest conviction.'"70 Because no party disputed the sincerity of the employers' convictions, the Court focused its inquiry on whether the burden imposed by the coverage requirement was substantial.71 The Court concluded that it was, because the requirement would force the challengers to either violate their religious beliefs or face "severe" economic consequences.72

The Court next considered whether the contraceptive coverage requirement nonetheless satisfied RFRA's strict scrutiny standard.73 The Court assumed, for purposes of its analysis, that applying the coverage requirement to petitioners served a "compelling governmental interest" in "guaranteeing cost-free access to the four challenged contraceptive methods."74 However, the Court concluded that the least restrictive means standard was not satisfied because HHS had "at its disposal" the accommodation process it provided to nonprofit organizations with religious objections which, in the Court's view, did not "impinge on" the challengers' religious beliefs and "serve[d] HHS's stated interests equally well."75 Accordingly, the Court held that applying the contraceptive coverage requirement to closely held corporations violated RFRA.76

On July 14, 2015, the Departments finalized a rule in response to the Hobby Lobby decision that extended the accommodation previously reserved for religious nonprofits to for-profit entities that are "not publicly traded, [are] majority-owned by a relatively small number of individuals, and object[] to providing contraceptive coverage based on [their] owners' religious beliefs."77

Legal Challenges to the Accommodation Process and Agency Responses

When the Court handed down its decision in Hobby Lobby, a separate line of legal challenges to the contraceptive coverage requirement involving the accommodation process remained unresolved by the High Court.78 In one such case, a Christian college argued that the process, which required objecting entities to submit a certification form called EBSA Form 700 to their insurers or TPAs, itself burdened its exercise of religion in violation of RFRA and the First Amendment.79 The college believed that submitting the required form would "make it morally complicit in the wrongful destruction of human life."80

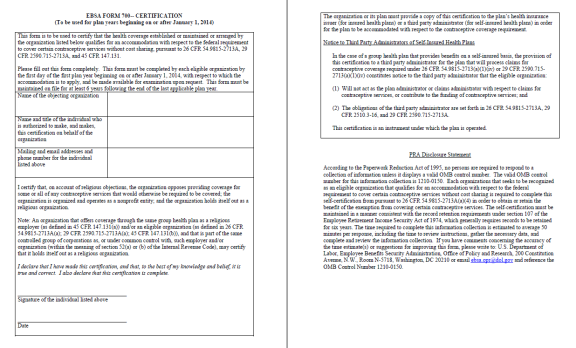

As shown in Figure 1, EBSA Form 700 had two pages: the first required the organization to certify compliance with the criteria for obtaining the accommodation and the second contained a notice to TPAs.

After a federal district court denied the college's motion to preliminarily enjoin the enforcement of the contraceptive coverage requirement,82 the college sought emergency relief from the Supreme Court.83 On July 3, 2014, three days after deciding Hobby Lobby, the Supreme Court ruled that while the college's case was on appeal to the Seventh Circuit, the college did not need to comply with the contraceptive coverage requirement or complete EBSA Form 700 so long as it "inform[ed] the Secretary of Health and Human Services in writing that it is a non-profit organization that holds itself out as religious and has religious objections to providing coverage for contraceptive services."84

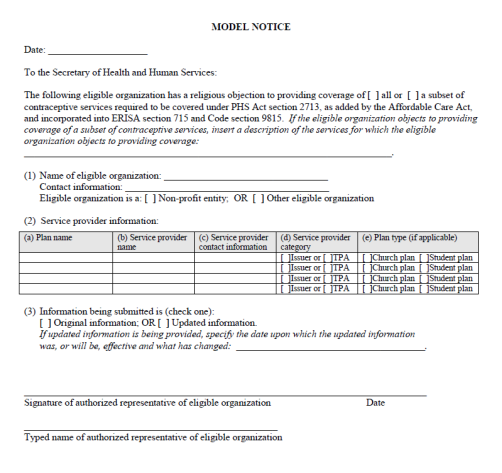

On August 27, 2014, "consistent with the Wheaton order," HHS issued an interim rule that provided eligible organizations an alternative to EBSA Form 700.85 Pursuant to this rule, organizations could opt to notify HHS, rather than their insurers or TPAs, of their eligibility for the exemption and their objections to providing coverage for some or all forms of FDA-approved contraception.86 This option (the "alternative notice process") required organizations to provide HHS with their insurers' or TPAs' names and contact information.87 After receiving the notice, those Departments would send a "separate notification" to each issuer or TPA, which, for self-insured plans, would designate the TPA as the plan administrator and constitute "an instrument under which the plan is operated."88 The model notice that HHS issued with the interim rule appears in Figure 2.89

|

|

Source: The Center for Consumer Information & Insurance Oversight, CMS.gov, https://www.cms.gov/cciio/resources/Regulations-and-Guidance/index.html#Prevention (click on "August 22, 2014 Model Notice to Secretary of HHS" under "Prevention") (last visited Sept. 23, 2019). |

After these changes in the law, the Seventh Circuit affirmed the district court's decision to deny the college a preliminary injunction.90 The appellate court reasoned that the college did not have to provide certain forms of contraception in its student benefit plans so long as it notified either its TPA or the government of its objection to providing that coverage.91 Although the government would designate the college's preexisting TPA to provide the required coverage, the court reasoned that the plan instrument became the "government's plan" rather than the college's plan.92 The court also rejected the college's argument that complying with the accommodation process would render it "complicit" in providing the contraception to which it objected.93 Writing for the court, Judge Richard Posner reasoned that "it is the law, not any action on the part of the college," that requires the TPA to provide coverage once the college has registered its objection.94 Accordingly, the court concluded that the college was unlikely to prevail on its RFRA claim.95

The Seventh Circuit was not the only appellate court to uphold the accommodation process amid requests for injunctive relief. Appellate courts in eight circuits in total concluded (at least as a preliminary matter while litigation proceeded on the merits) that the process did not impose a substantial burden on the challengers' exercise of religion.96 They rejected the view that providing notice to insurers or TPAs, or to HHS, "triggered" the provision of contraception, making the plaintiffs partially responsible for an act that violated their beliefs.97 Like the Seventh Circuit, they reasoned that the ACA, not the transmission of EBSA Form 700 or the notice to HHS, was the reason the applicable plans provided coverage for contraception without cost sharing.98 Some appellate judges dissented from their panel's decision or a denial of rehearing by the full circuit court, including now–Supreme Court Justices Neil Gorsuch and Brett Kavanaugh.99

The Eighth Circuit was the first appellate court to hold that the accommodation process violated RFRA.100 In that case, the district court had preliminarily enjoined the government from enforcing the contraceptive coverage requirement against two nonprofit employers that offered self-insured plans.101 The Eighth Circuit read Hobby Lobby to require it to "accept [the plaintiffs'] assertion that self-certification under the accommodation process—using either [EBSA] Form 700 or HHS Notice—would violate their sincerely held religious beliefs."102 And it reasoned that providing the notice resulted in the provision of contraceptive coverage even if the plaintiffs did not have to arrange for or subsidize that coverage.103 The court then concluded that the process was not the least-restrictive means of serving the government's interest in providing women with access to cost-free contraception.104 In particular, it observed that the government could require objecting organizations to notify HHS of their objections without providing "the detailed information and updates" required under the alternative notice process.105 The court also found that the government failed to demonstrate why it could not reimburse employees for their purchase of contraceptives directly or pursue other ways to make contraception more widely available.106

After the Eighth Circuit rendered its decision but before the government sought the Supreme Court's review, the Supreme Court consolidated and granted certiorari in seven other cases involving RFRA challenges to the accommodation process under the caption Zubik v. Burwell.107 However, on May 16, 2016, the Supreme Court vacated the Zubik decisions and remanded the cases to the circuit courts in light of the "significantly clarified view of the parties."108 The Court explained that in response to its request for additional briefing after oral argument, the government confirmed that "contraceptive coverage could be provided to petitioners' employees, through petitioners' insurance companies" without requiring the petitioners to notify their insurers or HHS in the manner previously required.109 The petitioners, in turn, confirmed that an insurer's independent provision of contraceptive coverage to the petitioners' employees would not burden the petitioners' religious exercise.110 The Court instructed the appellate courts on remand to afford the parties "an opportunity to arrive at an approach going forward that accommodates petitioners' religious exercise while at the same time ensuring that women covered by petitioners' health plans 'receive full and equal health coverage, including contraceptive coverage.'"111 It also enjoined the government from taxing or penalizing the petitioners based on a failure to provide notice, reasoning that the petitioners apprised the government of their religious objections through the litigation itself.112 The Court expressly declined to opine on whether the existing accommodation process substantially burdened the petitioners' religious exercise or nonetheless complied with RFRA's strict scrutiny standard.113

Executive Action After Zubik

Following the Supreme Court's remand, the executive branch took additional actions on the contraceptive coverage requirement. The Departments solicited and reviewed public comments on options to further revise the process.114 However, as of January 9, 2017, the Departments had not identified a "feasible approach . . . [to] resolve the concerns of religious objectors, while still ensuring that the affected women receive full and equal health coverage, including contraceptive coverage."115 At that time, the Departments maintained that the existing accommodation process was "consistent with RFRA."116

Following a change in presidential administrations, on May 4, 2017, President Donald J. Trump issued an executive order directing the Departments to "consider issuing amended regulations, consistent with applicable law, to address conscience-based objections to the preventive-care mandate promulgated under [42 U.S.C. §] 300gg-13(a)(4)"—the ACA provision that refers specifically to preventive care for women and pursuant to which HRSA included contraceptive coverage.117

On October 6, 2017, the Departments reversed their position on the legality of the accommodation process and issued two interim final rules (IFRs)118 that made that process "optional."119 The first rule (the Religious Exemption IFR) expanded the HRSA exemption formerly available only to houses of worship and related entities120 to include any nongovernmental organization that objected to providing or arranging coverage for some or all contraceptives based on "sincerely held religious beliefs."121 The second rule (the Moral Exemption IFR) extended the same exemption to certain nongovernmental organizations whose objections were based on "sincerely held moral convictions," rather than religious beliefs.122 Pursuant to these rules, "an eligible organization [that] pursue[d] the optional accommodation process through the EBSA Form 700 or other specified notice to HHS" would "voluntarily shift[] an obligation to provide separate but seamless contraceptive coverage to its issuer or [TPA]."123 However, if an employer or institution chose to rely on the exemption rather than the accommodation, neither the objecting entity nor its insurer or TPA would need to provide coverage for the objected-to contraceptive methods.124 The Departments also added an "individual exemption" that allowed willing employers and issuers, both governmental and nongovernmental, to provide alternative policies or contracts that did not offer contraceptive coverage to individual enrollees who objected to such coverage based on sincerely held religious beliefs or moral convictions.125

The Departments estimated that the Religious Exemption IFR "would affect the contraceptive costs of approximately 31,700 women" based on information derived from the litigating positions of various objecting entities and notices the agency received pursuant to the previous accommodation process.126 They further estimated that the total costs potentially transferred to those affected women would amount to "approximately $18.5 million."127 However, in order to "account for uncertainty" in its estimate, the agencies also examined the "possible upper bound economic impact" of the Religious Exemption IFR.128 Applying a different methodology, the Departments arrived at a figure of approximately 120,000 women, with potential transfer costs totaling $63.8 million.129 The Departments projected a smaller effect with respect to the Moral Exemption IFR, estimating that it could affect the contraceptive costs of 15 women, an aggregate effect of approximately $8,760.130

The Departments finalized the Religious and Moral Exemption IFRs on November 15, 2018, with effective dates of January 14, 2019 (collectively, the 2019 Final Rules).131 The 2019 Final Rules amended the regulatory text "to clarify the intended scope of the language" but retained the substance of the interim final rules.132 The Departments increased their upper-bound estimate of the number of women that the expanded Religious Exemption could affect from 120,000 women to 126,400 women, yielding potential transfer costs of $67.3 million.133

Post-2017 Legal Developments

The expanded exemptions generated a new set of legal challenges from states concerned with the fiscal burdens of the revised rules and the Departments' authority to promulgate them.134 In addition, some private parties (including a nationwide class of employers) successfully obtained injunctions against enforcement of the prior accommodation process after the government stopped defending the process on RFRA grounds.135 This section discusses some of the key decisions among the pending cases concerning the contraceptive coverage requirement.

Pennsylvania v. Trump

In late 2018, Pennsylvania and New Jersey asked a federal court to block the 2019 Final Rules, alleging, among other claims, that the rules (1) "failed to comply with the notice-and-comment procedures" required by the Administrative Procedure Act (APA) and (2) were "'arbitrary, capricious, an abuse of discretion, or otherwise not in accordance with law' in violation of the substantive provisions of the APA."136 After concluding that the states had standing to bring these claims,137 the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania examined whether the states were "likely to succeed" on their APA challenges—a key consideration in determining whether to issue a preliminary injunction.138 The court first considered the states' procedural APA claim that the 2019 Final Rules were invalid because the Departments failed to provide for notice and comment before issuing the interim rules. The APA's notice-and-comment requirement, the court explained, means that an agency must:

issue a general notice of proposed rulemaking; "give interested persons an opportunity to participate in the rule making through submission of written data, views or arguments . . ."; and, "[a]fter consideration of the relevant matter presented, . . . incorporate in the rules adopted a concise general statement of their basis and purpose."139

The district court reasoned that even though the Departments solicited comments before ultimately finalizing the interim rules, such "post-promulgation" efforts did not cure the procedural defect because the interim rules "fundamentally changed the 'question to be decided in the [subsequent] rulemaking.'"140 The court observed that "instead of asking whether substantial expansions to the exemption and accommodation should be made at all," the Departments "solicited comments on whether those changes should be finalized."141 For these reasons, the court concluded that the 2019 Final Rules likely violated the APA's procedural requirements.142

The court next considered whether the 2019 Final Rules were "arbitrary, capricious, an abuse of discretion, or otherwise not in accordance with law," or "in excess of statutory jurisdiction, authority, or limitations, or short of statutory right"—grounds for a reviewing court to "set aside" the rules under the APA.143 The Departments argued that (1) the ACA "include[d] a broad delegation of authority" that encompassed this rulemaking; and (2) RFRA required the Departments to issue the Religious Exemption.144

The court first concluded that the ACA did not authorize the Departments to create what the court viewed as "blanket" exceptions to the preventive services requirement.145 Reciting the statutory language, the court observed that group health plans and issuers of group or individual coverage "shall" cover "such additional preventive care . . . as provided for in comprehensive guidelines supported by [HRSA]."146 The court disagreed with the Departments' contention that HRSA's authority to define "what preventive care [would] be covered" necessarily included the authority to decide "who must provide preventive coverage."147 The court also rejected the Departments' view that such a delegation was implicit in the language "as provided for in comprehensive guidelines supported by [HRSA]," stating that it "strains credulity to say that by granting HRSA the authority to 'support' guidelines on 'preventive care,' Congress necessarily delegated to HRSA the authority to subvert the 'preventive care' coverage mandate through the blanket exemptions set out in the Final Rules."148 The court concluded that the 2019 Final Rules exceeded the Departments' authority under the ACA and thus violated the APA.149

The court also disagreed with the Departments' argument that the Religious Exemption was necessary to bring the contraceptive coverage requirement into compliance with RFRA.150 As a threshold matter, the court reasoned that whether a law's application complies with RFRA—a statute authorizing "[j]udicial [r]elief" for aggrieved persons—is primarily a judicial determination.151 The court then concluded that the Religious Exemption far exceeded what RFRA required because it provided a "blanket exemption" for religious objectors rather than one that left room for the balancing contemplated by RFRA (i.e., allowing the government to achieve its compelling interest through a least restrictive means).152

Finally, the court rejected the Departments' argument that the prior accommodation process substantially burdened the religious exercise of objecting organizations, noting that the Third Circuit already held to the contrary in Geneva College v. Secretary of HHS (one of the cases consolidated and later vacated in the Zubik litigation).153 In Geneva and a subsequent decision, the Third Circuit held that "an independent obligation on a third party"—whether the insurer providing coverage instead of the objecting employer or an employer providing coverage to its employees over the objections of some employees—"can[not] impose a substantial burden on the exercise of religion in violation of RFRA."154 For these reasons, the district court concluded that the Departments lacked the substantive authority to promulgate the 2019 Final Rules under the APA.155

Having decided that the states met the other requirements for a preliminary injunction, the court concluded that enjoining the rules on a "nationwide" basis was the appropriate remedy to afford "complete relief" to the states.156 Among other reasons, the court noted that an "injunction limited to Pennsylvania and New Jersey would, by its terms, not reach Pennsylvania and New Jersey citizens who work for out-of-state employers."157 In the court's view, a preliminary injunction would "maintain the status quo."158 The court reasoned that organizations that were eligible for an exemption or accommodation under the previous regulatory regime (i.e., before the Religious or Moral IFRs) would "maintain their status" and challengers could continue to pursue judicial relief or rely on injunctions that they previously obtained against enforcement of the contraceptive coverage requirement.159

On appeal, the Third Circuit agreed with much of the district court's reasoning and affirmed its central conclusions.160 It ruled that "the state plaintiffs are likely to succeed in proving that the [Departments] did not follow the APA and that the regulations are not authorized under the ACA or required by [RFRA]."161 The circuit court also upheld the district court's decision to issue a nationwide preliminary injunction.162 The government and an objecting entity that the district court allowed to intervene as a defendant in the case have indicated their intent to appeal the Third Circuit's ruling.163

California v. HHS

Proceeding alongside the Pennsylvania litigation was an action in the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California. In 2018, 14 states moved to enjoin enforcement preliminarily of the 2019 Final Rules.164 A subset of these states had already obtained a nationwide injunction against enforcement of the interim rules, which the Ninth Circuit then modified to apply only in the states that were plaintiffs in the action.165 In renewing their challenge to the 2019 Final Rules, the states advanced APA, Establishment Clause, and Equal Protection Clause claims.166 As with its first ruling on the interim rules,167 the district court decided the motion for injunctive relief on statutory grounds.168

After concluding that the plaintiff-states had standing, the court examined the Departments' authority to institute the expanded exemptions.169 Like the district court in the Pennsylvania action, the court reasoned that agency authority to create exemptions was "inconsistent" with Congress's directive in the ACA that nongrandfathered plans and insurers "shall" provide preventive services without cost sharing.170

The court also concluded that RFRA neither required nor authorized the Religious Exemption.171 It emphasized that a threshold question under RFRA is whether the law "substantially burdens" a person's exercise of religion.172 Under the Ninth Circuit's RFRA precedent, the court explained, "a 'substantial burden' is imposed only when individuals are forced to choose between following the tenets of their religion and receiving a governmental benefit . . . or coerced to act contrary to their religious beliefs by the threat of civil or criminal sanctions."173 The district court observed that of the nine circuits to have considered the question, all but one (the Eighth Circuit) concluded that the prior accommodation process did not impose a substantial burden on objectors' exercise of religion.174 Unlike the Eighth Circuit, the district court reasoned that whether a burden is "substantial" is an "objective legal matter," not to be determined by deferring to the objectors' claims.175 The district court agreed with the analysis of the Eleventh Circuit and other courts that "under the accommodation 'the only action required of the eligible organization is opting out: literally, the organization's notification of its objection,' at which point all responsibilities related to contraceptive coverage fall upon its insurer or TPA."176 The district court concurred with these courts, too, that providing notice did not substantially burden an objector's religious exercise by making it "complicit" in the provision of contraception because "it is the ACA and the guidelines that entitle plan participants and beneficiaries to contraceptive coverage, not any action taken by the objector."177

The district court further concluded that there were "serious questions going to the merits" of the case as to whether the Religious Exemption was even permissible, let alone required.178 First, it questioned whether the expanded exemption violated the Establishment Clause in light of the Supreme Court's proviso that "[a]t some point, accommodation may devolve into an unlawful fostering of religion."179 Second, the court observed that while the Supreme Court has mandated that courts "take adequate account of the burdens a requested accommodation may impose on nonbeneficiaries,"180 there is "substantial debate among commentators as to how to assess the legality of accommodations not mandated by RFRA when those accommodations impose harms on third parties"—women who would otherwise receive contraceptive coverage under the law.181

Ultimately, the district court issued a preliminary injunction against enforcement in the plaintiff states based on the likelihood that the 2019 Final Rules violated the APA.182 The court reserved for the merits stage of the litigation the possibility of additional rulings on the underlying legal disputes regarding the scope of RFRA and the rules' compliance with the Establishment Clause.183 The district court anticipated that its preliminary injunction would preserve the "status quo" of the exemptions and the accommodation process that existed before the Departments issued the Religious and Moral IFRs.184 The Ninth Circuit is currently reviewing the district court's decision.185

Massachusetts v. HHS

A lawsuit by the Commonwealth of Massachusetts to block the enforcement of the interim rules—and later the final rules—instituting the expanded exemptions was initially barred on standing grounds.186 The district court rejected the Commonwealth's primary standing argument that the expanded exemptions threatened fiscal injury to the state.187 In essence, the Commonwealth had alleged that as more employers availed themselves of the exemptions, Massachusetts would need to assume the costs of contraceptive coverage for qualifying residents as well as prenatal and postnatal care resulting from unintended pregnancies.188 The district court found this argument too speculative.189

On May 2, 2019, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the First Circuit reversed the district court's ruling,190 holding that Massachusetts had shown an "imminent" harm "fairly traceable" to the expanded exemptions, sufficient to confer standing.191 The court determined that the Commonwealth had demonstrated through the Departments' own regulatory impact estimates and data that there was a "substantial risk" that "some women in Massachusetts" would lose coverage and that it was "highly likely" that three Massachusetts employers with health plans exempt from state regulation (one of which was Hobby Lobby) would utilize the expanded exemptions.192 Even though the Commonwealth's argument "proceed[ed] in steps,"193 the "causal chain" from loss of coverage to use of state-funded services at the Commonwealth's expense was not too "attenuated" and relied on "probable market behavior."194 The appellate court remanded the case to the district court to consider the parties' substantive arguments.195 The parties' motions for summary judgment—asking the court for a ruling on the legal issues prior to (and ultimately in lieu of) a trial—are pending before the district court.196

DeOtte v. Azar

While the Pennsylvania and California actions resulted in preliminary injunctions against the 2019 Final Rules, the Departments are also enjoined from enforcing the prior accommodation process in key respects as a result of a nationwide injunction issued by the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Texas.197 In DeOtte v. Azar, the court certified two classes of objectors to the contraceptive coverage requirements.198 The "Employer Class" consisted of:

Every current and future employer in the United States that objects, based on its sincerely held religious beliefs, to establishing, maintaining, providing, offering, or arranging for: (i) coverage or payments for some or all contraceptive services; or (ii) a plan, issuer, or third-party administrator that provides or arranges for such coverage or payments.199

The "Individual Class" consisted of:

All current and future individuals in the United States who: (1) object to coverage or payments for some or all contraceptive services based on sincerely held religious beliefs; and (2) would be willing to purchase or obtain health insurance that excludes coverage or payments for some or all contraceptive services from a health insurance issuer, or from a plan sponsor of a group plan, who is willing to offer a separate benefit package option, or a separate policy, certificate, or contract of insurance that excludes coverage or payments for some or all contraceptive services.200

The court granted these classes summary judgment on their RFRA claims.201 Similar to the Eighth Circuit's reasoning, the district court concluded with respect to the Employer Class that the court could not question the lead plaintiff's position "that the act of executing the accommodation forms is itself immoral."202 As for the Individual Class, the court accepted the plaintiffs' argument that purchasing plans that cover certain forms of contraception substantially burdens their religious exercise because it makes them "complicit" in the provision of contraception to which they object.203 Having found that the requirement imposed a substantial burden on these groups, the court then concluded that the requirement was insufficiently tailored.204 It reasoned that "[i]f the Government has a compelling interest in ensuring access to free contraception, it has ample options at its disposal that do not involve conscripting religious employers" or requiring the participation of objecting employees.205

The district court permanently enjoined the government from enforcing the contraceptive coverage requirement against any member of the Employer Class to the extent of its objection.206 It further enjoined the government from preventing a "willing" employer or insurer from offering Individual Class members plans that do not include contraceptive coverage.207 In its final order specifying the terms of its nationwide, permanent injunction, the court included a "safe harbor" allowing the Departments to (1) ask employers or individuals whether they are sincere religious objectors; (2) enforce the contraceptive coverage requirement with respect to employers or individuals who "admit" they are not sincere religious objectors; and (3) seek a declaration from the court that an employer or individual falls outside the certified classes if the government "reasonably and in good faith doubt[s] the sincerity of that employer or individual's asserted religious objections."208

Before entering final judgment, the district court denied the State of Nevada's motion to intervene (supported by 22 additional states) in the litigation.209 Nevada has appealed that denial and the court's injunction to the Fifth Circuit.210

Considerations for Congress

Although the contraceptive coverage requirement remains in effect,211 the injunctions discussed above leave its implementation and enforcement in an uncertain posture. In combination, these rulings affect the regulatory frameworks that existed both before and after the promulgation of the expanded exemptions. The injunctions entered in the Pennsylvania and California actions do not bar entities that qualified for an exemption or an accommodation before the Religious or Moral Exemption IFRs from availing themselves of those options.212 Accordingly, it appears that (1) qualifying institutions (e.g., houses of worship) can still invoke the exemption for religious employers; and (2) "eligible organizations"—including closely held corporations as defined in the 2015 rule—can still use the accommodation process.213

However, as a result of the injunctions entered in DeOtte and other cases concerning the accommodation, the government is more limited in its ability to enforce the requirement against entities that choose not to notify their insurers or HHS of their objections. For example, regardless of an entity's compliance with the accommodation process, the government may not enforce the requirement against employers within the Employer Class (i.e., those that object to providing or arranging for contraceptive coverage based on sincerely held religious beliefs), at least to the extent of those employers' objections.214 And the government may not prevent employers or insurers from offering plans without contraceptive coverage to individuals who oppose that coverage based on sincere religious beliefs.215 The DeOtte injunction does not bar the government from (1) enforcing the contraceptive coverage requirement against employers "who admit that they are not sincere religious objectors"; (2) asking employers who fail to comply with the coverage requirement whether they are sincere religious objectors; or (3) challenging an employer's claim to have a sincere religious objection in federal court.216 In addition, because the Third Circuit has preliminarily blocked enforcement of the Moral Exemption nationwide, and because the DeOtte injunction extends only to employers with religious objections, it appears that, as a general matter, the government is not barred from enforcing the requirement against entities with ethical or moral, but not religious, objections to contraception.217 However, injunctions entered in other cases may preclude enforcement against particular parties.218 Further direction from the Departments or the courts following review on the merits may clarify the scope of the coverage requirement.219

Beyond the effects of the recent injunctions, the ongoing litigation reflects a broader public policy debate over the extent to which the government should accommodate entities with religious or moral objections to contraception, particularly when those accommodations may compromise their employees' or students' access to the full range of contraceptive services covered for other women. The complex legal questions stemming from this public policy debate remain largely unresolved five years after Hobby Lobby. Over the years, individual Members of Congress have weighed in on this topic,220 and Congress, if interested, could do so as a whole to clarify the legal landscape. A number of approaches have been proposed that would recalibrate the legal framework for contraceptive coverage, including those that would have the government take a more active role in facilitating access to contraception and others that would attempt to clarify the responsibilities of the government in accommodating those with genuine religious objections to a coverage requirement.

Some lawmakers have proposed amendments to the ACA's preventive services coverage requirements "with respect to women"221 to explicitly require coverage of contraception. For example, a bill introduced in the last Congress would have amended subsection (a)(4) to include "contraceptive care," including "the full range of [FDA-approved] female-controlled contraceptive methods" and "instruction in fertility awareness-based methods . . . for women desiring an alternative method."222 Other proposals, including a bill introduced this Congress, would direct the Departments to include certain forms of contraception at the regulatory level.223

In general, legislation specifying that contraception is among the required preventive health services may help tip the scales on the government interest prong of the RFRA analysis toward a compelling interest in providing cost-free coverage for contraception through employer-sponsored health plans. In Hobby Lobby, the Supreme Court assumed that the government had a compelling interest in "guaranteeing cost-free access" to the objected-to contraceptive methods.224 However, the majority noted that "there are features of ACA that support" the opposing view, in particular, the inapplicability of the requirement to grandfathered plans.225 The Departments went a step further in the 2019 Final Rules, suggesting that the government did not have a compelling interest in contraceptive coverage because Congress left the decision of whether to include it to the agencies.226 Codifying the requirement may respond to arguments of this nature. However, proposals to expand contraceptive coverage, standing alone, could still be susceptible to challenge by religious objectors who might still assert that laws mandating coverage—even if they include some exemptions—impose a substantial burden on their religious exercise and are not narrowly tailored under RFRA.227

RFRA applies by default to all federal statutes adopted after its enactment (November 16, 1993) "unless such law explicitly excludes such application by reference to this Act."228 Some legislation concerning contraception includes language excepting those provisions from RFRA or excluding RFRA claims.229 A pair of bills introduced in the wake of Hobby Lobby would have prohibited an "employer that establishes or maintains a group health plan for its employees" from "deny[ing] coverage of a specific health care item or service . . . where the coverage of such item or service is required under any provision of Federal law or the regulations promulgated thereunder," notwithstanding RFRA.230 Lawmakers have also proposed amendments to RFRA itself. Similar bills introduced in both chambers this Congress would provide that RFRA's strict scrutiny standard does not apply to certain types of laws, including "any provision of law or its implementation that provides for or requires . . . access to, . . . referrals for, provision of, or coverage for, any health care item or service."231

Laws that make RFRA inapplicable to the contraceptive coverage requirement would not foreclose challenges based on the Free Exercise Clause.232 However, as previously noted, Free Exercise claims are potentially subject to a less stringent standard of review than RFRA-based objections because of the Supreme Court's holding in Employment Division v. Smith that the Free Exercise Clause typically does not require the government to provide religious-based exemptions to generally applicable laws.233

Other approaches to contraceptive coverage have focused on accommodating the interests of religious objectors. Some courts and objecting employers have suggested that Congress could avoid or minimize burdens on religious objectors by funding separate contraceptive coverage or expanding access to programs that provide free contraception instead of requiring employers to provide this coverage.234 Along these lines, the Departments have separately issued a rule to give the directors of federally funded family planning projects the authority to extend contraceptive services to some women whose employers do not provide coverage for such services because of a religious or moral exemption.235 (This rule is also the subject of pending litigation.236) While the efficacy of such proposals in maintaining or increasing access to contraception is beyond the scope of this report, alternatives that do not involve requiring private parties to provide contraceptive coverage or otherwise take an action that results in the provision of coverage by a third party could reduce the potential for both RFRA and Free Exercise challenges.237

Other proposals seek to codify exemptions to the contraceptive coverage requirement for entities with religious or moral objections. For example, the Religious Liberty Protection Act of 2014 would have prohibited HHS from "implement[ing] or enforc[ing]" any rule that "relates to requiring any individual or entity to provide coverage of sterilization or contraceptive services to which the individual or entity is opposed on the basis of religious belief."238 That bill also would have included a "special rule" in the ACA stating that a "health plan shall not be considered to have failed to provide" the required preventive health services "on the basis that the plan does not provide (or pay for) coverage of sterilization or contraceptive services because—(A) providing (or paying for) such coverage is contrary to the religious or moral beliefs of the sponsor, issuer, or other entity offering the plan; or (B) such coverage, in the case of individual coverage, is contrary to the religious or moral beliefs of the purchaser or beneficiary of the coverage."239 Enacting statutory exemptions to the contraceptive coverage requirement might avoid future litigation over the Departments' authority under the ACA to create categorical exemptions.240 In addition, broader exemptions could reduce the potential for RFRA or Free Exercise challenges. At the same time, they could increase the prospect of Establishment Clause challenges like those brought in response to the expanded exemptions in the 2019 Final Rules.241 While the Supreme Court has said that "there is room for play in the joints" between the Free Exercise Clause and the Establishment Clause,242 it remains to be seen whether broad accommodations like the Religious Exemption and the Moral Exemption fit comfortably in that space.243

In the five years since the Hobby Lobby decision, the Departments promulgated six different rules concerning the contraceptive coverage requirement, a change in presidential administration marked a turning point in the Departments' RFRA calculus, and the Supreme Court underwent its own changes with the appointment of two new Justices. As lower courts continue to adjudicate challenges to the requirement in its most recent iterations, Congress, the Executive, and the Judiciary may all have a role to play in defining the interests at stake and the balance to be achieved in the years ahead.