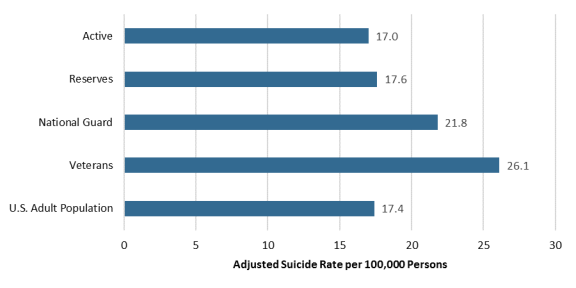

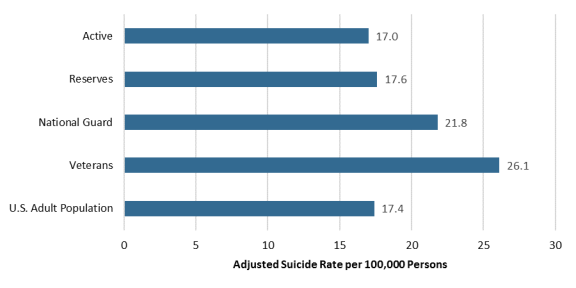

In the past decade, federal and state governments have made a sustained effort to improve suicide prevention and response for the Armed Forces through funding, oversight, and legislation to enhance mental health and resiliency programs. The Department of Defense's Suicide Prevention Office (DSPO) has reported that overall military suicide rates for the Active and Reserve Components are generally comparable with those of the general U.S. population when adjusting for demographics (i.e., the military is younger and has a greater percentage of men than the general U.S. population). However, the suicide mortality rate for the National Guard (NG)—a segment of the Reserve Component—has been consistently higher than that for active component members, other reservists, and a demographically similar portion of the general population. Only the veteran population has had an equivalent or higher adjusted suicide rate. This raises questions as to whether there are risk factors that are unique to service in the Guard that could be driving the difference. Figure 1 compares the CY2016 adjusted suicide rates for military components relative to veterans and the general population.

|

Figure 1. Comparison of Adjusted Military Suicide Rates

CY2016

|

|

|

Source: CRS consolidation of adjusted suicide rates from DOD and Department of Veterans Affairs reports for CY2016 (the most current adjusted data available).

Notes: Military and veteran suicide rates are adjusted for age and sex. The civilian suicide rate is based on CDC data for suicide rates for the adult population (age 17-59). The CDC rate for the entire population (including infants, children, and the elderly) for CY2016 was 13.5 per 100,000 people. For the purpose of this data, a veteran is defined as someone who had served in an active component or been activated for federal military service and was not currently serving at the time of his or her death.

|

Selected Risk Factors for National Guard and Reserves

Some suicide risk factors are common across all military services and components. These include exposure to combat trauma or stress, combat-related illness or injury, increased access to firearms (relative to civilians), and post-deployment reintegration issues. However, there may be some factors that are unique to the Guard and Reserve or have a greater impact on these troops due to the dual nature of their employment. These factors are discussed below.

Access to Mental and Behavioral Health Care

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has identified barriers to accessing mental health treatment as an indicated risk factor for suicide. Active component servicemembers are eligible to receive health care services (TRICARE Prime), including mental and behavioral health care, with no out-of-pocket costs. Most members of the National Guard and Reserves, and their families, are eligible for TRICARE Reserve Select (TRS) coverage. TRS requires monthly premiums, deductibles, and cost shares when receiving care from participating TRICARE providers. While surveys have shown that members of the National Guard and Reserve are broadly satisfied with their care under these policies, access and affordability remain concerns. Access to civilian health care providers participating in TRICARE's network can be limited in remote or rural locations. Cost sharing for mental and behavioral health visits to out-of-network providers can be prohibitively expensive for some families. In addition, approximately 20% of those who are eligible for TRS are enrolled. Those not enrolled in TRS may be covered by employer-sponsored insurance programs, Medicare, private individual insurance, or may be uninsured. DOD generally does not collect information on alternate insurance coverage for reservists not covered by TRS. As such, it is unclear whether members of National Guard have adequate coverage for mental and behavioral health care services and to what extent they are using those services.

Employment and Income Security

Financial stress can also contribute to depression and suicidality. A recent study of the Army National Guard (ARNG) cites unemployment, underemployment, and income insecurity as associated circumstances in approximately 20% of suicides between 2007 and 2014. Financial woes can also limit a member's ability to cover health care costs. Active duty members get full-time pay and benefits from DOD. Due to the part-time nature of Reserve work, most members are primarily employed in the civilian sector. Members of the Guard are unique in that they may be called to federal or state service. Calls to state service are typically shorter than federal deployments; however, shorter or more frequent activations might be more disruptive to civilian employment. Federal law (the Uniformed Services Employment and Reemployment Rights Act of 1994) protects members of the Reserves from discrimination by employers and ensures continued employment following a call to federal service. While state laws might provide employment protections, it is possible that Guardsmen would not be covered under all circumstances.

Several federal government agencies, including DOD, Department of Labor and Department of Veterans Affairs, offer employment and training services for reservists and veterans. Nevertheless, access to these programs may be a challenge for members in living in remote areas. In addition, some members of the Guard may struggle to find full-time jobs that provide adequate compensation or may experience disruption and issues reintegrating into the civilian workplace following a call to service.

Community Support

DOD data suggest that National Guard suicides more frequently occur when members are not on active duty. Active duty members typically have daily interactions with commanders and members of their units, and are likely to live on or near military installations. This provides more opportunities for commanders and peers to recognize warning signs for mental health issues and to refer troops to resources such as chaplains, counselors, or other military support programs. The National Guard and Reserves, on the other hand, have infrequent interactions with their military coworkers (e.g., drill weekends, annual training), thus limiting military leader's ability to recognize and respond to warning signs or troubling trends in individual behavior. In addition, pervasive feelings of isolation, made more acute by the absence of military colleagues, are a risk factor for suicide and have potential to contribute to the higher suicide rates for both veterans and reservists.

The Yellow Ribbon Reintegration Program (YRRP), established by the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2008 (P.L. 110-181), is one program that seeks to connect National Guard and Reserve members and their families to community resources that can support well-being and integration. Research on YRRP has been limited; some studies have found that the program is effective in filling knowledge gaps for available resources, and is associated with other positive reintegration outcomes. Other community resiliency programs for reservists are authorized under 10 U.S.C. §10219.

Considerations for Congress

The dual civilian-military and federal-state nature of National Guard work can complicate the delivery of benefits and services to this population. Nevertheless, while the National Guard and the Reserves share some common risk factors, there are unexplained differences in the suicide rates between the two components. Some areas for congressional consideration include:

- Whether other individual (e.g., education, income) or community (e.g., remote or rural location) factors contribute to the difference between National Guard and Reserve suicide rates;

- Whether modifications should be made to reserve TRICARE benefits to encourage greater access and continuity of care for mental and behavioral health;

- Whether additional mechanisms are needed to increase awareness of or expand access to existing reintegration and employment support programs;

- How to balance federal and state support programs, and how to identify gaps and overlap;

- Whether to extend the authority for Reserve Component suicide prevention and resiliency programs (10 U.S.C. §10219) beyond the current sunset date of October 1, 2020.