Introduction

Article III, Section I of the Constitution provides that the "judicial Power of the United States, shall be vested in one supreme Court, and in such inferior Courts as the Congress may from time to time ordain and establish." Consequently, Congress determines through legislative action both the size and structure of the federal judiciary. For example, the size of the federal judiciary is determined, in part, by the number of U.S. circuit and district court judgeships authorized by Congress.1 Congress has, at numerous times over the years, authorized an increase in the number of such judgeships in order to meet the workload-based needs of the federal court system.

The Judicial Conference of the United States, the national policymaking body of the federal courts,2 makes biennial recommendations to Congress to assist it in identifying any U.S. circuit and district courts that may be in need of additional judgeships. The most recent recommendations for new U.S. circuit and district court judgeships were released by the Judicial Conference in March 2019.3

U.S. Circuit Courts

U.S. courts of appeals, or circuit courts, take appeals from U.S. district court decisions and are also empowered to review the decisions of many administrative agencies. When hearing a challenge to a district court decision from a court located within its geographic circuit, the task of a court of appeals is to determine whether or not the law was applied correctly by the district court.4 Cases presented to U.S. circuit courts are generally considered by judges sitting in three-member panels (circuit courts do not use juries).

The nation is divided into 12 geographic circuits, each with a U.S. court of appeals. There is also one nationwide circuit, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit, which has specialized subject matter jurisdiction.5

Altogether, 179 judgeships for these 13 circuit courts are currently authorized by law (167 for the 12 regional circuits and 12 for the Federal Circuit). The First Circuit (comprising Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Puerto Rico) has the fewest number of authorized judgeships, 6, while the Ninth Circuit (comprising Alaska, Arizona, California, Hawaii, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, Oregon, and Washington) has the most, 29.6

U.S. District Courts

U.S. district courts are the federal trial courts of general jurisdiction. These trial courts determine facts and apply legal principles to resolve disputes.7 Trials are conducted by a district court judge (although a U.S. magistrate judge may also conduct a trial involving a misdemeanor).

Each state has at least one district court (there is also one district court in each of the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico). States with more than one district court are divided into judicial districts, with each district having one district court. For example, California is divided into four judicial districts—each with its own district court. Altogether there are 91 U.S. district courts.8

There are 673 Article III U.S. district court judgeships currently authorized by law.9 Congress has authorized between 1 and 28 judgeships for each U.S. district court. Specifically, the district court for the Eastern District of Oklahoma (Muskogee) has 1 authorized judgeship, the smallest number among U.S. district courts. The district courts located in the Southern District of New York (Manhattan) and the Central District of California (Los Angeles) each have 28 authorized judgeships, the most among U.S. district courts.

The Role of Congress in Creating New Judgeships

Congress first exercised its constitutional power to determine the size and structure of the federal judiciary with passage of the Judiciary Act of 1789.10 The act authorized 19 judgeships, 13 for district courts and 6 for the Supreme Court.11 Congress, however, began expanding the size of the judiciary almost immediately—adding two additional district court judgeships in 1790 and another in 1791.12

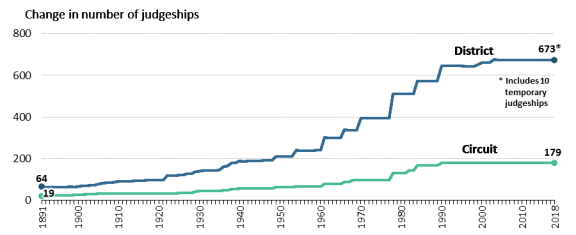

Changes in the Number of U.S. Circuit and District Court Judgeships from 1891 through 2018

As the population of the country increased, its geographic boundaries expanded, and federal case law became more complex, the number of judgeships authorized by Congress continued to increase during the 19th and 20th centuries. By the end of 1900 Congress had, under Article III, authorized a total of 28 U.S. circuit court judgeships and 67 district court judgeships.13

By the end of 1950, there were an additional 37 circuit court judgeships authorized (for a total of 65) and 145 additional district court judgeships (for a total of 212). By the end of 2000, there were a total of 179 circuit court judgeships and 661 district court judgeships.14 At present, there remain 179 circuit court judgeships, while the number of district court judgeships has increased to 673.15

Figure 1 shows the change, over time, in the number of U.S. circuit and district court judgeships authorized by Congress from 1891 through 2018.

U.S. Circuit Court Judgeships

The largest increase in the number of circuit court judgeships occurred in 1978 during the 95th Congress when the number of judgeships increased by 35, from 97 to 132. The second-largest increase occurred in 1984 during the 98th Congress when the number of judgeships increased by 24, from 144 to 168. The next-largest increase in circuit court judgeships also occurred during the 97th Congress—in 1982 the number of circuit court judgeships increased by 12, from 132 to 144.16 The 12 judgeships authorized by Congress in 1982 were for the newly established U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit.17

The number of circuit court judgeships increased to 179 in 1990 during the 101st Congress and has remained at that number to the present day. This represents the longest period of time since the creation of the U.S. courts of appeals in 1891 that Congress has not authorized any new circuit court judgeships.18

U.S. District Court Judgeships

The largest increase in the number of district court judgeships occurred in 1978 during the 95th Congress when the number of judgeships increased by 117, from 394 to 511.19 The next-largest increase in district court judgeships occurred in 1990 during the 101st Congress when the number of judgeships increased by 74, from 571 to 645. The third-largest increase in the number of district court judgeships occurred in 1961 during the 87th Congress when the number of judgeships increased by 62, from 241 to 303.20

The number of permanent21 district court judgeships increased to 663 in 2003 during the 108th Congress and has remained at that number to the present day.22 This represents the longest period of time since district courts were established in 1789 that Congress has not authorized any new permanent district court judgeships.23

Ratio of District Court Judgeships to Circuit Court Judgeships

The ratio of the number of authorized district court judgeships to circuit court judgeships has also varied during this period. In 1899 there were 2.3 district court judgeships authorized for every circuit court judgeship (this was the lowest value in the ratio of district to circuit court judgeships). In contrast, in 1970 there were 4.1 district court judgeships authorized for every circuit court judgeship (this was the highest value in the ratio of district to circuit court judgeships).

The median ratio of district court judgeships to circuit court judgeships during the entire period (from 1891 through 2018) was 3.5. Most recently, for each year from 2010 through 2018, there were 3.8 district court judgeships for every circuit court judgeship authorized by Congress.

Temporary Judgeships

In some instances, Congress has authorized the creation of temporary judgeships rather than permanent judgeships.24 A permanent judgeship, as the term suggests, permanently increases the number of judgeships in a district or circuit, while a temporary judgeship increases the number of judgeships in a district or circuit for a limited period of time.25

Temporary judgeships are sometimes considered preferable by Congress if a court is dealing with an increased workload deemed to be temporary in nature (e.g., when workload increases as a result of new federal legislation or a recent Supreme Court ruling) or if Congress is uncertain about whether a recent workload increase is temporary or permanent in nature.

Once a temporary judgeship is created, Congress may later choose to extend the existence of a temporary judgeship beyond the date it was initially set to lapse or expire.26 When extending a temporary judgeship, Congress specifies the number of years the judgeship will continue to exist. Congress can also convert a temporary judgeship to a permanent one.27

If Congress does not extend a temporary judgeship or change it to a permanent one, the temporary judgeship eventually lapses.28 If a judgeship lapses it means that, for the court with the temporary judgeship, the first vacancy on or after a specified date is not filled. By not filling the first vacancy that arises after a temporary judgeship lapses, the number of judgeships for a court returns to the number authorized by Congress prior to the authorization of the temporary judgeship.

At present, there are 179 permanent U.S. circuit court judgeships and no temporary circuit court judgeships. Additionally, there are 663 permanent U.S. district court judgeships and 10 temporary district court judgeships. These temporary judgeships are listed alphabetically by state in Table 1.

|

Judicial District |

Date First Authorizeda |

Date Judgeship Is Set to Lapseb |

|

Northern District of Alabama |

11/02/2002c |

09/17/2020 |

|

District of Arizona |

11/02/2002 |

07/08/2020 |

|

Central District of California |

11/02/2002 |

04/27/2020 |

|

Southern District of Florida |

11/02/2002 |

07/31/2020 |

|

District of Hawaii |

12/01/1990d |

04/07/2020 |

|

District of Kansas |

12/01/1990 |

05/21/2020 |

|

Eastern District of Missouri |

12/01/1990 |

05/20/2020 |

|

District of New Mexico |

11/02/2002 |

07/14/2020 |

|

Western District of North Carolina |

11/02/2002 |

04/28/2020 |

|

Eastern District of Texas |

11/02/2002 |

09/30/2020 |

Source: Congressional Research Service.

Note: This table lists the 10 temporary U.S. district court judgeships that exist as of September 1, 2019.

a. All of the temporary judgeships listed in Table 1 were most recently extended by the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2019 (P.L. 116-6, February 15, 2019).

b. A vacancy occurring on or after this date for the court listed will not be filled. However, the date presented in Table 1 is applicable only if Congress does not further extend the judgeship or convert it to a permanent judgeship.

c. The seven temporary judgeships listed in Table 1 that were created on this date were authorized by P.L. 107-273.

d. The three temporary judgeships listed in Table 1 that were created on this date were authorized by P.L. 101-650.

Legislation Creating New Judgeships Since 1977

Congress has a variety of legislative vehicles at its disposal to establish new U.S. circuit and district court judgeships. Legislation that authorizes new judgeships must pass both the House and Senate (and is also subject to a presidential veto). Such legislation does not always involve either or both of the House and Senate Judiciary Committees. As discussed further below, Congress has sometimes used the appropriations process to provide the judiciary with additional district court judgeships.

Omnibus Judgeship Bills

If it desires to create a relatively large number of judgeships at one time, Congress may choose to use an "omnibus judgeships bill."

An omnibus judgeships bill, for the purposes of this report, is either a stand-alone bill or a title of a larger bill concerned exclusively or mostly with the creation of federal judgeships.29 Since 1977 Congress has enacted three omnibus judgeship bills, with the most recent omnibus bill enacted in 1990. Information related to these three pieces of legislation is presented in Table 2.

|

Bill |

Citation |

Date Enacted |

Description |

|

Omnibus Judgeship Act of 1978 |

10/20/1978 |

Created 35 circuit court judgeships and 117 district court judgeships (113 permanent and 4 temporary) |

|

|

Bankruptcy Amendments and Federal Judgeship Act of 1984 |

07/10/1984a |

Created 24 circuit court judgeships and 61 district court judgeships (53 permanent and 8 temporary) |

|

|

Federal Judgeship Act of 1990 |

12/01/1990 |

Created 11 circuit court judgeships and 74 district court judgeships (61 permanent and 13 temporary) |

Source: Congressional Research Service.

Note: This table shows omnibus judgeship bills from 1977 through 2018 that created new U.S. circuit and district court judgeships.

a. For the circuit court judgeships created by the act, the legislation stated that the "President shall appoint, by and with the advice and consent of the Senate, no more than 11 of such judges prior to January 21, 1985." For the district court judgeships created by the act, the legislation stated that the "President shall appoint, by and with the advice and consent of the Senate, no more than twenty-nine of such judges prior to January 21, 1985."

Each of the three omnibus bills was first introduced in the House and referred to the House Committee on the Judiciary. The Omnibus Judgeship Act of 1978 passed the House in its final form by a vote of 292-112 and the Senate by a vote of 67-15. The Bankruptcy Amendments and Federal Judgeship Act of 1984 passed the House in its final form by a vote of 394-0 and the Senate by voice vote. Most recently, the Federal Judgeship Act of 1990 passed both the House and Senate in its final form by voice vote.

Each of the three bills was passed in a different political context (in terms of whether there was unified or divided party control of the presidency and Congress). In 1978, there was unified Democratic control of the presidency, the Senate, and the House. In 1984, there was divided party control—with Republicans controlling the presidency and Senate while Democrats were the majority party in the House. Finally, in 1990, there was also divided party control—with Republicans controlling the presidency and Democrats holding majorities in both the Senate and House.

Since the last omnibus judgeships bill passed Congress in 1990, the overall workload of U.S. circuit and district courts has increased. From 1990 through the end of FY2018, filings in the U.S. courts of appeals increased by 15%, while filings in U.S. district courts increased by 39%. In terms of specific types of cases, civil cases increased by 34% during the same period, and cases involving criminal felony defendants increased by 60%. For civil cases, the greatest growth occurred in cases related to personal injury liability; many of these filings are part of multidistrict litigation actions involving pharmaceutical cases.30

Appropriations and Authorization Bills

In the past, Congress has at times created a relatively smaller number of judgeships through other legislative vehicles. In recent years this has been the most common method of creating new judgeships, with Congress authorizing a relatively small number of new judgeships using appropriations and authorization bills.

This has occurred on three occasions in the past 19 years and has involved only the creation of new district court judgeships (not circuit court judgeships). Overall, 34 new district court judgeships were created between 1999 and 2003 using appropriations and authorization bills. Information related to these three pieces of legislation is presented in Table 3.

|

Bill |

Citation |

Date Enacted |

Description |

|

Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2000 |

11/29/1999 |

Created 9 district court judgeships |

|

|

District of Columbia Appropriations Act, 2001a |

12/21/2000 |

Created 10 district court judgeships |

|

|

21st Century Department of Justice Appropriations Authorization Act |

11/02/2002b |

Created 15 district court judgeships (8 permanent and 7 temporary)c |

Source: Congressional Research Service.

Note: This table shows appropriation and authorization bills from 1977 through 2018 that created new U.S. district court judgeships.

a. The act also contained Commerce, Justice, and State appropriations.

b. The effective date was 07/15/2003.

c. The act also converted four temporary district court judgeships to permanent judgeships.

The Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2000 received final approval in the House by a vote of 296-135 and in the Senate by a vote of 74-24. The District of Columbia Appropriations Act of 2001 passed in its final form in the House by a vote of 206-198 and in the Senate by a vote of 48-43. The 21st Century Department of Justice Appropriations Authorization Act passed in its final form in the House by a vote of 400-4 and in the Senate by a vote of 93-5.

Each of the three bills was passed during periods of divided party control. In 1999 and 2000, Democrats held the presidency while Republicans held both the House and Senate. In 2002, Republicans held the presidency and were the majority party in the House while Democrats were the majority party in the Senate.

Congress has also routinely used appropriations bills to extend temporary district court judgeships that were initially authorized in prior years.31 Additionally, Congress has used an authorization bill to convert several temporary district court judgeships to permanent ones.32

Bills That Restructure the Judiciary

Finally, Congress may choose to establish new judgeships when passing an act that would, at least in part, restructure the federal judiciary. This occurred, for example, in 1982 when Congress created the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit. The creation of the Federal Circuit was a partial restructuring of the judiciary by Congress, as it led to merging the U.S. Court of Customs and Patent Appeals with the appellate jurisdiction of the U.S. Court of Claims to create the new Federal Circuit.33 In creating the new court, Congress authorized 12 permanent circuit court judgeships.34

Biennial Recommendations by the Judicial Conference for New Judgeships

While Congress is constitutionally responsible for determining the size and structure of the federal judiciary, the judiciary itself can recommend legislation that alters or affects the size and structure of the federal court system. This includes legislation to increase the number of U.S. circuit and district court judgeships (and to identify which judicial circuits and districts are most in need of new judgeships).

The Judicial Conference of the United States, the national policymaking body for the federal courts,35 is the institutional entity within the judiciary that is responsible for making the judiciary's recommendations for new judgeships. The Judicial Conference may recommend to Congress that new judgeships be either permanent or temporary. Additionally, the Judicial Conference may recommend that a temporary judgeship be extended or converted into a permanent one, or that a judgeship serving multiple districts be assigned to a single judicial district or dual districts.36

The Judicial Conference makes its judgeship recommendations biennially, typically in March or April at the beginning of a new Congress.37

Process Used to Evaluate Need for New Judgeships

In long-standing practice, the Judicial Conference, through its committee structure, periodically reviews and evaluates the judgeship needs of all U.S. circuit and district courts. Specifically, the Conference uses a formal survey process to determine if any courts require additional judges in order to appropriately administer civil and criminal justice in the federal court system.38

The multistep survey process is conducted biennially by the Conference's Subcommittee on Judicial Statistics39 and takes into account current workload factors and the local circumstances of each court. The process is very similar for both the courts of appeals and the district courts.

First, a court submits a detailed justification for additional judgeships to the Subcommittee on Judicial Statistics.40 The subcommittee then reviews and evaluates the court's request and prepares an initial recommendation that is given to both the court and the judicial council for the circuit where the requesting court is located.41

The circuit judicial council itself then reviews the new judgeship request and makes its recommendation to the subcommittee (which subsequently does a second analysis using the most recent caseload data). The subcommittee prepares its final judgeship recommendation for approval by the Committee on Judicial Resources. The committee's recommendation is then provided to the Judicial Conference for final approval (prior to being transmitted to Congress). This multistep evaluation and recommendation process is used for each court that submitted a new judgeship request to the subcommittee.

Factors Used to Evaluate the Need for New Judgeships

In evaluating a court's judgeship request the Judicial Conference examines whether certain caseload levels have been met, as well as court-specific information that might uniquely affect the court making the request.

Filings per Authorized Judgeship

The caseload levels of the courts determine the standards by which the Judicial Conference begins to consider any requests for additional judgeships.42 The caseload level of a court is expressed as filings per authorized judgeship, assuming all vacancies on the court are filled.

The specific measure or statistic related to case filings that the Judicial Conference examines for U.S. circuit courts is called adjusted filings per panel.43 The standard used by the Judicial Conference as its starting point for evaluating any judgeship request by a circuit court is 500 adjusted filings per panel (based on authorized judgeships).

The specific measure related to case filings that the Judicial Conference examines for U.S. district courts is called weighted filings per authorized judgeship.44 The standard used by the Judicial Conference as its starting point for evaluating any judgeship request by a district court is 430 weighted filings per authorized judgeship after accounting for any additional judgeships that would be recommended by the Conference.

For smaller district courts, however, with fewer than 5 authorized judgeships, the standard used is current weighted filings above 500 per judgeship (since accounting for any new judgeships in the calculation would often reduce, for these smaller courts, the weighted filings per authorized judgeship below the 430 level).45

Other Considerations

While caseload statistics are important in evaluating a court's request for additional judgeships, the Judicial Conference also considers court-specific information that might affect the judgeship needs of a particular court. According to the Administrative Office of U.S. Courts, "other factors are also considered that would make a court's situation unique and provide support either for or against a recommendation for additional judgeships."46 These factors include the availability of senior, visiting, and magistrate judges to provide assistance;47 geographic factors; unusual caseload activity; temporary increases or decreases in a court's workload; and any other factors that an individual court highlights as important in the evaluation of its judgeship needs.

Most Recent Recommendations for New Judgeships (116th Congress)

The Judicial Conference's most recent recommendations to Congress for new circuit and district court judgeships were made in March 2019. The Conference recommended that Congress authorize 5 new circuit court judgeships and 65 new permanent district court judgeships (as well as convert 8 existing temporary district court judgeships to permanent status).

Judicial Circuits Recommended for New Judgeships

The Judicial Conference recommended that Congress establish five new judgeships for the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit given its "consistently high level of adjusted filings [per three-judge panel]" and the court's "heavy pending caseload."48

In June 2018, the Ninth Circuit had 740 adjusted filings per panel (the third highest among the 11 regional circuits).49

Congressional authorization of 5 additional judgeships for the Ninth Circuit would increase the number of authorized judgeships for the circuit from 29 to 3450 and increase the total number of circuit court judgeships, nationally, from 179 to 184.

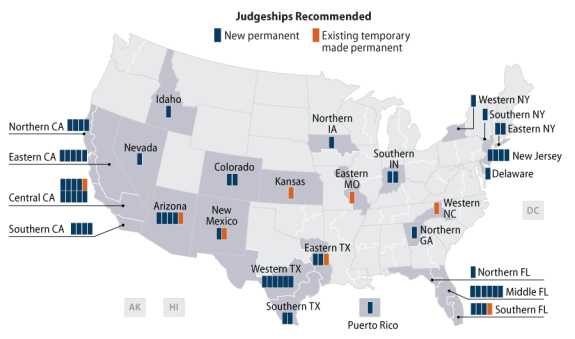

Judicial Districts Recommended for New Judgeships

The Judicial Conference recommended that Congress establish 65 new judgeships for 27 judicial districts51 (with more than one judgeship recommended for some districts) and convert 8 temporary district court judgeships to permanent positions.

Figure 2 shows the 27 judicial districts for which the Conference has recommended new judgeships. Of the 27 districts, the Conference recommended the creation of more than one new judgeship in 15 (or 56% of districts). The greatest number of new judgeships, 10, was recommended for the Central District of California (composed of Los Angeles County and six other counties).52 The Central District of California is the most populous judicial district in the country, with a population of nearly 19.5 million.53

Of the 73 new district court judgeships recommended by the Judicial Conference (which includes converting 8 temporary judgeships to permanent positions), 45 (or 62%) are recommended for district courts located in the country's three most populous states—California, Texas, and Florida. Of the 45 judgeships, 23 are recommended for district courts in California, 11 for courts in Texas, and 11 for courts in Florida.

Altogether, there are 10 new judgeships recommended for district courts located in four southwestern states (Arizona, Colorado, Nevada, and New Mexico). There are also nine new judgeships recommended for district courts located in three northeastern states (Delaware, New Jersey, and New York). The remaining nine judgeships are recommended for courts located in other states.

Many of the U.S. district courts recommended to receive new judgeships hold court in some of the nation's most populous cities—including, but not limited to, Dallas (Northern District of Texas); Houston (Southern District of Texas); Jacksonville (Middle District of Florida); Los Angeles (Central District of California); New York City (Southern District of New York); Phoenix (District of Arizona); San Antonio (Western District of Texas); San Diego (Southern District of California); San Francisco (Northern District of California); and San Jose (Northern District of California).54

U.S. District Courts Identified as Having Urgent Need for New Judgeships

During the Judicial Conference's March 2011 proceedings, the Conference authorized the Director of the Administrative Office of U.S. Courts to pursue separate congressional legislation for Conference-approved additional judgeships for certain district courts meeting a designated threshold of weighted filings. The purpose of such a policy change was to enable the Director "to focus Congress' attention on those courts determined to have the greatest need based on specific parameters."55

The Conference's most recent recommendations identified six district courts with an urgent need for new judgeships, stating that these particular courts "continue to struggle with extraordinarily high and sustained workloads."56 These district courts include the Western District of Texas,57 Eastern District of California,58 Southern District of Florida,59 Southern District of Indiana,60 and the Districts of New Jersey61 and Delaware.62

The "severity of conditions"63 in these districts, according to the Conference, "require immediate action."64 Consequently, the Conference urged Congress "to establish, as soon as possible, new judgeships in those districts."65

The Conference's final judgeship recommendations describe select caseload statistics for each of these six district courts.66 These descriptions, provided in part below, are based upon the biennial survey process conducted by the Conference's Subcommittee on Judicial Statistics.

The Conference's recommendations, quoted at length below, note the change in different types of filings that occurred between September 2017 and June 2018. The September 2017 date was used as the "cut-off date" by the subcommittee to make its initial judgeship recommendations (it was the most recent date for which the subcommittee had caseload data prior to the start of the survey process). The June 2018 reporting date was used by the subcommittee to make its final judgeship recommendations (it was the most recent date for which the Conference had caseload data available prior to submitting its recommendations to Congress).

- Western District of Texas. From September 2017 to June 2018, overall filings in the court increased by 13% "due to an increase in criminal felony filings. Criminal filings rose 28 percent due to a 48 percent increase in immigration filings. The increase was partially offset by moderate declines in drug and fraud prosecutions. Criminal filings are now the highest in the nation at 644 per judgeship. The number of civil cases filed fell three percent as declines in prisoner petitions and private contract litigation more than offset increases in tort actions, copyright litigation, and patent filings."67 The Conference also notes that the number of supervised release hearings declined 11% but is currently more than twice the national average at 109 per judgeship.68

- Eastern District of California. The "number of civil cases filed [excluding contract actions related to a multidistrict litigation action] rose four percent as cases related to the Fair Debt Collection Practices Act more than doubled and prisoner petitions rose substantially, more than offsetting a decline in real property litigation. Civil filings continue to exceed 700 per judgeship, among the highest in the nation [even if the multidistrict litigation action is excluded]. The number of criminal felony filings rose 12 percent as a result of increases in most types of offenses, the largest of which occurred in firearms prosecutions."69 The Conference also notes that criminal filings in the Eastern District of California, at 99 per judgeship, remain below the national average.70

- Southern District of Florida. The overall filings in the district "rose two percent due to moderate increases in both civil and criminal filings. The number of civil cases filed rose three percent as increases in insurance contract cases, torts filings, and civil rights litigations were partially offset by declines in Fair Labor Standards Act cases, prisoner petitions, cases related to the Fair Debt Collection Practices Act, and social security appeals....The number of criminal felony filings increased two percent as increases in most offense types, the largest of which occurred in fraud prosecutions, more than offset" a decline in drug, burglary, larceny, and theft filings.71 The Conference also notes that the district court's pending caseload "remains substantially below the national average."72

- Southern District of Indiana. Since September 2017, "the court experienced an influx of over 2,200 personal injury product liability filings related to a multidistrict litigation (MDL) action in which the district serves as the transferee court.73 Apart from these cases, overall filings fell two percent as a decline in civil filings was partially offset by an increase in criminal filings. The number of civil cases filed decreased four percent as declines in social security appeals, civil rights cases, and federal prisoner petitions were partially offset by an increase in state prisoner petitions. The number of criminal felony filings rose 16 percent due almost entirely to a 63 percent rise in firearms prosecutions."74 The Conference also notes, however, that criminal filings in the Southern District of Indiana, at 108 per judgeship, remain "slightly below" the national average.75

- District of New Jersey. Excluding certain types of cases,76 "overall filings rose 10 percent due to increases in both civil and criminal felony filings. The number of civil cases filed ... also rose 10 percent due primarily to increases in copyright litigation, civil rights actions, ERISA filings, land condemnation cases, and social security appeals. A 27 percent increase in criminal filings results from higher number of firearms, drug, fraud, and immigration prosecutions."77 Additionally, the pending caseload for the court "nearly doubled as a result of the influx of personal injury product liability cases."78 The Judicial Conference also notes that "despite the increase, criminal filings are among the lowest in the nation at 36 per judgeship."79

- District of Delaware. From September 2017 to June 2018, "overall filings rose seven percent due to an increase in civil filings. The number of civil cases filed rose eight percent due almost entirely to a 20 percent increase in patent litigation. The court has the highest number of patent filings in the nation, which have risen substantially since the Supreme Court's May 2017 decision in TC Heartland LLC v. Kraft Foods Group Brands LLC, which modified the venue standards for patent infringement lawsuits.... Civil filings are now well above the national average at 518 per judgeship."80 In contrast, the "number of criminal felony filings declined ... as filings of all offense types remained relatively stable."81 Additionally, in its recommendation, the Judicial Conference states that criminal filings in the District of Delaware "are the 2nd lowest in the nation at 21 per judgeship."82

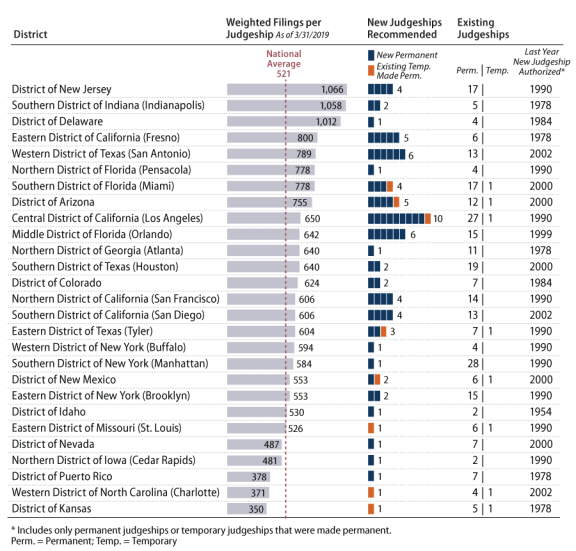

Weighted Case Filings of Judicial Districts Recommended for New Judgeships

As discussed above, the specific statistic used by the Judicial Conference to compare caseloads across U.S. district courts is the number of weighted filings per authorized judgeship for each court. Figure 3 shows the number of weighted filings per judgeship for each of the 27 district courts included in the Conference's most recent recommendation to Congress.83

The national average of 521 weighted filings per authorized judgeship is shown by the reference line in the figure. For the 27 district courts where the Judicial Conference recommends additional judgeships (including conversion of existing temporary judgeships to permanent status), weighted filings averaged 646 per authorized judgeship.

Of the 27 district courts recommended to receive additional judgeships, 5 courts have caseloads that fall below 500 weighted filings per authorized judgeship; 6 have 500 to 599 weighted filings; 8 courts have 600 to 699 weighted filings; 4 courts have 700 to 799 weighted filings; 1 court has 800 weighted filings; and 3 courts have more than 1,000 weighted filings.

The five districts listed in Figure 3 with the greatest number of weighted filings are among the six U.S. district courts discussed above as having the most urgent need for additional judgeships (the remaining district, the Southern District of Florida, has the seventh-highest number of weighted filings).

A plurality of the U.S. district courts listed in Figure 3 last had a permanent judgeship authorized in 1990 (10 of 27, or 37%). Another 8 district courts last had a permanent judgeship authorized prior to 1990 (2 in 1984, 5 in 1978, and 1 in 1954).84 And 9 district courts last had a permanent judgeship authorized after 1990 (1 in 1999, 5 in 2000, and 3 in 2002).

Several of the courts listed in the figure have weighted filings that fall below the national average (521 weighted filings per judgeship), including the District of Nevada, Northern District of Iowa (Cedar Rapids), District of Puerto Rico, Western District of North Carolina (Charlotte), and the District of Kansas.

As noted previously, a court's caseload is not the only factor the Judicial Conference considers in evaluating a court's judgeship needs. Consequently, the Conference's recommendations can be based, in part, on additional factors. For example, in its evaluation of the judgeship needs for districts where weighted filings are below the national average, the Conference identifies various reasons why it recommends additional judgeships. Some of the reasons include a substantial decline in senior judge assistance in handling cases, the geographic challenges associated with managing workload imbalances between different courthouses in the district, a high pending caseload relative to other district courts in the nation, and a number of criminal filings that is well above the national average.85

Options for Congress

As discussed above, Congress determines through legislative action the size of the federal judiciary. Consequently, creating additional U.S. circuit and district court judgeships requires congressional authorization of such judgeships. Such authorization can be accomplished by passing legislation devoted solely to judgeships (i.e., "omnibus judgeships bills") or by including the authorization in an appropriations bill or other legislative vehicle.

Congress may decide not to authorize additional circuit and district court judgeships. If Congress were to authorize such judgeships, it has several options available to it. These include (but are not limited to) the following:

- Adopting all of the most recent recommendations of the Judicial Conference by creating 5 additional permanent judgeships for the Ninth Circuit and 65 additional permanent judgeships for the district courts specified by the Conference (as well as converting 8 temporary district court judgeships to permanent status).

- Adopting, in part, the recommendations of the Judicial Conference by creating additional permanent circuit and/or district court judgeships for some of the courts identified by the Conference's biennial review process as needing additional judgeships.

- Adopting, in part, the Conference's recommendations by authorizing new judgeships only for the six U.S. district courts identified by the Conference as having the most urgent need for such judgeships. It might also include only adopting the Conference's recommendations for converting eight temporary judgeships to permanent status. As presented in Table 1, each of the current temporary judgeships is set to lapse in 2020 if not further extended or made permanent by Congress.

- Authorizing new judgeships for circuit and/or district courts that were not recommended for additional judgeships by the Judicial Conference (such judgeships might be permanent or temporary). Congress might conclude on the basis of its own review that there is a need for such judgeships in other courts not included in the Conference's most recent recommendations. For example, the Judicial Conference only assesses a circuit court's need for additional judgeships if at least a majority of active judges serving on the court approve of a request for additional judgeships. Congress may nonetheless decide to authorize additional judgeships for circuit courts where this threshold has not been met.

- Authorizing new judgeships for some of the courts recommended by the Judicial Conference as needing new judgeships, as well as authorizing new judgeships for other courts not included in the Conference's most recent recommendations.