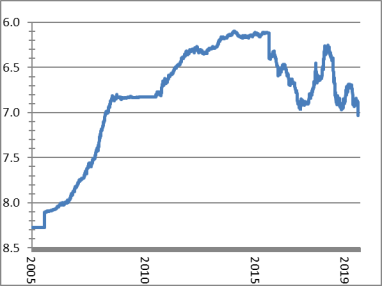

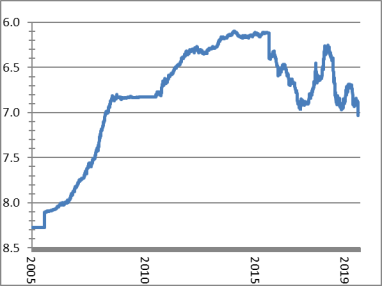

Figure 1. Chinese Yuan per U.S. Dollar

Source: International Monetary Fund

Notes: A decrease in the graph represents a depreciation of the Chinese yuan relative to the U.S. dollar.

On August 4, China's central bank allowed its currency, the yuan, to depreciate to an 11-year low, breaking the politically sensitive threshold of seven yuan to one U.S. dollar (Figure 1). A depreciation of the yuan against the U.S. dollar makes Chinese exports less expensive in global markets. Some analysts speculate the depreciation is designed to offset and retaliate against U.S. tariffs on Chinese imports, coming four days after President Trump announced his intent to impose an additional 10% tariff on $300 billion of Chinese imports on September 1. There are differing views on the causes of yuan's movements, however, as discussed below.

On August 5, Treasury Secretary Mnuchin, under the auspices of President Trump, determined that China is manipulating its currency. Although some policymakers have called for this designation for years and Donald Trump made it a central issue in his presidential campaign, the Treasury Department had not labeled a country as a currency manipulator in 25 years.

|

Figure 1. Chinese Yuan per U.S. Dollar |

|

|

Source: International Monetary Fund Notes: A decrease in the graph represents a depreciation of the Chinese yuan relative to the U.S. dollar. |

The Treasury Secretary designated China as a currency manipulator under the provisions laid out in the Omnibus Trade and Competitiveness Act of 1988 (the 1988 Trade Act, P.L. 100-418, 22 U.S.C. 5301-5306). This law requires the Treasury Department to analyze on an annual basis the exchange rate policies of foreign countries, in consultation with the International Monetary Fund (IMF), and "consider whether countries manipulate the rate of exchange between their currency and the United States dollar for purposes of preventing effective balance of payments adjustments or gaining unfair competitive advantage in international trade."

If manipulation is occurring with respect to countries that have global currency account surpluses and significant bilateral trade surpluses with the United States, the Secretary of the Treasury is to initiate negotiations, in consultation with the IMF, to ensure adjustment in the exchange rate and eliminate the unfair trade advantage. The Treasury Secretary is not required to start negotiations in cases where they would have a serious detrimental impact on vital U.S. economic and security interests.

The Treasury Department had previously designated China, as well as Taiwan and South Korea, as currency manipulators in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

The Treasury Secretary has not found China to be manipulating its currency under a second set of provisions in U.S. law, enacted more recently through the Trade Facilitation and Trade Enforcement Act of 2015 (P.L. 114-125; 19 U.S.C. 4421-4422). This act addressed some policymakers' concerns that successive Administrations had taken insufficient action to address currency manipulation under the 1988 Trade Act. According to the newer provisions, if a country meets three criteria—significant bilateral trade surplus with the United States, material currency account surplus, and engaged in persistent one-sided interventions in foreign exchange markets—the Treasury Secretary is required to engage bilaterally with the country and if the problem persists, take specified putative actions.

China does not meet the three specified criteria, according to the May 2019 assessment by the Treasury Department. China has a large trade imbalance with the United States (goods trade surplus of $419 billion in 2018), but a small current account surplus (0.4% of GDP in 2018) and only "modest" interventions in foreign exchange markets.