Under the Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act (OCSLA), as amended,1 the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) must prepare and maintain forward-looking five-year plans—referred to by BOEM as five-year programs—for proposed public oil and gas lease sales on the U.S. outer continental shelf (OCS). On January 4, 2018, BOEM released a draft proposed program (DPP) for the period from late 2019 through mid-2024.2 The DPP proposes 47 lease sales during the five-year period: 12 in the Gulf of Mexico region, 19 in the Alaska region, 9 in the Atlantic region, and 7 in the Pacific region.3 The DPP would make available for leasing more than 90% of the total OCS acreage.4

BOEM's development of a five-year program typically takes place over two or three years, during which successive drafts of the program are published for review and comment. All available leasing areas are initially examined, and the selection may then be narrowed based on economic and environmental analysis, including environmental review under the National Environmental Policy Act,5 to arrive at a final leasing schedule. Because the program is developed through a winnowing process, the final program may remove sales proposed in earlier drafts but will not include any new sales. At the end of the process, the Secretary of the Interior must submit each program to the President and to Congress for a period of at least 60 days, after which the proposal may be approved by the Secretary and may take effect with no further regulatory or legislative action.

Currently, offshore leasing is taking place under a program for mid-2017 through mid-2022 developed under the Obama Administration.6 The Trump Administration's draft program would replace the final years of the current program.7 The 2017-2022 program scheduled 11 OCS lease sales during the five-year period: 10 in the Gulf of Mexico region (occurring twice each year, starting in 2017), 1 in the Cook Inlet planning area of the Alaska region (scheduled for 2021), and none in the Atlantic or Pacific regions.

The leasing decisions in BOEM's five-year programs may affect the economy and environment of individual coastal states and of the nation as a whole. Accordingly, Congress typically has been actively involved in planning and oversight of the five-year programs. The following discussion summarizes recent developments related to the leasing program and analyzes selected congressional issues and actions. The history, legal and economic framework, and process for developing the programs are discussed in CRS Report R44504, The Bureau of Ocean Energy Management's Five-Year Program for Offshore Oil and Gas Leasing: History and Final Program for 2017-2022.

The 116th Congress could influence the five-year program (either the 2017-2022 program currently in force or the new program under development) through oversight or by enacting legislation with requirements for the program. For example, Members could enact legislation to add new sales to the program, to remove scheduled sales, or to change the terms of program development under the OCSLA. Some bills have sought to prohibit the Trump Administration from replacing the final years of the 2017-2022 program with a new program for 2019-2024. Congress also could impose leasing moratoria on new areas or, alternatively, could end existing moratoria imposed by Congress or the President and mandate lease sales in these previously unavailable areas.

Recent Developments

BOEM released the DPP for 2019-2024 on January 4, 2018, with a 60-day comment period that ended on March 9, 2018.8 BOEM received more than 2 million comments on the DPP.9 BOEM had announced its intent to publish its second draft of the program—known as the proposed program, or PP—toward the end of 2018 or early in 2019, with the aim of having the final version approved by the end of 2019.10 However, this timetable was influenced by a recent court decision. In March 2019, the U.S. District Court for the District of Alaska vacated portions of an executive order issued by President Trump in 2017,11 which had opened certain parts of the Arctic and Atlantic Oceans to consideration for oil and gas leasing, effectively revoking withdrawals of these areas made previously by President Obama under Section 12(a) of OCSLA.12 The court decision means that President Obama's withdrawals of these areas from leasing consideration remain in force, which affects the 2019-2024 DPP, in that the DPP had proposed scheduling lease sales in these areas. The Secretary of the Interior has stated that publication of the 2019-2024 PP will be delayed while the Administration considers its response to the court decision.13

Lease sales continue under the current (2017-2022) leasing program. Four of the program's 11 scheduled lease sales had been held as of July 2019, all in the Gulf of Mexico. These sales implement the Obama Administration's shift to a region-wide lease sale approach for the 2017-2022 program, offering available blocks in all three Gulf planning areas combined (unlike previous Gulf lease sales, which focused on a particular planning area—either the Western, Central, or Eastern Gulf).14 The 2017-2022 program shifted to this region-wide approach partly to increase flexibility for companies that also are bidding on lease blocks in Mexican Gulf waters. This region-wide approach is also continued in the Trump Administration's proposal for 2019-2024.15

Selected Issues for Congress

Under the OCSLA, BOEM must take into account economic, social, and environmental values in making its leasing decisions.16 BOEM's assessments of the appropriate balance of these factors for leasing in the four OCS regions—the Atlantic, Pacific, Alaska, and Gulf of Mexico regions—are matters for debate in Congress and elsewhere in the nation. Congress has debated both the 2017-2022 program approved by the Obama Administration and the 2019-2024 DPP proposed by the Trump Administration, and it has considered potential alterations to both programs.

The 2019-2024 DPP would make available nearly all of the OCS for oil and gas leasing, except for areas that BOEM is statutorily prohibited from leasing.17 Because the leasing program proceeds through a winnowing process, the Administration could end up removing some sales proposed in the DPP from later versions of the program.18 Congressional debate on the program has focused particularly on the Administration's proposals for lease sales in parts of the OCS where new leasing has not occurred for many years, including the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans and the Eastern Gulf of Mexico. Also debated are the total number of sales and acres offered under the program.

Total Sales and Acreage Available for Leasing

The 2019-2024 DPP would make available more than 90% of the total OCS acreage and more than 98% of undiscovered, technically recoverable oil and gas resources in federal offshore areas, according to the Department of the Interior.19 The program proposes 47 lease sales during the five-year period, including 12 sales in the Gulf of Mexico region, 19 in the Alaska region, 9 in the Atlantic region, and 7 in the Pacific region. If all of the lease sales in the DPP were included in the final program, this would be more lease sales than have been scheduled for any previous five-year program.20 (However, as discussed, the program development process typically has involved a narrowing of sales in successive drafts, based on economic and environmental reviews.) BOEM states in the DPP that its inclusive leasing strategy aims to implement President Trump's "America-First" offshore energy strategy, outlined in his April 2017 executive order, and that the proposed program would help to "mov[e] the United States from simply aspiring for energy independence to attaining energy dominance."21

By contrast, the 2017-2022 program currently in force, which was developed by the Obama Administration, made available for leasing less than 6% of total acreage on the U.S. OCS, although this area included nearly half of all undiscovered technically recoverable oil and gas resources estimated to exist on the OCS, according to program documents.22 The final 2017-2022 program was the result of a winnowing process; the DPP for the 2017-2022 program had contained 14 proposed sales, which would have made available nearly 80% of undiscovered technically recoverable resources, according to BOEM.23

The acreage available for leasing and the overall number of sales have been controversial for both programs. Some Members of Congress, industry representatives, and others contended that the 2017-2022 program was overly restrictive compared with earlier programs and that it would limit job creation and economic growth.24 These stakeholders have supported the broader scope proposed by the Trump Administration for the 2019-2024 program. Others express that the Obama Administration's leasing schedule reflected an appropriate balance of economic, environmental, and social considerations, and they oppose the expanded leasing proposals in the 2019-2024 DPP, especially for areas where leasing has not occurred in recent years. Still others, including some environmental groups, advocate for less offshore oil and gas leasing than is provided for under either program, citing concerns about the climate change implications of offshore oil and gas development and the possibility of environmental damage from a catastrophic oil spill, such as the spill that took place in 2010 on the Deepwater Horizon oil platform in the Gulf of Mexico.25

Gulf of Mexico Region

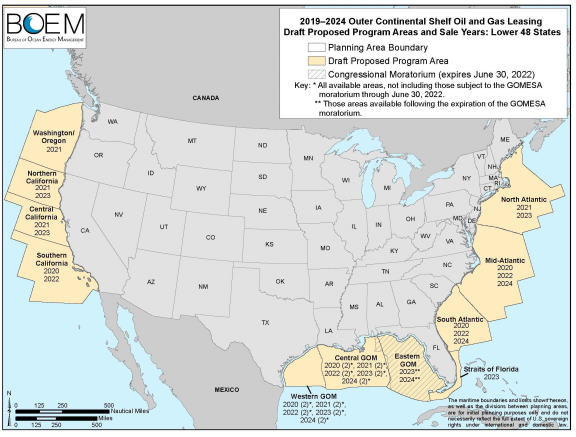

Almost all U.S. offshore oil and gas production currently takes place in the Gulf of Mexico.26 The Gulf has the most mature oil and gas development infrastructure of the four planning regions, as well as the highest resource potential, according to BOEM estimates.27 The lease schedules promulgated by the Trump and Obama Administrations are more similar for the Gulf than for the other regions, in that both programs would make available all unleased Gulf acreage that is not prohibited from leasing. The 2017-2022 program had scheduled two region-wide lease sales for the Gulf for each year. The 2019-2024 DPP proposes two region-wide lease sales each year for 2019-2022, and would add a third sale specifically for the Eastern and Central Gulf of Mexico in 2023 and 2024 (Figure 1).28

A contentious issue in the region is leasing in the Eastern Gulf close to the state of Florida. Under the Gulf of Mexico Energy Security Act of 2006 (GOMESA), offshore leasing is prohibited through June 2022 in a defined area of the Gulf off the Florida coast.29 Some Members of Congress and other stakeholders wish to extend this prohibition or make it permanent. They contend that leasing in Gulf waters around Florida could potentially damage the state's beaches and fisheries, which support strong tourism and fishing industries, and could jeopardize mission-critical defense activities such as those at Pensacola's Eglin Air Force Base. By contrast, others advocate for shrinking the area covered by the ban or eliminating the ban before its scheduled expiration date. They emphasize the economic significance of oil and gas resources off the Florida coast and contend that development would create jobs, strengthen the state and national economies, and contribute to U.S. energy security. The 2019-2024 DPP proposes lease sales in the area currently covered by the moratorium, with the sales scheduled after the moratorium expires.

|

Figure 1. BOEM's Proposed Program Areas for Offshore Oil and Gas Leasing in the Gulf of Mexico, Atlantic, and Pacific Regions (2019-2024 DPP) |

|

|

Source: 2019-2024 DPP, at https://www.boem.gov/NP-DPP-Map-Lower-48-States/. |

Alaska Region

Congressional debate has been intense over offshore leasing in the Alaska region. Interest in exploring for offshore oil and gas in the region has grown as decreases in the areal extent of summer polar ice make feasible a longer drilling season. Estimates of substantial undiscovered oil and gas resources in Arctic waters also have contributed to the increased interest.30 However, the region's severe weather and perennial sea ice, and its relative lack of infrastructure to extract and transport offshore oil and gas, continue to pose technical and financial challenges to new exploration. Low energy prices, such as those currently being experienced, diminish the short-term incentives for development in the region, because Alaskan production is relatively costly. Among Alaska's 15 BOEM planning areas, the Beaufort and Chukchi Seas are the only two areas with existing federal leases, and only the Beaufort Sea has any producing wells in federal waters (from a joint federal-state unit). Stakeholders including the state of Alaska and some Members of Congress seek to expand offshore oil and gas activities in the region. Other Members of Congress and many environmental groups oppose offshore oil and gas drilling in the Arctic, due to concerns about potential oil spills and about the possible contributions of these activities to climate change.

The Obama Administration had at times expressed support for expanding offshore exploration in the Alaska region, while also pursuing safety regulations that aimed to minimize the potential for oil spills.31 The Obama Administration's originally proposed program for 2017-2022 included three Alaska sales—one each in the Beaufort Sea, Chukchi Sea, and Cook Inlet Planning Areas. However, for the final program, the Administration removed the sales for the Beaufort and Chukchi Seas and retained only the sale for Cook Inlet, citing reasons for the removal that included "opportunities for exploration and development on [already] existing leases, the unique nature of the Arctic ecosystem, recent demonstration of constrained industry interest in undertaking the financial risks that Arctic exploration and development present, current market conditions, and sufficient existing domestic energy sources already online or newly accessible."32 Further, in December 2016, President Obama withdrew much of the U.S. Arctic from leasing disposition for an indefinite time period.33

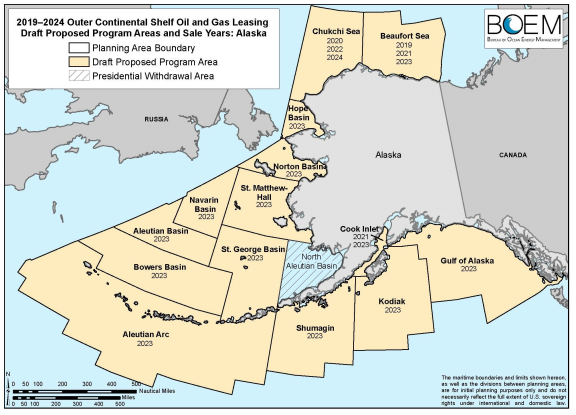

In April 2017, President Trump's executive order on offshore energy strategy modified President Obama's withdrawals and opened all Alaska region areas for consideration in a revised leasing program, except for the North Aleutian Basin.34 The 2019-2024 DPP scheduled lease sales in all of the available areas (Figure 2). Two sales are proposed for Cook Inlet, and three sales each are proposed for the Beaufort and Chukchi Seas, which are the two planning areas with the highest estimated resource potential in the region and are thus a focus of industry interest. (Industry interest in some of the other planning areas may be lower, as many are thought to have relatively low or negligible petroleum potential.) However, the proposed lease sales in the Beaufort and Chukchi Seas would be affected by the March 2019 court decision discussed above (under "Recent Developments"), which vacated President Trump's executive order opening these areas for leasing. The decision means that President Obama's withdrawals of large portions of these areas from leasing consideration remain in force.

|

Figure 2. BOEM's Proposed Program Areas for Offshore Oil and Gas Leasing in Alaska (2019-2024 DPP) |

|

|

Source: BOEM, 2019-2024 DPP, at https://www.boem.gov/NP-DPP-Map-Alaska/. Note: "Presidential Withdrawal Area" does not include areas modified from withdrawal status by President Trump in Executive Order 13795 of April 2017. For legal issues concerning the modification, see CRS Legal Sidebar WSLG1799, Trump's Executive Order on Offshore Energy: Can a Withdrawal be Withdrawn?, by Adam Vann. |

Supporters of increased offshore leasing in the Alaska region contend that growth in offshore oil and gas development is critical for Alaska's economic health as the state's onshore oil fields mature.35 They further assert that Arctic offshore energy development will play a growing role nationally by reducing U.S. dependence on oil and gas imports and allowing the United States to remain competitive with other nations, including Russia and China, that are pursuing economic interests in the Arctic. These stakeholders contend that Arctic offshore activities can be conducted safely, and point to a history of successful well drilling in the Beaufort and Chukchi Seas in the 1980s and 1990s.

Those who favor few or no Alaska offshore lease sales, by contrast, are concerned that it would be challenging to respond to a major oil spill in the region, because of the icy conditions and lack of spill-response infrastructure.36 The Obama Administration's Arctic regulations focused on ways in which companies would need to compensate for the lack of spill-response infrastructure, such as by having a separate rig available at drill sites to drill a relief well in case of a loss of well control.37 Opponents of Arctic leasing also are concerned that it represents a long-term investment in oil and gas as an energy source, which could slow national efforts to address climate change. They contend, too, that new leasing opportunities in the region are unnecessary, since industry has pulled back on investing in the Arctic in the current period of relatively low oil prices.38 Others assert, however, that tepid industry interest in the region is due more to the overly demanding federal regulatory environment than to market conditions.

Among those favoring expanded leasing in the region are some Alaska Native communities, who see offshore development as a source of jobs and investment in localities that are struggling financially. Other Alaska Native communities have opposed offshore leasing in the region, citing concerns about environmental threats to subsistence lifestyles. Alaska Governor Bill Walker submitted comments for the 2019-2024 DPP supporting the proposed sales in Cook Inlet and the Beaufort and Chukchi Seas but opposing sales in the other Alaska planning areas.39

Atlantic Region

The 2019-2024 DPP proposes nine lease sales for the Atlantic region, including sales in all Atlantic region planning areas (Figure 1). If conducted, they would be the first offshore Atlantic oil and gas lease sales since 1983. The lack of oil and gas activity in the Atlantic region in the past 30 years was due in part to congressional bans on Atlantic leasing imposed in annual Interior appropriations acts from FY1983 to FY2008, along with presidential moratoria on offshore leasing in the region during those years. Starting with FY2009, Congress no longer included an Atlantic leasing moratorium in annual appropriations acts. In 2008, President George W. Bush also removed the long-standing administrative withdrawal for the region.40 These changes meant that lease sales could potentially be conducted for the Atlantic. However, no Atlantic lease sale has taken place in the intervening years.41

The Atlantic states, and stakeholders within each state, disagree about whether oil and gas drilling should occur in the Atlantic.42 Supporters contend that oil and gas development in the region would lower energy costs for regional consumers, bring jobs and economic investment, and strengthen U.S. energy security. Opponents express concerns that oil and gas development would undermine national clean energy goals and that oil spills could threaten coastal communities. Also of concern for leasing opponents is the potential for oil and gas activities to damage the tourism and fishing industries in the Atlantic region and to conflict with military and space-related activities of the Department of Defense (DOD) and National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA).

|

Geological and Geophysical (G&G) Activities in the Atlantic Ocean A complicating factor in considering oil and gas leasing in the Atlantic Ocean is uncertainty about the extent and location of hydrocarbon resources. Given congressional and administrative moratoria on Atlantic leasing activities for most of the past 30 years, no recent geological and geophysical (G&G) surveys of the region's offshore resources have been conducted. Previous seismic surveys, dating from the 1970s, used older technologies that are considered less precise than recent methods. The Obama Administration issued a record of decision (ROD) in July 2014 to allow new G&G surveys. However, in January 2017, the Obama Administration denied applications from companies to conduct Atlantic surveys under the ROD, citing among other reasons a diminished need for the information because no Atlantic lease sales were included in the 2017-2022 program. In April 2017, President Trump's executive order on offshore energy ordered the agencies to expedite seismic survey permits, and BOEM subsequently announced that it would resume evaluations of the G&G permit applications. BOEM continues to review the permits. The National Marine Fisheries Service issued incidental harassment authorizations as part of the permit approval process, which have been the subject of a lawsuit by some conservation groups and state of the South Carolina. The G&G permitting decisions are separate from the five-year program, which is specifically concerned with lease sales. The House Natural Resources Committee has held oversight hearings related to Atlantic G&G testing, most recently in March 2019. In such hearings, some Members have expressed support for expediting the permit-review process and others have opposed letting G&G testing go forward. Witnesses have differed in their evaluations of the potential harm to Atlantic marine mammals from seismic activities. BOEM included measures to mitigate the impacts of G&G activities on marine life in its ROD, but some have argued that the measures are inadequate. Some recent legislation (e.g., H.R. 1149 in the 116th Congress) would prohibit seismic surveys in the Atlantic region, while other legislation (e.g., H.R. 3133 in the 115th Congress) has sought to expedite permitting for seismic surveys. |

In draft versions of the 2017-2022 program, the Obama Administration had proposed a lease sale in a combined portion of the Mid- and South Atlantic planning areas. However, after further analysis, the Obama Administration removed the Atlantic sale, citing "strong local opposition, conflicts with other ocean uses, ... [and] careful consideration of the comments received from Governors of affected states."43 The Obama Administration also stated that, given growth over the past decade in onshore energy development, "domestic oil and gas production will remain strong without the additional production from a potential lease sale in the Atlantic."44 The Obama Administration's proposal had included a 50-mile buffer zone off the coast where leasing would not take place, in order to reduce conflicts with other uses of the OCS, including DOD and NASA activities. However, on further analysis, the Administration assessed that the areas of DOD and NASA concern "significantly overlap the known geological plays and available resources," which contributed to its decision to remove the Atlantic sale altogether from the final program.45

For the 2019-2024 DPP, BOEM scheduled lease sales in all of the Atlantic region planning areas. BOEM considered a leasing option with a coastal buffer to accommodate military use concerns but did not choose this option for the DPP.46 BOEM stated that this and other program options may be further analyzed in subsequent versions of the program.47

Pacific Region

The 2019-2024 DPP proposes seven lease sales in the Pacific region, including sales in all of the region's planning areas (Figure 1). No federal oil and gas lease sales have been held for the Pacific since 1984, although active leases with production remain in the Southern California planning area.48 Like the Atlantic region, the Pacific region was subject to congressional and presidential leasing moratoria for most of the past 30 years.49 These restrictions were lifted in FY2009, but no lease sales were proposed or scheduled for the Pacific region during the Obama Administration. The governors of California, Oregon, and Washington have expressed their opposition to new offshore oil and gas leasing in the region.50 (Administratively, the Pacific region also includes the state of Hawaii, but Hawaii is not part of the oil and gas leasing program because hydrocarbon resources are not present offshore of the state.)51

Congressional stakeholders disagree over whether leasing should occur in the Pacific. Members of Congress who favor broad leasing across the entire OCS have introduced legislation in previous Congresses that would have required BOEM to hold lease sales in the Pacific region.52 Members concerned about environmental damage from oil and gas activities in the region have introduced legislation that would prohibit Pacific oil and gas leasing.53

Role of Congress

Congress can influence the Administration's development and implementation of a five-year program by submitting public comments during formal comment periods, by evaluating programs in committee oversight hearings, and, more directly, by enacting legislation with program requirements.54 Some Members of Congress have pursued these types of influence with respect to the 2019-2024 program, as well as for the 2017-2022 program. For example, for the 2019-2024 program, Members submitted public comments on both the DPP and a previous request for information (RFI), and the House Natural Resources Committee held a hearing to examine DOI's priorities for the program.55

Congress also has considered directly modifying both programs through legislation. For example, some 115th Congress bills (e.g., H.R. 1756, H.R. 4239, S. 665, S. 883) would have added lease sales to the 2017-2022 program or amended the OCSLA to facilitate additional sales in five-year programs generally (e.g., by making it easier for the Interior Secretary to add new sales to programs or by requiring that the Secretary include in each program unexecuted lease sales from earlier programs). Other legislation (e.g., H.R. 4426 in the 115th Congress) proposed to alter the OCSLA to give greater weight to environmental and wildlife considerations in five-year programs. Some bills have sought to prohibit the Trump Administration from replacing the final years of the 2017-2022 program with the new program for 2019-2024 (e.g., H.R. 2248 and S. 935 in the 115th Congress). Still other bills (e.g., H.R. 205, H.R. 279, H.R. 286, H.R. 287, H.R. 291, H.R. 309, H.R. 310, H.R. 337, H.R. 341, H.R. 1941, H.R. 2352, H.R. 3585, S. 1296, S. 1304, and S. 1318 in the 116th Congress) aim to restrict leasing in the 2019-2024 program and thereafter by establishing new moratoria or extending existing moratoria. Some of these bills would permanently prohibit leasing in large areas, such as throughout the Pacific and Atlantic regions.

Either during or after development of the 2019-2024 program, Congress could affect the program by pursuing bills such as these or other legislation. Alternatively, Congress could choose not to intervene, allowing the new program to proceed as developed by BOEM.