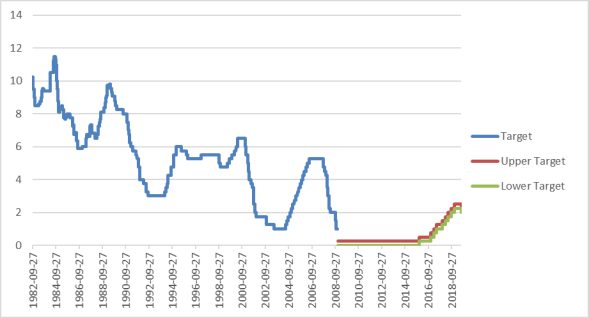

Figure 1. Federal Funds Rate Target

1982-2019

Source: St. Louis Fed, FRED.

Notes: The Fed switched from a point target to a target range in 2008.

On July 31, the Federal Reserve (Fed) reduced the federal funds rate by a quarter of a percentage point. The Fed targets this rate to meet its statutory mandate of maximum employment and stable prices (defined as 2% inflation). Lower interest rates would tend to raise employment and inflation, all else equal.

The Fed typically cuts rates during recessions and raises rates during expansions. Since the Fed began using the federal funds rate as its primary instrument to carry out monetary policy (possibly as early as 1982), it has had four periods of sustained rate reductions (see Figure 1). Three out of four of those episodes coincided with the last three recessions. (The fourth was after the 1981-1982 recession, when the Fed had raised rates to their highest level on record, causing inflation to drop rapidly.) Notably, in all three of those cases, the Fed began to reduce rates 2 months to 12 months before the recession began and continued to reduce or maintain low rates into the beginning of the recovery.

Rates were also briefly cut three other times during these expansions. The 1987-1988 rate reductions were in response to a large drop in the stock market. The Fed justified the 1995-1996 reductions by stating that "as a result of the monetary tightening initiated in early 1994, inflationary pressures have receded enough to accommodate a modest adjustment in monetary conditions." The Fed cut rates in 1998 in response to financial turmoil related to the Russian debt crisis and the failure of a large hedge fund. In hindsight, financial turmoil in 1987 and 1998 did not have a long-lasting effect on financial conditions or the broader economy, but there was considerable fear at the time that they would. The Fed resumed rate increases within about a year of all of these reductions.

The recent rate cut is starting from a lower federal funds rate than any previous cut since 1982. This is in part because the neutral rate that neither stimulates nor restrains economic activity is thought to have fallen. It is also because the Fed never employed contractionary monetary policy in this expansion, unlike at the peak of previous expansions.

|

Figure 1. Federal Funds Rate Target 1982-2019 |

|

|

Source: St. Louis Fed, FRED. Notes: The Fed switched from a point target to a target range in 2008. |

Is the Fed cutting rates to fend off an impending recession? Or is it a temporary blip similar to 1987, 1996, and 1998? Current available data may help answer those questions, with the caveat that the Fed has more up-to-date confidential data that may paint a different picture.

What many find striking about the Fed's decision to cut rates is that the unemployment rate has been at its lowest rate this year since 1969, below the Fed's estimate of the longer-run unemployment rate consistent with maximum employment. Indeed, the unemployment rate is lower today (3.7%) than when the Fed last raised rates in December 2018 (3.9%).

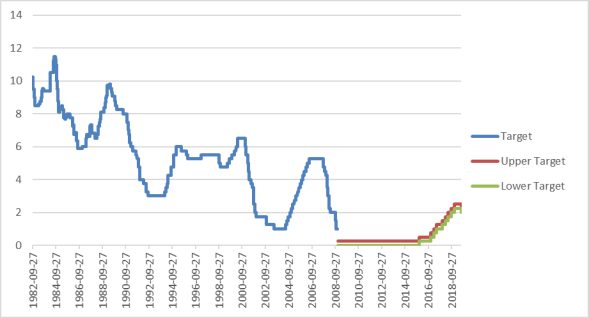

Economic growth slowed from 3.1% in the first quarter of 2019 to 2.1% in the second quarter (see Figure 2). However, at full employment, the economy cannot persistently grow faster than its long-run trend, and the second quarter growth rate is slightly higher than the Fed's projection of longer-run growth and slightly lower than this expansion's average.

|

Figure 2. Quarterly Economic Growth Rates 2009:3-2019:2 |

|

|

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis. Notes: Growth rates are annualized. |

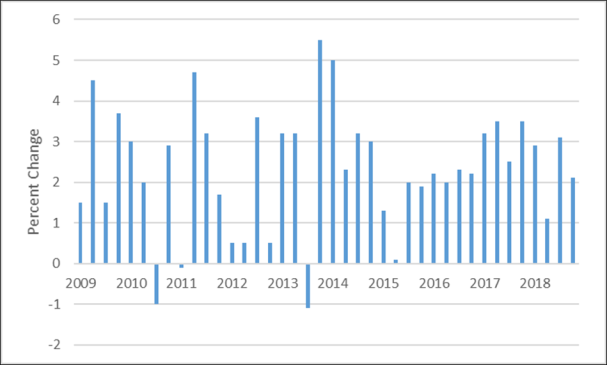

Employment growth also shows no sign of a recession, and only a modest cooling off from 2018 (see Figure 3). Although job growth was relatively weak in May (72,000 jobs added), it was relatively strong in June (224,000) and for 2019 to date (a monthly average of 172,000, compared to 223,000 in 2018). Because jobs data are highly volatile, too much cannot be inferred from a one-month change.

|

Figure 3. Monthly Change in Employment 2010-2019 |

|

|

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics. |

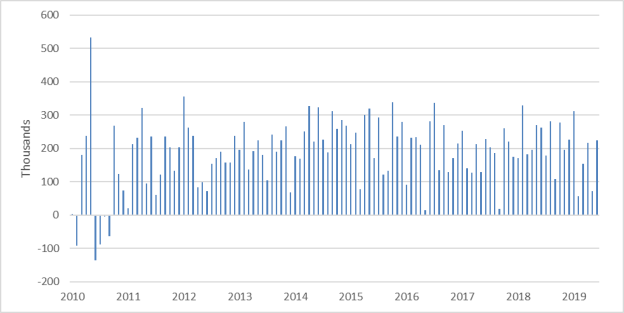

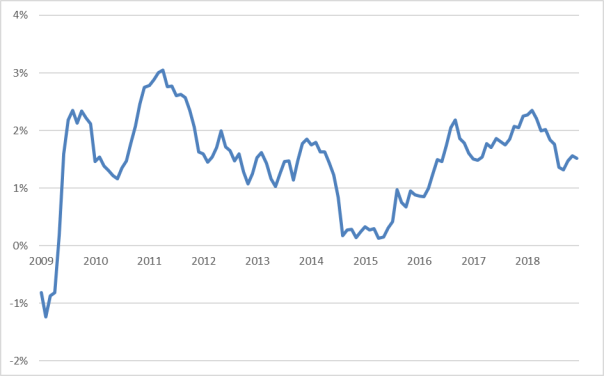

Economic theory predicts that low unemployment would push inflation higher, but this has not occurred recently. The Fed might be reducing rates because inflation has fallen below its 2% target, although the timing would be a little off—inflation first fell below 2% in October 2018 (or July 2018 if food and energy prices are excluded), and it has ticked back up again slightly since March (see Figure 4). However, the Fed might have wanted to ensure that inflation would remain persistently below 2% before cutting rates.

|

2009-2019 |

|

|

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis. Notes: 12 month change in Personal Consumption Expenditures Index. |

A key principle of monetary policy is that it should be forward looking because of lags between policy changes and their effect on the economy. When deciding to cut rates, the Fed should not consider only current economic performance, but also projections of future performance. As noted above, the Fed typically cuts rates before a recession has begun, and there are some recession warning signals, such as the yield curve inversion, which, if accurate, would justify lower rates. The Fed does not project a recession this year or next, however, so that would not seem to motivate its rate decision.

Despite its view that a sustained expansion and strong labor markets are the most likely outcomes, the Fed cited global developments and muted inflationary pressures as justification for cutting rates. There are always risks to the outlook, however, especially from abroad. Unlike the 1987 and 1998 episodes, there has been no major disruption in financial markets. (There were large declines in the stock market last December and May, but both subsequently completely reversed.) Some have described this cut as "insurance" in case conditions worsen, but cutting rates also poses a risk of overheating that could threaten the expansion.

Given the lack of official evidence that the economy has weakened, some question whether President Trump's repeated calls for the Fed to reduce rates has been effective. If so, this would raise questions about whether the Fed's independence has been compromised, which could have implications for the Fed's credibility going forward. When asked whether the President's requests have influenced Fed policy, Fed Chairman Jerome Powell recently testified "Not at all."