Overview

The Nuclear Security Enterprise

Responsibility for U.S. nuclear weapons resides with both the Department of Defense (DOD) and the Department of Energy (DOE). DOD develops, deploys, and operates the missiles and aircraft that can deliver nuclear warheads. It also generates the military requirements for the warheads carried on those platforms. The National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA), which is a semiautonomous agency within the Department of Energy, oversees the research, development, test, and acquisition programs that produce, maintain, and sustain the warheads. Moreover, DOE is responsible for storing and securing the warheads that are not deployed with DOD delivery systems and for dismantling warheads that have been retired and removed from the stockpile.

Congress authorizes funding for both DOD and NNSA nuclear weapons activities in the annual National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA). While Congress considers appropriations for DOD's nuclear weapons activities in the Defense Appropriations bill, it funds the NNSA budget through the Energy and Water Development Appropriations bill. This report focuses on the portion of the Energy and Water Development Appropriations Bill that funds NNSA's nuclear weapons activities.

Reorganization of the Nuclear Security Enterprise

During World War II, when the United States first developed nuclear weapons, the Army managed the nuclear weapons program. In 1946, Congress passed the Atomic Energy Act of 1946 to establish the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC). The AEC was an independent civilian agency tasked with managing the U.S. nuclear weapons program. In the Energy Research and Development Act of 1974, Congress dissolved the AEC and created the Nuclear Regulatory Commission and the Energy Research and Development Administration (ERDA), which among other functions managed the nuclear weapons program. That program was moved again by the Department of Energy Organization Act of 1977, which dissolved ERDA and created DOE.1

Congress, in passing the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2000 (P.L. 106-65, Title XXXII), established the National Nuclear Security Administration. NNSA is a semiautonomous agency operating within DOE. In addition to managing the nuclear weapons program, NNSA also manages the Defense Nuclear Nonproliferation and Naval Reactors programs.

These reorganizations stem, in part, from long-standing concerns about the management of the nuclear weapons complex. Many reports and legislative provisions have been written over the past several decades to address this issue. Most recently, in the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2013 (P.L. 112-239), Congress established the Congressional Advisory Panel on the Governance of the Nuclear Security Enterprise and directed the panel to make recommendations on "the most appropriate governance structure, mission, and management of the nuclear security enterprise." In its report to Congress, the panel stated

The panel finds that the existing governance structures and many of the practices of the enterprise are inefficient and ineffective, thereby putting the entire enterprise at risk over the long term. These problems have not occurred overnight; they are the result of decades of neglect. This is in spite of the efforts of many capable and dedicated people who must nonetheless function within the confines of a dysfunctional system.…

One unmistakable conclusion is that NNSA governance reform, at least as it has been implemented, has failed to provide the effective, mission-focused enterprise that Congress intended.2

The panel's recommendations included strengthening presidential guidance and oversight of the nuclear enterprise; establishing new congressional mechanisms for leadership and oversight of the enterprise; replacing NNSA with a new Office of Nuclear Security within DOE, renamed to the Department of Energy and Nuclear Security, with the Secretary responsible for the mission; and building a culture of performance, accountability, and credibility. NNSA, in its review of the report, supported many of the suggested changes in management and contracting within NNSA, but did not support the proposed changes in the name and structure of the organization or its leadership.

Congress has also expressed concerns about cost growth and transparency in NNSA's programs. These concerns focus on both major construction projects and weapons refurbishment programs. Congress addressed these concerns in the Consolidated and Further Continuing Appropriations Act for 2015 (P.L. 113-235). Section 304 required that NNSA's construction of high-hazard nuclear facilities have independent oversight by the Office of Independent Enterprise Assessments "to ensure the project is in compliance with nuclear safety requirements." Section 305 required an independent cost estimate for approving performance baseline and starting construction for projects with total cost over $100 million. Section 308 required the Secretary of Energy to provide an analysis of alternatives for each major warhead refurbishment program reaching the development engineering stage. The Senate reiterated its concerns in S.Rept. 114-54, its report on H.R. 2028, the Energy and Water Development and Related Agencies Appropriations Act, 2016. In this report, the committee expressed its concern "with the continued poor cost estimating by the Department, particularly within the NNSA," and directed the Secretary of Energy to "provide a report … that outlines the Department's plan for improving cost estimating for major projects and programs."

The Nuclear Weapons Complex

At the end of the Cold War in 1991, the U.S. nuclear weapons complex consisted of 14 sites—3 laboratories, the nuclear weapons test site in Nevada, and a number of manufacturing plants for weapons materials and components. As the number of nuclear weapons in the U.S. arsenal declined and demand for new warheads and materials abated in the 1990s, the United States closed several facilities in the complex.

The complex now consists of eight sites in seven states. These sites include three laboratories (Los Alamos National Laboratory, NM; Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, CA; and Sandia National Laboratories, NM and CA); four production sites (Kansas City Plant, MO; Pantex Plant, TX; Savannah River Site, SC; and Y-12 National Security Complex, TN); and the Nevada National Security Site (formerly Nevada Test Site). NNSA manages and sets policy for the complex; contractors operate the eight sites.3

Despite the post-Cold War reductions in the complex, some in Congress have pressed for further changes, seeking additional reductions in personnel, greater efficiencies in production, a smaller footprint at each site, and increased security. Many Members have also supported calls for increased investments within the complex, both to replace aging facilities and improve operations and security.

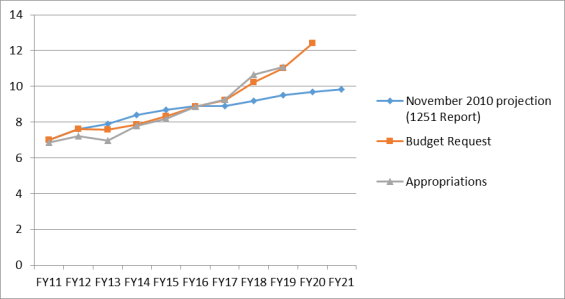

The Obama Administration requested increased funding for the nuclear weapons complex in each of its annual budgets. In an editorial published in late January 2010, Vice President Biden noted that U.S. nuclear laboratories and facilities had been "underfunded and undervalued" for more than a decade.4 He stated that the President's budget request for FY2011 would include "$7 billion for maintaining our nuclear-weapons stockpile and complex, and for related efforts," an amount that was $600 million more than Congress appropriated for FY2010. He also stated that the Administration would "boost funding for these important activities by more than $5 billion" over the next five years. While the passage of the Budget Control Act in late 2011 slowed the increases in NNSA budgets, as is evident in the figure below, the actual appropriations for NNSA's weapons activities have begun to exceed the expectations outlined in the 1251 Report in 2010.

The Obama Administration further outlined its funding plans for the nuclear weapons enterprise in a report submitted to Congress in May 2010, and updated in November 2010, in support of the ratification of the New START Treaty. Congress had requested this report, known as the "1251 report" in the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2010 (P.L. 111-84), Section 1251, and mandated that it outline a comprehensive plan to "(1) maintain delivery platforms [that is, bombers, missiles, and submarines that deliver nuclear weapons]; (2) sustain a safe, secure, and reliable U.S. nuclear weapons stockpile; and (3) modernize the nuclear weapons complex."5 In the November 2010 update of that document, the Administration projected weapons stockpile and infrastructure costs for FY2011-FY2020 at between $85.4 billion and $86.2 billion. As is shown in Figure 1, above, funds appropriated for these programs fell below the projected levels early in the decade. However, the FY2017, FY2018, and FY2019 budget requests and projections for subsequent years now exceed the amount predicted in the 2010 report.

The Trump Administration, in its budget for FY2018, requested an additional $1 billion for NNSA weapons activities over the level appropriated in FY2017. (NNSA's budget request showed an increase of $1.4 billion, but this compared FY2018 with FY2016 funding levels.) While the Administration had indicated in its "skinny budget" that this increase would support both deferred maintenance requirements among the NNSA weapons facilities and the warhead life extension programs in the directed stockpile area of the budget, funding for deferred maintenance in infrastructure and operations accounts remained essentially unchanged from the FY2017 appropriated levels. Most of the increases in the funding request for FY2018 divided between the life extension programs and research and development activities. Congress enacted a budget of $10.642 billion for weapons activities for NNSA in FY2018, in the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2018 (P.L. 115-141).

The Trump Administration's budget for FY2019 continued to fund increases in NNSA's weapons activities, requesting $11.02 billion, an increase of nearly $400 million over the funding enacted in FY2018. Congress enacted a budget of $11.1 billion for weapons activities in the Energy and Water, Legislative Branch, and Military Construction and Veterans Affairs Appropriations Act, 2019 (P.L. 115-244). The Administration's FY2020 budget requests $12.4 billion for NNSA's weapons activities accounts, an increase of $1.3 billion (12%) over the funding enacted in 2019. The House Energy and Water Appropriations Subcommittee recommended $11.7 billion—$660.8 million above the funding enacted for FY2019, but $647.8 million below the budget request for FY2020—in its version of the FY2020 Energy and Water Development and Related Agencies Appropriations Act (H.R. 2960, H.Rept. 116-83).

Managing the Nuclear Weapons Stockpile

The United States conducted 1,030 nuclear weapons test explosions between 1945 and 1992. These were the primary means by which the United States both determined whether its nuclear weapons designs would work and confirmed that the weapons remained reliable and effective as they aged. In 1992, Congress enacted a moratorium on U.S. nuclear weapons testing when it attached the Hatfield-Exon-Mitchell amendment to the Energy and Water Development Appropriations Act, 1993.6 President George H. W. Bush signed the bill into law (P.L. 102-377) on October 2, 1992.

In the absence of nuclear weapons testing, the United States has adopted a science-based program to maintain and sustain confidence in the reliability of the U.S. nuclear stockpile. Congress established the Stockpile Stewardship Program in the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 1994 (P.L. 103-160). This program, as amended by the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2010 (P.L. 111-84, §3111), is to ensure "that the nuclear weapons stockpile is safe, secure, and reliable without the use of underground nuclear weapons testing."

NNSA implements the Stockpile Stewardship Program through the activities funded by Weapons Activities account in the NNSA budget. This account includes three major program areas, each with a budget in excess of $2 billion, and several smaller programs. These are detailed below. The aggregate funding for these programs appears in Table 1.

|

Program |

FY2017 Request |

FY2017 Enacted |

FY2018 Request |

FY2018 Enacted |

FY2019 Request |

FY2019 Enacted |

FY2020 Request |

|

DSW |

3,330.5 |

3,308.3 |

3977.0 |

4,009.4 |

4,666.2 |

4,658.2 |

5.426 |

|

RDT&E Programs |

1,854.7 |

1,842.2 |

2028.3 |

2,034.4 |

1,995.4 |

2014.2 |

2.278 |

|

I&O |

2,721.9 |

2,808.4 |

2803.1 |

3,117.8 |

3,002.7 |

3087.9 |

3.208 |

|

Othera |

1,336.0 |

1,359.5 |

1430.8 |

1,480.5 |

1352.8 |

1,339.7 |

|

|

Total |

9,243.1 |

9,318,1 |

10,239.2 |

10,642.1 |

11,017.1 |

11,100.0 |

12.409 |

Sources: NNSA Congressional Budget Requests, House and Senate Appropriations Committee reports.

Notes: Details may not add to totals due to rounding. DSW: Directed Stockpile Work; RDT&E: Research, Development, Test and Evaluation; I&O: Infrastructure and Operations.

a. "Other" includes Secure Transportation Asset, Defense Nuclear Security, Information Technology and Cybersecurity, and Legacy Contractor Pensions.

Directed Stockpile Work (DSW)

According to NNSA's budget materials,7 Directed Stockpile Work includes those programs that directly support the nuclear weapons currently in the U.S. nuclear stockpile. These activities include maintenance and surveillance of existing warheads; refurbishment and life extension of existing warheads; assessments of the reliability of existing warheads; and the dismantlement and disposition of retired warheads. It also includes programs that support research, development, and certification of technology needed to meet stockpile requirements and strategic materials.

The NNSA budget requested $3,977 million for Directed Stockpile Work in FY2018. The House Energy and Water Appropriations Subcommittee, in its version of the bill (H.R. 3266), recommended the requested amount of $3,977 million for Directed Stockpile Work, while the Senate Energy and Water Appropriations Subcommittee (S. 1609) recommended $3,912.6 million, a reduction of $64.4 million from the budget request. The Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2018 (P.L. 115-141) included $4,009.4 million for Directed Stockpile Work.

NNSA requested $4,666.2 million for Directed Stockpile work in FY2019, an increase of 16.3% over the amount enacted in FY2018. The request increased funding in each of the program areas of DSW, although the Life Extension Programs and Strategic Materials programs received a proportionally larger share. Congress appropriated $4,658.3 million in the Energy and Water, Legislative Branch, and Military Construction and Veterans Affairs Appropriations Act, 2019 (P.L. 115-244). NNSA has requested $5,426.4 million for Directed Stockpile Work in FY2020, an increase of 16% ($768.1) million over the enacted funding level in FY2019. This increase is applied across the programs in DSW.

Life Extension Programs

Life Extension Programs (LEPs) are designed to extend the life of existing warheads through design, certification, manufacture, and replacement of components. An LEP for the W76 warhead for the Trident II (D-5) submarine-launched ballistic missile (SLBM), which includes a small number of low-yield W76-2 warheads, is concluding in FY2019. An LEP for the B61 mod 12 is ongoing. (A "mod," such as B61 mod 12 or B61-12, is a modification or version of a bomb or warhead type.) NNSA is also pursuing an alteration for the W88 warhead currently deployed on Trident II (D-5) missiles and a life extension program for the W80 cruise missile warhead. The new W80-4 will be deployed on the new Long Range Standoff missile (LRSO) currently under development by the Air Force. Finally, it is in the early stages of a life extension for the warhead deployed on U.S. land-based intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs). While NNSA initially expected to design a new warhead, known as the IW1 (interoperable warhead-1), it has now designated this program as the W87-1.

NNSA requested $1,920 million for LEPs in FY2019. As NNSA noted in its budget documents, this increase over the enacted level of $1,744 million in FY2018 was "primarily due to planned ramp-up of production activities for the B61-12 LEP and the W80-4 LEP." The FY2019 budget request also introduced the W76-2 LEP, noting that "the 2018 Nuclear Posture Review states that the United States will modify a small quantity of existing SLBM warheads to provide a low-yield option in the near-term." NNSA's initial budget request for FY2019 did not request any funding specifically allocated to this modification, but did note that "as the Nuclear Weapons Council translates policy into military requirements, the Administration will work with Congress for appropriate authorizations and appropriations to develop options that support the modification." The White House later included $65 million for the W76-2 in a budget amendment package submitted to Congress on April 13, 2018. This document stated that the amendment would "authorize the production of low-yield ballistic missiles to replace higher-yield weapons currently deployed, maintaining the overall number of deployed U.S. ballistic missile warheads." It noted that a delay in the program past FY2019 "would require a restart of the W76 production line, increase costs, and delay delivery to the Department of Defense."8 Congress enacted the requested funding levels for each of these LEP programs in FY2019.

NNSA has requested $2,117.4 million for life extension programs and major alterations in its FY2020 budget. This is an increase of $197.4 million, or 10.3% over the enacted level in FY2019.

- NNSA requested no additional funding for the W76-1 LEP in FY2020, a reduction from the $44 million enacted in FY2019 due to the "completion of remaining W76 warhead modifications and associated deliveries to the Navy."

- NNSA requested $10 million for the W76-2 LEP—the low-yield version of the warhead—in FY2020, a reduction from the $65 million enacted in FY2019. According to NNSA, "all warhead modifications [for the W76-2] will be complete by the end of FY 2019" and the funding for FY2020 will support program documentation and close out activities.

- NNSA requested $792.6 million for the B61-12 LEP in FY2020, a slight reduction from the $794 million enacted in FY2019. The B61-12 will combine four existing types of B61 warheads, and could eventually allow a reduction in the number of gravity bombs in the U.S. nuclear arsenal. The LEP would refurbish both nuclear and non‐nuclear components of the weapon to address aging, to extend the bomb's service life, and to improve the safety, effectiveness, and security of the bomb. The FPU is scheduled for FY2020.

- NNSA requested $304.2 million for the W88 Alteration in FY2020, to provide an arming-fuzing-firing system and to refresh the warhead's conventional high explosives. This warhead is carried on a portion of the D-5 (Trident) submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs). The FY2020 funding request is similar to the $304.3 million enacted for FY2019. NNSA expects to provide the First Production Unit of this warhead in 2020.

- NNSA requested 898.6 million for the W80-4 in FY2020, an increase of 37% over the $654.8 million enacted in FY2019. This is the warhead for the new long-range cruise missile. The LEP would seek to use common components from other LEPs and to improve warhead safety and security. NNSA has begun to "ramp up engineering activities for development and design on the W80-4," and the significant increases in the budget request for FY2020 reflect an increase in the scope of work on the program. It also includes additional resources identified in the Weapon Design and Cost Report that was completed in 2018. The FPU is scheduled for FY2025.

NNSA has requested $112 million for the W87-1 warhead modification program. According to NNSA, the W87-1 will replace the aging W78 warhead on U.S. ICBMs.9 The W78, which is the oldest warhead in the U.S. stockpile, dating from 1979, was originally supposed to be replaced by a new warhead, known as the IW1, which would have been an interoperable warhead that could be delivered by ICBMs (in place of the W78 warhead) and SLBMs (in place of the W88 warheads). The FY2016 budget request had suspended work on the IW1, and the FY2017 and FY2018 budgets did not request any funding for it. The FY2019 budget had requested $53 million to resume research and development activities on the IW1. Congress enacted this amount, but the conference report (H.Rept. 115-929) requested a study on the rationale for and alternatives to the plan to use an interoperable warhead as a part of the W78 life extension program. During 2019, NNSA dropped the IW1 designator and instead, pursued a life extension program for just the W78 ICBM warhead. It then designated this program as the W87-1, to reflect the fact that it has a similar primary design to the existing W87 ICBM warhead for the IW1. According to NNSA, the W87-1 will "provide enhanced safety and security compared to the legacy W78." The House Energy and Water Appropriations Subcommittee provided only $53 million for the W87-1 warhead modification, noting in its report (H.Rept. 116-83) that NNSA had not yet fulfilled the reporting requirements mandated by the FY2019 Act. The committee also noted its concern "with the initial projected cost and feasibility of the program" and, therefore, directed NNSA to seek a study from "the JASON Defense Advisory Panel or an FFRDC with expertise in assessing cost and technologies for national security programs to conduct an assessment" of the W87-1 LEP program.

Stockpile Systems

According to NNSA, Stockpile Systems programs provide for routine maintenance, replacement of limited-life components, surveillance, and assessment of fielded systems for all weapons types in the active stockpile. NNSA requested $619.5 million for Stockpile Systems in FY2019. The Senate approved the requested amount, but the House reduced it; Congress enacted $599.5 million in the Energy and Water, Legislative Branch, and Military Construction and Veterans Affairs Appropriations Act, 2019 (P.L. 115-244). NNSA has requested $635.8 million for Stockpile Systems in FY2020. Within this total, the largest increase is in support for the B83 gravity bomb. NNSA has requested $51.5 million for this weapon, an increase of 47% over the enacted funding of $35 million in FY2019. The Obama Administration had planned to retire the B83 bomb in the early 2020s, as the B61-12 entered the force, but the Trump Administration reversed that decision in the 2018 Nuclear Posture Review. Consequently, the added funding in Stockpile Systems will support the need to continue B83 sustainment activities. The NNSA budget also notes that the added funding will allow NNSA to conduct a study of the proposed new Sea-Launched Cruise Missile (SLCM), to continue technology developments for future weapon systems, and to maintain and modernize the NNSA's capabilities for hydrodynamic and subcritical experiments nuclear experiments.

Weapons Dismantlement and Disposition (WDD)

The number of warheads in the U.S. stockpile has fallen sharply since the end of the Cold War, and continues to decline. According to a fact sheet released by the State Department in 2017, the stockpile peaked at 31,255 warheads in 1967, stood at 19,008 warheads in 1991, and declined to 4,571 warheads by 2015.10 It had declined further, to 4,014 warheads by 2016 and 3,822 by 2017. Warheads removed from the stockpile are awaiting dismantlement. The WDD program includes the interim storage of warheads to be dismantled; actual dismantlement; and disposition (i.e., storing or eliminating warhead components and materials). NNSA requested $68.9 million for WDD for FY2017, an increase over the appropriated level of $52 million in FY2016. According to NNSA, this increase was designed to support President Obama's commitment, pledged at the 2015 Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty Review Conference, to accelerate dismantlement of retired U.S. nuclear warheads by 20%. The Senate Energy and Water Development Appropriations Subcommittee approved this request and noted in its report (S.Rept. 114-236) that it supported the accelerated dismantlement plan "as a way of preparing its workforce for necessary stockpile production work beginning later this decade." The House subcommittee, however, objected to the accelerated dismantlement plan and reduced total funding for directed stockpile work. The final version of the Consolidated Appropriations Act for FY2017 (P.L. 115-31) allocated only $56 million to weapons dismantlement and disposition.

NNSA requested $56 million for weapons dismantlement and disposition in FY2018 and FY2019; Congress approved this amount in both years. NNSA's budget documents note that funding for this program was capped at $56 million at the direction of the FY2017 and FY2018 National Defense Authorization Acts. NNSA also noted that dismantlement activities serve as "a significant supplier of material for future nuclear weapons production and Naval Reactors." Unlike in previous years, however, the FY2019 budget documents do not reiterate the goal, supported by previous budgets, of dismantling weapons retired prior to FY2009 by FY2022.

NNSA has requested $47 million for weapons dismantlement and disposition in FY2020. NNSA's budget request notes that the decline in funding requested for this program area "results from a reduction in legacy component disposition … consistent with material and component needs for the stockpile and external customers." Hence, as was the case in the FY2019 budget request, while the WDD program is still seen as a supplier of materials to the U.S. weapons stockpile, it is no longer seen as a component of U.S. nonproliferation policy.

Stockpile Services

According to NNSA's budget documents, programs under Stockpile Services "provide the logistical, mechanical and support foundation for all DSW operations that are applicable to multiple weapon system in the enduring stockpile." These activities include Production Support; Research and Development (R&D) Support; R&D Certification and Safety; Management, Technology, and Production; and Plutonium Infrastructure Sustainment. According to NNSA, "all enduring systems, LEPs, and dismantlements rely on Stockpile Services to provide the base development, production and logistics capability needed to meet program requirements." Stockpile Services also funds research, development, and production activities that support two or more weapons types, and work that is not identified or allocated to a specific weapon type.

NNSA requested $1,068.4 million for Stockpile Services in FY2019; Congress approved $1,048,7 million in the Energy and Water, Legislative Branch, and Military Construction and Veterans Affairs Appropriations Act, 2019 (P.L. 115-244). NNSA has requested $1,124.5 million for FY2020. According to NNSA, the increase in the FY2020 budget request supports, among other things, the "growth of base capabilities, both workforce and equipment, required to support the increased LEP workload" as the LEP programs read full-scale production rates. The House Energy and Water Appropriations Subcommittee recommended $1,053 million for Stockpile Services; it did not offer an explanation for this reduction in its report (H.Rept. 116-83).

Strategic Materials

According to NNSA's budget request, this program, which was new in FY2016, "consolidates management of nuclear material processing capabilities within the nuclear security enterprise." The program includes Uranium, Plutonium and Tritium Sustainment, Domestic Uranium Enrichment, and Strategic Materials Sustainment.

NNSA requested $1,002.4 million for Strategic Materials in FY2019. According to NNSA's budget documents, the substantial increase over FY2018 was needed "to meet future pit production and tritium requirements." Specifically, the budget request indicated that increases in the account for plutonium sustainment "support fabrication of four to five development" pits for the W87 warhead, investments to replace aging pit production equipment, and the installation of equipment that would increase pit production capacity. Moreover, as the 2018 Nuclear Posture Review emphasized the need to move forward on the design of a new pit production facility, the increased funding for plutonium sustainment also supported costs associated with design efforts that would support the "selection of a single preferred alternative for plutonium pit production beyond 30 war reserve pits per year." In addition, according to the budget documents, the increase in funding for domestic uranium enrichment "supports the start of an effort to down blend available stocks of highly enriched uranium for use in tritium production, which delays the need date for a domestic uranium enrichment capability."

Congress approved $1,034.1 million for Strategic Materials in the Energy and Water, Legislative Branch, and Military Construction and Veterans Affairs Appropriations Act, 2019 (P.L. 115-244). Within this total, Congress added $75 million to begin a Plutonium Pit production project. It noted in the conference report (H.Rept. 115-929) that some of this funding was to support ongoing programs at Los Alamos and it directed NNSA "to budget for capital improvements and equipment installations to meet plutonium pit production targets." It also mandated that NNSA provide Congress with a report "on the current scope, costs, and schedule required to meet its plutonium mission targets."

NNSA has requested $1,501 million for Strategic Materials in its FY2020 budget. Within this total, it has requested $712 million for plutonium sustainment, which represents a 97% increase over the $361.3 million enacted for plutonium sustainment in FY2019. The FY2020 budget documents note that this program has been restructured to support NNSA's May 2018 decision to pursue a new approach for plutonium pit production to meet the requirement of producing a minimum of 80 pits per year by 2030, as outlined in the 2018 Nuclear Posture Review. Instead of focusing solely on building capacity at Los Alamos National Laboratory, NNSA decided to "repurpose the Mixed Oxide (MOX) Fuel Fabrication Facility at the Savannah River Site to produce at least 50 pits per year" and to continue work that would allow Los Alamos to produce "no fewer than 30 pits per year."11 Consequently, NNSA has requested $420 million to support design activities at Savannah River and begin the modifications needed to produce 50 pits per year at the repurposed facility by 2030.

The House Energy and Water Development Appropriations Committee (H.Rept. 116-83) recommended funding of $1,260 million for Strategic Materials in FY2020 and reduced the requested funding for plutonium sustainment to $471.3 million. In its report, it noted that NNSA had not yet "provided the current cost, scope, and schedule to meet plutonium mission needs" as Congress had directed in the FY2019 Act. The committee also mandated that NNSA "include a separate line item for pit production activities at the Savannah River Site in the fiscal year 2021 budget request."

Research, Development, Test and Evaluation (RDT&E) Programs

According to NNSA's budget request, RDT&E includes five programs that focus on efforts "to develop and maintain critical capabilities, tools, and processes needed to support science based stockpile stewardship, refurbishment, and continued certification of the stockpile over the long-term in the absence of underground nuclear testing." It funds not only the science and engineering programs, but also large experimental facilities, such as the National Ignition Facility at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory.

Congress appropriated $2,014.2 million for RDT&E programs in FY2019 in the Energy and Water, Legislative Branch, and Military Construction and Veterans Affairs Appropriations Act, 2019 (P.L. 115-244). NNSA has requested $2,277.9 million in its budget for FY2020.

Specific programs under RDT&E include the following.

Science Program

According to NNSA's budget documents, the Science Program provides "the knowledge and expertise, and the confidence needed to maintain the nuclear stockpile without nuclear testing." It performs experiments that allow NNSA to understand the physics of nuclear explosions and to validate nuclear weapons performance simulations. Its goals include improving the ability to assess warhead performance without nuclear testing, improving readiness to conduct nuclear tests should the need arise, and maintaining the scientific infrastructure of the nuclear weapons laboratories. According to NNSA, this program provides the basis for annual assessments of weapon performance, the understanding of the impacts of surveillance findings to ensure that the nuclear stockpile continues to meet military requirements, and the core technical expertise required to be responsive to global nuclear security policy questions.

NNSA requested $564.9 million for the Science Program in FY2019, an increase of 19% over the enacted amount of $474.5 million in FY2018. The budget request included a significant increase in funding for the Dynamic Materials Properties program (from $120 million to $131 million) and for Enhanced capabilities for subcritical experiments (from $40.1 million to $117,6 million). Congress approved $480.5 million for this program area in the Energy and Water, Legislative Branch, and Military Construction and Veterans Affairs Appropriations Act, 2019 (P.L. 115-244). It did not approve the increase for the DMP program, holding its FY2019 funding to the $120 million approved for FY2018. It also reduced the request for Enhanced capabilities for subcritical experiments to $50 million.

NNSA has requested $586.6 million for the Science Program in FY2020. It has again requested increases in funding for the Dynamic Materials Properties Program (from $120 million to $133 million) and Enhanced Capabilities for Subcritical Experiments (from $50 million to $145.1 million.) According to NNSA's budget documents, the funding increase for the Enhanced Capabilities for Subcritical Experiments program is needed, generally, to support the stockpile stewardship program, and, specifically, to "improve NNSA's plutonium experimental capabilities." The House Energy and Water Development Appropriations Committee (H.Rept. 116-83) recommended full funding for this program area.

Engineering Program

The Engineering Program is responsible for "creating and maturing advanced toolsets and capabilities necessary to maintain a safe, secure, and effective nuclear weapons stockpile and enhance nuclear weapon safety, security, and use-control." According to NNSA, this program "matur[es] advanced technologies to improve weapon surety; provid[es] the tools for qualifying weapon components and certifying weapons without underground testing; and support[s] annual stockpile assessments."

NNSA requested $211.4 million for the Engineering Program in FY2019. According to the budget documents, this request includes funding to conduct "a robust Stockpile Responsiveness Program in coordination with DOD." NNSA had added this program to its budget request in FY2018, in response to congressional direction, to establish a joint working group with the DOD that will pursue "efforts that sustain, enhance, and exercise capabilities required to conceptualize, study, design, develop, engineer, certify, produce, and deploy nuclear weapons to ensure the U.S. nuclear deterrent remains safe, secure, reliable, credible, and responsive." Congress approved $190.1 million for the Engineering Program in the Energy and Water, Legislative Branch, and Military Construction and Veterans Affairs Appropriations Act, 2019 (P.L. 115-244).

NNSA has requested $234 million for the Engineering Program in FY2020. The House Energy and Water Development Appropriations Committee (H.Rept. 116-83) recommended $179.4 million for this program area, and specifically reduced funding for Stockpile Responsiveness from the requested level of $39.8 million to $5 million.

Inertial Confinement Fusion Ignition and High Yield Program

This program is developing tools to create extremely high temperatures and pressures in the laboratory—approaching those of a nuclear explosion—to support weapons-related research and to attract scientific talent to the Stockpile Stewardship Program. The centerpiece of this campaign is the National Ignition Facility (NIF), the world's largest laser, located at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. NIF is intended to produce "ignition," the point at which a nuclear fusion reaction generates more energy than is used by the lasers to create the reaction. While achieving ignition has been delayed, NIF has nonetheless proven to be of value to stockpile stewardship at energy levels that do not reach ignition. NIF was controversial in Congress for many years, but controversy waned as the program progressed. NIF was dedicated in May 2009.12 The program also supports the Z Facility at the Sandia National Laboratories (SNL), and the Omega Laser Facility (Omega) at the University of Rochester's Laboratory for Laser Energetics (LLE).

NNSA requested $419 million for this program area in FY2019, a steep reduction from the $544.9 million appropriated in FY2018. Within this total, NNSA requested $258.8 million for NIF, $63.1 million for the Z facility (with an additional $55 million for the Z facility coming from the Science program), and $40.4 million for the Omega Laser Facility. Congress rejected the Administration's request to "to discontinue major experimental activities" in this program area and appropriated $544.9 million for this program area in the Energy and Water, Legislative Branch, and Military Construction and Veterans Affairs Appropriations Act, 2019 (P.L. 115-244). Within this total, Congress allocated $344 million for NIF, $63.1 million for the Z Facility, $80 million for Omega, and $7 million for the Naval Research Laboratory.

NNSA has requested $480.6 million for this program area in its FY2020 budget, a reduction of nearly 12% from the $544.9 enacted in FY2019. It reduced by nearly half the Ignition and Other Stockpile Programs area, from $101.1 million in FY2019 to $55.6 million in FY2020. NNSA's budget documents note that this reduction, and others in this program area, reflect a shift in funding to "higher priority NNSA efforts." Within this total, NNSA requested $278.3 million for NIF, $66.9 million for the Z facility (with an additional $24.9 million for the Z facility coming from the Science program), and $50.6 million for the Omega Laser Facility. The House Energy and Water Development Appropriations Committee (H.Rept. 116-83) recommended $565 million for this program area, noting that "the recommendation includes additional funding to offset the cost of target fabrication." It also recommended $344 million for the NIF, $66.9 million for the Z Facility, and not less than $80 million for the OMEGA Laser Facility.

Advanced Simulation and Computing (ASC) Program

The ASC program develops computation-based models of nuclear weapons that integrate data from other campaigns, past test data, and laboratory experiments, to create what NNSA calls "the computational surrogate for nuclear testing to determine weapon behavior." NNSA notes that "modeling the extraordinary complexity of nuclear weapons systems is essential to maintaining confidence in the performance of our aging stockpile without underground testing." This program also supports nonproliferation, emergency response, and nuclear forensics.

NNSA requested $656.4 million for FY2019, a reduction from the $721 million appropriated in FY2018. Congress approved $670.1 million in the Energy and Water, Legislative Branch, and Military Construction and Veterans Affairs Appropriations Act, 2019 (P.L. 115-244). NNSA has requested $839.8 million for this program area in its FY2020 budget. The House Energy and Water Development Appropriations Committee (H.Rept. 116-83) recommended full funding for this program area.

Advanced Manufacturing Development

Through FY2015, this program was called the Readiness Campaign. It had several subprograms, but the entire FY2015 request was for the Nonnuclear Readiness subprogram, which "develops capabilities to manufacture components used for Directed Stockpile Work." Congress did not fund this program in FY2015, and, instead, recommended that NNSA establish an Advanced Manufacturing Development program "to develop, demonstrate, and utilize advanced technologies that are needed to enhance the NNSA's secure manufacturing capabilities and ensure timely support for the production of nuclear weapons and other critical national security components."13 According to NNSA, this program allows it to significantly reduce cost and schedule risk associated with the development and production of stockpile components by exploring the development of an array of advanced technologies and then ensure those technologies can be used to produce components for the stockpile.

NNSA requested $96.8 million for this program area in FY2019. Congress approved $81.6 million in the Energy and Water, Legislative Branch, and Military Construction and Veterans Affairs Appropriations Act, 2019 (P.L. 115-244). NNSA requested $136.9 million for this program area in its FY2020 budget. It notes that this increased funding will "support expansion of additive manufacturing for specific stockpile components, development of new manufacturing processes to replace hazardous and obsolete processes, and advanced technologies for new weapon systems." The House Energy and Water Development Appropriations Committee (H.Rept. 116-83) recommended $104.9 million.

Infrastructure and Operations (I&O)

Prior to FY2016, the Infrastructure and Operations Program area was known as Readiness in Technical Base and Facilities. According to NNSA's budget documents, funding for this program "maintains, operates, and modernizes the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) infrastructure." It not only provides "a comprehensive approach to arresting the declining state of NNSA infrastructure while maximizing return on investment," but also "constructs state-of-the-art facilities, infrastructure, and scientific tools" needed to maintain a safe, secure, and effective nuclear arsenal. There is widespread agreement that NNSA's infrastructure is in need of significant upgrades, with some facilities dating from early in the nuclear age. NNSA requested a nearly 20% increase in funding for I&O in FY2017, from the level of $2,279.1 million enacted in for FY2016 to $2,722 million requested for FY2017. Congress allocated $2,808.4 million in FY2017, $86.4 million more than the budget request. This level declined slightly in the FY2018 budget, with a request for $2,803.1 million. The House committee added $5.2 million, returning the budget to the FY2017 level of $2,808.4 million. The Senate committee reduced the request, approving $2,722.1 million for FY2018. However, Congress provided $3,117.8 million in the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2018 (P.L. 115-141.)

NNSA has $3,002.7 million for this program area in FY2019. The is funding was designed to "continue the long-term effort to reverse the declining state of NNSA infrastructure, improve working conditions of NNSA's aging facilities and equipment, and address safety and programmatic risks." Congress approved $3087.9 million in the Energy and Water, Legislative Branch, and Military Construction and Veterans Affairs Appropriations Act, 2019 (P.L. 115-244). The House report (H.Rept. 115-697) had specifically raised concerns that NNSA was "undercutting the investments needed to address the entirety of its aging infrastructure problems and to build a nuclear weapons workforce that possesses the skills and knowledge needed to design, develop, test, and manufacture warheads" to "pay for the projected costs of its major nuclear modernization programs."

NNSA has requested $3208.4 million for this program area in its FY2020 budget. NNSA notes that this increase will, among other things, "continue the stabilization of deferred maintenance" and "execute recapitalization projects to improve the condition and extend the design life of structures, capabilities, and systems."

Specific programs under I&O include the following:

Operations of Facilities

The Operations of Facilities program includes the funding needed to "operate NNSA facilities in a safe and secure manner." It contains, essentially, the operating budgets for each of the eight NNSA sites, funding such areas as "water and electrical utilities; safety systems; lease agreements; and activities associated with Federal, state, and local environmental, and worker safety and health regulations." NNSA requested $868 million for this program area in FY2018. According to NNSA's budget documents, this budget supported necessary work on transuranic waste in preparation for shipment to the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant (WIPP); the transition to operations of new waste facilities at Los Alamos National Lab; and rising reimbursement requirements for Savannah River Nuclear Solutions pension plans at SRS. Congress approved $848.4 million and included funding to prepare and ship transuranic waste, but noted that, prior to the use of these funds "the NNSA's Office of Cost Estimating and Program Evaluation shall conduct a comparative analysis of the costs and benefits of shipping TRU waste from LLNL to Idaho for processing that includes consideration of the benefits of compacting waste for disposal in the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant."

NNSA requested $891 million for this program area in FY2019, an increase over the $848.4 million approved in FY2018. According to the budget documents, the funding increase would "provide for transitioning new facilities to operations, lease payments, and programmatic tempo increases." There is no mention, in the budget, of preparing transuranic waste for shipment to WIPP. Congress approved $870 million for this program area in the Energy and Water, Legislative Branch, and Military Construction and Veterans Affairs Appropriations Act, 2019 (P.L. 115-244).

NNSA has requested $905 million for this program area in its FY2020 budget. The House Energy and Water Development Appropriations Committee (H.Rept. 116-83) recommended $870 million, the same as the amount enacted in FY2019.

Safety and Environmental Operations

According to NNSA's budget documents, the Safety and Environmental Operations program "support[s] safe, efficient operation of the nuclear security enterprise through the provision of safety data; environmental monitoring; and nuclear material packaging." NNSA has requested $119 million for FY2020; The House Energy and Water Development Appropriations Committee (H.Rept. 116-83) recommended $110 million.

Maintenance and Repair of Facilities

The Maintenance and Repair of Facilities program funds the "recurring day-to-day work required to sustain and preserve NNSA facilities and equipment in a condition suitable for their designated purpose." This is the program area that addresses the backlog in deferred maintenance at NNSA facilities. NNSA requested $294 million for this program area in FY2017; Congress provided $324 million as a part of the effort to address the backlog. NNSA requested $360 million for this program area in FY2018. In the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2018 (P.L. 115-141), Congress provided $515.1 million. It noted that it had included "funds above the budget request to address the significant backlog of deferred maintenance at the NNSA's sites and to make progress on the direction provided in the Fiscal Year 2012 Energy and Water Appropriations Act to establish standardized policies for the direct funding of facility and infrastructure maintenance costs at each of the NNSA sites."

NNSA requested $365 million for this program area in FY2019. The budget documents note that, at the direction of Congress and the 2018 NDAA, NNSA had created an Infrastructure Modernization Initiative (IMI) to reduce deferred maintenance and repair needs across the enterprise "by not less than 30 percent by 2025." Congress approved $515 million in the Energy and Water, Legislative Branch, and Military Construction and Veterans Affairs Appropriations Act, 2019 (P.L. 115-244), noting in the conference report (H.Rept. 115-697) that it had added funding to "address the significant backlog of deferred maintenance at the NNSA's sites."

NNSA has requested $456 million for this program area in its FY2020 budget. The documents note that overall funding for maintenance "has grown significantly but appropriately over the last several budget cycles" and that the decrease in the FY2020 request "allows the sites to absorb the significant increases in FY2018 and FY2019 funding by increasing staffing levels to address the long-standing deficiency of a robust maintenance program." The House Energy and Water Development Appropriations Committee (H.Rept. 116-83) recommended the requested amount.

Recapitalization

According to NNSA, the Recapitalization program is key to arresting the declining state of NNSA infrastructure. The program, which funds two subprograms—Infrastructure and Safety and Capabilities-Based Investments—is intended to address obsolete support and safety systems, revitalize aging facilities, and improve the reliability, efficiency, and capability of core infrastructure. This is a key area where NNSA sought to increase funding in FY2017. NNSA requested $667.3 million for FY2017, an increase of almost 90% over the appropriated level of $352.5 million in FY2016. In the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2017, Congress provided $743.1 million, as a part of the effort to address the deteriorating infrastructure and backlog of deferred maintenance at NNSA facilities.

NNSA requested $427.3 million in FY2018, showing a reduction from the FY2017 appropriation. Budget documents note that this reduction reflected the completion of the work at the Bannister Federal Complex in Kansas City. Congress, however, provided $612.6 million for this program area, noting it had included "funds above the budget request to address the NNSA's high-risk excess facilities and deferred maintenance." NNSA requested $540.7 million in FY2019; Congress approved $559 million.

NNSA has requested $583 million for Recapitalization in its FY2020 budget. According to the budget documents, this funding is needed to "address numerous obsolete support and safety systems; revitalize facilities that are beyond the end of their design life; and improve the reliability, efficiency, and capability of core infrastructure to meet mission requirements." The House Energy and Water Development Appropriations Committee (H.Rept. 116-83) recommended $556.7 million.

Construction

According to NNSA's budget documents, the Construction program focuses on two primary objectives: identifying construction projects that are needed to support the objectives of the weapons program and developing and executing of these projects within approved cost and schedule baselines. NNSA is currently planning or managing 20 projects through this program area. This includes two controversial and expensive projects—the Uranium Processing Facility (UPF) at the Y-12 National Security Complex (TN) and the Chemistry and Metallurgy Research Replacement (CMRR) Project, which deals with plutonium, at Los Alamos National Laboratory (NM). Both have been significantly revised over the past several years due to cost growth and schedule slippage.

NNSA requested $1,031.8 million for Construction in FY2018. Within this total, it requested $663 million for UPF and $180.9 million for CMRR. The budget documents note that FY2018 funding would allow it to initiate construction and procurement for UPF's Main Process Building, Mechanical Electrical Building, and Salvage and Accountability Building subprojects. It also noted that the funding would support continued construction in CMRR to sustain plutonium science activities. The Senate committee recommended the requested amount for UPF, but the House committee recommended only $620 million for UPF. It noted, in its report, that this had been the expected FY2018 appropriation in FY2017. The committee deferred the funding that NNSA had requested "to address project cost growth until a full independent cost estimate has been provided to the Committees on Appropriations of both Houses of Congress."

In the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2018 (P.L. 115-141), Congress provided $663 million for UPF and $177.2 million for CMRR.

NNSA requested $1,091 million for construction in FY2019. Within this total, it requested $703 million for UPF and $235.1 million for CMRR. The budget documents note that NNSA remains "committed to complete UPF by 2025 for no more than $6,500 million," assuming consistent and stable funding for the program. The documents also note that NNSA plans to move forward with three subprojects under CMRR that have already received funding and to begin design work on two additional subprojects. Congress approved $1033.8 million for Construction in the Energy and Water, Legislative Branch, and Military Construction and Veterans Affairs Appropriations Act, 2019 (P.L. 115-244), and included the $703 million for UPF and $219.8 million for CMRR.

NNSA has requested $1,145.4 million for Construction in its FY2020 budget request. The budget documents note that much of the increase over the FY2019-enacted level of $1033.8 million "primarily reflects funding for construction of the UPF at Y-12, the High Explosive Science & Engineering Facility at Pantex, and the U1a Complex Enhancements Project" at National Nuclear Security Site (NNSS) in Nevada. Specifically, NNSA has requested $745 million for UPF, but only $168 million for CMRR. The reduction in funding for CMRR reflects a more limited scope for the project. The House Energy and Water Development Appropriations Committee (H.Rept. 116-83) recommended $997.6 million for Construction in FY2020. It recommended no funding for the High Explosive Science & Engineering Facility at Pantex and reduced the request for UPF to $703 million.

Other Programs

Weapons Activities has several smaller programs, including the following.

Secure Transportation Asset

This program provides for safe and secure transport of nuclear weapons, components, and materials. It includes special vehicles for this purpose, communications and other supporting infrastructure, and threat response. NNSA has sought significant increases in funding in this program in recent years, although Congress did not approve the requested amounts. For example, NNSA sought $282.7 million in FY2017, an increase of 19% over the FY2016-enacted level to allow it to increase the number of federal agents working on the program; maintain and replace critical vehicles; and resume candidate training classes that had been cancelled for several years due to budget shortfalls. Congress provided $249 million for FY2017. In FY2018, NNSA requested $325 million, noting that it needed the significant increase to develop specialized vehicles, maintain a force of well-trained agents, and sustain a robust communication system. Congress approved $291.1 million. In FY2019, NNSA reversed course and requested $278.6 million for this program area, a reduction of 14% from the FY2018 request. Nevertheless, in its budget documents, NNSA indicated that this funding level would allow it to continue to support improvements in its specialized vehicles and staffing needs. Congress approved this request in the Energy and Water, Legislative Branch, and Military Construction and Veterans Affairs Appropriations Act, 2019 (P.L. 115-244).

NNSA has requested $317.2 million for this program area in the FY2020 budget request, an increase of $38.5 million over the amount enacted in FY2019. The budget request indicates that this funding will support "critical workforce capabilities and asset modernization initiatives and restore Federal Agent strength levels required to meet the STA mission capacity."

Defense Nuclear Security

According to NNSA's budget documents, this program "provides protection for NNSA personnel, facilities, and nuclear weapons and materials from a full spectrum of threats, ranging from local security incidents to terrorism." It provides operations, maintenance, and construction funds for protective forces, physical security systems, and personnel security. NNSA requested, and Congress approved, $690 million for this program area in FY2019. It has requested $778.2 million for this program area in FY2020. According to NNSA's budget request, this "includes funding to fill positions in key security program areas at the sites, including protective forces, physical security systems, information security, technical security, personnel security, nuclear material control and accountability, and security program operations and planning."

Information Technology and Cybersecurity

According to NNSA's budget documents, this program provides funding "to develop information technology and cybersecurity solutions, including continuous monitoring, and security technologies to help meet increased proliferation-resistance and security." It also funds programs to consolidate NNSA's IT services. NNSA requested and Congress approved $221.2 million for this program area in FY2019. NNSA has requested $309 million for FY2020. The budget documents indicate that the funding for FY2020 will allow for the continued "integration and coordination of cybersecurity and information technology support activities and functions throughout the NNSA nuclear security enterprise."

Legacy Contractor Pensions

For many decades, the University of California (UC) operated Los Alamos and Lawrence Livermore National Laboratories. Laboratory employees, as UC employees, could participate in the UC pension plan. When the contracts for the labs' operations were taken over by private corporations, the contracts between DOE and the new laboratory operators included provisions that provided pensions to employees who had worked under the UC contract that mirrored the UC pension benefits. These pensions were larger than those provided to employees hired after the contracts were granted to private employers. To make up the difference, NNSA has paid into the pension plan for those current employees who formerly worked under the UC system. NNSA requested $91 million for legacy contractor pensions in FY2020, a reduction of $71.1 million for the amount enacted in FY2019. According to NNSA, this does not represent a change in the program; it is based on the needs of the program and the funded status of the plan.