The Constitution's Supremacy Clause provides that "the Laws of the United States . . . shall be the supreme Law of the Land; and the Judges in every State shall be bound thereby, any Thing in the Constitution or Laws of any State to the Contrary notwithstanding."1 This language is the foundation for the doctrine of federal preemption, according to which federal law supersedes conflicting state laws.2

Federal preemption of state law is a ubiquitous feature of the modern regulatory state and "almost certainly the most frequently used doctrine of constitutional law in practice."3 Indeed, preemptive federal statutes shape the regulatory environment for most major industries, including drugs and medical devices, banking, air transportation, securities, automobile safety, and tobacco.4 As a result, "[d]ebates over the federal government's preemption power rage in the courts, in Congress, before agencies, and in the world of scholarship."5 These debates over federal preemption implicate many of the themes that recur throughout the federalism literature. Proponents of broad federal preemption often cite the benefits of uniform national regulations6 and the concentration of expertise in federal agencies.7 In contrast, opponents of broad preemption often appeal to the importance of policy experimentation,8 the greater democratic accountability that they believe accompanies state and local regulation,9 and the "gap-filling" role of state common law in deterring harmful conduct and compensating injured plaintiffs.10

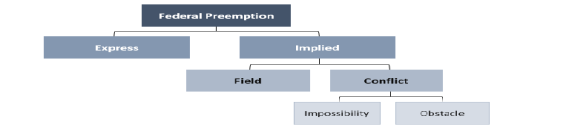

These broad normative disputes occur throughout the Supreme Court's preemption case law. However, the Court has also identified different ways in which federal law can preempt state law, each of which raises a unique set of narrower interpretive issues. As Figure 1 illustrates, the Court has identified two general ways in which federal law can preempt state law. First, federal law can expressly preempt state law when a federal statute or regulation contains explicit preemptive language. Second, federal law can impliedly preempt state law when its structure and purpose implicitly reflect Congress's preemptive intent.11

The Court has also identified two subcategories of implied preemption: "field preemption" and "conflict preemption." Field preemption occurs when a pervasive scheme of federal regulation implicitly precludes supplementary state regulation, or when states attempt to regulate a field where there is clearly a dominant federal interest.12 In contrast, conflict preemption occurs when compliance with both federal and state regulations is a physical impossibility ("impossibility preemption"),13 or when state law poses an "obstacle" to the accomplishment of the "full purposes and objectives" of Congress ("obstacle preemption").14

|

|

Source: CRS. |

While the Supreme Court has repeatedly distinguished these preemption categories, it has also explained that the presence of an express preemption clause in a federal statute does not preclude implied preemption analysis. In Geier v. American Honda Motor Co., the Court held that although a preemption clause in a federal automobile safety statute did not expressly displace state common law claims involving automobile safety, the federal statute and associated regulations nevertheless impliedly preempted those claims based on conflict preemption principles.15 Congress must therefore consider the possibility that the laws it enacts may be construed as impliedly preempting certain categories of state law even if those categories do not fall within the explicit terms of a preemption clause.

This report provides a general overview of federal preemption to inform Congress as it crafts laws implicating overlapping federal and state interests. The report begins by reviewing two general principles that have shaped the Court's preemption jurisprudence: the primacy of congressional intent and the "presumption against preemption." The report then discusses how courts have interpreted certain language that is commonly used in express preemption clauses. Next, the report reviews judicial interpretations of statutory provisions designed to insulate certain categories of state law from federal preemption ("savings clauses"). Finally, the report discusses the Court's implied preemption case law by examining illustrative examples of its field preemption, impossibility preemption, and obstacle preemption decisions.

General Preemption Principles

The Primacy of Congressional Intent

The Supreme Court has repeatedly explained that in determining whether (and to what extent) federal law preempts state law, the purpose of Congress is the "ultimate touchstone" of its statutory analysis.16 The Court has further instructed that Congress's intent is discerned "primarily" from a statute's text.17 However, the Court has also noted the importance of statutory structure and purpose in determining how Congress intended specific federal regulatory schemes to interact with related state laws.18 Like many of its statutory interpretation cases, then, the Court's preemption decisions often involve disputes over the appropriateness of consulting extra-textual evidence to determine Congress's intent.19

The Presumption Against Preemption

In evaluating congressional purpose, the Court has at times employed a canon of construction commonly referred to as the "presumption against preemption," which instructs that federal law should not be read to preempt state law "unless that was the clear and manifest purpose of Congress."20 The Court regularly appealed to this principle in the 1980s and 1990s,21 but has invoked it inconsistently in recent cases.22 Moreover, in a 2016 decision, the Court departed from prior case law23 when it held that the presumption no longer applies in express preemption cases.24

The Court's repudiation of the presumption in express preemption cases can be traced to the growing popularity of textualist approaches to statutory interpretation, as many textualists have expressed skepticism about such "substantive" canons of construction.25 Unlike "semantic" or "linguistic" canons, which express rules of thumb concerning ordinary uses of language,26 substantive canons favor or disfavor particular outcomes—even when those outcomes do not follow from the most natural reading of a statute's text.27 Because of these effects, prominent textualists have expressed suspicion about substantive canons' legitimacy.28 According to textualist critics of the presumption against preemption, a statute's inclusion of a preemption clause provides sufficient evidence of Congress's intent to preempt state law.29 These critics contend that in light of this clear expression of congressional intent, preemption clauses should be given their "ordinary meaning" rather than any narrower constructions that the presumption might dictate.30 The Supreme Court ultimately adopted this position in its 2016 decision in Puerto Rico v. Franklin California Tax-Free Trust.31

The Court has also endorsed certain narrower exceptions to the presumption against preemption. Specifically, the Court has declined to apply the presumption in cases involving (1) subjects which the states have not traditionally regulated,32 and (2) areas in which the federal government has traditionally had a "significant" regulatory presence.33 In Buckman Company v. Plaintiffs' Legal Committee, for example, the Court declined to apply the presumption when it held that federal law preempted state law claims alleging that a medical device manufacturer had defrauded the Food and Drug Administration during the pre-market approval process for its device.34 The Court refused to apply the presumption in Buckman on the grounds that states have not traditionally policed fraud against federal agencies, reasoning that the relationship between federal agencies and the entities they regulate is "inherently federal in character."35 Likewise, in Arizona v. Inter Tribal Council of Arizona, Inc., the Court declined to apply the presumption in holding that the National Voter Registration Act preempted a state law requiring voter-registration officials to reject certain registration applications.36 In refusing to apply the presumption, the Court explained that state regulation of congressional elections "has always existed subject to the express qualification that it terminates according to federal law."37

Similarly, the Court has declined to apply the presumption in cases involving areas in which the federal government has traditionally had a "significant" regulatory presence.38 In United States v. Locke, the Court held that the federal Ports and Waterways Safety Act preempted state regulations regarding navigation watch procedures, crew English language skills, and maritime casualty reporting based in part on the fact that the state laws concerned maritime commerce—an area in which there was a "history of significant federal presence."39 In such an area, the Court explained, "there is no beginning assumption that concurrent regulation by the State is a valid exercise of its police powers."40

However, the status of the Locke exception to the presumption against preemption is unclear. In its 2009 decision in Wyeth v. Levine, the Court invoked the presumption when it held that federal law did not preempt certain state law claims concerning drug labeling.41 In allowing the claims to proceed, the Court acknowledged that the federal government had regulated drug labeling for more than a century, but explained that the presumption can apply even when the federal government has long regulated a subject.42 This reasoning stands in some tension with the Court's conclusion in Locke that the presumption does not apply when states regulate an area where there has been a "history of significant federal presence."43 Whether the presumption continues to apply in fields traditionally regulated by the federal government accordingly remains unclear.

Language Commonly Used in Express Preemption Clauses

Congress often relies on the language of existing preemption clauses in drafting new legislation.44 Moreover, when statutory language has a settled meaning, courts often look to that meaning to discern Congress's intent.45 This section of the report discusses how the Supreme Court has interpreted federal statutes that preempt (1) state laws "related to" certain subjects, (2) state laws concerning certain subjects "covered" by federal laws and regulations, (3) state requirements that are "in addition to, or different than" federal requirements, and (4) state "requirements," "laws," "regulations," and "standards." While preemption decisions depend heavily on the details of particular statutory schemes, the Court has assigned some of these phrases specific meanings even when they have appeared in different statutory contexts.

"Related to"

Preemption clauses frequently provide that a federal statute supersedes all state laws that are "related to" a specific matter of federal regulatory concern. The Supreme Court has characterized such provisions as "deliberatively expansive"46 and "conspicuous for [their] breadth."47 At the same time, however, the Court has cautioned against strictly literal interpretations of "related to" preemption clauses. Instead of reading such clauses "to the furthest stretch of [their] indeterminacy,"48 the Court has relied on legislative history and purpose to cabin their scope.49 The following subsections discuss the Court's interpretation of three statutes that contain "related to" preemption clauses: the Employee Retirement Income Security Act, the Airline Deregulation Act, and the Federal Aviation Administration Authorization Act.

Employee Retirement Income Security Act

The Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA) contains perhaps the most prominent example of a preemption clause that uses "related to" language.50 ERISA imposes comprehensive federal regulations on private employee benefit plans, including (1) detailed reporting and disclosure obligations,51 (2) schedules for the vesting, accrual, and funding of pension benefits,52 and (3) the imposition of certain duties of care and loyalty on plan administrators.53 The statute also contains a preemption clause providing that its requirements preempt all state laws that "relate to" regulated employee benefit plans.54 In interpreting this provision, the Supreme Court has identified two categories of state laws that are preempted by ERISA because they "relate to" regulated employee benefit plans: (1) state laws that have a "connection with" such plans, and (2) state laws that contain a "reference to" such plans.55

The Court has held that state laws have an impermissible "connection with" ERISA plans if they govern or interfere with "a central matter of plan administration."56 In contrast, state laws that indirectly affect ERISA plans are not preempted unless the relevant effects are particularly "acute."57 Applying these standards, the Court has held that ERISA preempts state laws governing areas of "core ERISA concern," like the designation of ERISA plan beneficiaries58 and the disclosure of data regarding health insurance claims.59 In contrast, the Court has held that ERISA does not preempt state laws imposing surcharges on certain types of insurers60 and mandating wage levels for specific categories of employees who work on public projects.61 The Court has explained that these state laws are permissible because they affect ERISA plans only indirectly, and that ERISA preempts such laws only if the relevant indirect effects are particularly "acute."62

The Court has also held that ERISA preempts state laws that contain an impermissible "reference to" ERISA plans. Under the Court's case law, a state law will contain an impermissible "reference to" ERISA plans where it "acts immediately and exclusively upon ERISA plans," or where the existence of an ERISA plan is "essential" to the state law's operation.63 In Mackey v. Lanier Collection Agency & Service, Inc., for example, the Court held that ERISA—which does not prohibit creditors from garnishing funds in regulated employee benefit plans—preempted a state statute that prohibited the garnishment of funds in plans "subject to . . . [ERISA]."64 Because the challenged state statute expressly referenced ERISA plans, the Court held that it fell within the scope of ERISA's preemption clause even if it was enacted "to help effectuate ERISA's underlying purposes."65 Similarly, in Ingersoll-Rand Company v. McClendon, the Court held that ERISA—which provides a federal cause of action for employees discharged because of an employer's desire to prevent a regulated pension from vesting—preempted an employee's state law claim alleging that he was terminated in order to prevent his regulated pension from vesting.66 The Court reasoned that ERISA preempted this state law claim because the action made "specific reference to" and was "premised on" the existence of an ERISA-regulated pension plan.67 Finally, in District of Columbia v. Greater Washington Board of Trade, the Court held that ERISA preempted a state statute that required employers providing health insurance to their employees to continue providing coverage at existing benefit levels while employees received workers' compensation benefits.68 The Court reached this conclusion on the grounds that ERISA regulated the relevant employees' existing health insurance coverage, meaning that the state law specifically referred to ERISA plans.69

Airline Deregulation Act

The Airline Deregulation Act (ADA) is another example of a statute that employs "related to" preemption language.70 Enacted in 1978, the ADA largely deregulated domestic air transportation, eliminating the federal Civil Aeronautics Board's authority to control airfares.71 In order to ensure that state governments did not interfere with this deregulatory effort, the ADA prohibited states from enacting laws "relating to a price, route, or service of an air carrier."72 The Supreme Court's interpretation of the ADA's preemption clause has largely followed its ERISA decisions in applying the "connection with" and "reference to" standards. In Morales v. Trans World Airlines, Inc., for example, the Court relied in part on its ERISA case law to conclude that the ADA preempted state consumer protection statutes prohibiting deceptive airline fare advertisements.73 Specifically, the Court reasoned that because the challenged state statutes expressly referenced airfares and had a "significant effect" on them, they "related to" airfares within the meaning of the ADA's preemption clause.74

Federal Aviation Administration Authorization Act

The Federal Aviation Administration Authorization Act of 1994 (FAAA) is a third example of a statute that utilizes "related to" preemption language.75 While the FAAA (as its title suggests) is principally concerned with aviation regulation, it also supplemented Congress's deregulation of the trucking industry. The statute pursued this objective with a preemption clause prohibiting states from enacting laws "related to a price, route, or service of any motor carrier . . . with respect to the transportation of property."76 In interpreting this language, the Supreme Court has relied on the "connection with" standard from its ERISA and ADA case law. However, the Court has also acknowledged that the clause's "with respect to" qualifying language significantly narrows the FAAA's preemptive scope.

In Rowe v. New Hampshire Motor Transport Association, the Supreme Court relied in part on its ERISA and ADA case law to hold that the FAAA preempted certain state laws regulating the delivery of tobacco, including a law that required retailers shipping tobacco to employ motor carriers that utilized certain kinds of recipient-verification services.77 The Court reached this conclusion for two principal reasons. First, the Court reasoned that the requirement had an impermissible "connection with" motor carrier services because it "focuse[d] on" such services.78 Second, the Court concluded that the state law fell within the terms of the FAAA's preemption clause because of its effects on the FAAA's deregulatory objectives. Specifically, the Court reasoned that the state law had a "connection with" these objectives because it dictated that motor carriers use certain types of recipient-verification services, thereby substituting the state's commands for "competitive market forces."79

However, the Court has also held that the FAAA's "with respect to" qualifying language significantly narrows the statute's preemptive scope. In Dan's City Used Cars, Inc. v. Pelkey, the Court relied on this language to hold that the FAAA did not preempt state law claims involving the storage and disposal of a towed car.80 Specifically, the Court held that the FAAA did not preempt state law claims alleging that a towing company (1) failed to provide the plaintiff with proper notice that his car had been towed, (2) made false statements about the condition and value of the car, and (3) auctioned the car despite being informed that the plaintiff wanted to reclaim it.81 In allowing these claims to proceed, the Court observed that the FAAA's preemption clause mirrored the ADA's preemption clause with "one conspicuous alteration"—the addition of the phrase "with respect to the transportation of property."82 According to the Court, this phrase "massively" limited the scope of FAAA preemption.83 And because the relevant state law claims involved the storage and disposal of towed vehicles rather than their transportation, the Court held that they did not qualify as state laws that "related to" motor carrier services "with respect to the transportation of property."84

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's case law concerning "related to" preemption clauses reflects a number of general principles. The Court has consistently held that state laws "relate to" matters of federal regulatory concern when they have a "connection with" or contain a "reference to" such matters.85 Generally, state laws have an impermissible "connection with" matters of federal concern when they prescribe rules specifically directed at the same subject as the relevant federal regulatory scheme,86 or when their indirect effects on the federal scheme are particularly "acute."87 As a corollary to the latter principle, the Court has made clear that state laws having only "tenuous, remote, or peripheral" effects on an issue of federal concern are not sufficiently "related to" the issue to warrant preemption.88 In contrast, a state law contains an impermissible "reference to" a matter of federal regulatory interest (and therefore "relates to" such a matter) when it "acts immediately and exclusively upon" the matter, or where the existence of a federal regulatory scheme is "essential" to the state law's operation.89 Finally, the inclusion of qualifying language can narrow the scope of "related to" preemption clauses. As the Court made clear in Dan's City, the scope of "related to" preemption clauses can be significantly limited by the addition of "with respect to" qualifying language.90

"Covering"

The Supreme Court has interpreted a preemption clause that allowed states to enact regulations related to a subject until the federal government adopted regulations "covering" that subject as having a narrower effect than "related to" preemption clauses. The Court reached this conclusion in CSX Transportation, Inc. v. Easterwood, where it interpreted a preemption clause in the Federal Railroad Safety Act allowing states to enact laws related to railroad safety until the federal government adopted regulations "covering the subject matter" of such laws.91 In Easterwood, the Court explained that "covering" is a "more restrictive term" than "related to," and that federal law will accordingly "cover" the subject matter of a state law only if it "substantially subsume[s]" that subject.92

Applying this standard, the Court held that federal laws and regulations did not preempt state law claims alleging that a train operator failed to maintain adequate warning devices at a grade crossing where a collision had occurred.93 The Court allowed these claims to proceed on the grounds that the relevant federal regulations—which required states receiving federal railroad funds to establish a highway safety program and "consider" the dangers posed by grade crossings—did not "substantially subsume" the subject of warning device adequacy.94 Specifically, the Court reasoned that the federal regulations did not "substantially subsume" this subject because they established the "general terms of the bargain" between the federal government and states receiving federal funds, but did not reflect an intent to displace supplementary state regulations.95

However, the Easterwood Court held that federal law preempted other state law claims alleging that the relevant train traveled at an unsafe speed despite complying with federal maximum-speed regulations. In holding that these claims were preempted, the Court reasoned that federal maximum-speed regulations "substantially subsumed" (and therefore "covered") the subject of train speeds because they comprehensively regulated that issue, reflecting an intent to preclude additional state regulations.96 Accordingly, while the Court has made clear that "covering" preemption clauses of the sort at issue in Easterwood have a narrower effect than "related to" clauses, specific determinations that federal law "covers" a subject will depend heavily on the details of particular regulatory schemes.

"In addition to, or different than"

A number of federal statutes preempt state requirements that are "in addition to, or different than" federal requirements.97 The Supreme Court has explained that these statutes preempt state law even in cases where a regulated entity can comply with both federal and state requirements. The Court adopted this position in National Meat Association v. Harris, where it interpreted a preemption clause in the Federal Meat Inspection Act (FMIA) prohibiting states from imposing requirements on meatpackers and slaughterhouses that are "in addition to, or different than" federal requirements.98 In Harris, the Court held that certain California slaughterhouse regulations were "in addition to, or different than" federal regulations because they imposed a distinct set of requirements that went beyond those imposed by federal law.99 Because the California requirements differed from federal requirements, the Court explained, they fell within the plain meaning of the FMIA's preemption clause even if slaughterhouses were able to comply with both sets of restrictions.100

Preemption clauses that employ "in addition to, or different than" language often raise a second interpretive issue involving the status of state requirements that are identical to federal requirements ("parallel requirements"). The Supreme Court has interpreted two statutes employing this language to not preempt parallel state law requirements.101 In instructing lower courts on how to assess whether state requirements in fact parallel federal requirements, the Court has explained that state law need not explicitly incorporate federal standards in order to avoid qualifying as "in addition to, or different than" federal requirements.102 Rather, the Court has indicated that state requirements must be "genuinely equivalent" to federal requirements in order to avoid preemption under such clauses.103 One lower court has interpreted this instruction to mean that state restrictions do not genuinely parallel federal restrictions if a defendant could violate state law without having violated federal law.104

The Court has also explained that state requirements do not qualify as "in addition to, or different than" federal requirements simply because state law provides injured plaintiffs with different remedies than federal law.105 Accordingly, absent contextual evidence to the contrary, preemption clauses that employ "in addition to, or different than" language will allow states to give plaintiffs a damages remedy for violations of state requirements even where federal law does not offer such a remedy for violations of parallel federal requirements.106

"Requirements," "Laws," "Regulations," and "Standards"

Federal statutes frequently preempt state "requirements," "laws," "regulations," and/or "standards" concerning subjects of federal regulatory concern.107 These preemption clauses have required the Supreme Court to determine whether such terms encompass state common law actions (as opposed to state statutes and regulations) involving the relevant subjects.

The Supreme Court has explained that absent evidence to the contrary, a preemption clause's reference to state "requirements" includes state common law duties.108 In contrast, the Court has interpreted one preemption clause's reference to state "law[s] or regulation[s]" as encompassing only "positive enactments" and not common law actions.109 The Court reached this conclusion in Sprietsma v. Mercury Marine, where it considered the meaning of a preemption clause in the Federal Boat Safety Act of 1971 (FBSA) prohibiting states from enforcing "a law or regulation" concerning boat safety that is not identical to federal laws and regulations.110 The FBSA also includes a "savings clause" providing that compliance with the Act does not "relieve a person from liability at common law or under State law."111 In Sprietsma, the Court held that the phrase "a law or regulation" in the FBSA did not encompass state common law claims for three reasons.112 First, the Court reasoned that the inclusion of the article "a" before "law or regulation" implied a "discreteness" that is reflected in statutes and regulations, but not in common law.113 Second, the Court concluded that the pairing of the terms "law" and "regulation" indicated that Congress intended to preempt only positive enactments. Specifically, the Court reasoned that if the term "law" were given an expansive interpretation that included common law claims, it would also encompass "regulations" and thereby render the inclusion of that latter term superfluous.114 Finally, the Court reasoned that the FBSA's savings clause provided additional support for the conclusion that the phrase "law or regulation" did not encompass common law actions.115

Lastly, while the Court had the opportunity to determine whether a preemption clause's use of the term "standard" encompassed state common law actions in Geier v. American Honda Motor Co., Inc., it ultimately declined to take up that question and resolved the case on other grounds discussed in greater detail below.116

Savings Clauses

Many federal statutes contain provisions that purport to restrict their preemptive effect. These "savings clauses" make clear that federal law does not preempt certain categories of state law, reflecting Congress's recognition of the need for states to "fill a regulatory void" or "enhance protection for affected communities" through supplementary regulation.117 The law regarding savings clauses "is not especially well developed," and cases involving such clauses "turn very much on the precise wording of the statutes at issue."118 With these caveats in mind, this section discusses three general categories of savings clauses: (1) "anti-preemption provisions," (2) "compliance savings clauses," and (3) "remedies savings clauses."

Anti-Preemption Provisions

Some savings clauses contain language indicating that "nothing in" the relevant federal statute "may be construed to preempt or supersede" certain categories of state law,119 or that the relevant federal statute "does not annul, alter, or affect" state laws "except to the extent that those laws are inconsistent" with the federal statute.120 Certain statutes containing this "inconsistency" language further provide that state laws are not "inconsistent" with the relevant federal statute if they provide greater protection to consumers than federal law.121 Some courts and commentators have labeled these clauses "anti-preemption provisions."122

While the case law on anti-preemption provisions is not well-developed, some courts have addressed such provisions in the context of defendants' attempts to remove state law actions to federal court. Specifically, certain courts have relied on anti-preemption provisions to reject removal arguments premised on the theory that federal law "completely" preempts state laws concerning the relevant subject. In Bernhard v. Whitney National Bank, for example, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit relied on an anti-preemption provision in the Electronic Funds Transfer Act to reject a defendant-bank's attempt to remove state law claims involving unauthorized funds transfers to federal court.123 A number of federal district courts have also adopted similar interpretations of other anti-preemption provisions.124

Compliance Savings Clauses

Some savings clauses provide that compliance with federal law does not relieve a person from liability under state law.125 The principal interpretive issue with such clauses is whether they limit a statute's preemptive effect (a question of federal law) or are instead intended to discourage the conclusion that compliance with federal regulations necessarily renders a product nondefective as a matter of state tort law.126

While the Supreme Court has not adopted a generally applicable rule concerning the meaning of compliance savings clauses, it has concluded that such clauses can support a narrow interpretation of a statute's preemptive effect. In Geier v. American Honda Motor Co., Inc., the Court relied in part on a compliance savings clause in the National Traffic and Motor Vehicle Safety Act (NTMVSA) to hold that the statute did not expressly preempt state common law claims against an automobile manufacturer.127 The NTMVSA contains (1) a preemption clause prohibiting states from enforcing safety standards for motor vehicles that are not identical to federal standards,128 and (2) a "savings clause" providing that compliance with federal safety standards does not "exempt any person from any liability under common law."129 In Geier, the Court explained that although it was "possible" to read the NTMVSA's preemption clause standing alone as encompassing the state law claims, that reading of the statute would leave the Act's savings clause without effect.130 The Court accordingly held that the NTMVSA did not expressly preempt the state law claims based in part on the Act's savings clause.131 Similarly, in Sprietsma v. Mercury Marine, the Court reasoned that a nearly identical savings clause in the FBSA "buttresse[d]" the conclusion that state common law claims did not qualify as "law[s] or regulation[s]" within the meaning of the statute's preemption clause.132 The Court has accordingly relied on compliance savings clauses to inform its interpretation of express preemption clauses, but has not held that such clauses automatically insulate state laws from preemption.

Remedies Savings Clauses

Some savings clauses provide that "nothing in" a federal statute "shall in any way abridge or alter the remedies now existing at common law or by statute."133 While the case law on these "remedies savings clauses" is limited, the Supreme Court has interpreted one such clause as evincing Congress's intent to disavow field preemption, but not as preserving state laws that conflict with federal objectives.134

"State" Versus "State or Political Subdivision Thereof"

Some savings clauses limit a federal statute's preemptive effect on certain laws enacted by "State[s] or political subdivisions thereof,"135 while others by their terms protect only "State" laws.136 The Supreme Court has twice held that savings clauses that by their terms applied only to "State" laws also insulated local laws from preemption. In Wisconsin Public Intervenor v. Mortier, the Court held that the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act did not preempt local ordinances regulating pesticides based in part on a savings clause providing that "State[s]" may regulate federally registered pesticides in certain circumstances.137 In concluding that the term "State" included political subdivisions of states, the Court relied on the principle that local governments are "convenient agencies" by which state governments can exercise their powers.138 Similarly, in City of Columbus v. Ours Garage & Wrecker Service, the Court held that the Interstate Commerce Act (ICA) did not preempt municipal safety regulations governing tow-truck operators based in part on a savings clause providing that the ICA "shall not restrict the safety regulatory authority of a State with respect to motor vehicles."139 Relying in part on its reasoning in Mortier, the Court explained that absent a clear statement to the contrary, Congress's reference to the regulatory authority of a "State" should be read to preserve "the traditional prerogative of the States to delegate their authority to their constituent parts."140

Implied Preemption

As discussed, federal law can impliedly preempt state law even when it does not do so expressly.141 Like its express preemption decisions, the Supreme Court's implied preemption cases focus on Congress's intent.142 The Supreme Court has recognized two general forms of implied preemption. First, "field preemption" occurs when a pervasive scheme of federal regulation implicitly precludes supplementary state regulation, or when states attempt to regulate a field where there is clearly a dominant federal interest.143 Second, "conflict preemption" occurs when state law interferes with federal goals.144

Field Preemption

The Supreme Court has held that federal law preempts state law where Congress has manifested an intention that the federal government occupy an entire field of regulation.145 Federal law may reflect such an intent through a scheme of federal regulation that is "so pervasive as to make reasonable the inference that Congress left no room for States to supplement it," or where federal law concerns "a field in which the federal interest is so dominant that the federal system will be assumed to preclude enforcement of state laws on the same subject."146 Applying these principles, the Court has held that federal law occupies a variety of regulatory fields, including alien registration,147 nuclear safety,148 aircraft noise,149 the "design, construction, alteration, repair, maintenance, operation, equipping, personnel qualification, and manning" of tanker vessels,150 wholesales of natural gas in interstate commerce,151 and locomotive equipment.152

Examples

Grain Warehousing

In its 1947 decision in Rice v. Santa Fe Elevator Corporation, the Supreme Court held that federal law preempted a number of fields related to grain warehousing, precluding even complementary state regulations of those fields.153 In that case, the Court held that the federal Warehouse Act and associated regulations preempted a variety of state law claims brought against a grain warehouse, including allegations that the warehouse had engaged in unfair pricing, maintained unsafe elevators, and impermissibly mixed different qualities of grain.154 The Court discerned Congress's intent to occupy the relevant fields from an amendment to the Warehouse Act that made the Secretary of Agriculture's authorities "exclusive" vis-à-vis federally licensed warehouses.155 Because the text and legislative history of this amendment reflected Congress's intent to eliminate overlapping federal and state warehouse regulations, the Court held that federal law occupied a number of fields involving grain warehousing. As a result, the Court concluded that the Warehouse Act preempted certain state law claims that intruded into those federally regulated fields, even if federal law established standards that were "more modest" and "less pervasive" than those imposed by state law.156

Immigration: Alien Registration

The Court has also held that federal law preempts the field of alien registration.157 In its 1941 decision in Hines v. Davidowitz, the Court held that federal immigration law—which required aliens to register with the federal government—preempted a Pennsylvania law that required aliens to register with the state, pay a registration fee, and carry an identification card.158 In reaching this conclusion, the Court explained that because alien regulation is "intimately blended and intertwined" with the federal government's core responsibilities and Congress had enacted a "complete" regulatory scheme involving that field, federal law preempted the additional Pennsylvania requirements.159

The Court reaffirmed these general principles from Hines in its 2012 decision in Arizona v. United States.160 In Arizona, the Court held that the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA), which requires aliens to carry an alien registration document,161 preempted an Arizona statute that made violations of that federal requirement a crime under state law.162 In holding that federal law preempted this Arizona requirement, the Court explained that like the statutory framework at issue in Hines, the INA represented a "comprehensive" regulatory regime that "occupied the field of alien registration."163 Specifically, the Court inferred Congress's intent to occupy this field from the INA's "full set of standards governing alien registration," which included specific penalties for noncompliance.164 The Court accordingly held that federal law preempted even "complementary" state laws regulating alien registration like the challenged Arizona requirement.165

However, the Court has also made clear that other types of state laws concerning aliens do not necessarily fall within the preempted field of alien registration. In its 1976 decision in De Canas v. Bica, the Court held that federal law did not preempt a California law prohibiting the employment of aliens not entitled to lawful residence in the United States.166 The Court reached this conclusion on the grounds that nothing in the text or legislative history of the INA—which did not directly regulate the employment of such aliens at the time—suggested that Congress intended to preempt all state regulations concerning the activities of aliens.167 Instead, the Court reasoned that while the INA comprehensively regulated the immigration and naturalization processes, it did not address employment eligibility for aliens without legal immigration status.168 As a result, the Court held that the challenged California law fell outside the preempted field of alien registration.169 The Court has also upheld several state laws regulating the activities of aliens since De Canas. In Chamber of Commerce v. Whiting, for example, the Court held that federal law did not preempt an Arizona statute allowing the state to revoke an employer's business license for hiring aliens who did not possess work authorization.170 The Court has accordingly made clear that the preempted field of alien registration does not encompass all state laws concerning aliens.

Nuclear Energy: Safety Regulation

The Supreme Court has also held that federal law preempts the field of nuclear safety regulation. However, the Court has explained this field does not encompass all state laws that affect safety decisions made by nuclear power plants. Instead, the Court has concluded that state laws fall within the preempted field of nuclear safety regulation if they (1) are motivated by safety concerns and implicate a "core federal power," or (2) have a "direct and substantial" effect on safety decisions made by nuclear facilities.171

This division of authority is the result of a regulatory regime that has changed significantly over the course of the 20th century. Before 1954, the federal government maintained a monopoly over the use, control, and ownership of nuclear technology.172 However, in 1954, the Atomic Energy Act (AEA) allowed private entities to own, construct, and operate nuclear power plants subject to a "strict" licensing and regulatory regime administered by the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC).173 In 1959, Congress amended the AEA to give the states greater authority over nuclear energy regulation. Specifically, the 1959 Amendments allowed states to assume responsibility over certain nuclear materials as long as their regulations were "coordinated and compatible" with federal requirements.174 While the 1959 Amendments reserved certain key authorities to the federal government, they also affirmed the states' ability to regulate "activities for purposes other than protection against radiation hazards."175 Congress reorganized the administrative framework surrounding these regulations in 1974, when it replaced the AEC with the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC).176

The Supreme Court has held that while this regulatory scheme preempts the field of nuclear safety regulation, certain state regulations of nuclear power plants that have a non-safety rationale fall outside this preempted field. The Court identified this distinction in Pacific Gas and Electric Company v. State Energy Resources Conservation & Development Commission, where it held that federal law did not preempt a California statute regulating the construction of new nuclear power plants.177 Specifically, the California statute conditioned the construction of new nuclear power plants on a state agency's determination concerning the availability of adequate storage facilities and means of disposal for spent nuclear fuel.178 In challenging this state statute, two public utilities contended that federal law made the federal government the "sole regulator of all things nuclear."179 However, the Court rejected this argument, reasoning that while Congress intended that the federal government regulate nuclear safety, the relevant statutes reflected Congress's intent to allow states to regulate nuclear power plants for non-safety purposes.180 The Court then concluded that the California law survived preemption because it was motivated by concerns over electricity generation and the economic viability of new nuclear power plants—not a desire to intrude into the preempted field of nuclear safety regulation.181

In addition to holding that the AEA does not preempt all state statutes and regulations concerning nuclear power plants, the Court has upheld certain state tort claims related to injuries sustained by power plant employees. In Silkwood v. Kerr-McGee Corporation, the Court upheld a punitive damages award against a nuclear laboratory arising from an employee's injuries from plutonium contamination.182 In upholding the damages award, the Court rejected the laboratory's argument that the award impermissibly punished and deterred conduct related to the preempted field of nuclear safety.183 Instead, the Court concluded that federal law did not preempt such damages awards because it found "no indication" that Congress had ever seriously considered such an outcome.184 Moreover, the Court observed that Congress had failed to provide alternative federal remedies for persons injured in nuclear accidents.185 According to the Court, this legislative silence was significant because it was "difficult to believe" that Congress would have removed all judicial recourse from plaintiffs injured in nuclear accidents without an explicit statement to that effect.186 The Court also reasoned that Congress had assumed the continued availability of state tort remedies when it adopted a 1957 amendment to the AEA.187 Under the relevant amendment, the federal government partially indemnified power plants for certain liabilities for nuclear accidents—a scheme that reflected an assumption that plaintiffs injured in such accidents retained the ability to bring tort claims against the power plants.188 Based on this evidence, the Court rejected the argument that Congress's occupation of the field of nuclear safety regulation preempted all state tort claims arising from nuclear incidents.189

The Court applied this reasoning from Silkwood six years later in English v. General Electric Company, where it held that federal law did not preempt state tort claims alleging that a nuclear laboratory had retaliated against a whistleblower for reporting safety concerns.190 In allowing the claims to proceed, the Court rejected the argument that federal law preempts all state laws that affect plants' nuclear safety decisions. Rather, the Court explained that in order to fall within the preempted field of nuclear safety regulation, a state law must have a "direct and substantial" effect on such decisions.191 While the Court acknowledged that the relevant tort claims may have had "some effect" on safety decisions by making retaliation against whistleblowers more costly than safety improvements, it concluded that such an effect was not sufficiently "direct and substantial" to bring the claims within the preempted field.192 In making this assessment, the Court relied on Silkwood, where it held that the relevant punitive damages award fell outside the field of nuclear safety regulation despite its likely impact on safety decisions.193 Because the Court concluded that the type of damages award at issue in Silkwood affected safety decisions "more directly" and "far more substantially" than the whistleblower's retaliation claims, it held that the retaliation claims were not preempted.194

Conclusion

A determination that federal law preempts a field has powerful consequences, displacing even state laws and regulations that are consistent with or complementary to federal law.195 However, because of these effects, the Court has cautioned against overly hasty inferences that Congress has occupied a field.196 Specifically, the Court has rejected the argument that the comprehensiveness of a federal regulatory scheme is sufficient to conclude that federal law occupies a field, explaining that Congress and federal agencies often adopt "intricate and complex" laws and regulations without intending to assume exclusive regulatory authority over the relevant subjects.197 The Court has accordingly relied on legislative history and statutory structure—in addition to the comprehensiveness of federal regulations—in assessing field preemption arguments.198

The Court has also adopted a narrow view of the scope of certain preempted fields. For example, the Court has rejected the proposition that federal nuclear energy regulations preempt all state laws that affect the preempted field of nuclear safety regulation, explaining that state laws fall within that field only if they have a "direct and substantial" effect on it.199 As a corollary to this principle, the Court has held that in certain contexts, generally applicable state laws are more likely to fall outside a federally preempted field than state laws that "target" entities or issues within the field. In Oneok, Inc. v. Learjet, Inc., for example, the Court held that state antitrust claims against natural gas pipelines fell outside the preempted field of interstate natural gas wholesaling because the relevant state antitrust law was not "aimed" at natural gas companies and instead applied broadly to all businesses.200

Finally, the Court's case law underscores that Congress can narrow the scope of a preempted field with explicit statutory language. In Pacific Gas, for example, the Court held that the preempted field of nuclear safety regulation did not encompass state laws motivated by non-safety concerns based in part on a statutory provision disavowing such an intent.201 While the Court has subsequently narrowed the circumstances in which it will apply Pacific Gas's purpose-centric inquiry to state laws affecting nuclear energy,202 it has reaffirmed the general principle that Congress can circumscribe a preempted field's scope with such "non-preemption clauses."203

Conflict Preemption

Federal law also impliedly preempts conflicting state laws.204 The Supreme Court has identified two subcategories of conflict preemption. First, federal law impliedly preempts state law when it is impossible for regulated parties to comply with both sets of laws ("impossibility preemption").205 Second, federal law impliedly preempts state laws that pose an obstacle to the "full purposes and objectives" of Congress ("obstacle preemption").206 The two subsections below discuss these subcategories of conflict preemption.

Impossibility Preemption

The Supreme Court has held that federal law preempts state law when it is physically impossible to comply with both sets of laws.207 To illustrate this principle, the Court has explained that a hypothetical federal law forbidding the sale of avocados with more than 7% oil content would preempt a state law forbidding the sale of avocados with less than 8% oil content, because avocado sellers could not sell their products and comply with both laws.208 The Court has characterized impossibility preemption as a "demanding defense,"209 and its case law on the issue is not as well-developed as other areas of its preemption jurisprudence.210 However, the Court extended impossibility preemption doctrine in two recent decisions concerning prescription drug labeling.

Example: Generic Drug Labeling

In PLIVA v. Mensing and Mutual Pharmaceutical Co. v. Bartlett, the Court held that federal regulations of generic drug labels preempted certain state law claims brought against generic drug manufacturers because it was impossible for the manufacturers to comply with both federal and state law.211 In both cases, plaintiffs alleged that they suffered adverse effects from certain generic drugs and argued that the drugs' labels should have included additional warnings.212 In response, the drug manufacturers argued that the Hatch-Waxman Amendments (Hatch-Waxman) to the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act preempted the state law claims.213 Under Hatch-Waxman, drug manufacturers can secure Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval for generic drugs by demonstrating that they are equivalent to a brand-name drug already approved by the FDA.214 In doing so, the generic drug manufacturers need not comply with the FDA's standard preapproval process, which requires extensive clinical testing and the development of FDA-approved labeling.215 However, generic drug makers that use the streamlined Hatch-Waxman process must ensure that the labels for their drugs are the same as the labels for corresponding brand-name drugs, meaning that generic manufacturers cannot unilaterally change their labels.216

In both PLIVA and Bartlett, the Court held that the Hatch-Waxman Amendments preempted the relevant state law claims because it was impossible for the generic drug manufacturers to comply with both federal and state law.217 Specifically, the Court reasoned that it was impossible for the drug makers to comply with both sets of laws because federal law prohibited them from unilaterally altering their labels, while the state law claims depended on the existence of a duty to make such alterations.218 In other words, the Court reasoned that it was impossible for the manufacturers to comply with both their state law duty to change their labels and their federal duty to keep their labels the same.219 In reaching this conclusion in PLIVA, the Court rejected the argument that it was possible for manufacturers to comply with both federal and state law by petitioning the FDA to impose new labeling requirements on the corresponding brand-name drugs.220 The Court rejected this argument on the grounds that impossibility preemption occurs whenever a party cannot independently comply with both federal and state law without seeking "special permission and assistance" from the federal government.221 Similarly, in Bartlett, the Court rejected the argument that it was possible for generic drug makers to comply with both federal and state law by refraining from selling the relevant drugs. The Court rejected this "stop-selling" argument on the grounds that it would render impossibility preemption "all but meaningless."222 As a result, an evaluation of whether it is "impossible" to comply with both federal and state law must presuppose some affirmative conduct by the regulated party.

Despite its decisions in PLIVA and Bartlett, the Court has rejected impossibility preemption arguments made by brand-name drug manufacturers, who are entitled to unilaterally strengthen the warning labels for their drugs. In Wyeth v. Levine, the Court held that federal law did not preempt a state law failure-to-warn claim brought against the manufacturer of a brand-name drug, reasoning that it was possible for the manufacturer to strengthen its label for the drug without FDA approval.223 However, the Wyeth Court noted that an impossibility preemption defense may be available to brand-name drug manufacturers when there is "clear evidence" that the FDA would have rejected a proposed change to a brand-name drug's label.224

Obstacle Preemption

Federal law also impliedly preempts state laws that pose an "obstacle" to the "full purposes and objectives" of Congress.225 In its obstacle preemption cases, the Court has held that state law can interfere with federal goals by frustrating Congress's intent to adopt a uniform system of federal regulation, conflicting with Congress's goal of establishing a regulatory "ceiling" for certain products or activities, or by impeding the vindication of a federal right.226 However, the Court has also cautioned that obstacle preemption does not justify a "freewheeling judicial inquiry" into whether state laws are "in tension" with federal objectives, as such a standard would undermine the principle that "it is Congress rather than the courts that preempts state law."227 The subsections below discuss a number of cases in which the Court has held that state law poses an obstacle to the accomplishment of federal goals.

Example: Foreign Sanctions

The Supreme Court has concluded that state laws can pose an obstacle to the accomplishment of federal objectives by interfering with Congress's choice to concentrate decisionmaking in federal authorities. The Court's decision in Crosby v. National Foreign Trade Council illustrates this type of conflict between state law and federal policy goals.228 In Crosby, the Court held that a federal statute imposing sanctions on Burma preempted a Massachusetts statute that restricted state agencies' ability to purchase goods or services from companies doing business with Burma.229 The Court identified several ways in which the Massachusetts law interfered with the federal statute's objectives. First, the Court reasoned that the Massachusetts law interfered with Congress's decision to provide the President with the flexibility to add or waive sanctions in response to ongoing developments by "imposing a different, state system of economic pressure against the Burmese political regime."230 Second, the Court explained that because the Massachusetts statute penalized certain individuals and conduct that Congress explicitly excluded from federal sanctions, it interfered with the federal statute's goal of limiting the economic pressure imposed by the sanctions to "a specific range."231 In identifying this conflict, the Court rejected the state's argument that its law "share[d] the same goals" as the federal act, reasoning that the additional sanctions imposed by the state law would still undermine Congress's intended "calibration of force."232 Finally, the Court concluded that the Massachusetts law undermined the President's capacity for effective diplomacy by compromising his ability "to speak for the Nation with one voice."233

Example: Automobile Safety Regulations

The Court has concluded that some federal laws and regulations evince an intent to establish both a regulatory "floor" and "ceiling" for certain products and activities. The Court has interpreted certain federal automobile safety regulations, for example, as not only imposing minimum safety standards on carmakers, but as insulating manufacturers from certain forms of stricter state regulation as well. In Geier v. American Honda Motor Co., the Court held that the National Traffic and Motor Vehicle Safety Act (NTMVSA) and associated regulations impliedly preempted state tort claims alleging that an automobile manufacturer had negligently designed a car without a driver's side airbag.234 While the Court rejected the argument that the NTMVSA expressly preempted the state law claims,235 it reasoned that the claims interfered with the federal objective of giving car manufacturers the option of installing a "variety and mix" of passive restraints.236 The Court discerned this goal from, among other things, the history of the relevant regulations and Department of Transportation (DOT) comments indicating that the regulations were intended to lower costs, incentivize technological development, and encourage gradual consumer acceptance of airbags rather than impose an immediate requirement.237 The Court accordingly held that the NTMVSA impliedly preempted the state law claims because they conflicted with these federal goals.238

However, the Court has rejected the argument that federal automobile safety standards impliedly preempt all state tort claims concerning automobile safety. In Williamson v. Mazda Motor of America, Inc., the Court held that a different federal safety standard did not preempt a state law claim alleging that a carmaker should have installed a certain type of seatbelt in a car's rear seat.239 While the regulation at issue in Williamson allowed manufacturers to choose between a variety of seatbelt options, the Court distinguished the case from Geier on the grounds that the DOT's decision to offer carmakers a range of choices was not a "significant" regulatory objective.240 Specifically, the Court reasoned that because the DOT's decision to offer manufacturers a range of options was based on relatively minor design and cost-effectiveness concerns, the state tort action did not conflict with the purpose of the relevant federal regulation.241

Example: Federal Civil Rights

The Court has also held that state law can pose an obstacle to federal goals where it impedes the vindication of federal rights. In Felder v. Casey, the Court held that 42 U.S.C. § 1983 (Section 1983)—which provides individuals with the right to sue state officials for federal civil rights violations—preempted a state statute adopting certain procedural rules for bringing Section 1983 claims in state court.242 Specifically, the state statute required Section 1983 plaintiffs to provide government defendants 120 days' written notice of (1) the circumstances giving rise to their claims, (2) the amount of their claims, and (3) their intent to bring suit.243 The Court held that federal law preempted these requirements because the "purpose" and "effect" of the requirements conflicted with Section 1983's remedial objectives.244 Specifically, the Court reasoned that the requirements' purpose of minimizing the state's liability conflicted with Section 1983's goal of providing relief to individuals whose constitutional rights are violated by state officials.245 Moreover, the Court concluded that the state statute's effects interfered with federal objectives because its enforcement would result in different outcomes in Section 1983 litigation based solely on whether a claim was brought in state or federal court.246

Conclusion

The Supreme Court has held that state law can conflict with federal law in a number of ways. First, state law can conflict with federal law when it is physically impossible to comply with both sets of laws. While the Court has characterized this type of impossibility preemption argument as a "demanding defense,"247 its decisions in PLIVA and Bartlett arguably extended the doctrine's scope.248 In those cases, the Court made clear that impossibility preemption remains a viable defense even in instances in which a regulated party can petition the federal government for permission to comply with state law249 or stop selling a regulated product altogether.250

State law can also conflict with federal law when it poses an "obstacle" to federal goals. In evaluating congressional intent in obstacle preemption cases, the Court has relied upon statutory text,251 structure,252 and legislative history253 to determine the scope of a statute's preemptive effect. Relying on these indicia of legislative purpose, the Court has held that state laws can pose an obstacle to federal goals by interfering with a uniform system of federal regulation,254 imposing stricter requirements than federal law (where federal law evinces an intent to establish a regulatory "ceiling"),255 or by impeding the vindication of a federal right.256

While obstacle preemption has played an important role in the Court's preemption jurisprudence since the mid-20th century, recent developments may result in a narrowing of the doctrine. Indeed, commentators have noted the tension between increasingly popular textualist theories of statutory interpretation—which reject extra-textual evidence as a possible source of statutory meaning—and obstacle preemption doctrine, which arguably allows courts to consult such evidence.257 Identifying this alleged inconsistency, Justice Thomas has categorically rejected the Court's obstacle preemption jurisprudence, criticizing the Court for "routinely invalidat[ing] state laws based on perceived conflicts with broad federal policy objectives, legislative history, or generalized notions of congressional purposes that are not embodied within the text of federal law."258

The Court's recent additions may also presage a narrowing of obstacle preemption doctrine, as some commentators have characterized Justices Gorsuch and Kavanaugh as committed textualists.259 Indeed, the Court's 2019 decision in Virginia Uranium, Inc. v. Warren suggests that Justices Gorsuch and Kavanaugh may share Justice Thomas's skepticism toward obstacle preemption arguments.260 In that case, Justice Gorsuch authored an opinion joined by Justices Thomas and Kavanaugh in which he rejected the proposition that implied preemption analysis should appeal to "abstract and unenacted legislative desires" not reflected in a statute's text.261 While Justice Gorsuch did not explicitly endorse a wholesale repudiation of what he characterized as the "purposes-and-objectives branch of conflict preemption," he emphasized that any evidence of Congress's preemptive purpose must be sought in a statute's text and structure.262