Introduction

Founded in 1961, the Peace Corps sends American volunteers to serve at the grassroots level in villages and towns across the world. The Peace Corps' three-point legislative mandate, unchanged since its founding, is to promote world peace and friendship by improving the lives of those they serve, help others understand American culture, and bring volunteers' experience back to Americans at home. To date, more than 235,000 Peace Corps volunteers have served in 141 countries.1 As of the end of September 2018, 7,367 volunteers were serving in 61 nations.2 The current Director of the Peace Corps is Jody Olsen, who was sworn into office in March 2018.

In 2019, the 116th Congress may consider the President's FY2020 funding request for the Peace Corps, reauthorization of the Peace Corps, oversight of reforms related to the Farr-Castle Act, the geographic distribution of Peace Corps programs, and related issues.

|

|

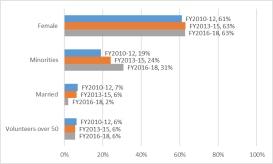

Source: Peace Corps, Congressional Budget Justification, FY2010-18. Notes: Percentages are three-year averages. |

Agency Overview

The Volunteer Force

The volunteer force is considered the core of the Peace Corps and the primary conduit to achieve its three goals. Congress has historically taken interest in the extent to which Peace Corps attracts strong ambassadors for American values, provides technical experts of use for countries' development, and attracts volunteers who reflect American society.3 In FY2018, 32% of volunteers were minorities, a marked increase from prior years; 64% of volunteers were women; and 99% were single (see Figure 1). The median age was 25, consistent with past years.4 About 85% of volunteers have historically been recent college graduates with a "generalist" background.5

Volunteers come from every U.S. state; on a per capita basis (number of volunteers per 100,000 residents), the top providers of volunteers in FY2018 were the District of Columbia, Vermont, Montana, Oregon, Virginia, Maryland, New Hampshire, Maine, Colorado, Rhode Island, Washington, and Minnesota.6

|

|

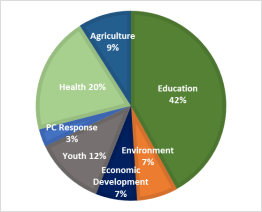

Source: Peace Corps FY2018 Agency Financial Report. |

Programs

The Peace Corps maintains two types of volunteer programs: the traditional Peace Corps tour and Peace Corps Response.

About 98% of volunteers serve in the traditional 27-month tour, including three months of language, technical, and cultural training followed by 24 months of service.7 Peace Corps volunteers work in a range of sectors (see Figure 2), many of which align with the development sectors of other foreign assistance programs.

In 1996, Peace Corps introduced the Peace Corps Response Program (formerly Crisis Corps), which draws on "returned" (i.e., former) volunteers (RPCVs) and, since 2012, those with specialist professional backgrounds who have never been volunteers. Response volunteers carry out short-term (three-month to one-year) emergency, humanitarian, and development assignments at the community level with nongovernmental relief and development organizations. To date, more than 3,400 Peace Corps Response volunteers have served in 80 countries, including post-earthquake Haiti and other disaster-affected countries. Of that total amount, in FY2018, 196 Peace Corps Response volunteers served across 30 countries.

|

|

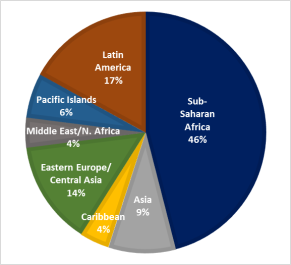

Source: Peace Corps FY2018 Agency Financial Report. |

Countries of Service

Almost half of the volunteer force serves in sub-Saharan Africa (see Figure 3). The countries with the highest number of volunteers currently are Ukraine, Zambia, Senegal, Mozambique, Tanzania, Paraguay, Morocco, and Panama. Political instability and safety concerns preclude a larger volunteer presence in the Middle East/North Africa. New programs have often coincided with improvement in U.S. relations with new partner countries, such as in Vietnam and Myanmar. Both programs were announced in the wake of visits by then-President Obama, underlining a significant warming of relations with the United States for both countries. Volunteers have since begun service in Myanmar, but the Vietnam program has yet to launch.

Recent Legislative and Executive Actions

As the Peace Corps commemorated the 50th anniversary of its founding in 2011, an evaluation of the Peace Corps' organizational approach and concurrent reports of inadequate protocols for volunteer safety intensified congressional scrutiny of the agency. The resulting reforms have dominated the agency's strategic direction over the past decade, and Congress continues to take an active role in facilitating these ongoing changes.

Peace Corps Agency Assessment

In 2009, Congress initiated a comprehensive assessment of the Peace Corps' operational model. The resulting recommendations, released in 2010, precipitated a series of sweeping reforms that continue partly to define the agency's policy agenda today.8 To foster a metrics-oriented programming approach, the agency established a formal annual portfolio review of all active country programs, created specific criteria for entry into new countries, and enacted a new monitoring and evaluation policy with standard indicators across countries.9 To increase staff effectiveness, the agency instituted a reorganization of country desk positions, a results-oriented performance appraisal program, and an extension of tour lengths to five years from the original 30 months. The Peace Corps enacted further reforms to volunteer training, Peace Corps Response, the recruitment process, and returned volunteer activities (so-called "Third Goal" programs, for the third of Peace Corps' three-part legislative mandate). Each of these reforms is discussed in detail below under "Issues."

Kate Puzey Act of 2011

In the midst of the assessment team's work, the ABC television newsmagazine 20/20 in 2010 reported on multiple episodes of rape against Peace Corps volunteers, as well as the 2009 murder of volunteer Kate Puzey in Benin. The stories featured on 20/20 catalogued some Peace Corps staff breaching confidentiality, failing to respond to volunteer reports of threatening behavior, lacking compassion for victims or their parents, and blaming victims for crimes inflicted upon them.

Earlier, the agency had taken some steps to confront the sexual assault of volunteers. The Peace Corps established a Sexual Assault Working Group in 2008, and the Peace Corps Director followed up by issuing a formal Commitment to Sexual Assault Victims in response to victims' complaints. Volunteer advocates responded that the Director's commitments were not sufficient. They pushed for stronger actions to reduce assault incidents and better address the needs of victims where assaults occur, including legislation.10 In 2011, several pieces of legislation were introduced in the House and Senate that sought to answer this call, resulting in the Kate Puzey Peace Corps Volunteer Protection Act of 2011 (the Puzey Act, P.L. 112-57). Provisions of the legislation are discussed in the Issues section under "Sexual Assault."

Sam Farr and Nick Castle Peace Corps Reform Act of 2018

The Peace Corps has generally been lauded for its implementation of the Puzey Act, but scrutiny of volunteer sexual assault persisted and widened to other areas of volunteer health and safety. The 2013 death of Peace Corps/China volunteer Nicholas Castle, resulting from what the Inspector General (IG) determined was a series of medical misdiagnoses and treatment failures,11 led to a renewed push for reforms.

The House and Senate in the 115th Congress concurrently considered two parallel bills. The Senate passed S. 2286 (the Nick Castle Peace Corps Reform Act of 2018) on March 13, 2018, which focused on volunteer health care and agency operations. A House bill, H.R. 2259 (the Sam Farr Peace Corps Enhancement Act), focused on volunteer safety and security concerns and post-service disability and health care. The two bills were combined into the Sam Farr and Nick Castle Peace Corps Reform Act of 2018 which was signed into law on October 9, 2018 (the Farr-Castle Act, P.L. 115-256).

The enacted law further strengthened several of the provisions of the Puzey Act, established new policies for volunteer health care, added several exceptions to the "Five Year Rule," and adjusted reporting requirements regarding country program planning and closure. These items are further addressed in respective sections under "Issues."

Peace Corps Strategic Plan: FY2018-FY2022

The Peace Corps Strategic Plan for the period FY2018 to FY2022 poses six strategic and management objectives meant to further the three long-standing goals of the Peace Corps Act.12 Each objective is associated with performance goals and progress benchmarks, the results of which are to be published annually. For example, the objective of promoting sustainable change in the communities where volunteers work is measured by the percentage of projects with documented gains in community-based development outcomes. Underlying that indicator are efforts made in recent years to describe and document expected volunteer contributions to host community development goals. Another indicator of sustainable change performance will be the result of annual impact studies, an innovation launched in 2008 and used to develop best practices for agency programs.

Other objectives are to enhance volunteer effectiveness (indicators include improved language learning, an improved site management system, and strengthened project planning); optimize volunteer resilience (indicators include increasing volunteer capacity to manage adjustment challenges and efforts to establish realistic expectations of service); build leaders for tomorrow (measured in part by the number of opportunities for RPCVs to engage in continued service); improve agency services; and proactively address agency risks through evidence-based decisionmaking (risks including safety and security of volunteers, risks to IT infrastructure, and emergency preparedness and response).

Funding Trends and FY2020 Appropriations

The Peace Corps' funding, provided through the State, Foreign Operations and Related Programs (SFOPS) appropriation, has remained approximately $410 million since 2016, with a $0.2 million increase in FY2019. Volunteer levels have been relatively static for the first two years of the Trump Administration. While consecutive budget requests from the President have proposed Peace Corps budget cuts of approximately 3%, those cuts were proportionately less than cuts proposed for the wider State-Foreign Operations budget.

|

Fiscal Year |

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

|

Request (current $ mil.) |

446.2 |

439.6 |

374.5 |

378.8 |

380.0 |

410.0 |

410.0 |

398.2 |

396.2 |

396.2 |

|

Appropriation (current $ mil.) |

374.3 |

375.0 |

356.0 |

379.0 |

379.5 |

410.0 |

410.0 |

410.0 |

410.2 |

— |

|

Total Volunteers |

9,095 |

8,073 |

7,209 |

6,818 |

6,919 |

7,213 |

7,376 |

7,367 |

— |

— |

Sources: Peace Corps and CRS.

Notes: Figures reflect across-the-board rescissions and supplemental appropriations; they do not count transfers. Total volunteers are number at end of the fiscal year. Volunteer numbers include those funded by both Peace Corps appropriations as well as transfers from other agencies, such as the State Department President's Emergency Program for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR). In FY2018, 735 volunteers were funded by PEPFAR through a funding transfer, an amount not included in the table.

The Trump Administration's FY2020 budget request included $396.2 million for the Peace Corps, a 3.5% cut from the appropriated FY2019 level (P.L. 116-6, Division F, Title III) and the same as its FY2019 request. The Administration claims that the request would support a volunteer force of roughly 7,500.13 On June 19, 2019, the House approved a multi-bill appropriations measure that provided $425 million for the Peace Corps, a 3.6% increase from FY2019 (H.R. 2740, which included SFOPS). A companion bill in the Senate has yet to be introduced as of June, 2019.

Issues

Congress has historically worked closely with the Peace Corps to chart its strategic direction, and the 116th Congress faces multiple issues to guide the Peace Corps' future. The 116th Congress will oversee implementation of reforms recently enacted to address volunteer safety and health care. It may also consider several issues that have not seen legislative action in some time, including the Peace Corps' budget and potential reauthorization, recruitment and training, volunteer benefits, Peace Corps' strategic partnerships, and so-called "Third Goal" activities.

Budget and Expansion

In 1985, Congress made it the policy of the United States to maintain a Peace Corps volunteer force of at least 10,000 individuals,14 consistent with volunteer levels in the 1960s. Although levels have increased since the 1980s, the Peace Corps has not reached the 10,000 volunteer goal since it was enacted. Presidents Clinton, Bush, and Obama each recommitted to reaching that goal and submitted budget requests to achieve it. Congress has weighed whether sufficient funds were available to reach those levels vis-à-vis other priorities, and has expressed concern about the agency's ability to manage a larger volunteer force (see "Programming and Support," below).15 The FY2018 to FY2022 Peace Corps Strategic Plan does not mention a specific goal for volunteer levels.

|

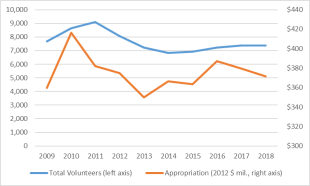

Figure 4. Peace Corps Volunteer Levels and Appropriations, 2009-2018 |

|

|

Source: Peace Corps Agency Financial Reports. Notes: Appropriations are in constant 2012 dollars. |

Volunteer levels peaked in 2011 at 9,095 after a historic funding increase in FY2010. Appropriations have since been stagnant, and FY2018 funding is more than 10% lower than the inflation-adjusted peak in FY2010. Volunteer levels have dropped off accordingly, settling around 7,000—a decline of about a sixth from its 2011 peak (see Figure 4). The National Peace Corps Association suggested in 2017 that achieving a 10,000 volunteer level by FY2022 would require an appropriation of $600 million, a nearly 50% increase over current levels and far less than the Trump Administration's requests.16

Authorization Legislation

Despite repeated efforts during the past decade, Congress has not enacted a new Peace Corps funding authorization. The last such Peace Corps authorization (P.L. 106-30), approved in 1999, covered the years FY2000 to FY2003. In 2017, H.R. 3130 included an authorization for the Peace Corps, but it was not reported out of committee. The last time a Peace Corps authorization bill saw floor action was in 2012, when H.R. 6018 passed the House but was not taken up in the Senate. Appropriations bills routinely waive the requirement of authorization of appropriations for foreign aid programs, as in the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2019 (§7022).

Volunteer Expertise and Training

The Peace Corps, while adept at recruiting generalists and training them sufficiently to carry out useful assignments, has historically not prioritized attracting highly skilled professionals.17 This approach has long been a source of debate. Some have argued that the Peace Corps should recruit more experienced specialists to meet the growing demands of a complex world for technical experts, such as doctors, agronomists, or engineers. Weighed against this view is the belief that the Peace Corps is as much an agency of public diplomacy as a development organization. Advocates of this view argue that demonstration of U.S. values through personal interaction is as important as technical assistance, and recent college graduates may be less resource-intensive to recruit and manage.

The 2010 Comprehensive Agency Assessment team determined that career, family, and personal obligations naturally limit the number of older specialists interested in Peace Corps service. The team recommended that the Peace Corps embrace the generalist character of its volunteers and strengthen their capabilities through better training and more focused programs. The Peace Corps' resulting "Focus in/Train up" initiative reduced programs' breadth and strengthened technical training for the remaining areas. Since 2010, Peace Corps has reduced the number of technical programs by at least 24% and extended preservice training by about one week.18 To accomplish this, Peace Corps has both reduced its geographic footprint and tightened its technical focus in some countries. Peace Corps' program portfolio has declined from 69 countries in 2009 to 61 in 2018, and the agency has terminated certain country technical programs—agriculture programs have been withdrawn from several Latin American countries, for example, while other countries with growing English proficiency, such as Botswana, Costa Rica, and Ecuador, have ended their education programs.

The assessment team also recommended continued efforts to recruit experienced and skilled volunteers. The team identified Peace Corps Response as a useful, flexible channel to accommodate older volunteers' obligations with shorter or less remote assignments. The Peace Corps has maintained the program's flexible time commitments, and Peace Corps Response is active in both traditional Peace Corps countries and those without a standard Peace Corps presence. The agency expanded eligibility in 2012 to candidates without prior Peace Corps experience.

Challenges remain. The Peace Corps launched the Global Health Services Partnership in 2013 for doctors and nurses to serve as adjunct faculty in medical schools overseas, but closed the program in 2018. Peace Corps Response has remained approximately 3% of all volunteers in recent years, suggesting it is a stable stream for older volunteers but not a growth source for nontraditional volunteers. Given the agency's limited resources, this may reflect a continuing strategic decision to concentrate on Peace Corps' deep relationship with colleges in recruiting fresh graduates for the program, and the recognition that Peace Corps Response is likely to remain a useful but ultimately secondary component of the volunteer force.

Volunteer Recruitment

Whatever the skill sets and demographic characteristics sought by the agency, the recruitment of high-quality volunteers willing to live in unfamiliar and sometimes uncomfortable conditions is essential to the overall mission of the Peace Corps. A substantial spike in applicants after the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks has made it easier for the Peace Corps to meet its recruitment goals, but concerns continued to arise about the duration and lack of transparency of the recruitment process.

As part of the reforms initiated from the 2010 agency assessment, the Peace Corps has sought to streamline recruitment and strengthen diversity outreach, yielding significant results. Minority representation reached 32% in 2018 (see Figure 1 above). The Peace Corps introduced a new online application platform, a new medical clearance review system, and a significantly streamlined application form. The agency also now allows applicants to choose their country and sector of service. The number of applications for the two-year volunteer program rose to a 40-year high of 20,935 in FY2017.19

Programming and Support

The Peace Corps has been criticized in the past for providing inadequate programming and support of volunteers. Reports in the past observed that some volunteers had little or nothing to do, characterizing the agency as failing to plan, evaluate, and monitor volunteers.20 While most volunteers rate their overall experience highly, about 20% of volunteers in 2018 reported they did not have enough to do at their work site, and 23% were dissatisfied with support received from Peace Corps staff in site selection and preparation.21 Chronic shortcomings include ineffective volunteer training, poor site development practices, inadequately implemented safety and security procedures, and limited coordination with country ministries and project partners.22 Of the FY2015 volunteer cohort, 21% resigned prior to completing their term, a sign of dissatisfaction that has steadily increased since FY2012.23

The Peace Corps has recently established systematic approaches to project development, annual project reviews, and increased opportunities for site visits and volunteer feedback. The agency has also analyzed volunteer satisfaction with site selection and preparation, identifying its top five drivers as (1) community members being prepared for the volunteer's arrival, (2) work being meaningful, (3) work matching the volunteer's skills, (4) sufficient work being available, and (5) work reflecting community needs. As the agency has become more data-driven, it is trying to quantify these points and measure progress toward achieving them.24 The Farr-Castle Act requires the Peace Corps to continue administering the annual volunteer survey, mandates its public release, and requires that country programs take volunteer feedback into account as they develop their country performance plans.

Safety and Security

The safety and security of Peace Corps volunteers has long been a prime concern for Congress, and attention has grown in recent years, as noted above. Since its creation, 301 volunteers have died in service, though incidents have declined since the 1970s. The top cause of volunteer death has long been motor vehicle accident, with disease and drowning also major causes.25 In the wake of the 9/11 terrorist attacks, the Peace Corps established a standalone Safety and Security Office to better coordinate physical risk mitigation efforts worldwide.26 Yet a 2010 IG report cited multiple shortcomings in its safety and security program, though it noted significant improvements over recent years.27 The IG criticized a lack of effective processes, standardized training, and skilled personnel to manage and implement discrete aspects of the Peace Corps' safety and security programs. The IG also found numerous instances of recurring evaluation findings.28

The 2010 IG report made 28 recommendations. Among them were that the Office of Safety and Security establish clear lines of authority to manage its work, and enact a training program for Officers and Coordinators. It also advised the Peace Corps to adequately track the office's recommendations. The IG recommended Peace Corps provide volunteers a safety handbook during recruitment and staging and require them to sign a code of conduct on basic security principles before departure. The IG also recommended the Peace Corps establish a formal agreement with the Department of State's Bureau of Diplomatic Security to clarify the roles of each agency.29 By July 2012, the Peace Corps had implemented all of these recommendations. In 2018, the annual volunteer survey reported that 92% of volunteers felt "safe" or "very safe" where they live, and 95% where they work.30

The Peace Corps has further responded to ongoing concerns about the threats of terrorism, natural disasters, and civil strife by upgrading communications protocols and security measures, and by updating country-specific Emergency Action Plans (EAP) annually. EAPs define roles and responsibilities for staff and volunteers, explain standard policies and procedures, and list emergency contact information for every volunteer.

Volunteer safety has remained an active issue for Congress. The Farr-Castle Act of 2018 enacted several reforms; among them, it mandates consultation with the IG on volunteer deaths and requires new notifications to volunteer candidates on safety and security considerations for their country assignment. An early draft of the Farr-Castle Act would have established procedures for prosecuting perpetrators of certain crimes against volunteers, but it was not enacted.

Sexual Assault

Sexual assault of volunteers continues to generate significant public and congressional attention. The 2011 Puzey Act has facilitated congressional oversight of these issues. Among other actions, the law

- requires the Peace Corps to submit an annual report to Congress on safety and security matters;

- specifies that volunteers receive sexual assault risk reduction and response training, including training tailored to the country of service, covering safety plans in the event of an assault, medical treatments available, medevac procedures, and information on the legal process for pressing charges;

- requires that sexual assault protocols and guidelines be developed and training be provided to staff regarding implementation;

- establishes alternative reporting systems for reports of sexual assault to ensure volunteer anonymity;

- establishes a victims advocate position to assist sexually assaulted volunteers and facilitate access to available services and a Sexual Assault Advisory Council to evaluate training and policy; and

- requires that the Peace Corps and State Department Bureau of Diplomatic Security agree to a memorandum of understanding on the duties and obligations of each with respect to protection of Peace Corps volunteers and staff.

In a series of reports on its implementation, the Peace Corps IG and the Sexual Assault Advisory Council have praised the Peace Corps for "markedly improved" support systems for addressing sexual assault and for commitment to Puzey Act mandates.31 An example cited by the IG was the training provided to all 27-month volunteers on best practices for sexual assault risk reduction and response.32

The Farr-Castle Act further advanced several of the Puzey Act mandates. It made the Office of Victim Advocacy permanent, integrating it into the Peace Corps' organizational structure, and extended and gave more investigative authority to the Sexual Assault Advisory Council.

Evacuations and Program Closures

Given that many volunteers serve in very remote, inaccessible locations,33 the Peace Corps often evacuates its volunteers more readily than other U.S. agencies with overseas operations. Since 2000, volunteers have been evacuated from at least 17 countries, and stability concerns have frustrated programs in several new countries. Most often, evacuations were due to political instability, crime, and civil unrest. Examples include the following:

- In sub-Saharan Africa, security crises have led to program suspensions in Mali and Niger, while the Burkina Faso and Kenya programs were suspended more recently due to ongoing security concerns. Programs in Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone were also temporarily suspended during the 2014 Ebola outbreak.

- In Central America, the Peace Corps withdrew from all Northern Triangle countries in 2011 over drug trafficking and gang violence. It has since returned to Guatemala.34 Nicaragua was evacuated in 2018 due to its ongoing political crisis.

- In the Europe and Central Asia region, the Peace Corps suspended its Kazakhstan program in 2011, reportedly due to the rape of several volunteers and terrorist attacks.35 The Peace Corps also suspended its program in Ukraine in 2014 due to the conflict with Russia there but has since returned. Azerbaijan's program ended in 2014 due to "lack of agreement with the host government."36

- In the Middle East and North Africa, the Peace Corps has scaled back its presence over safety concerns. A new Tunisia program was announced after the Arab Spring but was indefinitely suspended in 2013, following an attack on the U.S. Embassy and ongoing security uncertainties. The long-standing Jordan program was suspended in 2015 due to the "current regional environment," leaving Morocco the only remaining Peace Corps program in the region.

While security concerns have impeded Peace Corps' expansion in the Middle East, many Muslim-majority countries have active Peace Corps programs. In FY2016, about 16% of all volunteers served in countries with Muslim populations of over 40%, including in Indonesia, the most populous Muslim country in the world.37 Programs in East Asia have not been forced to evacuate in recent years, due to relative stability in that region.

Congress maintains interest in Peace Corps' geographic distribution. The Farr-Castle Act established a requirement of congressional notification by Peace Corps prior to entry or exit for any country program.

Volunteer Health Care

The Peace Corps provides serving volunteers with comprehensive health care, including routine care provided by a medical officer at each post and emergency care provided as deemed advisable, including medical evacuation to the United States. The agency has taken a number of steps in recent years to improve the quality of this care. To strengthen volunteer medical care, Peace Corps hired new Regional Medical Officers and established a Health Quality Improvement Council in response to the 2010 Agency Assessment. The agency now facilitates direct communication between volunteers and medical professionals at headquarters, has taken steps to improve the supervision and hiring of medical officers, initiated electronic medical records, and strengthened malaria prevention and treatment efforts, among other actions. The 2018 Volunteer Survey found 71% of volunteers were satisfied or very satisfied with medical support provided by the Peace Corps.38 IG reports reflect that some problems continue to occur, including inappropriate qualifications of medical officers and insufficient support to volunteers.

The Farr-Castle Act seeks to further improve volunteer health care by mandating periodic reports on implementation of several IG recommendations, establishing review procedures for all volunteer deaths, and requiring Peace Corps to report to Congress on progress on medical care reforms. It also requires new performance criteria for medical officer candidates and consultation with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on volunteer prescriptions, particularly for malaria prophylaxis.

Antimalarial Medication

With many volunteers serving in malaria-affected countries, medication and treatment of malaria is a recurring concern for volunteer health care. In March 2015, a former volunteer sued the Peace Corps for providing mefloquine, an antimalarial medication that may incur serious side effects, without appropriate warnings. The Peace Corps disputed this claim and noted that its policy is to monitor closely for tolerance and to offer changes in medication if requested.39 A 2017 joint study by Peace Corps and CDC researchers found that mefloquine had the highest adherence rate of all antimalaria medications prescribed by the Peace Corps, despite its side effects.40 In 2018, a volunteer in Comoros who had been prescribed Doxycycline, another antimalarial medication, died as a result of malaria infection, possibly after failing to take the medication daily.41 The Farr-Castle Act requires the Peace Corps to consult with experts at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention about best practices for antimalarial medications.

Post-Service Health Care

RPCVs with maladies attributable to their Peace Corps service have long complained of inadequate support from Peace Corps and considerable frustration trying to obtain the health services for which they are eligible. Former volunteers with volunteer-related health problems must file claims under the Federal Employees' Compensation Act (FECA) and work with the Department of Labor (DOL) Office of Workers' Compensation Programs (OWCP) to have those claims adjudicated. The Peace Corps itself is responsible for reimbursing DOL. The length and complexity of the established process, compounded by OWCP's perceived lack of understanding of volunteer service and the types of illnesses characteristic of work in developing nations, have elicited complaints from affected RPCVs.42

To address these concerns, the Peace Corps has hired staff to assist volunteers with their claims and attempted to shorten the claims process by working better with OWCP. In November 2015, a Healthcare Task Force, established by the Peace Corps, offered a set of actions based on 28 recommendations previously made by GAO, Peace Corps, and nongovernment interest groups. Among other steps, the Task Force suggested that the Peace Corps seek legislation to raise the ceiling on disability compensation, improve explanation of post-service health benefits to volunteers and RPCVs, and provide greater assistance to volunteers on post-service options regarding accessibility to insurance under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act.43 The Farr-Castle Act authorized the Peace Corps to provide medical care to returning volunteers for 120 days after termination of service for likely service-related conditions. While a version of the bill introduced in the House would have increased disability compensation and mandated a report on the disability claims process, neither of those provisions was included in the enacted law.

Volunteer Access to Abortion

Since 1979, annual appropriations measures that fund the Peace Corps have prohibited funds from being used to pay for abortions. Enacted appropriations measures from FY2015 through FY2019 have included exceptions for volunteers in cases of rape, incest, and when the mother's life is endangered. The exception provision as currently enacted must be repeated each year to remain in effect.44 Opponents of the exceptions argue that they constitute an expansion of abortion services by the federal government.45 Those in favor maintain that Peace Corps volunteers should have the same health benefits provided to other women on federal health care plans.46

Third Goal Activities

As part of the response to the 2010 assessment, the Peace Corps has sought to more fully and effectively address the so-called "third goal," the mandate that Peace Corps volunteers "help promote a better understanding of other peoples on the part of Americans." While this goal has consistently received less attention and funding than the agency's work abroad, the Peace Corps has broadened third goal efforts. Although funding remains relatively small (less than 0.3% of the FY2018 budget), the agency has established an Office of Third Goal and Returned Volunteer Services and expanded the Paul D. Coverdell World Wise Schools program, which connects volunteers with school classrooms throughout the United States.47

Post-Service Benefits

Upon completion of service, returned volunteers are entitled to several benefits, many of which are based on legislative mandates. Benefits include the following:

- Readjustment allowance: An allowance to facilitate a returned volunteer's "readjustment" to life after Peace Corps accrues monthly for the duration of a volunteer's service, one of the principal volunteer benefits Congress established in the Peace Corps Act of 1961.48 The readjustment allowance is currently $350/month,49 though its statutory minimum was set at $125/month in 1981.50 Several proposals were introduced in the 2000s to increase this minimum, most recently in the 110th Congress (H.R. 2410).

- Student loans: Volunteers are eligible for cancellation of up to 70% of their federal Perkins loans.51 However, the expiration of authority to issue new Perkins loans in October 2017 limits the applicability of that benefit moving forward. Volunteers may also count payments made during their service toward eligibility for the Public Service Loan Forgiveness Program.52 Legislation proposing changes to this program has recently been introduced in the 116th Congress in the Senate (S. 1203) and the House (H.R. 2441).

- Noncompetitive Eligibility (NCE): NCE allows federal agencies to hire volunteers without going through a competitive recruitment process for up to 12 months after a volunteer's completion of service.53 This benefit typically applies at the discretion of the agency. For example, the State Department has utilized NCE for civil service positions but not the Foreign Service.54

- Health insurance: Peace Corps provides transition health insurance for one month after a volunteer's termination of service. Volunteers can choose to extend their coverage for two months and have this paid out of their readjustment allowance.55 Peace Corps is meant to share information with departing volunteers about options for coverage after their service as well. Congress has considered investigating an extension of this benefit. A 2007 bill, S. 732, would have provided for a cost estimate to extend this health insurance to six months.

The Five-Year Rule

The five-year rule, which became law in August 1965 in an amendment to Section 7(a) of the Peace Corps Act, limits most Peace Corps staff to five years' employment. The rule does not apply to personal service contractors or foreign nationals.

The rule has been long discussed in the Peace Corps community and periodically addressed by Congress. The rule is seen to have had both positive and negative effects on the performance of the Peace Corps. Positive features may include that it

- creates a workforce generally perceived as vibrant, youthful, and energetic;

- permits the hiring of more returned volunteers due to high turnover (53% of all direct hires and 78% of overseas leadership posts between 2000 and 2010 were RPCVs), whose recent experience in the field provides high-quality policy input;

- generates a flow of staff departing for other international agencies that increases the influence of the Peace Corps on foreign policy;

- facilitates removal of poorly performing staff;

- provides a performance incentive for currently serving volunteers who might want to obtain employment in the agency; and

- creates possible cost savings from not accruing long-term salary and benefit obligations.

Negative features of the five-year rule largely derive from the higher turnover and short tenure of staff. Instead of a turnover of 20% each year, implied by the five-year rule, the actual rate is much higher—25% to 33% each year since 2004 according to the IG, quadruple that of the rest of the federal government. It is repeatedly noted as a cause of excessive personnel turnover in the IG's annual statement of management and performance challenges.56 These figures suggest that individuals are looking outside of the Peace Corps for more stable employment long before their term expires. The possible resulting negative impacts include

- poor institutional memory;

- frequent staffing vacancies;

- no long-term career incentives to encourage high performance;

- insufficient time for constantly departing staff to identify, develop, test, and implement innovative ideas;

- disincentive for management to invest in training and professional development;

- diminished management capacity, the rule being noted as a factor in multiple previous IG and GAO reports focusing on volunteer support, contract, and financial management; and

- high staff recruitment costs—costs strictly attributable to five-year rule turnover were estimated by the IG to be between 0.8% and 0.9% of the agency's budget from 2005 through 2009.

A 2012 IG evaluation made five broad recommendations to the Peace Corps, including that the Director should carry out reforms, including legislative remedies, to reduce the rate of turnover, increase length of employment, and identify which core functions suffer from turnover and develop processes to retain those personnel. However, the evaluation did not specify what those reforms might be.

The Peace Corps has since taken steps to mitigate the negative impacts of the five-year rule by leveraging several exceptions Congress established for the rule. The Peace Corps intends to broaden the use of one-year "special circumstances" extensions for U.S. direct hires. The Peace Corps has replaced its previous 30-month appointments with a full five-year appointment for new U.S. direct hires, and plans to use its statutory authority to reappoint up to 15% for an additional 30 months. While Peace Corps can only rehire staff after they have worked outside the agency as long as their previous appointment (to avoid workarounds to the five-year rule), the Farr-Castle Act allows the Director to designate "critical management support" staff for renewable appointments without the five-year limit. The Puzey Act also exempted the IG from the five-year rule.

The agency is also working to identify the causes of employee early resignation and the specific functions and positions where staff turnover is most harmful. Actions to date do not appear to have been successful, as the average length of employment has fallen from a 2013-2015 average of 4.2 years to 3.3 in 2016-17.57 In July 2017, the IG noted that recommendations on this issue had not yet been fully addressed by the Peace Corps.58

Partnerships

The Peace Corps has made efforts in recent years to build new partnerships with international organizations, U.S. government agencies, and others. In September 2012, the Peace Corps established its first global partnership with a corporation, Mondelez (formerly Kraft Foods), to support agriculture and community development. Volunteers also play a significant role in implementing presidential initiatives at the village level, partnering with the State Department and the U.S. Agency for International Development to advance presidential priorities. The Peace Corps takes part in the President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief, Feed the Future, and Let Girls Learn, and has announced plans to support President Trump's new Women's Global Development and Prosperity (W-GDP) initiative.59

Peace Corps Commemorative Site

In 2014, Congress authorized the creation of a Peace Corps commemorative site on federal land in the District of Columbia (P.L. 113-78). Through a process spearheaded by the Peace Corps Commemorative Foundation, a site near the U.S. Capitol Grounds was selected and the initial concept approved by the U.S. Commission of Fine Arts. However, a May 2, 2019, hearing before the National Capital Planning Commission raised concerns about both the concept design and the site selection and suggested revisiting an alternative site near the World Bank. The proposal is under review to address the issues raised. The Foundation intends to complete the project in 2021.