Introduction

Medicaid is a joint federal-state program that finances the delivery of primary and acute medical services, as well as long-term services and supports (LTSS), to a diverse low-income population, including children, pregnant women, adults, individuals with disabilities, and people aged 65 and older.

State participation in Medicaid is voluntary, although all states, the District of Columbia, and the territories1 choose to participate. States must follow broad federal rules to receive federal matching funds, but they have flexibility to design their own versions of Medicaid within the federal statute's basic framework. This flexibility results in variability across state Medicaid programs.

The federal government and the states jointly finance the Medicaid program. Federal Medicaid spending is an entitlement, with total expenditures dependent on state policy decisions and use of services by enrollees. Medicaid is an entitlement for both states and individuals. The Medicaid entitlement to states ensures that, so long as states operate their programs within the federal requirements, states are entitled to federal Medicaid matching funds. Medicaid also is an individual entitlement, which means that anyone eligible and enrolled in Medicaid under his or her state's eligibility standards is guaranteed Medicaid coverage.

In FY2018, Medicaid is estimated to have provided health care services to almost 75 million individuals at a total cost of $616 billion, with the federal government paying $386 billion of that total.2 In comparison, the Medicare program provided health care benefits to nearly 59 million individuals in that same year at a cost of roughly $711 billion.3

Medicaid provides a health care safety net for low-income populations,4 with approximately 21% of the U.S. population with Medicaid coverage in 2017.5 Medicaid plays a more significant role for certain subpopulations. For example, in 2017, Medicaid provided health coverage for 39% of all children in the United States;6 in the same year, it provided health coverage for 61% of all nonelderly individuals with income below 100% of the federal poverty level (FPL).7

For some types of services, Medicaid is a significant payer. For instance, in 2017, Medicaid accounted for about 44% of national spending on LTSS.8 Medicaid paid for 43% of all births in the United States in 2017.9 In FY2015, Medicaid accounted for 75% of public family planning expenditures (including federal, state, and local government spending).10

Medicaid was enacted in 1965 as part of the same law that created the Medicare program (the Social Security Amendments of 1965; P.L. 89-97). Medicaid was designed to provide coverage to groups with a wide range of health care needs that historically were excluded from the private health insurance market (e.g., individuals with disabilities who require LTSS or indigent populations in geographic locations where access to providers is limited). Because of the diversity of the populations that Medicaid serves, Medicaid offers some benefits that typically are not covered by major insurance plans offered in the private market (e.g., institutional and home and community-based LTSS or early and periodic screening, diagnosis, and treatment [EPSDT] services).

Medicaid also pays for Medicare premiums and/or cost sharing for low-income seniors and individuals with disabilities, who are eligible for both programs and referred to as dual-eligible beneficiaries. For other Medicaid enrollees, cost sharing (e.g., premiums and co-payments) generally are nominal, which may not be the case with coverage available through the private health insurance market. The Medicaid program pays for services provided by special classes of providers, such as federally qualified health centers (FQHCs), rural health clinics (RHCs), and Indian Health Service (IHS) facilities that provide health care services to populations in areas where access to traditional physician care may be limited.

This report describes the basic elements of Medicaid, focusing on who is eligible, what services are covered, how enrollees share in the cost of care, how the program is financed. The report also explains waivers, provider payments, and program integrity activities. At the end of the report is a section with additional Medicaid resources.

Eligibility

Eligibility for Medicaid is determined by both federal and state law, whereby states set individual eligibility criteria within federal minimum standards. As a result, there is substantial variability in Medicaid eligibility across states. Therefore, the ways that an individual might qualify for Medicaid are largely reflective of state policy decisions within broad federal requirements.

In general, individuals qualify for Medicaid coverage by meeting the requirements of a specific eligibility pathway offered by the state. Some eligibility pathways are mandatory, meaning all states with a Medicaid program must cover them; others are optional. Within this framework, states are afforded discretion in determining certain eligibility criteria for both mandatory and optional eligibility groups. In addition, states may apply to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) for a waiver of federal law to expand health coverage beyond the mandatory and optional eligibility groups specified in federal statute (see the "Medicaid Program Waivers" section for more information).

An eligibility pathway is the federal statutory reference(s) under Title XIX of the Social Security Act (SSA) that extends Medicaid coverage to one or more groups of individuals.11 Each eligibility pathway specifies the group of individuals covered by the pathway (i.e., categorical criteria), the financial requirements applicable to the group (i.e., financial criteria),12 whether the pathway is mandatory or optional, and the extent of the state's discretion over the pathway's requirements. Individuals in need of Medicaid-covered LTSS must demonstrate the need for long-term care by meeting state-based eligibility criteria for services, and they also may be subject to a separate set of Medicaid financial eligibility rules in order to receive LTSS coverage. All Medicaid applicants regardless of their eligibility pathway must meet federal and state requirements regarding residency, immigration status, and documentation of U.S. citizenship.13

Often an applicant's eligibility pathway dictates the Medicaid state plan services that a given program enrollee is entitled to (e.g., women eligible due to their pregnancy status are entitled to Medicaid pregnancy-related services). When applying to Medicaid, an individual may be eligible for the program through more than one pathway. In this situation, an individual is generally permitted to choose the pathway that would be most beneficial in terms of the treatment of income and sometimes assets when determining Medicaid eligibility, but also in terms of the available benefits associated with each eligibility pathway.

Medicaid eligibility determinations generally apply for 12 months before an eligibility redetermination must occur. Individuals may be retroactively eligible for Medicaid up to three months prior to the month of application, if the individual received covered services and would have been eligible had he or she applied during that period.14

The following sections describe Medicaid's categorical and financial eligibility criteria as well as additional eligibility requirements for Medicaid covered-LTSS.

Categorical Eligibility

Medicaid categorical eligibility criteria are the characteristics that define the population qualifying for Medicaid coverage under a particular eligibility pathway; in other words, the nonfinancial requirements that an individual must meet to be considered eligible under an eligibility group. Medicaid covers several broad coverage groups, including children, pregnant women, adults, individuals with disabilities, and individuals 65 years of age and older (i.e., aged). There are a number of distinct Medicaid eligibility pathways within each of these broad coverage groups.

Historically, Medicaid eligibility was limited to poor families with dependent children who received cash assistance under the former Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) program, as well as poor aged, blind, or disabled individuals who received cash assistance under the Supplemental Security Income (SSI) program. Medicaid eligibility rules reflected these historical program linkages both in terms of the categories of individuals who were served and in that the financial eligibility rules were generally based on the most closely related social program for the group involved (e.g., AFDC program rules for low-income families with dependent children and pregnant women, and SSI program rules for aged, blind, or disabled).15 Over time, Medicaid eligibility has expanded to allow states to extend Medicaid coverage to individuals beyond those who were eligible based on receipt of cash assistance, including the most recent addition of the ACA Medicaid expansion population (i.e., nonelderly adults with income up to 133% of FPL).16 Medicaid's financial eligibility rules also have been modified over time for certain groups.17

If a state participates in Medicaid, the following are examples of eligibility groups that must be provided Medicaid coverage:

- certain low-income families, including parents, that meet the financial requirements of the former AFDC cash assistance program;

- pregnant women with annual income at or below 133% of FPL;

- children with family income at or below 133% of FPL;

- aged, blind, or disabled individuals who receive cash assistance under the SSI program;18

- children receiving foster care, adoption assistance, or kinship guardianship assistance under SSA Title IV–E;

- certain former foster care youth;19

- individuals eligible for the Qualified Medicare Beneficiary program;20 and

- certain groups of legal permanent resident immigrants.21

Examples of eligibility groups to which states may provide Medicaid include the following:

- pregnant women with annual income between 133% and 185% of FPL;

- infants with family income between 133% and 185% of FPL;

- certain individuals who require institutional care and have incomes up to 300% of the SSI federal benefit rate;

- certain medically needy individuals (e.g., children, pregnant women, aged, blind, or disabled) who are otherwise eligible for Medicaid but who have incomes too high to qualify and spend down their income on medical care;22 and

- nonelderly adults with income at or below 133% of FPL (i.e., the ACA Medicaid expansion).23

|

Dual-Eligible Beneficiaries In CY2013, there were 10.7 million dual-eligible beneficiaries (individuals enrolled in both Medicare and Medicaid), which was 14.5% of Medicaid enrollment.24 Although commonly addressed as a single population, dual-eligible beneficiaries are diverse. While dual-eligible beneficiaries tend to be sicker and poorer than the Medicaid population as a whole, not all dual-eligible beneficiaries are in poor health. There are numerous Medicaid eligibility pathways for dual-eligible beneficiaries with different types of Medicaid coverage, but the two main categories of dual-eligible individuals are full dual-eligible beneficiaries and partial dual-eligible beneficiaries. Full dual-eligible beneficiaries receive full benefits from Medicare, and Medicaid provides them with full benefits in addition to financial assistance with their Medicare premiums and cost sharing. Partial dual-eligible beneficiaries receive full benefits from Medicare and financial assistance from Medicaid for Medicare premiums and cost sharing. In CY2013, there were 7.7 million full duals, with Medicaid spending totaling $116.8 billion, and 3.0 million partial duals, with $2.1 billion in Medicaid spending.25 |

Some individuals who are eligible for Medicaid are also eligible for Medicare. Individuals enrolled in both Medicaid and Medicare are referred to as dual-eligible individuals. For more information about this population, see the textbox entitled "Dual-Eligible Beneficiaries."

Financial Eligibility

Medicaid is also a means-tested program that is limited to those with financial need. However, the criteria used to determine financial eligibility—income and sometimes resource (i.e., asset) tests—vary by eligibility group.

For most eligibility groups the criteria used to determine eligibility are based on modified adjusted gross income (MAGI) income counting rules. There is no resource or asset test used to determine Medicaid financial eligibility for MAGI-eligible individuals.26

While MAGI applies to most Medicaid-eligible populations, certain populations such as older adults and individuals with disabilities are statutorily exempt from MAGI income counting rules. Instead, Medicaid financial eligibility for MAGI-exempted populations is based on the income counting rules that match the most closely related social program for the group involved (e.g., SSI program rules for aged, blind, or disabled eligibility groups). For MAGI-exempt eligibility groups, income disregards and assets or resource tests may apply.

Additional Eligibility Requirements for LTSS Coverage

Medicaid enrollees, many of whom qualify based on aged or disabled categorical criteria, may also have long-term care needs. In general, individuals in need of Medicaid-covered LTSS must also meet state-based functional and/or disease or condition-specific eligibility criteria. In other words, they must demonstrate the need for long-term care. There are certain pathways that establish eligibility to Medicaid-covered LTSS either for individuals receiving institutional care or for those who need the level of care provided in an institution and receive Medicaid-covered home and community-based services (HCBS).27 Most states offer HCBS under waiver programs that operate outside of Medicaid state plan requirements (see the "Medicaid Program Waivers" section for more information).

Applicants seeking certain Medicaid-covered LTSS are also subject to a separate set of Medicaid financial eligibility rules in order to receive such services (e.g., limits on the value of home equity, asset transfer rules). These additional financial rules attempt to ensure that program applicants apply their assets toward the cost of their care and do not divest them to gain eligibility sooner than would occur otherwise.

In addition, Medicaid specifies rules for equitably allocating income and assets to non-Medicaid-covered spouses for the purposes of determining LTSS coverage eligibility for nursing facility services and some HCBS. Commonly referred to as spousal impoverishment rules, these rules are intended to prevent the impoverishment of the spouse who does not need LTSS.28

Medicaid Enrollment

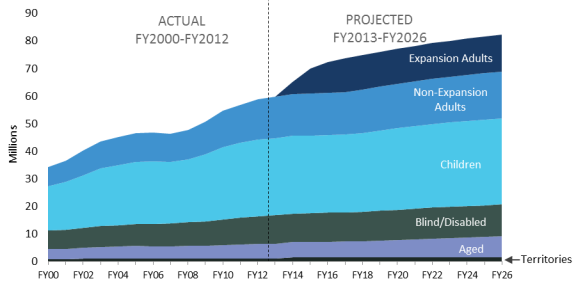

Figure 1 shows historical and projected Medicaid enrollment for FY2000 through FY2026. The figure shows steady enrollment growth, especially among nondisabled children and adults as a result of the recessions in the early and late 2000s.29 During periods of economic downturn, Medicaid programs face enrollment increases at a faster rate because job and income losses make more people eligible.

Since the implementation of the ACA Medicaid expansion in 2014, most of the growth in Medicaid enrollment is attributed to the expansion. Excluding the expansion adults, Medicaid enrollment was relatively flat due to low unemployment rates over the past couple years.30 For FY2017 through FY2026, the aged population is projected to be the fastest-growing Medicaid population due to baby boomers reaching the age of 65.31

Share of Enrollment Versus Expenditures, by Population

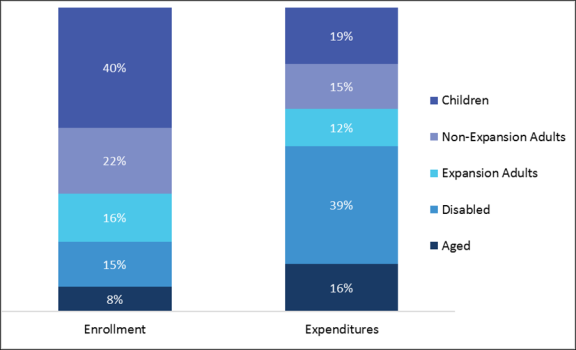

Different Medicaid enrollment groups have very different service utilization patterns. Larger enrollment groups account for a smaller proportion of Medicaid expenditures, while some smaller enrollment groups are responsible for a larger proportion of Medicaid expenditures. As shown in Figure 2, for FY2016, together Medicaid enrollment for children, non-expansion adults, and expansion adults comprised 77% of Medicaid enrollment but accounted for only 46% of Medicaid's total benefit spending. In contrast, together the disabled and aged populations represented about 23% of Medicaid enrollment but accounted for a larger share of Medicaid benefit spending (54%). While these statistics vary somewhat from year to year and state to state, the patterns described above generally hold true across years.

Benefits

Medicaid coverage includes a wide variety of preventive, primary, and acute care services as well as LTSS.32 Not everyone enrolled in Medicaid has access to the same set of services. An enrollee's eligibility pathway determines the available services within a benefit package. Federal law provides two primary benefit packages for state Medicaid programs: (1) traditional benefits and (2) alternative benefit plans (ABPs). Each of these packages is summarized in Table 1. For the medically needy subgroup, states may offer a more restrictive benefit package than is available to other enrollees. In addition, states can use waiver authority (e.g., SSA Section 1115) to tailor benefit packages to specified Medicaid subgroups as well as offer services outside traditional or ABP coverage, such as LTSS (see "Medicaid Program Waivers" for more information about Section 1115 waivers).

Table 1. Examples of Medicaid Mandatory and Optional Benefits for Traditional Benefits and Alternative Benefit Plans (ABPs)

|

Type of Benefit |

Traditional Benefits |

ABPs |

|

Mandatory |

|

|

|

Optional |

|

For special-needs subgroups, option to receive traditional benefits or enroll in an ABP plan. |

Sources: Title XIX of the Social Security Act and related federal guidance.

Notes: ABP = Alternative benefit plan

EPSDT = Early and periodic screening, diagnostic, and treatment services

FQHC = Federally qualified health center

In general, when Medicaid enrollees have other sources of insurance/payment (including Medicare), Medicaid is the payer of last resort. States can provide Medicaid coverage to individuals whose existing health insurance is limited (sometimes referred to as underinsured). In these cases, Medicaid wraps around that coverage (i.e., additional coverage for services covered under Medicaid but not under the other source of coverage).33

The following sections summarize Medicaid traditional benefits and ABPs. Then, there is a section comparing benefits included in traditional Medicaid coverage and those that are commonly included in ABPs.

Traditional Medicaid Benefits

Traditional Medicaid benefits include primary and acute care as well as LTSS. The traditional Medicaid program requires states to cover a wide array of mandatory services (e.g., inpatient hospital care, lab and x-ray services, physician care, nursing facility services for individuals aged 21 and older). In addition, states may provide optional services, some of which commonly are covered (e.g., personal care services, prescription drugs, clinic services, physical therapy, and prosthetic devices).

States define the specific features of each covered benefit within four broad federal guidelines:

- Each service must be sufficient in amount, duration, and scope to reasonably achieve its purpose. States may place appropriate limits on a service based on such criteria as medical necessity.

- Within a state, services available to the various population groups must be equal in amount, duration, and scope. This requirement is the comparability rule.

- With certain exceptions, the amount, duration, and scope of benefits must be the same statewide, referred to as the statewideness rule.

- With certain exceptions, enrollees must have freedom of choice among health care providers or managed care entities participating in Medicaid. (See "Service Delivery Systems" for information about managed care.)

The breadth of coverage for a given benefit can, and does, vary from state to state, even for mandatory services. For example, states may place different limits on the amount of inpatient hospital services a beneficiary can receive in a year (e.g., up to 15 inpatient days per year in one state versus unlimited inpatient days in another state)—as long as applicable requirements are met regarding sufficiency of amount, duration, and scope; comparability; statewideness; and freedom of choice. Exceptions to state limits may be permitted under circumstances defined by the state.

Alternative Benefit Plans

As an alternative to providing all the mandatory and selected optional benefits under traditional Medicaid, the Deficit Reduction Act of 2005 (DRA; P.L. 109-171) gave states the option to enroll state-specified groups in what was referred to as benchmark or benchmark-equivalent coverage but currently are called alternative benefit plans (ABPs).34 Under ABPs, states must provide comprehensive benefit coverage that is based on a coverage benchmark rather than a list of discrete items and services as under traditional Medicaid.

ABPs must qualify as either benchmark or benchmark-equivalent coverage. Under benchmark coverage, ABP benefits are at least equal to one of the statutorily specified benchmark plans (i.e., one of three commercial health insurance products, or a fourth "Secretary-approved" coverage option).35 Under benchmark-equivalent coverage, ABP benefits include certain specified services and the overall benefits are at least actuarially equivalent to one of the statutorily specified benchmark coverage packages.

Unlike traditional Medicaid benefit coverage, coverage under an ABP must include at least the essential health benefits (EHBs) that most plans in the private health insurance market are required to furnish.36 In addition, ABPs must include a variety of specific services, including services under Medicaid's early and periodic screening, diagnostic, and testing (EPSDT) benefit; family planning services and supplies; and both emergency and nonemergency transportation to and from providers. In general, the EHBs do not include LTSS. However, states may choose to include LTSS in their ABPs.

Under ABPs, states are permitted to waive the statewideness and comparability requirements that apply to traditional Medicaid benefits. This flexibility permits the state to define populations that are served and the specific benefit packages that apply. However, states that choose to implement the ACA Medicaid expansion are required to provide ABP coverage to the individuals eligible for Medicaid through the expansion (with exceptions for selected special-needs subgroups). Specific populations are exempt from mandatory enrollment in ABPs (e.g., those with special health care needs such as disabling mental disorders or serious and complex medical conditions). These individuals must be offered the option of a benefit plan that includes traditional Medicaid state plan services, which may include LTSS.

Comparing Traditional Medicaid Benefits to ABPs

It is difficult to draw comparisons about the ways in which traditional Medicaid benefits are similar to and different from ABP benefits, because the scope of each type of benefit package varies from state to state. This variability is largely a reflection of state choices in covering optional benefits, in addition to the mandatory Medicaid state plan benefits, as well as state choices for the base-benchmark for the EHBs that must be covered under ABPs.

However, differences in the federal laws regarding the scope of required benefits under traditional Medicaid and those required under ABPs highlight some common differences between the two types of benefits packages. For example, care in a nursing facility for individuals over the age of 21 is a required benefit under traditional Medicaid, whereas nursing home care is not a required benefit under ABPs.

Conversely, rehabilitative and habilitative services and devices, preventive and wellness services, and mental health and substance use disorder services are all required benefits under ABPs. By contrast, these APB benefit categories do not correspond to specific benefit categories under traditional Medicaid. Rather, services in these benefit categories could be covered under different benefit categories, such as physician services or physical, occupational, and speech therapy services.

To further illustrate this point, behavioral health (or any similar term) is not explicitly included among the required benefit categories under traditional Medicaid. Instead, most types of behavioral health benefits (e.g., the services of clinical psychologists and licensed clinical social workers and prescription drugs) are optional. By contrast, behavioral health benefits are mandatory under ABPs because "mental health and substance use disorder services, including behavioral health treatment" are included among the EHBs.

Medicaid Service Spending

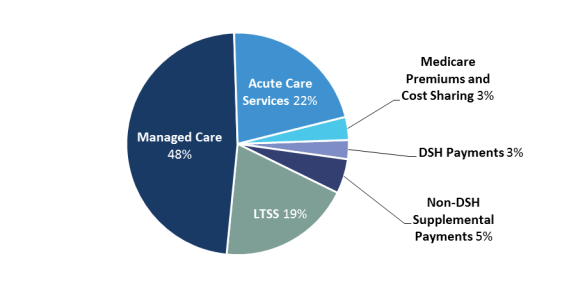

Figure 3 below shows the nationwide distribution of Medicaid expenditures across broad categories of service for FY2017. These data illustrate that 49% of benefit spending was for capitated payments under managed care arrangements (see "Service Delivery Systems" for information about managed care). The remaining 51% of benefit spending was FFS, and FFS spending on LTSS and acute care services accounted for 21% and 20%, respectively, of Medicaid benefit spending.

|

Figure 3. Medicaid Medical Assistance Expenditures, by Service Category (FY2018) |

|

|

Source: CRS analysis of CMS, CMS-64 Data (base expenditures), FY2018 as of April 29, 2019. Notes: Medical assistance expenditures exclude Medicaid expenditures for administrative activities. Managed care includes capitated payments under which Medicaid enrollees get most or all of their services through an organization under contract with the state (see "Service Delivery Systems" for information about managed care). Supplemental payments are Medicaid payments made to providers that are separate from and in addition to the standard payment rates for services rendered to Medicaid enrollees, and disproportionate share hospital (DSH) payments are one type of supplemental payments. Acute care services include prescription drugs. DSH = Disproportionate share hospital |

Beneficiary Cost Sharing

Federal statutes and regulations address the circumstances under which enrollees may share in the costs of Medicaid, both in terms of participation-related cost sharing (e.g., monthly premiums) and point-of-service cost sharing (e.g., co-payments [i.e., flat dollar amounts paid directly to providers for services rendered]).37 States can require certain beneficiaries to share in the cost of Medicaid services, but there are limits on (1) the amounts that states can impose, (2) the beneficiary groups that can be required to pay, and (3) the services for which cost sharing can be charged.38

In general, premiums and enrollment fees often are prohibited. However, premiums may be imposed on certain enrollees, such as individuals with incomes above 150% of FPL, certain working individuals with disabilities, and certain children with disabilities.

States can impose cost sharing at the point of service, such as co-payments,39 coinsurance,40 deductibles,41 and other similar charges, on most Medicaid-covered benefits up to federal limits that vary by income. Some subgroups of beneficiaries are exempt from cost sharing (e.g., children under 18 years of age and pregnant women).

The aggregate cap on participation-related cost sharing (e.g., monthly premiums) and point-of-service cost sharing (e.g., co-payments) is generally up to 5% of monthly or quarterly household income.42

In addition, beneficiaries receiving certain Medicaid-covered LTSS are required to apply their income exceeding specified amounts toward the cost of their care. These reductions from a beneficiary's income are referred to as post-eligibility treatment of income and are not subject to the 5% aggregate cost-sharing cap described above.43 The amounts a beneficiary may retain for their personal use vary by care setting (i.e., nursing facility versus home and community-based).

Service Delivery Systems

In general, most benefits for to Medicaid enrollees are delivered and paid for via two service delivery systems: fee-for-service (FFS) or managed care. Under the FFS delivery system, health care providers are paid by the state Medicaid program for each service provided to a Medicaid enrollee. Under the managed care delivery system, Medicaid enrollees get most or all of their services through an organization under contract with the state.

States traditionally have used the FFS service delivery model for Medicaid, but since the 1990s, the share of Medicaid enrollees covered by the managed care model has increased dramatically. Initially, states used managed care to deliver health care services to the healthiest Medicaid populations, including children and parents. However, recently, more states are turning to managed care for their aged and disabled populations.

There are three main types of Medicaid managed care:

- Comprehensive risk-based managed care—states contract with managed care organizations (MCOs) to provide a comprehensive package of benefits to certain Medicaid enrollees. States usually pay the MCOs on a capitated basis, which means the states prospectively pay the MCOs a fixed monthly rate per enrollee to provide or arrange for most health care services. MCOs then pay providers for services to enrollees.

- Primary care case management (PCCM)—states contract with primary care providers to provide case management services to Medicaid enrollees. Typically, under PCCM, the primary care provider receives a monthly case management fee per enrollee for coordination of care, but the provider continues to receive fee-for-service payments for the medical care services utilized by Medicaid enrollees.

- Limited benefit plans—these plans look like MCOs in that states usually contract with a plan and pay it on a capitated basis. The difference is that limited benefit plans provide only one or two Medicaid services (e.g., behavioral health or dental services).

As of July 1, 2017, about 82% of Medicaid enrollees were covered by some form of managed care.44 Two states (South Carolina and Washington) covered all Medicaid enrollees under managed care, and two states (Alaska and Connecticut) did not have any managed care coverage. The rest of the states use some combination of managed care and FFS coverage.45

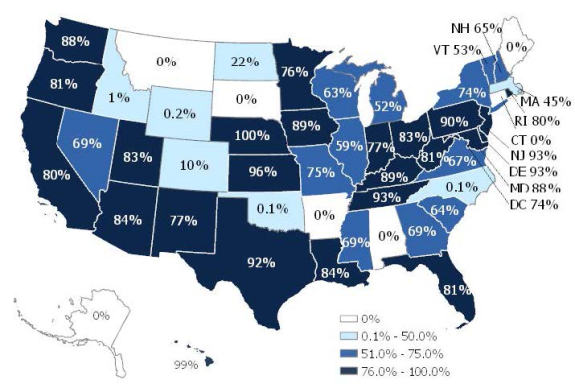

The most prevalent type of managed care is the comprehensive risk-based managed care that is provided through MCOs, with 69% of Medicaid enrollees with comprehensive risk-based managed care as of July 1, 2017.46 States' use of comprehensive risk-based managed care varies significantly, as shown in Figure 4.

Financing

The federal government and the states jointly finance Medicaid.47 The federal government reimburses states for a portion (i.e., the federal share) of each state's Medicaid program costs. Because federal Medicaid funding is an open-ended entitlement to states, there is no upper limit or cap on the amount of federal Medicaid funds a state may receive. In FY2018, Medicaid expenditures totaled $616 billion. The federal share totaled $386 billion and the state share was $230 billion.48

Federal Share

The federal government's share of most Medicaid expenditures is established by the federal medical assistance percentage (FMAP) rate, which generally is determined annually and varies by state according to each state's per capita income relative to the U.S. per capita income.49 The formula provides higher FMAP rates, or federal reimbursement rates, to states with lower per capita incomes, and it provides lower FMAP rates to states with higher per capita incomes.

FMAP rates have a statutory minimum of 50% and a statutory maximum of 83%.50 For a state with an FMAP of 60%, the state gets 60 cents back from the federal government for every dollar the state spends on its Medicaid program. In FY2019, FMAP rates range from 50% (14 states) to 76% (Mississippi).

The FMAP rate is used to reimburse states for the federal share of most Medicaid expenditures, but exceptions to the regular FMAP rate have been made for certain states (e.g., the District of Columbia and the territories), situations (e.g., during economic downturns), populations (e.g., the ACA Medicaid expansion population and certain women with breast or cervical cancer), providers (e.g., Indian Health Service facilities), and services (e.g., family planning and home health services). In addition, the federal share for most Medicaid administrative costs does not vary by state and is generally 50%.

While most federal Medicaid funding is provided on an open-ended basis, certain types of federal Medicaid funding are capped. For instance, federal disproportionate share hospital (DSH)51 funding to states cannot exceed a state-specific annual allotment. Also, Medicaid programs in the territories (i.e., American Samoa, Guam, Northern Mariana Islands, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands) are subject to annual spending caps.52

State Share

The federal government provides broad guidelines to states regarding allowable funding sources for the state share (also referred to as the nonfederal share) of Medicaid expenditures. However, to a large extent, states are free to determine how to fund their share of Medicaid expenditures. As a result, there is significant variation from state to state in funding sources.

States can use state general funds (i.e., personal income, sales, and corporate income taxes) and other state funds (e.g., provider taxes,53 local government funds, tobacco settlement funds, etc.) to finance the state share of Medicaid. Federal statute allows as much as 60% of the state share to come from local government funding.54 Federal regulations also stipulate that the state share not be funded with federal funds (Medicaid or otherwise).55 In state fiscal year 2017, on average, 72% of the state share of Medicaid expenditures was financed by state general funds, and the remaining 28% was financed by other state funds.56

Expenditures

The cost of Medicaid, like most health expenditures, historically increased at a rate significantly faster than the overall rate of U.S. economic growth, as measured by gross domestic product. In the past, much of Medicaid's expenditure growth has been due to federal or state expansions of Medicaid eligibility criteria, such as the ACA Medicaid expansion.

Medicaid expenditures are influenced by economic, demographic, and programmatic factors. Economic factors include health care prices, unemployment rates (see the "Medicaid Enrollment" section for a discussion of the impact of the unemployment rate on Medicaid enrollment, which also impacts expenditures), and individuals' wages. Demographic factors include population growth and the age distribution of the population. Programmatic factors include state decisions regarding optional eligibility groups, optional services, and provider payment rates. Other factors include the number of eligible individuals who enroll, utilization of covered services, and enrollment in other health insurance programs (including Medicare and private health insurance).

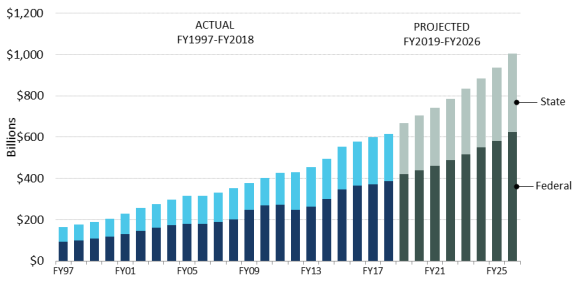

Figure 5 shows actual Medicaid expenditures from FY1997 to FY2017 and projected Medicaid expenditures from FY2018 through FY2026. These figures are broken down by state and federal expenditures. In FY2018, Medicaid spending on services and administrative activities in the 50 states, the District of Columbia, and the territories totaled $616 billion.57 Medicaid expenditures are estimated to grow to $1,006 billion in FY2026.58

Historically, in a typical year, the average federal share of Medicaid expenditures was about 57%, which means the average state share was about 43%. However, the federal government's share of Medicaid expenditures increased with the implementation of the ACA Medicaid expansion, because the federal government is funding a vast majority of the cost of the expansion through the enhanced federal matching rates.59 In FY2018, the average federal share of Medicaid is estimated to have been 62%, and it is expected to remain at that level through FY2026.60

With the implementation of the ACA Medicaid expansion in 2014, Medicaid expenditures increased 8.4% in FY2014 and 11.6% in FY2015.61 But since then, Medicaid expenditure growth has slowed; some reasons for this include slowing enrollment growth and managed care payment recoveries.62 However, the rate of growth for Medicaid expenditures is expected to increase starting in 2019 due in part to additional states implementing the ACA Medicaid expansion and price factors.63 This growth is expected to be somewhat offset by the reductions to Medicaid DSH allotments.64

Medicaid Program Waivers

The Social Security Act authorizes several waiver and demonstration authorities to provide states with the flexibility to operate their Medicaid programs. Waiver authorities permit states to disregard certain requirements and operate their programs outside of Medicaid rules. Each waiver authority has a distinct purpose and specific requirements. Under the various waiver authorities, states may try new or different approaches to the delivery of health care services or adapt their programs to the special needs of particular geographic areas or groups of Medicaid enrollees. The primary Medicaid waiver authorities include the following:

- Section 1115 Research and Demonstration Projects—SSA Section 1115 authorizes the HHS Secretary to waive Medicaid requirements contained in SSA Section 1902 (including but not limited to rules regarding freedom of choice of provider, comparability of services, and statewideness) and/or provide expenditure authority for expenditures that do not otherwise qualify for federal financial participation under SSA Section 1903 (referred to as costs not otherwise matchable) in order to permit states to conduct experimental, pilot, or demonstration projects that, in the judgment of the Secretary of HHS, are likely to assist in promoting the objectives of the Medicaid program. States use this waiver authority in a variety of ways, for example, to change eligibility criteria to offer coverage to new groups of people; to condition Medicaid eligibility on an enrollee's ability to meet work or other community engagement requirements; to provide services that are not otherwise covered, to offer different service packages or a combination of services in different parts of the state (e.g., coverage of nonelderly adults who are patients in institutions for mental disease);65 to cap program enrollment, and to implement innovative service delivery systems.

- Section 1915(b) Managed Care/Freedom of Choice Waivers—SSA Section 1915(b) authorizes the HHS Secretary to waive the freedom of choice of provider requirement to establish mandatory managed care programs or otherwise limit enrollees' choice of providers.66

- Section 1915(c) Home and Community-Based Services Waivers—SSA Section 1915(c) authorizes the HHS Secretary to waive requirements regarding comparability of services and statewideness in covering a broad range of HCBS (including services not available under the Medicaid state plan) for certain persons with LTSS needs. States also may waive certain income and resource rules applicable to persons in the community, which means that a spouse's or parent's income and, to some extent, resources are not considered available to the applicant for the purposes of determining Medicaid financial eligibility. States may use Section 1915(c) concurrently with other waiver authorities. For example, states may combine Sections 1915(b) and 1915(c) authorities to offer mandatory managed care for HCBS.

States often operate multiple waiver programs with their state plans. Key characteristics of these primary Medicaid waiver authorities compared with state plan requirements are summarized in Table 2. The statutory requirements that may be waived under each type of waiver are different, but all types of waivers are time limited and approvals are subject to reporting and evaluation requirements. In addition, all types of waivers must comply with various financing requirements (e.g., budget neutrality,67 cost-effectiveness,68 or cost-neutrality69).

Table 2. Key Characteristics of the Primary Medicaid Waiver Authorities Compared to State Plan Requirements

|

Key Characteristic |

§1115 Research and Demonstration Waivers |

§1915(b) Managed Care/Freedom of Choice Waivers |

§1915(c) Home and Community-Based Services (HCBS) Waivers |

Medicaid State Plan |

|

Number of Waivers (as of May 2019) |

60 waivers |

78 waivers (in 38 states and DC)b |

292 waivers (in 47 states and DC)b |

N/A |

|

Statewidenessc |

√ |

√ |

√ |

N/A |

|

Comparability of Servicesd |

√ |

√ |

√ |

N/A |

|

Freedom of Choice of Providere |

√ |

√ |

— |

N/A |

|

Income and Resource Rulesf |

— |

— |

√ |

N/A |

|

Federal Matching Funds for Costs Not Otherwise Matchable |

√ |

√ |

√ |

N/A |

|

Evaluations required |

√ |

√ |

√ |

N/A |

|

Duration |

5 year initial, generally renewed for up to 3-year intervals (or up to 10 years for non-complex waivers) |

2 year initial, renewed for up to 2-year intervals |

3 year initial, renewed for up to 5-year intervals |

Once approved duration indefinite |

|

Financing |

Budget neutral over the life of the program |

Must meet cost-effectiveness test |

Must meet cost-neutrality test |

Open-ended mandatory entitlement |

|

Enrollment caps and waiting lists permitted |

√ |

— |

√ |

Individual entitlement |

Source: Prepared by CRS based on program rules and regulations.

a. This waiver count identifies operational Section 1115 demonstration programs as posted on the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid (CMS) website, as of May 2019. Operational waivers are defined as Section 1115 waivers that have been granted CMS approval (and agreed upon by the state) for a current effective period as specified in the waiver Special Terms and Conditions (STCs), or as otherwise specified through a CMS waiver approval letter (e.g., a CMS approval letter that grants a temporary extension for all [or part] of the underlying demonstration waiver). This count may include waivers that are pending implementation as long as there is official documentation to show that the state has accepted the waiver conditions as outlined in the STCs and related documents (extension letters, amendment letters, etc.).

b. The waiver counts for Section 1915(b) and (c) waiver programs are the number of waivers listed as "active" on the CMS website as of May 2019.

c. Waiving the statewideness requirement (as permitted under §1902[a][1] of the Social Security Act [SSA]) allows states to target waivers to particular areas of the state where the need is greatest or where certain types of providers are available, for example.

d. Waiving comparability of services (SSA §1902[a][10][B]) allows states to target waiver services to particular groups of individuals or to target services on the basis of disease or condition.

e. Waiving the freedom of choice requirement (SSA §1902[a][23]) allows states to implement managed care delivery systems or otherwise limit choice of provider.

f. Waiving income and resource rules applicable to the community (SSA §1902[a][10][C][i][III])) means that a spouse's or parent's income and, to some extent, resources are not considered available to the applicant for the purposes of determining Medicaid financial eligibility.

g. States may seek CMS approval to provide expenditure authority for expenditures that do not otherwise qualify for federal financial participation under SSA §1903.

h. This waiver count provides the number of Section 1915(b) and (c) waiver programs listed as "active" on the CMS website.

Provider Payments

For the most part, states establish their own payment rates for Medicaid providers. Federal statute requires that these rates be consistent with efficiency, economy, and quality of care and sufficient to enlist enough providers so that covered benefits are available to Medicaid enrollees at least to the same extent they are available to the general population in the same geographic area.70 This is known as the equal access provision.

Provider payment reductions are a tool for states to manage Medicaid program costs. As a result, states' provider rate changes are often a function of the economy. For instance, during the most recent recession, which ended in 2009, many states reduced Medicaid provider payment rates due to budget pressures. However, over the past couple years, more states have been enhancing rather than reducing provider rates overall due to improvements in state finances.71 Low Medicaid provider payment rates in many states and their impact on provider participation have been perennial concerns for policymakers.72

In some cases, states make supplemental payments to Medicaid providers that are separate from, and in addition to, the payment rates for services rendered to Medicaid enrollees. Medicaid DSH payments are one type of supplemental payment, and federal statute requires that states make Medicaid DSH payments to hospitals treating large numbers of low-income patients.73 States also are permitted to make non-DSH supplemental payments to providers, but these payments must adhere to upper payment limits (UPLs) for certain institutional providers.74 The institutions subject to the UPL requirement are hospitals (separated into inpatient services and outpatient services), nursing facilities, intermediate care facilities for individuals with intellectual disabilities, and freestanding nonhospital clinics.75

Program Integrity

Program integrity initiatives are designed to combat fraud, waste, and abuse in the Medicaid program. Some oversight efforts focus on preventing fraud and abuse through effective program management, while others focus on addressing problems after they occur through investigations, recoveries, and enforcement activities.

Multiple agencies at the federal and state levels are involved in program integrity. The federal agencies are CMS, the Office of the Inspector General for the Department of HHS, the Department of Justice, and the Government Accountability Office. The state agencies involved with program integrity activities include the state Medicaid agencies and the federally required Medicaid Fraud Control Units (MFCUs). Coordination of Medicaid program integrity activities can be a problem because there are so many agencies working on such initiatives and each state develops its own approach to program integrity.76

The federal government and states contribute equally to fund most Medicaid activities to combat waste, fraud, and abuse, although for some activities the federal government provides additional funds through enhanced FMAP rates. As mentioned earlier, all states receive the same FMAP rate for administrative expenditures, including most program integrity activities, which generally is 50%. States receive higher FMAP rates for selected administrative activities, such as 90% for the startup of MFCUs and 75% for ongoing MFCU operation.

Additional Medicaid Resources

This section provides links to a number of Medicaid resources grouped by selected Congressional Research Service (CRS) products, other background resources, laws, regulations, and other information.

Selected CRS Products

- CRS In Focus IF10322, Medicaid Primer

- CRS Report R45412, Medicaid Alternative Benefit Plan Coverage: Frequently Asked Questions

- CRS Report R42640, Medicaid Financing and Expenditures

- CRS Report R43328, Medicaid Coverage of Long-Term Services and Supports

- CRS In Focus IF10399, Overview of the ACA Medicaid Expansion

- CRS Report R43847, Medicaid's Federal Medical Assistance Percentage (FMAP)

- CRS Report R43778, Medicaid Prescription Drug Pricing and Policy

- CRS Report R42865, Medicaid Disproportionate Share Hospital Payments

- CRS In Focus IF10422, Medicaid Disproportionate Share Hospital (DSH) Reductions

- CRS Report R45432, Medicaid Supplemental Payments

- CRS In Focus IF11012, Medicaid Funding for the Territories

- CRS In Focus IF10222, Medicaid's Institutions for Mental Disease (IMD) Exclusion

- Other CRS reports on Medicaid: https://www.crs.gov/search/#/?termsToSearch=medicaid

Laws

Most federal Medicaid law is in SSA Title XIX (as amended):

https://legcounsel.house.gov/Comps/Social%20Security%20Act-TITLE%20XIX(Grants%20to%20States%20for%20Medical%20Assistance%20Programs).pdf

SSA Title XIX is codified in the U.S. Code (42 U.S.C. §1396-1396w-5):

http://uscode.house.gov/view.xhtml?path=/prelim@title42/chapter7/subchapter19&edition=prelim

SSA Title XI has several general provisions relevant to Medicaid, including, for example, provisions on demonstration projects, the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation, quality measures, and program integrity:

https://legcounsel.house.gov/Comps/Social%20Security%20Act-TITLE%20XI(General%20Provisions,%20Peer%20Review,%20and%20Administrative%20Simplification).pdf

SSA Title XI is codified in the U.S. Code (42 U.S.C. §§1301-1320e-3):

http://uscode.house.gov/view.xhtml?path=/prelim@title42/chapter7/subchapter11&edition=prelim

The entire SSA, as amended, is also available in a compilation from the House Office of Legislative Counsel

https://legcounsel.house.gov/Comps/SSA-merged.pdf

Regulations

Most federal Medicaid regulations are in Title 42 of the Code of Federal Regulations (42 C.F.R. §§430.0-456.725):

https://www.ecfr.gov/cgi-bin/text-idx?c=ecfr&tpl=/ecfrbrowse/Title42/42cfrv4_02.tpl

In addition to federal laws and regulations, CMS issues sub-regulatory program guidance through publications such as

- informational bulletins and letters to State Medicaid Directors

https://www.medicaid.gov/federal-policy-Guidance/index.html - the State Medicaid Manual

https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/Paper-Based-Manuals-Items/CMS021927.html - frequently asked questions

https://www.medicaid.gov/faq/index.html

More Information

- Medicaid is administered at the federal level by CMS in HHS:

https://www.cms.gov/ - CMS Office of the Actuary, "Medicaid: A Brief Summary," in Brief Summaries of Medicare & Medicaid:

https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/MedicareProgramRatesStats/SummaryMedicareMedicaid.html - The federal Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission (MACPAC) publishes data and policy analysis and makes recommendations to Congress, the HHS Secretary, and states:

https://www.macpac.gov/ - MACPAC, Medicaid 101:

https://www.macpac.gov/medicaid-101/ - CMS, "Medicaid":

https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/index.html - MACPAC's "MACStats" compiles key national and state statistics from a variety of sources:

https://www.macpac.gov/macstats/ - CMS Fast Facts has national statistics on beneficiaries, expenditures, and services:

https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/CMS-Fast-Facts/index.html

Each state operates its own Medicaid programs within federal guidelines.

- Links to information on each state's Medicaid program:

https://www.medicaid.gov/state-overviews/index.html - Links to each state's Medicaid website and contact information; scroll to "2. Through your state Medicaid agency":

https://www.healthcare.gov/medicaid-chip/