Introduction

The U.S. Election Assistance Commission (EAC) is an independent federal agency charged with helping improve the administration of federal elections. It was established by the Help America Vote Act of 2002 (HAVA; P.L. 107-252; 116 Stat. 1666; 52 U.S.C. §§20901-21145) as part of Congress's response to administrative issues with the 2000 elections.1

The EAC—and the legislation that created it—marked a shift in the federal approach to election administration. Congress had set requirements for the conduct of elections before HAVA,2 but HAVA was the first federal election administration legislation also to back its requirements with substantial federal support.3 In addition to setting new types of requirements, it provided federal funding to help states meet those requirements and facilitate other improvements to election administration and created a dedicated federal agency—the EAC—to manage election administration funding and collect and share election administration information.4

There was broad support in Congress during the HAVA debate for the idea of providing some assistance along these lines. Both at the time and since, however, opinions have differed about exactly what kind of assistance to provide and for how long. Members have disagreed about whether the EAC should be temporary or permanent, for example, and about what—if any—regulatory authority it should have.

Changes in the election administration landscape and in Congress have brought different aspects of the debate to the forefront at various times. The 112th Congress saw the start of legislative efforts in the House to limit or eliminate the EAC, for example, while the agency's participation in the federal response to attempted foreign interference in the 2016 elections has been cited as new grounds to extend or expand it.5

This report provides an introduction to the EAC in the context of such developments. It starts with an overview of the EAC's duties, structure, and operational funding, and then summarizes the history of the EAC and legislative activity related to the agency. The report closes with some considerations that may be of interest to Congress as it conducts oversight of the EAC and weighs whether or how to take legislative action on either the agency or election administration more broadly.

|

EAC at a Glance Mission: "The U.S. Election Assistance Commission helps election officials improve the administration of elections and helps Americans participate in the voting process."6 Enabling Legislation: Help America Vote Act of 2002 (HAVA; P.L. 107-252; 116 Stat. 1666) Commission: Four members recommended by majority and minority congressional leadership and appointed by the President subject to the advice and consent of the Senate Advisory Bodies: Board of Advisors: 35 members representing a range of election administration stakeholders, including state and local officials, federal agencies, science and technology experts, and voters Standards Board: 110 members, with one state official and one local official from each of the 50 states, the District of Columbia, American Samoa, Guam, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands7 Technical Guidelines Development Committee: 15 members representing a range of election administration stakeholders, including state and local officials, individuals with disabilities, and science and technology experts Personnel (FY2019 Level): 31 full-time equivalent staff8 Appropriations for Salaries and Expenses (FY2019): $9.2 million, including $1.25 million for transfer to the National Institute of Standards and Technology9 Primary Oversight Committees: House Committee on House Administration and Senate Committee on Rules and Administration Appropriations Subcommittees: Financial Services and General Government |

Notes on Terminology

HAVA defines "states" as the 50 states, the District of Columbia, American Samoa, Guam, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands.10 This report takes a similar approach. Except where context makes clear that another meaning is intended, such as in references to "the 50 states," "state" is intended to include U.S. territories and the District of Columbia.

"Election Assistance Commission" and "EAC" are used by some to refer to the four-member commission that is part of the agency. To avoid confusion, this report reserves those terms for the agency as a whole and uses "commission" for the four-member commission.

Overview of the EAC

The EAC was created by HAVA, Congress's primary legislative response to problems with the administration of the 2000 elections. Issues with the vote count in Florida delayed the results of the 2000 presidential race for weeks.11 Subsequent investigations revealed widespread problems with states' conduct of elections. They also generated recommendations about how to prevent similar problems in the future, including via more expansive federal partnerships with states and localities.12

Exactly what those partnerships should look like was a matter of debate. There was broad agreement that they should involve some federal assistance to states and localities. Proposals from Members on both sides of the aisle and in both chambers of Congress included federal funding for improvements to election administration and federal guidance on voting system standards, for example.13

Members disagreed, however, about other features of the partnerships. These disagreements were rooted in part in competing concerns. Some Members were concerned that certain types of federal involvement would shift the balance of election administration authority from states and localities, which have traditionally had primary responsibility for administering elections, to the federal government.14 Others worried that states and localities would not—or could not—make necessary changes to their election systems without federal intervention.15

Disagreements about the federal government's role in election administration played out in at least two discussions that were relevant to the EAC: (1) whether new federal election administration responsibilities should be assumed by extant federal entities like the Federal Election Commission's (FEC's) Office of Election Administration (OEA) or an entirely new agency; and (2) whether the new responsibilities should be focused solely on supporting states and localities or should also include more expansive authority to compel states and localities to act.16

The EAC, like HAVA as a whole, was a compromise.17 It was a new agency, but its role was envisioned primarily as a support role. As one of the primary architects of HAVA, Representative Robert Ney, noted in the markup of the 2001 version of the bill,

[T]he name that we did choose, by the way, for this Commission is not an accident. The purpose of this Commission is to assist State and local governments with their election administration problems, basically taking the attitude we are the government, we are here to help. Its purpose is not to dictate solutions or hand down bureaucratic mandates.18

The following subsections provide an overview of the agency that emerged as a compromise from HAVA. They describe the EAC's duties, structure, and operational funding.

Duties

Consistent with the positioning of the EAC as a support agency, HAVA strictly limits the agency's power to compel action by states and localities. Responsibility for enforcing HAVA's national election administration requirements is assigned by the act to the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) and state-based administrative complaint procedures rather than to the EAC.19 Decisions about exactly how to comply with those requirements are reserved to the states.20 And EAC rulemaking is explicitly restricted to regulations for the voter registration reports and federal mail voter registration form required by the National Voter Registration Act of 1993 (NVRA; P.L. 103-31; 107 Stat. 77).21

Those limits do not mean the agency has no ability to influence state or local action. The EAC can trigger DOJ investigations of suspected violations of federal election law,22 for example, and revoke voting system certifications and testing lab accreditations.23 The agency can audit its grantees and specify how they should address issues identified by the audits.24 Its voting system testing and certification program can be binding on states that choose—as some states have—to make some or all of it mandatory under state law.25 Its voluntary guidance, while nonbinding, could be used by other agencies to inform HAVA enforcement.26

However, the EAC's duties are primarily envisioned by HAVA—and have primarily functioned—as support tasks. They fall into two general categories: (1) administration of funding and (2) collection and sharing of information.

Administration of Funding

The EAC is responsible for administering federal funding for improvements to election administration, including most of the grant and payment programs authorized by HAVA27 and an election data collection grant program that was authorized and funded by the FY2008 Consolidated Appropriations Act (P.L. 110-161).

Congress appropriated $380 million for payments to states under HAVA in FY2018 (P.L. 115-141), following reports of attempted foreign interference in the 2016 elections.28 Prior to those appropriations, funding was last provided for EAC-administered grants and payments in FY2010 (see Table 1 for details).29

|

Type of Funding |

Authorized Amount |

Appropriations Through FY2010a |

Appropriations Since FY2010 |

Selected U.S.C. Citations |

|

Payments to statesb for general improvements to the administration of federal elections |

$325.0 million |

$650.0 millionc |

$380.0 milliond |

52 U.S.C. §§20901, 20903-20906 |

|

Payments to states to replace lever or punch card voting systems |

$325.0 million |

— |

52 U.S.C. §§20902, 20903-20906 |

|

|

Payments to states to meet national election administration requirements (requirements payments)e |

FY2003: $1.4 billion FY2004: $1.0 billion FY2005: $600.0 million FY2010 and subsequent fiscal years: Such sums as may be necessaryf |

$2.6 billion |

— |

52 U.S.C. §§21001-21008 |

|

Grants for voting technology research |

FY2003: $20.0 million |

$8.0 million |

— |

52 U.S.C. §§21041-21043 |

|

Grants for voting technology pilot programs |

FY2003: $10.0 million |

$3.0 milliong |

— |

52 U.S.C. §§21051-21053 |

|

Funding for the National Student and Parent Mock Election Program |

FY2003: $200,000 Subsequent six fiscal years: Such sums as may be necessary |

$1.2 millionh |

— |

52 U.S.C. §§21071-21072 |

|

Funding for the Help America Vote Foundation |

FY2003: $5.0 million Subsequent fiscal years: Such sums as may be necessary |

$2.3 million |

— |

36 U.S.C. §§90101-90112 |

|

Funding for the Help America Vote College Program |

FY2003: $5.0 million Subsequent fiscal years: Such sums as may be necessary |

$4.7 millioni |

— |

52 U.S.C. §§21121-21123 |

|

Grants for election data collection pilot programs |

$10.0 million |

$10.0 millionh |

— |

52 U.S.C. §20981 note |

Source: CRS, based on analysis of the U.S. Code and relevant appropriations measures.

Notes: Figures are rounded and do not include rescissions or sequestration reductions. Appropriations figures include amounts specified in appropriations measures and accompanying explanatory statements.

a. The General Services Administration (GSA) handled some HAVA payments before the EAC had been set up, and the relevant appropriations included provisions for GSA's administrative expenses. Responsibility for administering the payments that were handled by GSA was subsequently transferred to the EAC.

b. HAVA defines "states" as the 50 states, the District of Columbia, American Samoa, Guam, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands.

c. The FY2003 appropriations bill included $650 million for the payments in the first two rows of this table without specifying a distribution of funds between them. The FY2003 bill also provided a one-time $15 million payment to reimburse states that had acquired optical scan or electronic voting machines prior to the November 2000 elections.

d. The explanatory statement accompanying the FY2018 appropriations bill indicated that this funding was intended to be used for enhancing election technology and improving election security. The amount appropriated in the FY2018 bill—$380 million—appears to be approximately equal to the difference between the $3 billion HAVA authorized for requirements payments and the amount Congress had appropriated for requirements payments through FY2018. HAVA sets conditions on requirements payments that do not apply to payments for general improvements to the administration of federal elections. For more on those conditions, see CRS Report RS20898, The Help America Vote Act and Election Administration: Overview and Selected Issues for the 2016 Election, by Arthur L. Burris and Eric A. Fischer.

e. HAVA required states that did not meet certain deadlines to return some of the funding they received for replacing lever and punch card voting systems. The act directed the EAC to use such returned funds for requirements payments.

f. Under HAVA, funding authorized for requirements payments for FY2010 and subsequent years may be used only to meet requirements added to the Uniformed and Overseas Citizens Absentee Voting Act of 1986 (UOCAVA; P.L. 99-410; 100 Stat. 924) by the Military and Overseas Voter Empowerment Act of 2009 (MOVE Act; P.L. 111-84; 123 Stat. 2190).

g. The FY2009 and FY2010 appropriations bills provided $1 million and $2 million, respectively, for a pilot program for grants to states and localities to conduct pre-election logic and accuracy testing and post-election verification of voting systems.

h. The explanatory statement accompanying the FY2008 appropriations bill designated $112,500 for administrative costs related to the mock election program and the election data collection pilot program.

i. The explanatory statement accompanying the FY2006 appropriations bill encouraged the EAC to spend an additional $250,000 on this program.

The EAC's administrative responsibilities typically extend past the fiscal year for which funding is appropriated. Much of the funding it administers has been provided as multiyear or no-year funds,30 and it performs ongoing funding maintenance tasks, such as providing technical assistance to funding recipients and issuing advisory opinions about proposed uses of funds.31 Through its Office of Inspector General (OIG), the EAC also audits grantees to confirm that they are meeting funding conditions, such as matching-fund and maintenance-of-effort requirements, and using funds as intended.32

Collection and Sharing of Information

HAVA folded the FEC's OEA into the EAC, transferring its staff, duties, and funding to the new agency.33 The OEA had performed a clearinghouse function at the FEC.34 That function was first established by the Federal Election Campaign Act of 1971 (P.L. 92-225; 86 Stat. 3) at the General Accounting Office (now called the Government Accountability Office [GAO]),35 as a source of election administration research and a forum for sharing election administration information.36 The function was transferred to the FEC when that agency was created in 1975 (P.L. 93-443; 88 Stat. 1263).37

The mandate expanded at the FEC to include creating and updating voluntary federal standards for voting systems and, following the enactment of the NVRA in 1993, producing a biennial voter registration report and developing and maintaining a federal mail voter registration form.38

These information collection and sharing functions have carried over to—and undergone further expansion at—the EAC. The following subsections describe the EAC's information collection and sharing duties.

Research and Coordination

Like its clearinghouse predecessors at GAO and the FEC, the EAC conducts election administration research and provides opportunities for election administration stakeholders to share their experience and expertise.39

Some of the work the EAC does as part of its research function is mandated specifically. The Election and Voting Survey (EAVS) it produces after each regular federal general election, for example, includes an NVRA-mandated voter registration report40 and reporting on military and overseas voting that is required by UOCAVA.41 The EAC was also directed by HAVA to conduct studies of military and overseas voting; voting system usability and accessibility; HAVA's voter identification requirement; use of Social Security information for voter verification; use of the internet in electoral processes; and postage-free absentee voting.42

The EAC also has considerable latitude to conduct other election administration research.43 It has issued a number of reports under this authority, including studies of rural versus urban election administration, alternative voting methods, and voter fraud and intimidation. The EAC has also released products that are specifically geared toward practitioners, such as a series of Quick Start Guides for election managers.44

The EAC facilitates information exchanges among election administration stakeholders in multiple ways, from publishing state and local best practices and requests for proposals to convening meetings and hosting roundtables and summits.45 One particularly high-profile example of the EAC's coordination work is its participation in the federal response to reports of attempted foreign interference in the 2016 elections. For more on that work, see the "The Agency's Role in Federal Election Security Efforts" section of this report.

Voting System Guidelines, Testing, and Certification

The FEC adopted the first voluntary federal voting system standards (VSS) in 1990 and updated them in 2002.46 The National Association of State Election Directors (NASED), a professional organization for state election directors, established a program to accredit labs to test voting systems to the VSS and certify systems as meeting the standards.47 When the EAC was created, it inherited enhanced versions of the FEC's and NASED's voting system guidelines, testing, and certification responsibilities.

The VSS were replaced at the EAC by Voluntary Voting System Guidelines (VVSG), which were called "guidelines" to distinguish them from the mandatory voting systems standards included among HAVA's national election administration requirements.48 One of the EAC's advisory bodies, the Technical Guidelines Development Committee (TGDC), is charged with drafting the VVSG.49 The draft guidelines are made available to the public, the agency's executive director, and the EAC's other two advisory bodies, the Board of Advisors and the Standards Board, for review and comment before they are submitted to the commissioners for a vote on adoption.50

The commissioners are also responsible for accrediting laboratories to test voting systems to the VVSG and revoking lab accreditations; certifying, decertifying, and recertifying systems as meeting the VVSG; and issuing advisories to help voting system manufacturers and testing labs interpret the VVSG. The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), which provides the TGDC with technical support on request and whose Director chairs the TGDC, is charged with monitoring voting system testing labs and making recommendations to the commission about lab accreditations and accreditation revocations.51

The VVSG were first adopted in 2005 and updated in 2015. The 2005 version updated and expanded the 2002 VSS to account for technological advances and to increase security and accessibility requirements.52 The 2015 iteration aimed to update outdated portions of the 2005 VVSG and increase the guidelines' testability.53

As of May 2019, the EAC was working on a second update (VVSG 2.0).54 Unlike previous versions of the VVSG, which were presented as device-specific recommendations, VVSG 2.0 separates higher-level principles and guidelines from technical details. The main document, which was released for public comment on February 28, 2019, sets out function-based principles, such as auditability, and guidelines, such as capacity to support efficient audits and resilience against intentional tampering. Supplementary documents are expected to provide the technical specifications required to help voting system manufacturers to implement—and voting system testing labs to test whether systems meet—the higher-level principles and guidelines.55

States are not required by federal law to adhere to the VVSG,56 but some have made the guidelines mandatory under their own state laws.57 States may also adopt other parts of the federal voting system testing and certification program. For example, they may choose to require voting systems to be tested by a federally accredited lab.58

Voluntary Guidance

HAVA set new national election administration requirements—such as certain standards for voting systems and requirements to offer provisional voting, post sample ballots at the polls on Election Day, and create and maintain a computerized statewide voter registration list59—and charged the EAC with adopting voluntary guidance about how to meet them.60

This voluntary guidance is intended to offer specifics about how to implement HAVA's general mandates. The EAC's guidance on statewide voter registration lists, for example, indicates that either a "top-down" system, in which a centrally located voter registration database is connected to local terminals, or a "bottom-up" system, in which information from locally hosted databases is used to update a central list, is acceptable under the law.61

As indicated by the name, this guidance is voluntary; states and localities can choose whether or not to adopt it.62 As noted above, however, the voluntary guidance the EAC issues could be used by other agencies to inform HAVA enforcement.

Structure

The EAC includes a four-member commission, a professional staff led by an executive director and general counsel, an OIG, and three advisory bodies: the Board of Advisors, the Standards Board, and the TGDC. Its primary oversight committees are the House Committee on House Administration and the Senate Committee on Rules and Administration.63 The components of the EAC are described in more detail in the subsections below.

The structure of the EAC was informed by at least three objectives:

- State and Local Partnership. The EAC's advisory bodies play a central role in the agency's functioning, and state and local officials or the professional associations that represent them serve on or appoint members to all three bodies.64

- Expert Input. The advisory bodies also feature a wide range of experience and expertise. In addition to state and local officials, members include representatives of voters, scientific and technical specialists, and disability access experts, among others.65

- Bipartisanship. The commission and two of the advisory bodies are designed to be politically balanced, and the commission cannot take certain actions without a three-vote majority of its members.

The agency's structure has also had implications for its functioning. For example, the three-vote quorum requirement for commission action has led at times to delays and inactivity. For more on such implications, see the "Debate About the Permanence of the Agency" section of this report.

|

Relationship of the EAC to Other Federal Entities Prior to the creation of the Election Assistance Commission (EAC), the Federal Election Commission (FEC) housed the main federal entity dedicated to election administration as a whole: the Office of Election Administration (OEA). The EAC inherited OEA's duties, funding, and staff from the FEC. The EAC and FEC both work on election-related issues, and there are parallels between the structures of their similarly even-numbered and bipartisan commissions. However, the two agencies have different mandates and authorities—the FEC is a regulatory agency that focuses on campaign finance while the EAC is a nonregulatory agency that covers election administration—and they do not generally work together. The EAC does work closely with other parts of the federal government. Multiple federal agencies are represented on its advisory bodies, and one of them, the National Institute of Standards and Technology, also contributes to some of the EAC's research, grant-making, and voting system testing and certification functions. The EAC provides election administration expertise to federal agencies directly and via reports and congressional testimony; collaborates with federal entities on research; and coordinates with federal agencies, state and local officials, and other election administration stakeholders. For example, following the designation of election systems as critical infrastructure in 2017, the EAC assisted the U.S. Department of Homeland Security with setting up the new Election Infrastructure Subsector.66 The EAC also has or has had relationships with other agencies that have had statutory obligations under the Help America Vote Act of 2002 (HAVA; P.L. 107-252; 116 Stat. 1666), including the General Services Administration, the Government Accountability Office, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, and the U.S. Department of Justice. For more on federal involvement in election administration, see CRS Report R45302, Federal Role in U.S. Campaigns and Elections: An Overview, by R. Sam Garrett. |

Commission

The commission is designed to have four members, each of whom is required to have elections experience or expertise and no more than two of whom may be affiliated with the same political party. Candidates for the commission are recommended by the majority or minority leadership of the House or Senate and appointed by the President subject to the advice and consent of the Senate.67

Commissioners are appointed to four-year terms on staggered two-year cycles.68 They may be reappointed to up to one additional term and may continue to serve on "holdover" status after their terms expire, pending appointment of a successor. Two commissioners representing different political parties are chosen by the commission membership each year to serve one-year terms as chair and vice chair.69

Certain actions by the commission require a three-vote majority of its members.70 According to an organizational management document adopted by the commission in February 2015, the commission is responsible for setting EAC policy.71 Among the actions that require a policymaking quorum of the EAC's commissioners are adopting voluntary guidance and the VVSG, appointing an executive director or general counsel, and promulgating regulations for the NVRA-mandated voter registration reports and federal mail voter registration form.72

Professional Staff

The EAC has two statutory officers—an executive director and a general counsel—who are appointed by the commission. Both serve four-year terms and are eligible for reappointment.73

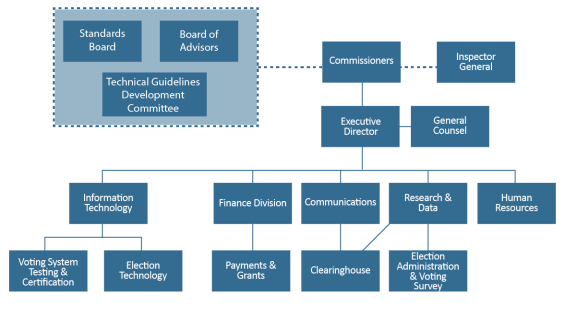

HAVA grants the executive director the authority to hire other professional staff (see Figure 1 for an organizational chart of the agency as of 2019).74 As a matter of policy, the executive director is also responsible for the day-to-day operations of the agency, including preparing policy recommendations for consideration by the commissioners, implementing adopted policies, and handling administrative affairs.75

|

|

Source: U.S. Election Assistance Commission, Fiscal Year 2020 Congressional Budget Justification, March 18, 2019, p, 10, at https://www.eac.gov/assets/1/6/EACFY2020BudgetJustification.pdf. |

The size of the EAC's staff has varied, from the four commissioners and handful of OEA transfers in FY2004 to 50 full-time equivalent staff (FTEs) in FY2010 and around 30 FTEs since FY2015.76 The number of FTEs the agency could maintain was capped at 22 in FY2005 and 23 in FY2006.77 The cap was lifted in FY2007 and, as of May 2019, had not been reinstated.78

Advisory Bodies

HAVA created three advisory bodies for the EAC: the Board of Advisors, the Standards Board, and the TGDC. The three bodies—whose members represent a variety of agencies, associations, organizations, and interests—play important roles in the agency's functioning. The following subsections describe their structures and responsibilities.

The Board of Advisors and the Standards Board

The EAC's Board of Advisors and its Standards Board review voluntary guidance and the VVSG before they are presented to the commissioners for a vote on adoption.79 In the event of a vacancy for executive director of the EAC, each of the boards is directed by HAVA to appoint a search committee for the position, and the commission is required to consider the candidates the search committees recommend.80 The commission is also directed to consult with the two boards on research efforts, program goals, and long-term planning; and the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) must consult with the boards on its monitoring and review of voting system testing labs.81

The Board of Advisors was initially assigned 37 members, but its membership dropped to 35 with the 2016 merger of two of the organizations responsible for appointing its members.82 Sixteen members of the board are appointed by organizations that represent state and local officials,83 and seven represent federal entities.84 Four members are science and technology professionals, who are each appointed by the majority or minority leadership of the House or Senate. The remaining eight are voter representatives, two of whom are appointed by each of the chairs and ranking members of the EAC's two primary oversight committees. The overall membership of the board is intended to be bipartisan and geographically representative.85

The Standards Board has 110 members. They include two representatives of each of the U.S. jurisdictions that are eligible for HAVA's formula-based payments: the 50 states, the District of Columbia, American Samoa, Guam, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands. Each pair of representatives consists of one state election official and one local election official who are not affiliated with the same political party.86

The Standards Board chooses nine of its members to serve two-year terms on its Executive Board. Executive Board members may serve no more than three consecutive terms, and no more than five Executive Board members may be either state officials, local officials, or members of the same political party.87

Technical Guidelines Development Committee

The 15-member TGDC is charged with helping the executive director of the EAC develop and maintain the VVSG. The Director of NIST serves as the chair of the committee and, in consultation with the commission, appoints its other 14 members. Appointees to the TGDC must include an equal number of members of the Board of Advisors, Standards Board, and Architectural and Transportation Barriers Compliance Board (Access Board); one representative of each of the American National Standards Institute (ANSI) and the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE); two NASED representatives who are chosen by the organization and neither share a political party nor serve on the Board of Advisors or Standards Board; and other individuals with voting system-related scientific or technical expertise.88

Office of Inspector General

The EAC is required to have an OIG under HAVA and the Inspector General Act of 1978, as amended (P.L. 95-452; 92 Stat. 1101).89 As noted in the "Administration of Funding" section of this report, the EAC's OIG oversees audits of the use of HAVA funding and refers issues identified in audits to EAC management for resolution and, if necessary, corrective action.90 In one instance, for example, the OIG determined that a HAVA grantee could not document its grant costs, and the EAC put the organization on a payment plan to return the funds.91 In another case, some of a state's spending was found to be impermissible and some was found to be inadequately documented. The state was directed to repay the former funding to the U.S. Treasury and the latter to its HAVA state election fund.92

The OIG also oversees internal audits and investigations of the EAC. This work includes regular audits of the EAC's finances and compliance with federal laws, such as the Federal Information Security Management Act of 2002 (P.L. 107-347; 116 Stat. 2899), and reports on management challenges facing the agency. It also includes special audits and investigations in response to complaints about fraud, waste, mismanagement, or abuse at the EAC, such as a 2008 investigation of allegations of political bias in the agency's preparation of a voter fraud and intimidation report and a 2010 investigation of complaints about its work environment.93

Operational Funding

The EAC has received operational funding for salaries and expenses, including for its OIG, in addition to the funding it has received for the grants and payments it administers and for transfers to NIST for HAVA-related activities like monitoring voting system testing labs. EAC appropriations have been under the jurisdiction of the Financial Services and General Government (FSGG) Subcommittees of the House and Senate Appropriations Committees since those subcommittees were created in 2007.94

HAVA explicitly authorized up to $10 million in operational funding for the EAC in each of FY2003, FY2004, and FY2005.95 Congress appropriated significantly less than the authorized ceiling in the first two fiscal years: $2 million in FY2003 (P.L. 108-7) and $1.2 million, plus approximately $500,000 transferred from the OEA, in FY2004 (P.L. 108-7; P.L. 108-199).96 The House Appropriations Committee also recommended significant cuts to the President's budget request for the agency from FY2012 through FY2018, although the enacted bills hewed more closely to presidential and Senate proposals. For more on those cases, see the "Setting up the Agency" section of this report and Table 2, respectively.

Congress appropriated $10.8 million for EAC salaries and expenses in the final year for which operational funding was explicitly authorized for the agency, FY2005 (P.L. 108-447).97 Although the explicit authorization of appropriations for EAC operations only ran through FY2005, the agency has continued to receive operational funding in subsequent years pursuant to its enabling legislation (see Table 2 for details).

Table 2. Proposed and Enacted Funding for EAC Operations from FY2006 to FY2019 (nominal $, in millions)

Figures for the House and Senate reflect chamber-passed, committee-reported, or other proposed levels, as indicated

|

Fiscal Year |

06 |

07 |

08 |

09 |

10 |

11 |

12 |

13 |

14 |

15 |

16 |

17 |

18 |

19 |

|

Enacted |

11.4 |

11.3 |

12.3 |

12.9 |

13.4 |

13.1 |

8.8 |

8.8 |

8.1 |

8.1 |

8.1 |

8.2 |

8.6 |

8.0 |

|

President |

14.8 |

12.0 |

12.2 |

12.7 |

13.3 |

13.6 |

10.5 |

8.8 |

8.3 |

8.1 |

8.1 |

8.3 |

7.7 |

7.7 |

|

Housea |

13.1 |

12.0 |

12.2 |

12.9 |

13.4 |

12.7 |

5.2 |

4.4 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

4.8 |

4.9 |

5.5 |

8.6b |

|

Senatea |

9.9 |

12.1 |

12.2 |

12.7 |

13.3 |

13.6 |

11.5 |

8.8 |

8.3 |

8.1 |

8.1 |

8.1 |

7.7 |

7.7 |

Source: CRS, based on data from the President's budget requests and appropriations bills, drafts, and reports.

Notes: Figures are from appropriations for the EAC's Salaries and Expenses account, including funds designated for the OIG. They are rounded and do not reflect rescissions, sequestration reductions, or funds designated for NIST, mock election grants, or the Help America Vote College Program.

a. Figures for the House and Senate indicate chamber-specific action: bold for a chamber-passed bill and regular text for a measure that did not pass the chamber. The figures in regular text are from committee-reported measures, with the exception of one case in which the measure was not reported out of subcommittee and another case in which it was not reported out of committee. The Senate figures for FY2015 and FY2018 are from the subcommittee bill and the committee chairman's draft, respectively.

b. This figure reflects the level in House-passed bill H.R. 6147. The House subsequently passed other bills that would have provided other levels of funding for the EAC.

Some Members have proposed explicitly reauthorizing appropriations for EAC operations, although none of the proposals had been enacted as of May 2019. For more on such proposals, see the "Proposals That Engage the Existing Role of the EAC" section of this report.

History of the EAC

It took some time for the EAC to become operational. HAVA called for members to be appointed to the agency's commission within 120 days of the act's enactment (on October 29, 2002), but the first four commissioners did not take office for more than a year.98 Without commissioners, the agency drew limited appropriations, and the lack of commissioners and funding led to inactivity and missed deadlines.

After nearly a decade of agency operations, the 112th Congress saw the start of efforts to limit or eliminate the EAC, as some Members of Congress questioned whether there was still a need for the agency. More recently—following reports of attempted foreign interference in the 2016 elections—proponents of the EAC have cited the agency's participation in federal election security efforts as new grounds to preserve it.99

This section traces the history of the EAC from its origins in the wake of the 2000 elections to its position after the 2016 elections.

Setting up the Agency

HAVA called for members to be appointed to the commission by February 26, 2003, but the first four commissioners did not take office until December 13, 2003.100

The act also explicitly authorized up to $10 million in funding for EAC operations for each of FY2003, FY2004, and FY2005.101 With no commissioners in place for the first of those fiscal years or the start of the second, Congress appropriated significantly less than that amount in FY2003 and FY2004 (P.L. 108-7; P.L. 108-199).

In a 2004 oversight hearing on the EAC, some Members of Congress expressed concern that the limited early funding and delays in establishing the EAC had affected the agency's ability to perform its duties.102 One Member referred, for example, to missed deadlines for adopting voluntary guidance.103 As set out in HAVA, the deadlines for the EAC to adopt voluntary guidance for meeting the act's requirements preceded the deadlines for states to start meeting them.104 In theory, that would have given states the chance to review the agency's guidance before they finalized action on the requirements.105 In practice, the commissioners took office nearly a month-and-a-half after the first guidance was due and less than three weeks before states were supposed to have started meeting requirements.106

Some of the deadlines for conducting statutorily mandated research had also passed before the commissioners were sworn in, and some commissioners testified that the early issues had caused them to limit the scope of their ambitions for other projects.107 "We are unable to do anything more than … really recite anecdotal things that we have heard as opposed to giving research-based guidance to States on how to implement" certain election measures, then-Commissioner Ray Martinez said about the commission's ongoing guidance work, for example. He added, "That is a critical point. We just don't have the means at this point to do anything other than how we are going about it, which I think is a very responsible and the best possible way that we can, but it is within the context of some very severely limited funds."108

Debate About the Permanence of the Agency

Some aspects of HAVA, such as the provision for reappointment of EAC commissioners to a second four-year term and the absence of a sunset provision for the agency, are consistent with a vision of the EAC as a continuing agency.109 Others, such as explicitly authorizing only three years of operational funding, suggest something more temporary.110 That has left room for debate about how long-lasting the EAC should be.

Some have viewed its proper role as permanent. At various points in the HAVA debate, for example, Members of the Senate characterized the agency as permanent.111 Other Members of Congress have highlighted benefits of ongoing EAC responsibilities like updating the VVSG, conducting the EAVS, and providing technical and other assistance to the states. They have argued that the tasks the EAC performs are essential and could not be carried out as effectively—or much more cost-effectively—by other agencies.112

Other Members have seen the agency as temporary. As of the beginning of the 112th Congress, the EAC had distributed much of the funding it was authorized by HAVA to administer and completed a number of the studies HAVA directed it to conduct. The National Association of Secretaries of State had recently renewed a resolution—first adopted in 2005 and subsequently to be approved again in 2015—that called for the agency's elimination.113 The EAC's inspector general reported ongoing issues with the agency's performance management, information security, work environment, records management, and overhead expenses.114

Such factors were cited by some as evidence that the agency had outlived its usefulness.115 Bills were introduced to terminate the EAC, and the House Appropriations Committee recommended cutting or eliminating its operational funding. For more on those activities, see the "Proposals to Terminate the EAC" section of this report and Table 2, respectively.

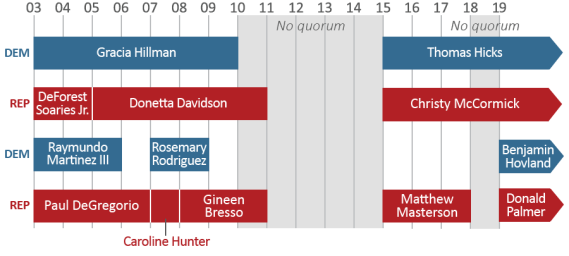

The Senate also stopped confirming—and some congressional leaders stopped recommending116—nominees to the EAC. The commission lost the numbers required for a policymaking quorum in December 2010 and both of its remaining members in December 2011 (see Figure 2 for details).117 The Senate, some of whose Members cited opposition to the ongoing existence of the agency rather than to individual nominees, did not confirm any new commissioners until December 2014.118

Without the numbers for a policymaking quorum, the commission could not take official action. One notable consequence was that it could not update the VVSG.119 The creation of the EAC was, in part, a response to the FEC's handling of the VSS. The committee report on legislation containing a precursor to the VVSG provisions of HAVA, for example, cited the FEC's failure to keep the VSS up to date.120 The lack of numbers for a quorum between December 2011 and the swearing-in of the newly confirmed commissioners in January 2015, however, left an almost 10-year gap between the EAC's initial adoption of the VVSG in 2005 and its first update in 2015.121

|

|

Source: CRS, based on data from the EAC and Congress.gov. |

The Agency's Role in Federal Election Security Efforts

The U.S. Intelligence Community reported in 2016 that foreign entities had attempted to interfere with that year's elections.122 The U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) responded in January 2017 by designating election systems as critical infrastructure,123 and Congress responded in March 2018 by appropriating $380 million for payments to states that, it indicated in an accompanying explanatory statement, it intended to be used for enhancing election technology and improving election security (see Table 1 for details).124

The EAC has participated in both responses. First, it was charged with administering the new payments to states (P.L. 115-141). Second, it helped set up—and, in some cases, serves as a member of—the special channels for sharing threat information and facilitating sector and subsector coordination that came with the critical infrastructure designation. Those channels include the Election Infrastructure Subsector's Government Coordinating Council and Executive Committee, Sector Coordinating Council, and Elections Infrastructure Information Sharing and Analysis Center.125

The EAC has also focused on election security in some of its other work. It has provided information technology management trainings for election officials, for example, and produced election security and critical infrastructure resources for voters.126

Supporters of a permanent role for the EAC have pointed to its participation in the federal government's election security efforts as a new reason to keep the agency.127 Other Members have also indicated that they see a longer-term role for the agency in light of the 2016 elections. For example, the House Appropriations Committee proposed increasing the EAC's operational funding above the President's budget request in FY2019 after seven years of recommending substantial cuts (see Table 2 for details).128

Legislative Activity on the EAC

The EAC has continued to be a subject of legislative activity since its creation by HAVA. It has been part of the appropriations process, receiving operational funding each fiscal year. For more on appropriations activity on the EAC, see the "Operational Funding" section of this report.

It has also featured in a range of authorizing legislation. Some post-HAVA authorization bills have tapped into the existing role of the agency, while others have proposed changes to that role. There have also been proposals that focused less on the nature of the role the EAC performs than on how it performs that role.

Proposals That Engage the Existing Role of the EAC

The EAC has traditionally been responsible for managing certain election administration-related funding, adopting guidance for meeting some national election administration requirements, serving as a federal source of election administration expertise, conducting election administration research, and helping connect election administration stakeholders with one another. Members looking for a federal agency to perform such tasks—to administer new grants to states to conduct risk-limiting audits, for example, or to set standards for electronic poll books—have often turned to the EAC in their legislative proposals.129 Members have also proposed explicitly reauthorizing appropriations for EAC operations either permanently or for a set number of years.

Table 3 presents selected examples of such bills.

|

Short Title |

Number |

Congress |

Latest Status |

Summary of Selected Provisions |

|

For the People Act of 2019 |

116th |

Passed House |

Would establish a National Commission to Protect United States Democratic Institutions, and direct the chair of the EAC to appoint one of its members |

|

|

Election Security Act |

115th |

Introduced |

Would have directed the EAC to make grants to states to replace voting systems, improve voting system security, and conduct risk-limiting audits |

|

|

Voter Registration Modernization Act |

114th |

Introduced |

Would have established national voter registration requirements, and directed the EAC to make payments to states to help meet them |

|

|

Voter Confidence and Increased Accessibility Act of 2014 |

113th |

Introduced |

Would have directed the EAC to develop best practices for documenting voting system chains of custody |

|

|

Federal Election Integrity Act of 2012 |

112th |

Introduced |

Would have directed states to provide voter ID cards at no charge to individuals who attest they cannot afford a fee, and directed the EAC to make payments to states to help provide the ID cards |

|

|

Voting Opportunity and Technology Enhancement Rights Act of 2009 |

111th |

Introduced |

Would have permanently reauthorized appropriations for operational funding for the EAC |

|

|

E-Poll Book Improvement Act of 2007 |

110th |

Introduced |

Would have directed the EAC to adopt voluntary guidance for electronic poll books and to include electronic poll books in federal testing and certification |

Source: CRS, based on data from Congress.gov.

Notes: The provisions summarized in this table are intended as examples of the types of proposals that have been offered. They do not include all proposals in all bills in this category or even, in some cases, all such proposals in the bill in which they appear.

Proposals to Change the Role of the EAC

The long-standing disagreements about the federal role in election administration that played out in the HAVA debate and in discussions about filling seats on the commission have also played out in post-HAVA legislative proposals. There have been proposals both to expand the EAC's authority and to eliminate the agency entirely. There have also been proposals to eliminate or substantially reduce the agency's funding. For more on proposed funding cuts, see the "Operational Funding" and "Debate About the Permanence of the Agency" sections of this report.

Proposals to Terminate the EAC

Some post-HAVA legislation has proposed eliminating the EAC. By the beginning of the 112th Congress, almost a decade had passed since HAVA was enacted. As noted in the "Debate About the Permanence of the Agency" section of this report, the EAC was nearing the end of some of the bigger projects it had been assigned by HAVA. And other agencies, such as NIST, were already playing a central role in ongoing EAC responsibilities like the federal voting system testing and certification program. There was a sense among some Members that there was no longer a need for a separate agency to fill the role the EAC had been filling. Combined with concerns about how the agency was being managed, this prompted calls to terminate it. Bills to disband the EAC and transfer duties to other agencies were introduced in each Congress from the 112th to the 115th.

Proposals to Expand the EAC's Authority

Other bills have taken the opposite tack, proposing new authority for the EAC. One such approach has been to revisit the limit on EAC rulemaking, proposing lifting it in certain cases—such as to permit the agency to promulgate regulations for a proposed new federal write-in absentee ballot—or striking it entirely. Another approach has been to propose giving the agency new powers to direct state or local action, such as imposing penalties for noncompliance with certain national election administration requirements or designating types of evidence that state and local officials may not use as grounds for removing individuals from the voter rolls.

Table 4 presents selected examples of proposals to terminate the EAC or to expand its authority.

|

Short Title |

Number |

Congress |

Latest Status |

Summary of Selected Provisions |

|

Voter Empowerment Act of 2019 |

116th |

Introduced |

Would permit the EAC to designate evidence that may not be used as the basis for removing voters from the rolls |

|

|

Election Assistance Commission Termination Act |

115th |

Introduced |

Would have terminated the EAC |

|

|

Election Integrity Act of 2016 |

114th |

Introduced |

Would have struck the limit on EAC rulemaking |

|

|

Election Support Consolidation and Efficiency Act |

112th |

Failed House |

Would have terminated the EAC |

|

|

Voting Opportunity and Technology Enhancement Rights Act of 2009 |

111th |

Introduced |

Would have directed the EAC to establish a federal write-in absentee ballot and lifted the limit on EAC rulemaking as applied to the new absentee ballot |

|

|

Valuing Our Trust in Elections Act |

109th |

Introduced |

Would have permitted the EAC to impose penalties for noncompliance with the act's requirements on states that receive funding under the act |

|

|

Voter Confidence and Increased Accessibility Act of 2003 |

108th |

Introduced |

Would have directed the EAC to conduct unannounced manual recounts of election results |

Source: CRS, based on data from Congress.gov.

Notes: The provisions summarized in this table are intended as examples of the types of proposals that have been offered. They do not include all proposals in all bills in this category or even, in some cases, all such proposals in the bill in which they appear.

Proposals to Change the Way the EAC Works

Some post-HAVA legislation on the EAC has focused less on what the agency does and more on how it does it. Bills have been introduced that propose structural changes to the agency, such as adding members to its advisory bodies or creating new advisory boards or task forces, and procedural changes, such as adjusting the payment process for voting system testing, changing how the EAC submits its budget requests, and exempting the agency from certain federal requirements.

Such proposals aim to address perceived weaknesses in the way the agency operates. Some proposals may be responses to perceived inefficiencies in current processes, such as delays caused by the commission's quorum requirement or the public comment requirement of the Paperwork Reduction Act of 1980 (P.L. 96-511; 94 Stat. 2812), or to a perceived need for new kinds of experience or expertise at the agency. Other proposals may aim to prevent possible conflicts of interest, such as by eliminating direct payments from vendors to voting system testing labs, or to give Congress more insight into the agency's resource needs, such as by requiring it to submit budget requests to Congress at the same time as it sends them to the President or the Office of Management and Budget.130

Table 5 presents selected examples of these kinds of structural and procedural proposals.

|

Short Title |

Number |

Congress |

Latest Status |

Summary of Selected Provisions |

|

For the People Act of 2019 |

116th |

Passed House |

Would add the Secretary of DHS to the EAC's Board of Advisors and a DHS representative to the TGDC |

|

|

Voting Innovation Prize Act of 2018 |

115th |

Introduced |

Would have directed the EAC to establish a prize competition for voting technology innovation and permitted the EAC to promulgate relevant regulations and carry out the act without a quorum |

|

|

Voter Empowerment Act of 2013 |

113th |

Introduced |

Would have directed the EAC to establish an escrow account for payments to voting system testing labs and a schedule of testing fees for vendors |

|

|

Voter Advocate and Democracy Index Act of 2007 |

110th |

Introduced |

Would have created an Office of the Voter Advocate and Board of Advisors to help the EAC develop and administer a Democracy Index |

|

|

Bipartisan Electronic Voting Reform Act of 2008 |

110th |

Introduced |

Would have added representatives of the voting system manufacturing industry and accessibility and usability sector to the TGDC |

|

|

Secure America's Vote Act of 2005 |

109th |

Introduced |

Would have directed the EAC to submit its budget estimates and requests to Congress at the same time as it sent them to the President or the Office of Management and Budget |

Source: CRS, based on data from Congress.gov.

Notes: The provisions summarized in this table are intended as examples of the types of proposals that have been offered. They do not include all proposals in all bills in this category or even, in some cases, all such proposals in the bill in which they appear.

Potential Considerations for Congress

Congress has the authority to conduct oversight of the EAC and to legislate on both the EAC in particular and election administration more generally.131 In addition to issues raised by previous legislative proposals, such as whether to terminate the agency, the following issues may be of interest to Members as they consider whether or how to undertake such activities or whether to maintain the status quo:

Providing for New Expertise. The EAC was structured to ensure input from a range of election administration stakeholders, from voters to technical specialists to accessibility experts.132 However, new developments, such as new election security threats, might call for experience or expertise not currently represented at the agency. If Congress seeks to assure the EAC access to such experience or expertise, how might it do so? Some possible options include directing the EAC to consult with specialist organizations or agencies, funding specialized professional staff or creating specialized departments within the agency, adding members to one or more of the advisory bodies, and establishing new advisory bodies or task forces. Are there reasons to prefer some of these options over others? For example, the EAC's advisory bodies play a particularly central role in the functioning of the agency. Are there reasons to want certain stakeholders to have—or not to have—such direct access to EAC actions and decisionmaking?133

Assigning (and Reassigning) Responsibilities. The EAC is the only federal agency dedicated to election administration as a whole.134 As such, it is often taken to be the obvious choice to assume federal election administration responsibilities. As noted above, however, some Members have suggested that some of the duties currently in the EAC's portfolio might be better performed by other agencies or in other ways.135 Are there election administration-related issues about which parts of the federal government other than the EAC might have relevant expertise? For example, the EAC has traditionally been the primary federal repository of election administration best practices, but DHS also provides resources related to election security.136 Questions might arise, with respect to certain elections-related duties, about which agency—or combination of agencies—is best positioned to perform them. More broadly, how might the EAC's and other agencies' comparative advantages guide assignment of new federal election administration responsibilities or reassignment of existing responsibilities?

Assessing and Meeting Resource Needs. The EAC has been described variously as both overfunded and underfunded.137 Developments like the emergence of new election security threats have prompted calls for additional resources for agency operations and for distribution to states via the EAC.138 How do current levels of funding match up to the agency's—and its grantees'—resource needs? Are there tools, such as concurrent budget submission or research into appropriate funding levels for HAVA payments, that might help Congress better assess those needs?139 Are there resources other than funding, such as security clearances for commissioners or professional staff, that the EAC needs and does not currently have?

Considering the Role of the Quorum Requirement. The quorum requirement for official action by the commission has led at times to delays and inactivity, such as deferred updates to the VVSG. Does Congress seek to consider ways to reduce the likelihood or frequency of such delays? If so, would it prefer an approach that eliminated the need for a quorum in certain cases, such as by exempting certain actions from the quorum requirement,140 or one that reduced the likelihood of the commission being without a quorum? Options for the latter approach might include structural changes to the commission, such as adding or removing a seat, or procedural changes to the way commissioners are seated, such as revising the roles of the President and congressional leadership in the candidate selection process.

Scheduling EAC Action. HAVA envisioned that the EAC would adopt voluntary guidance about how to meet the act's national election administration requirements before the states actually had to meet them. The idea was to give states the opportunity to review the federal guidance before finalizing their actions on the requirements.141 Subsequent legislative proposals have similarly called for new national election administration requirements and EAC guidance about how to meet them.142 How might deadlines be set in such proposals to give the EAC time to research and adopt meaningful guidance and the states time to make best use of it? Are there additional conditions that might need to be set—or support that might need to be provided—to ensure that the deadlines can be met?