Introduction

The Old-Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance (OASDI) program provides monthly benefits to retired or disabled workers and their family members and to the family members of deceased workers. The OASDI program operates as a pay-as-you-go program in which revenues (collected from payroll taxes and taxation of benefits) are paid out as monthly benefits. These monthly benefits constitute a substantial portion of income for a large segment of recipients.

The payroll tax and the taxation of monthly benefits are major contributors to the OASDI program's revenues. For many years, the program's revenues exceeded its costs (i.e., benefit payments), resulting in annual surpluses. Annual surpluses are not needed to cover scheduled benefits, and the money is credited to the Old-Age and Survivors Insurance Trust Fund and the Disability Insurance Trust Fund, or trust funds. The OASDI Trust Funds are invested in nonmarketable U.S. government securities (government bonds), where they earn interest. This interest provides a third source of revenue to the OASDI program. The combined OASDI Trust Funds had approximately $2.9 trillion in assets at the beginning of 2018.1

The OASDI Trust Funds' Board of Trustees (the trustees) manages the trust funds according to requirements set forth in the Social Security Act. Under current law, the trust funds' assets may be invested only in U.S. government securities issued by the Secretary of the Treasury. In practice, the trust funds invest solely in special, nonmarketable U.S. Treasury securities. By investing only in nonmarketable U.S. Treasury securities, or special issues, the trustees have not intervened directly in the private economy. Investing in marketable securities would signify a departure from the norms that govern the current investment practice. Investing in equities—for example, by purchasing company stock in the open market—would demonstrate a similar departure from the trust funds' investment norms and would represent a government intervention into the private market. Some argue this expansion of investment options would be problematic because it dictates government ownership of, and possibly influence on, private companies. Although this event may never come to pass, the historically higher returns on equity investment may motivate policymakers to enact changes to the OASDI Trust Funds' investment options and practices.2

Current Policies and Practices3

Section 201(c) of the Social Security Act establishes the Board of Trustees of the OASDI Trust Funds and states that the Secretary of the Treasury shall be the managing trustee.4 Subsequent sections outline the main duties of the managing trustee and provide instructions for how to conduct the trust funds' investment activities. The directives include the following:

- 1. The managing trustee is to invest portions of the trust funds that are not required for current costs.5

- 2. The funds not necessary to meet current costs are to be invested only in interest-bearing securities issued by the Secretary of the Treasury.6 Upon purchasing a government security (i.e., exchanging tax revenues or earned interest for a government security), the surplus funds are deposited into the General Fund and the funds are available to the rest of the federal government to meet other spending needs, reduce taxes, or reduce publicly held debt. This transaction essentially results in excess revenues being loaned to the government.7

- 3. The U.S. Treasury will make these securities available to the managing trustee for the trust funds' investments.8 These issues are referred to as special issues or special obligations.

- a. The maturity of special issues is fixed with due regard for the needs of the trust funds.9

- b. The interest rate earned by special issues is equal to the average market yield on marketable, interest-bearing government securities due at least four years in the future.10

- 4. The managing trustee may redeem any of these special issues, at any time, at par (i.e., face value) plus accrued interest.11

The ability to redeem the special issues at any time for par value, thus ensuring they cannot lose value, makes them nonmarketable. Other U.S. government issuances, if sold prior to maturity, are redeemed at the prevailing market rate. Because these special issues can always be redeemed at par, their early redemption at any time does not negatively affect the trust funds' value.12

If it is determined to be in the public interest, the managing trustee may purchase non-special issues (e.g., marketable U.S. securities) at the original or market price.13 Doing so would imply that any redemption, if needed prior to the maturity date of such security, would return the market price and possibly result in losses to the trust funds' capital. The 1957-1959 Advisory Council on Social Security Financing acknowledged that the trust funds could invest in public (i.e., marketable) issues, but recommended amending the Social Security Act to allow investment in public issues only "when they will provide currently a yield equal to or greater than the yield that would be provided by the alternative of investing in special issues."14 Had this amendment been enacted into law, it would have mandated the preference for special issues.

The Social Security Act provides no direction on how the trust funds' investments should be redeemed. In practice, the trustees have adopted two administrative policies to address this gap. First, special issues are redeemed before maturity only when they are required to cover immediate costs. This policy prevents special issues with a low yield from being redeemed and then immediately reinvested at a higher rate. Second, special issues are redeemed in maturity-date order.15 This policy provides a reliable order of redemption.

The Trust Funds' Investment Principles

Actuarial Note Number 142, published by the Social Security Administration's Office of the Chief Actuary (OCACT), outlines the OASDI Trust Funds' investment principles. The note acknowledges that the legislative history of the Social Security Act provides only limited guidance, and the rest can be inferred from the administrative policies adopted over the duration of the trust funds' existence.16

Principle 1: Nonintervention in the Private Economy

The principle of nonintervention has long been recognized as important in the consideration of the trust funds' finances. The 1957-1959 Advisory Council on Social Security Financing stated the following in its final report:

The Council recommends that investment of the trust funds should, as in the past, be restricted to obligations [issues] of the United States Government. Departure from this principle would put trust fund operations into direct involvement in the operation of the private economy or the affairs of State and local governments. Investment in private business corporations could have unfortunate consequences for the social security system—both financial and political—and would constitute an unnecessary interference with our free enterprise economy. Similarly, investment in the securities of State and local governments would unnecessarily involve the trust funds in affairs which are entirely apart from the social security system.17

The principle of nonintervention is reinforced by the creation and use of the special issue securities as the OASDI Trust Funds' primary investment mechanism.18 The purchase or sale of large quantities of marketable government securities in the open market by the OASDI Trust Funds could cause market disruptions and appear as interference in the open market operations of the Federal Reserve.19

Principle 2: Security

Section 201(d) of the Social Security Act explicitly states the OASDI Trust Funds may only be invested in interest-bearing securities issued by or guaranteed by the U.S. government.20 These securities are backed by the full faith and credit of the government, offering them a high measure of protection.21 Furthermore, to the degree that the trust funds remain invested solely in special obligations (special issues), they are well protected from any loss to capital, earning a risk-free return.22

Principle 3: Neutrality

With respect to operating neutrally, Actuarial Note Number 142 states the following:

Trust fund investment policies have, for the most part, followed a principle of neutrality, in the sense that they have generally been intended neither to advantage or disadvantage the trust funds (the lenders) with respect to other Federal accounts (the borrowers). The underlying concept is that when the trust funds invest assets by lending to the general fund of the Treasury, these transactions should produce investment results similar to those that might be obtained by a prudent, private sector investor in Federal securities. If the general fund could not borrow from the trust funds, it would have to meet its borrowing needs by selling additional securities to just such private investors.23

The practice of neutrality is required, in part, by law in determining the interest rates for the special issues (see "Current Policies and Practices"). It is also encouraged by two administrative policies adopted by the trust funds: (1) only redeeming special issues before maturity when they are needed to meet program costs and (2) ensuring the maturities of special issues are evenly distributed among 1-year through 15-year durations. Note 142 concludes that "the administrative policy governing early redemption of special obligations [special issues], in combination with the policy of spreading maturities, is designed to compensate at least partially for, or neutralize, the advantage of no-risk liquidity."24

Principle 4: Minimal Management of Investment

The parameters for the trust funds' investment set forth in the Social Security Act and the administrative policies adopted over time render active or day-to-day management of the trust funds' investments unnecessary.25 The types of possible investment vehicles are limited by law and by common practices. These practices have also eliminated discretion for when and why securities should be redeemed. Note 142 also explains that adhering to the principles of security and neutrality necessitates following the principle of minimal management, as active management (e.g., profit maximizing) would violate the first two principles.26

Performance and Criticism of the Trust Funds

The Trust Funds' Performance

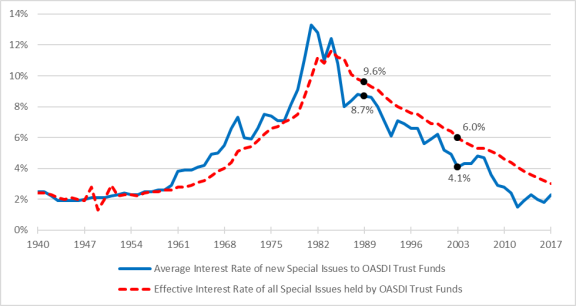

Figure 1 displays the returns earned by the assets in the trust funds over the period 1940 to 2017. The average interest rate is the average of the monthly interest rates on new special issues acquired by the trust funds during that year. In 2003, for instance, the average interest rate for the special issues acquired by the OASDI Trust Funds was 4.1%. The effective interest rate is the interest earned during the calendar year on all of the securities held by the trust funds divided by the average amount of securities held by the trust funds during the year. Since 1985, the effective interest rate has been higher than the average interest rate due to securities in the trust funds acquired in earlier years when interest rates were much higher. For example, Figure 1 shows that in 2003 the effective interest earned by all special issues held in the trust funds was 6.0%.

This relationship between the average interest rate and the effective interest rate is a consequence of the trust funds' special issues being evenly spread over maturity periods ranging from 1 year to 15 years. In an environment of falling interest rates, the trust funds' investment practices result in one-fifteenth of the trust funds' assets coming due each year and being invested at a lower interest rate.27 For instance, a portion of the special issues acquired in 1989 was invested for a duration of 15 years, thus maturing in 2003. Those special issues returned an average rate of 8.7% and would have then been invested in assets that were expected to earn an average rate of 4.1% (i.e., the average interest rate for new special issues in 2003). Similarly, a portion of special issues acquired in 1994 for a duration of 10 years earned an average rate of 7.1%; these special issues would also have been invested to earn an average of 4.1% (i.e., the average interest rate for new special issues in 2003). It must be reiterated, however, that this duration structure has afforded the trust funds a higher effective rate than the average rate, earned in an essentially risk-free manner.

|

Figure 1. Effective and Average Annual Interest Rates for the Combined OASDI Trust Funds, 1940-2017 |

|

|

Source: Graph prepared by the Congressional Research Service (CRS) from data provided by the Social Security Administration (SSA), Office of the Chief Actuary, at https://www.ssa.gov/oact/progdata/annualinterestrates.html. Note: For comparison of the Trust Funds' effective interest rate and that of equity investments, see "Equity Investment and Risk." |

Criticism of the Trust Funds

Criticism of the OASDI Trust Funds' current investment practices stems from the program's long-term solvency issues. The program is facing a funding shortfall due largely to demographic factors, and restoring long-term solvency would require a payroll tax increase or reduction in benefits. Critics argue that if the trust funds had earned a better return in the past, they would be in a better long-term financial position. The 1994-1996 Advisory Council on Social Security stated the following in its final report:

Historically, returns on equities have exceeded those on Government bonds (where all Social Security funds are now invested). If this equity premium persists, it would be possible to maintain Social Security benefits for all income groups of workers, greatly improving the money's worth for younger workers without incurring the risks that could accompany individual investment.… As a matter of financial theory, the diversification achieved by investing in both stocks and government bonds should also reduce portfolio risk for the OASDI Trust Fund.28

Starting in 1998, the Social Security Advisory Board (SSAB) replaced the advisory councils. Since then, the SSAB has released numerous reports that affirm the prior advisory council's findings. In reports from 2005 and 2010, the SSAB noted that the increased rate of return offered by equities would eliminate a large portion of the projected funding shortfall and reduce the need for tax increases or benefit reductions.29

Because of declining interest rates and the trust funds' duration and reinvestment practice, a portion of the trust funds' holdings was continually being invested in securities that earned less than they did in the past (see Figure 1). This trend is expected to continue. Although the SSA's OCACT projects interest rates to increase over the next 10 years, much of the maturing holdings would still be reinvested at a lower rate.30

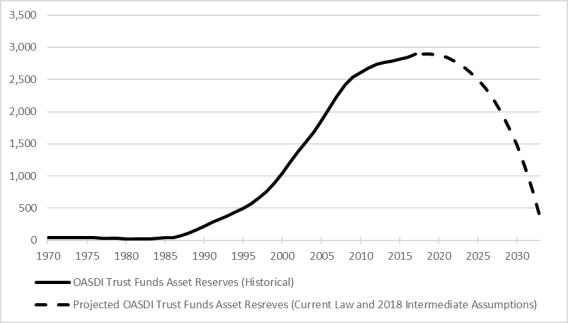

Figure 2 shows the value of the asset reserves in the OASDI Trust Funds at the end of each calendar year from 1957 to 2034 based on historical data and projections. The figure shows the value of assets growing from 1983 through 2017. The Social Security Amendments of 1983 established a number of provisions, including increasing the full retirement age, adding new federal workers into the OASDI program, and taxing Social Security benefits, which had a positive effect on the OASDI Trust Funds.31 From 1983 to 2017, OASDI program revenues exceeded program cost, resulting in annual surpluses. However, during the 1983-2017 period of sustained annual surpluses, the trust funds experienced falling interest rates (see Figure 1).

Figure 2 depicts that at the end of 2017, the trust funds are also projected to be at peak value. For 2018, the trustees project that program costs will exceed program revenues. The assets previously invested in the trust funds will be drawn down to augment annual program revenues and fulfill annual scheduled payments. The trustees also project that under current law costs will exceed revenues for the entirety of their 75-year projection period. Under the projection, the OASDI program will be able to draw upon the trust funds' assets to fulfill scheduled payments until 2034, the date at which the trustees project assets will be depleted.

|

Figure 2. Historical and Projected OASDI Trust Funds Asset Reserves, 1957-2034 (in billions of nominal dollars) |

|

|

Sources: Figure prepared by CRS from data provided in the 2018 Annual Report, Table VI.G8, 220 and the Supplemental Single-Year tables, at https://www.ssa.gov/oact/tr/2018/lr6g8.html. Note: The combined OASDI Trust Funds become depleted in 2034 under the intermediate assumptions. |

Alternative Investments and Possible Issues

The 1994-1996 Advisory Council on Social Security identified the demographic implications of the aging baby boom generation—those born from 1946 through 1964—and the associated effects on the trust funds as an issue.32 As a result, the council's final report recommended investing a portion of the trust funds in equities to help alleviate pressure on the OASDI program's long-term actuarial balance. Other alternatives included investments in private (e.g., corporate) bonds, or in social and economic activities, such as housing construction.33

The primary argument for the trust funds to invest in private equity is that historical returns on equity have been greater than returns on government bonds.34 Some critics of this approach are concerned that by investing in private companies and gaining some control over their activities, the federal government would be intervening in the market, resulting in what some have described as "socialism by the backdoor method."35 The advisory council reasoned as follows:

Another practical disadvantage would be the need for a far-reaching and deep-searching investment policy that would permit the trust funds to obtain an adequate rate of interest with reasonable security of principal. Under such a policy, the Federal Government would, in effect, be setting itself up as a rating organization, because the investment procedures would naturally have to be open to full public view. If no preference were shown for different types of securities, but rather investments were made widely and indiscriminately, there would be a substantial risk of diminution of investment income, or even loss of principal.36

Alternatively, it could be argued that if the trust funds invested passively into an index fund, the managing trustee or Board of Trustees could forgo voting rights.37 Although this may help to solve, or at least alleviate, the issue of government control over private companies, it may introduce new risks. The value of shares in companies included in the chosen index would receive a steady stream of support from routine and unconditional government purchase of their shares. Investing trust fund assets in index funds—for example, by investing in an index of the largest 500 companies—may effectively create an atmosphere where these companies, by the value of their market capitalization, are chosen as the "winners" via the trust funds' purchases.38 The benefits of being among the winners could provide incentives for companies near the cutoff in market capitalization to adopt accounting methods not generally accepted as good practice. Deceptive accounting methods could be used to inflate stock prices and market capitalization for the purpose of becoming a winner wherein the company would benefit from consistent purchase of its stock by the trust funds.39

Investing the trust funds' assets in private equities or bonds could also introduce instability to the financial markets. Whereas Figure 2 shows that the trust funds' values on a year-to-year basis are smooth, the trust funds' balance fluctuates greatly throughout the year.40 The need to redeem the trust funds' assets throughout the year, combined with the trust funds' ebbs and flows, presents conditions that have the potential to disrupt private markets.41 Large sales of private stocks and bonds needed to smooth fluctuations in the trust funds' value may create a liquidity crisis where irregular price movements prohibit sales and purchases at market prices; a lack of liquidity is also a reason critics cite for not investing in social projects such as housing or hospitals.42

Lastly, for the trust funds to purchase equities, some portion of the trust funds' existing special issues would need to be redeemed to provide the necessary capital. Research presented in the following sections suggests a phase-in of equity purchases worth 2.67 percentage points of the trust funds' value per year. Phasing in the purchase of equities in 2018 at 2.67 percentage points would have required the redemption of approximately $77 billion worth of special issues.43 In other words, the federal government would have needed to find $77 billion to redeem these special issues so the cash could be invested in equities. Providing that capital for the new equity investments would require a corresponding increase in publicly held debt, a corresponding increase in tax revenue, or a corresponding reduction in other government spending. Subsequent years would require similar redemptions as well.

Equity Investment and Risk

Investing the trust funds' assets in equities could introduce instability to the financial markets. Conversely, the trust funds would also be subject to the volatility already present in the markets. The higher average returns offered by equity investments are accompanied by higher risk. The degree of volatility, or risk, among investment vehicles is positively correlated to returns; that is, investments that can offer greater returns are accompanied by greater volatility. Likewise, investments that offer lower returns are accompanied by lower volatility. Investing in equities may improve the overall financial health of the trust funds, but it would likely be accompanied by higher volatility, which could pose challenges for a system dependent on dedicated sources of funding.

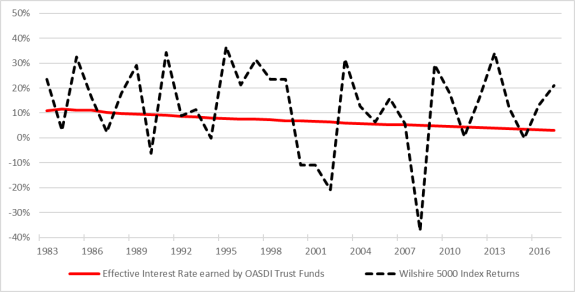

Figure 3 displays the effective interest rate earned by the special issues in the combined OASDI Trust Funds and the returns of the equity market as measured by the Wilshire 5000 Total Market Index, or Wilshire 5000. During the 1983-2017 period, the Wilshire 5000 returns outperformed the trust funds' effective interest rate in 21 of the 35 years. The average effective interest rate of special issues in the OASDI Trust Funds over this period was 5.8% versus an average return of 12.7% earned in the Wilshire 5000. At the same time, the equity returns demonstrated a higher degree of volatility.

|

Figure 3. Comparison of the OASDI Trust Funds' Effective Interest Rate and Wilshire 5000 Returns, 1983-2017 |

|

|

Sources: Graph prepared by CRS. Effective interest rate for the combined OASDI Trust Funds is provided by SSA' Office of the Chief Actuary, at https://www.ssa.gov/oact/progdata/annualinterestrates.html. Historical data for the Wilshire 5000 are provided by Wilshire Associates at https://www.wilshire.com/indexcalculator/#. |

Railroad Retirement Board and Alternative Investments

Many of the issues mentioned above are similar to the experiences of the Railroad Retirement Board, or RRB, an independent federal agency that administers benefits to railroad workers and their families. In 2001, Congress passed the Railroad Retirement Survivors' Improvement Act, which established the National Railroad Retirement Investment Trust (NRRIT).44 To ensure independence and limit political interference, the NRRIT is not a part of the federal government and is independent of the RRB.45

Congress aimed to increase RRB funding by realizing higher returns than would be possible from investing solely in government securities.46 As such, the act requires the NRRIT to invest a portion of the RRB's assets in non-U.S. government securities, such as private stocks and bonds. The NRRIT investment practices require a diversified portfolio to minimize risk and avoid disproportionate influence over a firm or industry. From the NRRIT's inception to the end of FY2016, the investment returns helped increase the value of assets held by the RRB. From FY2003 to FY2016, annual returns averaged 7.9%, compared with expected returns of 8%. These rates of return are higher than what would have been earned if the NRRIT invested solely in government securities (Figure 1); prior to the act's implementation, the NRRIT was invested in government securities in much the same manner as the OASDI Trust Funds.47 The overall size of assets held by the NRRIT is considerably smaller than the OASDI Trust Funds. For instance, at the end of FY2017, the market value of NRRIT-managed assets was $26.5 billion, whereas at the end of CY2017, the OASDI Trust Funds held $2,892 billion in assets.48 For a complete overview of the NRRIT, see CRS Report RS22782, Railroad Retirement Board: Trust Fund Investment Practices.

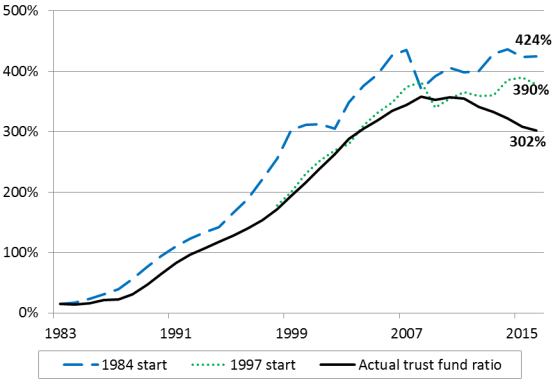

Alternative Investments and Review of Past Performance

With accurate and precise knowledge of the OASDI Trust Funds' cash flows from 1983 through 2016, it is possible to model the trust funds' performance had they participated in alternative investments. Research published by Burtless et al. at the Center for Retirement Research in 2017 sought to determine how the trust funds would have benefited if alternative investments began in 1984, after the Social Security Amendments of 1983 ushered in a 34-year period of annual surpluses, and in 1997, after the last Advisory Council on Social Security recommended trust fund investment in equity.49 This analysis compares how incorporating equity investments would have affected the OASDI Trust Funds ratio. The trust funds ratio is the measure of the trust funds' asset reserves at the beginning of the year divided by the projected total cost for the year. According to the trustees, a trust funds ratio above 100% throughout the short-range period (10 years) indicates a financially healthy program, whereas a ratio below 100% signals the program is in a financially inadequate position. The results are presented in Figure 4 below. The scenarios presented below assume that the amount of the trust funds' reserves invested in equities would increase by 2.67 percentage points per year until 40% of reserves were allocated in equities.50 That is, the trust funds' purchase of equities was phased in until equities represented 40% of total assets.

|

Figure 4. OASDI Trust Funds Ratio with Equity Investment by Starting Year, |

|

|

Source: Gary Burtless et al., What Are The Costs And Benefits Of Social Security Investing In Equities?, Center For Retirement Research at Boston College, Number 17-10, May 2017, p. 3, http://crr.bc.edu/briefs/what-are-the-costs-and-benefits-of-social-security-investing-in-equities/. Notes: Both scenarios assume the percentage of trust funds assets invested in equities would increase by 2.67 percentage points each year up to a maximum equity allocation of 40%. The Wilshire 5000 returns are used for historical performance of the equity market. |

This analysis yields several insights, the most pertinent of which may be that if the trust funds had invested in equities in the past, they would have higher levels of assets today than they currently do. Figure 4 shows that at the end of 2016, undertaking equity investments in 1983 would have left the trust funds with reserves enough to cover about an additional 1.2 years of program costs (424% less 302%); equity investing beginning in 1997 would have supplied the trust funds with assets to cover an additional 0.88 years of program costs (390% less 302%). In other words, the trust funds would still be facing long-term insolvency even with equity investment. A second item of note is that from 1983 to 2008, when the actual trust funds ratio peaked, the analysis shows that investing in equities would not have drastically improved the financial situation. The actual trust funds ratio was 358% in 2008, contrasted with a ratio of 371% if investment in equities began in 1984 and a ratio of 383% if investment began in 1997. By 2008, the current investment strategy resulted in a similar trust funds ratio, accomplished with less risk, with no intervention into the capital markets, and at minimal cost. A third observation is that despite several large downturns, most notably the 2008-2009 financial crisis, the trust funds would still stand in a better financial position today had equity investments been incorporated. Lastly, in each of these two alternative cases, the trust funds would have owned less than 10% of the total value of the stock market today.51 This result owes to the growth in aggregate equity value contrasted with the phased-in purchases of equity. Trust fund ownership at this level would perhaps assuage the concerns of critics wary of government intervention in the equity markets.52

Alternative Investments and Projections for Future Performance

Impact of Various Policy Options Without Revenue Increase

OCACT maintains relevant estimates on policy options that would affect the program's long-range solvency. The options for investing in equities presented in Table 1 vary by phase-in date, percentage of reserves that would be invested in equities, and assumed real rate of return. Policy options that incorporate equity investing can be assessed by examining their effects on the long-range actuarial balance.53 Table 1 shows that under current law, the long-range actuarial balance is -2.84% of taxable payroll, indicating that under intermediate assumptions provided in The 2018 Annual Report, an approximately 2.84-percentage-point increase in payroll tax rate (from current the 12.40% to 15.24%) or a comparable reduction in benefits would be needed to maintain program solvency throughout the projection period and result in a trust funds ratio of 100% at the end of the projection period.54

As shown in Table 1, none of the options that incorporate investing the trust funds in equities is projected to result in an appreciable change in the long-term solvency of the program. The best-performing option, G1, involves investing 40% of the OASDI Trust Funds into equities, phased in from 2019 to 2033, and it assumes a real rate of return of 6.2%. Although OCACT projects this option to improve the long-range actuarial balance by 0.51 percentage points, the trust funds' cash flow operations are still projected to result in depletion, albeit in 2035, one year later than expected under current law.

Table 1. Policy Options Without Revenue Increase That Incorporate Trust Funds' Investment In Marketable Securities

|

Summarized Estimates (percentage points of payroll tax) |

||||

|

Provision |

Description |

Long-Range Actuarial Balance |

Annual Balance in 75th Year |

Trust Funds Reserve Depletion |

|

Current Law |

-2.84 |

-4.32 |

2034 |

|

|

G1 |

Invest 40% of OASDI Trust Funds reserves in equities (phased in 2019-2033), assuming an ultimate 6.2% annual real rate of return on equities. |

-2.33a |

-4.36a |

2035 |

|

G2 |

Invest 40% of OASDI Trust Funds reserves in equities (phased in 2019-2033), assuming an ultimate 5.2% annual real rate of return on equities. |

-2.47a |

-4.36a |

2035 |

|

G3 |

Invest 40% of OASDI Trust Funds reserves in equities (phased in 2019-2033), assuming an ultimate 2.7% annual real rate of return on equities. Thus, the ultimate rate of return on equities is the same as that assumed for the Trust Funds' bonds. |

-2.84a |

-4.36a |

2034 |

|

G4 |

Invest 15% of OASDI Trust Funds reserves in equities (phased in 2019-2028), assuming an ultimate 6.2% annual real rate of return on equities. |

-2.63a |

4.36a |

2035 |

|

G5 |

Invest 15% of OASDI Trust Funds reserves in equities (phased in 2019-2028), assuming an ultimate 2.7% annual real rate of return on equities. Thus, the ultimate rate of return on equities is the same as that assumed for the trust funds' bonds. |

-2.84a |

-4.36a |

2034 |

|

G6 |

Invest 25% of OASDI Trust Funds reserves in equities (phased in 2021-2030), assuming an ultimate 6.2% annual real rate of return on equities. |

-2.52a |

-4.36a |

2035 |

|

G7 |

Invest 25% of OASDI Trust Funds reserves in equities (phased in 2021-2030), assuming an ultimate 2.7% annual real rate of return on equities. Thus, the ultimate rate of return on equities is the same as that assumed for the trust funds' bonds. |

-2.84a |

-4.36a |

2034 |

Sources: Table prepared by the Congressional Research Service (CRS) from data provided by the Social Security Administration (SSA), Office of the Chief Actuary, at https://www.ssa.gov/oact/solvency/provisions/investequities_summary.html. Estimates based on the intermediate assumptions of The 2018 Annual Report, at https://www.ssa.gov/OACT/TR/2018/tr2018.pdf.

a. A change in the investment of trust fund reserves to include some equities does not affect the scheduled cash flows, which is the difference between income excluding interest (i.e., revenues from payroll taxes and taxation of benefits) and cost (i.e., scheduled benefits). Therefore, although including some trust fund reserves in equities may improve the long-range actuarial position, because that improvement does not affect cash flows it cannot be interpreted directly as a reduction in the shortfall.

As shown in Figure 2, the combined OASDI Trust Funds value at the end of 2017 represents a peak value. As it becomes necessary to draw upon those assets to pay scheduled benefits, there will be less and less money that can be invested. Therefore, the projected drawdown of the trust funds makes any potential advantage of investing in equities less effective over time. Once the trust funds are depleted, the OASDI program's cost is projected to remain greater than revenues indefinitely. When the trust funds are depleted, any measure involving investment in equities would have no effect on solvency, as there would be no money to invest.

Impact of Various Policy Options with Revenue Increase

The Burtless et al. research that examined how the trust funds would have fared by including alternative investments from 1984 to 2016 also sought to determine how the trust funds would perform moving forward from 2017. Table 1 shows that policy options that do not include any increase to revenue do not result in an appreciable change to the current trajectory of the OASDI Trust Funds' insolvency. As such, the researchers' simulations first require that Congress passes legislation to "restore balance to the system."55 To restore balance to the system, the authors assume that payroll taxes are raised to eliminate the long-run funding shortfall—at the end of 2016 this was projected to require a 2.58-percentage-point increase in the payroll tax.56 After the balance is restored, there is no longer any long-term funding shortfall, as the actuarial deficit is brought to zero. If enacted in 2016, an increase in the payroll tax of 2.58 percentage points, on a stand-alone basis, would have resulted in the projected solvency being extended from 2034 to 2091.57

With balance now restored to the system, the authors present two scenarios. The first scenario is a continuation of current policy in which the trust funds remain solely invested in special issues. The second scenario presents projections in which the trust funds increase the amount of their reserves invested in equities by 2.67 percentage points per year until no more than 40% of the trust funds' assets are equities. This second scenario is similar to the simulated scenarios of past performance presented in "Alternative Investments and Review of Past Performance."

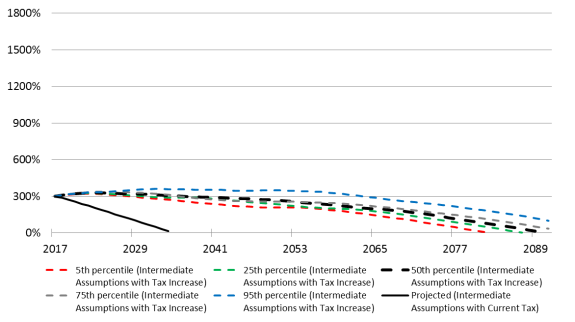

Once the OASDI program is brought back into balance (i.e., projected to be solvent throughout the 75-year projection period), Monte Carlo simulations are used to model the two scenarios.58 The results of continuing to invest only in special issues are presented below in Figure 5, which shows the range of outcomes for the trust funds ratios for simulated special issue returns grouped into percentiles based on the outcome of the final year in the simulation. For instance, the 95th percentile shows that the average of the top 5% of simulations resulted in a trust funds ratio of 100% in the final year, 2091. Conversely, the 5th percentile, those simulations in the bottom 5%, resulted in trust fund depletion in 2083, on average. For reference, the graph also shows the projected trust funds ratio from The 2018 Annual Report (solid black line), which does not include any increase in payroll tax or investment in equities.

The results of the simulations correspond with the Trustees' 2018 Annual Report. The simulations at the 50th percentile, the best guess estimate, project that program solvency would be extended to about 2090, assuming first a reduction in the actuarial deficit. The simulations at the 5th percentile resulted in maintaining short-range financial adequacy through 2071 and solvency through 2082.59 In essence, Figure 5 shows the improved adequacy of the trust funds' financial position from a tax increase but with no change to the current investment practices.

|

Figure 5. Projected OASDI Trust Funds Ratio Under Current Law and Simulated OASDI Trust Funds Ratios with a Tax Increase, 2017-2091 |

|

|

Sources: Gary Burtless, et al., What Are The Costs And Benefits Of Social Security Investing In Equities?, Center For Retirement Research at Boston College, Number 17-10, May 2017, p. 3, http://crr.bc.edu/briefs/what-are-the-costs-and-benefits-of-social-security-investing-in-equities/. Projected values for the trust funds ratios are from data provided in Table VI.B4 (intermediate assumptions), Supplemental Single-Year Tables Consistent with the 2018 Annual Report, at https://www.ssa.gov/oact/TR/2018/lr4b4.html. (The value for 2017 is historical data.) Notes: The percentiles are determined by the rank of outcomes in 2091. The paths follow the simulations along the 75-year horizon. Values that were below 0% were omitted by the CRS author. The projected trust funds ratio under the Trustees' intermediate assumption assumes current law, whereas all other projections assume the system is first brought into balance. |

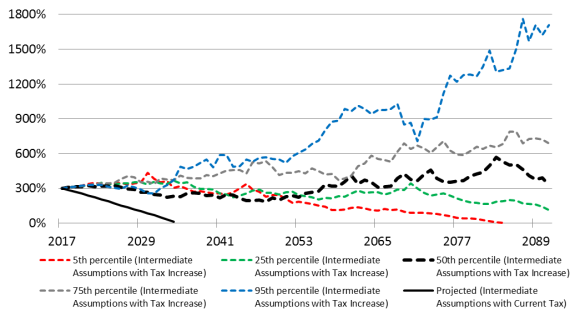

In contrast, a second scenario, shown in Figure 6, simulates how incorporating equity investment following the tax increase, wherein the trust funds hold a mixed portfolio of equity (at most 40%) and special issues (at least 60%), would alter the trust funds' performance.

The results in Figure 6 show the potential benefits from equity investing. In this scenario, the simulations at the 50th percentile, the best guess estimate, resulted in a mixed portfolio that is valued at 330% of the next year's projected costs (i.e., a trust funds ratio of 330%) at the end of the projection period. Comparing the 50th percentile outcomes under each scenario shows that incorporating equity investments could improve the trust funds' long-range financial position. The only instance in which the special issue-only practice performs similarly to the mixed portfolio is under the worst possible outcomes, those in the 5th percentile of each scenario. In these groups, the mixed portfolio fails the short-range adequacy test at an earlier date, 2069 versus 2071 for the special issue-only; however, it remains solvent for two years longer than the special issue-only, 2084 versus 2082.60 In almost all simulated scenarios, the inclusion of equities into the trust funds' investment practices improved their long-range financial position.61

|

Figure 6. Projected OASDI Trust Funds Ratio Under Current Law and Simulated OASDI Trust Funds Ratios with a Tax Increase (Investing in a Mixed Portfolio of 40% Equities and 60% Special Issues), 2017-2091 |

|

|

Sources: Gary Burtless, et al., What Are The Costs And Benefits Of Social Security Investing In Equities?, Center For Retirement Research at Boston College, Number 17-10, May 2017, p. 3, http://crr.bc.edu/briefs/what-are-the-costs-and-benefits-of-social-security-investing-in-equities/. Projected values for the trust funds ratios are from data provided in Table VI.B4 (intermediate assumptions), Supplemental Single-Year Tables Consistent with the 2018 Annual Report, at https://www.ssa.gov/oact/TR/2018/lr4b4.html. (The value for 2017 is historical data.) Notes: The percentiles are determined by the rank of outcomes in 2091. The paths follow the simulations along the 75-year horizon. Values that were below 0% were omitted by the CRS author. The projected trust funds ratio under the Trustees' intermediate assumption assumes current law, whereas all other projections assume the system is first brought into balance. The percentage of the trust funds' reserves invested in equities is phased in over the projected period, increasing 2.67 percentage points a year until equities comprised 40% of the portfolio. |

A Railroad Retirement Board Approach for Social Security?

The scenarios presented above appear suggest that after the long-term funding shortfall is eliminated, the inclusion of equity investing into the trust funds could improve the Social Security program's solvency. A change of this nature would represent a large departure from current policy.

Since 2002, the National Railroad Retirement Investment Trust (NRRIT) has incorporated equity purchases in its management of a portion of Railroad Retirement Board (RRB) assets.62 From FY2003 through FY2017, the NRRIT achieved annual rates of return after fees of 8.3%.63 From calendar years 2003 through 2017, the OASDI Trust Funds achieved an average effective return of 4.5%.64 Although this comparison in performance between the NRRIT and OASDI Trust Funds covers the 2008-2009 financial crisis, it is somewhat limited in overall duration. In addition, any comparison between the two programs must take into account the smaller size of the NRRIT.

The board of the NRRIT is composed of seven trustees who have expertise in financial management and pension plans. Three of the members are selected by labor unions and three by railroad management. These six members select the final trustee, and all trustees are limited to three-year terms. The trustees hire independent investment managers to invest the NRRIT assets, with no one manager controlling more than 10% of the assets.65

Whereas features such as a nonfederal entity of trustees seem easily replicable, other features of the NRRIT model may prove more difficult to copy. The pursuit of higher returns is accompanied by additional risk (see "Equity Investment and Risk"). To compensate for the additional risk, the NRRIT has developed safeguards to protect against periods of low returns.66 These safeguards include fund reserves of four to six years' worth of benefits (i.e., trust fund ratio of 400% to 600%) and automatic payroll tax adjustments on employees and employers.67

To acquire asset reserves of at least four years of annual program costs, thus maintaining a safeguard similar to the NRRIT's, the OASDI Trust Funds would require substantial revenue-increasing or benefit-reducing measures. For instance, as discussed in the previous section, for the OASDI Trust Funds to be brought into balance before the purchase of equities, an increase of 2.58 percentage points to the payroll tax is required. Even with the additional returns generated by equity investments under the best-case scenario presented in Figure 6 (i.e., simulated equity returns in the 95th percentile), a trust funds ratio of 400% is not attained until 2035.

Some features of the NRRIT model may prove more difficult for policymakers to accept. For instance, automatic payroll tax adjustments could prove hard to implement. About 93% of the work in the United States is covered by Social Security.68 Given this high coverage rate, some policymakers may object to automatic adjustments to a payroll tax that affects so many workers. In addition, an automatic increase of the payroll tax to maintain a specific trust funds ratio (e.g., 400%) would most likely occur during a period of low equity returns. Thus, such an increase could occur when workers and businesses were already subject to negative equity returns. However, a more sizeable trust funds ratio, such as 600%, could provide adequate contingency funds such that an automatic increase in the payroll tax would not be prompted. Periods with a high trust funds ratio and positive equity returns could prompt an automatic payroll tax decrease. Lastly, the amount of funds managed by the NRRIT versus those managed by the OASDI Trust Funds are different. At the end of FY2017, the NRRIT managed assets with a market value of $26.5 billion. At the end of CY2017, the OASDI Trust Funds managed assets worth $2,892 billion.

Because the NRRIT is an independent nongovernmental entity, it is not subject to the same oversight as federal agencies. Several times since its inception, the RRB Office of the Inspector General (OIG) has expressed concerns regarding the effectiveness of proper oversight of the NRRIT.69 Most specifically, the OIG noted that, under current policy, there are fewer safeguards protecting the NRRIT than for retirement investments of federal government and private-sector workers.70 Given the magnitude of the Social Security program and its importance for retired workers, a similar absence oversight may prove unacceptable to policymakers.

Conclusion

Under current law, and assuming the Board of Trustees' intermediate projections will unfold close to its assumptions, the long-range solvency of the OASDI Trust Funds is at risk. In addition, under current law, the trust funds' financial position would not be improved by the inclusion of alternative investments, namely equity investments. However, should Congress pass legislation to reduce the actuarial deficit, available research suggests that investing the trust funds' newly increased assets in equities could result in a higher trust funds ratio (i.e., greater solvency) than if the trust funds' assets were invested in only government bonds. Phasing in equity investments over a sufficient length of time could minimize adverse effects and result in the trust funds holding a relatively small position in the stock market. Although much smaller in scale, the practices of the RRB provide a framework and history for the use of equity investment in a trust fund (see CRS Report RS22782, Railroad Retirement Board: Trust Fund Investment Practices). This would, however, require putting aside current investment principles and methods that have guided investment practices. These practices have led the OASDI Trust Funds to be managed at a low cost with minimal risk and resulted in no direct intervention in the private equity markets.