Introduction

The U.S. energy pipeline network is integral to the nation's energy supply and provides vital links to other critical infrastructure, such as power plants, airports, and military bases. These pipelines are geographically widespread, running alternately through remote and densely populated regions—from Arctic Alaska to the Gulf of Mexico and nearly everywhere in between. Because these pipelines carry volatile, flammable, or toxic materials, they have the potential to injure the public, destroy property, and damage the environment. Although they are generally an efficient and comparatively safe means of transport, pipeline systems are nonetheless vulnerable to accidents, operational failure, and malicious attacks. A series of accidents in California, Pennsylvania, and Massachusetts, among other places, have demonstrated this vulnerability and have heightened congressional concern about U.S. pipeline safety. The Department of Energy's first Quadrennial Energy Review (QER), released in 2015, also highlighted pipeline safety as a growing concern for the nation's energy infrastructure.1

The federal pipeline safety program resides primarily within the Department of Transportation's (DOT's) Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA), although its inspection and enforcement activities rely heavily upon partnerships with the states. Together, the federal and state pipeline safety agencies administer a comprehensive set of regulatory authorities which has changed significantly over the last decade and continues to do so. The federal pipeline safety program is authorized through the fiscal year ending September 30, 2019, under the Protecting Our Infrastructure of Pipelines and Enhancing Safety Act of 2016 (PIPES Act; P.L. 114-183) signed by President Obama on June 22, 2016.

This report reviews the history of federal programs for pipeline safety, discusses significant safety concerns, and summarizes recent developments focusing on key policy issues. It discusses the roles of other federal agencies involved in pipeline safety and security, including their relationship with PHMSA. Although pipeline security is not mainly under PHMSA's jurisdiction, the report examines the agency's past role in pipeline security and its recent activities working on security-related issues with other agencies.

The U.S. Pipeline Network

The U.S. energy pipeline network is composed of approximately 3 million miles of pipeline transporting natural gas, oil, and hazardous liquids (Table 1). Of the nation's approximately half million miles of long-distance transmission pipeline, roughly 215,000 miles carry hazardous liquids—over two thirds of the nation's crude oil and refined petroleum products, along with other products.2 The U.S. natural gas pipeline network consists of around 300,000 miles of interstate and intrastate transmission. It also contains some 240,000 miles of field and gathering pipeline, which connect gas extraction wells to processing facilities. However, with 7% of gathering lines currently under federal regulation (discussed later in this report), the total mileage of U.S. gathering lines is not known more precisely. Few state agencies collect this information. The natural gas transmission pipelines feed around 2.2 million miles of regional pipelines in some 1,500 local distribution networks serving over 69 million customers.3 Natural gas pipelines also connect to 152 active liquefied natural gas (LNG) storage sites, as well as underground storage facilities, both of which can augment pipeline gas supplies during peak demand periods.4

|

Category |

Miles |

|

Hazardous Liquids |

215,628 |

|

Natural Gas Gathering (onshore) |

240,000 |

|

Natural Gas Transmission |

300,655 |

|

Natural Gas Distribution Mains and Service Lines |

2,223,209 |

|

TOTAL |

2,979,492 |

Sources: PHMSA, "Annual Report Mileage Summary Statistics," web tables, February 1, 2019, http://www.phmsa.dot.gov/portal/site/PHMSA/menuitem.7c371785a639f2e55cf2031050248a0c/?vgnextoid=3b6c03347e4d8210VgnVCM1000001ecb7898RCRD&vgnextchannel=3b6c03347e4d8210VgnVCM1000001ecb7898RCRD&vgnextfmt=print; and "Gathering Pipelines FAQs," web page, August 20, 2018, https://www.phmsa.dot.gov/faqs/gathering-pipelines-faqs.

Notes: Hazardous liquids primarily include crude oil, gasoline, jet fuel, diesel fuel, home heating oil, propane, and butane. Other hazardous liquids transported by pipeline include anhydrous ammonia, carbon dioxide, kerosene, liquefied ethylene, and some petrochemical feedstock.

Safety in the Pipeline Industry

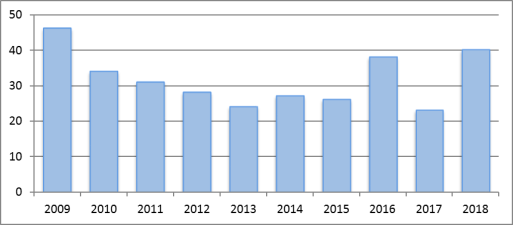

Uncontrolled pipeline releases can result from a variety of causes, including third-party excavation, corrosion, mechanical failure, control system failure, operator error, and malicious acts. Natural forces, such as floods and earthquakes, can also damage pipelines. Taken as a whole, releases from pipelines cause few annual injuries or fatalities compared to other product transportation modes.5 According to PHMSA statistics, there were, on average, 12 deaths and 66 injuries annually caused by 32 pipeline incidents in all U.S. pipeline systems from 2009 through 2018.6 After steady decline between 2009 and 2013, the average incident count increased and recently shows no clear trend (Figure 1). A total of 40 serious pipeline incidents was reported for 2018.

|

Figure 1. Pipeline Incidents Causing Injuries or Fatalities (Annual "Serious" Incidents) |

|

|

Source: PHMSA, "Pipeline Incident 20 Year Trends," online database, November 1, 2018, https://www.phmsa.dot.gov/data-and-statistics/pipeline/pipeline-incident-20-year-trends. Note: PHMSA defines "serious" incidents as those including a fatality or injury requiring inpatient hospitalization. |

Apart from injury to people, some accidents may cause environmental damage or other physical impacts, which may be significant, particularly in the case of oil spills or fires. PHMSA requires the reporting of such incidents involving

- $50,000 or more in total costs, measured in 1984 dollars,

- highly volatile liquid releases of 5 barrels or more or other liquid releases of 50 barrels or more, or

- liquid releases resulting in an unintentional fire or explosion.7

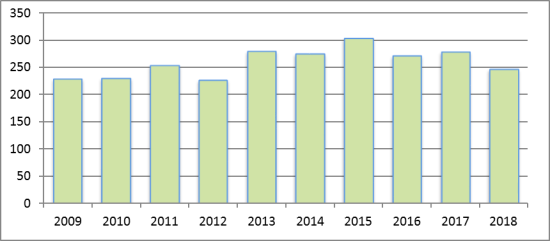

On average there were 260 such "significant" incidents (not involving injury or fatality) per year from 2009 through 2018. As with serious incidents, there is no clear trend for pipeline incidents affecting only the environment or property over the last five years (Figure 2). It should be noted that federally regulated pipeline mileage overall rose approximately 7% over this period; neither the annual statistics for injury nor environmental incidents are adjusted on a per-mile basis.8

|

Figure 2. Pipeline Incidents Causing Environmental or Property Damage (Annual "Significant" Incidents) |

|

|

Source: PHMSA, "Pipeline Incident 20 Year Trends," online database, November 1, 2018, https://www.phmsa.dot.gov/data-and-statistics/pipeline/pipeline-incident-20-year-trends. Note: Includes "significant" incidents, which involve $50,000 or more in total costs (in 1984 dollars), highly volatile liquid releases of 5 barrels or more or other liquid releases of 50 barrels or more, or liquid releases resulting in an unintentional fire or explosion. Excludes "serious" incidents causing a fatality or injury requiring inpatient hospitalization. |

Although pipeline releases have caused relatively few fatalities in absolute numbers, a single pipeline accident can be catastrophic in terms of public safety and environmental damage. Notable pipeline and pipeline-related incidents over the last decade include the following:

- 2010―A pipeline spill in Marshall, MI, released 19,500 barrels of crude oil into a tributary of the Kalamazoo River.

- 2010—An explosion caused by a natural gas pipeline in San Bruno, CA, killed 8 people, injured 60 others, and destroyed 37 homes.

- 2011―An explosion caused by a natural gas pipeline in Allentown, PA, killed 5 people, damaged 50 buildings, and caused 500 people to be evacuated.

- 2011―A pipeline spill near Laurel, MT, released an estimated 1,000 barrels of crude oil into the Yellowstone River.

- 2012—An explosion caused by a natural gas pipeline in Springfield, MA, injured 21 people and damaged over a dozen buildings.

- 2013—An oil pipeline spill in Mayflower, AK, spilled 5,000 barrels of crude oil in a residential community causing 22 homes to be evacuated.

- 2014—An explosion caused by a natural gas distribution pipeline in New York City killed 8 people, injured 50 others, and destroyed two 5-story buildings.

- 2015—A pipeline in Santa Barbara County, CA, spilled 3,400 barrels of crude oil, including 500 barrels reaching Refugio State Beach on the Pacific Ocean.

- 2015—The Aliso Canyon underground natural gas storage facility in Los Angeles County, CA, released 5.4 billion cubic feet of gas, causing the temporary relocation of over 2,000 households and two schools in Porter Ranch.

- 2016—An explosion caused by a natural gas distribution pipeline in Canton, OH, killed one person, injured 11 others, and damaged over 50 buildings.

- 2018—Explosions and fires caused by natural gas distribution pipelines in the Merrimack Valley, MA, killed one person, injured 21 others, damaged 131 structures, and required 30,000 residents to evacuate.

Such incidents have generated persistent scrutiny of pipeline regulation and have increased state and community activity related to pipeline safety.

Federal Agencies in Pipeline Safety

Three federal agencies play the most significant roles in the formulation, administration, and oversight of pipeline safety regulations in the United States. As stated above, PHMSA has the primary responsibility for the promulgation and enforcement of federal pipeline safety standards. The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) is not operationally involved in pipeline safety but examines safety issues under its siting authority for interstate natural gas pipelines. The National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) investigates transportation accidents—including pipeline accidents—and issues associated safety recommendations. These agency roles are discussed in the following sections.

Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration

The Natural Gas Pipeline Safety Act of 1968 (P.L. 90-481) and the Hazardous Liquid Pipeline Act of 1979 (P.L. 96-129) are two of the principal early acts establishing the federal role in pipeline safety. Under both statutes, the Transportation Secretary is given primary authority to regulate key aspects of interstate pipeline safety: design, construction, operation and maintenance, and spill response planning. Pipeline safety regulations are covered in Title 49 of the Code of Federal Regulations.9

PHMSA Organization and Funding

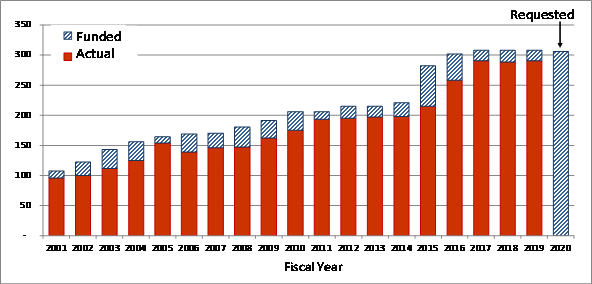

As of March 8, 2019, PHMSA employed 290 full-time equivalent (FTE) staff in its Office of Pipeline Safety (OPS)—including 145 regional inspectors—and in DOT offices outside of OPS that also support pipeline safety functions.10 Those staff include attorneys, data analysts, information technology specialists, and regulatory specialists required for certain enforcement actions, promulgating regulations, issuing pipeline safety grants, and issuing agreements for pipeline safety research and development.11

In addition to federal staff, PHMSA's enabling legislation allows the agency to delegate authority to intrastate pipeline safety offices, and allows state offices to act as "agents" administering interstate pipeline safety programs (excluding enforcement) for those sections of interstate pipelines within their boundaries.12 According to the DOT, "PHMSA leans heavily on state inspectors for the vast network of intrastate lines."13 A few states serve as agents for inspection of interstate pipelines as well. There were approximately 380 state pipeline safety inspectors in 2018.14

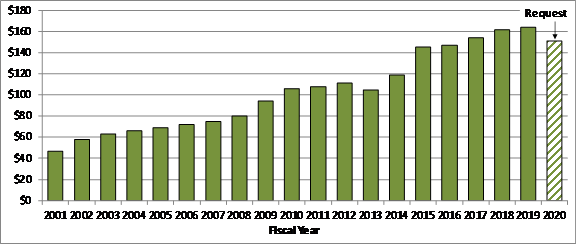

PHMSA's pipeline safety program is funded primarily by user fees assessed on a per-mile basis on each regulated pipeline operator.15 The agency's total annual budget authority has grown fairly steadily since 2001, with the largest increase in FY2015 (Figure 3). For FY2019, PHMSA's estimated budget authority is approximately $164 million—more than double the agency's budget authority in FY2008 (not adjusted for inflation). The Trump Administration's requested budget authority for PHMSA is approximately $151 million for FY2020, roughly 8% less than the FY2019 budget authority, with proposed reductions primarily in contract programs, research and development, and grants to states.16

PHMSA's Regulatory Activities

PHMSA uses a variety of strategies to promote compliance with its safety standards. The agency conducts programmatic inspections of management systems, procedures, and processes; conducts physical inspections of facilities and construction projects; investigates safety incidents; and maintains a dialogue with pipeline operators. The agency clarifies its regulatory expectations through published protocols and regulatory orders, guidance manuals, and public meetings. PHMSA relies upon a range of enforcement actions, including administrative actions such as corrective action orders (CAOs) and civil penalties, to ensure that operators correct safety violations and take measures to preclude future safety problems.

From 2014 through 2018, PHMSA initiated 943 enforcement actions against pipeline operators.17 Of these cases, 348 resulted in safety orders to operators. Civil penalties proposed by PHMSA for safety violations during this period totaled approximately $24.2 million.18 PHMSA also conducts accident investigations and system-wide reviews focusing on high-risk operational or procedural problems and areas of the pipeline near sensitive environmental areas, high-density populations, or navigable waters.

Since 1997, PHMSA has increasingly required industry's implementation of "integrity management" programs on pipeline segments near "high consequence areas." Integrity management provides for continual evaluation of pipeline condition; assessment of risks to the pipeline; inspection or testing; data analysis; and follow-up repair; as well as preventive or mitigative actions. High consequence areas (HCAs) include population centers, commercially navigable waters, and environmentally sensitive areas, such as drinking water supplies or ecological reserves. The integrity management approach prioritizes resources to locations of highest consequence rather than applying uniform treatment to the entire pipeline network. PHMSA made integrity management programs mandatory for most oil pipeline operators with 500 or more miles of regulated pipeline as of March 31, 2001 (49 C.F.R. §195). Congress subsequently mandated the expansion of integrity management to natural gas pipelines, along with other significant changes to federal pipeline safety requirements, through a series of agency budget reauthorizations as discussed below.

PHMSA Reauthorization and Pipeline Safety Statutes

The PIPES Act of 2016 was preceded by a series of periodic pipeline safety statutes, each of which reauthorized funding for PHMSA's pipeline safety program and included other provisions related to PHMSA's authorities, administration, or regulatory activities.

Pipeline Safety Improvement Act of 2002

On December 12, 2002, President George W. Bush signed into law the Pipeline Safety Improvement Act of 2002 (P.L. 107-355). The act strengthened federal pipeline safety programs, state oversight of pipeline operators, and public education regarding pipeline safety.19 Among other provisions, P.L. 107-355 required operators of regulated natural gas pipelines in high-consequence areas to conduct risk analysis and implement integrity management programs similar to those required for oil pipelines.20 The act authorized DOT to order safety actions for pipelines with potential safety problems and increased violation penalties. The act streamlined the permitting process for emergency pipeline restoration by establishing an interagency committee, including the DOT, the Environmental Protection Agency, the Bureau of Land Management, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, and other agencies, to ensure coordinated review and permitting of pipeline repairs. The act required DOT to study ways to limit pipeline safety risks from population encroachment and ways to preserve environmental resources in pipeline rights-of-way. P.L. 107-355 also included provisions for public education, grants for community pipeline safety studies, "whistle blower" and other employee protection, employee qualification programs, and mapping data submission.

Pipeline Inspection, Protection, Enforcement, and Safety Act of 2006

On December 29, 2006, President Bush signed into law the Pipeline Inspection, Protection, Enforcement and Safety Act of 2006 (P.L. 109-468). The main provisions of the act address pipeline damage prevention, integrity management, corrosion control, and enforcement transparency. The act created a national focus on pipeline damage prevention through grants to states for improving damage prevention programs, establishing 811 as the national "call before you dig" one-call telephone number, and giving PHMSA limited "backstop" authority to conduct civil enforcement against one-call violators in states that have failed to conduct such enforcement. The act mandated the promulgation by PHMSA of minimum standards for integrity management programs for natural gas distribution pipelines.21 It also mandated a review of the adequacy of federal pipeline safety regulations related to internal corrosion control, and required PHMSA to increase the transparency of enforcement actions by issuing monthly summaries, including violation and penalty information, and a mechanism for pipeline operators to make response information available to the public.

Pipeline Safety, Regulatory Certainty, and Job Creation Act of 2011

On January 3, 2012, President Obama signed the Pipeline Safety, Regulatory Certainty, and Job Creation Act of 2011 (Pipeline Safety Act, P.L. 112-90). The act contains a broad range of provisions addressing pipeline safety. Among the most significant are provisions to increase the number of federal pipeline safety inspectors, require automatic shutoff valves for transmission pipelines, mandate verification of maximum allowable operating pressure for gas transmission pipelines, increase civil penalties for pipeline safety violations, and mandate reviews of diluted bitumen pipeline regulation. Altogether, the act imposed 42 mandates on PHMSA regarding studies, rules, maps, and other elements of the federal pipeline safety program. P.L. 112-90 authorized the federal pipeline safety program through the fiscal year ending September 30, 2015.

Protecting Our Infrastructure of Pipelines and Enhancing Safety Act of 2016

On June 22, 2016, President Obama signed the Protecting Our Infrastructure of Pipelines and Enhancing Safety Act of 2016 (PIPES Act, P.L. 114-183). As noted earlier, the act authorizes the federal pipeline safety program through FY2019. Among its other provisions, the act requires PHMSA to promulgate federal safety standards for underground natural gas storage facilities and grants PHMSA emergency order authority to address urgent "industry-wide safety conditions" without prior notice. The act also requires PHMSA to report regularly on the progress of outstanding statutory mandates, which are discussed later in this report.

Federal Energy Regulatory Commission

One area related to pipeline safety not under PHMSA's primary jurisdiction is the siting approval of interstate natural gas pipelines, which is the responsibility of the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC). Companies building interstate natural gas pipelines must first obtain from FERC certificates of public convenience and necessity. (FERC does not oversee oil pipeline construction.) FERC must also approve the abandonment of gas facility use and services. These approvals may include safety provisions with respect to pipeline routing, safety standards, and other factors.22 In particular, pipeline and aboveground facilities associated with a proposed pipeline project must be designed in accordance with PHMSA's safety standards regarding material selection and qualification, design requirements, and protection from corrosion.23

FERC and PHMSA cooperate on pipeline safety-related matters according to a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) signed in 1993. According to the MOU, PHMSA agrees to

- promptly alert FERC when safety activities may impact commission responsibilities,

- notify FERC of major accidents or significant enforcement actions involving pipelines under FERC's jurisdiction,

- refer to FERC complaints and inquiries by state and local governments and the public about environmental or certificate matters related to FERC-jurisdictional pipelines, and

- when requested by FERC, review draft mitigation conditions considered by the commission for potential conflicts with PHMSA's regulations.

Under the MOU, FERC agrees to

- promptly alert PHMSA when the commission learns of an existing or potential safety problem involving natural gas transmission facilities,

- notify PHMSA of future pipeline construction,

- periodically provide PHMSA with updates to the environmental compliance inspection schedule, and coordinate site inspections, upon request, with PHMSA officials,

- notify PHMSA when significant safety issues have been raised during the preparation of environmental assessments or environmental impact statements for pipeline projects, and

- refer to PHMSA complaints and inquiries made by state and local governments and the public involving safety matters related to FERC-jurisdictional pipelines.24

FERC may also serve as a member of PHMSA's Technical Pipeline Safety Standards Committee which determines whether proposed safety regulations are technically feasible, reasonable, cost-effective, and practicable.

In April 2015, FERC issued a policy statement to provide "greater certainty regarding the ability of interstate natural gas pipelines to recover the costs of modernizing their facilities and infrastructure to enhance the efficient and safe operation of their systems."25 FERC's policy statement was motivated by the commission's expectation that governmental safety and environmental initiatives could soon cause greater safety and reliability costs for interstate gas pipeline systems.26

National Transportation Safety Board

The National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) is an independent federal agency charged with determining the probable cause of transportation incidents—including pipeline releases—and promoting transportation safety. The board's experts investigate significant incidents, develop factual records, and issue safety recommendations to prevent similar events from reoccurring. The NTSB has no statutory authority to regulate transportation, however, and it does not perform cost-benefit analyses of regulatory changes; its safety recommendations to industry or government agencies are not mandatory. Nonetheless, because of the board's strong reputation for thoroughness and objectivity, over 82% of the NTSB's safety recommendations have been implemented across all transportation modes.27 In the pipeline sector, specifically, the NTSB's safety recommendations have led to changes in pipeline safety regulation regarding one-call systems before excavation ("Call Before You Dig"), use of pipeline internal inspection devices, facility response plan effectiveness, hydrostatic pressure testing of older pipelines, and other pipeline safety improvements.28

San Bruno Pipeline Incident Investigation

In August 2011, the NTSB issued preliminary findings and recommendations from its investigation of the San Bruno Pipeline incident. The investigation included testimony from pipeline company officials, government agency officials (PHMSA, state, and local), as well as testimony from other pipeline experts and stakeholders. The investigation determined that the pipeline ruptured due to a faulty weld in a pipeline section constructed in 1956. In addition to specifics about the San Bruno incident, the hearing addressed more general pipeline issues, including public awareness initiatives, pipeline technology, and oversight of pipeline safety by federal and state regulators.29 The NTSB's findings were highly critical of the pipeline operator (Pacific Gas and Electric, PG&E) as well as both the state and federal pipeline safety regulators. The board concluded that "the multiple and recurring deficiencies in PG&E operational practices indicate a systemic problem" with respect to its pipeline safety program.30 The board further concluded that

the pipeline safety regulator within the state of California, failed to detect the inadequacies in PG&E's integrity management program and that the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration integrity management inspection protocols need improvement. Because the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration has not incorporated the use of effective and meaningful metrics as part of its guidance for performance-based management pipeline safety programs, its oversight of state public utility commissions regulating gas transmission and hazardous liquid pipelines could be improved.

In an opening statement about the San Bruno incident report, the NTSB chairman summarized the board's findings as "troubling revelations … about a company that exploited weaknesses in a lax system of oversight and government agencies that placed a blind trust in operators to the detriment of public safety."31 The NTSB's final incident report concluded "that PHMSA's enforcement program and its monitoring of state oversight programs have been weak and have resulted in the lack of effective Federal oversight and state oversight."32

The NTSB issued 39 recommendations stemming from its San Bruno incident investigation, including 20 recommendations to the Secretary of Transportation and PHMSA. These recommendations included the following:

- conducting audits to assess the effectiveness of PHMSA's oversight of performance-based pipeline safety programs and state pipeline safety program certification,

- requiring pipeline operators to provide system-specific information to the emergency response agencies of the communities in which pipelines are located,

- requiring that automatic shutoff valves or remote control valves be installed in high consequence areas and in class 3 and 4 locations,33

- requiring that all natural gas transmission pipelines constructed before 1970 be subjected to a hydrostatic pressure test that incorporates a pressure spike test,34

- requiring that all natural gas transmission pipelines be configured so as to accommodate internal inspection tools, with priority given to older pipelines, and

- revising PHMSA's integrity management protocol to incorporate meaningful metrics, set performance goals for pipeline operators, and require operators to regularly assess the effectiveness of their programs using meaningful metrics.35

Marshall, MI, Pipeline Incident Investigation

In July 2012, the NTSB issued the final report of its investigation of the Marshall, MI, oil pipeline spill. In addition to finding management and operation failures by the pipeline operator, the report was critical of PHMSA for inadequate regulatory requirements and oversight of crack defects in pipelines, inadequate regulatory requirements for emergency response plans, generally, and inadequate review and approval of the response plan for this particular pipeline.36 The NTSB issued eight recommendations to the Secretary of Transportation and PHMSA, including

- auditing the business practices of PHMSA's onshore pipeline facility response plan programs, including reviews of response plans and drill programs, to correct deficiencies,

- allocating sufficient resources to ensure that PHMSA's facility response plan program meets all of the requirements of the Oil Pollution Act of 1990,

- clarifying and strengthening federal regulation related to the identification and repair of pipeline crack defects,

- issuing advisory bulletins to all hazardous liquid and natural gas pipeline operators describing the circumstances of the accident in Marshall, asking them to take appropriate action to eliminate similar deficiencies, to identify deficiencies in facility response plans, and to update these plans as necessary,

- developing requirements for team training of control center staff involved in pipeline operations similar to those used in other transportation modes,

- strengthening operator qualification requirements, and

- harmonizing onshore oil pipeline response planning requirements with those of the U.S. Coast Guard and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency for oil and petroleum products facilities to ensure that operators have adequate resources for worst-case discharges.37

Merrimack Valley Pipeline Incident Investigation

In October 2018, the NTSB issued a preliminary report of its investigation into the Merrimack Valley natural gas fires and explosions, which affected the communities of Lawrence, Andover, and North Andover, MA. The report concluded, based on an initial investigation, that the natural gas releases were caused by excessive pressure in a local distribution main during a cast iron pipeline replacement project. Due to an erroneous work order, pipeline workers improperly bypassed critical pipeline pressure-sensing lines. Without an accurate sensor signal from the bypassed pipeline segment, the pipeline pressure regulators allowed high-pressure gas into the distribution lines supplying homes and businesses—many of which failed and released natural gas as a result.38 The NTSB's formal incident investigation continues, so the agency has not yet released a final accident report. However, in response to its initial findings, the NTSB made a preliminary recommendation to the Commonwealth of Massachusetts to eliminate its professional engineer license exemption for public utility work and to require a professional engineer's seal on public utility engineering drawings.39 The NTSB also made recommendations to the natural gas distribution utility regarding its design and operating practices. It made no recommendations to PHMSA.

Other Investigations

The NTSB has made recommendations to PHMSA as a result of other pipeline incident investigations. Detailed discussion of NTSB findings and recommendations, including those described above, are publicly available in the NTSB's docket management system.40 In addition, in January 2015, the NTSB released a safety study examining integrity management of natural gas transmission pipelines in high consequence areas. The study identified several areas of potential safety improvement among such facilities

- expanding and improving PHMSA guidance to both operators and inspectors for the development, implementation, and inspection of operators' integrity management programs,

- expanding the use of in-line inspection, especially for intrastate pipelines,

- eliminating the use of direct assessment as the sole integrity assessment method,

- evaluating the effectiveness of the approved risk assessment approaches,

- strengthening aspects of inspector training,

- developing minimum professional qualification criteria for all personnel involved in integrity management programs, and

- improving data collection and reporting, including geospatial data.41

PHMSA maintains a list of NTSB's pipeline safety recommendations directed at the agency which are currently open. As of September 11, 2018, there were 25 open recommendations dating back to 2011.42 In many cases, NTSB has classified these recommendations as "Open—Acceptable Response" because they are being incorporated satisfactorily in ongoing PHMSA rulemakings, further discussed below. However, a few recommendations are classified as "Open—Unacceptable response," because NTSB is not satisfied with PHMSA's actions to implement them.

PHMSA's Role in Pipeline Security

Pipeline safety and security are distinct issues involving different threats, statutory authorities, and regulatory frameworks. Nonetheless, pipeline safety and security are intertwined in some respects—and PHMSA is involved in both.

The Department of Transportation played the leading role in pipeline security through the late 1990s. Presidential Decision Directive 63 (PDD-63), issued during the Clinton Administration, assigned lead responsibility for pipeline security to DOT.43 These responsibilities fell to the Office of Pipeline Safety, at that time a part of DOT's Research and Special Programs Administration, because the agency was already addressing some elements of pipeline security in its role as safety regulator.44 The DOT's pipeline (and LNG) safety regulations already included provisions related to physical security, such as requirements to protect surface facilities (e.g., pumping stations) from vandalism and unauthorized entry.45 Other regulations required continuing surveillance, patrolling pipeline rights-of-way, damage prevention, and emergency procedures.46

In the early 2000s, OPS conducted a vulnerability assessment to identify critical pipeline facilities and worked with industry groups and state pipeline safety organizations "to assess the industry's readiness to prepare for, withstand and respond to a terrorist attack.... "47 Together with DOE and state pipeline agencies, OPS promoted the development of consensus standards for security measures tiered to correspond with the five levels of threat warnings issued by the Office of Homeland Security.48 OPS also developed protocols for inspections of critical facilities to ensure that operators implemented appropriate security practices. To convey emergency information and warnings, OPS established a variety of communication links to key staff at the most critical pipeline facilities throughout the country. OPS also began identifying near-term technology to enhance deterrence, detection, response, and recovery, and began seeking to advance public and private sector planning for response and recovery.49

On September 5, 2002, OPS circulated formal guidance developed in cooperation with the pipeline industry associations defining the agency's security program recommendations and implementation expectations. This guidance recommended that operators identify critical facilities, develop security plans consistent with prior trade association security guidance, implement these plans, and review them annually.50 While the guidance was voluntary, OPS expected compliance and informed operators of its intent to begin reviewing security programs and to test their effectiveness.51

PHMSA Cooperation with TSA

In November 2001, President Bush signed the Aviation and Transportation Security Act (P.L. 107-71) establishing the Transportation Security Administration (TSA) within DOT. According to TSA, the act placed DOT's pipeline security authority (under PDD-63) within TSA. The act specified for TSA a range of duties and powers related to general transportation security, such as intelligence management, threat assessment, mitigation, security measure oversight, and enforcement. On November 25, 2002, President Bush signed the Homeland Security Act of 2002 (P.L. 107-296) creating the Department of Homeland Security (DHS). Among other provisions, the act transferred the Transportation Security Administration from DOT to DHS (§403). On December 17, 2003, President Bush issued Homeland Security Presidential Directive 7 (HSPD-7), clarifying executive agency responsibilities for identifying, prioritizing, and protecting critical infrastructure.52 HSPD-7 maintained DHS as the lead agency for pipeline security (paragraph 15), and instructed DOT to "collaborate in regulating the transportation of hazardous materials by all modes (including pipelines)" (paragraph 22h).

In 2004, the DOT and DHS entered into a memorandum of understanding concerning their respective security roles in all modes of transportation. The MOU notes that DHS has the primary responsibility for transportation security with support from the DOT, and establishes a general framework for cooperation and coordination. The MOU states that "specific tasks and areas of responsibility that are appropriate for cooperation will be documented in annexes ... individually approved and signed by appropriate representatives of DHS and DOT."53 On August 9, 2006, the departments signed an annex "to delineate clear lines of authority and responsibility and promote communications, efficiency, and nonduplication of effort through cooperation and collaboration between the parties in the area of transportation security."54

In January 2007, the PHMSA Administrator testified before Congress that the agency had established a joint working group with TSA "to improve interagency coordination on transportation security and safety matters, and to develop and advance plans for improving transportation security," presumably including pipeline security.55 According to TSA, the working group developed a multiyear action plan specifically delineating roles, responsibilities, resources and actions to execute 11 program elements: identification of critical infrastructure/key resources, and risk assessments; strategic planning; developing regulations and guidelines; conducting inspections and enforcement; providing technical support; sharing information during emergencies; communications; stakeholder relations; research and development; legislative matters; and budgeting.56

P.L. 109-468 required the DOT Inspector General (IG) to assess the pipeline security actions taken by the DOT in implementing its 2004 MOU with the DHS (§23). The Inspector General published this assessment in May 2008. The IG report stated,

PHMSA and TSA have taken initial steps toward formulating an action plan to implement the provisions of the pipeline security annex.... However, further actions need to be taken with a sense of urgency because the current situation is far from an "end state" for enhancing the security of the Nation's pipelines.57

The report recommended that PHMSA and TSA finalize and execute their security annex action plan, clarify their respective roles, and jointly develop a pipeline security strategy that maximizes the effectiveness of their respective capabilities and efforts.58 According to TSA, working with PHMSA "improved drastically" after the release of the IG report; the two agencies began to maintain daily contact, share information in a timely manner, and collaborate on security guidelines and incident response planning.59 Consistent with this assertion, in March 2010, TSA published a Pipeline Security and Incident Recovery Protocol Plan which lays out in detail the separate and cooperative responsibilities of the two agencies with respect to a pipeline security incident. Among other notes, the plan states,

DOT has statutory tools that may be useful during a security incident, such as special permits, safety orders, and corrective action orders. DOT/PHMSA also has access to the Regional Emergency Transportation Coordinator (RETCO) Program…. Each RETCO manages regional DOT emergency preparedness and response activities in the assigned region on behalf of the Secretary of Transportation.60

The plan also refers to the establishment of an Interagency Threat Coordination Committee established by TSA and PHMSA to organize and communicate developing threat information among federal agencies that may have responsibility for pipeline incident response.61

DOT has continued to cooperate with TSA on pipeline security in recent years. For example, TSA coordinated with DOT and other agencies to address ongoing vandalism and sabotage against critical pipelines by environmental activists in 2016.62 In April 2016, the Director of TSA's Surface Division testified about her agency's relationship with DOT:

TSA and DOT co-chair the Pipeline Government Coordinating Council to facilitate information sharing and coordinate on activities including security assessments, training, and exercises. TSA and DOT's Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA) work together to integrate pipeline safety and security priorities, as measures installed by pipeline owners and operators often benefit both safety and security.63

In December 2016, PHMSA issued an Advisory Bulletin "in coordination with" TSA regarding cybersecurity threats to pipeline Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition (SCADA) systems.64 In July 2017, the two agencies collaborated on a web-based portal to facilitate sharing sensitive but unclassified incident information among federal agencies with pipeline responsibilities.65 In February 2018, the Director of TSA's Surface Division again testified about cooperation with PHMSA, stating "TSA works closely with [PHMSA] for incident response and monitoring of pipeline systems," although she did not provide specific examples.66

Key Policy Issues

The 116th Congress may focus on several key issues in its continuing oversight of federal pipeline safety and as it considers PHMSA's reauthorization, including incomplete statutory mandates, adequacy of PHMSA staffing, state program oversight, aging pipeline infrastructure, and PHMSA's role in pipeline security. These issues are discussed in the following sections.

Overdue PHMSA Statutory Mandates

Congress has used reauthorizations to impose on PHMSA various mandates regarding standards, studies, and other elements of pipeline safety regulation—usually in response to major pipeline accidents. The Pipeline Safety, Regulatory Certainty, and Job Creation Act of 2011 (P.L. 112-90) and the PIPES Act of 2016 (P.L. 114-183) together included 61 such mandates. As of March 5, 2019, according to PHMSA, the agency had completed 34 of 42 mandates under P.L. 112-90 and 16 of 19 mandates under P.L. 114-183.67 Some Members of Congress are concerned that major mandates remain unfulfilled years beyond the deadlines specified in statute. They have expressed frustration with PHMSA's failure to fulfill its statutory obligations, arguing that it delays important new regulations, undermines public confidence in pipeline safety, and does not allow Congress to evaluate the effectiveness of prior mandates as it considers PHMSA's next reauthorization.68 Among the overdue mandates, Congress has focused on several key regulations (rules) with potentially significant impacts on pipeline operations nationwide.

Safety of Gas Transmission Pipelines Rule

This rulemaking would require operators to (1) reconfirm pipeline maximum allowable operating pressure and (2) test the material strength of previously untested gas transmission pipelines in high-consequence areas (P.L. 112-90 §23(c-d)). The statutory deadline for PHMSA to finalize these two rules was July 3, 2013. The rulemaking also would address the expansion of "integrity management" programs for gas transmission pipelines beyond high-consequence areas (P.L. 112-90 §5(f)). Integrity management provides for continual evaluation of pipeline condition; assessment of risks; inspection or testing; data analysis; and follow-up repair; as well as preventive or mitigative actions. The deadline for PHMSA to finalize the integrity management provisions was January 3, 2015. The rulemaking also would address the application of existing regulations to currently unregulated gathering lines (P.L. 112-90 §21(c)).

PHMSA issued a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking incorporating the above provisions, and other requirements, on June 7, 2016.69 However, PHMSA subsequently decided to split its efforts into three separate rulemakings to facilitate completion. PHMSA anticipates publication of a final rule for the maximum allowable operating pressure and material testing provisions in July 2019.70 PHMSA anticipates publication of separate final rules for the integrity management provisions and for the gathering line provisions in December 2019.71

Safety of Hazardous Liquids Pipelines Rule

Among other requirements, this rulemaking would require leak detection systems, where practicable, for hazardous liquids (i.e., oil and refined fuel) pipelines and would set standards for leak detection capability (P.L. 112-90 §8(b)). It also would address the expansion of integrity management for liquids pipelines beyond high-consequence areas (P.L. 112-90 §5(f)). The deadlines for PHMSA to finalize these rules were, respectively, January 3, 2014, and January 3, 2015. The rulemaking also would require additional integrity assessment measures for certain underwater onshore liquids pipelines (P.L. 114-183 §25). PHMSA issued a prepublication final rule on January 13, 2017, but withdrew it on January 24, 2017, for further review in compliance with the "Memorandum for the Heads of Executive Departments and Agencies" issued by the White House.72 PHMSA anticipates publication of a final rule in May 2019.73

Amendments to Parts 192 and 195

This rulemaking, which refers to Title 49 of the Code of Federal Regulations, involves requirements for pipeline valve installation and minimum rupture detection standards. These measures are intended to enhance the ability of pipeline operators to quickly stop the flow of a commodity (e.g., oil) in case of an unintended release by installing automatic or remote-controlled valves (P.L. 112-90 §4). The rulemaking also would outline performance standards for pipeline rupture detection (P.L. 112-90 §8(b)). The deadline for PHMSA to finalize these rules was January 3, 2014. PHMSA anticipates issuing a proposed rule in August 2019.74

Underground Natural Gas Storage Facilities

This rulemaking would set minimum federal safety standards for underground natural gas storage facilities (P.L. 114-183 §12). The deadline for PHMSA to finalize this rule was June 22, 2018. PHMSA issued an interim final rule on December 19, 2016.75 However, the agency temporarily suspended certain enforcement actions on June 20, 2017, and reopened the rule to public comment until November 20, 2017.76 DOT anticipates publishing the final rule in August 2019.77

Emergency Order Authority

This rulemaking would implement PHMSA's new authority to issue emergency orders, which would apply to all operators and/or pipeline systems to abate an imminent hazard (P.L. 114-183 §16). The deadline for PHMSA to finalize this rule was March 22, 2017. The agency issued an interim final rule on October 14, 2016.78 PHMSA anticipates publication of a final rule in March 2019.79

PHMSA Rulemaking Oversight and Agency Response

In response to questions during a 2015 hearing about overdue statutory mandates, a PHMSA official testified that rulemaking delays at that time did not reflect a lack of commitment but rather their complexity, the agency's rulemaking process, and limited staff resources.80 A 2016 audit report by the DOT Inspector General concluded that PHMSA lacked "sufficient processes, guidance, and oversight for implementing mandates" in a timely manner.81 On June 21, 2018, the current PHMSA administrator testified that the agency had adequate staffing and funding for its rulemaking activities and was working to streamline the agency's rulemaking process to accelerate finalization of the overdue rules. He stated that PHMSA would prioritize rulemaking in three areas: the safety of hazardous liquid pipelines, the safety of gas transmission and gathering pipelines, and pipeline rupture detection and automatic shutoff valves.82

Staffing Resources for Pipeline Safety

The U.S. pipeline safety program employs a combination of federal and state staff to implement and enforce federal pipeline safety regulations. To date, PHMSA has relied heavily on state agencies for pipeline inspections, with over 70% of inspectors being state employees. As the PHMSA administrator remarked in 2018,

PHMSA faces a manpower issue. It is obvious that an agency that employs about 536 people cannot oversee 2.7 million miles of pipeline all by itself. In fact, PHMSA makes no attempt to do so. Most actual safety inspections are performed by our state partners.83

Nonetheless, some in Congress have criticized inspector staffing at PHMSA for being insufficient to cover pipelines under the agency's jurisdiction. In considering PHMSA staff levels, issues of interest have been the number of federal inspectors and the agency's historical use of staff funding.

PHMSA Inspection and Enforcement Staff

In FY2019, PHMSA is funded for 308 full-time equivalent (FTE) employees in pipeline safety. As noted earlier, PHMSA employed 290 full-time equivalent staff in pipeline safety, including 145 inspectors, as of March 8, 2019. According to PHMSA officials, the agency continues hiring and anticipates employing additional staff in the second half of the fiscal year. While the President's requested budget authority for PHMSA's pipeline safety program in FY2020 is less than the FY2019 budget authority, it projects only a small reduction in funded staff. The budget includes an estimate of 306 FTEs for FY2020, two fewer FTEs than the prior year.84 According to PHMSA, these two positions, which support pipeline safety data analysis and information technology, are to be transferred to DOT's Office of the Chief Information Officer as part of a centralization of all systems and technology within that office.85

If PHMSA's pipeline safety staffing were to be funded at the level of the President's FY2020 budget request, it would maintain the significant increase in PHMSA staff funding (mostly for inspectors) appropriated since FY2014 (Figure 4). However, to the extent it reduces funding for grants available to the states, it potentially could reduce the number of staff in state pipeline safety agencies. It would also be a step back, in terms of funding, from the long-term expansion of PHMSA's pipeline safety program begun over 20 years ago in response to a series of pipeline accidents, the terrorist attacks of 9/11, implementation of PHMSA's integrity management regulations, and the boom in U.S. shale gas and oil production.

PHMSA officials have offered a number of reasons for the persistent shortfall in inspector staffing. These reasons include a scarcity of qualified inspector job applicants, delays in the federal hiring process during which applicants accept other job offers, and PHMSA inspector turnover—especially to pipeline companies, which often hire away PHMSA inspectors for their corporate safety programs. Because PHMSA pipeline inspectors are extensively trained by the agency (typically for two years before being allowed to operate independently), they are highly valued by pipeline operators seeking to comply with federal safety regulations. The agency has stated that it is challenged by industry recruitment of the same candidates it is recruiting, especially with the rapid development of unconventional oil and gas shales, for which the skill sets PHMSA seeks (primarily engineers) have been in high demand.86 A 2017 DOT Inspector General (IG) report supported PHMSA's assertions about industry-specific hiring challenges and confirmed "a significant gap between private industry and Federal salaries for the types of engineers PHMSA hires."87

To overcome its pipeline inspector hiring challenges, PHMSA has implemented a "robust recruitment and outreach strategy" that includes certain noncompetitive hiring authorities (e.g., Veterans Employment Opportunities Act) and a fellows program. The agency also has offered recruitment, relocation and retention incentives, and a student loan repayment program. In addition to posting vacancy announcements on USAJOBS, PHMSA has posted job announcements using social media (Twitter and LinkedIn), has conducted outreach to professional organizations and veterans groups, and has attended career fairs and on-campus hiring events.88 PHMSA states that it has been "working hard to hire and retain inspector staff" but continues to experience staff losses due to an aging workforce and continued difficulty hiring and retaining engineers and technical staff because of competition from the oil and natural gas industry.89

Although PHMSA has taken concrete actions in recent years to shore up its workforce, there may still be room for improvement. Notably, the IG report concluded in 2017 that PHMSA did "not have a current workforce management plan or fully use retention tools," although the agency had improved how it integrates new employees in the agency.90 According to the IG, PHMSA concurred with the report's workforce management recommendations and proposed appropriate action plans.91 On a related issue, a 2018 study by the Government Accountability Office (GAO) reports that "PHMSA has not planned for future workforce needs for interstate pipeline inspections," and, in particular, has not assessed the resources and benefits available from its state partners.92 The GAO concluded that without this type of forward-looking analysis, "PHMSA cannot proactively plan for future inspection needs to ensure that federal and state resources are in place to provide effective oversight of interstate pipelines."93 According to GAO, PHMSA has concurred with its recommendation to develop a workforce plan for interstate pipeline inspections. What impact PHMSA's subsequent actions may have on its staff recruitment, retention, and deployment is an open question.

Direct-Hire Authority

One specific remedy PHMSA has pursued in its efforts to recruit pipeline inspectors is to seek direct-hire authority (DHA) from the Office of Personnel Management (OPM). This authority can expedite hiring, for example, by eliminating competitive rating and ranking, or not requiring veterans' preference. OPM can grant DHA to federal agencies in cases of critical hiring need or a severe shortage of candidates.94

In its 2013 appropriations report, the House Appropriations Committee stated

The Committee is aware of several challenges PHMSA faces in hiring pipeline safety inspectors. One such challenge is the delay caused by the federal hiring process, which is compounded by other market dynamics. The Committee encourages the Office of Personnel Management to give strong consideration to PHMSA's request for direct-hire authority for its pipeline safety inspection and enforcement personnel. Such authority may enable PHMSA to increase its personnel to authorized levels and thereby demonstrate the need for additional resources.95

The same language appears in the committee's 2014 appropriations report. Consistent with the committee's recommendations, PHMSA applied to the OPM for direct-hire authority in April 2015 but was denied. According to PHMSA, the OPM informed agency officials of the denial verbally, but did not provide a formal, written explanation for the denial at the time.96

In 2016, the PHMSA administrator reiterated the agency's desire for DHA, stating that it "would complement our recruitment efforts by reducing the agency's time to hire from more than 100 days to less than 30 days."97 P.L. 114-183 did not grant PHMSA direct-hire authority, but did allow the agency to apply to the OPM for it upon identification of a period of macroeconomic and pipeline industry conditions creating difficulty in filling pipeline safety job vacancies (§9b). However, the aforementioned IG report concluded that direct hire authority might not provide PHMSA with the needed tools to recruit staff more effectively. According to the IG, while this authority might speed hiring of new employees, "it is not clear how it alone would resolve long-standing staffing challenges such as competing with a well-paying industry over a limited talent pool."98

State Pipeline Safety Program Oversight

In the wake of several major safety incidents involving facilities under the jurisdiction of state pipeline safety regulators, some state programs have come under scrutiny regarding their overall effectiveness. After the San Bruno pipeline incident, the California state pipeline safety program—which had regulatory responsibility for the pipeline that ruptured—was criticized by the NTSB for its failure to detect the pipeline's problems. The NTSB was also critical of PHMSA's oversight of the state because the agency had not "incorporated the use of effective and meaningful metrics as part of its guidance for performance-based management" of state pipeline safety programs.99 A 2014 investigation by the DOT Office of Inspector General assessed the effectiveness of PHMSA's state program oversight as recommended by the NTSB. The IG report stated

PHMSA's oversight of State pipeline safety programs is not sufficient to ensure States comply with program evaluation requirements and properly use suspension grant funds. Lapses in oversight have resulted in undisclosed safety weaknesses in State programs.100

The IG report recommended that PHMSA "take actions to further refine its policies and procedures for managing the program, including its guidelines to the States and improve its oversight to ensure States fulfill their role in pipeline safety."101 The report made seven specific programmatic recommendations to achieve these goals. In its response to a draft version of the IG report, PHMSA officials concurred or partially concurred with all of the IG reports' recommendations, describing actions it had taken to address the IG's concerns.102 The IG report therefore considered all but two of its recommendations resolved, but urged PHMSA to reconsider and clarify its response to the remaining two recommendations. These recommendations pertained to PHMSA's staffing formula and its annual evaluations of inspection procedures among the states.103

The Aliso Canyon and Merrimack Valley incidents again focused attention on the oversight and effectiveness of state pipeline safety programs. For example, during the Aliso Canyon incident, PHMSA expressed concern to state regulators about aspects of the state's safety oversight, including its review of historical well records showing facility anomalies and requirements for safety contingency plans to protect workers, the public, and property.104 A subsequent federal interagency task force concluded that "the practices for monitoring and assessing leaks and leak potential at the Aliso Canyon facility were inadequate to maintain safe operations."105 In the Merrimack Valley case, state legislators reportedly criticized Massachusetts' pipeline safety regulators for insufficient staffing and inadequate oversight of pipeline facilities.106 However, PHMSA's annual evaluation of the state's pipeline safety program—conducted the month before the natural gas releases—gave the state program a rating of 97.4 out of 100 maximum points. 107 PHMSA's evaluation did note a shortfall in inspector staffing, which could impact the agency's inspection schedule, and that the state agency was working to hire additional inspectors.108 In light of these incidents, and the IG's prior recommendations, Congress may reexamine the adequacy of PHMSA's oversight of its state pipeline safety partners.

Aging Pipeline Infrastructure

The NTSB listed the safe shipment of hazardous materials by pipeline among its 2019-2020 Most Wanted List of Transportation Safety Improvements, stating "as infrastructure ages, the risk to the public from pipeline ruptures also grows."109 Likewise, Congress has ongoing concern about the safety of older transmission pipelines—a key factor in San Bruno—and in the replacement of leaky and deteriorating cast iron pipe in natural gas distribution systems—a key factor in Merrimack Valley.110 The construction work in Merrimack Valley, which led to the natural gas release, was part of a cast iron pipe replacement project. (Age was also a factor in the failure of the well casing which led to the uncontrolled natural gas release at the Aliso Canyon facility.) According to the American Gas Association and other stakeholders, antiquated cast iron pipes in natural gas distribution systems, many over 50 years old, "have long been recognized as warranting attention in terms of management, replacement and/or reconditioning."111 Old distribution pipes have also been identified as a significant source of methane leakage, which poses safety risks and contributes to U.S. greenhouse gas emissions.112 In April 2015, then-Secretary of Energy Ernest Moniz reportedly stated that safety and environmental risks from old, leaky distribution lines were "a big issue."113

Natural gas distribution system operators all have ongoing programs for the replacement of antiquated pipes in their systems, although some are constrained by state regulators who face challenges considering significant rate increases to pay for these upgrades. According to the Department of Energy, the total cost of replacing cast iron and bare steel distribution pipes is approximately $270 billion.114 Practical barriers, such as urban excavation and disruption of gas supplies, also limit annual replacement. Although the federal role in natural gas distribution systems is limited, because they are under state jurisdiction, there have been prior proposals in Congress and in the QER to provide federal support for the management and replacement of old cast iron pipe.115

The Pipeline Safety Act mandated a survey (with follow-up every two years thereafter) of pipeline operator progress in adopting and implementing plans for the management and replacement of cast iron pipes (§7(a)). The Merrimack Valley incident may refocus attention on PHMSA's regulation of pipe replacement (currently voluntary), pipeline modernization projects and work packages, older pipeline records, safety management systems, and other issues related to aging pipelines.116 Congress also may examine the industry's overall progress in addressing the safety of antiquated distribution lines and opportunities for federal support of those efforts.

PHMSA and Pipeline Security

Ongoing physical and cyber threats against the nation's pipelines since passage of the PIPES Act have heightened concerns about the security risks to these pipelines. In a December 2018 study, GAO stated that since the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, "new threats to the nation's pipeline systems have evolved to include sabotage by environmental activists and cyber attack or intrusion by nations."117 Recent oversight of federal pipeline security activities has included discussion of PHMSA's role in pipeline security.

While PHMSA reports cooperation with TSA in pipeline security under the terms of the pipeline security annex and subsequent collaboration, questions remain regarding exactly what this cooperation entails and the ongoing roles of the two agencies. Congress has considered in the past whether the TSA-PHMSA pipeline security annex optimally aligns staff resources and capabilities across both agencies to fulfill the nation's overall pipeline safety and security missions.118 More recently, some in the pipeline industry have questioned PHMSA's focus on, and ongoing commitment to, pipeline security issues, especially in cybersecurity.119

In the 116th Congress, the Pipeline and LNG Facility Cybersecurity Preparedness Act (H.R. 370, S. 300) would require the Secretary of Energy to enhance coordination among "appropriate Federal agencies," state government agencies, and the energy sector in pipeline security; coordinate incident response and recovery; support the development of pipeline cybersecurity applications, technologies, demonstration projects, and training curricula; and provide technical tools for pipeline security. What role PHMSA might play in any future pipeline security initiatives, and what resources it might require to perform that role, may be a consideration for Congress.

Conclusion

Both government and industry have taken numerous steps to improve pipeline safety over the last 10 years. In 2016, the Association of Oil Pipe Lines stated that "the oil and natural gas industry is committed to achieving zero incidents throughout our operations."120 Likewise, the American Gas Association, which represents investor-owned natural gas distribution companies, recently stated that "safety is the core value for America's natural gas utilities."121 Nonetheless, major oil and natural gas pipeline accidents continue to occur. Both Congress and the NTSB have called for additional regulatory measures to reduce the likelihood of future pipeline accidents.

Past PHMSA reauthorizations included expansive pipeline safety mandates, such as requirements for the agency to impose integrity management programs, significantly increase inspector staffing, or regulate underground natural storage. In light of the most recent pipeline accidents or security incidents, Congress may consider new regulatory mandates on PHMSA or may impose new requirements directly on the pipeline industry. However, a number of broad pipeline safety rulemakings and many NTSB recommendations remain outstanding, and others have not been in place for long, so their effectiveness in improving pipeline safety have yet to be determined. As Congress continues its oversight of the federal pipeline safety program, an important focus may be the practical effects of the many changes being made to particular aspects of PHMSA's pipeline safety regulations.

In addition to the specific issues highlighted in this report, Congress may assess how the various elements of U.S. pipeline safety activity fit together in the nation's overall strategy to protect the public and the environment. Pipeline safety necessarily involves various groups: federal and state agencies, pipeline associations, large and small pipeline operators, and local communities. Reviewing how these groups work together to achieve common goals could be an overarching concern for Congress.