Introduction

The United States was the driving proponent of NATO's creation in 1949 and has been the unquestioned leader of the alliance as it has evolved from a regionally focused collective defense organization of 12 members to a globally engaged security organization of 29 members. Successive U.S. Administrations have viewed U.S. leadership of NATO as a cornerstone of U.S. national security strategy, bringing benefits ranging from peace and stability in Europe to the political and military support of 28 allies, including many of the world's most advanced militaries.

For almost as long as NATO has been in existence, it also has faced criticism. One chief concern of critics in the United States, including some Members of Congress, has been that European allies' reliance on U.S. security guarantees have fostered an imbalanced and unsustainable "burdensharing" arrangement by which the United States carries an unfair share of the responsibility for ensuring European security. President Donald Trump has amplified these concerns, and his assertions that NATO is a "bad deal" have caused some analysts and policymakers to reassess the costs and benefits to the United States of its long-standing leadership of the alliance.1

Although successive U.S. presidents have called on the allies to increase defense spending, none has done so as stridently as President Trump. He is also the first U.S. president to publicly suggest that the United States could modify its commitment to NATO should the allies fail to meet agreed defense spending targets.2 Trump Administration officials stress that the United States remains committed to NATO, as articulated in the Administration's National Security and Defense Strategies. They highlight the Administration's successful efforts in 2017 and 2018 to substantially increase funding for the U.S. force presence in Europe. President Trump's supporters, including some Members of Congress, also argue that Trump's forceful statements have succeeded in securing defense spending increases across the alliance that were not forthcoming under his predecessors.

Nevertheless, many supporters of NATO, including some allied governments, continue to question the President's commitment to the alliance and worry that his condemnations could damage NATO cohesion and credibility. In the face of these concerns, Congress has demonstrated significant bipartisan support for NATO and U.S. leadership of the alliance. In January 2019, following reports that the President has considered seeking to withdraw the United States from NATO, the House of Representatives passed legislation reaffirming U.S. support for the alliance and limiting the President's authority to withdraw (H.R. 676, passed by a vote of 357-22); similar legislation has been introduced in the Senate (S.J.Res. 4).3

Many analysts view the bipartisan, House-Senate invitation to NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg to address a joint session of Congress on April 3, 2019, as an additional sign of continued congressional support. At the same time, Congress continues to assess NATO's utility and value to the United States and some Members are concerned about several key challenges that continue to face the alliance, including burdensharing, managing relations with Russia, and divergent threat perceptions within the alliance.

This report provides context for ongoing discussions about NATO's value to the United States and the extent to which NATO serves U.S. strategic interests. A historical overview focuses on the perceived benefits to the United States of NATO membership from NATO's founding to the present day. Sections on burdensharing and Russia address key challenges facing the alliance. The report concludes with a discussion of U.S. policy and considerations for Congress. An appendix provides data on defense spending by NATO members.

Historical Context: NATO's Evolution4

Broadly speaking, NATO has evolved through four phases since its inception in 1949:

- the Cold War era between 1949 and 1991;

- the post-Cold War transformation of the 1990s, marked by the start of NATO enlargement to former Warsaw Pact countries and debates over "out-of-area" military operations prompted by wars in the Western Balkans;

- the post-September 11, 2001, focus on crisis management and stabilizing Afghanistan; and

- since 2014, a renewed focus on deterring Russia and heightened concern about threats emanating from the Middle East and North Africa.

NATO's current Strategic Concept, adopted in 2010, articulates three broad activities for NATO: collective defense, crisis management, and cooperative security.5 The far-reaching nature of these priorities reflects both the increasingly complex global security environment and the diverse range of threat perceptions inherent in an alliance of 29 members. Some observers express concern that NATO may lack the collective political will and the requisite military capacities to fulfill these objectives, which in turn could lead to an erosion of political and public support for the alliance. Others counter that despite such concerns, NATO's capacity to enhance security for its member states remains unparalleled and that the alliance has demonstrated flexibility in adapting to meet a wide range of evolving security threats.

The Cold War: Defending Against the Soviet Union

In the aftermath of World War II, the United States designed NATO to provide a framework for coordinating U.S., Canadian, and West European defense against the threat from the Soviet Union and the Warsaw Pact.6 NATO's foundational mutual defense clause—enshrined in Article 5 of NATO's founding North Atlantic Treaty—sought to prevent both further Soviet expansion and the U.S.S.R's ability to fracture the alliance (see text box). An additional objective was to bind the formerly warring European states (including France, the UK, Italy, and, crucially, West Germany) in a security arrangement that could prevent the outbreak of future hostilities among them. As NATO's first Secretary General, Lord Ismay reportedly quipped, NATO was created "to keep the Soviet Union out, the Americans in, and the Germans down."7

|

Article 5 of the North Atlantic Treaty The Parties agree that an armed attack against one or more of them in Europe or North America shall be considered an attack against them all and consequently they agree that, if such an armed attack occurs, each of them, in exercise of the right of individual or collective self-defense recognized by Article 51 of the Charter of the United Nations, will assist the Party or Parties so attacked by taking forthwith, individually and in concert with the other Parties, such action as it deems necessary, including the use of armed force, to restore and maintain the security of the North Atlantic area. |

Throughout the Cold War, U.S. leaders assessed that the strategic benefits of defending Western Europe from an expansionist Soviet Union, building interoperable European militaries, and preventing renewed hostilities among Western European states outweighed the cost of maintaining a vast U.S. military presence in Europe that included more than 400,000 U.S. troops as well as U.S. nuclear weapons. For European allies, the benefits of the U.S. security umbrella were perceived largely as outweighing the costs of hosting U.S. military facilities, fulfilling defense and other requirements determined by the United States, and a loss of strategic autonomy.8

The 1990s: Enlargement, the "Peace Dividend," and "Out-of-Area" Operations

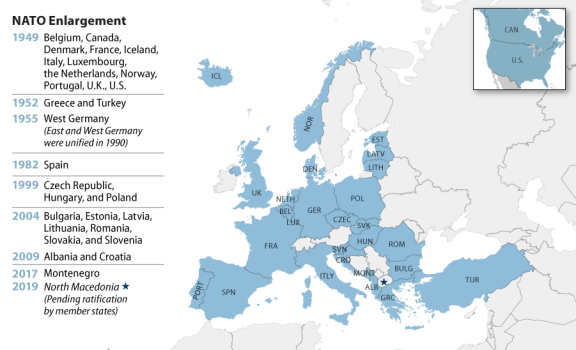

With the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, the subsequent reunification of Germany, and the collapse of the Soviet Union, some in NATO questioned whether or in what form NATO should continue to exist. The United States and other allied leaders determined that the alliance could still play an important role in fulfilling shared security objectives beyond Cold War territorial defense. Chiefly, the allies agreed to a new nonconfrontational posture based on a drawdown of military forces and pursuit of partnership with former adversaries in the Warsaw Pact. A focus on spreading peace, stability, and democracy throughout Europe led to the accession of 10 new member states in 1999 and 2004 (see Figure 1). Although NATO and Russia took the first steps toward partnership during this period, leaders in Moscow remained uneasy with NATO and would later characterize NATO enlargement towards Russian borders as a major security threat.

The wars in the Western Balkans in the 1990s spurred debate within NATO about so-called "out of area" operations. During the Cold War, NATO's military posture had been limited to defending allied territory. The United States and other allies now argued that to remain relevant, NATO must be prepared to confront security threats outside of alliance territory—"out of area or out of business" became NATO's de facto mantra. NATO's military intervention in the Western Balkans—beginning in Bosnia in 1995—was a first step in this direction and a monumental one for Germany, which had been constitutionally barred from deploying its forces abroad since World War II. At the behest of the United States, NATO's 1999 Strategic Concept articulated a broader definition of security and identified new security threats, including terrorism, ethnic conflict, human rights abuses, political instability, and the spread of nuclear, biological, and chemical weapons.

At the same time, the changed European security environment and the so-called "peace dividend" marked the beginning of reductions in European defense spending and military capabilities that created tensions in later years. The United States also embarked on a sharp reduction of U.S. forces in Europe.

|

|

Source: CRS. |

Terrorist Attacks of September 11, 2001: NATO in Afghanistan

The September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks on the United States were another pivotal moment in NATO's evolution. For the first and only time, the allies invoked NATO's Article 5 mutual defense clause and offered military assistance to the United States in responding to the attacks. Over the next 13 years, Canada and the European allies would join the United States to lead military operations in Afghanistan in what became by far the longest and most expansive operation in NATO history. As of March 2019, almost one-third of the fatalities suffered by coalition forces in Afghanistan have been from NATO members and partner countries other than the United States.9 In 2011, the high point of the NATO mission in Afghanistan, about 40,000 of the 130,000 troops deployed to the mission were from non-U.S. NATO countries and partners.10

Many analysts viewed the significant allied support of the United States following 9/11 as a powerful testament of NATO's enduring strength. The extent of European support could be considered especially remarkable given that many European publics were opposed to, or at best skeptical of, the war in Afghanistan and did not view the Taliban or Al Qaeda as imminent threats to Europe. Canada and the European allies also took on greater responsibilities in Afghanistan despite U.S. reluctance to involve NATO in initial military operations, and despite an acrimonious split between many European governments and the George W. Bush Administration over the U.S.-led war in Iraq. Many analysts point out that the United States only turned to NATO to take on a greater burden in Afghanistan after having launched military operations against Iraq in 2003. They argue that the United States would have been severely challenged to carry out both missions simultaneously without NATO support in Afghanistan.

Despite the unprecedented show of solidarity following the September 11 attacks, NATO operations in Afghanistan also exposed significant disparities in allied military capabilities and in allies' willingness to engage in combat operations. U.S. officials, including many Members of Congress, consistently criticized the European allies, and especially Germany, for shortfalls in capabilities and for national "caveats" that limited the scope of allied military engagement. The United States led a renewed push for the allies to increase defense spending and develop military capabilities to better respond to the new security environment, including "out-of-area" stabilization and counter-insurgency operations. The allies first adopted, albeit informally, the 2% of GDP defense spending guideline at NATO's 2006 summit in Prague.

Back to the Future: Russia's Annexation of Crimea and Renewed Deterrence

Russia's annexation of Crimea in 2014 and subsequent invasion of eastern Ukraine upended NATO's post-Cold War transformation into a more globally oriented security organization. Since 2014, the alliance has taken major steps to strengthen its territorial defense capabilities and deter Russia. NATO's renewed focus on collective defense and deterrence has created some tensions within the alliance, particularly between those member states that perceive Russia as an acute threat and those that favor engagement with Russia over confrontation. In addition, heightened fears about instability in the Middle East and North Africa have exposed differences between those allies more concerned about security threats from NATO's south and those that continue to prioritize deterring and managing Russia.

Reflecting the broadening security priorities of its member states, NATO has launched a range of initiatives, including a more robust military presence in its eastern member states and counterterrorism efforts in the Middle East and North Africa. NATO has established an Enhanced Forward Presence (EFP) of about 4,500 troops in the three Baltic States and Poland, increased military exercises and training activities in Central and Eastern Europe, and created new NATO command structures in six Central and Eastern European countries. As part of broader efforts to confront terrorist threats posed by instability in the Middle East and North Africa, NATO has launched a training mission in Iraq. The allies remain heavily invested in seeking to bring long-term stability to Afghanistan, including through a train-and-assist mission of about 17,000 (8,500 non-U.S.) soldiers. NATO continues to maintain a security force of 3,800 troops in Kosovo and also is seeking to develop more robust cyber defense capabilities and address the need to more effectively confront so-called hybrid warfare.

Most analysts agree, however, that while NATO has never been more engaged in such a broad range of security efforts, its activities continue to expose significant shortfalls, both in its deterrent posture and in broader crisis management efforts.

|

Key Outcomes of NATO's 2018 Brussels Summit Allied concerns about the U.S. commitment to NATO—and President Trump's criticisms of the alliance—were at the forefront of NATO's July 2018 summit in Brussels, Belgium. While NATO officials acknowledged "frank discussions on burdensharing," they stressed that President Trump joined the leaders of NATO's other 28 member states in endorsing a host of new initiatives aimed at strengthening NATO's deterrence of Russian aggression and bolstering its counterterrorism activities. These included the following new NATO initiatives:

Sources: NATO, "Press Conference by NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg at the Conclusion of the Brussels Summit," July 12, 2018, at https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/opinions_156738.htm; NATO, Brussels Summit Declaration, July 11-12, 2018, at https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/official_texts_156624.htm. For more on the pending accession of North Macedonia, see CRS Insight IN10977, Macedonia Changes Name, Moves Closer to NATO Membership, by Sarah E. Garding. |

The Burdensharing Debate

Since NATO's creation in 1949, the United States has been viewed as the unrivaled leader of the alliance. The United States continues to be the world's preeminent military power and U.S. defense spending long has been significantly higher than those of any other NATO ally. As early as the 1950s, however, U.S. political and military leaders—including some Members of Congress—expressed concern about European dependence on the U.S. security umbrella in Europe and the longer-term political and military implications of this dependence. To promote a more equitable sharing of the transatlantic security burden, Members of Congress and other U.S. leaders have focused most often on seeking to compel European allies to increase their national defense budgets in order to take on a greater share of the security burden. In the 1980s, for example, the U.S. Congress enacted legislation that would place a cap on U.S. force strength in Europe if the allies did not meet a target to grow national defense budgets annually by a rate of 3% higher than inflation.11

More recently, the allies have agreed to ensure that national defense budgets reach at least 2% of GDP by 2024 (discussed in more detail below). Analysts on both sides of the Atlantic have argued, however, that a relatively narrow focus on defense inputs (i.e., the size of defense budgets) could be wasted if not accompanied by an equal, if not greater, focus on defense outputs (i.e., military capabilities and the effectiveness of contributions to NATO missions and activities). The alliance's target to devote at least 20% of each member's national defense expenditure to new equipment and related research and development reflects this goal.

NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg also has emphasized a broader approach to measuring contributions to the alliance, using a metric of "cash, capabilities, and contributions." Others add that such a broader assessment of allied contributions would be more appropriate given NATO's wide-ranging strategic objectives, some of which may require capabilities beyond the military sphere.

Cash: National Defense Budgets, the 2% Guideline, and NATO's Common Fund

NATO members contribute financially to the alliance in various ways. The most fundamental way is by funding, in members' individual national defense budgets, the development of military capabilities that could support NATO missions and the deployment of their respective armed forces.

NATO member states also fund NATO's annual budget of about $2.6 billion by contributing to NATO's so-called "common funds." National contributions to the common funds pay for the day-to-day operations of NATO headquarters, as well as some collective NATO military assets and infrastructure. According to NATO, in 2018, the U.S. share of NATO's common-funded budgets was about 22%, or about $570 million, followed by Germany (15%), France (11%), and the United Kingdom (UK; 10%).12

In 2006, NATO members agreed informally to aim to spend at least 2% of gross domestic product (GDP) on national defense budgets annually and to devote at least 20% of national defense expenditure to procuring new equipment and related research and development. These targets were formalized at NATO's 2014 Wales Summit, when the allies pledged to "halt any decline in defence expenditure" and to "aim to move towards the 2% guideline within a decade."

The 2% and 20% spending targets are intended to guide national defense spending by individual NATO members; they do not refer to contributions made directly to NATO nor would all defense spending increases necessarily be devoted solely to meet NATO goals. For example, although the United States spends about 3.4% of GDP on defense, a relatively small portion of this spending goes to NATO and European security as the U.S. defense budget supports U.S. military engagements throughout the world.

Most analysts agree that the 2% spending figure "does not represent any type of critical threshold or 'tipping point' in terms of defense capabilities," and NATO does not impose sanctions on countries that fail to meet the target.13 However, the target is considered politically and symbolically important.

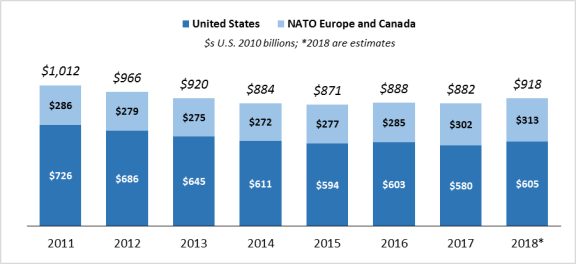

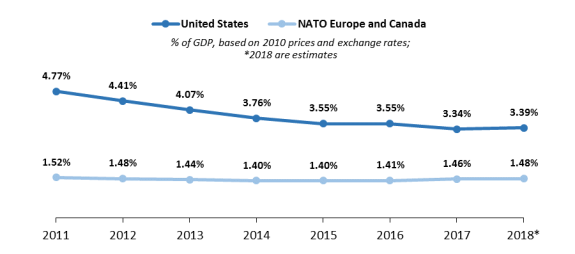

U.S. and NATO officials say they are encouraged by a steady rise in defense spending since the 2014 Wales Summit (See Figure 2). Whereas three allies met the 2% guideline in 2014, NATO estimates that seven allies met the target in 2018 (see Table A-1).14 Sixteen allies have submitted plans to meet the 2% and 20% targets by 2024.15 President Trump and others continue to criticize those NATO members perceived to be reluctant to achieve defense spending targets, however. This includes Europe's largest economy, Germany, which currently spends about 1.25% of GDP on defense and does not plan to reach 2% of GDP by 2024.

According to NATO defense spending figures, if every ally were to meet the 2% benchmark, the aggregate sum of NATO members' national defense budgets would increase by about $100 billion (from about $988 billion). Although most analysts agree that such an increase could benefit the alliance significantly, many stress that how additional resources are invested is equally, if not more, important. Critics note, for example, that an ally spending less than 2% of GDP on defense could have more modern, effective military capabilities than an ally that meets the 2% target but allocates most of that funding to personnel costs and relatively little to procurement and modernization.

|

Figure 2. Defense Spending by NATO Members, 2011-2018 The United States and NATO Europe and Canada |

|

|

Source: NATO, Defence Expenditure of NATO Countries, March 14, 2019. |

Capabilities: The 20% Guideline

NATO proponents point out that despite long-standing criticisms of European defense spending levels, the forces of key European allies still rank among the most capable militaries in the world; this assessment remains particularly true for the UK and France, which rank sixth and seventh, respectively in global defense expenditure (Germany ranks ninth).16 In 2018, total defense spending by European allies is expected to amount to about $282 billion (compared to about $685 billion for the United States), funding close to 1.8 million military personnel (compared to 1.3 million U.S. military personnel).17

Critics contend that defense spending in Europe is often inefficient, with disproportionately high personnel costs coming at the expense of much-needed research, development, and procurement and what they view as a considerable amount of duplication. They point to significant, long-standing shortfalls in key military capabilities, including strategic air- and sealift; air-to-air refueling; and intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR). NATO military planners also have sought to address so-called readiness shortfalls by urging allies to shorten the time it would take to mobilize and deploy forces. With respect to duplication, NATO officials lament that taken together, European countries have 17 different types of main battle tanks, 13 different types of air-to-air missiles, and 29 different types of naval frigates.18

In an effort to address these concerns, in 2014, the allies adopted the aforementioned guideline calling for 20% of member states' national defense budgets to be allocated to the procurement of new equipment and related research and development, considered to be a key indicator of the pace of military modernization. NATO leaders say they are encouraged by allied progress toward achieving this target: whereas four allies met the 20% target in 2013, 16 allies met the target in 2018 (see Table A-1).19

NATO officials have long sought to ensure that the national defense spending priorities of member states reflect the broader strategic priorities of the alliance. As these priorities have shifted, so too have its capabilities requirements. To this end, the alliance conducts a Defense Planning Process in order to harmonize national and NATO defense planning efforts to provide the required forces and capabilities in the most efficient way. These planning efforts also reflect the fact that among the NATO members only the United States, France, and the UK aspire to develop the full range of military capabilities necessary to maintain a global military footprint.

In light of this reality, NATO and U.S. leaders have promoted defense cooperation initiatives, including the pooling and sharing of national resources and joint acquisition of shared capabilities, aimed at stretching existing defense resources further. Analysts argue that the European defense industry remains fractured and compartmentalized along national lines; many believe that European defense efforts would benefit from a more cooperative consolidation of defense-industrial production and procurement as well as more transatlantic defense industrial cooperation. Progress on these fronts have been limited, however, with critics charging that national governments often remain more committed to protecting domestic constituencies than making substantive progress in joint capabilities development.20

Shifting strategic priorities present an additional challenge to long-term defense planning. In the two decades following the end of the Cold War, NATO defense planners promoted military modernization plans aimed at moving away from the large, heavily armored forces that were required for Cold War territorial defense to smaller, more agile forces that could be deployed across the globe. Some allies eliminated capabilities such as tanks (the Netherlands) and submarines (Denmark) that were thought to be outdated and unnecessary. Renewed concerns about Russian aggression have caused some analysts and policymakers to question those decisions, and have prompted reevaluations of capabilities targets in many European countries.

Contributions to NATO Missions

Allied contributions to NATO operations are another key factor often considered when assessing burdensharing dynamics in the alliance. Since the end of the Cold War, NATO allies and partner countries have contributed to a range of NATO-led military operations across the globe, including in the Western Balkans, Afghanistan, the Mediterranean Sea, the Middle East, and Eastern Europe. Many in Europe and Canada view their contributions to NATO operations in Afghanistan as an unparalleled demonstration of solidarity with the United States and a testament to the value they can provide in achieving shared security objectives. Some analysts also point out that to meet the costs of maintaining continuous deployments to Afghanistan, many member states delayed needed defense modernization efforts. Ongoing contributions often cited by European allies include the following:

- Afghanistan. More than 100,000 troops from Canada and European NATO members have served in the country since 2001, when U.S.-led military operations commenced. At the height of NATO-led operations in the country, over 40,000 non-U.S. allies and partner country personnel were deployed to the mission. As of March 2019, Canada and the European allies had suffered approximately 1,050 of the 3,561 of coalition fatalities suffered in Afghanistan.21

Since 2007, non-U.S. allies and NATO partners have committed more than $2.6 billion to the Afghan National Army Trust Fund. As of February 2019, approximately 8,500 of the 17,000 troops deployed to NATO's follow-on train-and-assist mission in Afghanistan are from European NATO member states or NATO partner countries (including 1,300 from Germany, 1,100 from the UK, and 895 from Italy).22 - NATO deterrence and collective defense efforts. Since 2014, European allies and Canada have contributed forces and capabilities to bolster deterrence and collective defense initiatives. This includes leading three of the four battlegroups of NATO's Enhanced Forward Presence in Poland and the Baltic States, commanding NATO's Baltic Air Policing Mission, contributing to NATO's standing naval forces in the Baltic and Black Seas, AWACS patrols over Eastern Europe, command of the NATO Response Force and Very High Readiness Joint Task Force, and hosting new NATO command and control facilities in Central and Eastern Europe.

- Kosovo. Since 1999, tens of thousands of non-U.S. allies have contributed to NATO's Kosovo Force (KFOR) to maintain security and stability in Kosovo. As of February 2019, non-U.S. allies and NATO partner countries contributed about 3,000 of the 3,500 KFOR troops.23

NATO operations also have exposed significant disparities in allied military capabilities, especially between the United States and the other allies. In most, if not all, NATO military interventions, European allies and Canada have depended on the United States to provide key capabilities such as air- and sea-lift, refueling, and ISR. In some cases, the United States has filled more basic shortfalls, in munitions for example.

NATO's 2011 military intervention in Libya, Operation Unified Protector (OUP), highlighted these shortfalls. Although OUP was the first NATO mission in which the United States did not lead military operations, the six allies carrying out NATO airstrikes—Belgium, Canada, Denmark, France, Norway, and the UK—faced munition and other shortfalls relatively early on. Then-Secretary of Defense Robert Gates encapsulated U.S. frustration when he stated, "the mightiest military alliance in history is only 11 weeks into an operation against a poorly armed regime in a sparsely populated country – yet many allies are beginning to run short of munitions, requiring the U.S., once more, to make up the difference."24

Managing Relations with Russia

Russia's annexation of Crimea and subsequent invasion of Eastern Ukraine in 2014 prompted a sweeping reassessment of NATO's post-Cold War efforts to build a cooperative relationship with Moscow. In the words of then-NATO Deputy Secretary General Alexander Vershbow, "For 20 years, the security of the Euro-Atlantic region has been based on the premise that we do not face an adversary to our east. That premise is now in doubt."25 Since 2014, Russia also has increased its military activities in northern Europe, particularly through reportedly deploying nuclear-capable missiles to Kaliningrad, enhancing its air patrolling activities close to allied airspace, and increasing its naval presence in the Baltic Sea, the Arctic Ocean, and the North Sea.26

In response to Russian aggression in Ukraine, NATO has moved to implement what its leadership characterized as the greatest reinforcement of NATO's collective defense since the end of the Cold War.27 Although the allies have continued to support and contribute to NATO deterrence initiatives, some express concern about the effectiveness and sustainability of these efforts. Many analysts, including the authors of a February 2016 report by the RAND Corporation, contend that "as presently postured, NATO cannot successfully defend the territory of its most exposed members."28 Some allies, including Poland and the Baltic States, have urged a more robust allied military presence in the region to "make it plain that crossing NATO's borders is not an option."29

Others, including leaders in Western European countries like Germany and Italy, have stressed the importance of a dual-track approach to Russia that complements deterrence with dialogue. For these allies, efforts to rebuild cooperative relations with Moscow may be given as much attention as efforts to deter Russia. Accordingly, NATO continues to resist calls to permanently deploy troops in countries that joined after the collapse of the Soviet Union due to concerns in these member states that this would violate the terms of the 1997 NATO-Russia Founding Act; NATO's Enhanced Forward Presence has been referred to as "continuous," but rotational.30 Former German Foreign Minister (and current German President) Frank-Walter Steinmeier encapsulated concerns about NATO's deterrence posture in 2016 when he likened a military exercise of NATO member states and partner countries taking place in Poland to "saber-rattling and war cries."31 He added, "whoever believes that a symbolic tank parade on the alliance's eastern border will bring security, is mistaken."32 NATO and U.S. officials subsequently rebutted Steinmeier's comments.

Discussions over NATO's strategic posture could continue to be marked by these divergent views over the threat posed by Russia and by debate over the appropriate role for NATO in addressing the wide-ranging security challenges emanating from the Middle East and North Africa (MENA). On threats from the MENA region, several allies are reluctant to endorse a bigger role for NATO in issues—such as terrorism and migration—on which the European Union (EU) has traditionally taken the lead. Furthermore, many analysts contend that significant budgetary and political constraints facing many allied governments could limit NATO's capacity to deter Russia while addressing security threats to NATO's south.

U.S. Policy: Shifting U.S. Priorities and the Benefits and Costs of NATO Membership

Since NATO's founding, successive U.S. Administrations have viewed U.S. membership in, and leadership of, NATO as a key pillar of U.S. national security strategy. As outlined above, throughout NATO's evolution, U.S. leadership has given the United States a strong voice in formulating strategic objectives for NATO that align with U.S. national security objectives. U.S. military objectives in Europe also have shifted over time, especially since the end of the Cold War. Today, about 74,000 U.S. military service members, including two Brigade Combat Teams (BCTs), are stationed in Europe, compared to more than 400,000 troops at the height of the Cold War.

Throughout the 1990s and 2000s, United States European Command (EUCOM) shifted its activities in Europe to non-warfighting missions, including building defense capacity and capability in former Warsaw Pact states and logistically supporting other U.S. combatant commands. Events in recent years, particularly Russia's actions in Ukraine since 2014 and increased military activities near NATO borders, have tested the strategic assumptions underpinning EUCOM's posture.

While President Trump has criticized NATO, his Administration's National Security Strategy and National Defense Strategy both identify European security and stability as key U.S. national security interests and emphasize the U.S. commitment to NATO and Article 5. Administration officials and many Members of Congress underscore that the Administration has requested significant increases in funding for U.S. military deployments in Europe under the European Deterrence Initiative (EDI, previously known as the European Reassurance Initiative, or ERI).33

Proponents of NATO argue that U.S. membership in and leadership of NATO brings a range of important benefits to the United States. These include, but are not limited to, the following:

- Peace, stability, conflict prevention, and deterrence. Many analysts believe that NATO has played a vital role in keeping the peace in Europe for the last 70 years and preventing a repeat of the two World Wars of the first half of the 20th century. NATO proponents add that a divided NATO with a less committed United States could benefit Russia's widely acknowledged efforts to undermine NATO and the EU.

- Treaty-based defense and security support from 28 allies, including many of the world's most advanced militaries, including a nuclear deterrent and missile defense systems based in Europe. Despite the criticisms of European defense spending trends, non-U.S. allies still possess significant military capabilities, which they have deployed in support of U.S. security objectives.

- An unrivaled platform for constructing and operating international military coalitions. Through its history, NATO has developed an integrated command structure to carry out collective defense and crisis management operations that is unprecedented in terms of size, scale, and complexity. This includes advancing allied interoperability by designing command and control systems, holding multinational training exercises, and creating policies for standardizing equipment amongst its members.

- U.S. military bases in strategically important locations. U.S. leadership of NATO has allowed the United States to station U.S. forces in Europe at bases that enable quicker air, sea, and land access to other locations of strategic importance, including the Middle East and Africa.

- Economic stability. The EU, which includes 22 NATO allies, is the United States' largest trade and investment partner. By promoting security and stability in Europe, NATO helps protect this extensive economic relationship that accounts for 46% of global GDP.34

Nevertheless, questions about the value of NATO to the United States have led some to reassess the benefits and costs of U.S. membership. Critics of NATO highlight a number of costs incurred by the United States—both qualitative and quantitative—due to its leadership of NATO. These include the following:

- Loss of autonomy. Whether at the strategic or the operational level, forging agreement with 28 other governments is undoubtedly more difficult than maintaining full national control. Analysts note, for example, that U.S. military planners' negative experience working with European counterparts during the NATO intervention in Kosovo in 1999 (European allies' reportedly rejected bombing targets proposed by U.S. commanders) was a key factor behind the U.S. decision to conduct initial military operations in Afghanistan outside the NATO command structure.35 Some have argued that ad hoc coalitions of like-minded allies under unified U.S. command could be more desirable than working within established NATO structures.

- Heightened risks to U.S. forces. Some critics argue that the Article 5 commitment to defend a NATO ally in the event of an attack could draw the United States into a conflict that it might otherwise avoid. Others note that Article 5 commits an ally to respond to an attack by "taking such action as it deems necessary."

- Continued European dependence. Some critics contend that European allies' dependence on the U.S. security guarantee limits their incentive to invest in defense capabilities that would make them more capable partners for the United States. At the same time, President Trump's criticisms of NATO and individual allies have caused some in Europe to question the United States' continued reliance as a security partner.36

- Provoking Russia. Some critics of NATO argue that NATO's post-Cold War enlargement to include former members of the Warsaw Pact and the Baltic states represented an unnecessary and counter-productive provocation of Russia and ensured long-term rivalry between Russia and "the West."

- A negative budgetary impact. U.S membership in NATO carries with it certain financial commitments, including annual contributions to NATO's Common Fund (about $570 million in 2018). The U.S. missile defense capability in Europe is also under NATO command, and the United States contributes an estimated $800 million annually to additional NATO capabilities such as Allied Ground Surveillance and strategic airlift.37

Although the United States could potentially reduce its military footprint in Europe, analysts point out that without a reduction in overall U.S. force structure, the Department of Defense would still cover the costs of redeployed personnel. Additionally, as noted above, U.S. military bases in Europe offer strategic and logistical advantages beyond enabling U.S. commitments to NATO.

|

Cost Assessments of the U.S. Military Footprint in Europe Calculating how much the U.S. spends to maintain a force presence in Europe is complicated in part by limited budget data, varying cost estimates, reimbursements from tenant organizations, and other factors. For FY2019, the Department of Defense (DOD) estimated "the amounts necessary for payment of" personnel, operations, maintenance, facilities, and support costs for its military units in Europe and the costs of supporting dependents who accompany DOD personnel to Europe at $10.4 billion. However, this figure does not include "incremental costs associated with contingency operations" or investments in deployed military capabilities, such as funding for procurement or research, development, test, and evaluation programs. Among the costs not included in the $10.4 billion figure are expenditures for the European Deterrence Initiative (about $6.5 billion in the FY2019 Overseas Contingency Operations budget) and the costs of maintaining key U.S. military capabilities in Europe such as missile defense. The Government Accountability Office (GAO) has published multiple reports on the U.S. force structure in Europe that include cost estimates for certain activities, as have various nongovernmental organizations:

Notes: This section was written by Brendan McGarry, Analyst in U.S. Defense Budget. Sources: Department of Defense, Operations and Maintenance Overview Fiscal Year 2019 Budget Estimates, March 2018, "Overseas Cost Summary" p. 203 at https://comptroller.defense.gov/Portals/45/Documents/defbudget/fy2019/fy2019_OM_Overview.pdf#page=206; United States Government Accountability Office, DEFENSE MANAGEMENT: Additional Cost Information and Stakeholder Input Needed to Assess Military Posture in Europe, February 2011, at https://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-11-131; United States Government Accountability Office, Defense Planning: DOD Needs to Review the Costs and Benefits of Basing Alternatives for Army Forces in Europe, September 13, 2010, at https://www.gao.gov/assets/100/97056.pdf; Lucie Beraud-Sudreau and Nick Childs, The U.S. and its NATO Allies: Costs and Value, International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS), July 9, 2018. |

Considerations for Congress

Congress was instrumental in creating NATO in 1949 and has played a critical role in shaping U.S. policy toward the alliance ever since. While many Members of Congress have criticized specific developments within NATO—regarding burdensharing, for example—Congress as a whole has consistently demonstrated strong bipartisan support for active U.S. leadership of and support for NATO. This support has manifested itself through an array of congressional action including financial support through the authorization and appropriations processes and legislation enabling NATO enlargement and NATO military operations and deterrence efforts. Congress also has been at the forefront of the burdensharing debate within NATO since the alliance's inception and has often called on U.S. Administrations to do more to secure increased allied commitments to NATO.

Congressional support for NATO has traditionally served to buttress broader U.S. policy toward the alliance. During the Trump Administration, however, demonstrations of congressional support for NATO have at times been viewed more as an effort to reassure allies about the U.S. commitment to NATO after President Trump's criticisms of the alliance. Trump Administration officials stress that the Administration remains strongly committed to NATO and to European security (as articulated in the National Security and Defense strategies), and Congress has supported the Administration's requests to increase funding for key U.S. defense activities in Europe such as the European Deterrence Initiative.

Nevertheless, during the Trump Administration both chambers of Congress have passed legislation expressly reaffirming U.S. support for NATO at times when some allies have questioned the President's commitment. This includes legislation passed by the House in January 2019 (H.R. 676, see below) seeking to limit the president's ability to unilaterally withdraw from NATO; similar legislation has been introduced in the Senate (S.J.Res. 4). Some analysts portrayed House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell's joint invitation to NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg to address a joint session of Congress on April 3, 2019, in commemoration of NATO's 70th anniversary as an additional demonstration of NATO's importance to the Congress. Examples of legislation in support of NATO passed in Congress since 2017 include the following:

- H.Res. 397 (115th Congress), Solemnly reaffirming the commitment of the United States to NATO's principle of collective defense as enumerated in Article 5 of the North Atlantic Treaty. Passed by the House by a vote of 423-4 on June 27, 2017.

- H.R. 5515/P.L. 115-232 (115th Congress), John S. McCain National Defense Authorization Act for FY2019. After the Senate agreed to go to conference with the House on H.R. 5515, Senator Reed (RI) made a motion to instruct conferees to reaffirm the commitment of the United States to NATO. The Senate agreed to the motion by a vote of 97-2.

- H.Res. 256 (115th Congress), Expressing support for NATO and the countries of Central and Eastern Europe. Passed by the House by unanimous consent on July 11, 2018.

- H.R. 676 (116th Congress), NATO Support Act. Passed by the House by a vote of 357-22 on January 22, 2019. The bill prohibits the appropriation or use of funds to withdraw the United States from NATO.

Although Congress has expressed consistent bipartisan support for NATO and its cornerstone Article 5 mutual defense commitment, congressional hearings on NATO in the 115th and 116th Congresses have reflected disagreement on the impact President Trump is having on the alliance.38 Some in Congress argue that President Trump's criticism of allied defense spending levels has spurred recent defense spending increases by NATO members that were not forthcoming under prior Administrations despite long-standing U.S. concern. They point out that NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg has acknowledged that President Trump "is having an impact" in securing $41 billion of additional defense spending by European allies and Canada since 2016.39

Others in Congress counter that President Trump's admonition of U.S. allies and his questioning of NATO's utility has damaged essential relationships and undermined NATO's credibility and cohesion. They contend that doubts about the U.S. commitment to NATO could embolden adversaries, including Russia, and ultimately weaken the commitment of other allies to the alliance. Some analysts argue that European allies who feel belittled by the U.S. president might be less likely to support future NATO operations advocated by the United States. Critics also tend to downplay President Trump's role in securing recent defense spending increases by NATO allies. They argue that Russian aggression in Europe has been a greater factor behind rising defense budgets, particularly in Central and Eastern Europe.

Despite disagreement over President Trump's impact on the alliance, most Members of Congress continue to express support for robust U.S. leadership of NATO, in particular to address potential threats posed by Russia. Many Members have called for enhanced NATO and U.S. military responses to Russian aggression in Ukraine and others have advocated stronger European contributions to collective defense measures in Europe. Congressional consideration of EDI could enable further examination of U.S. force posture in Europe and the U.S. capacity and willingness to uphold its collective defense commitments. Deliberations could also highlight longer-standing concerns about European contributions to NATO security and defense measures.

In light of these considerations, Members of Congress could focus on several key questions regarding NATO's future. These might include the following:

- addressing the strategic value of NATO to the United States and the leadership role of the United States within NATO;

- examining whether the alliance should adopt a new strategic concept that better reflects views of the security threat posed by Russia and new and emerging threats in the cyber and hybrid warfare domains (NATO's current strategic concept was adopted in 2010);

- examining NATO's capacity and willingness to address other security threats to the Euro-Atlantic region, including from the Middle East and North Africa, posed by challenges such as terrorism and migration;

- examining the possible consequences of member states' failure to meet agreed defense spending targets;

- assessing U.S. force posture in Europe and the willingness of European allies to contribute to NATO deterrence efforts and U.S. defense initiatives in Europe such as the ballistic missile defense program and EDI;

- revisiting the allies' commitment to NATO's stated "open door" policy on enlargement, especially with respect to the membership aspirations of Georgia and Ukraine; and

- developing a NATO strategy toward China, particularly given U.S. and other allies' concerns about the security ramifications of increased Chinese investment in Europe.

Appendix. Additional Defense Spending Information

|

Figure A-1. Defense Spending by NATO Members as a % of GDP 2011-2018 United States and NATO Europe and Canada |

|

|

Source: NATO, Defence Expenditure of NATO Countries, March 14, 2019. |

|

% of GDP on Defense Spending |

% of Defense Spending on Equipment (20% goal) |

|||||||||||||||||

|

NATO Members |

2014 |

2018e |

% Change |

2014 |

2018e |

% Change |

||||||||||||

|

NATO Europe |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Albania |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Belgium |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Bulgaria |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Croatia |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Czech Republic |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Denmark |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Estonia |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

France |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Germany |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Greece |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Hungary |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Italy |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Latvia |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Lithuania |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Luxembourg |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Montenegro |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Netherlands |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Norway |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Poland |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Portugal |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Romania |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Slovak Republic |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Slovenia |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Spain |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Turkey |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

United Kingdom |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

North America |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Canada |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

United States |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

NATO Total |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||