Cyclone Idai

Source: EUMETSAT.

On March 14, a large and powerful tropical storm dubbed Cyclone Idai came ashore at Beira, a low-lying port city in central Mozambique, in southeastern Africa. It featured sustained winds as high as 120 miles per hour prior to making landfall and dumped torrents of rain over large parts of Mozambique, Malawi, Zimbabwe, and Madagascar. Its effects have been expansive and catastrophic—covering at least 1,200 square miles—and it is among the worst natural disasters ever to hit the region. Flooding has limited humanitarian response organizations' access to much of the affected region.

|

Cyclone Idai |

|

|

Source: EUMETSAT. |

As of March 21, the cyclone had reportedly caused at least 550 deaths—259 in Zimbabwe, 242 in Mozambique, and 56 in Malawi— and casualties may rise sharply. Regionally 2.6 million people have been impacted, including at least 400,000 persons in Mozambique. It also has displaced more than 922,900 persons in Malawi (which was stricken by the storm before it went offshore and then returned with renewed power) and 50,000 Zimbabwean households.

Intense winds caused widespread damage to private housing and public infrastructure—notably hospitals and electrical, road, and bridge systems—hindering post-storm access to education and health care facilities and disrupting economic activity. Up to 90% of Beira's housing and infrastructure was severely damaged. This could have regional effects, as Beira and transport links leading inland are key channels for goods bound for land-locked Zimbabwe and Malawi. Crops have also suffered widespread damage—a perilous outcome in a region where local communities rely on subsistence farming. As many as 85,000 hectares were flooded prior to the cyclone.

|

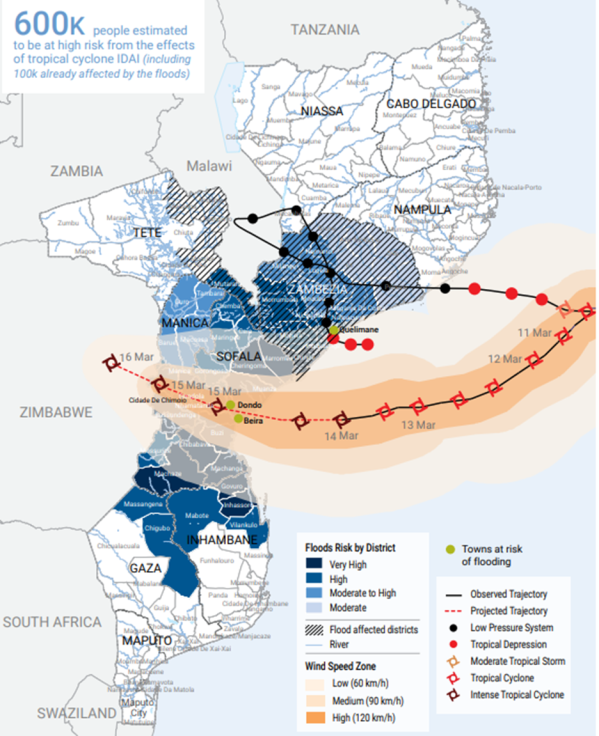

Figure 1. Cyclone Idai: Track and Affected Region |

|

|

Source: Pacific Disaster Center/U.N. Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. Note: Boundaries, names, designations used on map do not imply U.N. or other official endorsement. |

Cyclonic rainfall produced extensive flooding and associated water damage—notably mudslides and powerful riverine flash flooding—in Mozambique, eastern Zimbabwe, and southern Malawi, both due to its volume and as it fell on already-saturated ground. Flooding has contaminated local water sources, raising fears of water-borne disease outbreaks. Access to improved sanitation and clean water is low in the affected region, where outbreaks of diseases like cholera occur regularly. Rates of malaria, an endemic disease, could also spike as water pools, creating a breeding ground for mosquitoes.

National and international public agencies and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) have launched a multi-faceted humanitarian response. Initially centered on emergency rescues, assessments of impact and need, and establishment of logistical operations, the response is transitioning toward deliveries of food, shelter, and other aid. Response operations are currently based at Beira's airport, which has facilitated coordination among the many responding actors but raised concerns regarding possible flight and aid delivery congestion and warehouse limitations.

Initial funding pledges or allocations include $20 million in U.N. emergency funds, £20 million from the UK government, and €3.5 million from the European Commission. Funding is allocated to countries, the region, or functional responses. The U.N. Resident Coordinator for Mozambique has launched a $40.8 million initial appeal in support of a range of immediate response activities. Subsequent needs, especially for rebuilding, are likely to be substantial.

|

Mozambique: General Background Mozambique is nearly twice as large as California. Once a one-party, socialist state, it successfully developed a multi-party democracy and a market-based economy after a post-independence civil war (1976-1992). It has rich agricultural and mineral resources, and is developing vast offshore natural gas reserves in the far north, but poverty is widespread (GDP in 2018 was $481 per capita). Foreign investment has been oriented toward large industrial projects often favoring political elites. Rapid post-war growth has slowed in recent years, but the International Monetary Fund (IMF) projects a sharp rise in 2023 or later, once gas exports begin. Corruption is a long-standing problem. The government is struggling to manage a $2 billion scandal involving opaque state-guaranteed loans that were not reported to the IMF. The matter is the focus of U.S. and Mozambican prosecutions. Beginning in 2012, resurgent tension between the former civil war foes, the opposition RENAMO party and the FRELIMO party-led government, spurred periodic armed clashes over several years. Lengthy negotiations led to accords in 2018, which appear to have largely addressed RENAMO's grievances, which sparked the conflict, though further instability is possible. A separate conflict emerged in late 2017, when an enigmatic, violent Islamist extremist group initiated periodic attacks on local villages and state targets (e.g., police) that have included beheadings and widespread arson. These attacks have continued, resulting in nearly 100 deaths, despite government counter-insurgency efforts. The group is active in a small, isolated region on the northern coast, limiting the impact on communities but posing a threat to nearby gas development activities. U.S. Assistance. U.S. contributions to the cyclone emergency response in Mozambique supplement diverse nonemergency U.S. assistance totaling $472 million in FY2018, with $403 million requested for FY2020. In recent years, such assistance has focused primarily on health care and programs to address a high HIV prevalence rate (12.5% among adults in 2017). Other recent-year priorities have included programs to improve the basic education and justice systems, provide youth job training, train media to counter extremist propaganda, and enhance military capabilities. |

Congress may closely monitor the U.S. and international response as the relief effort progresses. The U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) is providing an initial $700,000 to support critical needs in Mozambique, Zimbabwe, and Malawi, with a focus on water, sanitation, hygiene, and shelter. It has deployed a small assessment team to Mozambique, with a focus on Beira. A further $3.4 million in U.S. food and other aid commodities is being dispatched to the region.

On March 20, USAID's Office of U.S. Foreign Disaster Assistance activated a Disaster Assistance Response Team (DART) and a U.S.-based Response Management Team. The DART is continuing to deploy to Mozambique. It is to focus on scaling up U.S. assessments, identifying priority needs, and coordinating assistance responses.

The Department of Defense (DOD) has provided an aircraft to aid DART assessments and may provide further logistical support if requested. USAID and U.S. Africa Command are closely communicating regarding such issues and the evolving response.