Source: CRS, BBC News.

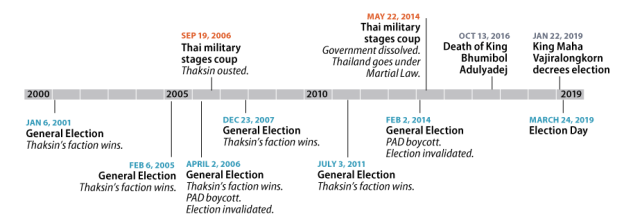

Nearly five years after the Royal Thai Army seized power in a coup d'état in 2014, the Kingdom of Thailand is officially set to hold nationwide parliamentary elections on March 24, 2019 (see Figure 1).

While the announcement comes as welcome news to many Thais, new elections may reignite political tensions and uncertainties that have been suppressed for the last four years under military rule. Thailand, a U.S. treaty ally, had emerged from the upheaval of the 1998 Asian Financial Crisis with a strongly democratic constitution and newly independent national institutions. However, political tensions between competing forces including the military, the monarchy, and a populist politician have exposed the weakness of the country's democratic institutions, resulting in a series of weak governments paralyzed by street demonstrations around Bangkok and ultimately overthrown by military coups in 2006 and 2014 that have shaken the bilateral alliance with the United States.

On May 22, 2014, Thailand's military junta, formally known as the National Council for Peace and Order (NCPO), responded to months of street protests in Bangkok and political controversy over the conduct of elections by overthrowing the newly elected government, abrogating the constitution, and imposing martial law. The junta subsequently oversaw the rewriting of Thailand's Constitution in ways that protect the military's control over parliament in upcoming elections.

Thailand is no stranger to political upheaval and civil unrest. Since becoming a constitutional monarchy in 1932, the kingdom has held 25 general elections and experienced 19 coups, 12 of which were successful.

Despite the kingdom's numerous coups over the decades, Thailand's long-ruling king, Bhumibol Adulyadej, was a stabilizing force and symbol of common unity for the Thai people. The 2016 death of King Bhumibol caused more uncertainty surrounding the country's political stability. The late king's son, King Maha Vajiralongkorn, is widely unpopular, and has spent much of his life away from politics and out of the country, making him somewhat of a political wildcard. The new king's approval of the junta-backed constitution, however, indicates that his political leanings favor the military, which has traditionally been considered the protector of the throne.

|

|

Source: CRS, BBC News. |

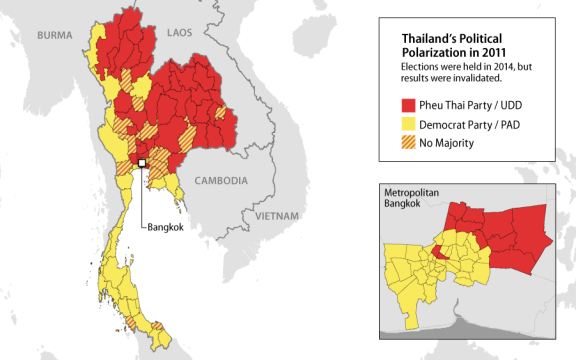

Former Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra, a divisive figure who was deposed in the 2006 coup, is the catalyst for much of the political turmoil surrounding Thailand's elections over the last two decades. Upon entering politics in 1998, Thaksin quickly built a formidable political machine by appealing to Thailand's traditionally overlooked lower-class, rural voters by connecting with them directly, offering policies such as low-cost health care, education equality, and agricultural programs (see Figure 2). As a result, Thaksin won landslide victories in 2001 and 2005, and a third victory in 2006 in elections that were boycotted by the opposition.

Thaksin's policies and his moves to seek influence with both the military and the Royal palace were widely criticized by Thailand's urban elites, who viewed his method of governance as not only controversial and corrupt, but also as the catalyst for corroding Thailand's traditional hierarchical power structure. Nevertheless, Thaksin-loyalist parties have won three more general elections since his ouster, although successive prime ministers have been ousted on corruption and other charges—which some supporters say have been politically motivated.

The People's Alliance for Democracy (PAD), or "Yellow Shirts" movement, was founded as a political pressure group opposed to Thaksin's growing power immediately following his second landslide victory in 2005. Thaksin was ousted in a coup d'état following a snap election in 2006, in which his party also won. Thaksin's ousting sparked a firestorm of anger amongst his supporters. The pro-Thaksin United Front for Democracy Against Dictatorship (UDD), or "Red Shirts" movement, was formed as an opposition force to the PAD in 2006. The long-standing feud between the two factions has resulted in violent clashes with each other and Thailand's security forces over the years and contributed to the Thai Army's decision to overthrow the UDD-supported government in the 2014 coup.

|

"RED" AND "YELLOW" POLITICS |

|

|

The United Front for Democracy Against Dictatorship |

The People's Alliance for Democracy |

|

Red Shirts |

Yellow Shirts |

|

Rural, Lower Class |

Urban, Middle / Elite Classes |

|

"Thaksin-Loyalist" Faction |

"Anti-Thaksin" Faction |

|

Pro-Democracy |

Pro-Monarchy |

|

|

Source: CRS, Election Commission of Thailand. Notes: 2011 is the most recent election data available. |

The Role of the Military in the Electoral Process.

A candidate needs 376 votes in parliament to become prime minister, but amendments made to Thailand's constitution in 2017, drafted by the junta, gave the military sole authority to handpick each of the 250 senators in Thailand's Upper House of Parliament. Thai nationals will only be voting for the 500 members in Parliament's Lower House, the House of Representatives, which means an opposition victory would have to be overwhelming to succeed. Many observers believe that the amended constitution was created to serve as an "insurance policy" for the junta to retain power regardless of the election's outcome.

A Military-Backed Prime Minister and the Possibility of Violence.

Given Thailand's history of violence after elections, many experts are uneasy about the potential for unrest and the potential for history repeating itself. The prospect of a military prime minister (most likely current junta prime Minister Prayuth Chan-ocha) being appointed following polls in which majorities vote for UDD candidates reignites fears of protests occurring in the election's aftermath.

Impact on U.S.-Thai Bilateral Relations

Congress may consider what the newly elected parliament and government will herald for U.S.-Thai relations, which have been hampered by the two coups. Although a return to a government chosen, at least in part, through elections may remove uncertainties about U.S. security assistance, continued divisiveness in Thai politics would signal that political instability persists. A peaceful election may be the first of many necessary steps towards mending the bilateral relationship back to its pre-coup status.