Introduction

This report provides background information and potential oversight issues for Congress on the Coast Guard's programs for procuring 8 National Security Cutters (NSCs), 25 Offshore Patrol Cutters (OPCs), and 58 Fast Response Cutters (FRCs). The Coast Guard's proposed FY2019 budget requested a total of $705 million in acquisition funding for the NSC, OPC, and FRC programs.

The issue for Congress is whether to approve, reject, or modify the Coast Guard's funding requests and acquisition strategies for the NSC, OPC, and FRC programs. Congress's decisions on these three programs could substantially affect Coast Guard capabilities and funding requirements, and the U.S. shipbuilding industrial base.

The NSC, OPC, and FRC programs have been subjects of congressional oversight for several years, and were previously covered in an earlier CRS report that is now archived.1 CRS testified on the Coast Guard's cutter acquisition programs most recently on July 25, 2017.2 The Coast Guard's plans for modernizing its fleet of polar icebreakers are covered in a separate CRS report.3

Background

Older Ships to Be Replaced by NSCs, OPCs, and FRCs

The 91 planned NSCs, OPCs, and FRCs are intended to replace 90 older Coast Guard ships—12 high-endurance cutters (WHECs), 29 medium-endurance cutters (WMECs), and 49 110-foot patrol craft (WPBs).4 The Coast Guard's 12 Hamilton (WHEC-715) class high-endurance cutters entered service between 1967 and 1972.5 The Coast Guard's 29 medium-endurance cutters include 13 Famous (WMEC-901) class ships that entered service between 1983 and 1991,6 14 Reliance (WMEC-615) class ships that entered service between 1964 and 1969,7 and 2 one-of-a-kind cutters that originally entered service with the Navy in 1944 and 1971 and were later transferred to the Coast Guard.8 The Coast Guard's 49 110-foot Island (WPB-1301) class patrol boats entered service between 1986 and 1992.9

Many of these 90 ships are manpower-intensive and increasingly expensive to maintain, and have features that in some cases are not optimal for performing their assigned missions. Some of them have already been removed from Coast Guard service: eight of the Island-class patrol boats were removed from service in 2007 following an unsuccessful effort to modernize and lengthen them to 123 feet; the one-of-a-kind cutter that originally entered service with the Navy in 1944 was decommissioned in 2011; and the Hamilton-class cutters are being decommissioned as new NSCs enter service. A July 2012 Government Accountability Office (GAO) report discusses the generally poor physical condition and declining operational capacity of the Coast Guard's older high-endurance cutters, medium-endurance cutters, and 110-foot patrol craft.10

Missions of NSCs, OPCs, and FRCs

NSCs, OPCs, and FRCs, like the ships they are intended to replace, are to be multimission ships for routinely performing 7 of the Coast Guard's 11 statutory missions, including

- search and rescue (SAR);

- drug interdiction;

- migrant interdiction;

- ports, waterways, and coastal security (PWCS);

- protection of living marine resources;

- other/general law enforcement; and

- defense readiness operations.11

Smaller Coast Guard patrol craft and boats contribute to the performance of some of these seven missions close to shore. NSCs, OPCs, and FRCs perform them both close to shore and in the deepwater environment, which generally refers to waters more than 50 miles from shore.

NSC Program

National Security Cutters (Figure 1)—also known as Legend (WMSL-750)12 class cutters because they are being named for legendary Coast Guard personnel13—are the Coast Guard's largest and most capable general-purpose cutters.14 They are larger and technologically more advanced than Hamilton-class cutters, and are built by Huntington Ingalls Industries' Ingalls Shipbuilding of Pascagoula, MS (HII/Ingalls).

|

|

Source: U.S. Coast Guard photo accessed May 2, 2012, at http://www.flickr.com/photos/coast_guard/5617034780/sizes/l/in/set-72157629650794895/. |

The Coast Guard's acquisition program of record (POR)—the service's list, established in 2004, of planned procurement quantities for various new types of ships and aircraft—calls for procuring 8 NSCs as replacements for the service's 12 Hamilton-class high-endurance cutters. The Coast Guard's FY2019 budget submission estimated the total acquisition cost of a nine-ship NSC program at $6.030 billion, or an average of about $670 million per ship.15

Although the Coast Guard's POR calls for procuring a total of 8 NSCs to replace the 12 Hamilton-class cutters, Congress through FY2018 has funded 11 NSCs, including two (the 10th and 11th) in FY2018. Six NSCs are now in service (the sixth was commissioned into service on April 1, 2017). The seventh is scheduled to be commissioned into service in January 2019, and the eighth and ninth are scheduled for delivery in 2019 and 2020, respectively. The Coast Guard's proposed FY2019 budget requested $65 million in acquisition funding for the NSC program; this request does not include additional funding for a 12th NSC.

For additional information on the status and execution of the NSC program from a May 2018 GAO report, see Appendix C.

OPC Program

Offshore Patrol Cutters (Figure 2, Figure 3, and Figure 4)—also known as Heritage (WMSM-915)16 class cutters because they are being named for past cutters that played a significant role in the history of the Coast Guard and the Coast Guard's predecessor organizations17—are to be somewhat smaller and less expensive than NSCs, and in some respects less capable than NSCs.18 In terms of full load displacement, OPCs are to be about 80% as large as NSCs.19 Coast Guard officials describe the OPC program as the service's top acquisition priority. OPCs are being built by Eastern Shipbuilding Group of Panama City, FL.

|

Figure 2. Offshore Patrol Cutter Artist's rendering |

|

|

Source: "Offshore Patrol Cutter Notional Design Characteristics and Performance," accessed September 16, 2016, at https://www.dcms.uscg.mil/Portals/10/CG-9/Surface/OPC/OPC%20Placemat%2036x24.pdf?ver=2018-10-02-134225-297. |

|

Figure 3. Offshore Patrol Cutter Artist's rendering |

|

|

Source: "Offshore Patrol Cutter Notional Design Characteristics and Performance," accessed September 16, 2016, at https://www.dcms.uscg.mil/Portals/10/CG-9/Surface/OPC/OPC%20Placemat%2036x24.pdf?ver=2018-10-02-134225-297. |

The Coast Guard's POR calls for procuring 25 OPCs as replacements for the service's 29 medium-endurance cutters. The Coast Guard's FY2019 budget submission estimated the total acquisition cost of the 25 ships at $10.523 billion, or an average of about $421 million per ship.20 The first OPC was funded in FY2018 and is to be delivered in 2021. The Coast Guard's proposed FY2019 budget requested $400 million in acquisition funding for the OPC program for the construction of the second OPC (which is scheduled for delivery in 2022) and for procurement of long leadtime materials (LLTM) for the third OPC (which is scheduled for delivery in 2023).

|

Figure 4. Offshore Patrol Cutter Artist's rendering |

|

|

Source: Image received from Coast Guard liaison office, May 25, 2017. |

The Coast Guard's Request for Proposal (RFP) for the OPC program, released on September 25, 2012, established an affordability requirement for the program of an average unit price of $310 million per ship, or less, in then-year dollars (i.e., dollars that are not adjusted for inflation) for ships 4 through 9 in the program.21 This figure represents the shipbuilder's portion of the total cost of the ship; it does not include the cost of government-furnished equipment (GFE) on the ship,22 or other program costs—such as those for program management, system integration, and logistics—that contribute to the above-cited figure of $421 million per ship.23

At least eight shipyards expressed interest in the OPC program.24 On February 11, 2014, the Coast Guard announced that it had awarded Preliminary and Contract Design (P&CD) contracts to three of those eight firms—Bollinger Shipyards of Lockport, LA; Eastern Shipbuilding Group of Panama City, FL; and General Dynamics' Bath Iron Works (GD/BIW) of Bath, ME.25 On September 15, 2016, the Coast Guard announced that it had awarded the detail design and construction (DD&C) contract to Eastern Shipbuilding. The contract covers detail design and production of up to 9 OPCs and has a potential value of $2.38 billion if all options are exercised.26

For additional information on the status and execution of the OPC program from a May 2018 GAO report, see Appendix C.

FRC Program

Fast Response Cutters (Figure 5)—also called Sentinel (WPC-1101)27 class patrol boats because they are being named for enlisted leaders, trailblazers, and heroes of the Coast Guard and its predecessor services of the U.S. Revenue Cutter Service, U.S. Lifesaving Service, and U.S. Lighthouse Service28—are considerably smaller and less expensive than OPCs, but are larger than the Coast Guard's older patrol boats.29 FRCs are built by Bollinger Shipyards of Lockport, LA.

|

Figure 5. Fast Response Cutter With an older Island-class patrol boat behind |

|

|

Source: U.S. Coast Guard photo accessed May 4, 2012, at http://www.flickr.com/photos/coast_guard/6871815460/sizes/l/in/set-72157629286167596/. |

The Coast Guard's POR calls for procuring 58 FRCs as replacements for the service's 49 Island-class patrol boats.30 The Coast Guard's FY2019 budget submission estimated the total acquisition cost of the 58 cutters at $3.748.1 billion, or an average of about $65 million per cutter.31 A total of 56 FRCs have been funded through FY2019. The 29th was commissioned into service on November 8, 2018. The Coast Guard's proposed FY2019 budget requested $240 million in acquisition funding for the procurement of four more FRCs.

For additional information on the status and execution of the FRC program from a May 2018 GAO report, see Appendix C.

Funding in FY2013-FY2019 Budget Submissions

Table 1 shows annual requested and programmed acquisition funding for the NSC, OPC, and FRC programs in the Coast Guard's FY2013-FY2019 budget submissions. Actual appropriated figures differ from these requested and projected amounts.

Table 1. NSC, OPC, and FRC Funding in FY2013-FY2019 Budget Submissions

Figures in millions of then-year dollars

|

Budget |

FY13 |

FY14 |

FY15 |

FY16 |

FY17 |

FY18 |

FY19 |

FY20 |

FY21 |

FY22 |

FY23 |

|

NSC program |

|||||||||||

|

FY13 |

683 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

||||||

|

FY14 |

616 |

710 |

38 |

0 |

45 |

||||||

|

FY15 |

638 |

75 |

130 |

30 |

47 |

||||||

|

FY16 |

91.4 |

132 |

95 |

30 |

15 |

||||||

|

FY17 |

127 |

95 |

65 |

65 |

21 |

||||||

|

FY18 |

54 |

65 |

65 |

21 |

6.6 |

||||||

|

FY19 |

65 |

57.7 |

21 |

6.6 |

0 |

||||||

|

OPC program |

|||||||||||

|

FY13 |

30 |

50 |

40 |

200 |

530 |

||||||

|

FY14 |

25 |

65 |

200 |

530 |

430 |

||||||

|

FY15 |

20 |

90 |

100 |

530 |

430 |

||||||

|

FY16 |

18.5 |

100 |

530 |

430 |

430 |

||||||

|

FY17 |

100 |

530 |

430 |

530 |

770 |

||||||

|

FY18 |

500 |

400 |

457 |

716 |

700 |

||||||

|

FY19 |

400 |

457 |

716 |

700 |

689 |

||||||

|

FRC program |

|||||||||||

|

FY13 |

139 |

360 |

360 |

360 |

360 |

||||||

|

FY14 |

75 |

110 |

110 |

110 |

110 |

||||||

|

FY15 |

110 |

340 |

220 |

220 |

315 |

||||||

|

FY16 |

340 |

325 |

240 |

240 |

325 |

||||||

|

FY17 |

240 |

240 |

325 |

325 |

18 |

||||||

|

FY18 |

240 |

335 |

335 |

26 |

18 |

||||||

|

FY19 |

240 |

340 |

20 |

20 |

20 |

||||||

|

Total |

|||||||||||

|

FY13 |

852 |

410 |

400 |

560 |

890 |

||||||

|

FY14 |

716 |

885 |

348 |

640 |

585 |

||||||

|

FY15 |

768 |

505 |

450 |

780 |

792 |

||||||

|

FY16 |

449.9 |

557 |

865 |

700 |

370 |

||||||

|

FY17 |

467 |

865 |

820 |

920 |

809 |

||||||

|

FY18 |

794 |

800 |

857 |

763 |

724.6 |

||||||

|

FY19 |

705 |

854.7 |

757 |

726.6 |

709 |

||||||

Source: Table prepared by CRS based on FY2013-FY2019 budget submissions.

Note: n/a means not available.

Issues for Congress

Whether to Fund a 12th NSC

One issue for Congress is whether to fully or partially fund the acquisition of a 12th NSC. Based on funding provided by Congress for the procurement of the 11th NSC in FY2018, fully funding the procurement of a 12th might require about $635 million.

Supporters of procuring a 12th NSC could argue that a total of 12 NSCs would provide one-for-one replacements for the 12 retiring Hamilton-class cutters; that Coast Guard analyses showing a need for no more than 9 NSCs assumed dual crewing of NSCs—something that has not worked as well as expected; and that the Coast Guard's POR record includes only about 61% as many new cutters as the Coast Guard has calculated would be required to fully perform the Coast Guard's anticipated missions in coming years (see "Planned NSC, OPC, and FRC Procurement Quantities" below, as well as Appendix A).

Skeptics or opponents of procuring a 12th NSC in FY2019 could argue that the Coast Guard's POR includes only 8 NSCs, that the Coast Guard's fleet mix analyses (see "Planned NSC, OPC, and FRC Procurement Quantities" below, as well as Appendix A) have not shown a potential need for more than 9 NSCs, and that in a situation of finite Coast Guard budgets, funding a 12th NSC might require reducing funding for other Coast Guard programs.

Whether to End Procurement of FRCs at 58

Another issue for Congress is whether to end procurement of FRCs at the Coast Guard's planned total of 58 (which would imply the procurement of two final FRCs in FY2020), or instead continue procuring FRCs beyond the 58th. Supporters of ending FRC procurement at 58 could argue that 58 has long been the planned total number of FRCs, and that procuring additional FRCs beyond the 58th might require reducing funding for other Coast Guard programs. Supporters of continuing to procure FRCs beyond the 58th could argue that the Coast Guard's fleet mix analyses (see "Planned NSC, OPC, and FRC Procurement Quantities" below, as well as Appendix A) have shown a potential need for as many as 91 FRCs.

Annual or Multiyear (Block Buy) Contracting for OPCs

Another issue for Congress is whether to acquire OPCs using annual contracting or multiyear contracting. The Coast Guard currently plans to use a contract with options for procuring the first nine OPCs. Although a contract with options may look like a form of multiyear contracting, it operates more like a series of annual contracts. Contracts with options do not achieve the reductions in acquisition costs that are possible with multiyear contracting. Using multiyear contracting involves accepting certain trade-offs.32

One form of multiyear contracting, called block buy contracting, can be used at the start of a shipbuilding program, beginning with the first ship. (Indeed, this was a principal reason why block buy contracting was in effect invented in FY1998, as the contracting method for procuring the Navy's first four Virginia-class attack submarines.)33 Section 311 of the Frank LoBiondo Coast Guard Authorization Act of 2018 (S. 140/P.L. 115-282 of December 4, 2018) provides permanent authority for the Coast Guard to use block buy contracting with economic order quantity (EOQ) purchases (i.e., up-front batch purchases) of components in its major acquisition programs. The authority is now codified at 14 U.S.C. 1137.

CRS estimates that if the Coast Guard were to use block buy contracting with EOQ purchases of components for acquiring the first several OPCs, and either block buy contracting with EOQ purchases or another form of multiyear contracting known as multiyear procurement (MYP)34 with EOQ purchases for acquiring the remaining ships in the program, the savings on the total acquisition cost of the 25 OPCs (compared to costs under contracts with options) could amount to roughly $1 billion. CRS also estimates that acquiring the first nine ships in the OPC program under the current contract with options could forego roughly $350 million of the $1 billion in potential savings.

One potential option for the subcommittee would be to look into the possibility of having the Coast Guard either convert the current OPC contract at an early juncture into a block buy contract with EOQ authority, or, if conversion is not possible, replace the current contract at an early juncture with a block buy contract with EOQ authority.35 Replacing the current contract with a block buy contract might require recompeting the program, which would require effort on the Coast Guard's part and could create business risk for Eastern Shipbuilding Group, the shipbuilder that holds the current contract. On the other hand, the cost to the Coast Guard of recompeting the program would arguably be small relative to a potential additional savings of perhaps $300 million, and Eastern arguably would have a learning curve advantage in any new competition by virtue of its experience in building the first OPC.

Annual OPC Procurement Rate

The current procurement profile for the OPC, which reaches a maximum projected annual rate of two ships per year, would deliver OPCs many years after the end of the originally planned service lives of the medium-endurance cutters that they are to replace. Coast Guard officials have testified that the service plans to extend the service lives of the medium-endurance cutters until they are replaced by OPCs. There will be maintenance and repair expenses associated with extending the service lives of medium-endurance cutters, and if the Coast Guard does not also make investments to increase the capabilities of these ships, the ships may have less capability in certain regards than OPCs.36

One possible option for addressing this situation would be to increase the maximum annual OPC procurement rate from the currently planned two ships per year to three or four ships per year. Doing this could result in the 25th OPC being delivered about four years or six years sooner, respectively, than under the currently planned maximum rate. Increasing the OPC procurement rate to three or four ships per year would require a substantial increase to the Coast Guard's Procurement, Construction, and Improvements (PC&I) account,37 an issue discussed in Appendix B.

Increasing the maximum procurement rate for the OPC program could, depending on the exact approach taken, reduce OPC unit acquisition costs due to improved production economies of scale. Doubling the rate for producing a given OPC design to four ships per year, for example, could reduce unit procurement costs for that design by as much as 10%, which could result in hundreds of millions of dollars in additional savings in acquisition costs for the program. Increasing the maximum annual procurement rate could also create new opportunities for using competition in the OPC program. Notional alternative approaches for increasing the OPC procurement rate to three or four ships per year include but are not necessarily limited to the following:

- increasing the production rate to three or four ships per year at Eastern Shipbuilding—an option that would depend on Eastern Shipbuilding's production capacity;

- introducing a second shipyard to build Eastern's design for the OPC;

- introducing a second shipyard (such as one of the other two OPC program finalists) to build its own design for the OPC—an option that would result in two OPC classes; or

- building additional NSCs in the place of some of the OPCs—an option that might include descoping equipment on those NSCs where possible to reduce their acquisition cost and make their capabilities more like that of the OPC. Such an approach would be broadly similar to how the Navy is planning to use a descoped version of the San Antonio (LPD-17) class amphibious ship as the basis for its LPD-17 Flight II (LPD-30) class amphibious ships.38

Impact of Hurricane Michael on Eastern Shipbuilding

Another potential issue for Congress concerns the impact of Hurricane Michael on Eastern Shipbuilding of Panama City, FL, the shipyard that is to build the first nine OPCs. A January 28, 2019, press release from Eastern Shipbuilding stated:

Panama City, FL, Eastern Shipbuilding Group [ESG] reports that steel cutting for the first offshore patrol cutter (OPC), Coast Guard Cutter ARGUS (WMSM-915), commenced on January 7, 2019 at Eastern's facilities. ESG successfully achieved this milestone even with sustaining damage and work interruption due to Hurricane Michael. The cutting of steel will start the fabrication and assembly of the cutter's hull, and ESG is to complete keel laying of ARGUS later this year. Additionally, ESG completed the placement of orders for all long lead time materials for OPC #2, Coast Guard Cutter CHASE (WMSM-916).

Eastern's President Mr. Joey D'Isernia noted the following: "Today represents a monumental day and reflects the dedication of our workforce - the ability to overcome and perform even under the most strenuous circumstances and impacts of Hurricane Michael. ESG families have been dramatically impacted by the storm, and we continue to recover and help rebuild our shipyard and community. I cannot overstate enough how appreciative we are of all of our subcontractors and vendors contributions to our families during the recovery as well as the support we have received from our community partners. Hurricane Michael may have left its marks but it only strengthened our resolve to build the most sophisticated, highly capable national assets for the Coast Guard. Today's success is just the beginning of the construction of the OPCs at ESG by our dedicated team of shipbuilders and subcontractors for our customer and partner, the United States Coast Guard. We are excited for what will be a great 2019 for Eastern Shipbuilding Group and Bay County, Florida."39

A November 1, 2018, statement from Eastern Shipbuilding states that the firm

resumed operations at both of its two main shipbuilding facilities just two weeks after Hurricane Michael devastated Panama City Florida and the surrounding communities….

… the majority of ESG's [Eastern Shipbuilding Group's] workforce has returned to work very quickly despite the damage caused by the storm. "Our employees are a resourceful and resilient group of individuals with the drive to succeed in the face of adversity. This has certainly been proven by their ability to bounce back over the two weeks following the storm. Our employees have returned to work much faster than anticipated and brought with them an unbreakable spirit, that I believe sets this shipyard and our community apart" said [Eastern Shipbuilding] President Joey D'Isernia. "Today, our staffing levels exceed 80% of our pre-Hurricane Michael levels and is rising daily."

Immediately following the storm, ESG set out on an aggressive initiative to locate all of its employees and help get them back on the job as soon as practical after they took necessary time to secure the safety and security of their family and home. Together with its network of friends, partners, and customers in the maritime community, ESG organized daily distribution of meals and goods to employees in need. Additionally, ESG created an interest free deferred payback loan program for those employees in need and has organized Go Fund Me account to help those employees hardest hit by the storm. ESG also knew temporary housing was going to be a necessity in the short term and immediately built a small community located on greenfield space near its facilities for those employees with temporary housing needs.

ESG has worked closely with its federal, state and commercial partners over the past two weeks to provide updates on the shipyard as well as on projects currently under construction. Power was restored to ESG's Nelson Facility on 10-21-18 and at ESG's Allanton Facility on 10-24-18 and production of vessels under contract is ramping back up. Additionally, all of the ESG personnel currently working on the US Coast Guard's Offshore Patrol Cutter contract have returned to work….

"We are grateful to our partners and the maritime business community as a whole for their support and confidence during the aftermath of this historic storm. Seeing our incredible employees get back to building ships last week was an inspiration," said D'Isernia. "While there is no doubt that the effects of Hurricane Michael will linger with our community for years to come, I can say without reservation that we are open for business and excited about delivering quality vessels to our loyal customers."40

An October 22, 2018, press report states the following:

U.S. Coast Guard officials and Eastern Shipbuilding Group are still assessing the damage caused by deadly category 4 Hurricane Michael to the Panama City, Fla.-based yard contracted to build the new class of Offshore Patrol Cutters.

On September 28, the Coast Guard awarded Eastern Shipbuilding a contract to build the future USCGC Argus (WMSM-915), the first offshore patrol cutter (OPC). The yard was also set to build a second OPC, the future USCGC Chase (WMSM-916). Eastern Shipbuilding's contract is for nine OPCs, with options for two additional cutters. Ultimately, the Coast Guard plans to buy 25 OPCs.

However, just as the yard was preparing to build Argus, Hurricane Michael struck the Florida Panhandle near Panama City on October 10. Workers from the shipyard and Coast Guard project managers evacuated and are just now returning to assess damage to the yard facilities, Brian Olexy, communications manager for the Coast Guard's Acquisitions Directorate, told USNI News.

"Right now we haven't made any decisions yet on shifts in schedule," Olexy said….

Since the yard was just the beginning stages of building Argus, Olexy said the hull wasn't damaged. "No steel had been cut," he said.

Eastern Shipbuilding is still in the process of assessing damage to the yard and trying to reach its workforce. Many employees evacuated the area and have not returned, or are in the area but lost their homes, Eastern Shipbuilding spokesman Justin Smith told USNI News.

At first, about 200 workers returned to work, but by week's end about 500 were at the yard, Smith said. The company is providing meals, water, and ice for its workforce.

"Although we were significantly impacted by this catastrophic weather event, we are making great strides each day thanks to the strength and resiliency of our employees," Joey D'Isernia, president of Eastern Shipbuilding, said in a statement.41

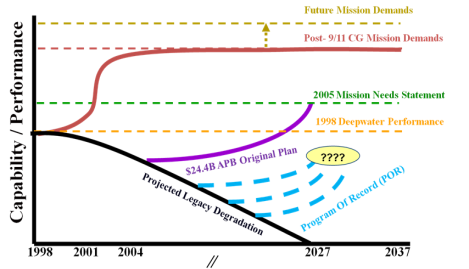

Planned NSC, OPC, and FRC Procurement Quantities

Another issue for Congress concerns the Coast Guard's planned NSC, OPC, and FRC procurement quantities. The POR's planned force of 91 NSCs, OPCs, and FRCs is about equal in number to the Coast Guard's legacy force of 90 high-endurance cutters, medium-endurance cutters, and 110-foot patrol craft. NSCs, OPCs, and FRCs, moreover, are to be individually more capable than the older ships they are to replace. Even so, Coast Guard studies have concluded that the planned total of 91 NSCs, OPCs, and FRCs would provide 61% of the cutters that would be needed to fully perform the service's statutory missions in coming years, in part because Coast Guard mission demands are expected to be greater in coming years than they were in the past. For further discussion of this issue, about which CRS has testified and reported on since 2005,42 see Appendix A.

Legislative Activity in 2018

Summary of Appropriations Action on FY2019 Acquisition Funding Request

Table 2 summarizes appropriations action on the Coast Guard's request for FY2019 acquisition funding for the NSC, OPC, and FRC programs.

Table 2. Summary of Appropriations Action on FY2019 Acquisition Funding Request

Figures in millions of dollars, rounded to nearest tenth

|

Request |

Request |

HAC |

SAC |

Final |

|

NSC program |

65 |

140 |

72.6 |

72.6 |

|

OPC program |

400 |

400 |

400 |

400 |

|

FRC program |

240 |

340 |

240 |

340 |

|

TOTAL |

705 |

880 |

712.6 |

812.6 |

Source: Table prepared by CRS based on Coast Guard's FY2019 budget submission, HAC committee report, and SAC chairman's mark and explanatory statement on FY2019 DHS Appropriations Act. HAC is House Appropriations Committee; SAC is Senate Appropriations Committee.

FY2019 DHS Appropriations Act (Division A of H.J.Res. 31/H.R. XXXX/S. 3109)

House

The House Appropriations Committee marked up the FY2019 DHS Appropriations Act (referred to here as H.R. XXXX) on July 25, 2018. The text of the bill as marked up, and the committee's report reflecting the markup, were not available as of August 3, 2018. The figures shown in the HAC column of Table 2 and the discussion below are based on the bill text and draft committee report (referred to here as H.Rept. 115-XXX) going into the July 25, 2018, markup meeting, combined with a summary of the amendments adopted at the markup meeting, which were posted on the committee's website in conjunction with the pre-markup bill text and draft committee report.43

H.Rept. 115-XXX recommends the funding levels shown in the HAC column of Table 2. In addition, the committee states that at the July 25, 2018, markup, the committee adopted by voice vote an amendment that "allows certain existing, unobligated funds to be used to purchase long-lead time materials for the 12th National Security Cutter."

H.Rept. 115-XXX states the following:

National Security Cutter (NSC). The Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2018 (Public Law 115–141) provided $1,241,000,000 for the NSC program, which included funds for construction of the tenth and eleventh NSC, a contrast from the historic approach of funding construction for one NSC per fiscal year. The Committee's fiscal year 2019 recommendation includes $140,000,000 for the NSC program, $75,000,000 more than requested. Included in this amount is an additional $75,000,000 above the request to continue support of Post Delivery Activities (PDA) for the seventh through ninth hulls and other program-wide activities.

Offshore Patrol Cutter (OPC). The recommendation includes $400,000,000 for the OPC program, as requested, to fund construction of the second OPC, long lead time materials for the third, and program management costs.

Fast Response Cutter (FRC). The recommendation provides $340,000,000 for six FRCs, four for the current program of record, as requested, and two to continue replacement of the 110-foot Island Class Cutters supporting U.S. Central Command in Southwest Asia. The Committee strongly encourages the Coast Guard to transition the 110-foot patrol boats supporting U.S. Central Command in Southwest Asia to FRCs in the most expedient manner possible, and to update the Committee of any changes to its FRC deployment strategy. The Committee understands the current patrol boats are well past their service life and wants to ensure the Coast Guard men and women serving in this challenging area of operations have the right equipment necessary to meet these evolving threats. (Page 39)

H.Rept. 115-XXX also states the following:

Similar to the other Armed Services, the Coast Guard must maintain military readiness in order to meet its mission requirements. Within 180 days of enactment of this Act, the Coast Guard is directed to report to the Committee on any lost operational time due to unplanned maintenance or supply shortfalls for cutters, aircraft, and boats, as well as the current operations and support (O&S) maintenance backlog for cutters, aircraft, shore facilities, and information technology systems, including the operational impact of this backlog.

he Committee recommends $7,620,209,000 for [the Coast Guard] O&S [operation and support account], $27,071,000 above the request to fund additional full-time equivalents, increase child care subsidy benefits, fund an independent analysis of the current and projected air and sea fleet requirements, and address rising costs for fuel and rent. Also included in this amount is $1,000,000 to equip the Fast Response Cutter fleet with hailing and acoustic laser light tactical systems. (Page 36)

H.Rept. 115-XXX also states the following:

The Commandant of the Coast Guard is directed to provide to the Committee not later than one year after the date of enactment of this Act, a report that examines the number and type of Coast Guard assets required to meet the Service's current and foreseeable needs in accordance with the Service's statutory missions. The report shall include, but not be limited to, an assessment of the required number and types of cutters and aircraft for current and planned asset acquisitions. The report shall specifically address regional mission requirements in the Western Hemisphere, including the Polar regions, support provided to Combatant Commanders, and trends in illicit activity and illegal migration. In order to provide an impartial assessment, the recommendation includes an increase of $3,300,000 for the report to be prepared by a Federally Funded Research and Development Center experienced in similar examinations. (Page 37)

Senate

The Senate Appropriations Committee, in its report (S.Rept. 115-283 of June 21, 2018) on S. 3109, recommends the funding levels shown in the SAC column of Table 2. S.Rept. 115-283 states the following:

National Security Cutter.—Legend Class National Security Cutters [NSCs] are replacing the legacy High Endurance Cutters, built between 1967 and 1972. In fiscal year 2017, the Coast Guard interdicted 2,512 illegal migrants and removed 224 metric tons of cocaine with an estimated street value of over $6,600,000,000, which surpassed the previous record amount of cocaine removal set the previous fiscal year. Of the 224 metric tons of cocaine removed, four NSCs interdicted 72.6 metric tons of cocaine with an estimated street value of $2,144,000,000. In a single deployment, the USCGC JAMES (WMSL–754) removed 16.8 metric tons of uncut cocaine with a street value in excess of $496,000,000. The Committee recommends $72,600,000 for the NSC program including $7,600,000 for advance purchase of several systems for the tenth and eleventh NSCs, including wind indicating and measurement systems, homing beacons for aircraft, and navigation and sensor data distribution systems. The Committee worked diligently to ensure resources were provided by the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2018 to construct a tenth and eleventh NSC. The Committee is pleased that the Coast Guard has indicated that contracts for these NSCs are on track to be awarded on time. The Committee continues to believe that the Coast Guard's fleet of twelve High Endurance Cutters should be replaced with twelve NSCs. The Committee intends to continue to work with the Coast Guard to understand the costs, operational benefits of, and recommended schedule for acquisition of a twelfth NSC.

Offshore Patrol Cutter.—The OPC will replace the fleet of Medium Endurance Cutters and further enhance the Coast Guard's layered security strategy. The recommendation includes $400,000,000 for the OPC program. This funding will provide for production of a second OPC, LLTM for a third OPC, program activities, test and evaluation, government furnished equipment, and training aids. The Committee encourages the Coast Guard to evaluate the requirements for a sensitive compartmented information facility and a multimodal radar system onboard the OPC and determine whether and when these requirements should be incorporated into revised design and construction.

Fast Response Cutter.—The Committee recommends $240,000,000 to acquire four FRCs, as requested. (Page 68)

S.Rept. 115-283 also states the following:

Due in large part to the Committee's efforts, the Coast Guard's surface and air fleets are in the midst of unprecedented modernization. With the expansion of the National Security Cutter fleet, continuation of Fast Response Cutter production, beginning of the Offshore Patrol Cutter acquisition, and initiation of the first Heavy Polar Icebreaker acquisition in more than four decades, the Coast Guard's cutter fleet is growing into a state-of-the-art force adaptable to any mission. (Page 6)

S.Rept. 115-283 also states the following:

Coast Guard Yard.—The Committee has urged the Coast Guard to expedite planning for facility and equipment upgrades necessary for service life extensions of the Fast Response Cutter [FRC] and other vessels at the Coast Guard Yard at Curtis Bay in Baltimore, Maryland. The nearest travel lift of sufficient size and capacity to service the FRC is in Hampton Roads, Virginia. Transporting the travel lift between Hampton Roads and Baltimore is a costly and time consuming procedure that removes the lift from service during transport. The recommendation includes funding within the PC&I appropriation to acquire necessary equipment and make physical modifications to wharves or other parts of the Coast Guard Yard facility to accommodate FRCs and other vessels. (Page 63)

S.Rept. 115-283 also states the following:

Full-Funding Policy.—The Committee again directs an exception to the administration's current acquisition policy that requires the Coast Guard to attain the total acquisition cost for a vessel, including long lead time materials [LLTM], production costs, and postproduction costs, before a production contract can be awarded. This policy has the potential to make shipbuilding less efficient, to force delayed obligation of production funds, and to require post-production funds far in advance of when they will be used. The Department should position itself to acquire vessels in the most efficient manner within the guidelines of strict governance measures. The Committee expects the administration to adopt a similar policy for the acquisition of the Offshore Patrol Cutter [OPC] and heavy polar icebreaker. (Page 67)

S.Rept. 115-283 also states the following:

Homeport of New Vessels.—The Committee supports the current and planned homeport locations for National Security Cutters. However, the Committee recognizes the challenges that replacing the 378-foot Hamilton-class cutter with 418-foot NSCs has imposed on Coast Guard facilities where waterfront space is limited and reiterates the importance of pier availability for Coast Guard cutters and other surface vessels to minimize operational delays or other unnecessary costs that would undermine the Coast Guard's ability to conduct its missions. Therefore, not later than 180 days after enactment of this act, the Coast Guard shall report to the Committee on infrastructure requirements associated with the homeporting of new vessels. At a minimum, the Coast Guard shall assess if major acquisition system infrastructure is required, identify associated funding needs, and provide a plan to address these requirements to the Committee. (Pages 70-71)

Conference

In final action, the FY2019 DHS Appropriations Act became Division A of H.J.Res. 31 of the 116th Congress, a bill making consolidated appropriations for the fiscal year ending September 30, 2019, and for other purposes. The joint explanatory statement for H.J.Res. 31 provides the funding levels shown in the conference column of Table 2. The increase of $7.6 million for the NSC program includes $5 million for post-delivery activities for the 10th NSC and $2.6 million for post-delivery activities for the 11th NSC. The increase of $100 million for the FRC program is for "additional Fast Response Cutters as described on page 43 of H.Rept. 115-948." (PDF pages 26 and 66 of 609).

Frank LoBiondo Coast Guard Authorization Act of 2018 (S. 140/P.L. 115-282)

S. 140 was introduced in the Senate on January 12, 2017, as a bill to amend the White Mountain Apache Tribe [WMAT] Water Rights Quantification Act of 2010 to clarify the use of amounts in the WMAT Settlement Fund. The bill retained that purpose and was acted on by Congress into 2018. Later in 2018, S. 140 became a bill to authorize appropriations for the Coast Guard, and for other purposes. On November 14, 2018, the Senate concurred, 94-6, in the House amendment to S. 140 with an amendment (S.Amdt. 4054 as modified). On November 27, 2018, the House agreed to by voice vote a motion that the House suspend the rules and agree to the Senate amendment to the House amendment. S. 140 was signed into law as P.L. 115-282 on December 4, 2018.

Section 204 of S. 140/P.L. 115-282 states the following:

SEC. 204. Authorization of amounts for Fast Response Cutters.

(a) In general.—Of the amounts authorized under section 4902 of title 14, United States Code, as amended by this Act, for each of fiscal years 2018 and 2019 up to $167,500,000 is authorized for the acquisition of 3 Fast Response Cutters.

(b) Treatment of acquired cutters.—Any cutters acquired pursuant to subsection (a) shall be in addition to the 58 cutters approved under the existing acquisition baseline.

Section 304 of S. 140/P.L. 115-282 states the following:

SEC. 304. Unmanned aircraft.

(a) Land-based unmanned aircraft system program.—Chapter 3 of title 14, United States Code, is amended by adding at the end the following:

"§ 319. Land-based unmanned aircraft system program

"(a) In general.—Subject to the availability of appropriations, the Secretary shall establish a land-based unmanned aircraft system program under the control of the Commandant.

"(b) Unmanned aircraft system defined.—In this section, the term 'unmanned aircraft system' has the meaning given that term in section 331 of the FAA Modernization and Reform Act of 2012 (49 U.S.C. 40101 note).".

(b) Limitation on unmanned aircraft systems.—Chapter 11 of title 14, United States Code, is amended by inserting after section 1155 the following:

"§ 1156. Limitation on unmanned aircraft systems

"(a) In general.—During any fiscal year for which funds are appropriated for the design or construction of an Offshore Patrol Cutter, the Commandant—

"(1) may not award a contract for design of an unmanned aircraft system for use by the Coast Guard; and

"(2) may lease, acquire, or acquire the services of an unmanned aircraft system only if such system—

"(A) has been part of a program of record of, procured by, or used by a Federal entity (or funds for research, development, test, and evaluation have been received from a Federal entity with regard to such system) before the date on which the Commandant leases, acquires, or acquires the services of the system; and

"(B) is leased, acquired, or utilized by the Commandant through an agreement with a Federal entity, unless such an agreement is not practicable or would be less cost-effective than an independent contract action by the Coast Guard.

"(b) Small unmanned aircraft exemption.—Subsection (a)(2) does not apply to small unmanned aircraft.

"(c) Definitions.—In this section, the terms 'small unmanned aircraft' and 'unmanned aircraft system' have the meanings given those terms in section 331 of the FAA Modernization and Reform Act of 2012 (49 U.S.C. 40101 note).".

(c) Clerical amendments.—

(1) CHAPTER 3.—The analysis for chapter 3 of title 14, United States Code, is amended by adding at the end the following:

"319. Land-based unmanned aircraft system program.".

(2) CHAPTER 11.—The analysis for chapter 11 of title 14, United States Code, is amended by inserting after the item relating to section 1155 the following:

"1156. Limitation on unmanned aircraft systems.".

(d) Conforming amendment.—Subsection (c) of section 1105 of title 14, United States Code, is repealed.

Section 311 of S. 140/P.L. 115-282 states the following:

SEC. 311. Contracting for major acquisitions programs.

(a) General acquisition authority.—Section 501(d) of title 14, United States Code, is amended by inserting "aircraft, and systems," after "vessels,".

(b) Contracting authority.—Chapter 11 of title 14, United States Code, as amended by this Act, is further amended by inserting after section 1136 the following:

"§ 1137. Contracting for major acquisitions programs

"(a) In general.—In carrying out authorities provided to the Secretary to design, construct, accept, or otherwise acquire assets and systems under section 501(d), the Secretary, acting through the Commandant or the head of an integrated program office established for a major acquisition program, may enter into contracts for a major acquisition program.

"(b) Authorized methods.—Contracts entered into under subsection (a)—

"(1) may be block buy contracts;

"(2) may be incrementally funded;

"(3) may include combined purchases, also known as economic order quantity purchases, of—

"(A) materials and components; and

"(B) long lead time materials; and

"(4) as provided in section 2306b of title 10, may be multiyear contracts.

"(c) Subject to appropriations.—Any contract entered into under subsection (a) shall provide that any obligation of the United States to make a payment under the contract is subject to the availability of amounts specifically provided in advance for that purpose in subsequent appropriations Acts.".

(c) Clerical amendment.—The analysis for chapter 11 of title 14, United States Code, as amended by this Act, is further amended by inserting after the item relating to section 1136 the following:

"1137. Contracting for major acquisitions programs.".

(d) Conforming amendments.—The following provisions are repealed:

(1) Section 223 of the Howard Coble Coast Guard and Maritime Transportation Act of 2014 (14 U.S.C. 1152 note), and the item relating to that section in the table of contents in section 2 of such Act.

(2) Section 221(a) of the Coast Guard and Maritime Transportation Act of 2012 (14 U.S.C. 1133 note).

(3) Section 207(a) of the Coast Guard Authorization Act of 2016 (14 U.S.C. 561 note).

(e) Internal regulations and policy.—Not later than 180 days after the date of enactment of this Act, the Secretary of the department in which the Coast Guard is operating shall establish the internal regulations and policies necessary to exercise the authorities provided under this section, including the amendments made in this section.

(f) Multiyear contracts.—The Secretary of the department in which the Coast Guard is operating is authorized to enter into a multiyear contract for the procurement of a tenth, eleventh, and twelfth National Security Cutter and associated government-furnished equipment.

Section 817 of S. 140/P.L. 115-282 states the following:

SEC. 817. Fleet requirements assessment and strategy.

(a) Report.—Not later than 1 year after the date of enactment of this Act, the Secretary of the department in which the Coast Guard is operating, in consultation with interested Federal and non-Federal stakeholders, shall submit to the Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation of the Senate and the Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure of the House of Representatives a report including—

(1) an assessment of Coast Guard at-sea operational fleet requirements to support its statutory missions established in the Homeland Security Act of 2002 (6 U.S.C. 101 et seq.); and

(2) a strategic plan for meeting the requirements identified under paragraph (1).

(b) Contents.—The report under subsection (a) shall include—

(1) an assessment of—

(A) the extent to which the Coast Guard at-sea operational fleet requirements referred to in subsection (a)(1) are currently being met;

(B) the Coast Guard's current fleet, its operational lifespan, and how the anticipated changes in the age and distribution of vessels in the fleet will impact the ability to meet at-sea operational requirements;

(C) fleet operations and recommended improvements to minimize costs and extend operational vessel life spans; and

(D) the number of Fast Response Cutters, Offshore Patrol Cutters, and National Security Cutters needed to meet at-sea operational requirements as compared to planned acquisitions under the current programs of record;

(2) an analysis of—

(A) how the Coast Guard at-sea operational fleet requirements are currently met, including the use of the Coast Guard's current cutter fleet, agreements with partners, chartered vessels, and unmanned vehicle technology; and

(B) whether existing and planned cutter programs of record (including the Fast Response Cutter, Offshore Patrol Cutter, and National Security Cutter) will enable the Coast Guard to meet at-sea operational requirements; and

(3) a description of—

(A) planned manned and unmanned vessel acquisition; and

(B) how such acquisitions will change the extent to which the Coast Guard at-sea operational requirements are met.

(c) Consultation and transparency.—

(1) CONSULTATION.—In consulting with the Federal and non-Federal stakeholders under subsection (a), the Secretary of the department in which the Coast Guard is operating shall—

(A) provide the stakeholders with opportunities for input—

(i) prior to initially drafting the report, including the assessment and strategic plan; and

(ii) not later than 3 months prior to finalizing the report, including the assessment and strategic plan, for submission; and

(B) document the input and its disposition in the report.

(2) TRANSPARENCY.—All input provided under paragraph (1) shall be made available to the public.

(d) Ensuring maritime coverage.—In order to meet Coast Guard mission requirements for search and rescue, ports, waterways, and coastal security, and maritime environmental response during recapitalization of Coast Guard vessels, the Coast Guard shall ensure continuity of the coverage, to the maximum extent practicable, in the locations that may lose assets.

Section 818 of S. 140/P.L. 115-282 states the following:

SEC. 818. National Security Cutter.

(a) Standard method for tracking.—The Commandant of the Coast Guard may not certify an eighth National Security Cutter as Ready for Operations before the date on which the Commandant provides to the Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure of the House of Representatives and the Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation of the Senate—

(1) a notification of a new standard method for tracking operational employment of Coast Guard major cutters that does not include time during which such a cutter is away from its homeport for maintenance or repair; and

(2) a report analyzing cost and performance for different approaches to achieving varied levels of operational employment using the standard method required by paragraph (1) that, at a minimum—

(A) compares over a 30-year period the average annualized baseline cost and performances for a certified National Security Cutter that operated for 185 days away from homeport or an equivalent alternative measure of operational tempo—

(i) against the cost of a 15 percent increase in days away from homeport or an equivalent alternative measure of operational tempo for a National Security Cutter; and

(ii) against the cost of the acquisition and operation of an additional National Security Cutter; and

(B) examines the optimal level of operational employment of National Security Cutters to balance National Security Cutter cost and mission performance.

(b) Conforming amendments.—

(1) Section 221(b) of the Coast Guard and Maritime Transportation Act of 2012 (126 Stat. 1560) is repealed.

(2) Section 204(c)(1) of the Coast Guard Authorization Act of 2016 (130 Stat. 35) is repealed.

Section 822 of S. 140/P.L. 115-282 states the following:

SEC. 822. Strategic assets in the Arctic.

(a) Definition of arctic.—In this section, the term "Arctic" has the meaning given the term in section 112 of the Arctic Research and Policy Act of 1984 (15 U.S.C. 4111).

(b) Sense of congress.—It is the sense of Congress that—

(1) the Arctic continues to grow in significance to both the national security interests and the economic prosperity of the United States; and

(2) the Coast Guard must ensure it is positioned to respond to any accident, incident, or threat with appropriate assets.

(c) Report.—Not later than 1 year after the date of enactment of this Act, the Commandant of the Coast Guard, in consultation with the Secretary of Defense and taking into consideration the Department of Defense 2016 Arctic Strategy, shall submit to the Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation of the Senate and the Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure of the House of Representatives a report on the progress toward implementing the strategic objectives described in the United States Coast Guard Arctic Strategy dated May 2013.

(d) Contents.—The report under subsection (c) shall include—

(1) a description of the Coast Guard's progress toward each strategic objective identified in the United States Coast Guard Arctic Strategy dated May 2013;

(2) an assessment of the assets and infrastructure necessary to meet the strategic objectives identified in the United States Coast Guard Arctic Strategy dated May 2013 based on factors such as—

(A) response time;

(B) coverage area;

(C) endurance on scene;

(D) presence; and

(E) deterrence;

(3) an analysis of the sufficiency of the distribution of National Security Cutters, Offshore Patrol Cutters, and Fast Response Cutters both stationed in various Alaskan ports and in other locations to meet the strategic objectives identified in the United States Coast Guard Arctic Strategy, dated May 2013;

(4) plans to provide communications throughout the entire Coastal Western Alaska Captain of the Port zone to improve waterway safety and mitigate close calls, collisions, and other dangerous interactions between the shipping industry and subsistence hunters;

(5) plans to prevent marine casualties, when possible, by ensuring vessels avoid environmentally sensitive areas and permanent security zones;

(6) an explanation of—

(A) whether it is feasible to establish a vessel traffic service, using existing resources or otherwise; and

(B) whether an Arctic Response Center of Expertise is necessary to address the gaps in experience, skills, equipment, resources, training, and doctrine to prepare, respond to, and recover spilled oil in the Arctic; and

(7) an assessment of whether sufficient agreements are in place to ensure the Coast Guard is receiving the information it needs to carry out its responsibilities.

Coast Guard Authorization Act of 2017 (Division D of National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2019 [H.R. 5515/P.L. 115-232])

House Floor Action

On May 22, 2018, as part of its consideration of the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2019 (H.R. 5515), the House agreed to by voice vote H.Amdt. 641, an en bloc amendment that included, inter alia, amendment number 52 as printed in H.Rept. 115-702 of May 22, 2018, on H.Res. 908, providing for the further consideration of H.R. 5515. Amendment number 52 added to H.R. 5515, as a new Division D, the Coast Guard Authorization Act of 2017.

Section 4204 within Division D states the following:

SEC. 4204. Authorization of amounts for Fast Response Cutters.

(a) In general.—Of the amounts authorized under section 4902 of title 14, United States Code, as amended by this division, for each of fiscal years 2018 and 2019 up to $167,500,000 is authorized for the acquisition of 3 Fast Response Cutters.

(b) Treatment of acquired cutters.—Any cutters acquired pursuant to subsection (a) shall be in addition to the 58 cutters approved under the existing acquisition baseline.

Section 4304 within Division D states the following (emphasis added):

SEC. 4304. Unmanned aircraft.

(a) Land-based unmanned aircraft system program.—Chapter 3 of title 14, United States Code, is amended by adding at the end the following:

"§ 319. Land-based unmanned aircraft system program

"(a) In general.—Subject to the availability of appropriations, the Secretary shall establish a land-based unmanned aircraft system program under the control of the Commandant.

"(b) Unmanned aircraft system defined.—In this section, the term 'unmanned aircraft system' has the meaning given that term in section 331 of the FAA Modernization and Reform Act of 2012 (49 U.S.C. 40101 note).".

(b) Limitation on unmanned aircraft systems.—Chapter 11 of title 14, United States Code, is amended by inserting after section 1154 the following:

"§ 1155. Limitation on unmanned aircraft systems

"(a) In general.—During any fiscal year for which funds are appropriated for the design or construction of an Offshore Patrol Cutter, the Commandant—

"(1) may not award a contract for design of an unmanned aircraft system for use by the Coast Guard; and

"(2) may lease, acquire, or acquire the services of an unmanned aircraft system only if such system—

"(A) has been part of a program of record of, procured by, or used by a Federal entity (or funds for research, development, test, and evaluation have been received from a Federal entity with regard to such system) before the date on which the Commandant leases, acquires, or acquires the services of the system; and

"(B) is leased, acquired, or utilized by the Commandant through an agreement with a Federal entity, unless such an agreement is not practicable or would be less cost-effective than an independent contract action by the Coast Guard.

"(b) Small unmanned aircraft exemption.—Subsection (a)(2) does not apply to small unmanned aircraft.

"(c) Definitions.—In this section, the terms 'small unmanned aircraft' and 'unmanned aircraft system' have the meanings given those terms in section 331 of the FAA Modernization and Reform Act of 2012 (49 U.S.C. 40101 note).".

(c) Clerical amendments.—

(1) CHAPTER 3.—The analysis for chapter 3 of title 14, United States Code, is amended by adding at the end the following:

"319. Land-based unmanned aircraft system program.".

(2) CHAPTER 11.—The analysis for chapter 11 of title 14, United States Code, is amended by inserting after the item relating to section 1154 the following:

"1155. Limitation on unmanned aircraft systems.".

(d) Conforming amendment.—Subsection (c) of section 1105 of title 14, United States Code, is repealed.

Section 4311 within Division D states the following:

SEC. 4311. Contracting for major acquisitions programs.

(a) General acquisition authority.—Section 501(d) of title 14, United States Code, is amended by inserting "aircraft, and systems," after "vessels,".

(b) Contracting authority.—Chapter 11 of title 14, United States Code, as amended by this division, is further amended by inserting after section 1136 the following:

"§ 1137. Contracting for major acquisitions programs

"(a) In general.—In carrying out authorities provided to the Secretary to design, construct, accept, or otherwise acquire assets and systems under section 501(d), the Secretary, acting through the Commandant or the head of an integrated program office established for a major acquisition program, may enter into contracts for a major acquisition program.

"(b) Authorized methods.—Contracts entered into under subsection (a)—

"(1) may be block buy contracts;

"(2) may be incrementally funded;

"(3) may include combined purchases, also known as economic order quantity purchases, of—

"(A) materials and components; and

"(B) long lead time materials; and

"(4) as provided in section 2306b of title 10, may be multiyear contracts.

"(c) Subject to appropriations.—Any contract entered into under subsection (a) shall provide that any obligation of the United States to make a payment under the contract is subject to the availability of amounts specifically provided in advance for that purpose in subsequent appropriations Acts.".

(c) Clerical amendment.—The analysis for chapter 11 of title 14, United States Code, as amended by this division, is further amended by inserting after the item relating to section 1136 the following:

"1137. Contracting for major acquisitions programs.".

(d) Conforming amendments.—The following provisions are repealed:

(1) Section 223 of the Howard Coble Coast Guard and Maritime Transportation Act of 2014 (14 U.S.C. 1152 note), and the item relating to that section in the table of contents in section 2 of such Act.

(2) Section 221(a) of the Coast Guard and Maritime Transportation Act of 2012 (14 U.S.C. 1133 note).

(3) Section 207(a) of the Coast Guard Authorization Act of 2016 (14 U.S.C. 561 note).

(e) Internal regulations and policy.—Not later than 180 days after the date of enactment of this Act, the Secretary of the department in which the Coast Guard is operating shall establish the internal regulations and policies necessary to exercise the authorities provided under this section, including the amendments made in this section.

(f) Multiyear contracts.—The Secretary of the department in which the Coast Guard is operating is authorized to enter into a multiyear contract for the procurement of a tenth, eleventh, and twelfth National Security Cutter and associated government-furnished equipment.

Section 4817 within Division D states the following:

SEC. 4817. Fleet requirements assessment and strategy.

(a) Report.—Not later than 1 year after the date of enactment of this Act, the Secretary of the department in which the Coast Guard is operating, in consultation with interested Federal and non-Federal stakeholders, shall submit to the Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation of the Senate and the Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure of the House of Representatives a report including—

(1) an assessment of Coast Guard at-sea operational fleet requirements to support its statutory missions established in the Homeland Security Act of 2002 (6 U.S.C. 101 et seq.); and

(2) a strategic plan for meeting the requirements identified under paragraph (1).

(b) Contents.—The report under subsection (a) shall include—

(1) an assessment of—

(A) the extent to which the Coast Guard at-sea operational fleet requirements referred to in subsection (a)(1) are currently being met;

(B) the Coast Guard's current fleet, its operational lifespan, and how the anticipated changes in the age and distribution of vessels in the fleet will impact the ability to meet at-sea operational requirements;

(C) fleet operations and recommended improvements to minimize costs and extend operational vessel life spans; and

(D) the number of Fast Response Cutters, Offshore Patrol Cutters, and National Security Cutters needed to meet at-sea operational requirements as compared to planned acquisitions under the current programs of record;

(2) an analysis of—

(A) how the Coast Guard at-sea operational fleet requirements are currently met, including the use of the Coast Guard's current cutter fleet, agreements with partners, chartered vessels, and unmanned vehicle technology; and

(B) whether existing and planned cutter programs of record (including the Fast Response Cutter, Offshore Patrol Cutter, and National Security Cutter) will enable the Coast Guard to meet at-sea operational requirements; and

(3) a description of—

(A) planned manned and unmanned vessel acquisition; and

(B) how such acquisitions will change the extent to which the Coast Guard at-sea operational requirements are met.

(c) Consultation and transparency.—

(1) CONSULTATION.—In consulting with the Federal and non-Federal stakeholders under subsection (a), the Secretary of the department in which the Coast Guard is operating shall—

(A) provide the stakeholders with opportunities for input—

(i) prior to initially drafting the report, including the assessment and strategic plan; and

(ii) not later than 3 months prior to finalizing the report, including the assessment and strategic plan, for submission; and

(B) document the input and its disposition in the report.

(2) TRANSPARENCY.—All input provided under paragraph (1) shall be made available to the public.

(d) Ensuring maritime coverage.—In order to meet Coast Guard mission requirements for search and rescue, ports, waterways, and coastal security, and maritime environmental response during recapitalization of Coast Guard vessels, the Coast Guard shall ensure continuity of the coverage, to the maximum extent practicable, in the locations that may lose assets.

Section 4818 within Division D states the following:

SEC. 4818. National Security Cutter.

(a) Standard method for tracking.—The Commandant of the Coast Guard may not certify an eighth National Security Cutter as Ready for Operations before the date on which the Commandant provides to the Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure of the House of Representatives and the Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation of the Senate—

(1) a notification of a new standard method for tracking operational employment of Coast Guard major cutters that does not include time during which such a cutter is away from its homeport for maintenance or repair; and

(2) a report analyzing cost and performance for different approaches to achieving varied levels of operational employment using the standard method required by paragraph (1) that, at a minimum—

(A) compares over a 30-year period the average annualized baseline cost and performances for a certified National Security Cutter that operated for 185 days away from homeport or an equivalent alternative measure of operational tempo—

(i) against the cost of a 15 percent increase in days away from homeport or an equivalent alternative measure of operational tempo for a National Security Cutter; and

(ii) against the cost of the acquisition and operation of an additional National Security Cutter; and

(B) examines the optimal level of operational employment of National Security Cutters to balance National Security Cutter cost and mission performance.

(b) Conforming amendments.—

(1) Section 221(b) of the Coast Guard and Maritime Transportation Act of 2012 (126 Stat. 1560) is repealed.

(2) Section 204(c)(1) of the Coast Guard Authorization Act of 2016 (130 Stat. 35) is repealed.

Section 4822 within Division D states the following (emphasis added):

SEC. 4822. Strategic assets in the Arctic.

(a) Definition of arctic.—In this section, the term "Arctic" has the meaning given the term in section 112 of the Arctic Research and Policy Act of 1984 (15 U.S.C. 4111).

(b) Sense of congress.—It is the sense of Congress that—

(1) the Arctic continues to grow in significance to both the national security interests and the economic prosperity of the United States; and

(2) the Coast Guard must ensure it is positioned to respond to any accident, incident, or threat with appropriate assets.

(c) Report.—Not later than 1 year after the date of enactment of this Act, the Commandant of the Coast Guard, in consultation with the Secretary of Defense and taking into consideration the Department of Defense 2016 Arctic Strategy, shall submit to the Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation of the Senate and the Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure of the House of Representatives a report on the progress toward implementing the strategic objectives described in the United States Coast Guard Arctic Strategy dated May 2013.

(d) Contents.—The report under subsection (c) shall include—

(1) a description of the Coast Guard's progress toward each strategic objective identified in the United States Coast Guard Arctic Strategy dated May 2013;

(2) an assessment of the assets and infrastructure necessary to meet the strategic objectives identified in the United States Coast Guard Arctic Strategy dated May 2013 based on factors such as—

(A) response time;

(B) coverage area;

(C) endurance on scene;

(D) presence; and

(E) deterrence;

(3) an analysis of the sufficiency of the distribution of National Security Cutters, Offshore Patrol Cutters, and Fast Response Cutters both stationed in various Alaskan ports and in other locations to meet the strategic objectives identified in the United States Coast Guard Arctic Strategy, dated May 2013;

(4) plans to provide communications throughout the entire Coastal Western Alaska Captain of the Port zone to improve waterway safety and mitigate close calls, collisions, and other dangerous interactions between the shipping industry and subsistence hunters;

(5) plans to prevent marine casualties, when possible, by ensuring vessels avoid environmentally sensitive areas and permanent security zones;

(6) an explanation of—

(A) whether it is feasible to establish a vessel traffic service, using existing resources or otherwise; and

(B) whether an Arctic Response Center of Expertise is necessary to address the gaps in experience, skills, equipment, resources, training, and doctrine to prepare, respond to, and recover spilled oil in the Arctic; and

(7) an assessment of whether sufficient agreements are in place to ensure the Coast Guard is receiving the information it needs to carry out its responsibilities.

Conference

The conference report (H.Rept. 115-874 of July 25, 2018) on H.R. 5515/P.L. 115-232 of August 13, 2018, states the following:

Coast Guard Authorization Act of 2018

The House bill contained a division (Division D) that would authorize certain aspects of the Coast Guard.

The Senate amendment contained no similar provisions.

The House recedes. (Page 1137)

Appendix A. Planned NSC, OPC, and FRC Procurement Quantities

This appendix provides further discussion on the issue of the Coast Guard's planned NSC, OPC, and FRC procurement quantities.

Overview

The Coast Guard's program of record for NSCs, OPCs, and FRCs includes only about 61% as many cutters as the Coast Guard calculated in 2011 would be needed to fully perform its projected future missions. The Coast Guard's planned force levels for NSCs, OPCs, and FRCs have remained unchanged since 2004. In contrast, the Navy since 2004 has adjusted its ship force-level goals eight times in response to changing strategic and budgetary circumstances.44

Although the Coast Guard's strategic situation and resulting mission demands may not have changed as much as the Navy's have since 2004, the Coast Guard's budgetary circumstances may have changed since 2004. The 2004 program of record was heavily conditioned by Coast Guard expectations in 2004 about future funding levels in the PC&I account. Those expectations may now be different, as suggested by the willingness of Coast Guard officials in 2017 to begin regularly mentioning the need for an PC&I funding level of $2 billion per year (see Appendix B).

It can also be noted that continuing to, in effect, use the Coast Guard's 2004 expectations of future funding levels for the PC&I account as an implicit constraint on planned force levels for NSCs, OPCs, and FRCs can encourage an artificially narrow view of Congress's options regarding future Coast Guard force levels and associated funding levels, depriving Congress of agency in the exercise of its constitutional power to provide for the common defense and general welfare of the United States, and to set funding levels and determine the composition of federal spending.

2009 Coast Guard Fleet Mix Analysis

The Coast Guard estimated in 2009 that with the POR's planned force of 91 NSCs, OPCs, and FRCs, the service would have capability or capacity gaps45 in 6 of its 11 statutory missions—search and rescue (SAR); defense readiness; counterdrug operations; ports, waterways, and coastal security (PWCS); protection of living marine resources (LMR); and alien migrant interdiction operations (AMIO). The Coast Guard judges that some of these gaps would be "high risk" or "very high risk."

Public discussions of the POR frequently mention the substantial improvement that the POR force would represent over the legacy force. Only rarely, however, have these discussions explicitly acknowledged the extent to which the POR force would nevertheless be smaller in number than the force that would be required, by Coast Guard estimate, to fully perform the Coast Guard's statutory missions in coming years. Discussions that focus on the POR's improvement over the legacy force while omitting mention of the considerably larger number of cutters that would be required, by Coast Guard estimate, to fully perform the Coast Guard's statutory missions in coming years could encourage audiences to conclude, contrary to Coast Guard estimates, that the POR's planned force of 91 cutters would be capable of fully performing the Coast Guard's statutory missions in coming years.

In a study completed in December 2009 called the Fleet Mix Analysis (FMA) Phase 1, the Coast Guard calculated the size of the force that in its view would be needed to fully perform the service's statutory missions in coming years. The study refers to this larger force as the objective fleet mix. Table A-1 compares planned numbers of NSCs, OPCs, and FRCs in the POR to those in the objective fleet mix.

|

Ship type |

Program of Record (POR) |

Objective Fleet Mix From FMA Phase 1 |

Objective Fleet Mix compared to POR |

||

|

Number |

% |

||||

|

NSC |

8 |

9 |

+1 |

+13% |

|

|

OPC |

25 |

57 |

+32 |

+128% |

|

|

FRC |

58 |

91 |

+33 |

+57% |

|

|

Total |

91 |

157 |

+66 |

+73% |

|

Source: Fleet Mix Analysis Phase 1, Executive Summary, Table ES-8 on page ES-13.

As can be seen in Table A-1, the objective fleet mix includes 66 additional cutters, or about 73% more cutters than in the POR. Stated the other way around, the POR includes about 58% as many cutters as the 2009 FMA Phase I objective fleet mix.

As intermediate steps between the POR force and the objective fleet mix, FMA Phase 1 calculated three additional forces, called FMA-1, FMA-2, and FMA-3. (The objective fleet mix was then relabeled FMA-4.) Table A-2 compares the POR to FMAs 1 through 4.

|

Ship type |

Program of Record (POR) |

FMA-1 |

FMA-2 |

FMA-3 |

FMA-4 (Objective Fleet Mix) |

|

NSC |

8 |

9 |

9 |

9 |

9 |

|

OPC |

25 |

32 |

43 |

50 |

57 |

|

FRC |

58 |

63 |

75 |

80 |

91 |

|

Total |

91 |

104 |

127 |

139 |

157 |

Source: Fleet Mix Analysis Phase 1, Executive Summary, Table ES-8 on page ES-13.

FMA-1 was calculated to address the mission gaps that the Coast Guard judged to be "very high risk." FMA-2 was calculated to address both those gaps and additional gaps that the Coast Guard judged to be "high risk." FMA-3 was calculated to address all those gaps, plus gaps that the Coast Guard judged to be "medium risk." FMA-4—the objective fleet mix—was calculated to address all the foregoing gaps, plus the remaining gaps, which the Coast Guard judge to be "low risk" or "very low risk." Table A-3 shows the POR and FMAs 1 through 4 in terms of their mission performance gaps.

Table A-3. Force Mixes and Mission Performance Gaps

From Fleet Mix Analysis Phase 1 (2009)—an X mark indicates a mission performance gap

|

Missions with performance gaps |

Risk levels of these performance gaps |

Program of Record (POR) |

FMA-1 |

FMA-2 |

FMA-3 |

FMA-4 (Objective Fleet Mix) |

|

Search and Rescue (SAR) capability |

Very high |

X |

||||

|

Defense Readiness capacity |

Very high |

X |

||||

|

Counter Drug capacity |

Very high |

X |

||||

|

Ports, Waterways, and Coastal Security (PWCS) capacitya |

High |

X |

X |

|||

|

Living Marine Resources (LMR) capability and capacitya |

High |

X |

X |

[all gaps addressed] |

||

|

PWCS capacityb |

Medium |

X |

X |

X |

||

|

LMR capacityc |

Medium |

X |

X |

X |

||

|

Alien Migrant Interdiction Operations (AMIO) capacityd |

Low/very low |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

PWCS capacitye |

Low/very low |

X |

X |

X |

X |

Source: Fleet Mix Analysis Phase 1, Executive Summary, page ES-11 through ES-13.

Notes: In the first column, The Coast Guard uses capability as a qualitative term, to refer to the kinds of missions that can be performed, and capacity as a quantitative term, to refer to how much (i.e., to what scale or volume) a mission can be performed.