Introduction

The Generalized System of Preferences (GSP) provides nonreciprocal, duty-free tariff treatment to certain products imported into the United States from designated beneficiary developing countries (BDCs). The United States, the European Union (EU), and other developed countries have implemented similar programs since the 1970s in order to promote economic growth in developing nations.

Currently, 121 developing countries and territories are GSP beneficiary developing countries (BDCs). The GSP program provides duty-free entry into the United States for over 3,500 products (based on 8-digit U.S. Harmonized Tariff Schedule tariff lines) from BDCs, and duty-free status to an additional 1,500 products from 44 GSP beneficiaries additionally designated as least-developed beneficiary developing countries (LDBDCs). In 2017, products valued at about $21.2 billion (imports for consumption) entered the United States duty-free under the program, out of total imports from GSP countries of about $220 billion. Total U.S. imports from all countries amounted to about $2.3 trillion in 2017.

This report briefly summarizes recent GSP developments. It provides a brief history, economic rationale, legal background, and comparison of preferential trade programs worldwide and describes the U.S. implementation of the GSP program.

Latest Developments

On March 23, 2018, President Trump signed the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2018 (P.L. 115-141). Division M, Title V of the Act extended the GSP program until December 31, 2020. The program was also retroactively renewed for all GSP-eligible entries between December 31, 2017 (the previous expiration date), and April 22, 2018, the effective date of the current GSP renewal reauthorization. The GSP reauthorization also made certain technical modifications to competitive need limits and waivers, and required the U.S. Trade Representative (USTR) to submit an annual report to Congress on efforts to ensure that GSP countries are meeting the eligibility criteria for the program.

U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) will issue automatic refunds of duties paid during the GSP program lapse if (1) importer of record (IOR) information is current, (2) entries continued be flagged as GSP-eligible imports (with the special program indicator (SPI) "A,") during the program lapse, and (3) the importer is a member of CBP's Automated Clearinghouse (ACH) program. If the importer did not fulfill these criteria, a refund request may be submitted in a letter, as a post-summary correction (PSC), or as a protest. The request must include all importer of record (IOR) information; the import entry number, line number, and U.S. Harmonized Tariff Schedule (HTSUS) number; the amount of the estimated total refund; and a signed statement that the goods are eligible for GSP.1

Beneficiary

In Proclamation 9687 of December 22, 2017, President Trump reinstated Argentina's GSP eligibility.2 In the same proclamation, the President suspended Ukraine's GSP eligibility with respect to certain tariff lines because the country did not provide adequate protection of intellectual property rights (IPR).3

GSP-Eligible Products

According to the GSP statute, the President is authorized to designate additional products as duty-free under GSP, following a product review and analysis by the U.S. International Trade Commission (ITC). The ITC's role is primarily to determine if the products would be import-sensitive if imported duty-free from GSP beneficiaries.4

Congress, from time to time, provides the President with additional authority to declare duty-free access for particular goods. Section 202 of P.L. 114-27 gave the President the authority to amend the list of GSP-eligible products by designating certain cotton and cotton waste products as duty-free for eligible least-developed beneficiaries (see Table 1). According to the Senate report accompanying H.R. 1295, the provision was included to implement the U.S. commitments to the WTO to provide duty-free, quota-free treatment for certain cotton products originating from least-developed countries.5 President Obama implemented authority on June 30, 2016.6

Table 1. GSP-Eligible Cotton Products (Least-Developed Beneficiaries)

Pursuant to Section 503(b) of the Trade Act of 1974, as amended by Section 202 of P.L. 114-27

|

Harmonized Tariff Schedule Number |

Description |

Normal Trade Relations Tariff (if no GSP) |

|

5201.00.18 |

Cotton, not carded or combed; Harsh or rough, having a staple length under 19.05 mm (3/4 inch); Other |

31.4 cents per kilogram |

|

5201.00.28 |

Cotton, not carded or combed; other, harsh or rough, having a staple length of 29.36875 mm (1-5/32 inches) or more and white in color (except cotton of perished staple, grabbots and cotton pickings); Other |

31.4 cents per kilogram |

|

5201.00.38 |

Cotton, not carded or combed; having a staple length of 28.575 mm (1-1/8 inches) or more but under 34.925 mm (1-3/8 inches); Other |

31.4 cents per kilogram |

|

5202.99.30 |

Cotton waste (including yarn waste and garnetted stock); Other |

7.8 cents per kilogram |

|

5203.00.30 |

Cotton, carded or combed; fibers of cotton processed, but not spun; Other |

31.4 cents per kilogram |

Source: CRS table based on the Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the United States (HTSUS).

Notes: "Normal Trade Relations" (NTR) is the term used in U.S. law to describe the "most-favored-nation" principle" (MFN). MFN means that countries must treat imports from other trading partners on the same basis as that given to other nations. Based on Section 202 of P.L. 114-27, the President provided all least-developed GSP beneficiaries with duty-free access for the items above.

Section 204 of P.L. 114-27 also granted similar presidential authority to designate certain luggage and travel articles as eligible for GSP (See Table 2). After completion of the ITC analysis, the Obama Administration declared these goods eligible for duty-free treatment for GSP least-developed and African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) beneficiaries only.7

The American Apparel and Footwear Association (AAFA) and other associations in the travel goods industry, as well as several Members of Congress, reportedly asserted that travel goods should be eligible for duty-free treatment for all GSP beneficiaries.8 In a March 20, 2017, letter to President Trump, the AAFA requested that he provide GSP access accordingly.9 In Presidential Proclamation 9625, President Trump provided duty-free access for 23 luggage and travel goods specified in the law to all GSP beneficiaries.10

Table 2. GSP-Eligible Luggage and Travel Products

Pursuant to Section 503(b)(1) of the Trade Act of 1974, as amended by Section 204 of P.L. 114-27

|

Harmonized Tariff Schedule Number |

Description |

Normal Trade Relations Tariff (if no GSP) |

|

4202.11.00 |

Trunks, suitcases, vanity and all other cases, occupational luggage and like containers, surface of leather, composition or patent leather |

8% |

|

4202.12.21 |

Trunks, suitcases, vanity and attaché cases and similar containers, with outer surface of plastics |

20% |

|

4202.12.40 |

Trunks, suitcases, vanity & attaché cases, occupational luggage & like containers, surfaces of cotton, not of pile or tufted construction |

6.3% |

|

4202.12.81 |

Trunks, suitcases, vanity & attaché cases, occupational luggage and similar containers, with outer surface of man-made fiber (MMF) materials |

17.6% |

|

4202.21.60 |

Handbags, with or without shoulder strap or without handle, with outer surface of leather, composition or patent leather, not otherwise indicated, not over $20 each |

10% |

|

4202.21.90 |

Handbags, with or without shoulder strap or without handle, with outer surface of leather, composition or patent leather, not otherwise indicated, over $20 each |

9% |

|

4202.22.15 |

Handbags, with or without shoulder straps or without handle, with outer surface of sheeting of plastics |

16% |

|

4202.22.45 |

Handbags, with or without shoulder straps, including those without handle; with outer surface of cotton; not of pile or tufted construction or braid |

6.3% |

|

4204.22.81 |

Handbags with or without shoulder strap or without handle, with outer surface of MMF materials |

17.6% |

|

4202.31.60 |

Articles of a kind normally carried in the pocket or in the handbag; with outer surface of leather, composition, or patent leather, not otherwise indicated |

8% |

|

4202.32.40 |

Articles of a kind normally carried in the pocket or in the handbag; with outer surface of textile materials; of cotton and not of pile or tufted construction |

6.3% |

|

4202.32.80 |

Articles of a kind normally carried in the pocket or in the handbag; with outer surface of textile materials; of vegetable fibers and not of pile or tufted construction; excluding cotton |

5.7% |

|

4202.32.93 |

Articles of a kind normally carried in the pocket or handbag, with outer surface of MMF |

6.3% |

|

4202.32.99 |

Articles of a kind normally carried in the pocket or handbag, with outer surface of other textile materials |

17.6% |

|

4202.91.90 |

Cases, bags and containers not otherwise indicated, other than golf bags, with outer surface of leather, of composition leather |

4.5% |

|

4202.92.15 |

Travel, sports and similar bags with outer surface of cotton, not of pile or tufted construction |

6.3% |

|

4202.92.20 |

Travel, sports, and similar bags; with outer surface of textile materials; of vegetable fibers excluding cotton, and not of pile or tufted construction |

5.7% |

|

4202.92.31 |

Travel, sports and similar bags with outer surface of MMF textile material |

17.6% |

|

4202.92.39 |

Travel, sports and similar bags with outer surface of textile materials other than MMF, paper yarn, silk, cotton |

17.6% |

|

4202.92.45 |

Travel, sports, and similar bags with outer surface of plastic sheeting |

20% |

|

4202.92.91 |

Bags, cases and similar containers with outer surface of textile materials, of MMF except jewelry boxes |

17.6% |

|

4202.92.97 |

Bags, cases & similar containers with outer surface of sheeting of plastic materials, not containers for CDs or cassettes, or CD or cassette players |

17.6% |

|

4202.99.90 |

Cases, bags, and similar containers, not otherwise indicated, with outer surface of vulcanized fiber or of paperboard |

20% |

|

4202.11.00 |

Trunks, suitcases, vanity and all other cases, occupational luggage and like containers, surface of leather, composition or patent leather |

8% |

|

4202.12.21 |

Trunks, suitcases, vanity and attache cases and similar containers, with outer surface of plastics |

20% |

Source: CRS table based on Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the United States (HTSUS) and USTR documents.

Notes: Normal Trade Relations" (NTR) is the term used in U.S. law to describe the "most-favored-nation" principle" (MFN). MFN means that countries must treat imports from other trading partners on the same basis as that given to other nations.

Based on Section 204 of P.L. 114-27, the President provided duty-free access for these products to all GSP beneficiaries, in Proclamation 9625 of June 29, 2017. The HTSUS subheadings in the law are not the same as those provided above due to subsequent HTSUS modifications made in Proclamation 9466 of June 30, 2016.

History, Rationale, and Comparison of GSP Programs

The basic principle behind GSP trade programs worldwide is to provide developing countries with unilateral preferential market access to developed-country markets in order to spur economic growth in poorer countries. The preferential access is in the form of lower tariff rates (or as in the U.S. case, duty-free status) for certain products that are determined not to be "import sensitive" in the receiving country market. The program concept was first adopted internationally in 1968 by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) at the UNCTAD II Conference.11

Economic and Political Basis

The GSP concept and programs were established based on the premise that preferential tariff rates in developed country markets could promote export-driven industry growth in developing countries. It was believed that this, in turn, would help to free beneficiaries from heavy dependence on trade in primary products (e.g., raw materials), and help diversify their economies to promote stable growth.12

Some economists claim that GSP was established, in part, as a means of reconciling two widely divergent economic perspectives of trade equity that arose during early negotiations on the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT).13 Industrialized, developed nations argued that the most-favored-nation (MFN) principle14 should be the fundamental and universal principle governing multilateral trade, while less-developed countries believed that equal treatment of economically unequal trading partners did not constitute equity in trade benefits. These countries called for "special and differential treatment" for developing countries. Economists assert that GSP schemes thus became one of the means of offering a form of special treatment that developing nations sought, while allaying the fears of developed countries that tariff "disarmament" might create serious disruptions among import-sensitive industries in their domestic markets.15

Due to differences in developed countries' economic structures and tariff programs—as well as differences in the types of domestic industries and products each country wanted to shield from greater foreign competition—it proved difficult to create one unified system of tariff concessions on additional products. Therefore, the GSP concept became a system of individual national schemes based on common goals and principles—each with a view toward providing developing countries with generally equivalent opportunities for export growth.16 As a result, the preference-granting countries implemented various individual schemes of temporary, generalized, nonreciprocal preferences under which tariffs were lowered or eliminated on some imports from certain developing countries.

Although not specifically allowed or codified in the GATT, the programs of most GSP-granting countries place certain conditions on the nonreciprocal preferences by (1) excluding certain countries; (2) determining specific product coverage; (3) determining rules of origin governing the preference; (4) determining the duration of the scheme; (5) reducing preferential margins accruing to developing countries by continuing to lower or remove tariffs as a result of multilateral, bilateral, and regional negotiations; (6) preventing the concentration of benefits among a few countries; (7) including safeguard mechanisms or "escape" clauses to protect import-sensitive industries; and (8) placing caps on the volume of duty-free trade entering under their programs.17

GATT/World Trade Organization Framework

By its very nature as a trade preference, the GSP concept posed a problem under the GATT, because granting preferences to particular countries is inconsistent with the fundamental nondiscrimination obligation placed on GATT Parties (GATT Article I:1) to grant MFN tariff treatment to the products of all other GATT Parties. However, since preference programs were viewed as a means of transitioning developing countries to greater trade liberalization and economic development, GATT Parties accommodated them in a series of joint actions.

First, in 1965, the GATT Parties added Part IV to the General Agreement, an amendment that recognizes the special economic needs of developing countries and asserts the principle of non-reciprocity. Under this principle, developed countries may forego the receipt of reciprocal benefits for their negotiated commitments to reduce or eliminate tariffs and restrictions on the trade of less developed contracting parties.18 Second, because of the underlying MFN issue, GATT Parties in 1971 adopted a waiver of Article I for GSP programs to allow developed contracting parties to accord more favorable tariff treatment to the products of developing countries for 10 years.19 The GSP was described in the decision as a "system of generalized, non-reciprocal and non-discriminatory preferences beneficial to the developing countries."

Enabling Clause

At the end of the Tokyo Round of Multilateral Trade Negotiations in 1979, developing countries secured adoption of the so-called Enabling Clause, a permanent deviation from MFN by joint decision of the GATT Contracting Parties.20 The clause states that notwithstanding GATT Article I, "contracting parties may accord differential and more favorable treatment to developing countries, without according such treatment to other contracting parties," and applies this exception to the following:

(a) Preferential tariff treatment accorded by developed contracting parties to products originating in developing countries in accordance with the Generalized System of Preferences;

(b) Differential and more favorable treatment with respect to the provisions of the General Agreement concerning non-tariff measures governed by the provisions of instruments multilaterally negotiated under the auspices of the GATT;

(c) Regional or global arrangements entered into amongst less-developed contracting parties for the mutual reductions or elimination of tariffs and, in accordance with criteria or conditions which may be prescribed by the contracting parties for the mutual reduction or elimination of non-tariff measures, on products imported from one another;

(d) Special treatment on the least developed among the developing countries in the context of any general or specific measures in favour of developing countries.

Additional Commitment to Least Developed Countries

When launching the Doha Development Agenda (DDA) negotiations in November 2001, World Trade Organization (WTO, successor to the GATT established in 1995) members committed themselves to provide "duty free/quota free" (DFQF) access to the products of least-developed countries in keeping with the shared objective of the international community as expressed in the Millennium Development Goals.21 During DDA negotiations at the sixth WTO Ministerial Conference in Hong Kong in December 2005, developed country WTO members and "developing country members declaring themselves in a position to do so" agreed to deepen this commitment by providing DFQF access to at least 97% of products originating from Least Developed Countries (LDCs) by 2008, "in a manner that ensures stability, security and predictability."22 Many developed countries continued to implement these provisions despite the failure of the DDA. As of October 2015, most developed countries granted either full or near full access to LDCs, and several developing countries had also taken concrete steps to provide duty-free access to products from LDCs.23

Comparison of International GSP Programs

Other developed countries besides the United States that implement GSP programs include Australia, Canada, the EU, Iceland, Japan, New Zealand, Norway, the Russian Federation, Switzerland, and Turkey.24 One economist has referred to these programs as a nonhomogeneous set of national schemes sharing certain common characteristics.25 Generally, each preference-granting country extends to qualifying developing countries (as determined by each benefactor) an exemption from duties (reduced tariffs or duty-free access) on most manufactured products and certain "non-sensitive" agricultural products. Product coverage and the type of preferential treatment offered varies widely.26

In the WTO, the developing country status of members is generally based on self-determination. For GSP, however, each preference-granting country establishes particular criteria and conditions for defining and identifying developing country beneficiaries. Consequently, the list of beneficiaries and exceptions may vary greatly among countries. If political or economic changes have taken place in a beneficiary country, it might be excluded from GSP programs in some countries but not in others. Some countries, including the United States, also reserve the right to exclude countries if they have entered into another kind of commercial arrangement (e.g., a free trade agreement) with any other GSP-granting developed country, and in the U.S. case, "if it has, or is likely to have, a significant adverse effect on United States commerce."27

In terms of additional GSP product coverage for LDCs, the EU's program, which offers duty-free access for "Everything but Arms,"28 is currently perhaps the most inclusive. GSP-granting countries may also have incentive-based programs that provide enhanced benefits for beneficiary countries that meet certain additional criteria. In 2007, for example, the EU implemented a regulation that grants additional GSP benefits to countries that have demonstrated their commitment to sustainable development and internationally recognized worker rights.29

Each preference-granting nation also has safeguards in place to ensure that any significant increases in imports of a certain product do not adversely affect the receiving country's domestic market. Generally, these restrictions take the form of quantitative limits on goods entering under GSP. Under Japan's system, for example, imports of certain products under the preference are limited by quantity or value (whichever is applicable) on a first-come, first-served basis administered monthly (or daily, if indicated). For other products, import ceilings and maximum country amounts are set by prior allotment.30 The United States quantitatively limits imports under the GSP program by placing "competitive need limit" (CNL) thresholds on the quantity or value of commodities entering duty-free, as discussed in more detail below.

Each GSP benefactor also has criteria for graduation—the point at which beneficiaries no longer qualify for benefits because they have reached a certain level of development. Most preference-granting countries require mandatory graduation based on a certain level of income per capita based on World Bank calculations. Some programs, such as the EU's, also specifically provide for graduation of certain GSP recipients with respect to specific product sectors. A description of three other countries' GSP programs follows.

EU Generalised Scheme of Preferences

The EU Generalised Scheme of Preferences has three different preference arrangements:

- The "Standard" GSP framework grants duty reductions for about 66% of all EU tariff lines, to low-income or middle-income countries that do not benefit from any other preferential trade access to the EU market. In the 2016-2017 period, there were 23 Standard GSP beneficiaries.31

- The Sustainable Development and Good Governance (GSP+) grants duty-free access to the same 66% of EU tariff lines as Standard GSP to beneficiaries that are found to be especially vulnerable in terms of economic diversification and import volumes. In return, these countries must ratify and effectively implement 27 core international conventions, human and labor rights, environmental protection, and good governance.32 During the 2016-2017 period, there were 10 GSP+ beneficiary countries.

- The Everything but Arms (EBA) arrangement grants full-duty-free, quota-free access for all products except arms and ammunition for all United Nations-classified least-developed countries. In 2016-2017, there were 49 EBA beneficiaries.33

EU GSP Changes in 2014

On January 1, 2014, the EU implemented substantial changes to its Generalised Scheme of Preferences (EU GSP) program that it stated were intended to (1) better focus on countries in need; (2) further promote core principles of sustainable development and good governance; and (3) enhance stability and predictability.34 As part of the changes, the EU mandatorily graduated all countries identified by the World Bank as upper-middle income and above, as well as excluding those countries that benefit from a preferential market access arrangement with the EU. To add a measure of stability to the program, the EU extended GSP benefits for 10 years, and provided transition periods of at least one year for those countries that will lose EU GSP eligibility. Currently, there are 23 beneficiaries of the standard EU GSP program, 10 beneficiaries of the "GSP+" program, and 49 beneficiaries in the GSP "Everything But Arms" (EBA) program.35

Economic Partnership Agreements

Since 2000, As part of a long-term overhaul of the EU's relationship of its trade arrangements with developing countries, including its GSP beneficiaries, negotiations have been ongoing to establish reciprocal, WTO-compliant "Economic Partnership Agreements" (EPAs) with developing country trading partners in the African, Caribbean, and Pacific regions. The most recent countries to sign on to EPAs were, The Gambia (August 2018) and Mauritania (September 2018).36

Canada's General Preferential Tariff (GPT)

Canada's General Preferential Tariff (GPT), first implemented in 1974, provides duty-free or reduced tariff rates for designated developing country beneficiaries. The GPT program expires, and is reviewed and amended on a 10-year cycle. Canada's Economic Action Plan for 2012 announced a comprehensive review of the GPT in advance of its expiration in June 30, 2014, due to "significant shifts the income levels and trade competitiveness of certain developing countries" since 1974, and to ensure that the GPT is "aligned with Canada's development policy objectives."37 As a result of the review, Canada withdrew GPT benefits from 72 countries, but continues to extend preferential treatment to 103 beneficiaries, 48 of which also benefit from Canada's Least Developed Country Tariff (LDCT).38 Canada announced that it would continue to review the list of beneficiary countries biannually, and will automatically graduate countries that are either classified for two consecutive years as high or upper middle income countries; or have a 1% or greater share of world exports for two consecutive years.39 Canada's GPT is currently authorized until December 31, 2024.

Japan's Generalized System of Preferences

Japan's GSP program, first implemented in 1971, provides preferential tariff treatment to 138 developing countries and 5 territories. Beneficiaries are designated on the basis of (1) being in the stage of development, (2) having its own trade and tariff system, (3) its desire to receive preferential tariff treatment, and (4) a determination by Cabinet Order that the beneficiary is a country or territory to which such preferences may be extended.40

Reduced or duty-free status is provided for 408 products in the agricultural and fisheries sectors (Harmonized System (HS) chapters 1-24), and for 3,151 industrial/manufactured products (HS chapters 25-97). Most industrial products are duty-free to GSP beneficiaries, but tariff reductions are provided on some import sensitive items.41 Countries recognized as least-developed countries by the United Nations receive duty-free, quota-free market access for the above products, as well as for additional items.42

A country or territory may be partially graduated from Japan's GSP scheme if it is classified as a high-income country in World Bank statistics in the previous year, or is classified as an upper-middle income country and the value of the beneficiary's exports exceeds 1% of the total value of world exports in the previous year. 43 Countries are permanently graduated from GSP if they are classified as by the World Bank as a high-income economy for three consecutive years.

Beneficiaries may also lose GSP benefits for certain products if, for the past three years, regarding Japanese exports of that product: (1) the average value of Japan's imports of the product originating from the beneficiary for the past three years exceeds 1.5 billion yen and 50% of the world's exports of the product to Japan, or (2) in the case of any fish product, the country or territory is judged (by a Regional Fisheries Management Organization) to be against the conservation of certain fish species.44

United States GSP Implementation

Congress first authorized the U.S. Generalized System of Preferences scheme in Title V of the Trade Act of 1974 (P.L. 93-618), as amended.45 P.L. 93-618 gave the President the authority to grant duty-free treatment under the GSP for eligible products imported from any beneficiary developing country (BDC) or any least-developed beneficiary developing country (LDBDC), provided the President with economic criteria in deciding whether to take any such action, and specified certain other criteria for designating eligible countries and products.46

GSP country eligibility changes or changes in product coverage are made at the discretion of the President, drawing on the advice of the ITC and the USTR. The TPSC, an executive branch interagency body chaired by the office of the USTR, serves as the interagency policy coordination mechanism for matters involving GSP.47 The GSP Subcommittee48 of the TPSC conducts an annual review in which petitions related to GSP country and product eligibility are assessed, and makes recommendations to the full TPSC, which, in turn, passes these recommendations to the USTR.

Country Eligibility Criteria

When designating BDCs and LDBDCs, the President is directed to take into account certain mandatory and discretionary criteria. The law prohibits (with certain exceptions) the President from extending GSP treatment to certain countries, as follows:49

- other industrialized countries (Australia, Canada, EU member states, Iceland, Japan, Monaco, New Zealand, Norway, and Switzerland are specifically excluded);

- communist countries, unless they are a WTO member, a member of the International Monetary Fund, and receive Normal Trade Relations (NTR) treatment from the United States; must also not be "dominated or controlled by international communism";

- countries that collude with other countries to withhold supplies or resources from international trade or raise the price of goods in a way that could cause serious disruption to the world economy;

- countries that provide preferential treatment to the products of another developed country in a manner likely to have a significant adverse impact on U.S. commerce;

- countries that have nationalized or expropriated the property of U.S. citizens (including corporations, partnerships, or associations that are 50% or more beneficially owned by U.S. citizens), or otherwise infringe on U.S. citizens' intellectual property rights (IPR), including patents, trademarks, or copyrights;

- countries that have taken steps to repudiate or nullify existing contracts or agreements of U.S. citizens (or corporations, partnerships, or associations that are 50% or more owned by U.S. citizens) in a way that would nationalize or seize ownership or control of the property, including patents, trademarks, or copyrights;

- countries that have imposed or enforced taxes or other restrictive conditions or measures on the property of U.S. citizens; unless the President determines that compensation is being made, good faith negotiations are in progress, or a dispute has been handed over to arbitration in the Convention for the Settlement of Investment Disputes or another forum;

- countries that have failed to act in good faith to recognize as binding or enforce arbitral awards in favor of U.S. citizens (or corporations, partnerships, or associations that are 50% or more owned by U.S. citizens); and

- countries that grant sanctuary from prosecution to any individual or group that has committed an act of international terrorism, or have not taken steps to support U.S. efforts against terrorism.

Mandatory criteria also require that beneficiary countries

- have taken or are taking steps to grant internationally recognized worker rights (including collective bargaining, freedom from compulsory labor, minimum age for employment of children, and acceptable working conditions with respect to minimum wages, hours of work, and occupational safety and health); and

- implement their commitments to eliminate the worst forms of child labor.50

The President has the authority to waive certain mandatory criteria if he determines that GSP designation of any country is in the national economic interest of the United States and reports this determination to Congress.51

The President is also directed to consider certain discretionary criteria, or "factors affecting country designation":

- a country's expressed desire to be designated a beneficiary developing country for purposes of the U.S. program;

- the level of economic development of a country;

- whether or not other developed countries are extending similar preferential tariff treatment to a country;

- a country is committed to providing reasonable and equitable access to its market and basic commodity resources, and the extent to which a country has assured the United States that it will not engage in unreasonable export practices;

- the extent to which a country provides adequate protection of intellectual property rights;

- the extent to which a country has taken action to reduce trade-distorting investment policies and practices, and to reduce or eliminate barriers to trade in services; and

- whether or not a country has taken steps to grant internationally recognized worker rights.52

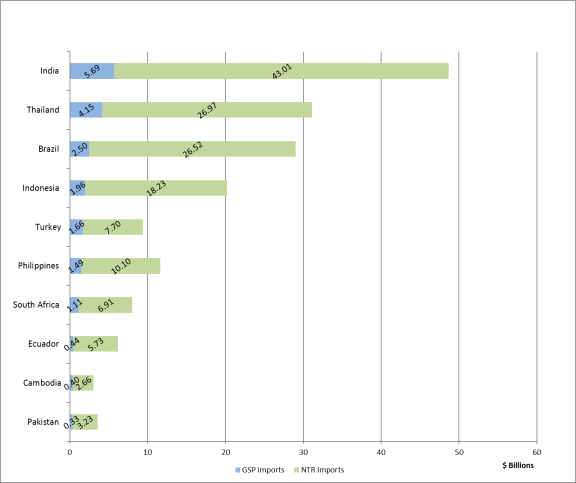

The law further authorizes the President, based on the required and discretionary factors mentioned above, to withdraw, suspend, or limit GSP treatment for any beneficiary developing country at any time (see Table B-1 for a list of currently eligible GSP beneficiaries). Figure 1 shows the GSP duty-free imports of the top 10 BDCs as a proportion of their total imports to the United States in 2017.53

Least-Developed Beneficiaries

The President is authorized by statute to designate any BDC as a LDBDC, based on an assessment of the conditions and factors previously mentioned.54 Although the United Nations' designation of LDCs plays a large factor in GSP least-developed beneficiary determinations,55 U.S. officials may also assess compliance with GSP statutory requirements and comments from the public (as requested in the Federal Register) before identifying a country as "least-developed" for purposes of the GSP.56

Country Graduation from GSP

The President may withdraw, suspend, or limit the GSP status of a BDC if he determines that a country is determined to be sufficiently competitive or developed. In 2014, President Obama removed Russia's GSP eligibility for this reason.57 Mandatory country graduation occurs when the BDC is determined to be a "high income country" as defined by official World Bank statistics (gross national income [GNI] per capita of $12,055 or more in 2016).58 On September 30, 2015, the President determined that Seychelles, Uruguay, and Venezuela had become "high income" countries, and therefore, no longer eligible for GSP benefits, effective January 1, 2017.59

If a country becomes part of an association of countries specifically excluded from GSP, the country is mandatorily withdrawn from GSP. Bulgaria and Romania were the last countries to lose GSP eligibility for this reason, effective when they became EU member states as of January 1, 2007.60 Although not specifically required by the GSP statute, a developing country that enters into a free trade agreement (FTA) with the United States, at the discretion of Congress, generally loses GSP eligibility in favor of the reciprocal concessions granted by the FTA. Specific language to this effect appears in FTA implementing legislation.61

Countries Recently Granted GSP Eligibility

On December 22, 2017, President Trump reinstated Argentina's GSP eligibility.62

On September 14, 2016, President Obama announced that Burma was eligible for GSP and also designated it a least-developed beneficiary. The action ended a 27-year suspension of Burma's GSP benefits due to worker rights violations.63 The reinstatement followed an extensive review of Burma's compliance with GSP eligibility criteria that had been ongoing since Burma's government first requested GSP reinstatement in 2013.64 Burma's eligibility status became official on November 14, 2016, following a 60-day congressional notification period.65 The review of Burma's GSP eligibility was just one part of a comprehensive review of the bilateral relationship in the wake of Burma's return to democratic governance.

Presidential Reporting Requirements

The President must advise Congress of any changes in beneficiary developing country and product status, as necessary.66 Additional GSP reporting requirements include an annual report to Congress on the status of internationally recognized worker rights within each BDC, including findings of the Secretary of Labor with respect to the beneficiary country's implementation of its international commitments to eliminate the worst forms of child labor.67

Eligible Products

The Trade Act of 1974 authorizes the President to designate certain imports as eligible for duty-free treatment under the GSP after receiving advice from the United States International Trade Commission (ITC).68 "Import sensitive" products specifically excluded from preferential treatment include most textiles and apparel goods; watches; footwear and other accessories; most electronics, steel, and glass products; and certain agricultural products that are subject to tariff-rate quotas.69

GSP Rules of Origin

Eligible goods under the U.S. GSP program must meet certain rules of origin (ROO) requirements in order to qualify for duty-free treatment. First, duty-free entry is only allowed if the article is imported directly from the beneficiary country into the United States without entering the commerce of a third country. Second, at least 35% of the appraised value of the product must be the "growth, product, or manufacture" of a beneficiary developing country, as defined by the sum of (1) the cost or value of materials produced in the BDC (or any two or more BDCs that are members of the same association or countries and are treated as one country for purposes of the U.S. law), plus (2) the direct costs of processing in the country.70

GSP Product Coverage

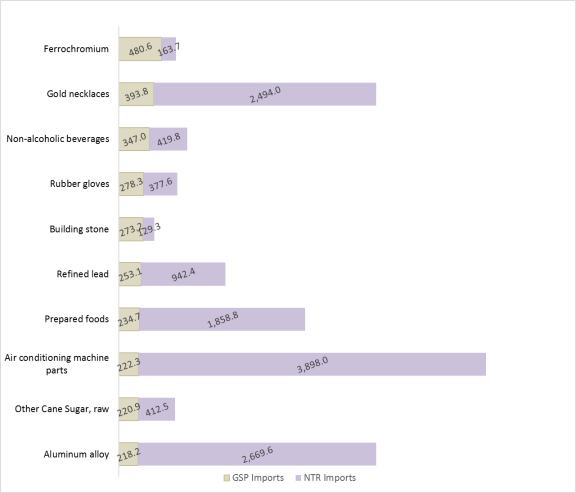

More than 3,500 products71 are currently eligible for duty-free treatment, and about 1,500 additional products originating in LDBDCs may receive similar preferential treatment. Table 3 provides leading products imported under GSP from all countries in 2017, including the Harmonized Tariff Schedule (HTS) subheading and description, along with the tariff that would have been assessed if the product had been imported under NTR tariff rates. Figure 2 shows the Top 10 U.S. GSP imports in 2017 as a proportion of U.S. total NTR trade for those products.

|

HTS Number |

NTR Tariff Rate (If No GSP) |

HTS Description |

GSP Imports (millions U.S. $) |

|

72024100 |

1.9% |

Ferrochromium containing by weight more than 4 percent of carbon |

$480.6 |

|

71131929 |

5.5% |

Gold necklaces and neck chains (other than of rope or mixed links) |

$393.8 |

|

22029990 |

$0.2 cents per liter |

Nonalcoholic beverages, not otherwise indicated, not including fruit or vegetable juices of heading 2009 |

$347.0 |

|

40151910 |

3.0% |

Seamless gloves of vulcanized rubber other than hard rubber, other than surgical or medical gloves |

$278.3 |

|

68029900 |

6.5% |

Monumental or building stone and articles thereof, not otherwise specified or indicated, further worked than simply cut/sawn, not otherwise specified or indicated. |

$273.2 |

|

78011000 |

2.5% on the value of the lead content |

Refined lead, unwrought |

$253.1 |

|

21069098 |

6.4% |

Other food preparations not otherwise specified or indicated, including preparations for the manufacture of beverages, non-dairy coffee whiteners, herbal teas and flavored honey |

$234.8 |

|

84159080 |

1.0% |

Parts for air conditioning machines, not otherwise specified or indicated |

$222.3 |

|

17011410 |

between $1.4606 cents per kg and $0.943854 cents per kg based on quality |

Other cane sugar, raw, in solid form, w/o added flavoring or coloring |

$220.9 |

|

76061230 |

3.0% |

Aluminum alloy, plates, sheets, or strip, with thickness over 0.2mm, rectangular (including square), not clad |

$218.2 |

|

71131950 |

5.5% |

Precious metal (other than silver) articles of jewelry and parts thereof, whether or not plated or clad with precious metal, not otherwise specified or indicated |

$216.4 |

|

87089475 |

2.5% |

Parts and accessories of motor vehicles of HTS 8701, not otherwise specified or indicated, and 8702-8705, parts of steering wheels/columns/boxes, not otherwise specified or indicated. |

$193.0 |

|

40111010 |

4.0% |

New pneumatic radial tires, of rubber, of a kind used on motor cars (including station wagons and racing cars) |

$187.7 |

|

40112010 |

4.0% |

New pneumatic radial tires, of rubber, of a kind used on buses or trucks |

$181.7 |

|

73239300 |

2.0% |

Stainless steel, table, kitchen, or household articles and parts thereof |

$169.8 |

Annual Reviews

The TPSC's GSP Subcommittee reviews and revises the lists of eligible products annually, generally on the basis of petitions received from beneficiary countries or interested parties requesting that additional products be reviewed (i.e., added or removed) for GSP eligibility.72 When a country's petition for product eligibility is approved, the product becomes GSP-eligible for all BDCs (or only for LDBDCs if so designated).73

The GSP Subcommittee also annually reviews issues regarding BDCs' and LDBDCs' observance of country practices (such as worker rights or IPR protection); investigates petitions to add or remove items from the list of eligible products; and considers which products should be removed on the basis that they are "sufficiently competitive," or are "import sensitive" relative to U.S. domestic firms.74

The GSP Subcommittee, after consultations with the ITC, also makes recommendations to the President regarding various product waivers that BDCs may have requested. Waiver petitions, if granted, are country-specific. Any modifications to product lists usually take effect on July 1 of the calendar year after the next annual review is launched, but may also be announced and become effective at other times of the year. At the completion of an annual review, the results are announced by proclamation.

Competitive Need Limits (CNL)

The GSP statute establishes "competitive need limit" (CNL) requirements for the President to suspend GSP treatment for individual products from BDCs (LDBDCs and AGOA countries are exempt) if

- imports of a product from a single country reach a specified threshold value, which increases by $5 million each calendar year (i.e., $175 million in 2016 and $180 million in 2017); or

- 50% or more of total U.S. imports of a product entering under GSP come from a single country.75

P.L. 115-141 amended the date that products that exceed the CNL become GSP-ineligible from GSP to November 1 of the next calendar year rather than July 1.76

CNL Waivers

BDCs may petition for CNL waivers, which the President reviews on a case-by-case basis. In deciding whether to grant a waiver, the President must (1) receive advice from the ITC as to whether a U.S. domestic industry could be adversely affected by the waiver; (2) determine that the waiver is in the U.S. economic interest; and (3) publish the determination in the Federal Register.77 The President is also required to give "great weight" to the extent to which the BDC opens its markets to the United States and protects IPR.78

In 2006, Congress amended the GSP law to provide that the President should revoke any CNL waiver that had been in effect for five years or more if (1) the exports of the product were in excess of 1.5 times of the specified dollar amount reflected in the CNL provision; or (2) imports of the product exceeded 75% of the appraised value of total imports of the product into the United States in a calendar year.79

After the latest GSP review, in Proclamation 9625 of June 29, 2017, the President determined to grant CNL waivers on certain coniferous lumber from Brazil.80

De Minimis Waivers

De minimis waivers may also be provided if the total dollar value of a particular product imported into the United States from all countries is small. The de minimis level is adjusted each year, in increments of $500,000; for example, $23.0 million in 2016, $23.5 million in 2017, and $24 million in 2018.81

In Proclamation 9625, the President granted 78 de minimis waivers to products from beneficiary countries including Brazil, India, Indonesia, Thailand, and Papua New Guinea.82 Products eligible for de minimis waivers included various agricultural products (e.g., papayas, mangoes, durians, tamarinds, and pistachios), chemical products (e.g., barium chloride, chromium sulfate), and animal hides and skins.83

Waivers for Articles not Produced in the United States (NPUS)

Prior to the enactment of the most recent GSP renewal, certain products that the President determined were not produced in the United States on January 1, 1995, were eligible for waivers of competitive need limits. Division M, Section 502 of P.L. 115-141 recently amended the statute to provide that BDCs could apply for waivers for certain products that were not produced in the United States for three years prior to the waiver request. Interested parties may petition for a waiver during the annual review process.84

Reviews of Country Practices

In the context of GSP annual reviews, any interested party may file a request that the GSP eligibility of any current GSP beneficiary be reviewed. For example, the GSP review of India announced in April 2018, in addition to the TPSC initiation mentioned above, was also based on market access petitions from three U.S. industry associations alleging that India did not provide equitable and reasonable access to its market. The eligibility review of Kazakhstan is based on a petition from the American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO) alleging that its government restricts the right to form trade unions and other internationally recognized worker rights.85 A new country practice review of Thailand was also announced on May 30, 2018 on the basis of a petition from the National Pork Producer's Council alleging that it is not meeting the GSP eligibility criterion to provide equitable and reasonable market access.86

In addition, in October 2017, USTR Lighthizer announced a new "proactive" process for ensuring that GSP beneficiaries are complying with the program's eligibility criteria. The process will include increased efforts to conclude outstanding country practices reviews, and a triennial assessment of each beneficiary's compliance with the statutory GSP eligibility criteria. The first assessment period will focus on Asian BDCs. GSP countries in other areas of the world will be assessed in the second and third years of the process. If the TPSC review raises concerns about a BDC's compliance, it may self-initiate a country practice review of the country's continued GSP eligibility.87 New country practice reviews of India, Indonesia, and Turkey initiated in 2018 were, in part, self-initiated by the TPSC due to this compliance review strategy.88

On October 15, 2018, the U.S. Trade Representative (USTR) announced a hearing of GSP beneficiaries for ongoing reviews of specific country practices. USTR targeted Bolivia (worker rights), Ecuador (arbitral awards), Georgia (worker rights), Indonesia (intellectual property rights), Iraq (worker rights), Thailand (worker rights), Ukraine (intellectual property rights), and Uzbekistan (worker rights and intellectual property rights).89 In addition, the hearing notice announced that it would include discussions on the ongoing country designation review for Laos.90 The hearing was held on November 29, 2018. The country practice reviews and the country designation review of Laos are currently ongoing.91

On August 16, 2018, the USTR announced the initiation of a GSP country practice review of Turkey focusing on the requirement of a GSP beneficiary to "assure the United States that it will provide equitable and reasonable access to its market." A hearing was held on September 26, 2018, and the review is ongoing.92

On October 15, 2018, the USTR announced a hearing on ongoing country practice reviews of Bolivia (worker rights), Ecuador (arbitral awards), Georgia (worker rights), Indonesia (intellectual property rights), Iraq (worker rights), Thailand (worker rights), Ukraine (intellectual property rights), and Uzbekistan (worker rights and intellectual property rights).93 In addition, the notice announced a hearing on an ongoing country designation review for Laos.94

Effects of the U.S. GSP Program

The statutory goals of the U.S. GSP program are to (1) promote the development of developing countries; (2) promote trade, rather than aid, as a more efficient way of promoting economic development; (3) stimulate U.S. exports in developing country markets; and (4) promote trade liberalization in developing countries.95 It is difficult to assess whether or not the program alone has achieved these goals, however, because the GSP is only one of many such initiatives used by the United States to assist poorer countries. Economic success within countries is also related to internal factors, such as governance, stability, wise policy decisions, availability of infrastructure to foster industry, and legal/financial frameworks that encourage foreign investment. External macroeconomic factors, including global economic growth, worldwide economic shocks, exchange rates, and regional stability may also influence the growth of developing countries.

What follows, therefore, are general comments, rather than hard data, about the impact of GSP on developing countries, and possible economic effects on the U.S. market. The positions of various stakeholders regarding the value of the program are also discussed.

Effects on Developing Countries

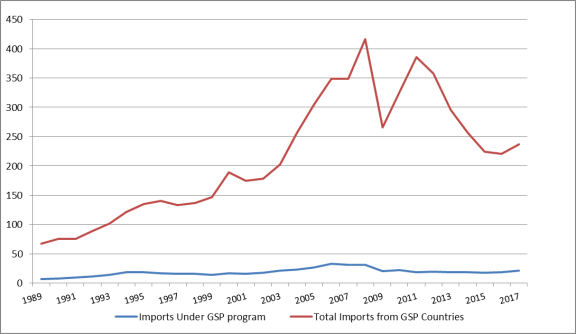

From 2000 to 2008, total U.S. imports from all GSP countries (see Figure 3, red line, includes imports entering the United States without preferential tariff treatment) increased dramatically by value, from $172 billion in 2000 to a peak of $384 billion in 2008. In 2009, imports from GSP countries decreased by 36% (to $246 billion) in 2009, largely due to the effects of the global economic downturn. Total imports increased to $367 billion in 2011, but decreased gradually to $238 billion in 2014, $207 billion in 2015, $202 billion in 2016. In 2017, total imports from all GSP countries increased to $215 billion (up 7%). The overall decline in total imports from GSP-eligible countries from 2012 to 2016 could be due to an overall reduction in commodity prices, 96 combined with geopolitical tensions, tightening of financial conditions, and political instability in some countries.97

Imports entering under the GSP program (see Figure 3, blue line, represents only imported products that qualify for GSP duty-free treatment) seem to have been relatively static, averaging about 11% of all imports from GSP countries.98 A number of factors could explain this, including uncertainty based on short-term GSP program renewals and long pauses between program authorization periods. Other programmatic factors that could keep GSP imports fairly constant over time include suspension, termination, or graduation of some countries from GSP eligibility; exclusion of certain products from eligibility through CNLs; and the entry of some developing countries (many of which had been GSP beneficiaries) entering into FTAs with the United States and thus being disqualified from GSP eligibility. In addition, some products from BDCs under the GSP program may receive more favorable treatment under other trade preference programs, such as AGOA or the Caribbean Basin Initiative (CBI).99

|

Figure 3. U.S. Imports from GSP Countries 2000-2017, current dollars |

|

|

Source: United States International Trade Commission Trade Dataweb. |

Many developing countries with a natural competitive advantage in certain products use trade preferences such as the GSP to gain a foothold in the international market. For example, India and Thailand, two countries with well-established jewelry industries, were able to expand their international reach through GSP programs. As the jewelry products reached their CNL thresholds, those countries were no longer eligible to receive duty-free status for their jewelry products under GSP, but gained a foothold in the U.S. and international markets that enabled their jewelry industries to continue to be competitive.100

However, some developing countries could also be encouraged by preferential trade programs to develop industry sectors in which they might not otherwise ever be able to compete, thus diverting resources from other industries that might stand a better chance of becoming competitive over time (trade diversion).101

Some economists assert that the lack of reciprocity in the GSP program could result in long-term costs for beneficiary countries, because by not engaging in multilateral, reciprocal negotiations in favor of preference programs, developing countries keep in place protectionist trade policies that could ultimately impede their long-term growth. The nonreciprocal preferences could also become an impediment to multilateral trade negotiations because beneficiaries may prefer to seek ways of maintaining them rather than exchanging them for reciprocal benefits.102

For this reason, some economists prefer multilateral, nondiscriminatory tariff cuts because preferential tariff programs, such as the GSP, could lead to inefficient production and trade patterns in developing countries.103 They say that when tariffs are reduced across-the-board, rather than in a preferential manner, countries tend to produce and export on the basis of their comparative advantage—exporting products that they produce relatively efficiently and importing products that others produce relatively efficiently.104

Economic Effects on the U.S. Market

In 2017, products valued at $21 billion (imports for consumption) entered the United States duty-free under the GSP program, out of total imports from eligible BDCs of about $215 billion. In comparison, total U.S. imports from all countries for 2017 amounted to about $2.3 trillion. These figures suggest that the overall effects of GSP on the U.S. economy are relatively small. In addition, most U.S. producers of import-competing products are largely protected from severe economic impact. First, certain products, such as most textile and apparel products, are designated as "import sensitive" and therefore ineligible for duty-free treatment. Second, CNLs are triggered when imports of a product from a single country reach a specified threshold value, or when 50% of total U.S. imports of a product come from a single country.105 Third, U.S. manufacturers or producers may petition the USTR to withdraw GSP benefits from a certain product if they are injured by the preference.106

In federal budgetary terms, according to the Congressional Budget Office cost estimate for the most recent GSP reauthorization legislation (P.L. 115-141), the GSP program was projected to cost the United States (in foregone tariff revenues) about $347 million in 2018, $475 million in 2019, $492 million in 2020, and $129 million in 2021, for a total of about $1.4 billion.107

Many U.S. manufacturers and importers benefit from the lower cost of consumer goods and raw materials imported under the GSP program.108 U.S. demand for certain individual products, including jewelry, leather, and aluminum, is quite significant.109 The Coalition for GSP, a group of U.S. companies and associations that benefit from, and advocate for, the GSP program, asserts that companies in 40 states paid at least $1 million in higher tariffs due to the GSP expiration in 2014, with California firms paying an estimated $100 million in tariffs.110 It asserts that, during periods of GSP expiration, small and medium enterprises (SMEs) bear a disproportionate share of the burden, resulting in lower sales and lost jobs.111 It is also possible, however, that other factors, including slower growth and reduced demand in the U.S. market, contribute to adverse economic impacts on these businesses.

Stakeholders' Concerns

Supporters of the GSP program include beneficiary developing country governments and exporters, U.S. importers, and U.S. manufacturers who use inputs entering under GSP in downstream products. Some Members of Congress favor GSP renewal, because they believe it is an important development and foreign policy tool. Opposing the program are some U.S. producers who manufacture competing products and some in Congress who favor more reciprocal approaches to trade policy. What follows is a thematic approach to the major topics of discussion in the GSP renewal debate.

"Special and Differential Treatment"

Developing countries have long maintained that "special and differential treatment," such as that provided by the GSP, is an important assurance of access to U.S. and other developed country markets in the midst of increasing globalization.112 Many of these countries have built industries or segments of industries based on receiving certain tariff preferences.

Some in Congress and in previous Administrations have expressed the desire to see reciprocal trade relationships with some of the emerging market economies that are still beneficiaries of nonreciprocal U.S. preference programs.113 At the same time, there is continued broad support for preference programs in general, including GSP, CBI, and AGOA.114

Erosion of Preferential Margins

Developing countries have expressed concern about the overall progressive erosion115 of preferential margins as a result of across-the-board tariff negotiations within the context of multilateral trade negotiations such as the Doha Round. In 1997, a study prepared by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) found that the degree of erosion of preferences resulting from Uruguay Round (1986-1994) tariff concessions by the Quad countries (Canada, European Union, Japan, United States) was indeed significant.116 Some economists point out that if multilateral rounds of tariff reductions continue, combined with the proliferation of bilateral and regional trade agreements, the preference may disappear completely unless GSP tariff headings are expanded to include more import-sensitive products.117

One example of present concern of preference erosion could be WTO efforts to provide duty-free, quota-free (DFQF) U.S. market access for all products to all least-developed countries. Many sub-Saharan African countries have expressed concern that an approach like this could place them in direct competition for U.S. market share with other developing countries, thus diluting the value of the preferential treatment that they receive through AGOA.118

Other economists say that preference erosion could be more than outweighed by the benefits of increased market access brought about by multilateral trade liberalization.119 These economists say that, rather than continuing GSP and other preferential programs (either through inertia or concern that removing them would be seen as acting against the world's poorest populations), a better approach might be to "assist them in addressing the constraints that really underlie their sluggish trade and growth performance."120

Underutilization of GSP

Some academic literature on preference programs, including GSP and free trade agreements, suggests that they are not used to their fullest extent. One reason cited is that the benefits accruing to importers may not be worth the additional costs (such as the additional paperwork needed to fulfill the local content rule of origin) associated with claiming the preference.121

Additional literature suggests that some countries may not use GSP for a variety of reasons, including unfamiliarity of exporters with the program; BDC governments not sufficiently promoting the existence of available opportunities under the preference; lack of available infrastructure (for example, undeveloped or damaged roads and ports that impede the efforts to get goods into the international market); developing countries' major products could be deemed import sensitive; or a combination of all of these factors.122 One option for addressing these factors could be to provide assistance to GSP beneficiaries through U.S. trade capacity building efforts similar to those employed as part of AGOA.123 The recent relatively long-term reauthorization of AGOA also encouraged beneficiary countries to develop utilization strategies.124

Trade as Foreign Assistance

No other U.S. trade preference program is more broadly based or encompasses as many countries as GSP. As a result, the program is supported by many observers who believe that it is an effective, low-cost means of providing economic assistance to developing countries. Supporters maintain that encouraging trade by private companies through the GSP program stimulates economic development much more effectively than intergovernmental aid and other means of assistance.125 Economic development assistance through trade is a long-standing element of U.S. foreign policy, and other trade promotion programs such as AGOA and the Caribbean Basin Trade Partnership Act (CBTPA) are also based on this premise.

Conditionality of Preferences

Some supporters of GSP and other nonreciprocal programs assert that the conditions required (such as worker rights and IPR requirements) for GSP qualification provide the United States with leverage that can be used to promote U.S. foreign policy goals and commercial interests.126 For example, after Bangladesh's suspension from GSP benefits in June 2013 due to worker rights and safety issues, officials in Bangladesh reportedly have been working closely with U.S. officials to address the shortcomings.127

In November 2013, the United States and Bangladesh signed a Trade and Investment Cooperation Forum Agreement (TICFA), through which "The United States and Bangladesh will more regularly work together to address issues of concern in our trade and investment relationship."128 In May 2017, during discussions on the TICFA, U.S. officials expressed optimism at Bangladesh's progress, but stopped short of suggesting GSP eligibility for Bangladesh.129 The United States is also working with Bangladesh through engagement in a "Sustainability Compact," a multi-government approach that also involves the governments of the EU and Canada, as well as the International Labor Organization (ILO), "to promote continuous improvements in labor rights and factory safety in the Ready Made Garment and Knitwear Industry in Bangladesh." The last review of the Compact also took place in May 2017. The compact members noted that trade union membership had increased, and Bangladesh's government had made significant progress. At the same time, the compact's members noted recent labor unrest in Ashulia (a suburb of the capital, Dhaka), and called for its resolution.130

Lower Costs of Imports

U.S. businesses that import components, parts, or materials duty-free under the GSP maintain that the preference results in lower costs for these intermediate goods which, in turn, can make U.S. firms more competitive, and the savings can be passed on to consumers. These supporters assert that GSP is as important for many domestic manufacturers and importers as for the countries that receive preferential access for their products.131

Even though most U.S. producers are shielded to a certain extent by CNLs and the exclusion of import sensitive products from GSP eligibility, U.S. manufacturers and workers are still sometimes adversely affected by GSP imports. Some of these companies have petitioned for elimination of specific products from GSP eligibility.132 For example, in 2010, Exxel Outdoors, a U.S. company that manufactures certain non-down sleeping bags, petitioned for their removal from GSP eligibility, claiming that their business operations were being harmed by imports of duty-free sleeping bags from Bangladesh under the GSP program.133 These sleeping bag categories were ultimately removed from GSP duty-free treatment in January 2012.134

Options for Congress

In previous years, Members have suggested various reforms of the GSP program. Possible options include supporting reciprocal tariff and market access benefits through FTAs, renewing the GSP for least-developed beneficiaries only, extending the program in a modified form, or letting the program lapse altogether.

Although the GSP is a nonreciprocal tariff preference, any changes to the program may need to be considered in light of the requirements of the WTO Enabling Clause, as it has been interpreted by the WTO Appellate Body. At a minimum, the United States may need to notify—and possibly consult with—other WTO members regarding any withdrawal or modification of GSP benefits, as required by paragraph 4 of the Enabling Clause.135 The United States could also pursue a WTO waiver were any modifications of the GSP program considered not to comport fully with U.S. WTO obligations

Negotiate Trade Agreements with GSP Countries

Some U.S. policymakers have suggested that some developing countries might benefit more through WTO multilateral negotiations, FTAs, or some form of agreement that could also provide reciprocal trade benefits and improved market access for the United States.136 Arguably, this was one of the policy arguments for the EU's pursuit of Economic Partnership Agreements with many of its former GSP beneficiaries. Since tariff concessions under these agreements would probably apply to more sectors of the economy than GSP, such agreements could increase the likelihood of across-the-board economic stimulation in developing countries. Each one of the United States' current FTA partners, with the exception of Canada and Australia, was at one time a beneficiary of the GSP program.137

Authorize GSP Only for Least-Developed Countries

Some in Congress have expressed the possibility of modifying the GSP so that the benefits apply primarily to least-developed beneficiaries.138 Assuming that many least-developed African beneficiaries139 would continue to receive the GSP preference under AGOA, other LDCs that might benefit from an LDC-only GSP program are Afghanistan, Bhutan, Burma, Burundi, Cambodia, Congo (Kinshasa), Haiti,140 Kiribati, Nepal, Samoa, Somalia, South Sudan, the Solomon Islands, Timor-Leste, Tuvalu, Vanuatu, and Yemen.141 Of these countries, in 2017, the LDCs that made the most use of the program by value were Cambodia ($402 million), Burma ($93.9 million), Congo (Kinshasa, $46.8 million), Nepal ($8.6 million), the Solomon Islands ($2.2 million), Samoa ($1.4 million), Burundi ($1.3 million), and Haiti ($1.2 million).142 U.S. efforts through trade capacity building could help LDCs take greater advantage of the preference.

Reform GSP

Congress could modify the GSP, as it applies to all BDCs. Some of these options could have the effect of expanding the GSP program, while others could serve to restrict its application. Below are some examples of potential modifications.

Expand Application of GSP

Were Congress to expand or enhance application of the GSP, the following options could be considered:

- Expand the list of tariff lines permitted duty-free access. Allow some import-sensitive products to receive preferential access.143

- Increase flexibility of rules of origin requirements. For example, allow more GSP beneficiaries to cumulate inputs with other beneficiaries to meet the 35% domestic content requirement.144

- Eliminate competitive need limitations for BDCs, or raise the thresholds that trigger them.

Restrict Application of Preferences

The following is a list of possible approaches if Congress desired to extend the program but restrict imports under GSP:

- Consider mandatory graduation for "middle income" countries, similar to EU GSP changes, or strengthen the language giving the President authority to graduate countries based on competitiveness.

- Reconsider criteria for graduation of countries from GSP or direct greater enforcement of the eligibility criteria.

- Strengthen provision that allows graduation of individual industry sectors within beneficiary countries.

- Modify the rule-of-origin requirement for qualifying products to require that a greater percentage of the direct costs of processing operations (currently 35%) originate in beneficiary developing countries.145

- Lower the threshold at which the President may (or must) withdraw, suspend, or limit the application of duty-free treatment of certain products (CNLs).146

- Require the President to more frequently and actively monitor (currently an annual process) the economic progress of beneficiary countries, as well as compliance with GSP criteria.

- Add additional eligibility criteria; for example, to include movement toward more reciprocal tariff treatment, sustainable development, or environmental preservation.

Appendix A. GSP Implementation and Renewal

|

Public Law |

Effective Date |

Date Expired |

Notes |

|

P.L. 93-618, Title V, |

January 2, 1975 |

January 2, 1985 |

Statute originally enacted. |

|

P.L. 98-573, Title V, |

October 30, 1984 |

July 4, 1993 |

Substantially amended and restated. |

|

P.L. 103-66, Section 13802 |

August 10, 1993 |

September 30, 1994 |

Extended retroactively from July 5, 1993, to August 10, 1993. Also struck out reference to "Union of Soviet Socialist Republics" |

|

P.L. 103-465, Section 601 Uruguay Round Agreements Act |

December 8, 1994 |

July 31, 1995 |

Extended retroactively from September 30, 1994, to December 8, 1994. No other amendments to provision. |

|

P.L. 104-188, Subtitle J, Section 1952 |

October 1, 1996 (for GSP renewal only) |

May 31, 1997 |

Substantially amended and restated. Extended retroactively from August 1, 1995, to October 1, 1996. |

|

P.L. 105-34, Subtitle H, Section 981 |

August 5, 1997 |

June 30, 1998 |

Extended retroactively from May 31, 1997, to August 5, 1997. No other amendments to provision. |

|

P.L. 105-277, Subtitle B, Section 101 |

October 21, 1998 |

June 30, 1999 |

Extended retroactively from July 1, 1998, to October 21, 1998. No other amendments to provision. |

|

P.L. 106-170, Section 508, |

December 17, 1999 |

September 30, 2001 |

Extended retroactively from July 1, 1999, to December 17, 1999. No other amendments to provision. |

|

P.L. 107-210, Division D, Title XLI |

August 6, 2002 |

December 31, 2006 |

Extended retroactively from September 30, 2001, to August 6, 2002. Amended to (1) include requirement that BDCs take steps to support efforts of United States to combat terrorism and (2) further define the term "internationally recognized worker rights." |

|

P.L. 109-432, Title VIII |

December 31, 2006 |

December 31, 2008 |

Extended before program lapse. |

|

P.L. 110-436, Section 4 |

October 16, 2008 |

December 31, 2009 |

Extended before program lapse. |

|

December 28, 2009 |

December 31, 2010 |

Extended before program lapse. |

|

|

November 5, 2011 |

July 31, 2013 |

Extended retroactively from December 31, 2010, to November 5, 2011. |

|

|

P.L. 114-27, Title II |

July 29, 2015 |

December 31, 2017 |

Extended retroactively from July 31, 2013, to July 29, 2015. |

|

P.L. 115-141, Division M, Title V |

April 22, 2018 |

December 31, 2020 |

Extended retroactively from January 1, 2018 to April 22, 2018. |

Source: CRS analysis using Congress.gov, http://www.congress.gov.

Appendix B. GSP Beneficiary Countries

Table B-1. Beneficiary Developing Countries and Regions for Purposes of the Generalized System of Preferences

(as of May 2018)

|

Independent Countries |

|||||

|

Afghanistan A+ |

Ecuador |

Liberia A+ |

Serbia |

||

|

Albania |

Egypt |

Macedonia |

Sierra Leone A+ |

||

|

Algeria |

Eritrea |

Madagascar A+ |

Solomon Islands A+ |

||

|

Angola A+ Argentina |

Ethiopia A+ |

Malawi A+ |

Somalia A+ |

||

|

Armenia |

Fiji |

Maldives |

South Africa |

||

|

Azerbaijan |

Gabon |

Mali A+ |

South Sudan A+ |

||

|

Belize |

Gambia, The A+ |

Mauritania A+ |

Sri Lanka |

||

|

Benin A+ |

Georgia |

Mauritius |

Suriname |

||

|

Bhutan A+ |

Ghana |

Moldova |

Swaziland |

||

|

Bolivia |

Grenada |

Mongolia |

Tanzania A+ |

||

|

Bosnia and Hercegovina |

GuineaA+ |

Montenegro |

Thailand |

||

|

Botswana |

Guinea-BissauA+ |

Mozambique A+ |

Timor-Leste A+ |

||

|

Brazil |

Guyana |

Namibia |

Togo A+ |

||

|

Burkina Faso A+ |

Haiti A+ |

Nepal A+ |

Tonga |

||

|

Burma A+ |

India |

Niger A+ |

Tunisia |

||

|

Burundi A+ |

Indonesia |

Nigeria |

Turkey |

||

|

Cambodia A+ |

Iraq |

Pakistan |

Tuvalu A+ |

||

|

Cameroon |

Jamaica |

Papua New Guinea |

Uganda A+ |

||

|

Cape Verde |

Jordan |

Paraguay |

Ukraine |

||

|

Central African RepublicA+ |

Kazakhstan |

Philippines |

Uzbekistan |

||

|

Chad A+ |

Kenya |

Republic of Yemen A+ |

Vanuatu A+ |

||

|

Comoros A+ |

KiribatiA+ |

Rwanda A+ |

Zambia A+ |

||

|

Congo (Brazzaville) |

Kosovo |

Saint Lucia |

Zimbabwe |

||

|

Congo (Kinshasa) A+ |

Kyrgyzstan |

Saint Vincent and the Grenadines |

|||

|

Cote d'Ivoire |

Lebanon |

Samoa A+ |

|||

|

Djibouti A+ |

Lesotho A+ |

Sao Tome and Principe A+ |

|||

|

Dominica |

Senegal A+ |

||||

|

Non-Independent Countries and Territories Eligible for GSP Benefits |

|||||

|

Anguilla |

Heard Island and McDonald Islands |

Tokelau |

|||

|

British Indian Ocean Territory |

Montserrat |

Virgin Islands, British |

|||

|

Christmas Island (Australia) |

Niue |

Wallis and Futuna |

|||

|

Cocos (Keeling) Islands |

Norfolk Island |

West Bank and Gaza Strip |

|||

|

Cook Islands |

Pitcairn Islands |

Western Sahara |

|||

|

Falkland Islands (Islas Malvinas) |

Saint Helena |

||||

|

Associations of Countries (treated as one country) |

|||||

|

Member Countries of the Cartagena Agreement (Andean Group) |

Member Countries of the West African Economic and Monetary Union (WAEMU) |

Qualifying Member Countries of the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN) Cambodia |

|||

|

Qualifying Member Countries of the Southern Africa Development Community (SADC) |

Qualifying Member Countries of the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) |

Qualifying Member Countries of the Caribbean Common Market (CARICOM) |

|||

Source: Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the United States, 2017, Revision 1, July 2017.

Note: "A+" indicates least-developed countries.