Several high-profile incidents where police officers have been involved in the deaths of citizens1 reinvigorated a discussion about how the police use force against minorities and the tension that exists between police officers2 and minority communities. The national debate about how police use force and police-community relations might generate interest among policymakers about what role Congress could play in facilitating efforts to build trust between the police and the people they serve, as well as police accountability for any excessive use of force.

The report starts with an overview of data on public opinion of the police. It then provides a brief discussion of federalism and why Congress does not have the authority to directly change state and local law enforcement practices. Next, the report reviews federal efforts to collect data on law enforcement agencies' use of force and federal authority to investigate instances of police misconduct. This is followed by a review of what role DOJ might be able to play in facilitating improvements in police-community relations or making changes in state and local law enforcement agencies' policies. The report concludes with policy options for Congress to consider should policymakers decide to exert some influence on state and local law enforcement agencies' policy.

|

The Parameters of This Report This report provides a brief overview of police-community relations and how policymakers might be able to promote improved relationships between the police and their constituents, especially people of color. The report focuses solely on the relationship between the police and the communities they serve. It does not include a discussion of the level of trust in or perceived discrimination by other parts of the criminal justice system (i.e., the grand jury system, prosecutions, or corrections). The report also focuses on issues related to state and local law enforcement agencies and not federal law enforcement agencies. It focuses on state and local law enforcement agencies because congressional interest in this topic has largely centered on what role Congress might play in promoting a better relationships between state and local law enforcement agencies and their communities and how Congress could promote more accountability for state and local law enforcement officers' use of excessive force. |

Public Perception of the Police

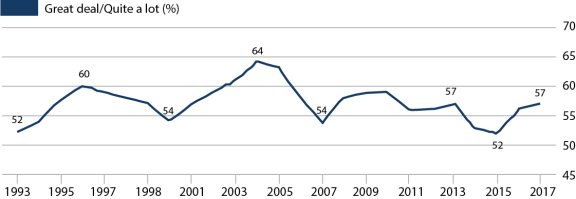

Gallup, whose polling tracks confidence in a variety of institutions, found that the public's level of confidence in police is back to its historical norm after a decrease in 2014 and 2015 (see Figure 1).3 In 2017, 57% of Americans said they had a "great deal" or "quite a lot" of confidence in the police, which matched the 25-year average for Gallup polling. Fifty-seven percent of Americans reported that they had a "great deal" or "quite a lot" of confidence in the police in 2013, but confidence decreased to 53% in 2014, and decreased again to 52% in 2015, which was a historical low in Gallup polling. Even at its nadir in 2015, people still had more confidence in the police than many other institutions.4 Only the military (72%) and small business (70%) had higher percentages of respondents voicing confidence in the respective institutions than the police.5

Confidence in the police varies by race/ethnicity, political ideology, and age (see Table 1). Whites were more likely to say that they have a "great deal" or "quite a lot" of confidence in the police than Hispanics and blacks. In addition, whites' confidence in the police has increased while that of Hispanics and blacks has decreased. Variability in confidence is also evidenced among people who identify as conservative, moderate, and liberal. Conservatives are more likely than liberals and moderates to have confidence in the police, and their confidence has increased in recent years while that of moderates and liberals has decreased. In addition, a smaller proportion of people age 18-34 said they were confident in the police compared to people age 35-54 and people 55 and older, with the 55 and older group having the greatest proportion of people saying that they had a "great deal" or "quite a lot" of confidence in the police.

Table 1. Confidence in the Police, by Demographic Group

Percentage who have a "great deal" or "quite a lot" of confidence in the police

|

Demographic Group |

2012-2014 |

2015-2017 |

|

Race/Ethnicity |

||

|

Hispanic |

59% |

45% |

|

Black |

35% |

30% |

|

White |

58% |

61% |

|

Political Ideology |

||

|

Liberal |

51% |

39% |

|

Moderate |

56% |

53% |

|

Conservative |

59% |

67% |

|

Age |

||

|

18-34 |

56% |

44% |

|

35-54 |

53% |

54% |

|

55 or older |

58% |

63% |

Source: CRS presentation of data from Jim Norman, "Confidence in Police Back at Historical Average," Gallup, July 10, 2017.

Federalism and Congressional Control over State and Local Law Enforcement Policy

Policymakers may have an interest in trying to help increase trust between the police and certain communities, particularly in urban areas. Policymakers may seek to increase law enforcement agencies' accountability for any excessive use of force and address state and local law enforcement policies they believe contribute to the lack of public trust in police. However, the United States' federalized system of government places limits on the influence Congress can have over state and local law enforcement policies.

Overview of Federalism

Federalism describes the intergovernmental relationships between and among federal, state, and local governments, with the federal government having primary authority in some areas and state and local governments having primary authority in other areas.6 Scholars have variously described these relationships as being primarily "dual," "cooperative," "creative," "coercive," or, more recently, "fragmented" federalism. Early characterizations of the American system described a dual federalism in which the federal and state governments were equal partners with relatively separate and distinct areas of authority. Scholars argue that American federalism is presently "more chaotic, complex, and contentious than ever before."7 This has led to a fragmented federalism in which states and the federal government simultaneously pursue their own policy priorities, and policy implementation often occurs in a piecemeal, disjointed fashion.8

Federalism and State and Local Law Enforcement Agencies

Under the authority of the Spending Clause of the U.S. Constitution, Congress may choose to impose conditions on federal grant awards to state and local governments as a way to influence state and local policy.9 As one scholar noted, congressional conditioning of federal grants related to state and local policing under the authority of the Spending Clause has been questioned:

Law enforcement historically has been considered one of these attributes of state sovereignty upon which the federal government cannot easily infringe. Thus, Congress is greatly restricted in the degree to which it can regulate a state's administration of its local law enforcement agencies. Because of this limited power over the states, particularly in areas such as law enforcement, Congress cannot "commandee[r] the legislative processes of the States by directly compelling them to enact and enforce a federal regulatory program. Furthermore, even if Congress has the authority to regulate or prohibit certain acts if it chooses to do so, it cannot force the states "to require or prohibit those acts."10

In contrast, another scholar has suggested that federal grants to law enforcement agencies are a way to encourage police accountability and argued that "federal funds issued to states ... should be conditioned upon the enactment and implementation of police accountability measures aimed at institutional reform."11

That same scholar also suggested that the use of federal grants to state and local law enforcement agencies can encourage a cooperative federalism relationship that entails federal-state collaboration and allows states some flexibility in implementing federal standards while preserving state and local abilities to enhance police accountability.12 Another federalism scholar noted that cooperative federalism was "a pragmatic middle ground between reform and reaction that would not destroy the states but would still lower their salience from constitutionally coordinate polities to more congenial laboratories of democracy and administrators of national policy."13

While there is limited research on the evolving nature of federalism within law enforcement policy, the congressional use of federal grants to state and local law enforcement agencies, and the cooperative federalism that generally exists through their use, suggest that the federalism relationship in this area may be less fragmented than in other policy areas. It is unclear how changes in federal interaction with state and local law enforcement agencies might affect the nature of federalism outside this specific policy area.

Even though there are limits on how much influence Congress and the federal government can have on state and local law enforcement policy, the federal government does currently have some tools that might be used to promote better police-community relations and accountability. These include (1) federal efforts to collect and disseminate data on the use of force by law enforcement officers; (2) statutes that allow the federal government to investigate instances of police misconduct; and (3) the influence DOJ has on state and local law enforcement policies through its role as a public interest law enforcer, policy leader, convener, and funder of law enforcement agencies.

Federal Efforts to Collect Data on Law Enforcement Officers' Use of Force

The high-profile deaths of several members of the public at the hands of police officers has generated questions about why the federal government does not collect and publish data on the use of force by law enforcement officers. Former Philadelphia Police Chief Ramsey, one of the co-chairs of the Task Force on 21st Century Policing, stated "personally, I think [how data on civilian and law enforcement officers' deaths are collected] ought to be pretty much the same. If you don't have the data, people think you are hiding something.... This is something that comes under the header of establishing trust."14 It may be that the lack of reliable data on how often police use force and who is the subject of the use of force fuels the public's mistrust of the police. Without more comprehensive data to provide context in this area, the public is left to rely on media accounts of excessive force cases for information. The lack of comprehensive federal data on police-involved deaths led the Washington Post to start its own database of people who have been shot and killed by the police.15

The federal government currently has several different programs that collect some data on police-involved shootings and the use of force. However, none of these programs collects data on every use of force incident in the United States.

Uniform Crime Reports

Currently, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), through the Uniform Crime Report (UCR), collects data on justifiable homicides by law enforcement officers.16 It does not collect data on shootings that do not result in a death, nor does it capture data in instances where an officer shoots at a suspect but does not hit him or her. Also, law enforcement agencies participate in the UCR program voluntarily, which means that justifiable homicides by law enforcement agencies may be undercounted.17 One DOJ statistician has stated that "the FBI's justifiable homicides [data] ... [has] significant limitations in terms of coverage and reliability that [are] primarily due to agency participation and measurement issues."18

The Federal Bureau of Investigation's Use of Force Data Collection

The FBI notes that "the opportunity to analyze information related to use-of-force incidents and to have an informed dialogue is hindered by the lack of nationwide statistics."19 The FBI reports that it is working with major law enforcement organizations to collect national use of force data. The stated goal of the program is "is not to offer insight into single [use of force] incidents but to provide an aggregate view of the incidents reported and the circumstances, subjects, and officers involved."20 Also, the data will not assess whether the officers involved in use of force incidents acted lawfully or within the bounds of department policy.

The FBI plans to collect data on use of force incidents that results in the death or serious bodily injury21 of a person or when a law enforcement officer discharges a firearm at or in the direction of a person. For each incident, the FBI plans to collect data on the circumstances surrounding the incident (e.g., date and time, the number of officers who applied force, the reason for the initial contact between the officer and the subject), subject information, and officer information.22 Local law enforcement agencies would be responsible for submitting use of force data to the FBI and participation will be voluntary. The FBI reports that it plans to periodically release use of force statistics to the public and it will publish descriptive information on trends and characteristics of the data.

The FBI reported that it launched a six-month pilot study of its national use of force data collection program on July 1, 2017, which concluded at the end of the year. It provided a report on its findings from the pilot study to the Office of Management and Budget for review and approval. The FBI reported that upon approval it anticipates starting a nationwide data collection effort; however, the results of the pilot study have not been released and there have been no reports as to whether it has started collecting these data.

Contacts between the Police and the Public

Section 210402 of the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994 (P.L. 103-322) requires the Attorney General to "acquire data about the use of excessive force by law enforcement officers" and to publish an annual summary of the data. DOJ has struggled to fulfill this mandate.23 In April 1996, the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) and the National Institute of Justice (NIJ) published a status report on their efforts to fulfill the requirements of the act.24 This report summarized the results of studies that examined the issue of police use of force. The report also highlighted difficulties in collecting use of force data, including defining terms such as use of force, use of excessive force, and excessive use of force; reluctance by police agencies to provide reliable data; concerns about the misapplication of reported data; the lack of attention to provocation in the incident leading to the use of force; and the degree of detail needed to adequately describe individual incidents.

In November 1997, BJS released a second report about its efforts: Police Use of Force: Collection of National Data. This report described a pilot project, a survey of approximately 6,400 people who in the past year had initiated an interaction with a law enforcement officer. The survey asked respondents about the types of interactions they had with law enforcement officers, both positive and negative. The pilot project eventually led to BJS's Police Public Contact Survey (PPCS). The report also noted that both BJS and NIJ had funded a National Police Use-of-Force Database Project. The project was administered by the International Association of Chiefs of Police (IACP), and it was developed as a pilot effort to collect incident-based use-of-force information from local law enforcement agencies. The IACP published a report in 2001 using the data it collected through its National Police Use-of-Force Database Project.25 Critics of the study argue that because the data were submitted voluntarily, the results are incomplete and inconclusive.26

Even though DOJ does not publish annual data on the use of excessive force by law enforcement officers, it has attempted to implement the requirements of Section 210402 by collecting data on citizens' interactions with police―including whether the police threatened to use or have used force, and whether the respondent thought the force was excessive―every three years starting in 1996 through its PPCS.27 One limitation of the PPCS is that it is a survey administered to a sample of law enforcement agencies, so while it might be able to generate a reliable estimate of when citizens report law enforcement officers using force against them, it is not a census of all such incidents.

Death in Custody Reporting Program

DOJ also collected data on arrest-related deaths pursuant to the Death in Custody Reporting Act of 2000 (DCRA, P.L. 106-297). The act required recipients of Violent Offender Incarceration/Truth-in-Sentencing Incentive grants28 to submit data to DOJ on the death of any person who is in the process of arrest, en route to be incarcerated, or incarcerated at a municipal or county jail, state prison, or other local or state correctional facility (including juvenile facilities). The provisions of the act expired in 2006.29 Congress reauthorized the act by passing the Death in Custody Reporting Act of 2013 (P.L. 113-242). The act requires states to submit data to DOJ regarding the death of any person who is detained, under arrest, in the process of being arrested, en route to be incarcerated, or incarcerated at a municipal or county jail, a state prison, a state-run boot camp prison, a boot camp prison that is contracted out by the state, any state or local contract facility, or any other local or state correctional facility (including juvenile facilities). States face up to a 10% reduction in their funding under the Edward Byrne Memorial Justice Assistance Grant (JAG) program if they do not provide the data.30 The act also extends the reporting requirement to federal agencies.

BJS established the Death in Custody Reporting Program (DCRP) as a way to collect the data required by the Death in Custody Reporting Act of 2000, and it continued to collect data even though the initial authorization expired in 2006. DCRP collected data on both deaths that occurred in correctional institutions and arrest-related deaths, though BJS suspended collection of arrest-related deaths in 2014. BJS acknowledged problems with arrest-related deaths data before suspending the data collection effort. In a report on arrest-related deaths for 2003-2009, BJS notes that "arrest-related deaths are under-reported" and that the data are "more representative of the nature of arrest-related deaths than the volume at which they occur."31

BJS has replaced the DCRP with the Mortality in Correctional Institutions (MCI) program, which collects data on deaths that occur while inmates are in the custody of local jails, state prisons (including inmate housed in private prisons), or the Bureau of Prisons. BJS notes that MCI collects "many, but not all, of the elements outlined in the DCRA reauthorization (P.L. 113-242), but because MCI is collected for statistical purposes only, it cannot be used for DCRA enforcement." It is not clear how BJS will operationalize the other requirements of DCRA.

Data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) receives and publishes death certificate data voluntarily provided to it by all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and the territories.32 For publication of national data on violent deaths, CDC codes the intent or manner of death, such as suicide, homicide, legal intervention, or unintentional (among others). Legal intervention is defined as "injuries inflicted by the police or other law-enforcing agents, including military on duty [excluding operations of war], in the course of arresting or attempting to arrest lawbreakers, suppressing disturbances, maintaining order, and other legal action."33

There are few published studies of deaths attributed to legal intervention in the United States. A recent analysis compared vital statistics data (i.e., death certificates) and a news-media-based dataset, finding that, for 2015, the media-based data reported more than twice as many law-enforcement-related deaths as the vital statistics data.34

In 2002, CDC launched the National Violent Death Reporting System (NVDRS), a state-based surveillance system for violent deaths. As of FY2018, NVDRS is funded to operate in all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico.35 Personnel in these jurisdictions gather and link records from law enforcement sources, coroners and medical examiners, vital statistics, and crime laboratories to report violent deaths in NVDRS, providing better quality information about the causes of and means to prevent violent deaths than is available from death certificates alone.36

Authority for DOJ to Investigate Law Enforcement Misconduct

The federal government has several legal tools at its disposal to ensure that state and local law enforcement practices and procedures adhere to constitutional norms.37 The first is criminal enforcement brought directly against an offending officer under several federal civil rights statutes. Section 242 of Title 18 makes it a federal crime to willfully deprive a person of their constitutional rights while acting under color of law.38 Similarly, Section 241 of Title 18 outlaws conspiracies to deprive someone of their constitutional rights.39 These statutes, enacted during the Reconstruction Era following the Civil War, were primarily intended to safeguard rights newly bestowed on African Americans under the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments.40 In more recent years, these statutes have formed the basis of police excessive force criminal cases,41 and form the legal justification for DOJ investigations into several recent police killings across the country.42

Arguably, the most contentious issue surrounding Section 242 has been its mens rea, or mental state, element. In the 1945 case Screws v. United States, the Supreme Court interpreted the predecessor of Section 242 to require that the officer have the specific intent of depriving the person of their civil rights.43 The lower courts have parsed Screws to require varying mens rea thresholds, with some instructing that the officer must act with "a bad purpose or evil motive,"44 while others require a less stringent "reckless disregard" standard.45 Some view the intent threshold as blocking too many meritorious cases and argue that it should be lowered to adequately protect civil rights.46

The second major legal tool is a federal statute that focuses on civil liability of law enforcement agencies as a whole, rather than on the wrongdoing of individual officers. Enacted as part of the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994, and codified at 34 U.S.C. Section 12601, this statute prohibits government authorities or agents acting on their behalf from engaging in a "pattern or practice of conduct by law enforcement officers ... that deprives persons of rights ... secured or protected by the Constitution or laws of the United States."47 It authorizes the Attorney General to sue for equitable or declaratory relief when he or she has "reasonable cause to believe" that such a pattern of constitutional violation has occurred.

The scope of investigations under Section 12601, primarily conducted by the Special Litigation Section of DOJ's Civil Rights Division, has ranged from police use of force and unlawful stops and searches to racial and ethnic biases.48 Traditionally, these investigations are resolved by consent decree—a judicially enforceable settlement between DOJ and the local police department that outlines the various measures the local agency must take to remedy its unconstitutional police practices. For instance, after two years of extensive investigation into the New Orleans Police Department's policies and practices in which DOJ found numerous instances of unconstitutional conduct, DOJ entered into a consent decree with the City of New Orleans requiring the city to implement new policies and training to remedy these constitutional violations.49 The content of each consent decree can differ, but many include provisions concerning use-of-force reporting systems, citizen complaint systems, and early warning systems to identify problem officers.50 However, using consent decrees as a mechanism to reform policing practices is subject to the priorities of a given administration. For example, during the Obama Administration, DOJ used its authority under Section 12601 to open pattern and practice investigations of several police departments.51 However, former Attorney General Sessions announced that DOJ would be limiting the use of consent decrees to force changes in local police departments.52

What Role Might the Department of Justice Play in Improving Police-Community Relations?

DOJ and its component agencies such as the FBI can help shape policing in the United States. Such influence can be seen in at least four roles that DOJ and its components fill on this stage

- Law enforcer—investigating and prosecuting violations of federal law related to police abuse of power.

- Policy leader—setting standards on law enforcement issues.

- Convener—bringing together key parties on sensitive, relevant, and important issues.

- Funder—awarding grants to state and local police as well as researchers probing important policing questions.53

DOJ as Law Enforcer

As noted elsewhere in this report, DOJ has a hand in shaping the way state and local police operate by enforcing federal laws covering the conduct of such agencies.54 Success in these efforts could enhance public confidence in the oversight of the police. To this end, DOJ's Civil Rights Division and the FBI rely on their authority to pursue officials or agencies depriving persons of their constitutionally protected rights. Such actions can be broken down into "color of law"55 cases and "pattern or practice"56 investigations (discussed above).

The FBI is the lead federal agency for investigating color of law abuses and can initiate cases involving official misconduct, which DOJ can prosecute.57 Such cases involve excessive force, sexual assault, false arrests and fabrication of evidence, or failure to keep from harm.58

Additionally, DOJ's Civil Rights Division can review the patterns or practices "of law enforcement agencies that may be violating people's federal rights"59 and seek civil remedies when "law enforcement agencies have policies or practices that foster a pattern of misconduct by employees." Such remedies target agencies, not individual officers. DOJ reviews can be initiated when agencies are suspected of

- lack of supervision/monitoring of officers' actions;

- lack of justification or reporting by officers on incidents involving the use of force;

- lack of, or improper training of, officers; and

- citizen complaint processes that treat complainants as adversaries.60

Despite DOJ's authority to prosecute police misconduct, experts have highlighted a number of challenges. Some have suggested, for instance, that the burden of proof is on DOJ to "prove a defendant's specific intent to deprive a victim of constitutional rights,"61 and this may make it difficult to convict someone of misconduct. In addition, even with a successful prosecution some are skeptical as to whether such an outcome incentivizes sweeping institutional changes to prevent future misconduct.62 Regardless, "the Civil Rights Division is not the most direct mechanism of police oversight in the nation, nor is it the primary mechanism on which the people of any single jurisdiction rely; but ... it has been the most steady and longest lasting instrument of police accountability in the United States."63

DOJ as Policy Leader

DOJ can serve as a model for state and local law enforcement agencies. For example, it issues guidance for U.S. police work; sets policies for its own agencies that resonate broadly in federal, state, and local law enforcement agencies; sponsors studies that examine policing practices; and provides training.

- Issuing guidance. One relevant illustration of DOJ's dissemination of guidance is a December 2014 product offering direction on the use of race, ethnicity, gender, national origin, religion, sexual orientation, or gender identity in police work. This guidance is directed at federal policing agencies as well as state and local police active on federal task forces.64 In issuing this guidance, DOJ noted its belief that "law enforcement practices free from inappropriate considerations ... strengthen trust in law enforcement agencies and foster collaborative efforts between law enforcement and communities to fight crime and keep the Nation safe."65 The 2014 document expanded on guidance issued by DOJ in 2003.

- Setting polices for DOJ agencies. DOJ also sets policies for its own agencies that may also be used by state and local law enforcement agencies. For example, domestic investigations at the FBI are governed by principles articulated by DOJ.66 These purportedly "make the FBI's operations in the United States more effective by providing simpler, clearer, and more uniform standards and procedures." Such principles set the investigative standards for task forces that the FBI leads. These task forces often include state and local officers and follow DOJ standards in their task force casework.

- Sponsoring studies on policing practices. DOJ agencies, such as the National Institute of Justice (NIJ) and the Community Oriented Policing Services (COPS) Office, sponsor studies that are intended to help state and local law enforcement agencies address policing challenges. One such product sponsored by the COPS Office, a report focused on the use of body-worn cameras by police, was published in 2014.67 In 2017, DOJ released a report on how police departments can change policies and improve training to help build their relationships with members of the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer or questioning community.68

- Providing training. In 2014, responding to circumstances in Ferguson, MO, DOJ developed a national initiative to enhance trust between the police and public. According to DOJ, among other things the initiative will involve a "substantial investment in training."69 In March 2015, then-Attorney General Eric Holder announced a $4.75 million initiative in six cities70 for the National Initiative for Building Community Trust and Justice.71 More routine examples of training are sponsored by NIJ, which offers training to state and local law enforcement agencies on a wide variety of topics.72 Also, in 2017, DOJ awarded a grant to the International Association of Chiefs of Police (IACP) to fund the Collaborative Reform Initiative Technical Assistance Center. The IACP will partner with other national law enforcement organizations, such as the Fraternal Order of Police and the Major Cities Chiefs Association, to provide training and technical assistance to local law enforcement agencies.

Notably, DOJ sets polices for its own agencies that can be binding, but guidance issued by the DOJ to police forces around the country are typically just that—guidance. As such, some may be skeptical as to the true impact of DOJ as a policy setter for nationwide policing.

DOJ as Convener

DOJ's Community Relations Service (Service) brings together representatives from law enforcement agencies and local communities to discuss policing issues. For example, the Service was sent to Ferguson, MO, after the shooting of Michael Brown.73 The Service describes itself as a "'peacemaker' for community conflicts and tensions arising from differences of race, color, national origin, gender, gender identity, sexual orientation, religion and disability."74 Geared toward conflict resolution strategies, it does not investigate or prosecute crimes, but rather participates in discussions among community stakeholders such as police, government officials, residents, and a wide variety of community-based organizations (e.g., faith-based groups, businesses, and advocacy organizations). Additionally, the Service notes that it does not take sides in a dispute, impose solutions, assign blame, or assess fault.75 Rather, it offers services geared toward the following:

- Mediation. Relying on structured in-person negotiations led by conflict resolution specialists, this process "is not used to determine who is right or who is wrong."76 The goal of mediation is to "provide community members with a framework to help them resolve understandings, establish trust and build the local capacity to prevent and respond to future conflicts."

- Facilitation. Conflict resolution specialists facilitate discussion among stakeholders within particular communities. Such discussions can cover topics such as "race, police-community relations, perceived hate crimes, tribal conflicts, protests and demonstrations, and other issues of importance to community members."77

- Training. The Service provides nine programs that improve cultural competency, provide best practices on things such as collaboration with minority communities and protecting places of worship, and develop conflict resolution skills.78

- Consulting. The Service also work with communities to help them respond more effectively in resolving conflicts and to improving stakeholders' ability to communicate about tension and conflict.

At the national level, DOJ can also convene law enforcement, policy, and academic experts to discuss issues of local importance. For example, the COPS Office and the Police Executive Research Forum (PERF), brought together "police executives, DOJ officials, academics and other experts to discuss constitutional policing as a cornerstone of community policing" in December 2014.79 COPS and PERF published the proceedings of the one day session as a resource for law enforcement agencies.80 In 2015, DOJ convened a task force on 21st Century Policing, which was tasked with identifying best practices and offering recommendations on how law enforcement agencies can both promote crime reduction and build public trust.81 In 2017, DOJ released two reports that summarized the discussions held at two forums convened by DOJ that focused on police recruiting and hiring in the 21st century.82

DOJ as Funder

DOJ operates grant programs to assist state and local law enforcement agencies in their efforts to address crime in their jurisdictions. Two of the most prominent examples are

- COPS grants. The mission of the COPS program is to advance community policing in all jurisdictions across the United States. The COPS Office "advances the practice of community policing by the nation's state, local, territorial, and tribal law enforcement agencies through information and grant resources."83

- The Edward Byrne Memorial Justice Assistance Grant (JAG) program. JAG provides funding to state, local, and tribal governments for state and local initiatives, technical assistance, training, personnel, equipment, supplies, contractual support, and criminal justice information systems in one or more of seven program purpose areas. The program purpose areas are (1) law enforcement programs; (2) prosecution and court programs; (3) prevention and education programs; (4) corrections and community corrections programs; (5) drug treatment and enforcement programs; (6) planning, evaluation, and technology improvement programs; (7) crime victim and witness programs (other than compensation); and (8) mental health and related law enforcement and corrections programs, including behavioral programs and crisis intervention teams.84

Policy Options for Congress

Policymakers might consider the pros and cons of several options if they want to help promote better police-community relations or increase law enforcement agencies' accountability while promoting effective crime reduction. These options include (1) placing conditions on federal funding to encourage state and local governments to adopt policy changes; (2) expanding efforts to collect data on the use of force by law enforcement officers; (3) promoting the use of body-worn cameras; (4) taking steps to facilitate more investigations and prosecutions of deaths that result from excessive force; (5) promoting community policing activities through COPS grants; and (6) using the influence of congressional authority to affect the direction of national criminal justice policy.

Conditions on Federal Funding

As previously discussed, Congress does not have direct control over state and local law enforcement policies. However, Congress can attempt to influence these polices by placing conditions on grant programs that provide assistance to state and local law enforcement agencies. The JAG program is frequently considered for such conditions because it is a formula grant program that provides funding to state and local governments for law enforcement purposes.85 Congress might consider reducing a state and local law enforcement agency's JAG allocation or making receipt of JAG funding contingent upon adopting a certain policy change. While the majority of JAG funding for FY2016 (the most recent year for which detailed data are available) was used for law enforcement programs, state and local governments also used their funding for other programs, such as "prosecution, courts, and public defense"; "planning and evaluation"; "prevention and education"; "corrections and community corrections"; "crime victims and witness services"; and "drug treatment and courts."86

The broad nature of the activities funded under the JAG program means that if Congress were to reduce a state or local government's allocation for not adopting a certain policy change, the potential reduction in funding could result in the state or locality having to cut funding for non-law enforcement purposes and shifting that funding to law enforcement in order to compensate for reduced federal funding. On the one hand, it could be argued that this would provide a strong inducement for states and local governments to adopt the policy change (e.g., state and local governments would comply with the requirement because they would not want to lose funding for law enforcement and other important programs). On the other hand, it could penalize agencies (e.g., corrections, prosecutors, courts, and public defenders offices) that have no control over whether law enforcement agencies adopt the policy change. Also, some allocations (e.g., for law enforcement agencies serving small jurisdictions) might not be large enough to convince law enforcement agencies to comply with the requirement, especially if the cost of complying exceed the agency's allocation.

Policymakers might also consider making state and local law enforcement agencies ineligible to apply for funding under competitive grant programs that provide funding for law enforcement personnel, equipment, or programs unless they adopt a certain policy. This option might be effective for bringing about changes in state and local law enforcement policy because law enforcement agencies would lose access to federal funding unless they comply with the condition(s). Also, unlike a formula grant program where each law enforcement agency can only apply for its allocated amount, law enforcement agencies can apply for an amount of funding from a competitive grant program that is equal to its needs. For example, a small law enforcement agency might only be eligible to receive $15,000 under the JAG program, but under the Community Oriented Policing Services (COPS) hiring program, it could apply for up to $125,000 to hire a new officer. However, making some law enforcement agencies ineligible to apply for funding under a specific grant program would not provide an incentive to change for those agencies that do not seek to apply for a grant under the program.

Expanding Efforts to Collect Data on Police Use of Force

As previously discussed, there is a lack of comprehensive and reliable data on law enforcement officers' use of force, though the FBI is trying to address the issue with its use of force data collection efforts. Policymakers may have an interest in collecting more comprehensive data to help them understand when and against whom law enforcement officers are using force, which could help formulate use of force policy. Collecting more detailed data on how the police use force could provide insight into whether the use of excessive force are the result of a few "bad apples" or is more of a systemic issue. More complete data could also help law enforcement agencies develop best practices about when to use force and how much force is necessary in specific circumstances.

There are several issues policymakers could consider if Congress wants the federal government to expand use of force data collection efforts. The first question might be how much data should the federal government collect? Should it only collect data in cases where a law enforcement officer kills someone, or should it collect data on all use of force incidents? In the latter option, how would use of force be defined? BJS noted the difficulty with defining use of force, excessive force, and excessive use of force the last time Congress required DOJ to collect these data. Limiting data collection efforts to instances where a law enforcement officer engages in an action that results in someone's death would be easier to define, thereby making it easier to collect reliable data, but it omits data on many other use of force incidents. As one academic, and former police officer, who studies police use of force has noted, "[e]very study that I'm aware of shows that most of the people who are shot by the cops survive and most of the time when cops shoot the bullets don't hit. If your statistics look just at dead bodies you'd be under-counting it by 85 percent. If the cops are shooting, we need to [know] when they are shooting, not just when they kill somebody with the bullets."87

Another issue is how the federal government would collect police-involved shootings or use of force data. Congress could consider requiring the FBI to collect the data on use of force incidents through the UCR. As mentioned above, the FBI has taken steps to expand its efforts to collect more data on the use of force by police, but this is an administrative effort, and not the result of congressional action. However, participation in the UCR is voluntary, and the reliability and validity of the data is dependent on full participation of law enforcement agencies. When the FBI announced its effort to collect of use of force data, the FBI noted that participation will continue to be voluntary.88 FBI officials reported they lack the legal authority to mandate data submission.89

Congress could consider making data submission on use of force incidents a condition of receiving federal funding. In 2014, Congress reauthorized the Death in Custody Reporting program (P.L. 113-242). States are required to submit data on certain deaths (e.g., deaths that occur in jails, state prisons, or the Bureau of Prisons), or face losing up to 10% of their JAG funding. Because states are only required to submit data on deaths in custody, data on all use of force incidents are not captured.

If Congress were to make submitting use of force data a requirement to receive federal funding, there still might be questions about the reliability of the data. If Congress put in place a requirement for agencies to submit reliable data, how would it be verified? Would the FBI have the resources to verify that all law enforcement agencies accurately reported all of the incidents where their police officers used force? Also, depending on the size of the potential penalty, some law enforcement agencies might forgo federal funding rather than report the data.

Congress might consider getting states more involved in the process of collecting data on the use of force. Policymakers could consider making a state and all jurisdictions in it ineligible for federal law enforcement funding if the state does not have a law requiring all law enforcement agencies in the state to report use of force data and submits the data to DOJ. States would have to oversee fewer law enforcement agencies than DOJ would if it were solely responsible for collecting the data. This is similar to the strategy of the UCR program where most states serve as collectors and coordinators of local law enforcement offense and arrest data and then submit those data to the FBI. State government agencies might also have more knowledge of police-involved shootings in the state, so it is possible that police-involved shooting data would be more complete if they were collected by the state. However, it seems improbable that state agencies would be aware of all of the instances where law enforcement officers used force, so this option might still result in incomplete use of force data. Also, this option might be considered too coercive because some jurisdictions might not be eligible to receive federal funding if the state did not act.

A potentially less coercive option would be to require BJS to conduct an annual survey of law enforcement agencies to collect data on their use of force. However, since law enforcement agencies would not be required to respond to the survey, it is possible that the results would under-estimate the number of officer-involved shootings or use of force incidents.

Promoting the Use of Body-Worn Cameras

Body-worn cameras (BWCs) are mobile cameras that allow law enforcement officers to record what they see and hear. They can be attached to a helmet, a pair of glasses, or an officer's shirt or badge. From FY2016 to FY2018, Congress appropriated $67.5 million for a grant program under DOJ to help law enforcement agencies purchase BWCs.

There are several perceived benefits to the use of BWCs by law enforcement officers. One of the primary perceived benefits is that they are expected to have a civilizing and deterrent effect on both officers and citizens, resulting in fewer citizen complaints, less use of force by officers, and fewer assaults on officers. One review of the research on BWCs suggests that they result in fewer citizen complaints and less use of force by officers.90 However, the Center for Evidence-Based Crime Policy at George Mason University conducted their own review of the literature on BWCs and concluded "[we] refrain at this point from drawing any definitive conclusions about BWCs from the twelve existing studies because there are so few of them."91 The researchers at George Mason University believe that the existing literature on BWCs generates more questions than answers.

Two more recent studies involving the Metropolitan Police Department (MPD, Washington, DC) and the Las Vegas Metropolitan Police Department (LVMPD) provide mixed evidence on BWCs effect on police use of force and citizen complaints. In both studies, police officers were randomly assigned to a treatment group (i.e., officers who wore BWCs) and control group (i.e., officers that did not wear BWCs). The use of random assignment helps increase the internal validity of the results (i.e., that the measured outcomes were the result of the use of BWCs rather than the result of differences between the treatment and control groups). The LVMPD study found officers in the treatment group were 14% less likely to have a citizen complaint filed against them and 12.5% less likely to report that they used force.92 However, the MPD study found no statistically significant difference in citizen complaints or documented use of force incidents between officers who were assigned to wear BWCs and those who did not.93

Congress could consider authorizing a new grant program that would provide funding for law enforcement agencies to purchase BWCs.94 One potential model for such a program would be the Matching Grant Program for Armor Vests. The program provides grants to state, local, and tribal governments to help purchase armor vests for use by law enforcement officers and court officers. Grants under the program cannot pay for more than 50% of the cost of purchasing a new armor vest. Before authorizing a BWCs funding program, policymakers may consider the following issues:

- How much would it cost to supply BWCs to all law enforcement agencies to ensure that all their sworn officers have BWCs? BJS reports that 47% of all police departments and sheriff's offices have acquired BWCs and 45% of police departments and sheriff's offices have at least some BWCs in service.95 BJS also reports that for police departments and sheriff's offices where they have already deployed BWCs there are 29 BWCs per 100 full-time sworn officers and for agencies where BWCs are to be deployed in the next year there are 21 BWCs per 100 full-time sworn officers.96 The data indicate that only half of all law enforcement officers have or will have a BWC. A market survey conducted by the National Institute of Justice shows that BWCs can cost anywhere from $120 to $1,000.97 The median price of a BWC included in the survey was $499.

- Should all law enforcement officers be required to wear BWCs? For example, should officers in law enforcement agencies that serve small jurisdictions or those with relatively low crime rates be required to wear them? Would it be more effective to allocate funding to outfit officers in larger jurisdictions or those with higher crime rates with BWCs?

- There are costs to law enforcement agencies beyond the cost of purchasing BWCs. For example, there would be maintenance and replacement costs for the BWCs and law enforcement agencies would have to pay to store and manage the data generated by BWCs. Would Congress provide grant funding to cover these costs? If not, would this discourage law enforcement agencies from purchasing BWCs for their officers?

- There may also be concerns about whether BWCs could invade citizens' privacy. BWCs could potentially record what officers see when they enter someone's home as well as their interactions with bystanders, suspects, and victims in sometimes stressful situations. The American Civil Liberties Union, which supports the use of BWCs, believes that it is necessary to establish strong policies regarding the use of BWCs so that they do not become another form of public surveillance.98 Law enforcement agencies that outfit their officers with BWCs might also have to conduct an assessment of whether BWCs affect privacy and develop polices about, among other things, which interactions with the public will be recorded, how long the video will be stored, who would have access to it, and whether videos would be distributed to the public.

The researchers at the Center for Evidence-Based Crime Policy also raise concerns about the relative lack of research on BWCs, especially at a time when it appears that many law enforcement agencies are eager to roll out BWC programs. They note that while some BWC-related issues are being studied to a large degree (e.g., the effects of BWCs on the quality of officer-citizen interactions or the effects of BWCs on the use of force by officers), there are other issues upon which research has not largely focused and where more research is needed

- Can BWCs reduce implicit99 or explicit100 bias and differential treatment based on race, sex, age, ethnicity, or other extralegal characteristics?

- Do BWCs have an effect on law enforcement officers' compliance with Fourth Amendment requirements (i.e., concerning illegal search and seizures)?

- Do BWCs affect whether officers engage in proactive contacts (e.g., traffic and pedestrian stops) and do they affect whether officers are likely to make arrests or issue citations in these situations? And if so, what are the implications for both crime control and police-community relations?

- Do BWCs affect whether citizens are willing to call the police, cooperate as victims or witnesses, help with investigations, or comply with officers' commands? What about concerns citizens might have about their privacy regarding be filmed during an interaction with a law enforcement officer?

- Can BWCs facilitate the investigation of critical incidents, officer-involved incidents, or officer-involved shootings or deaths?

- Can BWCs be used to improve training and affect policy changes?

- Do BWCs have an effect on police accountability, supervision, management, and disciplinary systems?

In addition, the researchers also note that there is little research on how BWC programs might affect court proceedings, such as whether BWCs might have an effect on prosecutorial behaviors or practices (e.g., changes in charging patterns, types of plea bargains offered, or witness preparation), evidentiary issues (e.g., would lost footage or failure to record have an effect on proceedings), or the legal effects of failing to tell someone they were being recorded.

Research on BWCs, while more robust than the research on other forms of new law enforcement technology, appears to still be in its infancy. This might raise the issue of whether Congress should support more research on BWC programs before potentially investing millions of dollars to expand BWC use in law enforcement agencies across the country.

Facilitating the Investigation and Prosecution of Excessive Force

The decisions of grand juries in Missouri and New York not to indict the police officers responsible for the deaths of Michael Brown and Eric Garner have raised questions about whether the grand jury system favors police and if the system can hold officers accountable for civilian deaths.101 Some have concerns that because local prosecutors work closely with police officers on cases, they might not be able to objectively evaluate police-involved shootings.102 Policymakers might want to consider ways to use federal authority to promote more accountability for deaths resulting from police officers' actions.

One option Congress could consider is amending 18 U.S.C. Section 242 to remove the requirement that federal prosecutors must show that an officer had the specific intent to deprive someone of his or her civil rights. This could be done by amending Section 242 to employ a "reckless disregard" standard. This would allow DOJ to prosecute not only officers who intentionally violated an individual's constitutional rights, but also those who use force in a reckless manner. This option might help promote a sense of greater police accountability because police-involved shootings could then be more frequently investigated and prosecuted by DOJ. This also may help counteract the perception that police officers are being investigated by their friends and colleagues. However, this option may also raise concerns about state sovereignty. To wit, does Congress want to shift more responsibility for maintaining police accountability from state and local agencies to the federal government?

Another option might be to promote the use of special or independent prosecutors to investigate cases of police-related fatalities. Congress could make it a condition of receiving federal funding that states have a procedure in place whereby the state or local government can appoint a special or independent prosecutor in instances of police-involved shootings. If Congress chooses to pursue this option, it may consider several policy questions

- What event would trigger the appointment of a special prosecutor? Because many excessive force cases are initially investigated internally by the local police department, it could be useful to have a clear mechanism in place to determine when a special prosecutor would be appointed.

- Should such a policy require states to appoint a special prosecutor in all police-involved shooting cases or should the appointing authority have the discretion to decide when to appoint a special prosecutor? Requiring states to appoint a special prosecutor in all cases might reassure the public that an impartial investigation is being conducted; however, it might also be viewed as an undue financial burden on the states.

- How would special prosecutors be chosen: by the governor, the state attorney general, the presiding judge, or someone else?

- From which office would special prosecutors be chosen? They might be appointed from a different locality in the state, from the state attorney general's office, or from the private sector.

Congress may grapple with these and other questions when attempting to alter states' criminal justice systems to promote increased police accountability.

Promoting Community Policing

Community policing is viewed as one potential avenue to repairing relationships between law enforcement agencies and the communities they serve. Congress has already established a grant program to promote community policing: the Community Oriented Policing Services (COPS) program. Under the COPS program, Congress can appropriate funding for grants to state, local, and tribal law enforcement agencies to "hire and train new, additional career law enforcement officers for deployment in community-oriented policing."103

One issue with using the COPS program to promote community policing is that there is no single definition of community policing and the authorizing legislation for the COPS program does not contain a definition of community policing. Two scholars, in their review of trends in policing, note that community policing is "a catchphrase that has been used to describe a potpourri of different strategies" and that "one complication in determining the extent to which [community policing] has transformed policing is determining exactly what it is."104 The COPS Office states that community policing is a "philosophy that promotes organizational strategies that support the systematic use of partnerships and problem-solving techniques to proactively address the immediate conditions that give rise to public safety issues such as crime, social disorder, and fear of crime."105 However, some critics argue that if community policing is only a philosophy, it is nothing more than an "empty shell."106 All of this is to say that if policymakers want to promote community policing, it is not clear exactly what that entails, and before providing grants to law enforcement agencies to promote community policing, policymakers may want to decide what they want community policing to be.

There may be some questions about whether COPS grants convince law enforcement agencies to move toward community policing. During the mid- to late 1990s, the COPS Office awarded billions of dollars in grants for law enforcement agencies to hire officers to engage in community policing.107 However, over this same period of time there was continued growth in use of Special Weapons and Tactics (SWAT) teams by law enforcement agencies nationwide.108 Research on SWAT teams indicates that many law enforcement agencies believe they play an important role in community policing strategies.109 In addition, scholars argue that "community policing" is just a way for law enforcement agencies to present their old ways in a new package. Two scholars note, "[law enforcement agencies] are managing to reconstitute their image away from the citizen-controller paradigm based in the autonomous legal order and towards a more comforting Normal Rockwell image―police as kind, community care-takers."110 They contend that community policing is more about police transforming their image rather than the substance of their work.

The COPS Office notes that the majority of police recruits receive their training in academies with a stress-based military organization style (e.g., a "boot camp") that prepares young recruits for "combat" and emphasizes the crime fighting and action-oriented aspects of policing.111 A stress-based approach to training officers does not always "lend itself to the philosophical underpinnings of community policing, even when there is an effort to incorporate community policing and collaborative problem solving into the curriculum."112 Research on training for law enforcement careers suggests that law enforcement agencies might not be recruiting candidates that would be well-suited for community policing activities. Recruits might be attracted to police work because they want to focus on honing their skills in shooting, driving, and defensive tactics rather than acquiring knowledge about crime causation, diversity, and the law.113 Also, even if recruits are given formal training in the skills needed for community policing, the effect of those lessons might be minimized by the informal lessons recruits learn at the academy or during their first years of service.114 Scholars note, "the informal messages may be so salient that they may counteract the formal curriculum. The new police training may not be fully effective until the [community policing] philosophy is fully integrated into the operating environments of police agencies, their organizational goals, and the larger police culture."115

Congress could promote community policing by continuing to provide funding for COPS hiring grants. However, as the discussion above illustrates, there appear to be some limitations to how much influence COPS grants can have on re-orienting law enforcement agencies toward community policing. Before allocating more funding for COPS hiring grants, policymakers might consider whether there need to be clearer expectations for how law enforcement agencies use the officers hired with the grants, or at least some limitations on COPS-funded officers' activities. Congress could also consider providing funding to the COPS Office to do more training and host seminars on the importance of using community policing practices to try to engender trust between the police and citizens.

Non-legislative Measures

In addition to the legislative measures outlined above, policymakers may also consider ways to use Congress's "soft" power (i.e., non-legislative influence) to bring about improvements in police-community relations. For example, Congress might continue to hold hearings on issues related to police-community relations, racial disparity in the criminal justice system, DOJ's role in assisting law enforcement agencies with adopting more effective policing strategies, or how law enforcement officers use force. Policymakers could continue to give speeches about the importance of improving trust in police and meet with local officials to discuss what they are doing to improve law enforcement services. Policymakers might also consider meeting with community groups to get their views on what, if any, reforms need to take place and to keep them engaged in promoting efforts to reform law enforcement practices.

Non-legislative congressional influence could serve to keep police-community relations in the national spotlight and keep pressure on state and local law enforcement agencies to improve their relationships with the public. To some extent, efforts to change the way that law enforcement officers interact with citizens must come from changes within law enforcement agencies, and these changes might only be brought about through grassroots movements. Congress might be able to support these movements by keeping the issue of citizens' trust in the police in the national consciousness.