Introduction

The Trickett Wendler, Frank Mongiello, Jordan McLinn, and Matthew Bellina Right to Try (RTT) Act of 2017 became federal law on May 30, 2018. Over the preceding five years, 40 states had enacted related legislation. The goal was to allow individuals with imminently life-threatening diseases or conditions to seek access to investigational drugs without the step of procuring permission from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Another goal—held by the Goldwater Institute, which led the initiative toward state bills, and some of the legislative proponents—was focused more on the process: to eliminate government's role in an individual's choice.

The effort to publicize the issue and press for a federal solution involved highlighting the poignant situations of individuals who sought access. For example, in March 2014, millions of Americans heard about the plight of a seven-year-old boy with cancer. He was battling an infection no antibiotic had been able to tame.1 His physicians thought an experimental drug might help.

Because the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) had not yet approved that experimental drug, it was not available in pharmacies. But FDA did have the authority to permit the use of an unapproved drug in certain circumstances—a process referred to as expanded access or compassionate use. For FDA to grant that permission, however, the manufacturer must have agreed to provide the drug. The manufacturer, which was still testing the drug that the boy sought, declined.

Other stories often pointed toward FDA as an obstacle. Until FDA approves a drug or licenses a biologic, the manufacturer cannot put it on the U.S. market.

During this time, Congress faced pressure to act, encouraged by the Goldwater Institute, which framed the issue as one of individual freedom—a right to try. The institute, which news accounts frequently refer to as a libertarian think tank,2 circulated model legislation.3 The bill's preface describes its scope:

A bill to authorize access to and use of experimental treatments for patients with an advanced illness; to establish conditions for use of experimental treatment; to prohibit sanctions of health care providers solely for recommending or providing experimental treatment; to clarify duties of a health insurer with regard to experimental treatment authorized under this act; to prohibit certain actions by state officials, employees, and agents; and to restrict certain causes of action arising from experimental treatment.

After 33 states4 enacted legislation reflecting the Goldwater Institute-provided model bill, in January 2017, legislators introduced a bill (S. 204) designed to address the issue. Their Trickett Wendler, Frank Mongiello, Jordan McLinn, and Matthew Bellina Right to Try Act of 2017—named for several individuals facing amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS, Lou Gehrig's disease) or Duchenne muscular dystrophy—sought to remove what proponents saw as FDA obstacles to patient access.

On May 30, 2018, President Trump signed the bill into law (P.L. 115-176).

This report discusses

- FDA's expanded access program, which many refer to as the compassionate use program, through which FDA allows manufacturers to provide to patients investigational drugs—drugs that have not completed clinical trials to test their safety and effectiveness;

- obstacles—perceived as the result of FDA or manufacturer decisions—to individuals' access to experimental drugs;

- a summary of the provisions in the Right to Try (RTT) Act and how they are meant to ease those obstacles;

- a discussion of selected provisions in the RTT Act and what questions remain unresolved; and

- comments about the broader implications of the RTT Act.

Expanded Drug Access: FDA Authority and Policy Before the Right to Try Act

What Is FDA's Standard Drug Approval Procedure?

In general, a manufacturer may not sell a drug or vaccine in the United States until FDA has reviewed and approved its marketing application. That application for a new drug or biologic includes data from clinical trials as evidence of the product's safety and effectiveness for its stated purpose(s).5

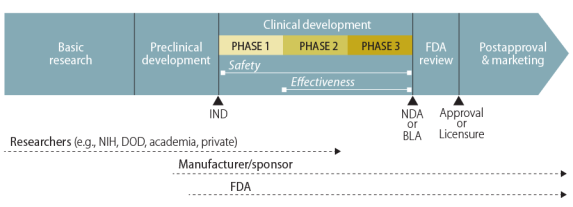

After laboratory and animal studies have identified a potential drug or vaccine, a sponsor, usually the manufacturer, may submit an investigational new drug (IND) application to FDA.6 With FDA permission, the sponsor may then start the first of three major phases of clinical—human—trials. (Figure 1 illustrates the general path of a pharmaceutical product.)

Once the IND application is approved, researchers test in a small number of human volunteers the safety they had previously demonstrated in animals. These trials, called Phase I clinical trials, attempt "to determine dosing, document how a drug is metabolized and excreted, and identify acute side effects."7 If a sponsor considers the product still worthy of investment based on the results of a Phase I trial, it continues with Phase II and Phase III trials. Those trials look for evidence of the product's effectiveness—how well it works for individuals with the particular characteristic, condition, or disease of interest. Phase II is a first attempt at assessing effectiveness and its experience helps to plan the subsequent Phase III clinical trial, which the sponsor designs to be large enough to statistically test for meaningful differences attributable to the drug.

|

|

Source: Created by CRS. Notes: The figure does not show the elements of the path to scale. |

A manufacturer may distribute a drug or vaccine in the United States only if FDA has (1) approved its new drug application (NDA) or biologics license application (BLA) or (2) authorized its use in a clinical trial under an IND. Under standard procedures, individuals outside of the sponsor-run clinical trials do not have access to the investigational new drug. The Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FFDCA), however, permits FDA in certain circumstances to allow access to an unapproved drug or to an approved drug for an unapproved use. One such mechanism is expanded access, commonly referred to as compassionate use, through individual or group INDs.

How Does FDA Regulate Individual IND Applications?

|

Key Expanded Access Source Documents FFDCA §561 (21 U.S.C. §360bbb). Expanded access to unapproved therapies and diagnostics. FFDCA §561A (21 U.S.C. §360bbb-0). Expanded access policy required for investigational drugs. 21 CFR Part 312. Investigational new drug application. FDA, "Guidance for Industry: Expanded Access to Investigational Drugs for Treatment Use—Questions and Answers," June 2016, updated October 2017, http://www.fda.gov/downloads/drugs/guidancecomplianceregulatoryinformation/guidances/ucm351261.pdf. |

The primary route for an individual to obtain an investigational drug is to enroll in a clinical trial testing that new drug.8 However, an individual may be excluded from the clinical trial because its enrollment is limited to patients with particular characteristics (e.g., in a particular stage of a disease, with or without certain other conditions, or in a specified age range), or because the trial has reached its target enrollment number.

Through FDA's expanded access procedure,9 a person, acting through a licensed physician, may request10 access to an investigational drug—through either a new IND or a revised protocol to an existing IND—if11

- a licensed physician determines (1) the patient has "no comparable or satisfactory alternative therapy available to diagnose, monitor, or treat" the serious disease or condition; and (2) "the probable risk to the person from the investigational drug or investigational device is not greater than the probable risk from the disease or condition";

- the Secretary (FDA, by delegation of authority) determines (1) "that there is sufficient evidence of safety and effectiveness to support the use of the investigational drug" for this person; and (2) "that provision of the investigational drug ... will not interfere with the initiation, conduct, or completion of clinical investigations to support marketing approval"; and

- "the sponsor, or clinical investigator, of the investigational drug ... submits" "to the Secretary a clinical protocol consistent with the provisions of" FFDCA Section 505(i) and related regulations.

FDA makes most expanded access IND and protocol decisions on an individual-case basis. Consistent with the IND process under which the expanded access mechanism falls, it considers the requesting physician as the investigator. The investigator must comply with informed consent and institutional review board (IRB) review of the expanded use. The manufacturer must make required safety reports to FDA. FDA may permit a manufacturer to charge a patient for the investigational drug, but "only [for] the direct costs of making its investigational drug available"12 (i.e., not for development costs or profit).

Expanded access could apply outside of the clinical trial arena in these situations:

(1) use in situations when a drug has been withdrawn for safety reasons, but there exists a patient population for whom the benefits of the withdrawn drug continue to outweigh the risks; (2) use of a similar, but unapproved drug (e.g., foreign-approved drug product) to provide treatment during a drug shortage of the approved drug; (3) use of an approved drug where availability is limited by a risk evaluation and mitigation strategy (REMS) for diagnostic, monitoring, or treatment purposes, by patients who cannot obtain the drug under the REMS; or (4) use for other reasons.13

The widespread use of expanded access is limited by an important factor: whether the manufacturer agrees to provide the drug, which—because it is not FDA-approved—cannot be obtained otherwise. FDA does not have the authority to compel a manufacturer to participate.

Expanded Drug Access: Obstacles

Many highly publicized accounts of specific individuals' struggles with life-threatening conditions and efforts by activists influenced public debate over access. Another development was the model bill circulated in 2014 by the Goldwater Institute.14 Examples of public attitudes included news accounts of specific individuals' struggles with life-threatening conditions.

Some found the process of asking FDA for a treatment IND too cumbersome. Others question FDA's right to act as a gatekeeper at all.15 Some point to manufacturers' refusal to provide their experimental drugs. Most critics, therefore, see solutions as within the control of FDA or pharmaceutical companies.

This section lays out key perceived obstacles and issues—both FDA- and manufacturer-related.

FDA-Related Issues

Difficult Process to Request FDA Permission

Have FDA's procedures discouraged patients and their physicians from seeking treatment INDs? For example: Does FDA ask for so much information that physicians or patients do not begin or complete the application? Does the FDA application process take too much time given the urgent need?

In February 2015, FDA issued draft guidance (finalized in June 2016) on individual patient expanded access applications, acknowledging such difficulties.16 It developed a new form that a physician could use when requesting expanded access for an individual patient. It reduced the amount of information required from the physician by allowing reference (with the sponsor's permission) to the information the sponsor had already submitted to FDA in its IND.17 When a patient needs emergency treatment before a physician can submit a written request, FDA can authorize expanded access for an individual patient by phone or email, and the physician or sponsor must agree to submit an IND or protocol within 15 working days.18

Coincident with discussions preceding passage of the RTT Act, FDA had commissioned an independent report on its expanded access program. Citing that report,19 in November 2018, the commissioner announced several actions to improve its program. These include an enhanced webpage to help applicants navigate the application process and establishing an agency-wide Expanded Access Coordinating Committee. Regarding the RTT Act's new pathway to investigational drug access, FDA has established a work group and set up a Right to Try webpage.20

FDA as Gatekeeper

In August 2014, a USA Today editorial called the FDA procedures that patients must follow for compassionate use access "bureaucratic absurdity," "daunting," and "fatally flawed." Echoing much of the criticism that FDA had received regarding the issue, it called for one measure that would "cut out the FDA, which now has final say."21 The solution the editorial proposed involved what proponents term "right-to-try" laws. By January 2018, 39 states had passed right to try laws in the absence of federal legislation.22 These laws were intended to allow a manufacturer to provide an investigational drug to a terminally ill patient if the case met certain conditions:

- the drug has completed Phase I testing and is in a continuing FDA-approved clinical trial;

- all FDA-approved treatments have been considered;

- a physician recommends the use of the investigational drug; and

- the patient provides written informed consent.

The state laws account for anticipated obstacles to the new arrangement. For example, they provide that insurers may, but are not required to, cover the investigational treatment, and that state medical boards and state officials may not punish a physician for recommending investigational treatment. The laws vary on the detail required in the informed consent and liability issues of the manufacturer and the patient's estate.23 However, several experts had suggested that this state law approach is unlikely to directly increase patient access.24 Before passage of the federal RTT Act, analysts raised questions about how federal law (the FFDCA), which required FDA approval of such arrangements, might preempt this type of state law.25 With the federal RTT Act now in place, some legal analysts suggest that the issue of federal preemption of state laws "will likely be determined on a case-by-case basis."26 Second—and also relevant to the federal RTT Act—for a patient who follows FDA procedures, FDA action is not the final obstacle to access. During FY2010 through FY2017, FDA received 10,482 expanded access requests and granted 10,429 (99.5%) of them.27

Before the passage of the RTT Act, several bills were introduced at the federal level in the 113th, 114th, and 115th Congresses.28

Although the stated goal of these laws—allowing seriously ill people to try an experimental drug when other treatments have failed—may be understandable, provisions in the laws may be subject to legal,29 logistical, ethical, and medical obstacles.

Do these laws actually increase such access? Provisions in the federal and state right-to-try laws allow certain patients to obtain—without the FDA's permission—an investigational drug that has passed the Phase 1 (safety) clinical trial stage. A key obstacle to patients' obtaining investigational drugs nonetheless remains: FDA does not have "final say" because it cannot compel a manufacturer to provide the drug.

Manufacturer-Related Issues

Why would a manufacturer not give its experimental drug to every patient who requests it? The manufacturer faces a complex decision. Certainly profit plays a role: companies think about public relations problems and the opportunity costs of limited staff and facility resources, but companies must also consider the available supply of the drug, liability, safety, and whether adverse event or outcome data will affect FDA's consideration of a new drug application in the future.

Available Supply

If a manufacturer has only a tiny amount of an experimental drug, that paucity may limit distribution, no matter what the manufacturer would like to do. Sponsors of early clinical research make small amounts of experimental products for use in small Phase I safety trials, and progressively more for Phase II and III trials. Although one or two additional patients may not cause supply problems, a manufacturer does not know how many expanded access requests it will receive. Investment in building up to large-scale production usually comes only after reasonable assurance that the product will get FDA approval. For a company to redirect its current manufacturing capacity involves financial, logistic, and public relations decisions. A solution—though not immediately effective—might be committing additional resources to increase production.30

Liability

In discussing expanded access, some manufacturers have raised liability concerns if patients report injury from the investigational products.31 In the state right-to-try laws, there are some attempts to protect manufacturers or clinicians from state medical practice or tort liability laws.32 If there are legitimate concerns, Congress could consider acting as it has in past, choosing diverse approaches to protect manufacturers, clinicians, and patients in a variety of situations.33 Whether these concerns become illustrated by court cases and how any issues may be resolved in future laws are beyond the scope of this discussion.34

Limited Staff and Facility Resources

Any energy put into setting up and maintaining a compassionate use program could take away from a company's focus on completing clinical trials, preparing an NDA, and launching a product into the market. While this delay would have bottom-line implications, one CEO, in denying expanded access, portrayed the decision as an equity issue, saying, "We held firm to the ethical standard that, were the drug to be made available, it had to be on an equitable basis, and we couldn't do anything to slow down approval that will help the hundreds or thousands of [individuals]." Pointing to ways granting expanded access might divert them from research tasks and postpone approval, he said, "Who are we to make this decision?"35

Data for Assessing Safety and Effectiveness

By distributing the drug outside a carefully designed clinical trial, it may be difficult, if not impossible, to collect the data that would validly assess safety and effectiveness. Without those data, a manufacturer could be hampered in presenting evidence of safety and effectiveness when applying to FDA for approval or licensure.36

Clinical trials are structured to assess the safety of a drug as well as its effectiveness. The trial design may exclude subjects who are so ill from either the disease or condition for which the drug is being tested or another disease or condition. This allows, among other reasons, the analysis of adverse events in the context of the drug and disease of interest. The patients who would seek a drug under a right-to-try pathway are likely to be very ill and likely to experience serious health events. Those events could be a result of the drug or those events could be unrelated. They would present difficulties both scientific and public relations-wise to the manufacturer. A manufacturer would avoid those risks by choosing to not provide a drug outside a clinical trial.

Disclosure

It is unclear how many people request and are denied expanded access to experimental drugs. This lack of information makes devising solutions to manufacturer-based obstacles difficult. Although FDA reports the number of requests it receives, manufacturers do not (nor does FDA require them to do so). The number of individuals who approach manufacturers is unknown, although some reports suggest that it is much larger than the number of successful requests that then go to FDA. For example, one report indicated that the manufacturer of an investigational immunotherapy drug, which does not have a compassionate use program, received more than 100 requests for it.37

Federal Legislation Before the Right to Try Act

For the past several Congresses, Members have introduced bills with varying approaches to increasing patient access to investigational drugs. Some followed the Goldwater Institute model (to take FDA out of the process) and some proposed requiring manufacturers to publicize their compassionate use policies and decisions or requiring that the Government Accountability Office (GAO) study the patterns of patient requests and manufacturer approvals and denials, barriers to drug sponsors, and barriers in the application process.

Congress enacted two larger bills that each included sections on expanded access: the 21st Century Cures Act (Section 3032, P.L. 114-255) and the FDA Reauthorization Act of 2017 (Section 610, P.L. 115-52).

In December 2016, the 21st Century Cures Act added a new Section 561A to the FFDCA: "Expanded Access Policy Required for Investigational Drugs." It required "a manufacturer or distributor of an investigational drug to be used for a serious disease or condition to make its policies on evaluating and responding to compassionate use requests publicly available."38 In August 2017, the FDA Reauthorization Act of 2017 amended the date by which a company must post its expanded access policies and required the Secretary to convene a public meeting to discuss clinical trial inclusion and exclusion criteria, issue guidance and a report, issue or revise guidance or regulations to streamline IRB review for individual patient expanded access protocols, and update any relevant forms associated with individual patient expanded access. It also required GAO to report to Congress on individual access to investigational drugs through FDA's expanded access program.39

The Trickett Wendler, Frank Mongiello, Jordan McLinn, and Matthew Bellina Right to Try Act of 2017 (S. 204, P.L. 115-176)

On January 24, 2017, Senator Johnson introduced S. 204, the Trickett Wendler Right to Try Act of 2017, and the bill had 43 cosponsors at that time. On August 3, 2017, the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions discharged the bill by unanimous consent. The same day, the Senate passed S. 204, the Trickett Wendler, Frank Mongiello, Jordan McLinn, and Matthew Bellina Right to Try Act with a substantial amendment also by unanimous consent.

On March 13, 2018, Representative Fitzpatrick introduced a related bill, H.R. 5247, the Trickett Wendler, Frank Mongiello, Jordan McLinn, and Matthew Bellina Right to Try Act of 2018, and the bill had 40 cosponsors at that time. On March 21, the House passed the bill (voting 267-149). The House accepted the Senate bill on May 22, 2018 (voting 250-169), and the President signed it into law on May 30, 2018.

This section of the report first summarizes the provisions in the Right to Try Act. It then discusses how those provisions address the obstacles described in the previous section.

Provisions in the Right to Try Act

The Right to Try Act adds to the FFDCA a new Section 561B, Investigational Drugs for Use by Eligible Patients. It has a separate paragraph that is not linked to an FFDCA section to limit the liability to all entities involved in providing an eligible drug to an eligible patient. It concludes with a "Sense of the Senate" section.

The new FFDCA Section 561B has several provisions that mirror many steps in FDA's expanded access program. A major difference is that the new section is designed to exist wholly outside the jurisdiction and participation of FDA. These provisions

- define an eligible patient as one who (1) has been diagnosed with a life-threatening disease or condition, (2) has exhausted approved treatment options and is unable to participate in a clinical trial involving the eligible investigational drug (as certified by a physician who meets specified criteria), and (3) has given written informed consent regarding the drug to the treating physician;

- define an eligible investigational drug as an investigational drug (1) for which a Phase 1 clinical trial has been completed, (2) that FDA has not approved or licensed for sale in the United States for any use, (3) that is the subject of a new drug application pending FDA decision or is the subject of an active investigational new drug application being studied for safety and effectiveness in a clinical trial, and (4) for which the manufacturer has not discontinued active development or production and which the FDA has not placed on clinical hold; and

- exempt use under this section from parts of the FFDCA sections regarding misbranding, certain labeling and directions for use, drug approval, and investigational new drugs regulations;

The new FFDCA Section 561B has provisions that had not been necessary when access had been granted under FDA auspices. These provisions

- prohibit the Secretary from using clinical outcome data related to use under this section "to delay or adversely affect the review or approval of such drug" unless the Secretary determines its use is "critical to determining [its] safety," at which time the Secretary must provide written notice to the sponsor to include a public health justification, or unless the sponsor requests use of such clinical outcome data;

- require the sponsor to submit an annual summary to the Secretary to include "the number of doses supplied, the number of patients treated, the uses for which the drug was made available, and any known serious adverse events"; and

- require the Secretary to post an annual summary on the FDA website to include the number of drugs for which (1) the Secretary determined the need to use clinical outcomes in the review or approval of an investigational drug, (2) the sponsor requested that clinical outcomes be used, and (3) the clinical outcomes were not used.

The act has an uncodified section titled "No Liability," which does not correspond to actions in FDA's expanded access program. It states that, related to use of a drug under the new FFDCA Section 561B,

- "no liability in a cause of action shall lie against ... a sponsor or manufacturer; or ... a prescriber, dispenser, or other individual entity ... unless the relevant conduct constitutes reckless or willful misconduct, gross negligence, or an intentional tort under any applicable State law"; and

- no liability, also, for a "determination not to provide access to an eligible investigational drug."

Discussion of Selected Provisions in the Right to Try Act

Will the RTT Act result in more patients getting access to investigational drugs? Will it ease hurdles for those who would have gone through FDA's expanded use process? This report discusses several provisions in the RTT Act that Congress could consider as it oversees the law's implementation.

Eligible Patients

The RTT Act defines eligibility, in part, as a person diagnosed with a "life threatening disease or condition." That definition differs from many of the state-passed laws, as well as from what FDA preferred: that the definition make clear patients were eligible only if they faced a "terminal illness."40 The commissioner noted that "[many] chronic conditions are life-threatening, but medical and behavioral interventions make them manageable."41 Examples of such diseases or conditions are diabetes and heart disease.

Speaking in support of right to try bills, supporters told of people facing death who, with no alternatives remaining, would be willing to risk an experimental drug that might even hasten their death.42 By not limiting eligibility to those at the end of options, the RTT Act could allow people with chronic conditions to take extreme risks rather than live a normal lifespan with treatments now available. Because of the broad eligibility, manufacturers could see a significant increase in requests.

If a new Congress revisits the RTT Act, Members might consider the definition and clarify what they want for patients and manufacturers.

Informed Consent

The RTT Act makes it mandatory that before eligible patients receive an investigational drug, they give the treating doctor their informed consent in writing—but it does not define "informed consent."

Other right-to-try bills, including the House-passed H.R. 5247, included more specific direction for consent, such as criteria already laid out in 21 CFR Part 50.43 The new law neither provides nor requires the development of such criteria. It thus may weaken patient protections that FDA's expanded use policy provides. The RTT Act also seems to eliminate the requirement that an IRB review the investigational use of a drug.

If Congress decides to revisit RTT, it may seek to create a more explicit informed consent requirement and some outside oversight to reduce the risk to patients either by well-meaning but less knowledgeable physicians or by unscrupulous actors some RTT opponents anticipate.44

Data to FDA

Is a drug effective—does it do what it is meant to do? Is a drug safe—do the potential benefits outweigh the potential risks? Neither of these questions can be discussed without data on what happened to those who used the drug.

Clinical Outcomes

It sometimes takes thousands of patients to establish an accurate evaluation of a drug's safety and effectiveness. Researchers exclude from the clinical trial patients who—for reasons other than the drug's efficacy—may not show evident benefit from the drug. Those are the patients who would get access through the RTT pathway.

The RTT Act appears to protect the drug sponsor: it prohibits the Secretary from using clinical outcome data related to use under this section "to delay or adversely affect the review or approval of such drug." This might make a sponsor more likely to approve the use of its investigational drug under this RTT pathway. The RTT Act, however, includes an exception. It allows FDA to use those data if the Secretary determines their use is "critical to determining [the drug's] safety." If drug sponsors find that this remains an obstacle to their permitting RTT access to investigational drugs, Congress could work with them, FDA, and patient advocacy groups to devise another approach.

Adverse Events

The RTT Act requires the manufacturer to report once a year to the Secretary, including an account of all serious adverse events that occurred in the preceding 12 months. It does not require immediate reporting of adverse events.45

This is less than what FDA requires of sponsors of approved and investigational drugs. All must periodically inform FDA of such events—and immediately if the event is "serious and unexpected."46

An adverse event may not be clearly attributable to a drug. A clustering of such reports, though, could signal FDA that this might be something worth exploring.

If Congress were to reconsider the RTT Act, it could explore with stakeholders—FDA, drug sponsors, and physicians and patients who use the RTT pathway—ways to make data available to advance the goal of developing safe and effective drugs while protecting the legitimate business interests of manufacturers and the access of seriously ill individuals to try risky drugs.

Financial Cost to Patient

FDA's expanded use process permits a manufacturer to charge a patient for the investigational drug, but "only [for] the direct costs of making [it] available."47 That means it cannot charge for development costs or to make a profit.

The RTT Act does not address what a drug manufacturer may charge such patients. Insurers have not announced whether they would pay for the drug—or pay for doctor office visits or hospital stays associated with its use.

Congress might examine that question. It might be useful in assessing the effect of the RTT Act to see whether patients could lose coverage for palliative or hospice care because the investigational drug is a potentially curative treatment.

Liability Protections

Manufacturers see liability costs as an obstacle to providing an investigational drug to patients. The no-liability provision in the RTT Act seems to remove that obstacle. It also seems to leave the patient with no legal recourse.

In the past, Congress has sometimes tried to protect both recipients and the manufacturer from harm (e.g., the National Childhood Vaccine Injury Act of 1986 and the Smallpox Emergency Personnel Protection Act of 2003). In those cases, where Congress felt the public health benefit to the larger group outweighed the smaller risk to some, the federal government accepted responsibility for compensating injured patients and indemnifying manufacturers from lawsuits.48 That has not been the motivating force behind the RTT Act.

Discussions of earlier versions of RTT liability protections raised concerns that they might not fully protect the manufacturer.49 As patients begin using drugs under the RTT Act pathway, it is possible that they will test such protections in the courts. This is yet another issue that Congress might pursue.

Concluding Comments

What role could Congress play now that the RTT Act is law? It could answer three questions at the core of measuring its effect on FDA, drug manufacturers, and patients.

- First: Will more patients get investigational drugs? The RTT Act requires manufacturers to report each year on the number of doses supplied and patients treated as a result of the law. It also reports on what the drugs were used for. It might examine the effect on costs incurred by patients.50 Over time—and perhaps with requesting other data—Congress could determine whether the law has had the effect its sponsors intended.

- Second: Has the law removed the obstacles to access to investigational drugs? While the RTT Act achieves proponents' objective of removing the FDA application step in a patient's quest for an investigational drug, it does not address many of the obstacles—such as a limited drug supply or limits on staff and facility resources—that could lead a manufacturer to refuse access to its drugs. And it is not clear whether it sufficiently deals with the obstacles it does address—use of clinical outcomes data and liability protection. The reporting required by the RTT Act was not designed to answer those questions. But Congress could turn to the Government Accountability Office for help. It could also encourage manufacturers, patient advocates, and FDA to collaborate in the search for answers.

- Third: How will this affect FDA? One news article referred to the RTT Act's "bizarre twist," as FDA must determine its role in implementing a law whose function is to remove FDA from the situation.51 Commissioner of Food and Drugs Gottlieb and Senator Johnson, the sponsor of the Senate bill, have exchanged statements that potentially foretell conflict if FDA issues rules that would limit the law's scope.52 Finally, is the RTT Act a harbinger of reduced authority for FDA? Writing in opposition to the bill, four former FDA commissioners warned that it would "create a dangerous precedent that would erode protections for vulnerable patients."53 That is something future Congresses may choose to address. By trying to help one set of ill patients, does Congress wear down the health of the institution meant to protect the public's health?

The RTT Act concludes with a "Sense of the Senate" section that appears to acknowledge that this legislation offers minimal opportunity to patients. It is explicit in asserting that the new law "will not, and cannot, create a cure or effective therapy where none exists." The legislation, it says, "only expands the scope of individual liberty and agency among patients." The drafters realistically end that phrase with "in limited circumstances."