Introduction

Quite commonly, reports on elementary and secondary school teachers begin with the rather obvious notion that the quality of instruction is critical to student learning. Decades of federal policymaking have been built on the premise that good pre-service preparation is an effective route to quality teaching and, ultimately, improved educational outcomes.1 Current policy continues this approach through provisions in Title II, Part A of the Higher Education Act of 1965 (HEA, P.L. 89-329, as amended).2

HEA Title II-A includes financial support and accountability provisions intended to improve programs that prepare teachers before they reach the classroom. Title II-A consists of two major components: (1) a competitive grant program that supports certain reforms in a small number of programs that prepare prospective teachers, and (2) reporting and accountability provisions that require states to track and report on the quality of all teacher preparation programs within their jurisdiction.

The 115th Congress has already taken steps to consider a reauthorization of the HEA. One comprehensive reauthorization bill, H.R. 4508, which was ordered reported by the House Committee on Education and the Workforce on February 8, 2018, would repeal all provisions in Title II.3 Another comprehensive reauthorization bill introduced by the committee's ranking minority member (H.R. 6543) would amend and extend Title II.4

The authorization of appropriations for Title II-A expired at the end of FY2011 and were extended for an additional fiscal year under the General Education Provisions Act. Along with many HEA programs whose authorizations have lapsed, Title II-A authorities have continued to be funded under a variety of appropriations legislation and continuing resolutions; most recently under P.L. 115-245, which provides full-year FY2019 appropriations for the Department of Education (ED), among other agencies. Congressional action to reauthorize the HEA may continue going forward.

This report provides a description of current programs and provisions in Title II-A and identifies a number of the key issues that may be part of the debate over the reauthorization of the HEA. The report begins with a discussion of the broader context within which this conversation might occur.

Context

Historically, pre-service teacher preparation in the United States has mainly occurred at institutions of higher education (IHEs). Thus, the federal effort in supporting such preparation has largely focused on traditional programs and schools of education housed in IHEs. The recent rise of alternative approaches to traditional teacher preparation programs has presented new challenges to long-standing federal policy in this area, particularly where accountability for program quality is concerned.

Roots of Formal Teacher Training

Since the early part of the 20th century, most teachers in U.S. elementary and secondary schools have been prepared at programs operated by an IHE. Prior to that time, formal teacher training occurred in so-called normal schools, which trained high school graduates to become teachers.5 By the turn of the 20th century, universities began to establish schools and colleges of education, in some cases through the incorporation of normal schools.6

Growth of teacher preparation programs and of schools of education at IHEs occurred with two associated developments: the professionalization of the teacher educator and the formalized split between the study of pedagogy and subject-matter disciplines. While English, science, and history departments stressed the importance of subject-area knowledge for teachers, the new leaders of the teaching profession in schools of education and teacher colleges stressed the importance of courses in pedagogy and passing related tests.7

In recent years, the split between training in the practice of teaching and acquisition of subject-matter expertise has widened with the rise of alternative routes to teacher certification. These alternative approaches to traditional teacher preparation typically rely on candidate's a priori knowledge of the subject they will teach and focus mainly on training for classroom instruction and management.

Current Landscape of Teacher Preparation

Since enactment of the Higher Education Amendments of 1998 (P.L. 105-244), HEA Section 205(d) has required the Secretary of Education to prepare an annual report for Congress and the public on the preparation of teachers in the United States.8 The Secretary's Tenth Annual Report is the most recent and contains data for the 2012-2013 academic year.9 Since publication of that report, select (and less comprehensive) data for subsequent years have been made available online.10

|

Teacher Preparation Programs Versus Providers The Department of Education (ED) defines a teacher preparation program as a state-approved course of study, the completion of which signifies that an enrollee has met all the state's educational and/or training requirements for an initial credential to teach in a K-12 school. Since the time of ED's first annual HEA Title II report on the quality of teacher preparation in 2002, there has been a proliferation of teacher preparation programs tailored to meet the growth of numerous teacher certification specializations. This development has resulted in the presence of multiple programs at single institutions. Thus, the Secretary's 2016 Title II report introduced a new term—"teacher preparation providers"—which are institutions or organizations that offer one or more programs. This allows reporting to distinguish between singular programs within an institution/organization and institutions/organizations that operate multiple programs. |

Providers, Programs, Participants, and Completers

Data available online for the 2015-2016 academic year indicate that 2,106 teacher preparation providers offered 26,459 programs across the 50 states, the District of Columbia, and the U.S. territories and freely associated states.11 That year, these programs enrolled 441,439 teaching candidates and produced 159,598 program completers.

The Secretary's Tenth Annual Report provides the most recent detailed national statistics on teacher preparation (Table 1). In the 2012-2013 academic year, 2,171 teacher preparation providers offered 26,589 programs across the 50 states, the District of Columbia, and the U.S. territories and freely associated states.12 These programs enrolled 499,800 teaching candidates and produced 192,459 program completers.

|

Traditional Versus Alternative Routes to Teaching A teacher preparation program may be either a traditional program or an alternative program, as defined by the state, and may be offered within or outside of an IHE. Alternative route teacher preparation programs primarily serve candidates whom states permit to be the teachers of record in a classroom while participating in the route. They may be within an IHE (referred to as "alternative, IHE-based" providers) or outside an IHE (referred to as "alternative, not IHE-based" providers). For purposes of HEA Title II reporting, each state determines which teacher preparation programs are alternative programs. Traditional teacher preparation programs generally serve undergraduate students who have no prior teaching or work experience and generally lead to at least a bachelor's degree. Some traditional teacher preparation programs may lead to a teaching credential but not to a degree. |

Among the 2,171 teacher preparation providers in the 2012-2013 academic year, 69% (1,497) were traditional providers, 22% (473) were alternative route providers based at IHEs, and 9% (201) were alternative route providers not based at IHEs.13 Among the 26,589 teacher preparation programs that year, 70% (18,514) were traditional teacher preparation programs, 20% (5,325) were alternative route teacher preparation programs based at IHEs, and 10% (2,750) were alternative route teacher preparation programs not based at IHEs.14

Among the 499,800 teacher candidates enrolled in the 2012-2013 academic year, more than 89% (447,116) were enrolled in traditional teacher preparation programs, more than 5% (25,135) were enrolled in alternative route teacher preparation programs based at IHEs, and nearly 6% (27,549) were enrolled in alternative route teacher preparation programs not based at IHEs.15

Table 1. Teacher Preparation Providers, Programs, Enrollment, and Completers by Program Type: Academic Year 2012-2013

|

Providers |

Programs |

Enrollment |

Completers |

|||||

|

Number |

Percent |

Number |

Percent |

Number |

Percent |

Number |

Percent |

|

|

Total |

2,171 |

100 |

26,589 |

100 |

499,800 |

100 |

192,459 |

100 |

|

Traditional |

1,497 |

69 |

18,514 |

70 |

447,116 |

89 |

163,613 |

85 |

|

Alternative, IHE-Based |

473 |

22 |

5,325 |

20 |

25,135 |

5 |

13,296 |

7 |

|

Alternative, Not IHE-Based |

201 |

9 |

2,750 |

10 |

27,549 |

6 |

15,550 |

8 |

Source: U.S. Department of Education, Office of Postsecondary Education, Preparing and Credentialing the Nation's Teachers: The Secretary's Tenth Report on Teacher Quality, Washington, DC, August 2016, https://title2.ed.gov/Public/TitleIIReport16.pdf.

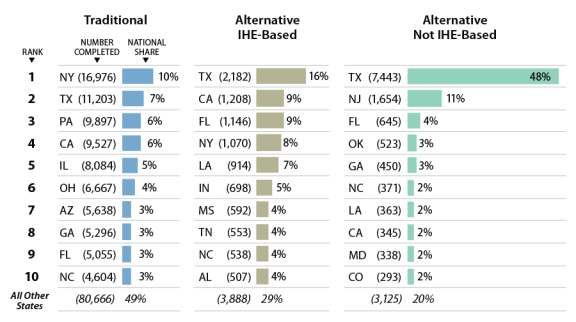

Five states prepared 35% of the 192,849 teacher preparation program completers in the 2012-2013 academic year, led by Texas (20,828 or 11%), New York (18,046 or 9%), California (11,080 or 6%), Pennsylvania (10,372 or 5%), and Illinois (8,534 or 4 %). Figure 1 displays the top 10 states for teacher preparation program completion by program type. New York led the nation in traditional teacher preparation program completion, accounting for 10% of all individuals who completed that type of program. Texas led the nation in completers of alternative routes, accounting for 16% of individuals completing an alternative route based at an IHE and 48% of those completing an alternative route not based at an IHE.16

Other Highlights from the Title II Reporting System

The Secretary's Tenth Annual report reveals a number of interesting aspects of teacher preparation in the United States. Highlights include the following:

- The typical traditional preparation program requires 100 hours of supervised clinical experience and 600 hours of student teaching, while alternative route programs do not require such training.17

- The two largest traditional teacher preparation programs enroll over 30,000 prospective teachers, and both are online programs: Grand Canyon University and the University of Phoenix. This is about 10 times the number of candidates who are enrolled at the next 10 largest programs combined.18

- The large majority of enrollees in teacher preparation programs are white, non-Hispanic; such students comprise 74% of enrollees at traditional programs, 65% at alternative programs based at an IHE, and 59% at alternative programs not based at an IHE.19 Comparable figures for African-American enrollees are 18%, 16%, and 9%.

- The most common subject area of program completion in traditional programs is elementary education (42%), followed by special education (16%), early childhood education (13%), English/language arts (9%), and mathematics (7%).20 Alternative program completion follows a similar pattern.

- The national average scaled score was 14 percentage points above the average cut score: 74.4% versus 60.2%.21 Over 95% of candidates who took a state assessment passed the test.22

HEA Title II, Part A

Title II-A of the HEA has two components: (1) a competitive grant program that provides funds to support the types of programs that Congress has identified as models to be replicated, and (2) reporting and accountability provisions that require the reporting of data on program characteristics, state standards for teacher licensing and certification, and information on the quality of teacher preparation.

Teacher Quality Partnerships

Title II-A of the HEA authorizes the Teacher Quality Partnership (TQP) program, which funds competitive grants to eligible partnerships involved in teacher preparation. According to the statute, the purpose of the TQP program is to improve the quality of prospective and new teachers by improving the preparation of prospective teachers and enhancing professional development activities for new teachers.

The TQP program supports traditional pre-baccalaureate or fifth-year teacher preparation programs as well as teacher residency programs. In addition, it provides extra grant funding to support school leadership activities performed by TQP grantees. Each of these approaches is described in greater detail below. The TQP program has received annual appropriations in recent years of about $42 million, which supports grants to about two dozen partnerships.

Among awarded TQP projects, roughly 30% are pre-baccalaureate/fifth year programs, 48% are residency programs, and 23% are of both types.23 Four teacher preparation programs were awarded a TQP grant in FY2016; 24 grants were awarded in FY2014, 12 were awarded in FY2010, and 28 were awarded in FY2009. No awards were made between FY2011 and FY2013.24

To be eligible for a TQP award, a partnership must include the following:

- a high-need local educational agency that includes either (1) a high-need school (or a consortium of high-need schools), or (2) a high-need early childhood education program;

- a partner institution of higher education;

- a school, department, or program of education within the partner institution; and

- a school or department of arts and sciences within the partner institution.25

TQP grantees are required to match 100% of their award amount with non-federal funds and coordinate their activities with other federally funded programs such as the Teacher Quality State Grants and the Teacher Incentive Fund (under Title II of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act).

Pre-baccalaureate Preparation

Grants are provided to implement a wide range of reforms in teacher preparation programs and, as applicable, preparation programs for early childhood educators. These reforms may include the following, among other things:

- implementing curriculum changes that improve and assess how well prospective teachers develop teaching skills;

- using teaching and learning research so that teachers implement research-based instructional practices and use data to improve classroom instruction;

- developing a high-quality and sustained pre-service clinical education program that includes high-quality mentoring or coaching;

- creating a high-quality induction program for new teachers;

- implementing initiatives that increase compensation for qualified early childhood educators who attain two-year and four-year degrees;

- developing and implementing high-quality professional development for teachers in partner high-need LEAs;

- developing effective mechanisms, which may include alternative routes to certification, to recruit qualified individuals into the teaching profession; and

- strengthening literacy instruction skills of prospective and new elementary and secondary school teachers.

Teaching Residencies

Grants are provided to develop and implement teacher residency programs that are based on models of successful teaching residencies and that serve as a mechanism to prepare teachers for success in high-need schools and academic subjects. Grant funds must be used to support programs that provide

- rigorous graduate-level course work to earn a master's degree while undertaking a guided teaching apprenticeship,

- learning opportunities alongside a trained and experienced mentor teacher, and

- clear criteria for selecting mentor teachers based on measures of teacher effectiveness.

Programs must place graduates in targeted schools as a cohort in order to facilitate professional collaboration. Programs must also provide members of the cohort with a one-year living stipend or salary, which must be repaid by any recipient who fails to teach full time for at least three years in a high-need school and subject or area.

School Leadership

Grants are provided to develop and implement effective school leadership programs to prepare individuals for careers as superintendents, principals, early childhood education program directors, or other school leaders. Such programs must promote strong leadership skills and techniques so that school leaders are able to

- create a school climate conducive to professional development for teachers,

- understand the teaching and assessment skills needed to support successful classroom instruction,

- use data to evaluate teacher instruction and drive teacher and student learning,

- manage resources and time to improve academic achievement,

- engage and involve parents and other community stakeholders, and

- understand how students learn and develop in order to increase academic achievement.

Grant funds must also be used to develop a yearlong clinical education program, a mentoring and induction program, and programs to recruit qualified individuals to become school leaders.

Teacher Preparation Program Accountability

In addition to authorizing the TQP program, Title II (Section 205) of the HEA also includes provisions meant to hold teacher preparation programs accountable. Under these provisions, states and IHEs that operate teacher preparation programs are required to report information on the performance of their programs. States must do so as a condition for receiving HEA funds. IHEs must do so if they enroll students receiving federal assistance under the HEA.

IHEs must issue report cards to the state and to the general public. States must issue report cards to ED and to the general public. ED is required by the HEA to use state-reported information to issue an annual report on teacher qualifications and preparation in the United States. Much of the information presented in the "Context" section of this report was derived from the Title II reporting system authorized in Section 205.

Section 207 of the HEA further requires states to establish criteria to evaluate teacher preparation programs, report the results of these evaluations for traditional and alternative route programs, and identify programs determined to be low-performing or at risk of being classified as low-performing. In 2014, the two most common criteria used by states to evaluate program quality were indicators of teaching skill (46 states) and pass rates on state credentialing assessments (41 states).26 Less commonly used criteria reported by states included improving student academic achievement (31 states), raising standards for entry into the teaching profession (29 states), increasing professional development opportunities (25 states), and increasing the percentage of highly qualified teachers (23 states).

In 2014, 12 states and Puerto Rico reported teacher preparation programs that were low-performing or at-risk of low performance (at-risk). Of the 46 states and jurisdictions that did not identify any programs as low-performing or at-risk in 2014, 30 of those states and jurisdictions have never identified any programs as being low-performing or at-risk. A total of 45 programs were classified as low-performing or at-risk in 2014. Programs identified as low-performing or at-risk represented less than 3% of the total number of teacher preparation programs reported in 2014.

Legislative Action

On February 8, 2018, the House Committee on Education and the Workforce ordered reported the Promoting Real Opportunity, Success, and Prosperity through Education Reform Act (H.R. 4508).27 Approved on a party-line vote, H.R. 4508 would make numerous amendments to the HEA, including the repeal of all current provisions in Title II.28

The ranking member of the committee introduced the Aim Higher Act (H.R. 6543) on July 26, 2018. H.R. 6543 is also a comprehensive HEA reauthorization bill. It would retain and make amendments to current Title II provisions. These amendments include (1) changes to the TQP program (e.g., residencies would be for teachers or principals and grantees would be able to receive a second grant as long as the award's use does not mirror that of the first grant); (2) expansion of accountability provisions for institutions (e.g., report cards would have to be submitted by any preparation entity (not just IHEs) that receives any federal funds—not just HEA funds); (3) changes to accountability for states (e.g., criteria for designation of low-performing and at-risk programs would have to be developed with stakeholders); and (4) expansion of accountability for states (e.g., report cards would have to be submitted by states in order to receive funds under HEA and ESEA Title II; current law only refers to HEA funds).

During the 115th Congress, the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions has held several hearings on HEA reauthorization, but has yet to introduce a bill that would amend Title II.

On March 27, 2017, the President signed a resolution of congressional disapproval (P.L. 115-14) nullifying regulations that had been issued in October 2016.29 The new regulations would have retained current reporting and accountability requirements and added three main elements: (1) clearer guidance on what constitutes a provider versus a program, (2) new post-program completion measures, and (3) additional penalties for poor performance.30

Reauthorization Issues

Congress may continue to consider legislation that would reauthorize the HEA, including the provisions in Title II. Some of the issues that may receive consideration during this process include the following:

- the appropriate role for the federal government to play in supporting innovations and reforms for teacher preparation programs;

- the optimal mix of TQP authorized activities such as support for clinical practice, induction, mentoring, and pre-service assessment; and

- the extent to which current reporting and accountability provisions encourage program quality.

Some argue that the current federal role in supporting teacher preparation is far too limited and that the current TQP program primarily amounts to supporting demonstration projects. This perspective asserts that a lot is known about what good teacher preparation looks like and that the federal role should be greatly expanded to support quality programs broadly. On the other hand, others argue that responsibility for teacher training should remain a state, local, and training institution endeavor and that the federal government should have no role in the support of standards for teacher preparation.

In between these views, there is debate over the optimal mix of activities currently supported under the TQP program. Those who favor traditional routes to teaching would often like to see greater support for enhancements to those programs, including support for supervised clinical practice and assessments that must be passed prior to becoming a teacher. Those favoring alternative routes often want fewer restrictions on TQP partners (i.e., allowing nonprofit organizations to serve as primary, not just supplemental, partners) and want more emphasis placed in the TQP program on in-service supports such as induction and mentoring for teachers.

Some argue for the expansion of federal policy around program quality and that current reporting and accountability provisions do not adequately hold teacher preparation programs to high standards. They cite as evidence the fact that less than 3% of programs have been identified as being low-performing and that three-fifths of the states have never identified a program in this manner. Some of those in favor of greater accountability want to see program evaluations based on outcome measures that are ultimately tied to student performance. On the other hand, others maintain that such accountability requirements should not be instituted at the federal level and that current reporting requirements already pose an unnecessary burden on state and local administrators.