Introduction

Congressional commissions are entities established by Congress to provide advice, make recommendations for changes in public policy, study or investigate a particular problem or event, or perform a specific duty.1 Generally, commissions may hold hearings, conduct research, analyze data, investigate policy areas, and/or make field visits as they perform their duties. Most commissions complete their work by delivering their findings, recommendations, or advice in the form of a written report to Congress. For example, the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States was created to "examine and report upon the facts and causes relating to the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001," and to "investigate and report to the President and Congress on its findings, conclusions, and recommendations for corrective measures that can be taken to prevent acts of terrorism," among other duties.2 The commission ultimately submitted a final report to Congress and the President containing its findings and conclusions, along with 48 policy recommendations.3

This report begins by examining the statutory lifecycle of congressional commissions, including common deadlines that define major milestones and mandate certain commission activities. Next, the report describes the language commonly found in commission legislation, including commission establishment, appointments, duties, powers, rules and procedures, staff, and funding. Specifically, this report provides illustrative examples of statutory language, discusses different approaches used in previous commission statutes, and analyzes possible advantages or disadvantages of different choices in commission design.

This report focuses on congressional commissions created by statute and does not address entities created by the President or other nonstatutory advisory bodies.4

Cataloging Congressional Commissions

While no formal definition exists, for the purposes of this report a congressional commission is defined as a multimember independent entity that (1) is established by Congress, (2) exists temporarily, (3) serves in an advisory capacity, (4) is appointed in part or whole by Members of Congress, and (5) reports to Congress. This definition differentiates a congressional commission from a presidential commission, an executive branch commission, or other bodies with "commission" in their names, while including most entities that fulfill the role commonly associated with commissions: studying policy problems and reporting findings to Congress.

This report analyzes statutory language used between the 101st Congress (1989-1990) and the 115th Congress (2017-2018) to establish congressional commissions. To identify commissions established during this time period, a Congress.gov database search was performed for enacted legislation between the 101st Congress and the 115th Congress.5 Each piece of legislation returned was examined to determine if (1) the legislation established a commission, and (2) the commission was a congressional commission as defined by the five criteria above. If the commission met the criteria, its name, public law number, Statutes-at-Large citation, and date of enactment were recorded. This approach identified 110 congressional commissions established by statute since 1989.

Statutory Lifecycle of Congressional Commissions

A congressional commission is commonly provided a series of deadlines that define major milestones in its statutory lifecycle. The overall amount of time provided to a commission to complete its work may vary substantially depending on how deadlines are constructed.

Although the number and type of deadlines provided to commissions may vary, statutory deadlines are commonly provided for

- the appointment of the commission members;

- the commission's first meeting;

- submission of any interim report(s) that may be required;

- submission of the commission's final work product(s); and

- commission termination.

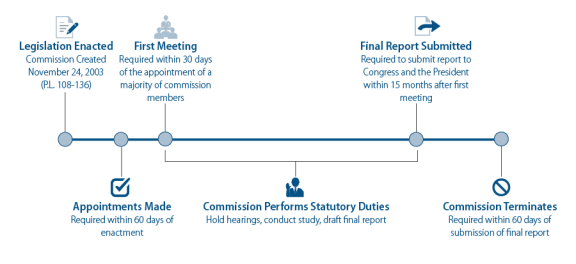

For example, Figure 1 visualizes the amount of time statutorily provided to a commission to complete its tasks. Using the Veterans' Disability Benefits Commission as an example, Figure 1 shows the statutory deadlines for the appointment of commissioners, its first meeting, issuance of its final report, and termination. The amount of time provided for each of the above milestones is fairly typical of commission statutes.

|

Figure 1. Example of the Statutory Lifecycle of a Congressional Commission Veterans' Disability Benefits Commission |

|

|

Source: P.L. 108-136. |

Deadline for Appointments

Commission statutes commonly contain a deadline by which appointments to the commission must be made. As shown in Figure 1, for example, the statute establishing the Veterans' Disability Benefits Commission provided 60 days from enactment for appointments to be made.

For commissions established since the 101st Congress, the amount of time provided for appointments has ranged from 30 days to 1 year. In most cases, appointments are required to be made within some period of time following enactment of legislation creating the commission. A smaller number of statutes tie appointment deadlines to the commission receiving appropriations. For example, appointments to the National Commission on Manufactured Housing were required to be made "not later than 60 days after funds are provided" for the commission.6 Regardless of whether the deadline is tied to the commission's enactment or the provision of funds, 60 days is the median amount of time provided for appointments for the 110 commissions analyzed here.

Deadline for First Meeting

Approximately half of commission statutes identified since the 101st Congress direct that the commission's first meeting be held by a particular deadline. As displayed in Figure 1, the Veterans' Disability Benefits Commission was instructed to hold its initial meeting within 30 days of the appointment of a majority of its members. Similar to appointment deadlines, deadlines for initial meetings are commonly tied to another event. Most often, the first meeting is required to occur within some period of time following the appointment of commission members (either the appointment of all members,7 a majority of members,8 or some other number of members)9. In such cases, the median amount of time provided has been 30 days from the appointment of members.

Instead of linking a commission's first meeting to the appointment of commission members, several commissions have instead been directed to hold an initial meeting within some period of time following the commission's establishment. In these cases, the median amount of time provided to the commissions analyzed has been 90 days from establishment of the commission.

Deadline for Final Report

Nearly all commission statutes include a deadline for the submission of a final report. The amount of time provided for final report submission varies substantially. Some commissions, such as the National Commission on the Cost of Higher Education, have been given less than six months to submit their final report to Congress.10 Other commissions, such as the Antitrust Modernization Commission, have been given three or more years to complete their work product.11 The Veterans' Disability Benefits Commission was provided 15 months from its initial meeting to submit a final report, as shown in Figure 1.

For commissions identified since the 101st Congress, the median amount of time provided to submit a final report is approximately 1.4 years, although this period of time may be measured from different starting points. Most commission statutes tied the deadline for final report submission to one of the following events:

- the date of the commission's first meeting;

- enactment of legislation creating the commission;

- appointment of commission members; or

- a specific calendar date.12

The overall length of time granted to a congressional commission for the completion of its final work product is arguably one of the most important decisions when designing a commission. If the commission is given a short amount of time, the quality of its work product may suffer or the commission may not be able to fulfill its statutory mandate. Policymakers may also wish to consider the amount of time necessary for "standing up" a new commission; the appointment of commission members, recruitment of staff, arrangement of office space, and other logistical matters may require six months or more from the date of enactment of commission legislation.

On the other hand, longer deadlines may undercut one of the primary goals of a commission: the timely production of expert advice on a current policy matter. If legislators seek to create a commission to expeditiously address a pressing policy problem, a short deadline may be appropriate. Shorter deadlines may also reduce the overall cost of the commission.

Deadline for Commission Termination

Congressional commissions are usually statutorily mandated to terminate. As with other statutory deadlines, termination dates for most commissions are usually linked to a fixed period of time after either the enactment of the commission statute, the selection of members, or the date of submission of the commission's final report. A smaller number of commission statutes establish a specific calendar date as the deadline for termination. As shown in Figure 1, the Veterans' Disability Benefits Commission was instructed to terminate 60 days after the submission of its final report.13

Linking Deadlines to Specific Events

Statutory deadlines can help ensure that an activity is performed within a desired timeframe. However, the amount of time provided to a commission to perform any particular activity depends on how the particular deadline is established.

While a deadline may be established to require a commission to perform some action by a particular calendar date, commission deadlines are more commonly tied to some other event in the commission's lifecycle, such as enactment, appointment of commissioners, or issuance of a final report. The decision to specify a particular calendar date as a deadline, or to instead tie the deadline to another event, can have a significant effect on the time provided to the commission to carry out its functions.

For instance, legislation requiring a commission to produce a final report by a specific calendar date may ensure delivery of the report at a predictable time. However, the actual amount of time the commission will have to create the report will differ depending on a variety of factors, including the date the legislation is enacted, or the time needed to appoint commission members and hire commission staff. If a commission must submit a report by a specified calendar date, any delays (including in the enactment of the legislation, or "standing up" the commission) would have the practical effect of reducing the amount of time provided to the commission to perform its duties. Linking the final report deadline to a flexible date, such as the first meeting or the appointment of members, will often provide a more predictable amount of time for the commission to complete its work. Tying a commission's final report to a flexible date, however, may delay the actual calendar date of the submission of the final report. It may also reduce the incentive for the commission to take earlier steps, such as conducting an initial meeting, in an expeditious manner.

Commission Structure

Policymakers face a number of choices when designing a commission. Commission statutes frequently include sections that

- establish the commission and state its mandate;

- provide a membership structure and authority for making appointments;

- outline the commission's duties;

- grant the commission certain powers;

- define any rules of procedure;

- address hiring of commission staff; and

- prescribe how the commission will be funded.

A variety of options are available for each of these decisions. The following sections of the report discuss the above-listed components of commission legislation, along with subissues relevant to each. Legislators can tailor the composition, organization, and working arrangements of a commission based on particular congressional goals. The following sections provide illustrative examples of statutory language, discuss potential alternative approaches, and analyze possible advantages or disadvantages of different choices in commission design.

Establishment and Mandate

A commission's establishment is generally prescribed in a brief introductory paragraph, often with a single sentence. For instance, the Western Hemisphere Drug Policy Commission was established according to the following statutory language:

There is established an independent commission to be known as the "Western Hemisphere Drug Policy Commission" (in this title referred to as the "Commission").14

In some instances, this section will further specify that the commission is "established in the legislative branch." This can potentially resolve confusion on the commission's administrative location, especially if members are appointed by both legislative and executive branch officials. For commissions not specifically established in the legislative or executive branch, the manner in which the members of the commission are appointed may determine the commission's legal status.15 A commission with a majority of appointments made by the President may be treated as an executive branch entity for certain purposes. If a majority of appointments are made by Members of Congress, it may be treated as a legislative branch entity.

A bill creating a commission will sometimes provide congressional "findings" that demonstrate congressional intent and provide a justification for creating the panel. For example, the Commission on Protecting and Reducing Government Secrecy statute included eight specific findings related to the scope and cost of Cold War-era secrecy programs that prompted the commission's creation.16

In other cases, legislation creating commissions may simply include a short "purpose" section describing the justification for the commission, in lieu of a longer "findings" section. The United States Commission on North American Energy Freedom, for example, was provided the following brief statutory purpose:

The purpose of this subtitle is to establish a United States commission to make recommendations for a coordinated and comprehensive North American energy policy that will achieve energy self-sufficiency by 2025 within the three contiguous North American nation area of Canada, Mexico, and the United States.17

Commission Membership

Advisory commissions can have a variety of membership structures. Commission designers commonly face decisions that involve how many members the commission should have, how members will be appointed, whether to require a deadline for making appointments, whether to require that members possess particular qualifications, whether to require a particular partisan balance, how to address terms and vacancies, and whether (or how much) to compensate commission members.

Size

The number of members who statutorily serve on congressional commissions varies significantly. The median size of the 110 identified commissions analyzed was 12 members, with the smallest commission having 5 members and the largest having 33 members.

Larger commissions have the potential advantage of surveying a wider range of viewpoints, arguably allowing the commission to produce a more comprehensive final report. A large commission may also aid the chances of legislative success of any policy recommendations a commission must make, especially if the size allows for a greater number of interests to be represented through the commission appointment process. Small commissions, however, likely enjoy efficiency advantages in coordination, completing work products, and conducting hearings and meetings. In addition, overall commission costs may be lower for small commissions, particularly if commission members receive compensation. Smaller commissions may also incur fewer travel and other expenses.

Appointment Methods

Appointments to commissions have been structured in a variety of ways. A wide range of officials have been provided the authority to recommend, appoint, or serve as a member of a commission. Most often, appointments are made through some combination of several methods, including the following:

- Members of the commission are appointed by selected officials, such as congressional leaders, committee leaders, the President, or Cabinet officials.

- Members of the commission are appointed by selected officials, in concert with other officials.18

- Members of the commission are specific individuals, designated by statute.

Examples of each of the aforementioned appointment methods can be found in Table 1. The first entry in Table 1 demonstrates the most common type of appointment method found in commission statutes: where selected leaders are provided authority to name individuals to serve on the commission. While the Commission on the Abolition of the Transatlantic Slave Trade provided authority to congressional leaders from both chambers, appointments to commissions in this manner have also been made by the President,19 Cabinet secretaries,20 the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court,21 and state officials,22 among others, in addition to congressional appointments. Approximately 82% of identified commissions provided for one or more appointments in this manner.

The second entry in Table 1, the Commission on Wartime Contracting, shows another common method of appointment: members of the commission were appointed by selected officials, in concert with other officials. In this instance, Members of House and Senate leadership were required to consult with relevant House or Senate committee chairpersons, while the President was required to consult with the Secretary of Defense and Secretary of State prior to making his appointments. Approximately 53% of identified commissions provided for one or more appointments to be made by officials in concert with other officials.23

The third example in Table 1, the Thomas Jefferson Commemoration Commission, shows a somewhat less common appointment structure, where the statute designated 10 specific officials (or their designees) to serve on the commission. The statute directly names the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, the Librarian of Congress, the Archivist of the United States, and selected congressional leaders, among others, to the commission. Approximately 17% of identified commissions provided for one or more individuals directly designated to serve as a member.

|

Commission Name and Citation |

Statutory Language Related to Appointment Authority |

|

Commission on the Abolition of the Transatlantic Slave Trade P.L. 110-183, Section 4, 112 Stat. 607 |

The Commission shall be composed of nine members, of whom— (i) three shall be appointed by the Speaker of the House of Representatives; (ii) two shall be appointed by the majority leader of the Senate; (iii) two shall be appointed by the minority leader of the House of Representatives; and (iv) two shall be appointed by the minority leader of the Senate. |

|

Commission on Wartime Contracting P.L. 110-181, Section 841(b), 112 Stat. 231 |

The Commission shall be composed of 8 members, as follows: (A) 2 members shall be appointed by the majority leader of the Senate, in consultation with the Chairmen of the Committee on Armed Services, the Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs, and the Committee on Foreign Relations of the Senate. (B) 2 members shall be appointed by the Speaker of the House of Representatives, in consultation with the Chairmen of the Committee on Armed Services, the Committee on Oversight and Government Reform, and the Committee on Foreign Affairs of the House of Representatives. (C) 1 member shall be appointed by the minority leader of the Senate, in consultation with the Ranking Minority Members of the Committee on Armed Services, the Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs, and the Committee on Foreign Relations of the Senate. (D) 1 member shall be appointed by the minority leader of the House of Representatives, in consultation with the Ranking Minority Member of the Committee on Armed Services, the Committee on Oversight and Government Reform, and the Committee on Foreign Affairs of the House of Representatives. (E) 2 members shall be appointed by the President, in consultation with the Secretary of Defense and the Secretary of State. |

|

Thomas Jefferson Commemoration Commission P.L. 102-343, Section 5, 106 Stat. 916 |

The Commission shall be composed of 21 members, including— (A) the Chief Justice of the United States or such individual's delegate; (B) the Librarian of Congress or such individual's delegate; (C) the Archivist of the United States or such individual's delegate; (D) the President pro tempore of the Senate or such individual's delegate; (E) the Speaker of the House of Representatives or such individual's delegate; (F) the Secretary of the Interior or such individual's delegate; (G) the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution or such individual's delegate; (H) the Secretary of Education or such individual's delegate; (I) the Chairman of the National Endowment for the Humanities or such individual's delegate; (J) the Executive Director of the Thomas Jefferson Memorial Foundation or such individual's delegate; and (K) 11 citizens of the United States who are not officers or employees of any government, except to the extent they are considered such officers or employees by virtue of their membership of the Commission. … The individuals referred to in paragraph (1)(K) shall be appointed by the President. |

Source: P.L. 110-183; P.L. 110-181; P.L. 102-343.

A commission statute may provide for appointments according to a single method or multiple methods. Similarly, appointment authority may be provided to a small number or a large number of selected leaders or officials. Providing appointment authority to a wider range of individuals may have the advantage of generating additional "buy-in" from selected leaders. On the other hand, providing appointment authority to a greater number of individuals may increase the risk of delays in completing the appointment process.

Qualifications

Commission statutes may include qualifications or restrictions on who may be appointed to a commission. Qualifications on appointments may be designed to ensure that the commission is made up of experts, is representative of particular groups, or that a range of viewpoints may be heard.

Legislation creating commissions frequently specifies that individuals appointed to the commission should possess certain substantive qualifications, such as experience in a particular field or expertise in a relevant policy matter. For example, the act creating the National Commission on the Future of the Army instructed that

[i]n making appointments under this subsection, consideration should be given to individuals with expertise in national and international security policy and strategy, military forces capability, force structure design, organization, and employment, and reserve forces policy.24

In other cases, Congress may choose qualifications designed to ensure the representation of particular groups that are relevant to the commission's purpose. The statute establishing the Veterans' Disability Benefits Commission, for instance, required the appointment of a certain number of decorated veterans.25 The statute establishing the Commission on Indian and Native Alaskan Health Care required the appointment of "[n]ot fewer than 10" Indians or Native Alaskans to serve on the commission.26

Congress may also choose qualifications to ensure that a commission contains a wide range of viewpoints. A commission may be designed to review a policy issue that affects a variety of interests or economic sectors, and legislators may place qualifications on appointments to ensure each interest is represented. For instance, the statute creating the Motor Fuel Tax Enforcement Advisory Commission mandated the appointment of a certain number of individuals to represent the interests of highway construction, fuel distribution, state tax administration, state departments of transportation, and relevant federal agencies, among other interests.27 Similarly, the act creating the Commission on Long-Term Care required the following:

The membership of the Commission shall include individuals who—

(A) Represent the interests of—

(i) Consumers of long-term services and supports and related insurance products, as well as their representatives;

(ii) Older adults;

(iii) Individuals with cognitive or functional limitations;

(iv) Family caregivers for individuals described in clause (i), (ii), or (iii);

(v) The health care workforce who directly provide long-term services and supports;

(vi) Private long-term care insurance providers

(vii) Employers;

(viii) State insurance departments; and

(ix) State Medicaid agencies;

(B) Have demonstrated experience in dealing with issues related to long-term services and supports, health care policy, and public and private insurance; and

(C) Represent the health care interests and needs of a variety of geographic areas and demographic groups.28

Qualifications or restrictions placed on appointments may help ensure that the commission is populated with genuine experts in a policy area, is representative of particular groups or sectors, or is made up of members with a wide range of viewpoints. This may help improve the commission's final work product, increase its stature and credibility, ensure that the desired range of voices can be heard during commission deliberations, or help obtain broader acceptance of the commission's recommendations or findings.

On the other hand, placing qualifications on appointments has the effect of limiting the degree of autonomy provided to those responsible for making appointments. Additionally, the specificity of the language used to establish qualifications may affect whether the qualification achieves its intended goal. If the language establishing qualifications is too precise, certain individuals who might be valuable members of the commission may be excluded from consideration. Conversely, if qualification provisions are too vague, they may be difficult or impossible to enforce, and consequently less likely to meaningfully restrict the appointment of any potential candidate.

Partisan Balance

Among the 110 commissions analyzed here, most have been structured to be bipartisan. A small number of these were designed to have a perfectly even split between the parties. Typically, commissions are structured to be bipartisan by dividing commission appointment authority between Members of the majority and minority parties in the House and Senate. A smaller number of commission statutes ensure bipartisanship by detailing the partisan breakdown of individual commission members. For instance, P.L. 104-275 established a 12-member Commission on Servicemembers and Veterans Transition Assistance, and specified that "[n]ot more than seven of the members of the Commission may be members of the same political party."29 The latter approach, directly specifying or limiting the partisan composition of commission membership, is less common and likely more difficult to enforce; determining the political affiliation of some potential members, who may have no official affiliation with a party (through voter registration, for example), may not be possible. Overall, approximately 74% of identified commissions required some level of bipartisanship in the appointment process.

Bipartisan arrangements may make congressional commissions' findings and recommendations more politically balanced. A bipartisan membership may also lend additional credibility to a commission's recommendations, both within Congress and among the public. A commission that is perceived as partisan may have greater difficulty generating interest and support among the public and gathering the necessary support in Congress.

In some cases, bipartisanship may arguably impede a commission's ability to complete its mission; in situations where a commission is tasked with studying potentially controversial or partisan issues, the appointment of an equal number of commissioners by both parties may result in a situation where the commission's activities are stymied, with neither side able to garner a majority to take action.

Terms and Vacancies

Because most advisory commissions are designed to last only for a set period of time, appointments are usually made for the life of the commission. Many statutes note this explicitly,30 though some simply make no mention of appointment terms.

A smaller number of commissions have been created to endure for longer periods of time, and have established term limits for appointees. For instance, the statute creating the Defense Base Closure and Realignment Commission reads as follows:

(d) Terms.—

(1) Except as provided in paragraph (2), each member of the Commission shall serve until the adjournment of Congress sine die for the session during which the member was appointed to the Commission.

(2) The Chairman of the Commission shall serve until the confirmation of a successor.31

Similarly, the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom was originally designed to last for four years and established appointments with two-year terms:

(c) Terms.—The term of office of each member of the Commission shall be 2 years. Members of the Commission shall be eligible for reappointment to a second term.32

In the majority of cases, commission statutes provide that any vacancies on the commission "shall be filled in the same manner as the original appointment." The statute creating the Defense Base Closure and Realignment Commission, which provided for term-limited commissioners, further specified the term for any individual who was appointed to fill a vacancy:

A vacancy in the Commission shall be filled in the same manner as the original appointment, but the individual appointed to fill the vacancy shall serve only for the unexpired portion of the term for which the individual's predecessor was appointed.33

Expenses and Compensation of Commission Members

Travel Expenses

Most statutorily created congressional commissions have not compensated their members; a majority, however, have provided for reimbursement of expenses directly related to the service of commission members, such as travel costs. Approximately 85% of identified commissions have reimbursed travel expenses for members. The statute establishing the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom, for example, reads in part as follows:

(i) Funding.—Members of the Commission shall be allowed travel expenses, including per diem in lieu of subsistence, at rates authorized for employees under subchapter I of chapter 57 of title 5, United States Code, while away from their homes or regular places of business in the performance of services for the Commission.34

Compensation

A smaller number of commissions (approximately 33% of those identified) have compensated their members. Among these commissions, the level of compensation is almost always specified, and is typically set in accordance with one of the federal pay scales, prorated to the number of days of service. The most common level of compensation is the daily equivalent of Level IV of the Executive Schedule, which has a basic annual rate of pay of $164,200 in 2018.35 Additionally, these statutes commonly add that any government employee serving on the commission shall not be entitled to additional compensation for their commission service (but may still receive reimbursement for travel expenses). The statute establishing the Antitrust Modernization Commission, for example, provided for member compensation (limited to Level IV of the Executive Schedule), included provisions related to federal officials serving on the panel, and provided for the reimbursement of travel expenses:

(a) Pay.—

(1) Nongovernment employees.—Each member of the Commission who is not otherwise employed by a government shall be entitled to receive the daily equivalent of the annual rate of basic pay payable for level IV of the Executive Schedule under section 5315 of title 5 United States Code, as in effect from time to time, for each day (including travel time) during which such member is engaged in the actual performance of duties of the Commission.

(2) Government employees.—A member of the Commission who is an officer or employee of a government shall serve without additional pay (or benefits in the nature of compensation) for service as a member of the Commission.

(b) Travel Expenses.—Members of the Commission shall receive travel expenses, including per diem in lieu of subsistence, in accordance with subchapter I of chapter 57 of title 5, United States Code.36

Whether commission members are compensated can have consequences for the makeup of the commission. Arguably, compensation may help entice qualified commission members to serve who would otherwise not be willing to do so. Similarly, reimbursement for travel and other expenses may help attract commission members to serve, particularly those whose commission service would require travel. On the other hand, compensation of commission members is likely to increase the overall cost of the commission, particularly among commissions designed to last for a long period of time.

Duties

Commissions are usually statutorily directed to carry out specific tasks. These may include any combination of studying a problem, fact-finding, assessing conditions, holding hearings, conducting an investigation, reviewing policy proposals, making feasibility determinations, crafting recommendations, issuing reports, or other tasks.

The duties statutorily assigned to a commission can range from brief and general to lengthy and detailed. Some statutes include a relatively brief list of duties, while others may spell out in detail the items a commission is tasked to research, investigate, or report upon. For example, the Antitrust Modernization Commission statute included a brief section on four major duties assigned to the commission:

The duties of the Commission are—

(1) To examine whether the need exists to modernize the antitrust laws and to identify and study related issues;

(2) To solicit views of all parties concerned with the operation of the antitrust laws;

(3) To evaluate the advisability of proposals and current arrangements with respect to any issues so identified; and

(4) To prepare and submit to Congress and the President a report in accordance with section 11058.37

By contrast, the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission was provided an extensive list of instructions for material to be assessed by the commission, including direction to investigate and report upon the role played by 22 specific factors in the then-recent economic downtown.38

Hearings

While most commissions are statutorily granted the power to hold hearings as needed in order to acquire information or accomplish other duties of the commission, some commissions are also explicitly instructed to hold hearings as a key duty of the commission. Some commissions have been instructed to hold hearings in specific locations or receive testimony from particular witnesses. The National Commission on Crime Control and Prevention, for instance, was directed to

[convene] field hearings in various regions of the country to receive testimony from a cross section of criminal justice professionals, business leaders, elected officials, medical doctors, and other persons who wish to participate.39

Reports

Commission statutes commonly identify one or more reports that the commission is required to produce, outlining their activities, findings, and/or legislative recommendations. In most cases, a single report is required; in other cases, commissions are required to make one or more interim reports before the final report is issued. Commissions may be directed to submit these reports to Congress, the President, or an executive agency.

Final Reports

Most congressional commissions are required to issue a final report. For example, the National Commission on the Structure of the Air Force was directed to issue a single final report:

Not later than February 1, 2014, the Commission shall report to the President and the congressional defense committees a report which shall contain a detailed statement of the conclusions of the Commission as a result of the study required by subsection (a), together with its recommendations for such legislation and administrative actions it may consider appropriate in light of the results of the study.40

If a commission is required to make policy recommendations, Congress may direct that the final report contain legislative language to implement any recommendations. The statute creating the Commission to Study the Potential Creation of a National Women's History Museum, for example, was required to submit draft legislation for Congress' consideration:

(3) Legislation to carry out plan of action.—Based on the recommendations contained in the report submitted under subparagraphs (A) and (B) of paragraph (1), the Commission shall submit for consideration to the Committees on Transportation and Infrastructure, House Administration, Natural Resources, and Appropriations of the House of Representatives and the Committees on Rules and Administration, Energy and Natural Resources, and Appropriations of the Senate recommendations for a legislative plan of action to establish and construct the Museum.41

In addition to directing a commission to produce legislative language to implement its recommendations, a small number of statutes have also provided for expedited, or "fast track" legislative procedures to govern the consideration of commission recommendations. Defense Base Closure and Realignment Commissions (BRAC) are among the most prominent examples of independent commissions whose recommendations have received "fast track" authority.42

In some instances, the statute may additionally specify that views of members not necessarily agreed upon by the full commission be included in the final report upon an individual member's request. This is usually accomplished by adding that the final report "shall include any minority views or opinions not reflected in the majority report."43

Interim Reports

Legislation requiring commissions to issue interim reports may call for one or more of such reports. These reporting requirements may be designed to provide updates on the progress of a study, to share preliminary findings, to ensure federal agencies comply with the commission's requests, and/or provide Congress with information about the commission's expenses.

The Commission on Wartime Contracting in Iraq and Afghanistan, for example, was instructed to "submit to Congress an interim report on the study… including the results and findings of the study as of [March 1, 2009]."44 Other commissions have been instructed to issue interim reports on a regular basis prior to issuing a final report, or to provide other interim reports as deemed necessary by the commission. P.L. 114-198, establishing the Creating Options for Veterans' Expedited Recovery Commission, directed the commission to submit interim reports both on a regular schedule and on an as-needed basis:

(1) Interim Reports.—

(A) In General.—Not later than 60 days after the date on which the Commission first meets, and each 30-day period thereafter ending on the date on which the Commission submits the final report under paragraph (2), the Commission shall submit to the Committees on Veterans' Affairs of the House of Representatives and the Senate and the President a report detailing the level of cooperation the Secretary of Veterans Affairs (and the heads of other departments or agencies of the Federal Government) has provided to the Commission.

(B) Other Reports.—In carrying out its duties, at times that the Commission determines appropriate, the Commission shall submit to the Committee on Veterans' Affairs of the House of Representatives and the Senate and any other appropriate entities an interim report with respect to the findings identified by the Commission.45

Report Submission

The majority of commissions (approximately 57% of those identified) have been instructed to submit their work product to both Congress and the President. The remainder have typically been submitted to some combination of Congress, the President, and/or an executive branch official and executive agency. In some cases, the statute creating the commission did not specify to whom the report must be submitted.

Statutes that instruct commissions to submit their reports to Congress may require that the report be transmitted to Congress generally,46 to relevant committees, or to individuals, such as chamber or committee leaders. In some cases, these statutes also mandate that the final report shall be made publicly available by the commission. For example, the act creating the Commission on the Roles and Capabilities of the United States Intelligence Community directed the commission to make an unclassified version of its final report publicly available, with classified material made separately available to the President and the intelligence committees of both chambers:

[T]he Commission shall submit to the President and to congressional intelligence committees a report setting forth the activities, findings, and recommendations of the Commission, including any recommendations for the enactment of legislation that the Commission considers advisable. To the extent feasible, such report shall be unclassified and made available to the public. Such report shall be supplemented as necessary by a classified report or annex, which shall be provided separately to the President and the congressional intelligence committees.47

Powers

Commissions are generally provided with authority to perform certain actions that help carry out their mission. Some of these powers, such as holding hearings, or obtaining administrative support from the General Services Administration (GSA) or another federal agency, are commonly granted to all types of commissions. The decision to grant other types of powers likely depends on the goal of the commission in question. For example, a commission established to commemorate an individual or event may require the explicit authority to receive gifts or other commemorative items in order to carry out its mission, while a commission designed to perform an investigation may not.48 By contrast, authority to obtain data from federal agencies may be of particular importance for a commission designed to investigate an event or issue, but less so for a commemorative commission.

Holding Hearings

Commissions commonly hear testimony from outside experts or government officials in the course of conducting a study, developing recommendations, or carrying out an investigation. Accordingly, most commissions are statutorily authorized to hold hearings as needed. For example, the statute creating the Commission on Care states that

[t]he Commission may hold such hearings, sit and act at such times and places, take such testimony, and receive such evidence as the Commission considers advisable to carry out this section.49

The general authority for a commission to hold hearings, as in the example above, is distinct from a specific instruction to hold hearings. Nearly all commissions are given the authority to hold hearings as needed. A smaller number receive additional instruction to hold hearings in specific locations, or receive testimony from particular witnesses.

In some cases, Congress may require that a commission's hearings must be open to the public.50 The statute creating the National Prison Rape Reduction Commission stated the following:

(g) HEARINGS.

(1) In General.—The Commission shall hold public hearings. The Commission may hold such hearings, sit and act at such times and places, take such testimony, and receive such evidence as the Commission considers advisable to carry out its duties under this section.51

Obtaining Information from Government Agencies

Frequently, commissions are tasked with studying a public policy issue or conducting an investigation that requires information or data held by federal agencies. To these ends, commissions are commonly authorized by statute to obtain information from government agencies that may be necessary to carry out the commission's goals. For instance, the Commission on Care was authorized to

secure directly from any Federal agency such information as the Commission considers necessary to carry out this section. Upon request of the Chairperson of the Commission, the head of such agency shall furnish such information to the Commission.52

Although this authority may require government entities to cooperate with the commission, an enforcement mechanism is not typically specified. Absent an enforcement mechanism, such as subpoena authority, the commission might not have recourse against a government entity that did not comply with its requests. This structure—giving the commission authority to secure information but not a mechanism to legally enforce that authority—is commonplace among past congressional commissions.

In at least one instance, a commission was required to notify a standing committee of jurisdiction in either the House or Senate of any difficulty in obtaining information from government agencies. The Commission on Wartime Contracting in Iraq and Afghanistan was provided the following instruction:

(2) Inability to obtain documents or testimony.—In the event the Commission is unable to obtain testimony or documents needed to conduct its work, the Commission shall notify the committees of Congress of jurisdiction and appropriate investigative authorities.53

Subpoena Authority

On occasion, Congress has granted the authority to issue subpoenas to congressional commissions. Subpoena authority is relatively rare; nine congressional commissions created since the 101st Congress have been identified as having subpoena authority. These commissions are listed in Table 2.

|

Commission Name |

Authority |

Date of Enactment |

|

Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission |

P.L. 111-21; 123 Stat. 1628 |

May 20, 2009 |

|

Human Space Flight Independent Investigation Commission |

P.L. 109-155; 119 Stat. 2943 |

December 30, 2005 |

|

National Prison Rape Reduction Commission |

P.L. 108-79; 117 Stat. 985 |

September 4, 2003 |

|

National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States |

P.L. 107-306; 116 Stat. 2410 |

November 27, 2002 |

|

National Commission for the Review of the Research and Development Programs of the United States Intelligence Community |

P.L. 107-306; 116 Stat. 2440 |

November 27, 2002 |

|

National Commission for the Review of the National Reconnaissance Office |

P.L. 106-120; 113 Stat. 1622 |

December 3, 1999 |

|

National Gambling Impact Study Commission |

P.L. 104-169; 110 Stat. 1485 |

October 3, 1996 |

|

Commission on Protecting and Reducing Government Secrecy |

P.L. 103-236; 108 Stat. 527 |

April 30, 1994 |

|

National Commission on Financial Institution Reform, Recovery, and Enforcement |

P.L. 101-647; 104 Stat. 4890 |

November 29, 1990 |

Source: CRS analysis of Congress.gov database query, 101st Congress to 115th Congress.

The perceived reluctance of many policymakers to give subpoena authority to congressional commissions may stem from concerns about the misuse of the authority; private citizens are not subject to the check of periodic elections the way that Members of Congress are, and thus may have fewer incentives to use subpoena authority in an appropriate manner. The National Gambling Impact Study Commission, for example, was authorized to subpoena documents, but not to compel the testimony of witnesses;54 supporters of the legislation noted that providing for limited subpoena authority in this manner "should satisfy those who are concerned that the commission might misuse its subpoena authority to create some sort of public spectacle,"55 and "will allow the Commission to conduct its study while, at the same time, it allays the fears of those who thought the subpoena power would be overly intrusive."56

Alternatively, legislators may be concerned that subpoenas may be used by the commission for political purposes. Supporters of the proposed legislation creating the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission, for instance, emphasized that by requiring the concurrence of at least one minority-appointed member to issue a subpoena, the legislation would "[provide] additional assurance that the examination undertaken by the commission, and in its exercise of subpoena authority, will not be politicized."57

On the other hand, if it is judged that a commission is likely to need information, documents, or testimony from agencies, firms, or individuals who may not be cooperative, subpoena authority may be a valuable tool.

Other Powers

Past commissions have frequently been granted other powers intended to facilitate their day-to-day operations. Many of these are intended to ease the logistical burden of finding meeting or office space, procuring equipment, or obtaining other necessary services. Some of the most common provisions permit commissions to

- use the U.S. mail system in the same manner as federal agencies;

- enter into contracts;

- obtain services from outside experts and consultants;

- request the detail of federal employees to the commission;

- obtain administrative support (such as assistance with human resources, obtaining office and meeting space, and procuring equipment) from the General Services Administration or another federal agency; and

- accept gifts, donations, and/or volunteer services.58

The Virgin Islands of the United States Centennial Commission, for example, was granted some version of each of the aforementioned authorities, using statutory language common to commission statutes:

(c) Detail of Federal Employees.—Upon request of the Commission, the Secretary of the Interior or the Archivist of the United States may detail, on a reimbursable basis, any of the personnel of the Department of the Interior or the National Archives and Records Administration, respectively to the Commission to assist the Commission to perform the duties of the Commission.

(d) Experts and Consultants.—The Commission may procure such temporary and intermittent services from experts and consultants as are necessary to enable the Commission to perform the duties of the Commission.

…

(b) Mails.—The Commission may use the United States mails in the same manner and under the same conditions as other Federal agencies.

…

(d) Gifts, Bequests, Devises.—The Commission may solicit, accept, use, and dispose of gifts, bequests, or devises of money, services, or property, both real and personal, for the purpose of aiding or facilitating the work of the Commission.

(e) Available Space.—Upon request of the Commission, the Administrator of General Services shall make available to the Commission, at a normal rental rate for Federal agencies, such assistance and facilities as may be necessary for the Commission to perform the duties of the Commission.

(f) Contract Authority.—The Commission may enter into contracts with and compensate the Federal Government, State and local government, private entities, or individuals to enable the Commission to perform the duties of the Commission.59

While statutes creating commissions typically grant the authority for a commission to request administrative support services from the GSA, the GSA need not be the source of administrative support for the commission. Some commissions may employ the services of Washington Headquarters Services, an organization within the Department of Defense that provides administrative and other services.60 Other commissions may be provided with multiple options for administrative assistance; for example, the statute creating the Commission on Servicemembers and Veterans Transition Assistance provided the following:

The Secretary of Defense, the Secretary of Veterans Affairs, and the Secretary of Labor shall, upon the request of the chairman of the Commission, furnish the Commission, on a reimbursable basis, any administrative and support services as the Commission may require.61

Rules and Procedures

In general, most statutes establishing commissions do not outline a detailed set of rules and procedures that the commission must follow when conducting its business. However, the statutory language often provides a general structure, including a mechanism for selecting a chair, specifying the size of a quorum, and procedures for creating rules.

Selection of Chairperson

Commission statutes generally provide for either a single chairperson, or multiple co-chairpersons, and commonly specify the method by which the chairperson(s) shall be selected. The most common arrangement found among commissions is for the chairperson or co-chairpersons to be elected by a vote of the commission. The statute creating the Western Hemisphere Drug Policy Commission, for instance, directed that "[a]t the initial meeting, the Commission shall select a Chairperson from among its members."62

When a chairperson is not elected by the commission, the next most frequent arrangement is for the appointment of the chairperson(s) by the President, congressional leaders, or an executive branch official. In many cases, appointment authority is provided to a single individual; for example, the President appointed the chairperson of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States.63 In contrast, the act creating the Commission on the Abraham Lincoln Study Abroad Fellowship Program jointly provided appointment authority to the Senate majority and minority leaders, and the House Speaker and minority leader.64

In a smaller number of cases, chairpersons have been officials designated by statute. The Secretary of Health and Human Services, for example, was directed to serve as the chairperson of the Commission on Indian and Native Alaskan Health Care.65

Arrangements that provide for singular chairpersons may improve the efficiency of the commission, particularly if partisan or ideological divisions become an issue in organizational decisionmaking. On the other hand, co-chair arrangements may lend partisan or ideological balance to the activities of the commission, and allow for "buy-in" from a greater range of stakeholders.

Quorum Requirements

Most statutes establishing commissions (approximately two-thirds) provide that a quorum will consist of a particular number of commissioners. In the majority of cases, a quorum is set at a majority of members, though a small number of statutes have established quorum thresholds of less than a majority of members,66 and others a supermajority of members.67 In some cases, statutes have permitted commissions to conduct hearings and receive testimony if less than a quorum is present.68

Supermajority Requirements

Most statutes establishing commissions are silent on the threshold for passage of a final report, agreeing to particular recommendations, or other actions taken by a commission. In such cases, it is commonly assumed that the default threshold for passage is a simple majority. Some statutes state explicitly that the commission's final report shall contain only those recommendations agreed to by a majority of its members.69

However, Congress has in a smaller number of cases specified that the vote of greater than a majority of the commission is necessary to agree to take particular actions. For example, the National Bipartisan Commission on the Future of Medicare's statute required that the commission's report include only "those recommendations, findings, and conclusions of the Commission that receive the approval of at least 11" of its 17 commissioners—a threshold of approximately two-thirds.70

Establishment of supermajority thresholds may guarantee that the views of a minority of the commission are heard and incorporated, thereby helping to ensure a final report that is more widely supported than would otherwise be the case. This may improve the commission's standing in the eyes of legislators and the public, ensure some degree of bipartisan support for the final work product, and result in a set of recommendations with a wider base of support in Congress.

On the other hand, the lack of a supermajority requirement does not preclude the achievement of a bipartisan or nonpartisan work product from the commission. It is not uncommon for a congressional commission to deliver a final product that is unanimously agreed to by all members in the absence of rules requiring that outcome. For example, the final reports of both the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States (the 9/11 Commission) and the Commission on the Prevention of Weapons of Mass Destruction were unanimously agreed to by all members.71

In addition, supermajority requirements cannot fully guarantee widespread agreement among commissioners. If the policy issue being addressed by the commission is particularly partisan or ideological in nature, a commission may simply reflect such divisions rather than overcome them; this may ultimately lead to a report where commissioners are unable to agree on recommendations to address the most critical topics. Alternatively, the commission may produce final work products with fewer specific, concrete findings or recommendations, and more general statements that are less likely to generate wide dissent.

Formulating Other Rules of Procedure

In general, commission statutes have not prescribed many rules of operation. Many commission statutes are silent on internal commission procedure. Some have explicitly granted the right of the commission to establish its own rules. The National Gambling Impact Study Commission, for example, was authorized to "establish by majority vote any other rules for the conduct of the Commission's business, if such rules are not inconsistent with this Act or other applicable law."72

This formulation may result in commission members drafting and adopting a set of formally written rules, adopting rules on a more informal or as-needed basis, or simply operating without formal rules and relying on members' collegiality as the basis for proceedings. Whether the commission ultimately adopts a set of formal, written rules or instead relies on informal norms to guide its operation may be determined by a variety of factors, including the size of the commission, frequency of meetings, member preferences regarding formality, the level of collegiality among members, and the amount of procedural guidance provided by the commission's authorizing statute.

Staff

Congressional commissions are usually authorized to hire a staff. Most statutes specify that the commission shall hire a lead staffer, often referred to as a "staff director," "executive director," or another similar title, in addition to further staff as needed. Rather than mandate a specific staff size, many commissions are instead authorized to appoint a staff director and other personnel as necessary, subject to the limitations of available funds.

Most of these congressional commissions are also authorized to hire consultants, procure intermittent services, and to request that federal agencies detail personnel to aid the work of the commission.

Hiring, Compensation, and Benefits of Commission Staff

Commissions are typically provided the authority to make hiring decisions and set staff salaries. In some cases, a statute may designate the individual or individuals on the commission responsible for hiring staff and setting staff compensation. Statutes commonly provide this authority to the entire commission,73 to the chairperson or co-chairpersons (either solely, or upon the approval of the rest of the commission),74 or to the lead staffer (often upon the approval of the commission).75

In most cases, the authority to determine staff compensation is left to the commission, the chairperson(s), or to the lead staffer. However, commission statutes frequently establish a maximum rate of pay for commission staff, typically a particular level of the Executive Schedule or General Schedule. In cases where staff compensation limits are specified, Level V of the Executive Schedule is the most common limit chosen for commissions.76 In 2018, positions at level V of the Executive Schedule carried annual pay rates of $153,800.77

In order to facilitate the process of filling staff positions, most commissions are authorized to make staff hires without regard to certain laws that govern pay rates and the competitive service. The National Commission for the Review of the Research and Development Programs of the United States Intelligence Community, for example, was authorized to hire a staff director and other personnel without regard to particular sections of the U.S. Code, but with a specified limit on the rate of pay:

The co-chairs of the Commission, in accordance with rules agreed upon by the Commission, shall appoint and fix the compensation of a staff director and such other personnel as may be necessary to enable the Commission to carry out its duties, without regard to the provisions of title 5, United States Code, governing appointments in the competitive service, and without regard to the provisions of chapter 51 and subchapter III of chapter 53 of such title relating to classification and General Schedule pay rates, except that no rate of pay fixed under this subsection may exceed the equivalent of that payable to a person occupying a position at level V of the Executive Schedule under section 5316 of such title.78

Some (but not all) statutes additionally provide that commission staff shall be considered federal employees for the purpose of benefits. The statute creating the Presidential Advisory Commission on Holocaust Assets in the United States, for example, stated the following:

(5) Employee benefits.—

(A) In General.—An employee of the Commission shall be an employee for the purposes of chapters 83, 84, 85, 87, and 89 of title 5, Untied States Code, and service as an employee of the Commission shall be service for purpose of such chapters.

(B) Nonapplication to members.—This paragraph shall not apply to a member of the Commission.79

Decisions related to staff size and compensation will likely have a significant effect on the overall cost of the commission. Reducing staff compensation or size may arguably result in considerable cost savings. On the other hand, reducing staff compensation may make it more difficult to hire qualified staff; additionally, limiting staff size could negatively affect the ability of a commission to function efficiently, resulting in a lower-quality work product or increasing the amount of time needed for the commission to complete its mission.

Other Staff

In addition to hiring staff, many commissions are granted the authority to obtain services from detailees, consultants, and volunteers.

Detailees

Most commissions are authorized to request detailees from any federal agency to assist the commission. In almost all cases, the statute also specifies that any individual detailee "shall retain the rights, status, and privileges of his or her regular employment without interruption."80

Some statutes creating commissions provide the authority to request detailees, but place limits on which federal employees may be detailed to a commission. The Virgin Islands of the United States Centennial Commission, for instance, was provided authority to request detailees from only the Department of the Interior and the National Archives and Records Administration.81 The statute creating the Human Space Flight Independent Investigation Commission specifically exempted NASA employees from commission detail.82

Statutes granting detailee authority also generally specify whether or not an agency will be reimbursed by the commission for the cost of the detail. Providing for detailees on a reimbursable basis may make agencies more willing to comply with a commission's detail requests, but may also increase the overall cost of the commission.

Experts and Consultants

In addition to detailees, commissions are frequently granted authority to procure services from experts and consultants in accordance with specific laws, and subject to certain limitations on pay. As with commission staff, the pay of experts and consultants is often limited to a particular level of either the Executive Schedule or General Schedule. Employing language commonly found in commission statutes, the statute creating the Guam War Claims Review Commission provided for the procurement of experts and consultants whose compensation would be capped at a level of the General Schedule:

(c) Experts and Consultants.—The Commission may procure temporary and intermittent services under section 3109(b) of title 5, United States Code, but at rates for individuals not to exceed the daily equivalent of the maximum annual rate of basic pay for GS-15 of the General Schedule. The services of an expert or consultant may be procured without compensation if the expert or consultant agrees to such an arrangement, in writing, in advance.83

Volunteer Services

Some commissions are provided the authority to accept volunteer and uncompensated services. Relatively few commissions identified since the 101st Congress (about 12%) have been provided this authority; however, it is somewhat more common among commemorative commissions (about 44% of commemorative commissions were provided this authority) than either policy or investigative commissions. The statute creating the John F. Kennedy Centennial Commission, for instance, reads as follows:

Volunteer and Uncompensated Services.—Notwithstanding section 1342 of title 31, United States Code, the Commission may accept and use voluntary and uncompensated services as the Commission determines necessary.84

Costs and Funding

Aggregate costs of congressional commissions vary widely, ranging from several hundred thousand dollars to over $10 million. Expenses for any individual commission are difficult to predict and depend on a variety of factors, the most important of which are the number of paid staff and the duration of the commission. Some commissions have few or no full-time staff; others, such as the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States (the 9/11 Commission), employ a large staff. The 9/11 Commission received more than $10 million in appropriations and employed a full-time staff of 80.85

Secondary factors contributing to commission expenses include the number of commissioners, how often the commission meets or holds hearings, and the number and size of publications produced by the commission. Although commissions are primarily funded through congressional appropriations, many commissions are statutorily authorized to accept donations of money and volunteer labor, which may offset costs.

Authorization of Funds

Congress may choose to authorize the appropriation of funds for the operations of a commission. Commission statutes that authorize funding often choose a dollar amount, without additional specific qualifications. The statute creating the Guam War Claims Review Commission,86 for example, simply states, "There is authorized to be appropriated $500,000 to carry out this act." Other commission statutes provide for authorizations that correspond to fiscal years, or otherwise limit how long funding may be available to the commission. The Commission to Study the Potential Creation of a National Museum of the American Latino received the following authorization:

There are authorized to be appropriated for carrying out the activities of the Commission $2,100,000 for the first fiscal year beginning after the date of enactment of this Act and $1,100,000 for the second fiscal year beginning after the date of enactment of this Act.87

In other cases, statutes may authorize the appropriation of "such sums as necessary" for the expenses of a commission rather than a specific dollar amount.88

A smaller number of commissions—usually commissions designed to commemorate an event or individual—have been explicitly prohibited from receiving federal funds. In lieu of federal funding, these commissions are typically authorized to accept donations, gifts, and/or volunteer efforts. Section 10 of the statute creating the John F. Kennedy Centennial Commission simply reads, "No Federal funds may be obligated to carry out this Act."89 Along similar lines, P.L. 112-272, which established the World War I Centennial Commission, stated that

[g]ifts, bequests, and devises of services or property, both real and personal, received by the Centennial Commission under section 6(g) shall be the only source of funds to cover the costs incurred by the Centennial Commission under this section.90

Sources of Funding

Some commissions are funded directly by specific appropriations. For example, the Helping to Enhance the Livelihood of People Around the Globe Commission—for which the enacting statute authorized the appropriation of "such sums as necessary"91—was funded through specific line items in FY200492 and FY200593 appropriations acts.

Other commissions are instead funded by an agency appropriation or through another mechanism. For example, the statute creating the Commission on the Implementation of the New Strategic Posture of the United States, directed that funding for the commission be "provided from amounts appropriated for the Department of Defense."94 The statute creating the Motor Fuel Tax Enforcement Advisory Commission provided that "[s]uch sums as are necessary shall be available from the Highway Trust Fund for the expenses of the Commission."95

FACA Applicability

The Federal Advisory Committee Act (FACA) mandates certain structural and operational requirements, including formal reporting, administration, and oversight procedures, for certain federal advisory bodies that advise the executive branch.96

Whether FACA requirements apply to a particular advisory commission may depend on a number of factors, including whether most appointments to the commission are made by members of the legislative or the executive branch, and to which branch of government the commission must issue its report, findings, or recommendations.

Often, a statute will direct whether FACA shall apply to a given commission. The act creating the Commission on the Prevention of Weapons of Mass Destruction Proliferation and Terrorism (P.L. 110-53) simply stated, "The Federal Advisory Committee Act (5 U.S.C. App.) shall not apply to the Commission."97 Some commission statutes exempt a commission from FACA, but still mandate FACA-like requirements, such as holding public hearings or making available a public version of the final report.98