Introduction

Congress is again debating work requirements for programs providing need-tested assistance to low-income families and individuals. Need-tested programs provide benefits and services to individuals and families based on financial need (usually low income). This is in contrast to social insurance programs such as Social Security and Unemployment Insurance, which base their benefits on past work.

Work requirements for cash assistance for parents in needy families with children receiving public benefits have been part of policy debates since the 1960s. Those debates culminated in the 1996 welfare reform law (P.L. 104-193), which created the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) block grant to replace the pre-1996 cash assistance program of Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC). Since the enactment of the 1996 law, extending work requirements to other need-tested programs has sometimes been raised in policy debates about need-tested programs. Legislation before the 115th Congress—the House-passed version of H.R. 2—would expand work requirements in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). H.R. 5861, reported to the House from the Ways and Means Committee, would alter some of TANF's rules regarding work. In addition, the Trump Administration is currently granting demonstration waivers for states to implement work requirements for certain recipients of Medicaid, and has proposed expanded work requirements for housing assistance programs.

Work requirements for recipients of government assistance seek to achieve a variety of policy goals. They can attempt to offset work disincentives in government assistance programs and promote a culture of work over dependency on government benefits. Work requirements can also reduce the assistance caseloads, leading to government savings. They can screen out those who decide that the benefit of receiving assistance is not worth the cost of complying with a work requirement. They can also be used to remove from the assistance programs those who do not comply with the societal norm of work.1 In general, the economic status of most individuals is tied to work—either current work, past work, or the work of another family member.2 Thus, requiring work can be seen as a means of improving the economic status of individuals and families, as it is the primary means of lifting them out of poverty.

What does the research evidence indicate about the impact of work requirements in meeting these policy goals? Most of the research that addresses this issue comes from a set of experiments, conducted prior to the 1996 welfare reform, on alternative approaches to the work and education provisions in TANF's predecessor program, AFDC. This report summarizes the findings from the pre-1996 welfare-to-work experiments as well as the limits of applying those findings to the current policy debate around work requirements.

The Pre-1996 Welfare-to-Work Experiments

Before the enactment of the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996 (PRWORA, P.L. 104-193), a large number of experiments were fielded to inform the welfare reform debates that spanned four decades, from the 1960s to the mid-1990s.3 The experiments were demonstrations of alternative policies and were evaluated using the randomized controlled trial (RCT) method, which is used to isolate the effect of differing policies from other factors that can influence outcomes.

|

Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs) An assessment of a welfare-to-work program usually focuses on outcomes, such as the rate at which individuals find work, their earnings, whether they leave assistance rolls, and whether they save the federal and state governments money through reduced assistance payments. While observing these outcomes conveys important information, it does not directly measure the impact of a policy—the difference the program makes—in recipients achieving the outcomes. Many factors affect employment, earnings, and benefit receipt of individuals beside the effectiveness of a welfare-to-work requirement and an employment and education program. Recipients are likely to eventually find employment on their own, even without a program. The context in which a program operates—the health of the national and local economy; the occupational structure of the area studied; and the characteristics of the caseload, such as age, educational attainment, and past work experience—can affect the rate at which recipients find work and their wages. Program rules other than the work requirement also affect whether recipients who find work leave the program. The evaluations discussed in this section of this report were conducted using the randomized control trial (RCT) method, which is used to isolate the impact of different policies on outcomes. RCTs randomly assigned AFDC recipients in a site to treatment groups (those subject to requirements and provided services) and a control group (those not subject to requirements and services). If a sufficiently large number of people is randomly assigned to two or more groups, statistical theory holds that the characteristics of the people in these groups will be identical. Additionally, the random assignment to groups in the same place at the same time ensures that all groups are exposed to the same context in terms of economic conditions. There are several potential limitations for applying the results of RCTs to understanding the impact of work requirements on recipients of need-tested assistance. One limitation is that the RCTs studied the population already receiving assistance: they did not measure the impact that a work requirement might have in the rate at which individuals come onto the assistance rolls. A second potential limitation is that a study's findings might hold for a given time, place, population, and context, but may not be generalizable beyond that. (This limitation is not limited to studies that use the RCT method.) This was less of a concern in the past when looking at programs related to AFDC because the main findings discussed in this section were replicated in many different locations. However, it is a potential limitation when looking at different populations, such as those in SNAP, Medicaid, and housing assistance programs. That these studies were generally conducted in the early 1990s raises the question of whether they are generalizable today, even to the TANF population, given that the economic and program context has changed over the past two decades. |

The era of experimentation on alternative welfare policies began with the negative income tax (NIT) experiments initiated in the 1960s and 1970s. They were conducted because the welfare reforms offered (but never enacted) by Presidents Nixon and Carter were based on the NIT model, which was an income guarantee and a gradual "taxing back" of benefits as incomes increased.4 In the 1980s, the focus of the experimental research shifted to examining programs that required work and/or provided employment services with the goal of moving recipients from nonwork on the AFDC assistance rolls to work and being off the rolls.5 This research culminated in evaluations fielded in the early 1990s in the federally sponsored National Evaluation of Welfare to Work Strategies (NEWWS) study; evaluations required of states that obtained "waivers" of AFDC requirements related to work; and the Minnesota Family Investment Program (MFIP), which required special legislative authorization.

Mandatory Welfare-to-Work Programs

This report focuses on findings from mandatory welfare-to-work programs. These programs combined work requirements with a program that provided funded employment and educational services. Recipients were assigned to activities such as job search or required to enroll and make progress in educational activities, and they were sanctioned if they did not participate as required. Some of these programs included independent job search—requiring recipients to look for employment on their own—but also included other activities if that independent job search did not result in employment. The sanction for not participating in required activities in most of the evaluated programs was a reduction—not a termination—of a family's benefit.

The evaluations of the pre-1996 welfare-to-work experiments, taken as a combined body of research, provided a fairly consistent set of findings. This report uses findings from NEWWS to illustrate the impact of mandatory welfare-to-work programs. The NEWWS findings were consistent with a large number of evaluations—fielded at different times in different sites—from the 1980s through the mid-1990s.6 In addition, this report examines a second set of evaluations of mandatory welfare-to-work programs that also provided "earnings supplements," which continued benefits for those who found work while on the rolls.

The studies discussed here were initiated before 1996. However, many of the evaluations were not published until well after the enactment of the 1996 welfare reform law. The law permitted welfare-to-work experiments that were initiated prior to its enactment to continue after enactment, up to the date of the experiment's scheduled expiration.

Impact of Programs on Employment, Earnings, and Assistance Receipt

Mandatory welfare-to-work programs often increased rates of employment and average earnings above what was observed in the absence of such programs. The positive impact on employment and earnings was usually modest in size. Some evaluations found that the employment and earnings impacts faded with time, so that the main effect of such programs was to accelerate entry into the workforce.

Mandatory welfare-to-work programs often resulted in lower rates of receipt of assistance (usually measured for both cash and food assistance) and lower assistance payments, on average. Additionally, while employment and earnings impacts sometimes faded over time, the reductions in assistance payments tended to persist as a long-term impact. Lower levels of assistance payments stemmed from both fewer recipients on the rolls and lower benefit payments as recipients worked and had earned income (though, under AFDC rules, the time period over which a recipient could have substantial earnings and remain on the rolls was limited). Additionally, some of the reduced assistance payments resulted from sanctions on families that did not comply with the participation requirement.

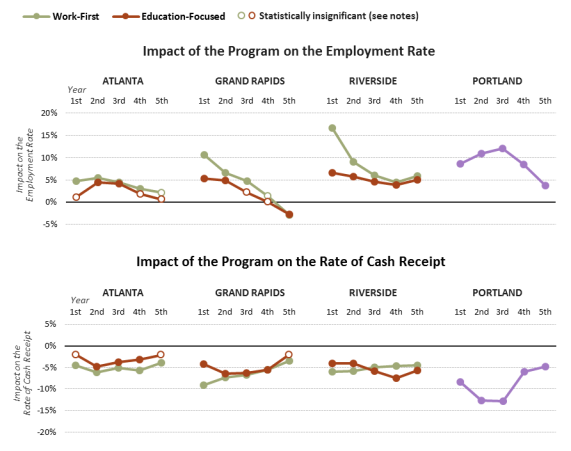

The NEWWS evaluation was designed to provide evidence on whether a "work-first" approach or an "education-focused" approach yielded larger impacts.7 The work-first approach generally assigned recipients to job search as their first activity. At three NEWWS sites discussed here (Atlanta; Grand Rapids, MI; Riverside, CA), job search was conducted in the context of a "job club," which included classroom instruction as well as structured and supervised contacts with employers. The education-focused approach assigned those without a high school diploma to basic education activities first, and those with high school diplomas to vocational education or other skills-building activities. NEWWS tested both approaches head-to-head in the same location, at the same time, and with the same population.

The basic finding from NEWWS is that both approaches increased employment and reduced assistance payments. The impacts from the work-first approach occurred quickly. For example, the Riverside work-first program (the findings shown here were restricted to those without a high school diploma) had the largest immediate impacts, with the employment rate for the treatment group exceeding that of the control group by almost 17 percentage points. The employment impacts for all programs declined over time, as members of the control group became more likely to be employed in later years. The cash assistance impacts also tended to fade—again because members of the control group also left assistance over time. However, many programs—work first or education focused—had lasting impacts on both rates of employment and receipt of cash assistance through year five after random assignment. All lasting impacts of the programs, except for both programs in Grand Rapids, can be considered positive for a welfare-to-work program (higher rates of employment, lower rates of benefit receipt).

A NEWWS program in Portland, OR, operated a "mixed strategy." Case managers in that program had the discretion to offer preparation for a General Educational Development (GED, or high school equivalent) credential to those they believed had a good chance of obtaining it. The program also allowed participants to forgo low-paying jobs to look and wait for higher-paying jobs. Of all the NEWWS programs, Portland's produced some of the largest employment impacts. However, its mixed strategy was not tested head-to-head against a pure work-first or education-focused strategy, so it is not known whether the large impacts resulted from the program's strategy or from the particular economic context of Portland at that time.

Figure 1 shows NEWWS findings on employment and cash assistance receipt impacts for years one through five following random assignment. The figure shows the impacts (the difference the program made) in the employment rate and cash receipt rate for both the work-first and education-focused programs in Atlanta, Grand Rapids, and Riverside, as well as the program in Portland.

Impacts on Income

The welfare-to-work experiments of the late 1980s and early 1990s provided evidence that mandatory welfare-to-work programs by themselves did not increase total income (i.e., the sum of earnings and government assistance). On average, earnings tended to be low; thus, they offset, but did not exceed, the reduction in assistance. Typically, the impact on average incomes was not statistically different from $0. Even the Portland and Riverside NEWWS programs, which had relatively large employment impacts, did not increase incomes on average over the five years.

However, a group of evaluations were conducted on programs that provided "earnings supplements" (i.e., continued benefits to families in cases where the parent found a job and would have become ineligible for AFDC under its regular rules). MFIP had an explicit goal of increasing work, reducing dependence, and reducing poverty. MFIP participants who went to work could continue to receive assistance from the program at higher earnings levels and for longer periods of time than was permitted under AFDC at that time. The MFIP evaluation found that the program increased employment and earnings and increased incomes. However, it did not reduce receipt of assistance.8 Other programs that combined work requirements with earnings supplements—under waivers of AFDC's rules that restricted benefits for families with earnings—were conducted in Connecticut, Florida, Vermont, and Virginia. All of these programs had positive employment impacts. They also increased incomes during some periods after entry into the program; in the case of Connecticut, the time periods when incomes were increased related to the structure of the program (e.g., before the imposition of its 21-month time limit on benefit receipt).9 The statistically significant income impacts for Florida's, Vermont's, and Virginia's programs were less systematic.

However, the studies also illustrated a policy trade-off. MFIP continued aid for working families. The Connecticut program continued aid for working families before the time limit. Both programs increased incomes. MFIP did not reduce assistance payments, and the Connecticut program did not reduce assistance payments before the time limit. Additionally, in both of these evaluations, the income increase had faded by the end of the evaluation, typically when few participants were on the assistance rolls.10

Table 1 summarizes the findings of these evaluations, showing the change in income from earnings, cash assistance, and food benefits. Some evaluations reported these dollar amounts differently (e.g., quarterly rather than annually) and Vermont and Virginia calculated total income as being different from the sum of the changes in earnings, cash, and food benefits.

Table 1. Impacts on Total Income of Selected Welfare-to-Work Programs that Expanded Assistance to Working Families

(Increases in income that are statistically different from $0 are shown in bold, insignificant differences are in italics; year is the year after random assignment)

|

Change in Total Income |

|||||

|

Period Covered |

Change in Earnings |

Change in Cash and Food Assistance Payments |

Dollars |

Percentage |

|

|

MFIP (all single parents, random assignment from 4/1994 to 3/1996 ) |

Quarterly Average, Year 1 |

$25 |

$230 |

$255 |

11.2% |

|

Quarterly Average, Year 4 |

122 |

97 |

219 |

8.2 |

|

|

Quarterly Average, Year 6 |

39 |

34 |

72 |

2.3 |

|

|

Connecticut JOBS First (random assignment from 1/1996 to 12/1997) |

Annual Average, Years 1-2 |

419 |

722 |

1,140 |

11.6 |

|

Annual Average, Years 3-4 |

490 |

-456 |

34 |

0.3 |

|

|

Florida (Escambia County, random assignment from 5/1994 to 10/1996) |

Annual Average, Year 1 |

240 |

-172 |

67 |

1.0 |

|

Annual Average, Year 3 |

910 |

-414 |

496 |

8.1 |

|

|

Annual Average, Year 4 |

567 |

-314 |

253 |

4.0 |

|

|

Vermont (random assignment from 7/1994 to 12/1996)a |

Annual Average, Years 1-2 |

177 |

-110 |

117 |

1.2 |

|

Annual Average, Years 3-4 |

713 |

-373 |

442 |

4.4 |

|

|

Annual Average, Years 5-6 |

634 |

-489 |

206 |

2.0 |

|

|

Virginia (random assignment from 7/1995 to 8/1997)b |

Quarter 1 |

28 |

-25 |

-52 |

-2.4 |

|

Quarter 5 |

110 |

-18 |

176 |

8.3 |

|

|

Quarter 14 |

145 |

-5 |

54 |

1.9 |

|

Source: Congressional Research Service (CRS) summary of findings of final evaluation reports of the selected welfare-to-work experiments. See Lisa A. Gennetian, Cynthia Miller, and Jared Smith, MFIP: Turning Welfare into a Work Support. Six Year Impacts on Parents and Children from the Minnesota Family Investment Program, Manpower Demonstration Research Corporation (MDRC), July 2005; Dan Bloom, Susan Scrivener, and Charles Michalopoulos, et al., Jobs First. Final Report on Connecticut's Welfare Reform Initiative, MDRC, February 2002; Dan Bloom, James J. Kemple, and Pamela Morris, et al., The Family Transition Program: Final Report on Florida's Initial Time-Limited Welfare Program, MDRC, December 2000; Susan Scrivener, Richard Hendra, and Cindy Redcross, WRP. Final Report on Vermont's Welfare Restructuring Project, MDRC, September 2002; and Anne Gordon and Susanne James-Burdumy, Impacts of the Virginia Initiative for Employment Not Welfare, Mathematica Policy Research Inc., January 2002.

a. Total income includes the effect of taxes, so it does not represent the sum of the earnings and assistance change.

b. Total income includes the effect on child support income, so it does not represent the sum of the earnings and cash and food assistance changes.

In addition to the positive employment and income impacts, some of the evaluated programs that provided earnings supplements also improved measured outcomes for children, particularly school achievement. Note that programs that did not supplement earnings—such as NEWWS—had no systematic impacts on outcomes for children.11 Mandatory welfare-to-work programs, whether accompanied by earnings supplements or not, had negative effects on outcomes such as school achievement for adolescents.12

The Impact of TANF Was Not Experimentally Evaluated

After the 1996 welfare reform law, mandatory welfare-to-work programs were no longer considered experiments, they were considered to be the policy. Thus, TANF was never evaluated.13

Differences in TANF from Piloted Programs

TANF differed from the piloted programs evaluated before 1996 in a number of ways that limit the automatic application of the findings from those experiments to TANF. There were differences in program rules, performance measurement, and incentives to reduce the caseload.

Different Program Rules

The pre-1996 program exempted single mothers with children under the age of 3, though a number of the evaluated programs required participation for mothers with children as young as 1 year old. Under TANF, states determine exemptions from the work requirements, including exemptions for mothers with young children. Some states exempt mothers of newborn children for as little as three months, with many others exempting only mothers with children under the age of 1.14

In most evaluated pre-1996 programs, the sanction for not complying with work requirements was a reduction in the family's cash benefit, not termination of the benefit for the whole family. Under TANF, states determine the sanction for a family that does not comply with work requirements, with most states ultimately ending benefits for the whole family.

A Performance System that Emphasizes Monthly Rates of Work or Participation in Activities, Not Impacts or Outcomes

TANF gave states flexibility to design their programs, but it established a performance system to assess them that requires states to meet a minimum work participation rate (WPR), set statutorily at 50% for all families and 90% for two-parent families (though, as discussed below, these percentages are reduced if a state reduces its caseload). States that do not meet their minimum WPR risk a reduction in their federal funding. There are detailed rules for what types of participation count toward meeting the minimum percentages. Employment while being on the benefit rolls counts as participation. The two most common types of participation in welfare-to-work activities are time limited: job search and readiness is limited to 12 weeks in a 12-month period, and vocational educational training is limited to 12 months in a recipient's lifetime. Participation in a General Educational Development (GED) program for recipients without a high school degree does not count in many circumstances. WPR also measures participation based on a minimum number of hours per week for each month on the rolls. The evaluated studies reported on whether the mandatory welfare-to-work programs increased participation in activities over longer periods of time.

The 50% and 90% thresholds were not informed by the findings of the pre-1996 welfare-to-work experiments—that is, they are not based on evidence from these programs. The 50% and 90% requirements implied higher rates of monthly participation than were achieved in the evaluated pre-1996 programs, even those that reported relatively large employment impacts.15

TANF Has Incentives for States to Seek to Reduce the Caseload

The AFDC program provided unlimited matching grants to states to cover a part of the cost of providing assistance to needy families. TANF is a block grant. The fact that the block grant provides states with a set amount of money that does not depend on the number of families who receive assistance provides one incentive to reduce the caseload. States can use the "savings" from caseload reduction for other purposes, and must bear the cost of increased caseloads.

Additionally, the minimum WPR can be either fully or partially met through caseload reduction because states receive credit against the minimum standards (50% or 90%) they must meet when they reduce their caseloads.

Caseload Reduction and Work Participation Under TANF

The two most defining characteristics of cash assistance for needy families in the post-1996 period have been caseload reduction and states technically meeting their minimum WPR, but often in ways other than engaging nonemployed recipients in activities. In FY1995, a monthly average of 4.9 million families received AFDC cash assistance. In FY2017, a monthly average of 1.4 million families received TANF assistance. In the early years of TANF, before FY2000, caseload reduction was accompanied by reductions in child poverty and increases in work among single mothers. However, since 2000 caseloads have generally continued to decline (except for a brief increase associated with the 2007 to 2009 recession), even in periods when child poverty and the number of families who met TANF financial eligibility rules increased.16

Under TANF, most states have met their minimum WPR standards through either caseload reduction or assisting families with earnings. In FY2016, less than one-fourth of nonemployed adult recipients were reported by states as engaged in welfare-to-work activities, a proportion that is similar to most years of TANF (over the FY2002-FY2016 period, the highest percentage of nonemployed individuals reported as engaged in activities was 27%).17

The results of the pre-1996 welfare-to-work experiments should not be confused with the impact of TANF. The experience of TANF after 1996 illustrates how policies that were evaluated in piloted experiments could differ from those actually implemented in an ongoing program. TANF itself has not been evaluated using methods similar to those used in the pre-1996 experiments.

Work Requirements for SNAP, Medicaid, and Housing Assistance

Much of the current focus of the discussions on work requirements is on the SNAP, Medicaid, and housing assistance programs. Existing SNAP law has participation requirements and includes an Employment and Training (E&T) program. It also time limits nondisabled adult recipients without children who are aged 18 to 49 and not working or participating in training to 3 months in a 36-month period.18 H.R. 2, as it passed the House, would alter those rules, establishing mandatory participation requirements for both those subject to the current time limit as well as other nondisabled adults under the age of 60.19

Medicaid has no statutory work requirements. However, the Trump Administration is currently granting research and demonstration waivers to states to permit them to require work and "community engagement" for Medicaid recipients. Under statute, these waivers must promote the objective of Medicaid, and thus must have a goal of improving health outcomes. As waivers, rather than program rules, they may differ in the population covered, the work requirements tested, and other provisions (e.g., coverage of health-related services such as enhanced dental and vision benefits, cost sharing). Generally, waivers may be granted to require engagement of nonelderly, nonpregnant individuals who are not disabled.20

In the housing assistance programs, a community service or self-sufficiency activity requirement applies to recipients in public housing. Nonexempt public housing residents must participate at least eight hours per month in community service or another activity. For Section 8 housing voucher recipients, public housing authorities participating in the Moving to Work (MTW) demonstration project are permitted to impose work requirements. Though MTW is called a demonstration, it was not designed to be evaluated.

There are numerous differences between the evaluated pre-1996 experiments and SNAP, Medicaid, and housing assistance that affect the applicability of the experiments' findings to these latter programs:

- Broader populations. SNAP, Medicaid, and housing assistance programs aid a broader population than did AFDC, as most recipients of AFDC were single mothers. In addition to general disadvantages such as low levels of education and work experience, single mothers faced a specific barrier of needing to find care for their young children. SNAP, Medicaid, and housing assistance serve a broader population of low-income individuals, such as married couples with and without children, noncustodial parents, and single men and women who are not parents. Some in these groups might also have specific barriers (e.g., the formerly incarcerated [who are often men] might have difficulty being hired because of their criminal record).

- Working low-income people. AFDC rules required the earnings of those who had them to be very low in order to come onto the rolls, and they limited the time that recipients with substantial earnings could remain on assistance. Thus, AFDC generally served nonworking single parents. SNAP, Medicaid, and housing assistance serve lower-income individuals and families, but their income eligibility thresholds are higher than those for cash assistance. Thus, many of these programs serve individuals who are working, albeit at relatively low wages and sometimes with irregular and less than full-time work schedules.

- Different goals. The goals of the evaluated pre-1996 experiments involved moving nonworking AFDC recipients into work. Programs such as SNAP, housing assistance, and Medicaid have some recipients who do not work and are disconnected from the labor force, similar to AFDC recipients. However, as noted above, these programs also have recipients who are already working. Thus, the goals of work requirements and work programs for working recipients would differ from those of the evaluated programs that focused on nonworking recipients. For example, a goal might be to increase wage rates or number of hours worked, in order to reduce assistance payments or raise incomes so the participant no longer qualifies for benefits. Additionally, the Medicaid waivers are being granted with the goal of improving the health of the population covered by them, a different goal than connecting recipients to work.

- Different approaches to employment and education services. Among the SNAP, housing assistance, and Medicaid programs, only SNAP has a funding mechanism for providing employment and educational services to its recipients. Housing and Medicaid lack funding for such services. Under the Trump Administration's "community engagement" waiver initiative, Medicaid funds can be used by states to enforce compliance with the work and community engagement requirement, but not for employment and training services themselves.

Conclusion

The welfare reform debates that culminated in the 1996 welfare reform law occurred simultaneously with a large number of studies fielded in the 1980s and early 1990s testing work requirements and employment and education services for adult recipients of cash assistance for needy families (mostly single mothers). The accumulated evidence showed that mandatory welfare-to-work programs—the combination of funded employment and education services with mandatory participation requirements—could achieve some limited policy goals, increase employment, and reduce welfare receipt. It also showed a policy trade-off. Mandatory welfare-to-work programs alone did not increase incomes and reduce poverty. However, programs that supplemented mandatory participation in a welfare-to-work program with continued aid for working parents sometimes increased incomes, though at a cost to the government.

As Congress debates work requirements in SNAP, Medicaid, and housing assistance, there is no large accumulated research base to draw from. Given the differences in populations, presence of those in the programs who are already working, goals, and funding structures for employment and education services, the findings of the pre-1996 welfare-to-work experiments cannot be directly applied to the current debate.

The lack of a research base on the effectiveness of work requirements for SNAP recipients led to Congress requiring pilot work programs in the 2014 Farm Bill (P.L. 113-79). That law authorized pilots in 10 states. In March 2015, the U.S. Department of Agriculture awarded grants to California, Delaware, Georgia, Illinois, Kansas, Kentucky, Mississippi, Vermont, Virginia, and Washington. These pilots were fully operational beginning in FY2017. The pilots will be evaluated using the RCT method, but research findings are not yet available.21 Congress has proceeded with a 2018 Farm Bill (H.R. 2) without these results.

In tying work requirements to benefit programs, Congress might consider what goals can be achieved by such requirements, welfare-to-work programs, and/or broader labor market policies. A key finding of the pre-1996 welfare-to-work experiments was that it was work requirements and employment and education services combined with earnings supplements that both raised rates of employment and improved the economic outcomes of single mothers with children. Today, most earnings supplements are provided through the federal income tax code—the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and the partially refundable child tax credit. Most of the benefits of the EITC and all of the benefits of the child tax credit go to families with children.22 Individuals and families without children, populations that are part of the focus of work requirements for SNAP, Medicaid, and housing assistance recipients, qualify for only a small EITC.

Other labor market policies could also be considered.23 Over time, wages have increased at the top of the income distribution but have stagnated for those at the bottom, and they have fallen for those with less educational attainment.24 Absent earnings supplements or other labor market policies, the stagnant or declining fortunes for a large share of the workforce will likely constrain the effectiveness of welfare-to-work initiatives in producing long-term impacts to improve employment and economic well-being of program participants.