Introduction and Background

The federal child nutrition programs provide assistance to schools and other institutions in the form of cash, commodity food, and administrative support (such as technical assistance and administrative funding) based on the provision of meals and snacks to children.1 In general, these programs were created (and amended over time) to both improve children's nutrition and provide support to the agriculture economy.

Today, the child nutrition programs refer primarily to the following meal, snack, and milk reimbursement programs (these and other acronyms are listed in Appendix A):2

- National School Lunch Program (NSLP) (Richard B. Russell National School Lunch Act (42 U.S.C. 1751 et seq.));

- School Breakfast Program (SBP) (Child Nutrition Act, Section 4 (42 U.S.C. 1773));

- Child and Adult Care Food Program (CACFP) (Richard B. Russell National School Lunch Act, Section 17 (42 U.S.C. 1766));

- Summer Food Service Program (SFSP) (Richard B. Russell National School Lunch Act, Section 13 (42 U.S.C. 1761)); and

- Special Milk Program (SMP) (Child Nutrition Act, Section 3 (42 U.S.C. 1772)).

The programs provide financial support and/or foods to the institutions that prepare meals and snacks served outside of the home (unlike other food assistance programs such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program [SNAP, formerly the Food Stamp Program] where benefits are used to purchase food for home consumption). Though exact eligibility rules and pricing vary by program, in general the amount of federal reimbursement is greater for meals served to qualifying low-income individuals or at qualifying institutions, although most programs provide some subsidy for all food served. Participating children receive subsidized meals and snacks, which may be free or at reduced price. Forthcoming sections discuss how program-specific eligibility rules and funding operate.

This report describes how each program operates under current law, focusing on eligibility rules, participation, and funding. This introductory section describes some of the background and principles that generally apply to all of the programs; subsequent sections go into further detail on the workings of each.

Unless stated otherwise, participation and funding data come from USDA-FNS's "Keydata Reports."3

Authorization and Reauthorization

The child nutrition programs are most often dated back to the 1946 enactment of the National School Lunch Act, which created the National School Lunch Program, albeit in a different form than it operates today.4 Most of the child nutrition programs do not date back to 1946; they were added and amended in the decades to follow as policymakers expanded child nutrition programs' institutional settings and meals provided:

- The Special Milk Program was created in 1954, regularly extended, and made permanent in 1970.5

- The School Breakfast Program was piloted in 1966, regularly extended, and eventually made permanent in 1975.6

- A program for child care settings and summer programs was piloted in 1968, with separate programs authorized in 1975 and then made permanent in 1978.7 These are now the Child and Adult Care Food Program8 and Summer Food Service Program.

- The Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Program began as a pilot in 2002, was made permanent in 2004, and was expanded nationwide in 2008.9

The programs are now authorized under three major federal statutes: the Richard B. Russell National School Lunch Act (originally enacted as the National School Lunch Act in 1946), the Child Nutrition Act (originally enacted in 1966), and Section 32 of the act of August 24, 1935 (7 U.S.C. 612c).10 Congressional jurisdiction over the underlying three laws has typically been exercised by the Senate Agriculture, Nutrition, and Forestry Committee; the House Education and the Workforce Committee; and, to a limited extent (relating to commodity food assistance and Section 32 issues), the House Agriculture Committee.

Congress periodically reviews and reauthorizes expiring authorities under these laws. The child nutrition programs were most recently reauthorized in 2010 through the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010 (HHFKA, P.L. 111-296); some of the authorities created or extended in that law expired on September 30, 2015.11 WIC (the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children) is also typically reauthorized with the child nutrition programs. WIC is not one of the child nutrition programs and is not discussed in this report.12

The 114th Congress began but did not complete a 2016 child nutrition reauthorization (see CRS Report R44373, Tracking the Next Child Nutrition Reauthorization: An Overview). As of the date of this report, the committees of jurisdiction have not conducted reauthorization hearings or markups in the 115th Congress.

Program Administration: Federal, State, and Local

The U.S. Department of Agriculture's Food and Nutrition Service (USDA-FNS) administers the programs at the federal level. The programs are operated by a wide variety of local public and private providers and the degree of direct state involvement differs by program and state.13 At the state level, education, health, social services, and agriculture departments all have roles; at a minimum, they are responsible for approving and overseeing local providers such as schools, summer program sponsors, and child care centers and day care homes, as well as making sure they receive the federal support they are due. At the local level, program benefits are provided to millions of children (e.g., there were 30.0 million in the National School Lunch Program, the largest of the programs, in FY2017), through some 100,000 public and private schools and residential child care institutions, nearly 170,000 child care centers and family day care homes, and just over 50,000 summer program sites.

All programs are available in the 50 states and the District of Columbia. Virtually all operate in Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Virgin Islands (and, in differing versions, in the Northern Marianas and American Samoa).14

Funding Overview

This section summarizes the nature and extent to which the programs' funding is mandatory and discretionary, including a discussion of appropriated entitlement status. Table 3 lists child nutrition program and related expenditures.

Open-Ended, Appropriated Entitlement Funding

Most spending for child nutrition programs is provided in annual appropriations acts to fulfill the legal financial obligation established by the authorizing laws. That is, the level of spending for such programs, referred to as appropriated mandatory spending, is not controlled through the annual appropriations process, but instead is derived from the benefit and eligibility criteria specified in the authorizing laws. The appropriated mandatory funding is treated as mandatory spending. Further, if Congress does not appropriate the funds necessary to fund the program, eligible entities may have legal recourse.15 Congress considers the Administration's forecast for program needs in its appropriations decisions. For the majority of funding discussed in this report, the formula that controls the funding is not capped and fluctuates based on the reimbursement rates and the number of meals/snacks served in the programs.

|

Reimbursable Meals A "reimbursable meal" (or snack in the case of some programs) is a phrase used by USDA, state, and other child nutrition policy and program operators to indicate a meal (or snack) that meets federal requirements and thereby qualifies for meal reimbursement.16 In general, a meal or snack that is reimbursable means that it is

In the school meals programs (with some variation in other programs), the highest reimbursement is paid for meals served free to eligible children, a slightly lower reimbursement is paid for meals served at a reduced price to eligible children, and a much smaller reimbursement is also paid for meals served to children who are either ineligible for assistance or not certified. For this last group, the children pay the full price as advertised but meals are still technically subsidized. |

Cash Reimbursements and Commodity Foods

In the meal service programs, such as the National School Lunch Program, School Breakfast Program, summer programs, and assistance for child care centers and day care homes, federal aid is provided in the form of statutorily set subsidies (reimbursements) paid for each meal/snack served that meets federal nutrition guidelines. Although all (including full-price) meals/snacks served by participating providers are subsidized, those served free or at a reduced price to lower-income children are supported at higher rates. All federal meal/snack subsidy rates are indexed annually (each July) for inflation, as are the income eligibility thresholds for free and reduced-price meals/snacks.18 Subsequent sections discuss how a specific program's eligibility and reimbursements work.

Most subsidies are cash payments to schools or other providers, but a smaller portion of aid is provided in the form of USDA-purchased commodity foods.19 Laws for three child nutrition programs (NSLP, CACFP, and SFSP) require the provision of commodity foods (or in some cases allow cash in lieu of commodity foods).20

Meal and snack service entails nonfood costs. Federal child nutrition per-meal/snack subsidies may be used to cover local providers' administrative and operating costs. However, the separate direct federal payments for administrative/operating costs ("State Administrative Expenses," discussed in the "Related Programs, Initiatives, and Support Activities" section) are limited.

Other Federal Funding

In addition to the open-ended, appropriated entitlement funds summarized above, the child nutrition programs' funding also includes certain other mandatory funding21 and a limited amount of discretionary funding. Some of the activities discussed in "Related Programs, Initiatives, and Support Activities," such as Team Nutrition, are provided for with discretionary funding.

Aside from the annually appropriated funding, the child nutrition programs are also supported by certain permanent appropriations and transfers. Notably, funding for the Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Program is funded by a transfer from USDA's Section 32 program, a permanent appropriation of 30% of the previous year's customs receipts.

State, Local, and Participant Funds

Federal subsidies do not necessarily cover the full cost of the meals and snacks offered by providers. States and localities help cover program costs, as do children's families by paying charges for nonfree or reduced-price meals/snacks. There is a nonfederal cost-sharing requirement for the school meals programs (discussed below), and some states supplement school funding through additional state per-meal reimbursements or other prescribed financing arrangements.22

Child Nutrition Programs at a Glance

Subsequent sections of this report delve into the details of how each of the child nutrition programs support the service of meals and snacks in institutional settings; first, it is useful to take a broader perspective of primary program elements. Table 1 is a top-level look at the different programs that displays distinguishing characteristics (what meals are provided, in what settings, to what ages) and recent program spending.

|

Program |

Authorizing Statute (Year First Authorized) |

Distinguishing Characteristics |

FY2017 Expenditures |

FY2017 Average Daily Participation |

Maximum Daily Snack/Mealsa |

|||||

|

National School Lunch Program |

Richard B. Russell National School Lunch Act (1946) |

|

$13.6 billion |

30.0 million children |

One meal and snack per child |

|||||

|

School Breakfast Program |

Child Nutrition Act (1966) |

|

$4.3 billion |

14.7 million children |

Generally one breakfast per child, with some flexibility |

|||||

|

Child and Adult Care Food Program (child care centers, day care homes, adult day care centers) |

Richard B. Russell National School Lunch Act (1968) |

|

$3.5 billion (includes at-risk after-school spending, described below) |

4.4 million children; 132,000 adults |

Two meals and one snack, or one meal and two snacks per participant |

|||||

|

Child and Adult Care Food Program (At-Risk After-School snacks and meals)b |

Richard B. Russell National School Lunch Act (1994) |

|

(Not available; included in CACFP total above) |

1.7 million children (included in CACFP children above) |

One meal and one snack per child |

|||||

|

Summer Food Service Program |

Richard B. Russell National School Lunch Act (1968) |

|

$485 million |

2.7 million childrenc |

Lunch and breakfast or lunch and one snack per child Exception: maximum of three meals for camps or programs that serve primarily migrant children |

|||||

|

Special Milk Program |

Child Nutrition Act (1954) |

|

$8 million |

191,000 half-pints served (average daily)d |

Not specified |

|||||

|

Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Program |

Richard B. Russell National School Lunch Act (2002) |

|

$184e million |

Not available |

Not applicable |

Source: Except where noted, participation and funding data from USDA-FNS Keydata May 2018 report, which contains data through March 2018. Participation data are estimated by USDA-FNS based on meals served.

a. These maximums are provided in the authorizing law for CACFP and SFSP, but specified only in regulations (7 C.F.R. 210.10(a), 220.9(a)) for NSLP and SBP.

b. At-risk after-school snacks and meals are part of CACFP law and CACFP funding, but differ in their rules and the age of children served.

c. Based only on July 2017 participation data.

d. Data from p. 32-58 of FY2019 USDA-FNS Congressional Budget Justification.

e. Obligations data displayed on p. 32-14 of FY2019 USDA-FNS Congressional Budget Justification.

Links to Resources

Other relevant CRS reports in this area include23

- CRS In Focus IF10266, An Introduction to Child Nutrition Reauthorization

- CRS Report R42353, Domestic Food Assistance: Summary of Programs

- CRS Report R41354, Child Nutrition and WIC Reauthorization: P.L. 111-296 (summarizes the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010)

- CRS Report R44373, Tracking the Next Child Nutrition Reauthorization: An Overview

- CRS Report R44588, Agriculture and Related Agencies: FY2017 Appropriations

- CRS Report RL34081, Farm and Food Support Under USDA's Section 32 Program

Other relevant resources include

- USDA-FNS's website, https://www.fns.usda.gov/school-meals/child-nutrition-programs

- USDA-FNS's Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act page, http://www.fns.usda.gov/school-meals/healthy-hunger-free-kids-act

- The FNS page of the Federal Register, https://www.federalregister.gov/agencies/food-and-nutrition-service

School Meals Programs

This section discusses the school meals programs: the National School Lunch Program (NSLP) and the School Breakfast Program (SBP). Principles and concepts common to both programs are discussed first; subsections then discuss features and data unique to the NSLP and SBP, respectively.

General Characteristics

The federal school meals programs provide federal support in the form of cash assistance and USDA commodity foods; both are provided according to statutory formulas based on the number of reimbursable meals served in schools. The subsidized meals are served by both public and private nonprofit elementary and secondary schools and residential child care institutions (RCCIs)24 that opt to enroll and guarantee to offer free or reduced-price meals to eligible low-income children. Both cash and commodity support to participating schools are calculated based on the number and price of meals served (e.g., lunch or breakfast, free or full price), but once the aid is received by the school it is used to support the overall school meal service budget, as determined by the school. This report focuses on the federal reimbursements and funding, but it should be noted that some states have provided state financing through additional state-specific funding.25

Federal law does not require schools to participate in the school meals programs. However, some states have mandated that schools provide lunch and/or breakfast, and some of these states require that their schools do so through NSLP and/or SBP.26 The program is open to public and private schools.

A reimbursable meal requires compliance with federal school nutrition standards, which have changed throughout the history of the program based on nutritional science and children's nutritional needs. Food items not served as a complete meal meeting nutrition standards (e.g., a la carte offerings) are not reimbursable meals, and therefore are not eligible for federal per-meal, per-snack reimbursements. Following rulemaking to implement P.L. 111-296 provisions, the standards for reimbursable meals were updated in January 2012 and USDA also has provided nutrition standards for the nonmeal foods served in schools during the school day (see "Selected Current Issues" for more on these policies).

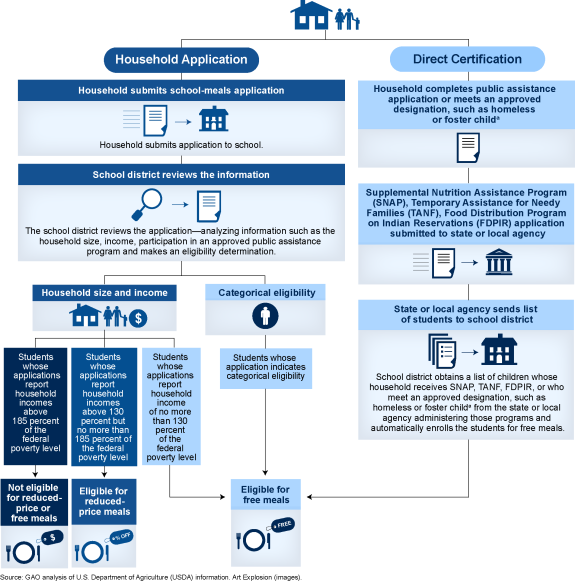

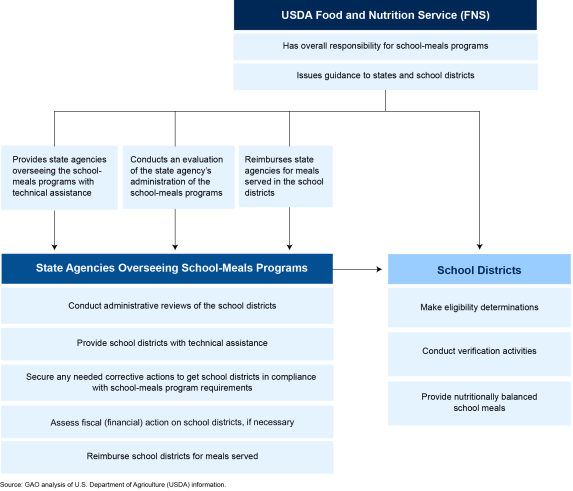

USDA-FNS administers the school meals programs federally, and state agencies (typically state departments of education) oversee and transmit reimbursements through agreements with school food authorities (SFAs) (typically local educational agencies (LEAs); usually these are school districts). Figure 1 provides an overview of the roles and relationships between these levels of government.

There is a cost-sharing requirement for the programs, which amounts to a contribution of approximately $200 million from the states.27 There also are states that choose to supplement federal reimbursements with their own state reimbursements.28

|

Figure 1. Federal, State, and Local Administration of School Meal Programs |

|

|

Source: Government Accountability Office (GAO), GAO-14-262, p. 47. |

School Meals Eligibility Rules

The school meals programs and related funding do not serve only low-income children. All students can receive a meal at a NSLP- or SBP-participating school, but how much the child pays for the meal and/or how much of a federal reimbursement the state receives will depend largely on whether the child qualifies for a "free," "reduced-price," or "paid" (i.e., advertised price) meal. Both NSLP and SBP use the same household income eligibility criteria and categorical eligibility rules. States and schools receive the largest reimbursements for free meals, smaller reimbursements for reduced-price meals, and the smallest (but still some federal financial support) for the full-price meals.

There are three pathways through which a child can become certified to receive a free or reduced-price meal:

- 1. Household income eligibility for free and reduced-price meals (information typically collected via household application),

- 2. Categorical (or automatic) eligibility for free meals (information collected via household application or a direct certification process), and

- 3. School-wide free meals under the Community Eligibility Provision (CEP), an option for eligible schools that is based on the share of students identified as eligible for free meals.29

Each of these pathways is discussed in more detail below.

Income Eligibility

The income eligibility thresholds (shown in Table 2) are based on multipliers of the federal poverty guidelines. As the poverty guidelines are updated every year, so are the eligibility thresholds for NSLP and SBP.

- Free Meals: Children receive free meals if they have household income at or below 130% of the federal poverty guidelines; these meals receive the highest subsidy rate. (Reimbursements are approximately $3.30 per lunch served, less for breakfast.)

- Reduced-Price Meals: Children may receive reduced-price meals (charges of no more than 40 cents for a lunch or 30 cents for a breakfast) if their household income is above 130% and less than or equal to 185% of the federal poverty guidelines; these meals receive a subsidy rate that is 40 cents (NSLP) or 30 cents (SBP) below the free meal rate. (Reimbursements are approximately $2.90 per lunch served.)

- Paid Meals: A comparatively small per-meal reimbursement is provided for full-price or paid meals served to children whose families do not apply for assistance or whose family income does not qualify them for free or reduced-price meals.30 The paid meal price is set by the school but must comply with federal regulations.31 (Reimbursements are approximately 30 cents per lunch served.)

The above reimbursement rates are approximate; exact current-year federal reimbursement rates for NSLP and SBP are listed in Table B-1 and Table B-3, respectively.

Households complete paper or online applications that collect relevant income and household size data, so that the school district can determine if children in the household are eligible for free meals, reduced-price meals, or neither.

Though these income guidelines primarily influence funding and administration of NSLP and SBP, they also affect the eligibility rules for the SFSP, CACFP, and SMP (described further in subsequent sections).

Table 2. Income Eligibility Guidelines for a Family of Four for NSLP and SBP

For 48 states and DC, school year 2018-2019

|

Meal Type |

Income Eligibility Threshold |

Annual Income for a |

|

Free |

<130% |

<$32,630 |

|

Reduced-Price |

130-185% |

$32,630 - $46,435 |

Source: USDA, Food and Nutrition Service, "Child Nutrition Programs: Income Eligibility Guidelines," 83 Federal Register 20788, May 8, 2018.

Note: This school year is defined as July 1, 2018, through June 30, 2019. For other years, household sizes, Alaska, and Hawaii, see USDA-FNS website: http://www.fns.usda.gov/school-meals/income-eligibility-guidelines.

Categorical Eligibility

In addition to the eligibility thresholds listed above, the school meals programs also convey eligibility for free meals based on household participation in certain other need-tested programs or children's specified vulnerabilities (e.g., foster children). Per Section 12 of the National School Lunch Act, "a child shall be considered automatically eligible for a free lunch and breakfast ... without further application or eligibility determination, if the child is"32

- in a household receiving benefits through

- SNAP (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program);

- FDPIR (Food Distribution Program on Indian Reservations, a program that operates in lieu of SNAP on some Indian reservations) benefits; or

- TANF (Temporary Assistance for Needy Families) cash assistance;

- enrolled in Head Start;

- in foster care;

- a migrant;

- a runaway; or

- homeless.33

For meals served to students certified in the above categories, the state/school will receive reimbursement at the free meal amount and children receive a free meal. (See Table B-1 and Table B-3 for school year 2018-2019 rates.)

Some school districts collect information for these categorical eligibility rules via paper application. Others conduct a process called direct certification—a proactive process where government agencies typically cross-check their program rolls and certify a household's children for free school meals without the household having to complete a school meals application.

Prior to 2004, states had the option to conduct direct certification of SNAP (then, the Food Stamp Program), TANF, and FDPIR participants. In the 2004 child nutrition reauthorization (P.L. 108-265), states were required under federal law to conduct direct certification for SNAP participants, with nationwide implementation taking effect in school year 2008-2009. Conducting direct certification for TANF and FDPIR remains at the state's discretion.

The Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010 (HHFKA; P.L. 111-296) made further policy changes to expand direct certification (discussed further in the next section). One of those changes was the initiation of a demonstration project to look at expanding categorical eligibility and direct certification to some Medicaid households. The law also funded performance incentive grants for high-performing states and authorized correcting action planning for low-performing states in direct certification activities.34

Under SNAP direct certification rules generally, schools enter into agreements with SNAP agencies to certify children in SNAP households as eligible for free school meals without requiring a separate application from the family. Direct certification systems match student enrollment lists against SNAP agency records, eliminating the need for action by the child's parents or guardians. Direct certification allows schools to make use of SNAP's more in-depth eligibility certification process; this can reduce errors that may occur in school lunch application eligibility procedures that are otherwise used.35 From a program access perspective, direct certification also reduces the number of applications a household must complete.

Figure 2, created by GAO and published in a May 2014 report, provides an overview of how school districts certify students for free and reduced-price meals under the income-based and category-based rules, via applications and direct certification.36 A USDA-FNS study of school year 2014-2015 estimates that 11.1 million students receiving free meals were directly certified—68% of all categorically eligible students receiving free meals.37

Community Eligibility Provision (CEP)

HHFKA also authorized the school meals Community Eligibility Provision (CEP), an option in NSLP and SBP law that allows eligible schools and school districts to offer free meals to all enrolled students based on the percentage of their students who are identified as automatically eligible from nonhousehold application sources (primarily direct certification through other programs).38

Based on the statutory parameters, USDA-FNS piloted CEP in various states over three school years and it expanded nationwide in school year 2014-2015. Eligible LEAs have until June 30 of each year to notify USDA-FNS if they will participate in CEP.39 According to a database maintained by the Food Research and Action Center, just over 20,700 schools in more than 3,500 school districts (LEAs) participated in CEP in SY2016-2017, an increase of approximately 2,500 schools compared to SY2015-2016.40

For a school (or school district, or group of schools within a district) to provide free meals to all children

- the school(s) must be eligible for CEP based on the share (40% or greater) of enrolled children that can be identified as categorically (or automatically) eligible for free meals, and

- the school must opt-in to CEP.

Though CEP schools serve free meals to all students, they are not reimbursed at the "free meal" rate for every meal. Instead, the law provides a funding formula: the percentage of students identified as automatically eligible (the "identified student percentage" or ISP) is multiplied by a factor of 1.6 to estimate the proportion of students who would be eligible for free or reduced-price meals had they been certified via application.41 The result is the percentage of meals served that will be reimbursed at the free meal rate, with the remainder reimbursed at the far lower paid meal rate. For example, if a CEP school identifies that 40% of students are eligible for free meals, then 64% of the meals served will be reimbursed at the free meal rate and 36% at the paid meal rate.42 Schools that identify 62.5% or more students as eligible for free meals receive the free meal reimbursement for all meals served.

Some of the considerations that may impact a school's decision to participate in CEP include whether the new funding formula would be beneficial for their school meal budget; an interest in reducing paperwork for families and schools; and an interest in providing more free meals, including meals to students who have not participated in the program before.

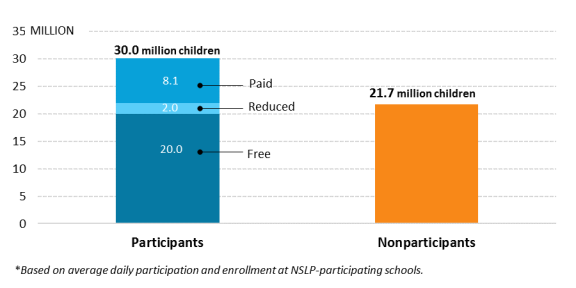

National School Lunch Program (NSLP)

In FY2017, NSLP subsidized 4.9 billion lunches to children in close to 96,000 schools and 3,200 residential child care institutions (RCCIs). Average daily participation was 30.0 million students (58% of children enrolled in participating schools and RCCIs). Of the participating students, 66.7% (20.0 million) received free lunches and 6.5% (2.0 million) received reduced-price lunches. The remainder were served full-price meals, though schools still receive a reimbursement for these meals. Figure 3 shows FY2017 participation data.

FY2017 federal school lunch costs totaled approximately $13.6 billion (see Table 3 for the various components of this total). The vast majority of this funding is for per-meal reimbursements for free and reduced-price lunches.

HHFKA also provided an additional 6-cent per-lunch reimbursement to schools that provide meals that meet the updated nutritional guidelines requirements.43 This bonus is not provided for breakfast, but funds may be used to support schools' breakfast programs. NSLP lunch reimbursement rates are listed in Table B-1.

In addition to federal cash subsidies, schools participating in NSLP receive USDA-acquired commodity foods. Schools are entitled to a specific, inflation-indexed value of USDA commodity foods for each lunch they serve. Also, schools may receive donations of bonus commodities acquired by USDA in support of the farm economy.44 In FY2017, the value of federal commodity food aid to schools totaled nearly $1.4 billion. The per-meal rate for commodity food assistance is included in Table B-4.

While the vast majority of NSLP funding is for lunches served during the school day, NSLP may also be used to support snack service during the school year and to serve meals during the summer. These features are discussed in subsequent sections, "Summer Meals" and "After-School Meals and Snacks: CACFP, NSLP Options." Reimbursement rates for snacks are listed in Table B-2.

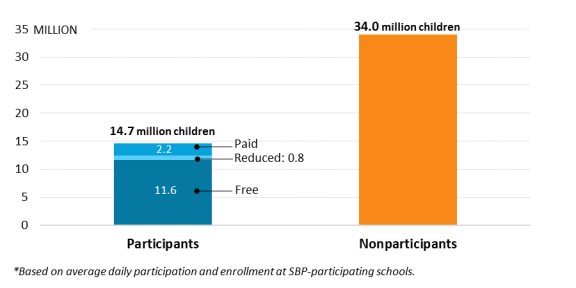

School Breakfast Program (SBP)

The School Breakfast Program (SBP) provides per-meal cash subsidies for breakfasts served in schools. Participating schools receive subsidies based on their status as a severe need or nonsevere need institution. Schools can qualify as a severe need school if 40% or more of their lunches are served free or at reduced prices. See Table B-3 for SBP reimbursement rates.

Figure 4 displays SBP participation data for FY2017. In that year, SBP subsidized over 2.4 billion breakfasts in over 88,000 schools and nearly 3,200 RCCIs. Average daily participation was 14.7 million children (30.1% of the students enrolled in participating schools and RCCIs). The majority of meals served through SBP are free or reduced-price. Of the participating students, 79.1% (11.6 million) received free meals and 5.7% (835,000) purchased reduced-price meals. Federal school breakfast costs for the fiscal year totaled approximately $4.3 billion (see Table 3 for the various components of this total).

Significantly fewer schools and students participate in SBP than in NSLP. Participation in SBP tends to be lower for several reasons, including the traditionally required early arrival by students in order to receive a meal and eat before school starts. Some schools offer (and anti-hunger groups have encouraged) models of breakfast service that can result in greater SBP participation, such as Breakfast in the Classroom, where meals are delivered in the classroom; "grab and go" carts, where students receive a bagged breakfast that they bring to class, or serving breakfast later in the day in middle and high schools.45

Unlike NSLP, commodity food assistance is not a formal part of SBP funding; however, commodities provided through NSLP may be used for school breakfasts as well.

Other Child Nutrition Programs

In addition to the school meals programs discussed above, other federal child nutrition programs provide federal subsidies and commodity food assistance for schools and other institutions that offer meals and snacks to children in early childhood, summer, and after-school settings. This assistance is provided to (1) schools and other governmental institutions, (2) private for-profit and nonprofit child care centers, (3) family/group day care homes, and (4) nongovernmental institutions/organizations that offer outside-of-school programs for children. (Although this report focuses on the programs that serve children, one child nutrition program [CACFP] also serves day care centers for chronically impaired adults and elderly persons under the same general per-meal/snack subsidy terms.) The programs in the sections to follow serve comparatively fewer children and spend comparatively fewer federal funds than the school meal programs.

Child and Adult Care Food Program (CACFP)

CACFP subsidizes meals and snacks served in early childhood, day care, and after-school settings. CACFP provides subsidies for meals and snacks served at participating nonresidential child care centers, family day care homes, and (to a lesser extent) adult day care centers.46 The program also provides assistance for meals served at after-school programs. CACFP reimbursements are available for meals and snacks served to children age 12 or under, migrant children age 15 or under, children with disabilities of any age, and, in the case of adult care centers, chronically impaired and elderly adults. Children in early childhood settings are the overwhelming majority of those served by the program.

CACFP provides federal reimbursements for breakfasts, lunches, suppers, and snacks served in participating centers (facilities or institutions) or day care homes (private homes). The eligibility and funding rules for CACFP meals and snacks depend first on whether the participating institution is a center or a day care home (the next two sections discuss the rules specific to centers and day care homes). According to FY2017 CACFP data, child care centers have an average daily attendance of about 56 children per center, day care homes have an average daily attendance of approximately 7 children per home, and adult day care centers typically care for an average of 48 chronically ill or elderly adults per center.47

Subsidized CACFP meals and snacks must meet program-specific federal nutrition standards, and providers must demonstrate that they comply with government-established standards for other child care programs. Like in school meals, federal assistance is made up overwhelmingly of cash reimbursements calculated based on the number of meals/snacks served and federal per-meal/snack reimbursements rates, but a far smaller share of federal aid (4.3% in FY2017) is in the form of federal USDA commodity foods (or cash in lieu of foods). Federal CACFP reimbursements flow to individual providers either directly from the administering state agency (this is the case with many child/adult care centers able to handle their own CACFP administrative functions) or through "sponsors" who oversee and provide administrative support for a number of local providers (this is the case with some child/adult care centers and with all day care homes).48

In FY2017, total CACFP spending was over $3.5 billion, including cash reimbursement, commodity food assistance, and costs for sponsor audits. (See Table 3 for a further breakdown of CACFP costs.) This total also includes the after-school meals and snacks provided through CACFP's "at-risk after-school" pathway; this aspect of the program is discussed later in "After-School Meals and Snacks: CACFP, NSLP Options."

CACFP at Centers

Participation

Child care centers in CACFP can be (1) public or private nonprofit centers, (2) Head Start centers, (3) for-profit proprietary centers (if they meet certain requirements as to the proportion of low-income children they enroll), and (4) shelters for homeless families. Adult day care centers include public or private nonprofit centers and for-profit proprietary centers (if they meet minimum requirements related to serving low-income disabled and elderly adults).49 In FY2017, over 65,000 child care centers with an average daily attendance of over 3.6 million children participated in CACFP. Over 2,700 adult care centers served nearly 132,000 adults through CACFP.

Eligibility and Administration

Participating centers may receive daily reimbursements for up to either two meals and one snack or one meal and two snacks for each participant, so long as the meals and snacks meet federal nutrition standards.

The eligibility rules for CACFP centers largely track those of NSLP: children in households at or below 130% of the current poverty line qualify for free meals/snacks while those between 130% and 185% of poverty qualify for reduced-price meals/snacks (see Table 2). In addition, participation in the same categorical eligibility programs as NSLP as well as foster child status convey eligibility for free meals in CACFP.50 Like school meals, eligibility is determined through paper applications or direct certification processes.

Like school meals, all meals and snacks served in the centers are federally subsidized to some degree, even those that are paid. Different reimbursement amounts are provided for breakfasts, lunches/suppers, and snacks, and reimbursement rates are set in law and indexed for inflation annually. The largest subsidies are paid for meals and snacks served to participants with family income below 130% of the federal poverty income guidelines (the income limit for free school meals), and the smallest to those who have not met a means test. See Table B-5 for current CACFP center reimbursement rates.

Unlike school meals, CACFP institutions are less likely to collect per-meal payments. Although federal assistance for day care centers differentiates by household income, centers have discretion on their pricing of meals. Centers may adjust their regular fees (tuition) to account for federal payments, but CACFP itself does not regulate these fees. In addition, centers can charge families separately for meals/snacks, so long as there are no charges for children meeting free-meal/snack income tests and limited charges for those meeting reduced-price income tests.

Independent centers are those without sponsors handling administrative responsibilities. These centers must pay for administrative costs associated with CACFP out of nonfederal funds or a portion of their meal subsidy payments. For centers with sponsors, the sponsors may retain a proportion of the meal reimbursement payments they receive on behalf of their centers to cover such costs.

CACFP for Day Care Homes

Participation

CACFP-supported day care homes serve a smaller number of children than CACFP-supported centers, both in terms of the total number of children served and the average number of children per facility. Roughly 17% of children in CACFP (approximately 757,000 in FY2017 average daily attendance) are served through day care homes. In FY2017, approximately 103,000 homes (with just over 700 sponsors) received CACFP support.

Eligibility and Reimbursement

As with centers, payments to day care homes are provided for up to either two meals and one snack or one meal and two snacks a day for each child. Unlike centers, day care homes must participate under the auspices of a public or, more often, private nonprofit sponsor that typically has 100 or more homes under its supervision. CACFP day care home sponsors receive monthly administrative payments based on the number of homes for which they are responsible.51

Federal reimbursements for family day care homes differ by the home's status as "Tier I" or "Tier II." Unlike centers, day care homes receive cash reimbursements (but not commodity foods) that generally are not based on the child participants' household income. Instead, there are two distinct, annually indexed reimbursement rates that are based on area or operator eligibility criteria

- Tier I homes are located in low-income areas (defined as areas in which at least 50% of school-age and enrolled children qualify for free or reduced-price meals) or operated by low-income providers whose household income meets the free or reduced-price income standards.52 They receive higher subsidies for each meal/snack they serve.

- Tier II (lower) rates are by default those for homes that do not qualify for Tier I rates; however, Tier II providers may seek the higher Tier I subsidy rates for individual low-income children for whom financial information is collected and verified. (See Table B-6 for current Tier I and Tier II reimbursement rates.)

Additionally, HHFKA introduced a number of additional ways (as compared to prior law) by which family day care homes can qualify as low-income and get Tier I rates for the entire home or for individual children.53

As with centers, there is no requirement that meals/snacks specifically identified as free or reduced-price be offered; however, unlike centers, federal rules prohibit any separate meal charges.

Summer Meals

Current law SFSP and the NSLP/SBP Seamless Summer Option provide meals in congregate settings nationwide; the related Summer Electronic Benefits Transfer (SEBTC or Summer EBT) demonstration project is an alternative to congregate settings. The demonstration is discussed below; proposals to expand the demonstration are discussed in "Selected Current Issues."

Summer Food Service Program (SFSP)

SFSP supports meals for children during the summer months. The program provides assistance to local public institutions and private nonprofit service institutions running summer youth/recreation programs, summer feeding projects, and camps. Assistance is primarily in the form of cash reimbursements for each meal or snack served; however, federally donated commodity foods are also offered. Participating service institutions are often entities that provide ongoing year-round service to the community including schools, local governments, camps, colleges and universities in the National Youth Sports program, and private nonprofit organizations like churches.

Similar to the CACFP model, sponsors are institutions that manage the food preparation, financial, and administrative responsibilities of SFSP. Sites are the places where food is served and eaten. At times, a sponsor may also be a site. State agencies authorize sponsors, monitor and inspect sponsors and sites, and implement USDA policy. Unlike CACFP, sponsors are required for an institution's participation in SFSP as a site.

Participation

In FY2017, nearly 5,500 sponsors with 50,000 food service sites participated in the SFSP and served an average of approximately 2.7 million children daily (according to July data).54

Participation of sites and children in SFSP has increased in recent years. Program costs for FY2017 totaled over $485 million, including cash assistance, commodity foods, administrative cost assistance, and health inspection costs.

Eligibility and Administration

There are several options for eligibility and meal/snack service for SFSP sponsors (and their sites)

- Open sites provide summer food to all children in the community. These sites are certified based on area eligibility measures, where 50% or more of area children have family income that would make them eligible for free or reduced-price school meals (see Table 2).

- Closed or Enrolled sites provide summer meals/snacks free to all children enrolled at the site. The eligibility test for these sites is that 50% or more of the children enrolled in the sponsor's program must be eligible for free or reduced-price school meals based on household income. Closed/enrolled sites may also become eligible based on area eligibility measures noted above.

- Summer camps (that are not enrolled sites) receive subsidies only for those children with household eligibility for free or reduced-price school meals.

- Other programs specified in law, such as the National Youth Sports Program and centers for homeless or migrant children.

Summer sponsors get operating cost (food, storage, labor) subsidies for all meals/snacks they serve—up to one meal and one snack, or two meals per child per day.55 In addition, sponsors receive payments for administrative costs, and states are provided with subsidies for administrative costs and health and meal-quality inspections. See Table B-7 for current SFSP reimbursement rates. Actual payments vary slightly (e.g., by about 5 cents for lunches) depending on the location of the site (e.g., rural vs. urban) and whether meals are prepared on-site or by a vendor.

School Meals' Seamless Summer Option56

Although SFSP is the child nutrition program most associated with providing meals during summer months, it is not the only program option for providing these meals and snacks. The Seamless Summer Option, run through NSLP or SBP programs, is also a means through which food can be provided to students during summer months. Much like SFSP, Seamless Summer operates in summer sites (summer camps, sports programs, churches, private nonprofit organizations, etc.) and for a similar duration of time. Unlike SFSP, schools are the only eligible sponsors, although schools may operate the program at other sites. Reimbursement rates for Seamless Summer meals are the same as current NSLP/SBP rates.

Summer EBT for Children Demonstration

Beginning in summer 2011 and (as of the date of this report) each summer since, USDA-FNS has operated Summer Electronic Benefit Transfer for Children (SEBTC or "Summer EBT") demonstration projects in a limited number of states and Indian Tribal Organizations (ITOs). These Summer EBT projects provide electronic food benefits over summer months to households with children eligible for free or reduced-price school meals. Depending on the site and year, either $30 or $60 per month is provided, through a WIC or SNAP EBT card model. In the demonstration projects, these benefits were provided as a supplement to the Summer Food Service Program (SFSP) meals available in congregate settings.

Summer EBT and other alternatives to congregate meals through SFSP were first authorized and funded by the FY2010 appropriations law (P.L. 111-80). Although a number of alternatives were tested and evaluated, findings from Summer EBT were among the most promising, and Congress provided subsequent funding.57 Summer EBT evaluations (discussed later in "Alternatives to "Congregate Feeding" in Summer Meals") showed significant impacts on reducing child food insecurity and improving nutritional intake.58 Summer EBT was funded by P.L. 111-80 in the summers from 2011 to 2014. Projects have continued to operate and were annually funded by FY2015-FY2018 appropriations; most recently, the FY2018 appropriations law (P.L. 115-141) provided $28 million. According to USDA-FNS, in summer 2016 Summer EBT served over 209,000 children in nine states and two tribal nations—an increase from the 11,400 children served when the demonstration began in summer 2011.59

Special Milk Program (SMP)

Schools (and institutions like summer camps and child care facilities) that are not already participating in the other child nutrition programs can participate in the Special Milk Program. Schools may also administer SMP for their part-day sessions for kindergartners or pre-kindergartners.

Under SMP, participating institutions provide milk to children for free and/or at a subsidized paid price, depending on how the enrolled institution opts to administer the program (see Table B-8 for current Special Milk reimbursement rates for each of these options)

- An institution that only sells milk will receive the same per-half pint federal reimbursement for each milk sold (approximately 20 cents).

- An institution that sells milk and provides free milk to eligible children (income eligibility is the same as free school meals, see Table 2), receives a reimbursement for the milk sold (approximately 20 cents) and a higher reimbursement for the free milks.

- An institution that does not sell milk provides milk free to all children and receives the same reimbursement for all milk (approximately 20 cents). This option is sometimes called nonpricing.

In FY2017, over 41 million half-pints were subsidized, 9.5% of which were served free. Federal expenditures for this program were approximately $8.3 million in FY2017.

Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Program (FFVP)

States receive formula grants through the Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Program, under which state-selected schools receive funds to purchase and distribute fresh fruit and vegetable snacks to all children in attendance (regardless of family income). Money is distributed by a formula under which about half the funding is distributed equally to each state and the remainder is allocated by state population. States select participating schools (with an emphasis on those with a higher proportion of low-income children) and set annual per-student grant amounts (between $50 and $75).

Funding is set by law at $150 million for school year 2011-2012 and inflation-indexed for every year after. In FY2017, states used approximately $184 million in FFVP funds.60 FFVP is funded by a mandatory transfer of funds from USDA's Section 32 program—a permanent appropriation of 30% of the previous year's customs receipts.61 This transfer is required by FFVP's authorizing laws (Section 19 of the Richard B. Russell National School Lunch Act and Section 4304 of P.L. 110-246). Up until FY2018's law, annual appropriations laws delayed a portion of the funds to the next fiscal year.

After a pilot period, the Child Nutrition and WIC Reauthorization Act of 2004 (P.L. 108-265) permanently authorized and funded FFVP for a limited number of states and Indian reservations.62 In recent years, FFVP has been amended by omnibus farm bill laws rather than through child nutrition reauthorizations. The 2008 farm bill (P.L. 110-246) expanded FFVP's mandatory funding, specifically providing funds through Section 32, and enabled all states to participate in the program. The 2014 farm bill (P.L. 113-79) essentially made no changes to this program but did include, and fund at $5 million in FY2014, a pilot project that requires USDA to test offering frozen, dried, and canned fruits and vegetables and publish an evaluation of the pilot. Four states (Alaska, Delaware, Kansas, and Maine) participated in the pilot in SY2014-2015 and the evaluation was published in 2017.63 Other proposals to expand fruits and vegetables offered in FFVP have been introduced in both the 114th and 115th Congress.64

Other Topics

After-School Meals and Snacks: CACFP, NSLP Options

Two of the child nutrition programs discussed in previous sections, the National School Lunch Program (NSLP) and Child and Adult Care Food Program (CACFP), provide federal support for snacks and meals served during after-school programs.65

NSLP provides reimbursements for after-school snacks; however, this option is open only to schools that already participate in NSLP. These schools may operate after-school snack-only programs during the school year, and can do so in two ways: (1) if low-income area eligibility criteria are met, provide free snacks in lower-income areas; or (2) if area eligibility criteria are not met, offer free, reduced-price, or fully paid-for snacks, based on household income eligibility (like lunches in NSLP). The vast majority of snacks provided through this program are through the first option. Through this program, approximately 206 million snacks were served in FY2017 (a daily average of nearly 1.3 million). This compares with nearly 4.9 billion lunches served (a daily average of 27.8 million).

CACFP provides assistance for after-school food in two ways. First, centers and homes that participate in CACFP and provide after-school care may participate in traditional CACFP (the eligibility and administration described earlier). Second, centers in areas where at least half the children in the community are eligible for free or reduced-price school meals can opt to participate in the CACFP At-Risk Afterschool program, which provides free snacks and suppers. Expansion of the At-Risk After-School meals program was a major policy change included in HHFKA. Prior to the law, 13 states were permitted to offer CACFP At-Risk After-School meals (instead of just a snack); the law allowed all CACFP state agencies to offer such meals.66 In FY2017, the At-Risk Afterschool program served a total of approximately 242.6 million free meals and snacks to a daily average of more than 1.7 million children.67

|

Program or Program Component |

FY2016 |

FY2017 |

Change from FY2016 to FY2017 |

|

|

National School Lunch Program |

$13,569 |

$13,643 |

+$74 |

+1% |

|

free meal reimbursements |

$9,593 |

$9,620 |

+$27 |

0% |

|

reduced-price meal reimbursements |

$808 |

$783 |

-$25 |

-3% |

|

paid meal reimbursements |

$1,478 |

$1,480 |

+$2 |

0% |

|

additional funding to schools with more than 60% free or reduced-price participation |

$76 |

$74 |

-$2 |

-3% |

|

performance-based meal reimbursements |

$302 |

$293 |

-$9 |

-3% |

|

commodity food assistancea |

$1,311 |

$1,393 |

+$82 |

+6% |

|

School Breakfast Program |

$4,213 |

$4,252 |

+$39 |

+1% |

|

free meal reimbursements |

$3,868 |

$3,912 |

+$44 |

+1% |

|

reduced-price meal reimbursements |

$239 |

$235 |

-$4 |

-2% |

|

paid meal reimbursements |

$106 |

$106 |

$0 |

0% |

|

Child and Adult Care Food Program |

$3,520 |

$3,537 |

+$17 |

0% |

|

meal reimbursements at child care centers |

$2,307 |

$2,363 |

+$56 |

+2% |

|

meal reimbursements at child care homes |

$764 |

$721 |

-$42 |

-6% |

|

meal reimbursements at adult day care centers |

$149 |

$156 |

+$7 |

+5% |

|

commodity food assistancea |

$155 |

$153 |

-$2 |

-1% |

|

administrative costs for child care sponsors |

$146 |

$145 |

-$1 |

-1% |

|

Summer Food Service Program |

$478 |

$485 |

+$7 |

+1% |

|

meal reimbursements |

$419 |

$424 |

+$5 |

+1% |

|

commodity food assistancea |

$2 |

$2 |

$0 |

0% |

|

sponsor and inspection costs |

$58 |

$60 |

+$2 |

+3% |

|

Special Milk Program |

$9 |

$8 |

-$1 |

-11% |

|

Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Programb |

$167 |

$184 |

+$17 |

+10% |

|

State Administrative Expenses |

$260 |

$279 |

+$19 |

+7% |

|

Mandatory Other Program Costsc |

$59 |

$83 |

+$24 |

+41% |

|

Discretionary Activitiesd |

$69 |

$63 |

-$6 |

-9% |

|

TOTAL OF FUNDS DISPLAYEDe |

$22,344 |

$22,534 |

+$192 |

+1% |

Source: Program expenditures data (outlays) from USDA-FNS Keydata Reports (dated March 2017 and March 2018), except where noted below.

Notes: Expenditures displayed here will vary from displays in CRS appropriations reports and in some cases the USDA-FNS annual budget justification. Since the majority of program funding is for open-ended entitlements, expenditure data capture spending better than the total of appropriations. This table includes some functions that are funded through permanent appropriations or transfers (i.e., funding not provided in appropriations laws). Due to rounding to the nearest million, percentage increases or decreases may be exaggerated or understated.

a. Amounts included in this table for commodity food assistance include only entitlement commodities for each program, not bonus commodities.

b. Obligations data displayed on p. 32-14 of FY2019 USDA-FNS Congressional Budget Justification.

c. Obligations data displayed on p. 32-12 of FY2019 USDA-FNS Congressional Budget Justification. These costs are made up of Food Safety Education, Coordinated Review, Computer Support, Training and Technical Assistance, studies, payment accuracy, and Farm to School Team.

d. Obligations data displayed on p. 32-12 of FY2019 USDA-FNS Congressional Budget Justification. These costs include Team Nutrition, the Summer EBT demonstration, and School Meal Equipment Grants.

e. This table summarizes the vast majority of child nutrition programs' federal spending but does not capture all federal costs.

Related Programs, Initiatives, and Support Activities

Federal child nutrition laws authorize and program funding supports a range of additional programs, initiatives, and activities.68

Through State Administrative Expenses funding, states are entitled to federal grants to help cover administrative and oversight/monitoring costs associated with child nutrition programs. The national amount each year is equal to about 2% of child nutrition reimbursements. The majority of this money is allocated to states based on their share of spending on the covered programs; about 15% is allocated under a discretionary formula granting each state additional amounts for CACFP, commodity distribution, and Administrative Review efforts. In addition, states receive payments for their role in overseeing summer programs (about 2.5% of their summer program aid). States are free to apportion their federal administrative expense payments among child nutrition initiatives (including commodity distribution activities) as they see fit, and appropriated funding is available to states for two years. State Administrative Expense spending in FY2017 totaled approximately $279 million.69

Team Nutrition is a USDA-FNS program that includes a variety of school meals initiatives around nutrition education and the nutritional content of the foods children eat in schools. This includes Team Nutrition Training Grants, which provide funding to state agencies for training and technical assistance, such as help implementing USDA's nutrition requirements and the Dietary Guidelines for Americans. From 2004 to 2018, Team Nutrition also included the HealthierUS Schools Challenge (HUSSC), which originated in the 2004 reauthorization of the Child Nutrition Act. HUSSC was a voluntary certification initiative designed to recognize schools that have created a healthy school environment through the promotion of nutrition and physical activity.70

Farm-to-school programs broadly refer to "efforts that bring regionally and locally produced foods into school cafeterias," with a focus on enhancing child nutrition.71 The goals of these efforts include increasing fruit and vegetable consumption among students, supporting local farmers and rural communities, and providing nutrition and agriculture education to school districts and farmers. HHFKA amended existing child nutrition programs to establish mandatory funding of $5 million per year for competitive farm-to-school grants that support schools and nonprofit entities in establishing farm-to-school programs that improve a school's access to locally produced foods.72 The FY2018 appropriations law provided an additional $5 million in discretionary funding to remain available until expended.73 Grants may be used for training, supporting operations, planning, purchasing equipment, developing school gardens, developing partnerships, and implementing farm-to-school programs. USDA's Office of Community Food Systems provides additional resources on farm-to-school issues.74

Through an Administrative Review process (formerly referred to as Coordinated Review Effort (CRE)), USDA-FNS, in cooperation with state agencies, conducts periodic on-site NSLP school compliance and accountability evaluations to improve management and identify administrative, subsidy claim, and meal quality problems.75 State agencies are required to conduct administrative reviews of all school food authorities (SFAs) that operate the NSLP under their jurisdiction at least once during a three-year review cycle.76 Federal Administrative Review expenditures were approximately $9.9 million in FY2017.

USDA-FNS and state agencies conduct many other child nutrition program support activities for which dedicated funding is provided. Among other examples, there is the Institute of Child Nutrition (ICN), which provides technical assistance, instruction, and materials related to nutrition and food service management; it receives $5 million a year in mandatory funding appropriated in statute. ICN is located at the University of Mississippi. USDA-FNS provides training on food safety education. Funding is also provided for USDA-FNS to conduct studies, provide training and technical assistance, and oversee payment accuracy.

Selected Current Issues

This section provides further information on current issues in the child nutrition programs. In particular, it provides background on (1) USDA regulations updating various nutrition standards in the child nutrition programs, (2) current and proposed alternatives to the "congregate feeding requirement" in summer meals, and (3) recent changes and proposals aimed at addressing "lunch shaming" and unpaid meal costs.

Regulations on Nutrition Standards

Since the enactment of the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010 (HHFKA; P.L. 111-296), USDA-FNS has promulgated multiple regulations, formulated various program guidance, and published many other policy documents and reports. Three of the major changes authorized by the 2010 law relate to program nutrition standards: (1) requiring an update to the nutrition standards for NSLP and SBP meals, (2) giving USDA the authority to regulate other foods sold in schools (e.g., through vending machines and cafeterias' a la carte lines) and requiring the agency to issue related nutrition standards, and (3) requiring an update to the nutrition standards in CACFP. The new nutrition standards were championed by First Lady Michelle Obama through her "Let's Move" initiative, among other groups.77

Updated Nutrition Standards for Lunch and Breakfast

Section 201 of HHFKA (P.L. 111-296) established a timeframe for USDA to promulgate regulations updating meal patterns and nutrition standards for school meal programs based on recommendations from the Institute of Medicine (IOM) (now the Health and Medicine Division) at the National Academy of Sciences.78 Schools meeting the new requirements are eligible for the increased federal subsidies (6 cents per lunch) noted above. The law also provided funding for technical assistance to help implement new meal patterns and nutrition standards.

Ultimately, following a proposed rule, comments submitted, and policy provisions enacted in the 2012 appropriations law,79 USDA-FNS issued a final rule on January 26, 2012.80 The final rule sought to align school meal patterns with the 2010 Dietary Guidelines for Americans and called for increased availability of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and low-fat or fat-free milk in school cafeterias—generally consistent with IOM's recommendations. The regulations also included calorie maximums (whereas prior guidelines had only calorie minimums) and sodium limits to phase in over time, among other requirements.81

Although the rule was finalized in January 2012, all aspects of the rule were not to be implemented immediately; for instance, some aspects of the new guidelines went into effect for school year 2014-2015, even though the rule went into effect in school year 2012-2013.82 Three aspects of the new regulations that went into effect in SY2014-2015 were: all grains served must be whole-grain-rich,83 new fruit requirements for breakfast, and the first of three sodium limits or "targets" for breakfasts and lunches (referred to as "Target 1").84

As some schools have had difficulty implementing the new guidelines, Congress and the USDA have implemented some changes or waivers regarding the 2012 final rule's whole grain, sodium, and milk requirements. FY2015, FY2016, and FY2017 appropriations laws (P.L. 113-235, P.L. 114-113, P.L. 115-31, respectively) included policies that affect the implementation of the guidelines. As of the date of this report, schools are following policies set in an interim final rule published November 30, 2017.85

Specifically, FY2015 and FY2016 appropriations laws (1) required USDA to allow states to exempt school food authorities that meet hardship requirements from the 100% whole grain requirement86 and (2) prevented USDA from implementing a reduction in sodium scheduled to take effect in school year 2017-2018 until "the latest scientific research establishes the reduction is beneficial for children." The enacted FY2017 appropriation (§747 of P.L. 115-31) contained related policy provisions. It extended the whole grain exemptions through SY2017-2018 and (using different language from past years) limited enforcement of sodium limits to Target 1 levels. In addition, a new appropriations provision was added in the FY2017 law that required USDA to allow states to grant special exemptions to serve flavored, low-fat milk (instead of only fat-free, flavored).

In May 2017, shortly before the enactment of the FY2017 appropriations law (P.L. 115-31), Secretary of Agriculture Sonny Perdue announced plans to amend the whole grain, sodium, and dairy aspects of the nutrition standards regulations in ways that were similar to the FY2017 law's provisions.87 In November 2017, USDA-FNS issued the interim final rule, which generally extends through SY2018-2019 the three changes established by FY2017 appropriations. Specifically, the interim final rule

- continues to allow states to grant waivers to the whole grain-rich requirement;

- allows schools to offer low-fat, flavored milk; and

- continues Target 1 sodium limits, delaying implementation of Target 2 sodium limits.88

The interim final rule indicated that USDA-FNS would publish a final rule in fall 2018, in time for schools to implement in SY2019-2020. As of the date of this report, this final rule has not been published. The FY2018 appropriations law (P.L. 115-141), enacted in March 2018, did not make any changes to the standards.

There were legislative proposals to change the nutrition standards on a more-permanent basis during 114th Congress deliberations to reauthorize the child nutrition programs.89 As discussed earlier, reauthorization was not completed in the 114th Congress and authorizing committees have not considered such legislative proposals in the 115th Congress.

New Nutrition Standards for All Foods Sold in Schools

In another major policy change, Section 208 of HHFKA gave USDA the authority to regulate other foods in the school nutrition environment. Sometimes called "competitive foods," this and the related regulation pertain to foods and drinks sold in a la carte lines, vending machines, snack bars and concession stands, and fundraisers.

Relying on recommendations made by a 2007 IOM report,90 USDA-FNS promulgated a proposed rule and then an interim final rule in June 2013, which went into effect for school year 2014-2015.91 The interim final rule imposed nutrition guidelines for all nonmeal foods and beverages that are sold during the school day (defined as midnight until 30 minutes after dismissal). The final rule, published on July 29, 2016, maintained the interim final rules with minor modifications. Under the final standards, these foods must meet whole-grain requirements; have certain primary ingredients; and meet calorie, sodium, and fat limits, among other requirements. Schools are limited to a list of no- and low-calorie beverages they may sell (with larger portion sizes and caffeine allowed in high schools).

Regarding fundraisers, there are no limits on fundraisers of foods that meet the interim final rule's guidelines. Fundraisers outside of the school day are not subject to the guidelines. HHFKA and the interim final rule provide states with discretion to exempt infrequent fundraisers of foods or beverages that do not meet the nutrition standards.

The rule does not limit foods brought from home, only foods sold at school during the school day. The federal standards included are a minimum standard; states and school districts are permitted to issue more stringent policies.

Updated Nutrition Standards for CACFP

Similarly, Section 221 of HHFKA required USDA to update the meal pattern for CACFP. USDA-FNS's proposed rule, published January 15, 2015, relied upon an IOM panel's recommendations and the 2010 Dietary Guidelines for Americans.92 FNS reviewed comments and incorporated feedback in the final rule, which was published on April 25, 2016.93 The updated meal patterns went into effect on October 1, 2017. The rule changes both the infant meal pattern and child/adult meal pattern in CACFP. It also revises the National School Lunch Program (NSLP) and School Breakfast Program (SBP) meal patterns for pre-kindergarten children (such changes were not included in the January 2012 final regulation discussed earlier).

Below are some examples of changes included in the final rule94

- For infant meals, changes include condensing the previously three infant age groups into two age groups, introducing solid foods at six months of age (unless otherwise requested by a parent or guardian), providing fruits and vegetables for older infants, and eliminating juice. The updated guidelines make policy changes to support breastfeeding, including providing program reimbursements when mothers come to child care centers or homes to breastfeed their infants.

- In child and adult meals, changes include separate fruit and vegetable serving requirements, as opposed to treating fruits and vegetables as one group, and limiting juice to one serving per day. The rule also requires that at least one daily serving of grains be whole-grain rich and limits the sugar in breakfast cereals and yogurts served. Milk must be low-fat or fat-free, and flavored milk cannot be served to children age five or younger. The updated standards also disallow frying as an onsite preparation method.

- "Best practices" for the different age groups were included in the rule, not as requirements for reimbursement but as examples of ideal policies to promote good nutrition and health. Examples include the "best practice" that a center or home provides mothers with a quiet, private area to breastfeed and the recommendation to limit sugar in flavored milk served to children age six and older. USDA-FNS subsequently elaborated on the best practices through policy guidance.95

Alternatives to "Congregate Feeding" in Summer Meals

In recent years, but particularly during the 114th Congress, policymakers have weighed policy options to reach more children in the summer months using alternatives to congregate meal service.

Current Law and Policy

Under current law, most food offered in summer months is provided in congregate settings through the SFSP or the NSLP's Seamless Summer Option (SSO, an option only for schools) (see "Summer Meals" section above). "Congregate" settings refer to specific sites where children come to eat while supervised. Also, for the most part, nonschool organizations that provide summer and afterschool food need to participate in two separate programs (SFSP and CACFP At-risk Afterschool).

As discussed earlier, on a pilot basis in a limited geographic area each summer since 2011, USDA has tested alternatives to SFSP and the SSO as required by law. Specifically, the 2010 Agriculture Appropriations Act (Section 749(g) of P.L. 111-80) provided $85 million in discretionary funding for "demonstration projects to develop and test methods of providing access to food for children in urban and rural areas during the summer months." The first of those demonstrations was called the Enhanced Summer Food Service Program (eSFSP), which took place in the summers of 2010 and 2012. eSFSP included four initiatives: (1) incentives for SFSP sites to lengthen operations to 40 or more days, (2) funding to add recreational or educational activities at meal sites, (3) meal delivery for children in rural areas, and (4) "food backpacks" that children could take home on weekends and holidays.

Evaluations of eSFSP were published from 2011 to 2014.96 Participation rates rose during the demonstration periods for all four initiatives. In addition, children in the meal delivery and backpack demonstrations had consistent rates of food insecurity from summer to fall (this was not measured for the other initiatives). However, the results of the evaluation should be interpreted with caution due to a small sample size and potential confounding factors.

As discussed earlier, the second demonstration, Summer Electronic Benefit Transfer for Children (SEBTC or Summer EBT), began in summer 2011 and is ongoing as of the date of this report; this program provides SNAP or WIC benefits over EBT to households with children eligible for free or reduced-price school meals. Most recently, FY2018 appropriations (P.L. 115-141) provided $28 million for the demonstration. Evaluations of Summer EBT were conducted over a three-year period from FY2011 to FY2013.97 The evaluations, which used rigorous designs, showed a significant decline in Very Low Food Security in children (VLFS-C);98 the prevalence of VLFS-C was reduced from 9.5% in the control group to 6.4% in the Summer EBT treatment group.99 Evaluations also found improvements in children's consumption of fruits, vegetables, and whole grains. Both WIC and SNAP models showed increased consumption, but increases were greater at sites operating the WIC model.100

In the summers from 2015 to 2018, USDA-FNS also offered noncongregate feeding options at outdoor summer meal sites experiencing excessive heat.101 This demonstration has not been evaluated.

Congressional Proposals

During the 114th Congress, committees of jurisdiction marked up child nutrition reauthorization bills. Both committees of jurisdiction—the Senate Committee on Agriculture, Nutrition, and Forestry and the House Committee on Education and the Workforce—reported reauthorization legislation: S. 3136 and H.R. 5003, respectively. Both proposals would have piloted or expanded a number of alternatives for feeding low-income children during the summer months. Still, there were significant differences between the reauthorization proposals' SFSP provisions.102 (There were also committee hearings and freestanding proposals related to SFSP in the 114th Congress.103)

The committees' reauthorization bills included the following policies:

- Streamlining afterschool and summer programs. Both committees' proposals would have authorized eligible institutions in selected states to operate SFSP and CACFP At-risk Afterschool sites under one application. The bills differed in the number of states that would have been eligible and the reimbursement rates used.

- Summer EBT. Both proposals addressed the provision of benefits via EBT to children who are eligible for free and reduced-price school meals over the summer months. The Senate committee would have expanded this alternative with mandatory funding. The House committee would have kept the existing pilot funded with discretionary funding. The Senate committee would have required states to provide WIC EBT, while the House committee would have allowed participating states to provide SNAP or WIC.

- Off-Site Consumption Options. Both proposals included ways for some institutions (e.g., those located in rural areas) to provide SFSP meals for consumption off-site. The bills also included temporary flexibilities for congregate feeding sites to episodically provide meals to be consumed off-site under certain conditions (e.g., extreme weather conditions).

- Other SFSP Policies. The Senate committee's bill would have authorized discretionary funding for some states to pilot the provision of three meals per day, or two meals and one snack. The House committee's proposal would have authorized USDA to award competitive grants to improve SFSP service delivery through business partnerships.

These reauthorization bills have not been reintroduced in the 115th Congress; however, there have been other legislative proposals in the 115th Congress to amend SFSP.104

Presidential Budget Proposals

The Obama Administration's FY2017 budget proposed a number of changes to SFSP. Specifically, the Administration proposed to expand Summer EBT nationwide, with a phase-in over 10 years.105 The Administration also requested $10 million for a new Summer Food Service Non-Congregate Demonstration Project.

The Trump Administration's FY2018 and FY2019 budgets did not include any new SFSP legislative proposals. The budgets requested continued funding for Summer EBT.

Unpaid Meal Charges and "Lunch Shaming"

The issue of stigmatizing a child who owes and does not pay his or her meal costs, commonly referred to as "lunch shaming," has received increased attention in recent years.106 Some practices that school districts have adopted in response to such situations include taking or throwing away a student's selected hot foods and providing an alternative cold meal (more common) to stamping students' arms and making them wear stickers (less common).107 One reason why these instances may occur is that payments for reduced-price and full-price meals are a source of revenue for school food programs (in addition to federal NSLP and SBP reimbursements). Schools have an interest in collecting this revenue from children's families to help fund operations.108

Some have pointed out that the Community Eligibility Provision (discussed earlier in this report) is a strategy to prevent unpaid meal charges by providing free meals to all children in qualifying schools.109