Background

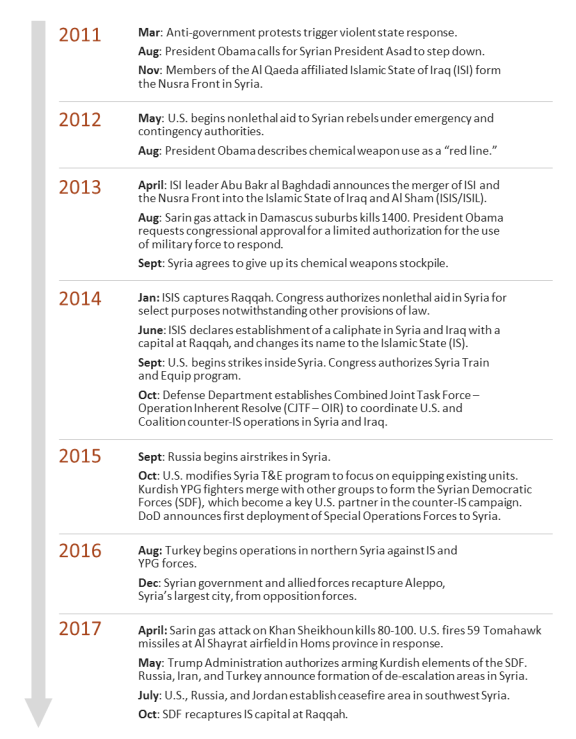

In March 2011, antigovernment protests broke out in Syria, which has been ruled by the Asad family for more than four decades. The protests spread, violence escalated (primarily but not exclusively by Syrian government forces), and numerous political and armed opposition groups emerged. In August 2011, President Barack Obama called on Syrian President Bashar al Asad to step down. Over time, the rising death toll from the conflict, and the use of chemical weapons by the Asad government, intensified pressure for the United States and others to assist the opposition. In 2013, Congress debated lethal and nonlethal assistance to vetted Syrian opposition groups, and authorized the latter. Congress also debated, but did not authorize, the use of force in response to an August 2013 chemical weapons attack.

In 2014, the Obama Administration requested authority and funding from Congress to provide lethal support to vetted Syrians for select purposes. The original request sought authority to support vetted Syrians in "defending the Syrian people from attacks by the Syrian regime," but the subsequent advance of the Islamic State organization from Syria across Iraq refocused executive and legislative deliberations onto counterterrorism. Congress authorized a Department of Defense-led train and equip program to combat terrorist groups active in Syria, defend the United States and its partners from Syria-based terrorist threats, and "promot[e] the conditions for a negotiated settlement to end the conflict in Syria."

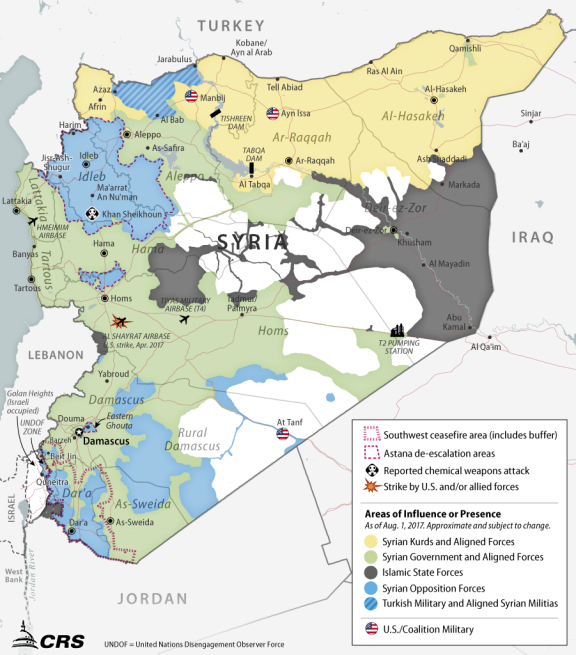

In September 2014, the United States began air strikes in Syria, with the stated goal of preventing the Islamic State from using Syria as a base for its operations in neighboring Iraq. In October 2014, the Defense Department established Combined Joint Task Force-Operation Inherent Resolve (CJTF-OIR) to "formalize ongoing military actions against the rising threat posed by ISIS in Iraq and Syria." CJTF-OIR came to encompass more than 70 countries, and has bolstered the efforts of local Syrian partner forces against the Islamic State. The United States also gradually increased the number of U.S. personnel in Syria, which reached roughly 2,000 by late 2017. President Trump in early 2018 called for an expedited withdrawal of U.S. forces from Syria,1 while other Administration officials have stated that a continued U.S. presence is key to preventing the reemergence of the Islamic State.

U.S. and coalition-backed forces in Syria succeeded in retaking, from 2015 through mid-2018, nearly all of the territory once held by the Islamic State. Meanwhile, other outside actors (Lebanese Hezbollah, Iran, and Russia) continued to support the Syrian government's military campaigns against opposition groups. Conflict between the coalition's Syrian partners and other U.S. allies has further complicated the situation, as have the growth of Al Qaeda-affiliated groups among the opposition and the ongoing humanitarian crisis. As of mid-2018, more than 5.6 million Syrians have fled to nearby countries, with six million more internally displaced inside Syria.

The collapse of IS and opposition territorial control in most of Syria since 2015 has been matched by significant military and territorial gains by the Syrian government. The U.S. intelligence community's 2018 Worldwide Threat Assessment stated in February 2018 that,

The conflict has decisively shifted in the Syrian regime's favor, enabling Russia and Iran to further entrench themselves inside the country. Syria is likely to experience episodic conflict through 2018, even as Damascus recaptures most of the urban terrain and the overall level of violence decreases.2

The U.N. has sponsored peace talks in Geneva, but it is unclear when (or whether) the parties might reach a political settlement that could result in a transition away from the leadership of the current regime. With many armed opposition groups weakened, defeated, or geographically isolated, military pressure on the Syrian government to make concessions to the opposition has been reduced. U.S. officials have stated that the United States is committed to the enduring defeat of the Islamic State and will not fund reconstruction in Asad-held areas unless a political solution is reached in accordance with U.N. Security Council Resolution 2254.3 Congress is considering legislation that would condition the use of U.S. funds in Asad-controlled areas for non-humanitarian purposes and has directed the Administration to report to Congress on its strategy.

|

|

Geography |

Size: 185,180 sq km (slightly larger than 1.5 times the size of Pennsylvania) |

|

General Demographics |

Population: 18 million (July 2017 est.) Religions: Muslim 87% (Sunni 74% and Alawi, Ismaili, and Shia 13%), Christian 10%, Druze 3% Ethnic Groups: Arab 90.3%, Kurdish, Armenian, and other 9.7% Gross Domestic Product (GDP; growth rate): $24.6 billion (2014 est.); -36.5% (2014 est.) |

|

Indicators of Humanitarian Need |

People in need of humanitarian assistance: 13.1 million Internally displaced persons: 6.6 million Syrian refugees: 5.6 million Unemployment rate: 50% (2017 est.) Population living in extreme poverty: 69% (2018 est., UNOCHA) |

|

|

Source: For sourcing and additional details, see the Appendix ("Conflict Synopsis"). |

Issues for Congress

Congress has considered the following key issues since the outbreak of the Syria conflict in 2011:

- What are the core U.S. national interests in Syria? What objectives derive from those interests? How should U.S. goals in Syria be prioritized?

- What financial, military, and personnel resources are required to implement U.S. objectives in Syria? What measures or metrics can be used to gauge progress?

- Should the U.S. military continue to operate in Syria? For what purposes and on what authority? For how long?

- How are developments in Syria affecting other countries in the region, including U.S. partners?

- What potential consequences of U.S. action or inaction should be considered? How might other outside actors respond to U.S. choices?

Amid significant territorial losses by the Islamic State and Syrian opposition groups since 2015 and parallel military gains by the Syrian government and coalition partner forces, U.S. policymakers face a number of questions and potential decision points related to:

The future of U.S. relations with the Asad government. Strained U.S.-Syria ties prior to the start of the conflict were reflected in a series of U.S. sanctions and legal restrictions that remain in place today. U.S. policy toward Syria since August 2011 has been predicated on a stated desire to see Bashar al Asad leave office, preferably through a negotiated political settlement. Nevertheless, the Asad government–backed by Russia and Iran–has reasserted control over much of western Syria since 2015, and appears poised to claim victory in the conflict. The Trump Administration has stated its intent to refrain from supporting reconstruction efforts in Syria until a political solution is reached in accordance with UNSCR 2254, which calls for constitutional reform and U.N.-supervised elections. The Trump Administration emphasizes that in its view the primary U.S. interest in Syria is achieving the enduring defeat of the Islamic State, but the Administration also identifies other goals, including reducing Iranian influence in the country, addressing issues raised by displaced Syrians, and achieving a durable solution to the underlying conflict. With Asad and his allies ascendant, Members of Congress and U.S. policy makers may consider whether future U.S. policy approaches should seek to end U.S. involvement in Syria altogether, define and proceed with conditional engagement, or contain or coerce an Asad-led Syrian government. In the short-term, discussions may focus on whether or how the Syrian government's reassertion of de facto control should affect U.S. military and assistance policy. U.S. partner forces and assistance recipients face their own difficult choices about whether or how to reconcile themselves with Asad and his backers.

U.S. military operations and the presence of U.S. military personnel in Syria. U.S. and coalition military operations against Islamic State forces in Syria continue in areas of eastern Syria close to the Iraqi border. These operations have been conducted in part at the request of Iraq's government for international military support in addressing threats emanating from Syria, in light of the Syrian government's inability or unwillingness to address those threats. With the formation of a new government in Iraq underway and the Asad government's more capable and assertive posture in Syria, some parties may seek to revisit and revise the prevailing international legal framework for ongoing coalition operations in Syria. As Administration officials proceed with new U.S. policy initiatives, Congress is also seeking clarification regarding how long U.S. military personnel will remain in Syria, for what purposes, and under what conditions they may be withdrawn.4

The future of the Syria Train and Equip program. The Islamic State has lost the vast majority of the territory it once held in Syria, and much of that territory is now controlled by U.S.-backed local forces (see Figure 3 and Figure 4). The significant reduction of IS territorial control has prompted some reevaluation of the Syria Train and Equip (T&E) program, whose primary purpose has been to support offensive campaigns against Islamic State forces. The FY2017 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) extended the program's authority through the end of 2018, but the FY2018 NDAA did not extend it further, asking instead for the Trump Administration to submit a report on its proposed strategy for Syria by February 2018. That strategy has yet to be submitted, and the FY2019 NDAA (P.L. 115-232) prohibits the obligation of FY2019 defense funds for the program until the strategy and an additional update report on train and equip efforts are submitted to Congress. The FY2019 act extends the Syria T&E authority through December 2019 but does not adjust the program's authorized scope or purposes. The Trump Administration requested $300 million in FY2019 Counter-ISIS Train and Equip Fund (CTEF) monies for Syria programs, and the House passed and Senate reported versions of the FY2019 defense appropriations act (H.R. 6157 and S. 3159) would appropriate different amounts for the account generally and for Syria programs specifically.

The future of U.S. assistance and stabilization programs. The Trump Administration has directed a reorientation in U.S. assistance programs in Syria and has sought and received new foreign contributions to support the stabilization of areas liberated from Islamic State control. The practical effect of this approach to date has been the drawdown of some assistance programs in opposition-held areas of northwestern Syria and the reprogramming of some U.S. funds appropriated by Congress for stabilization programs in Syria to other priorities. The future of U.S. assistance programs in formerly opposition-held areas of southern and southwestern Syria also is in question, in light of the Asad government's reassertion of control in these areas. As noted above, the Administration has stated its intention to end non-humanitarian assistance to Asad-controlled areas of the country until the Syrian government fulfills the terms of UNSCR 2254.

U.N. Special Envoy for Syria Staffan de Mistura said in 2017 that Syria reconstruction will cost at least $250 billion.5 The Trump Administration has stated its intent to use U.S. diplomatic influence to discourage other international assistance to government-controlled Syria in the absence of a credible political process.6 Congress may debate how the United States might best assist Syrian civilians in need, most of whom live in areas under Syrian government control, without inadvertently strengthening the Asad government or its Russian and Iranian patrons.

Select Proposed Syria-Related Legislation

In addition to provisions of FY2018 and FY2019 Foreign Operations and Defense Appropriations Acts and National Defense Authorization Acts that address some of the questions and issues described above, the 115th Congress has considered other legislation related to Syria, including:

H.R. 4681, No Assistance for Assad Act. Passed by the House in April 2018, the bill would state that it is the policy of the United States that reconstruction and stabilization assistance is to be provided only to "a democratic Syria" or to areas of Syria not controlled by the Asad government, as determined by the Secretary of State. Reconstruction aid appropriated or otherwise available from FY2019 through FY 2023 could be provided "directly or indirectly" to areas under Syrian government control only if the President certifies to Congress that the government of Syria (1) has ceased attacks against civilians and civilian infrastructure, (2) is taking steps to release all political prisoners, (3) is taking steps to remove senior officials complicit in human rights abuses, (4) is in the process of organizing free and fair elections, (5) is making progress toward establishing an independent judiciary, (6) is complying with human rights, (7) is taking steps toward fulfilling its commitments under international agreements that regulate the proliferation of chemical and nuclear weapons, (8) has halted the development and deployment of ballistic and cruise missiles, (9) is taking steps to remove government officials complicit in torture, extrajudicial killings, or chemical weapons use, (10) is reforming the military and security services to minimize the role of Iran and Iranian proxies, and (11) is in the process of securing the voluntary return of refugees and internally displaced persons.

By noting restrictions on U.S. aid provided "directly or indirectly," the bill also would limit U.S. funds that could flow into Syria via multilateral institutions and international organizations, including the United Nations, the International Monetary Fund, and the World Bank. From 2014 through 2017, appropriations acts authorized the provision of certain types of U.S. assistance to Syria for stated purposes notwithstanding any other provisions of law, without limits based on territorial control or Syrian government policy. A range of restrictions on U.S. assistance to Syria otherwise remains in place as a result of pre-conflict U.S. sanctions on the Asad government.

The bill would permit exceptions to the above restrictions on aid to government-held areas for:

projects intended to meet humanitarian needs (including food, medicine, health services, and assistance to displaced persons, refugees, and conflict victims);

assistance to further WMD disarmament projects; and

projects administered by local organizations to meet the needs of local communities.

Such projects would require the President to submit a report to appropriate congressional committees.

Additionally, the bill would require a report from the State Department and the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) describing the delivery of U.S. humanitarian assistance to Syria, including access restrictions and the monitoring and evaluation of implementing partners.

Authorization for Use of Military Force of 2018 (AUMF, S.J.Res. 59). Introduced on April 16, 2018, S.J.Res. 59 would include an authorization that is intended to provide the President the authority and flexibility he determines is necessary to carry out counterterrorism operations and protect U.S. national security by continuing to respond to the threat posed by Al Qaeda, the Islamic State, the Taliban, and other groups. It also aims to ensure that Congress exercises its legislative and oversight responsibilities with regard to its purview within the war powers enshrined in the Constitution and shared between the legislative and executive branches. Section 5(a) of S.J.Res. 59 would provide a specific list of additional designated associated forces targetable under its authorization, including Al Qaeda in Syria and the Nusra Front. The resolution would recognize Syria as a country where the use of military force is already taking place.

Caesar Syria Civilian Protection Act of 2017 (H.R. 1677). Passed by the House in May 2017, the bill updates and amends legislation (H.R. 5732) passed by the House in the 114th Congress, incorporating provisions from other proposed legislation and appearing to address some concerns expressed by various Syria policy stakeholders.

As amended, H.R. 1677 would state that "It is the policy of the United States that all diplomatic and coercive economic means should be utilized to compel the government of Bashar al-Assad to immediately halt the wholesale slaughter of the Syrian people and to support an immediate transition to a democratic government in Syria that respects the rule of law, human rights, and peaceful coexistence with its neighbors." The bill would authorize the imposition of certain sanctions by the President and amend current law to require the President to impose other sanctions on individuals he designates as eligible. The bill would require the President to submit an updated report on individuals alleged to be responsible for "serious human rights abuses" in Syria, which the bill would amend current law to define. In defining "serious human rights abuses" and requiring the Administration to report on the responsibility of dozens of named individuals for such abuses, the bill appears to create a dynamic that would make it more difficult for the executive branch to decline to designate Syrian individuals for human rights-based sanctions.

The bill would expand the potential scope of existing U.S. sanctions on Syria by making parties engaged in certain transactions with, or in support of, the government of Syria eligible for sanctions. Current executive orders impose such sanctions in some cases. The sanctions authorized in the bill could be imposed on individuals determined by the President to have met designated criteria because of knowing engagement in actions "on or after" the date of enactment. The sanctions would thus be prospective rather than retrospective. The sanctions authorized could be imposed on U.S. nationals and non-nationals. A large number of individuals are already subject to U.S. Syria-related sanctions, and in some cases individuals may already be subject to U.S. sanctions for engaging in transactions with sanctioned individuals, including entities in Russia and Iran that provide military support to the Syrian government.

The bill would require a report within 90 days assessing the potential effectiveness, risks, and operational requirements of establishing and maintaining a no-fly zone over part or all of Syria, and establishing one or more safe zones in Syria for internally displaced persons or for facilitating humanitarian assistance. It would also codify authorization for certain services in support of nongovernmental organizations' activities in Syria.

The bill includes a national security waiver and negotiation or transition scenario-specific waiver authorities for the President. Its provisions would expire after December 31, 2021.

Preventing Destabilization of Iraq and Syria Act of 2017. In January 2017, Senators Rubio and Casey introduced S. 138, known as the Preventing Destabilization of Iraq and Syria Act of 2017. They had previously introduced the bill in December 2016 as S. 3536 (114th Congress), known as the Preventing Destabilization of Iraq and Syria Act of 2016. The bill incorporated many aspects of H.R. 5732 (114th Congress), including the requirement for the imposition of sanctions on the Central Bank of Syria as well as on foreign individuals that provide support for the Syrian government or for the maintenance or expansion of natural gas and petroleum production in Syria. In addition, it would require the imposition of sanctions on Syrians complicit in the blocking of humanitarian aid.

The bill also would authorize the President to provide enhanced support for humanitarian activities in Syria, including the provision of food, shelter, water, health care, and medical supplies. It would prohibit the President from imposing sanctions on a foreign financial institution for engaging in a transaction with the Central Bank of Syria for the sale of food, medicine, medical devices, donations intended to relieve human suffering, or nonlethal aid to the people of Syria. It further would prohibit the President from imposing sanctions on internationally recognized humanitarian organizations for engaging in financial transactions related to the provision of humanitarian assistance, or for having incidental contact (in the course of providing humanitarian aid) with individuals under the control of foreign persons subject to sanctions under the act.

Recent Conflict Developments

The conflict between pro-Syrian government and opposition forces contains a variety of secondary dynamics, many of which have been exploited by outside actors. Political and armed opposition groups differ on both strategy and ideology. The opposition's Arab majority maintains a tense relationship with the most powerful Syrian Kurdish groups, which seek greater autonomy and control in significant portions of northern Syria. Armed groups have clashed with U.S.-designated foreign terrorist organizations (FTOs), which have also fought amongst themselves (the Islamic State and Al Qaeda). In addition to the United States, regional and global actors –such as Hezbollah, Iran, Russia, Turkey, and the Gulf States—have intervened in Syria, bolstering various sides in the conflict in order to further their own interests. In this process, U.S. adversaries have clashed with U.S. allies, and U.S. allies have clashed with local U.S. partners. The section below summarizes key military and political developments in the Syria conflict, but is not comprehensive.

Military

Southern Syria: Asad Retakes Southwest Ceasefire Area

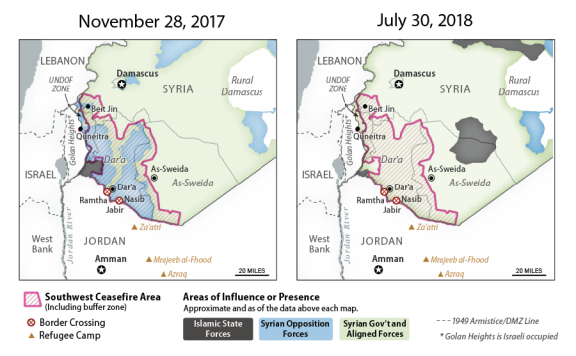

The southwest ceasefire area (also known as the southwest de-escalation zone) was established in July 2017 through an agreement between the United States, Russia, and Jordan. The area covered the majority of Dar'a province, including areas adjacent to the Israeli-occupied Golan Heights and the Jordanian border. (See Figure 5).

In the spring of 2018, dozens of armed groups operated in and around the southwest ceasefire area. These included:

The Southern Front. A coalition of roughly 50 factions which reportedly had received Western support.7

Hay'at Tahrir al Sham (HTS). A successor to the Al Qaeda-affiliated Nusra Front; designated as an FTO in May 2018. The majority of its fighters are based in the northwest province of Idlib, but the group also maintained a limited presence in Syria's southwest.

Jaysh Khaled Ibn al Walid. Established following the merger of the Yarmouk Martyrs Brigade (designated an FTO in 2016) with other local jihadist groups. Widely viewed as affiliated with the Islamic State, Jaysh Khalid Ibn al Walid was designated as an FTO in July 2017. It operated largely in in the Yarmouk Basin between Syria, Jordan, and the Golan Heights.

|

|

Source: Created by CRS. |

In May 2018, U.S. officials expressed concern about reports of an impending Syrian regime operation within the de-escalation zone, stating "As a guarantor of this de-escalation area with Russia and Jordan, the United States will take firm and appropriate measures in response to Asad regime violations."8 According to some reports, U.S. officials also privately warned Southern Front rebels not to expect U.S. backing if they broke the terms of the ceasefire agreement.9

Opposition groups surrender following Russia-brokered ceasefire deal

Following weeks of government airstrikes, artillery, and rocket attacks in the ceasefire area, some opposition forces on July 6 accepted a surrender accord brokered by Russia, and agreed to relinquish heavy weapons to the Syrian government.10 Syrian military forces also seized control of the Nasib border crossing with Jordan, which had been held by rebels since 2015. As with prior surrender agreements elsewhere in the country, oppositionists unwilling to accept renewed Asad rule were transferred to opposition-held areas of northwest Syria. The Islamic State-affiliated Jaysh Khalid Ibn al Walid was not a party to the July 6 surrender and continued to target Syrian military forces and opposition groups in Quneitra and Dar'a provinces.

Thousands of residents fled in advance of Syrian military operations in the southwest. The United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA) stated that "military activity since 17 June had originally displaced some 325,000 people, the largest displacement number recorded since the onset of the Syria crisis." 11 UNOCHA estimated that up to 184,000 remained displaced as of August 1, with the majority of these located in Quneitra province, adjacent to the Golan Heights. 12

On July 25, 2018, the Islamic State conducted a series of coordinated attacks in the provincial capital of Suweida, just east of the southwest ceasefire area. The attacks killed more than 200 people.13 On July 31, Syrian government forces recaptured the remaining portion of the southwest ceasefire area, reaching the border with the Israeli-occupied Golan Heights. The Syrian government reportedly granted safe passage to dozens of IS-affiliated fighters from Jaysh Khalid Ibn al Walid to the Badia desert area in southeastern Syria, in exchange for hostages held by the group.14 U.S. forces maintain a base of operations in the Badia area near the At Tanf border crossing with Iraq (See Figure 3).

The regional dimension. The movement of Syrian government forces towards the Israeli-occupied Golan Heights had been seen by observers as a potential flashpoint with Israel, which has sought to move Iran-backed forces further from its border. Iranian officials stated that Iran would not participate in Syrian military operations in the southwest, possibly in an effort to avoid derailing the Syrian government's campaign.15 However, some Hezbollah fighters reportedly assisted Syrian operations in the area, under the guise of Syrian military forces.16 According to some reports, Russian coordination with Israeli officials prior to the offensive was aimed at securing the latter's acquiescence to the return of Syrian military forces to the south, in exchange for the removal of Iranian-backed forces from areas near the Israeli border. 17 In July, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu stated that Israel did not object to Asad regaining control over all of Syria.18 However, Russia and Israel continue to differ on how far Iranian forces should be kept from the Israeli border.19

In August, U.N. Disengagement Observer Force (UNDOF) personnel began a planned phased return to the disengagement zone between Syria and the Israel-occupied Golan Heights. The zone had been established under the 1974 disengagement agreement between the two states. UNDOF had partially withdrawn from the disengagement zone in 2014, after extremist groups took control of some areas and kidnapped UNDOF personnel. As of mid-August, Russian military police had established four posts along the Syrian side of the disengagement zone (the Bravo line). Russian officials stated the posts–which eventually would be handed over the Syrian government–could be expanded to eight.20

Israeli Strikes in Syria

Israel has conducted several dozen air strikes inside Syria since 2012–mostly on locations and convoys near the Lebanese border associated with weapons shipments to Lebanese Hezbollah.21 In 2018, Israeli strikes have for the first time directly targeted Iranian facilities and personnel in Syria: an Israeli military source told the New York Times that a strike on April 9 was the first time Israel "attacked live Iranian targets—both facilities and people."22 In June 2018, Israel conducted a strike near Abu Kamal,23 along Syria's eastern border with Iraq. The strike was far beyond Israel's usual operational range—Israel had not struck inside Deir ez Zor province since its 2007 strike on the Al Kibar nuclear reactor.24 The June strike appeared to target Iran-backed militia fighters.

Selected Israeli Strikes in Syria in 2018

|

February 10 |

An Iranian drone crossed from Syria into Israel, where it was shot down. Israel struck the T4 (Tiyas) military base in central Syria, from which it assessed the drone was launched. Syrian anti-aircraft fire downed an Israeli F-16 participating in the operation (the plane crashed in northern Israel). Israel then struck eight Syrian and four Iranian military targets in Syria. |

|

April 9 |

Israeli F-15s struck the T4 military base in Syria, reportedly targeting a newly-arrived Iranian anti-aircraft battery and drone hangar. Iranian press stated that the strike killed seven Iranian military personnel. |

|

April 29 |

Israel struck military targets in Hamah and Aleppo provinces, reportedly killing between 16 and 26 Syrian and Iranian personnel. |

|

May 8 |

Israel struck a Syrian military facility in Al Kiswah, south of Damascus. The strike killed 15 people, reportedly including eight Iranians. |

|

May 9-10 |

After an alleged Israeli strike on a target in a Syrian town on the evening of May 9, Iranian forces in Syria fired rockets into the Israeli-occupied Golan Heights in the early morning of May 10. In response, Israel struck dozens of Iranian military targets inside Syria. Israel's defense minister stated that the strikes had targeted "almost all" of Iran's military infrastructure in Syria.25 The strikes reportedly killed 23 people. |

|

June 18 |

Israeli aircraft reportedly conducted a strike along Syria's border with Iraq.26 The strike targeted Iraqi militia in the area of Al Hurra, southeast of the Syrian border town of Abu Kamal. Kata'ib Hezbollah, a designated FTO, claimed that 22 of its fighters had been killed. The Iraqi government underscored that it had not authorized the affected militias to operate inside Syria. |

|

July 11 |

Israel's air force struck three targets in the Syrian province of Quneitra, along the Golan Heights, after a Syrian drone infiltrated Israeli airspace. 27 |

|

July 24 |

Israel shot down a Syrian Air Force aircraft near the UNDOF-patrolled disengagement zone between Syria and the Israel-occupied Golan Heights. |

|

August 2 |

An Israeli air strike killed seven individuals approaching the Golan Heights disengagement zone.28 Syrian human rights organizations described those targeted as members of the IS-affiliated Jaysh Khalid Ibn al Walid. |

|

August 4 |

Israeli responsibility was suspected in the death of Syrian scientist Aziz Asbar, who was killed in a car bombing in Masyaf, west of the provincial capital of Hamah. Asbar was affiliated with the Syrian Scientific Studies and Research Center (SSRC), which oversees Syria's chemical weapons program. According to media reports, Asbar was working alongside Iranian officials to develop production capability for precision-guided missiles inside Syria.29 |

Syrian Government Retakes Two Astana De-escalation Areas

In May 2017, Russia, Iran, and Turkey designated three opposition-held areas as "de-escalation" zones: eastern Ghouta in the Damascus suburbs, some parts of northern Homs province, and Idlib province and its surroundings. (See "The Astana Process.") The May 2017 agreement, designed to reduce violence in those areas between regime and opposition forces, allowed for states to "continue the fight" against extremist groups. Syria and Russia have traditionally labeled all groups opposing the Syrian regime as "terrorist." On that basis, they escalated military operations against opposition forces based in the de-escalation areas, and by mid-2018 had recaptured eastern Ghouta, northern Homs, and portions of Idlib province.

Eastern Ghouta

The enclave of eastern Ghouta consists of several towns within the Ghouta oasis on the outskirts of Damascus. The area's significance to the Syrian government stems from various factors including: 1) The M-5 highway (Syria's primary north-south artery) runs through it, linking the primary commercial land crossings with Jordan to Dar'a City, and onwards to Damascus 2) Prior to the war, the area supplied the capital with agricultural, manufactured, and industrial goods, and 3) Opposition groups were able to use the area to stage rocket and mortar attacks on central Damascus.

Eastern Ghouta fell under opposition control in 2012, and Syrian military forces besieged the area in 2013, limiting the ability of civilians to flee and restricting deliveries of food, medicine, and fuel.30 The Syrian military conducted numerous air strikes in the area, and in 2013 carried out a sarin gas attack that killed 1,400 people (see "Overview: Syria Chemical Weapons and Disarmament"). In October 2017, U.N. High Commissioner for Human Rights Zeid Ra'ad Al Hussein called the situation of besieged civilians in eastern Ghouta "an outrage," saying "the deliberate starvation of civilians as a method of warfare constitutes a clear violation of international humanitarian law and may amount to a crime against humanity and/or a war crime."31 In January 2018, then Secretary of State Tillerson condemned what he described as "an apparent chlorine gas attack" in eastern Ghouta.32

In February 2018, Syrian government forces intensified their attacks on eastern Ghouta in what U.N. officials described as "some of the worst fighting of the entire conflict."33 By late March, over 1,700 people had reportedly been killed and an estimated 80,000 civilians had been displaced, overwhelming the capacity of shelters in the Damascus area.34 Facing intense aerial attack, most armed groups operating in eastern Ghouta withdrew in late March under agreements negotiated by Russia. Fighters agreed to evacuate the area in exchange for safe passage to the northern province of Idlib. The withdrawal left only Douma, eastern Ghouta's largest city, under the control of opposition groups (Jaysh al Islam).

On April 7, Syrian government forces launched a suspected chemical attack on Douma, killing at least 40 people and triggering U.S. airstrikes on chemical weapons and storage sites in Syria (See "2018 Chemical Attack and U.S. Response.") On April 8, Jaysh al Islam fighters in Douma agreed to a Russian-sponsored evacuation deal granting them safe passage to the city of Jarabulus in northern Aleppo province.35 In exchange, fighters agreed to release hundreds of Syrian military prisoners of war.

Northern Homs

After capturing eastern Ghouta, the regime turned its focus to the de-escalation area in northern Homs province. The area includes the towns of Rastan and Talbiseh, strongholds of opposition support and home to many army defectors. It also includes the area around the Houla Plain, site of an early 2012 massacre. Rastan and Talbiseh sit along the portion of the M-5 highway that connects the provincial capitals of Hamah and Homs, and the opposition's hold over these towns restricted regime mobility in and through the area. Following airstrikes and shelling by Syrian military forces, a ceasefire was announced in late April, and Syrian rebels surrendered the area in early May.36 As in eastern Ghouta, fighters gave up their heavy weapons in exchange for safe passage to northern Idlib province.

Idlib: The Final Opposition Stronghold

Idlib province, in Syria's northwest, has been a stronghold of opposition support since the early months of the conflict; in June 2011 armed groups killed an estimated 120 Syrian security personnel in the city. Since then, Idlib has remained a base for opposition fighters, who seized control of the entire province in March 2015.

Al Qaeda in Idlib

Gradually, Idlib also became a base for the Nusra Front, Al Qaeda's Syrian affiliate. As government forces retreated from the province, Al Qaeda members from Afghanistan, Pakistan, and elsewhere relocated to Idlib. In 2014, U.S. officials began to refer to foreign Al Qaeda operatives in Syria as the Khorasan Group, which intelligence officials described as the "external operations arm" of the Nusra Front37 with "clear ambitions to launch external operations against the United States or Europe."38 Beginning in 2014, the United States conducted a series of airstrikes, largely in Idlib province, against Al Qaeda targets. These strikes fell outside the framework of Operation Inherent Resolve (which focuses on the Islamic State), and U.S. officials stated that they were conducted on the basis of the 2001 AUMF.39

At least a dozen foreign Al Qaeda leaders have been killed in Syria since 2014, mostly in Idlib. A February 2017 U.S. drone strike in Idlib killed the deputy leader of Al Qaeda, and a U.S. strike on an Al Qaeda training camp in Idlib the previous month killed more than a hundred AQ fighters.40 U.S. military officials in March 2017 stated that, "Idlib has been a significant safe haven for Al Qaeda in recent years."41 As of 2018, al Qaeda fighters and supporters appear to have merged into various opposition coalitions (see "Armed Coalition Groups Operating in Idlib," below).

Syrian Policy

The Syrian government has transferred thousands of Islamist and other fighters and their families to Idlib as part of surrender agreements with opposition-held towns in other parts of the country. A U.N. official in June 2018 described Idlib as a regime "dumping ground" for civilians and fighters evacuated from other opposition controlled areas.42 Syrian President Asad has stated, "…we didn't send people to Idleb; they wanted to go there," because they have the "same ideology" as the Nusra Front. He added,

...the plan of the terrorists and their masters was to distract the Syrian Army by scattering the different units all over the Syrian soil, which is not good for any army. Our plan was to put them in one area, two areas, three areas … So militarily, it is better. They chose it, but it's better for us from the military point of view.43

With the exception of northeastern Syria, which is under the control of U.S.-backed Kurdish forces, Idlib remains the last significant area still held by opposition forces. Syrian President Asad has stated that retaking Idlib is a priority. U.N. officials have expressed concern that a military offensive by Syria to retake the province could displace an additional 2.5 million people to the Turkish border, warning that, "we may have not seen the worst of the crisis."44

|

Armed Coalition Groups Operating in Idlib Hay'at Tahrir al Sham (HTS). In 2016, the Nusra Front declared a split with Al Qaeda and changed its name to Jabhat Fatah al Sham (JFS, Levant Conquest Front)—a move dismissed by U.S. government officials and other observers at the time as a rebranding effort. In 2017, JFS merged with other groups and changed its name to Hay'at Tahrir al Sham (HTS, Levant Liberation Committee). U.S. officials have stated that "The core of HTS is Nusra," 45 and amended the FTO designation of the Nusra Front in May 2018 to include HTS as an alias. However, some analysts argue that statements by Al Qaeda leader Ayman al Zawahiri and actions by Nusra and HTS members point to the emergence of a genuine rift within the two groups. This rift can be seen, they argue, in the defection of former Nusra Front members from HTS, and the arrests by HTS of senior Al Qaeda figures.46 In addition to its military operations, HTS also runs a civilian-led "Salvation Government," based in Idlib, which provides services such as education, health care, electricity, and water. National Liberation Front (NLF). In May 2018, 11 Syrian armed groups established the NLF coalition. A NLF spokesperson described the coalition as unifying a number of "Free Syrian Army factions."47 The group has been described as one of the largest coalitions fighting the Asad government, reportedly reaching nearly 30,000 fighters.48 In August, the Syrian Liberation Front (SLF), composed of fighters from armed Islamist groups Ahrar al Sham (Free Men of the Levant) and the Nour al Din Zinki Movement, merged into the NLF. Hilf Nusra al Islam. In April 2018, Horas al Din (Guardians of Religion) and Ansar al Tawhid (Supporters of Monotheism, formerly known as Jund al Aqsa, or Army of Al Aqsa) merged to form Hilf Nusra al Islam (Alliance for the Support of Islam).49 The group is viewed as sympathetic to Al Qaeda. |

The Role of External Actors

The May 2017 agreement at Astana that established the three de-escalation areas set Russia, Turkey, and Iran as guarantors. Unlike the other de-escalation areas, Idlib lies along Turkey's southern border. Idlib is also adjacent to the province of Aleppo's Afrin district, where Turkish troops currently are deployed. As a result, Turkey has played a significant role in Idlib, maintaining twelve military observation posts in and around Idlib province along the "separation line" between pro-Syrian government and opposition forces.

Turkey maintains ties with a range of Syrian opposition groups in Idlib—reportedly including HTS.50 Turkey's coordination with rebel groups in Idlib and Aleppo appears driven by Ankara's desire to minimize, if not completely roll back, Syrian YPG control of areas along its border. In turn, Syrian armed groups ally with Turkey for reasons that may include 1) material and financial support; 2) protection against the advance of Syrian military forces; and 3) an opportunity to counter perceived Kurdish expansion in traditionally Arab areas of northern Syria as part of the counter-IS campaign.

Neither Turkey nor Russia appear to support the type of expansive Syrian military operation that allowed the regime to recapture Eastern Ghouta, Homs, and the southwest ceasefire area. Turkey, which already hosts 3.5 million registered Syrian refugees, may be concerned by U.N. warnings that a Syrian military offensive in Idlib could drive a further 2.5 million refugees –including armed militants– across the border into Turkey. The Asad regime probably would favor a scenario whereby Idlib's armed Islamists were pushed into Turkey.

Russia also reportedly has concerns about the possibility of a far-reaching regime offensive in Idlib. In late July, Russia's special envoy for Syria stated that "Any large-scale operation in Idlib is out of the question."51 According to one analysis,

Given the mountainous terrain; the broadly dispersed and largely rural population; the scale of armed opposition numbers and marbled presence of experienced and committed jihadists; and the sheer size of the civilian and internally displaced population, any campaign to retake Idlib by force would likely require a far greater Russian military effort than anything Moscow has undertaken in Syria thus far.52

However, Russian officials have expressed concern about drone strikes, launched from Idlib, on their base in Lattakia, suggesting they may tolerate a more limited military campaign. Recent reports suggest that the three guarantor states have agreed that Turkey should work with other opposition groups in Idlib to eliminate militants.53 This may reflect a continuation of Turkish-backed efforts to target "hardline" HTS fighters while maintaining ties to elements of the group seen as more moderate or willing to accept Turkey's presence in Idlib for pragmatic reasons (as deterrent to Syrian government attack). 54 Turkey may seek to fracture and eventually dissolve HTS by peeling off "moderate" fighters from the group.55

Analysts have suggested that Syrian forces cannot tackle Idlib without Russian military support.56 In August, Russia's special envoy for Syria stated,

…we encouraged the moderate opposition to actively cooperate with Turkish partners and with Russia—to prevent any danger both for Russian soldiers of the Khmeimim air base and for Syrian government forces staying on the line of contact. In this case, we will not have to engage in full-blown fighting against militants.57

In 2018, the Trump Administration ended the majority of existing U.S. programming in northwest Syria, including countering violent extremism (CVE) initiatives in Idlib. (See "Trump Administration Syria Policy.")

Aleppo: Turkish Operations in Afrin; Status of Manbij

In January 2018, Turkey and affiliated Syrian armed groups launched a ground operation and air strikes in the Afrin district of northern Aleppo province. Known as Operation Olive Branch, it targeted forces from the Syrian Kurdish People's Protection Units (YPG), which have administered Afrin since 2012. Turkish officials stated that the operation aimed to stabilize the border region and eliminate PKK, YPG, and IS fighters.58 Turkey has long expressed concern about how counter-IS operations in northern Syria have effectively expanded and entrenched the YPG presence in the area, which borders southern Turkey.

|

Dispute Over PKK – YPG Ties Disagreement regarding the status of the YPG remains a key point of discord between Turkey and the United States. Turkey considers the YPG to be the Syrian branch of the PKK (Kurdistan Workers' Party), and thus a terrorist organization. (The PKK has battled the Turkish government on-and-off since the 1980s.) While both Turkey and the United States have designated the PKK a terrorist organization, the United States has not extended this designation to the YPG, which has been one of the United States' most prominent local partners in the counter-IS campaign. Turkey has accused the United States of backing a terrorist group along Turkey's southern border. |

While the YPG forms a key part of the U.S.-backed Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), U.S. military officials have stated that, "we haven't trained or provided equipment for any of the Kurds that are in the Afrin pocket."59 However, U.S. military officials also described Turkish operations around Afrin as "not helpful," stating that they distract from ongoing operations against Islamic State remnants.60 Some YPG elements battling the Islamic State in eastern Syria shifted west to Afrin following the launch of Operation Olive Branch, prompting U.S. officials in March to declare an "operational pause" in the counter-IS campaign.61

After capturing the surrounding areas, Turkish and allied Syrian groups entered the city of Afrin in March. While expressing commitment to Turkey's "legitimate security concerns," U.S. officials added that they were "deeply concerned" over reports from Afrin city that the majority of the city's population had evacuated "under threat of attack from Turkish military forces and Turkish backed opposition forces."62 The U.N. in June estimated that roughly 134,000 people remain displaced from Afrin district.63

Agreement in Manbij

U.S.-backed SDF forces recaptured the town of Manbij from the Islamic State in 2016. This was followed shortly by Turkish operations north of the city (Operation Euphrates Shield) which sealed the "Manbij pocket" border area to reduce the flow of IS foreign fighters. Turkey has repeatedly called for the departure of remaining Kurdish forces from the city. U.S. officials have described the status of the area as "a fairly tense standoff between certain opposition forces north of the Manbij area and the Syrian Democratic Forces south," noting that the United States has "helped patrol the demarcation line."64 Officials noted that tensions in Manbij increased following Turkish operations in Afrin in 2018, which brought additional refugees and armed groups into Manbij. After the Turkish-backed capture of Afrin in March, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan indicated that Turkey would push eastward toward Manbij. Later, a Pentagon spokesman said, "It's been very clear to all parties that U.S. forces are there, and we'll take measures to make sure that we de-conflict."65

On June 4, the United States and Turkey endorsed what U.S. officials described as a "broad political framework designed to fulfill the commitment that the United States had made to move the YPG east of the Euphrates."66 As part of the agreement, the United States will continue to patrol the demarcation line. Kurdish fighters who form part of the Manbij Military Council are expected to withdraw from the city, and a new Manbij council will be formed comprised of "locals who are mutually agreeable." U.S. officials stated that the aim behind the agreement "for the people of Manbij to reassert their leadership over both governance and security structures there."67

Northeast Syria: Ongoing Counter-IS Operations

On May 1, 2018, SDF forces launched the first phase of Operation Roundup, targeting IS remnants in the Middle Euphrates River valley (MERV) and the Syria-Iraq border region. In late June, Secretary Mattis stated, "Hasakah province for the first time since 2013 is now cleared of all ISIS main force element," noting the contributions of Iraqi Security Forces in those operations.68 Defense Department officials stated, "We cannot emphasize enough the contributions of the ISF in halting the movement of fighters from the battlefield and destroying targets in Syria."69

Phase two of Operation Roundup was completed in July. Coalition officials stated that the final phase of the operation will focus on clearing the last remaining pocket of IS-held territory east of the Euphrates River in Hajin, in the vicinity of Abu Kamal. Coalition officials noted that this final stage is "likely to be a challenging fight, as it is a densely populated area," and is also "one of the last holdouts of a number of foreign terrorist fighters."70 The official estimated that over a thousand IS fighters remain in the area.

U.S. officials estimate that tens of thousands of IS fighters have died in battle, but believe that approximately 30,000 current and former IS personnel may remain present in areas of Syria and Iraq, including as many as 14,500 in Syria, among whom four to six thousand may be in the northeast.71 U.N. reports make similar estimates and assessments.72 As of August 2018, coalition officials assess that fewer IS fighters are actively fighting from among this wider population, but point to their broader estimates to suggest that the group retains considerable ability to draw strength from supporters who have otherwise curtailed their activity for self-preservation or strategic reasons.73

On August 17, U.S. Special Presidential Envoy for the Global Coalition to Counter ISIS Brett McGurk said that

…the final phase to defeat the physical caliphate… is actually being prepared now and that will come at a time of our choosing, but it is coming. That will be a very significant military operation, because we have a significant number of ISIS fighters holed up in a final area of the Middle Euphrates Valley. And after that, you have to train local forces to hold the ground to make sure that the area remains stabilized so ISIS cannot return. So this mission is ongoing and is not over.74

Political Negotiations

The Geneva Process

Since 2012, the Syrian government and opposition have participated in U.N.-brokered negotiations under the framework of the Geneva Communiqué. Endorsed by both the United States and Russia, the Geneva Communiqué calls for the establishment of a transitional governing body with full executive powers. According to the document, such a government "could include members of the present government and the opposition and other groups and shall be formed on the basis of mutual consent."75 The document does not discuss the future of Asad.

Subsequent negotiations have made little progress, as both sides have adopted differing interpretations of the agreement. The opposition has said that any transitional government must exclude Asad. The Syrian government maintains that Asad was reelected (by referendum) in 2014,76 and notes that the Geneva Communiqué does not explicitly require him to step down. In the Syrian government's view, a transitional government can be achieved by simply expanding the existing government to include members of the opposition. Asad has also stated that a political transition cannot occur until "terrorism" has been defeated, which his government defines broadly to include all armed opposition groups.

As part of the Geneva Process, U.N. Security Council Resolution (UNSCR) 2254, adopted in 2015, endorsed a "road map" for a political settlement in Syria, including the drafting of a new constitution and the administration of U.N.-supervised elections. In December 2017, the U.S. Deputy Representative to the United Nations stated that, "the United States remains committed to resolution 2254 (2015) as the sole legitimate blueprint for a political resolution to this conflict."77

The last round of Geneva talks, facilitated by U.N. Envoy Staffan de Mistura, closed in late January 2018. In February, the U.S. intelligence community assessed that Asad was unlikely to negotiate a political transition with the opposition:

Moscow probably cannot force President Asad to agree to a political settlement that he believes significantly weakens him, unless Moscow is willing to remove Asad by force. While Asad may engage in peace talks, he is unlikely to negotiate himself from power or offer meaningful concessions to the opposition.78

The United States has repeatedly expressed its view that Geneva should be the sole forum for a political settlement to the Syria conflict, possibly reflecting concern regarding the Russia-led Astana Process (see below). In June 2018, the U.S. Deputy Permanent Representative to the U.N. stated, "Geneva remains the sole, legitimate venue for the peaceful resolution of the Syrian conflict. Council members around this table often reiterate this message, but actions on the ground appear to suggest that some are hedging their bets and seeking to create alternatives to Geneva."79

The Astana Process

Since January 2017, peace talks hosted by Russia, Iran, and Turkey have convened in the Kazakh capital of Astana. These talks were the forum through which several "de-escalation areas" were established (see "Cease-fires" below). The United States is not a party to the Astana talks but has attended as an observer delegation. The tenth round of Astana talks was held in July 2018 in the Russian city of Sochi.

Russia has played a leading role in the Astana process, which some have described as an alternate track to the Geneva process. The United States has strongly opposed the prospect of Astana superseding Geneva. Following the release of the Joint Statement by President Trump and Russian President Putin on November 11, 2017, U.S. officials stated that,

We have started to see signs that the Russians and the regime wanted to draw the political process away from Geneva to a format that might be easier for the regime to manipulate. Today makes clear and the [Joint Statement] makes clear that 2254 and Geneva remains the exclusive platform for the political process.80

Sochi Conference. Despite the November agreement, Russia persisted in its attempts to host, alongside Iran and Turkey, a "Syrian People's Congress" in Sochi, intended to bring together Syrian government and various opposition forces to negotiate a postwar settlement. The conference concluded on January 30, but was boycotted by most Syrian opposition groups and included mainly delegates friendly to the Asad government.81 Participants agreed to form a constitutional committee comprising delegates from the Syrian government and the opposition "for drafting of a constitutional reform," in accordance with UNSCR 2254.82 The statement noted that final agreement regarding the mandate, rules of procedure, and selection criteria for delegates would be reached under the framework of the Geneva process. The United States has supported the formation of the committee under U.N. auspices, but emphasized that "the United Nations must be given a free hand to determine the composition of the committee, its scope of work, and schedule."83

Cease-fires

Syria Southwest Cease-fire Area. In July 2017, the United States, Russia, and Jordan established a cease-fire area in southwestern Syria. The area covered parts of the Syrian provinces of Dar'a, Quneitra, and Sweida, and bordered the Golan Heights and northwestern Jordan. On November 8, 2017, the parties signed a memorandum of principles (MOP) further defining the southwest cease-fire area. The United States and Russia later issued a Joint Statement regarding the MOP and the situation in Syria. In a background briefing on the Joint Statement, State Department officials said that the MOP

...enshrines the commitment of the U.S., Russia, and Jordan to eliminate the presence of non-Syrian foreign forces. That includes Iranian forces and Iranian-backed militias like Lebanese Hizbollah as well as foreign jihadis working with Jabhat al Nusrah and other extremist groups from the southwest area.84

As described above, Syrian military operations have since targeted opposition held areas within the ceasefire area, raising questions about the parties' continued commitment to the MOP. According to the State Department, the MOP includes a commitment to "remove Iranian-backed forces a defined distance from opposition-held territory." Russia has since described the Iranian presence in Syria as legitimate, and suggested that the southwest cease-fire agreement does not imply the withdrawal of pro-Iranian forces from Syria as a whole.

Astana De-escalation Areas. As part of the Astana process, Russia, Iran, and Turkey announced in May 2017 the establishment of three "de-escalation areas" in Syria: Idlib province and its surroundings, some parts of northern Homs province, and Eastern Ghouta in the Damascus suburbs. Although the United States is not a party to the Astana Process, U.S. officials have said that they support the establishment of de-escalation areas beyond southwest Syria in principle. In 2018, the Syrian government launched military operations inside the Astana de-escalation areas and secured the disarmament and surrender of several armed opposition groups.

Dialogue between Syrian Kurds and the Asad Government

In July 2018, the Syrian Democratic Council (SDC), the political wing of the U.S.-backed Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), acknowledged that it had entered into discussions with the Syrian government. According to SDC officials, the objective of the talks was for the two sides to "work together towards a new, democratic, decentralized Syria."85 When asked whether the SDF planned to hand over areas under its control to the central government in Damascus, an SDC official stated,

One day, we want to return them to a Syrian state and not to the Syrian regime. The regime is one thing and a new Syrian state is something else. We will only return these lands to the Syrian state once we are done with setting up a new state, a new system that we will build all together through negotiations. This is what returning land to the state means.86

The Kurdish-held areas in northern Syria, comprising about a quarter of the country, are the largest remaining areas outside of Syrian government control. Asad has stated, "…the only problem left in Syria is the SDF. We're going to deal with it by two options: the first one, we started now opening doors for negotiations … This is the first option. If not, we're going to resort to liberating by force."87 Although the United States currently maintains a military presence in Kurdish areas of northern Syria, it remains unclear how long these personnel will remain. SDC officials stated, "We do not have political coordination with the US; our decision to move ahead with these talks is independent, based on the high interests of our people and our nation."88

Syrian Kurds have historically maintained a tense relationship with the central government in Damascus. Under a decades-long policy of Arabization, many Kurds were stripped of their Syrian citizenship and banned from teaching the Kurdish language in schools. Kurds lost land in "redistribution" programs that favored Arab families. In light of this, Syrian Kurds viewed the 2011 uprising as an opportunity to push for recognition of Kurdish identity and autonomy under the framework of the broader revolution. However, the majority-Arab opposition movement was largely unwilling to adopt Kurdish demands for autonomy as a goal of the uprising. Some groups, such as the Kurdish National Council, nevertheless elected to join the broader opposition movement and advocate for Kurdish interests from within. Others (such as the PYD, whose armed militia would form the backbone of the U.S.-backed SDF), chose to focus on the goal of self-determination. As the Syria conflict developed, the PYD—and its armed wing, the YPG—defended Kurdish areas from Islamic State encroachment. However, they appeared to avoid direct confrontation with Damascus, perhaps assessing that their long-term goal for self-administration in Kurdish areas was best served by avoiding such conflict.

U.S. officials have stated that Geneva is the only legitimate framework for a political settlement to the conflict. The PYD is not a party to the Geneva talks, despite the fact that its YPG militia controls the vast majority of territory held by Kurdish forces in Syria. If PYD and YPG forces reach a separate settlement with Damascus, the Syrian government may see little to gain from continued U.N. brokered talks at Geneva.

Humanitarian Situation

As of mid-2018, the United Nations estimated that 13.1 million people in Syria were in need of humanitarian assistance, out of a total estimated population of 18 million. A third of Syria's population (6.6 million) is internally displaced, and an additional nearly 5.6 million Syrians are registered with UNHCR as refugees in nearby countries.89

The Syrian government has long opposed the provision of humanitarian assistance across Syria's border and across internal lines of conflict outside of channels under Syrian government control. Successive U.N. Security Council resolutions have nevertheless authorized the provision of such assistance. The Syrian government further seeks the prompt return of Syrian refugees from neighboring countries, while humanitarian advocates and practitioners raise concern about forced returns and the protection of returnees from political persecution and the difficult conditions prevailing in Syria. In July, a State Department spokesperson said, "We support refugees going home under these conditions – safe, voluntary, dignified returns at the time of their choosing and when it is safe to do so. I don't think the situation, as UNHCR backs up right now, allows for that at this time."90

The U.N. Secretary-General regularly reports to the Security Council on humanitarian issues and challenges in and related to Syria pursuant to Resolutions 2139 (2014), 2165 (2014), 2191 (2014), 2258 (2015), 2332 (2016), 2393 (2017) and 2401 (2018).91

U.S. Humanitarian Funding

The United States is the largest donor of humanitarian assistance to the Syria crisis, drawing from existing funding from global humanitarian accounts and some reprogrammed funding.92 As of July 2018, total U.S. humanitarian assistance for the Syria crisis since 2011 has reached nearly $8.1 billion.93

The Trump Administration's FY2019 request seeks $1.78 billion in IDA-OCO funding and $2.35 billion for MRA overseas operations—these totals include funds for responses to the Iraq and Syria crises. Both the House and Senate committee reported versions of the FY2019 foreign operations appropriations act (H.R. 6385 and S. 3108) would provide amounts exceeding these requests on different terms.

International Humanitarian Funding

Multilateral humanitarian assistance in response to the Syria crisis includes both the Regional Refugee and Resilience Plan (3RP) and the Humanitarian Response Plan (HRP). The 3RP is designed to address the impact of the conflict on Syria's neighbors, and encompasses the Lebanon Crisis Response Plan, the Jordan Response Plan, and country chapters in Turkey, Iraq, and Egypt. It includes a refugee/humanitarian response coordinated by UNHCR and a "resilience" response (stabilization-based development assistance) led by UNDP.94

In parallel to the 3RP, the HRP for Syria is designed to address the crisis inside the country through a focus on humanitarian assistance, civilian protection, and increasing resilience and livelihood opportunities, in part by improving access to basic services. This includes the reconstruction of damaged infrastructure (water, sewage, electricity) as well as the restoration of medical and education facilities and infrastructure for the production of inputs for sectors such as agriculture.95 The 2017 3RP appeal sought $5.6 billion, and the HRP for Syria sought $3.4 billion. By the end of 2017, the two appeals had been funded at approximately 54% and 51%, respectively. The 2018 3RP appeal seeks $5.6 billion, and the 2018 HRP appeal for Syria seeks $3.5 billion.96 As of August 2018, the two 2018 appeals were funded at 38% and 39%, respectively.97

U.S. Policy

Since 2011, U.S. policy toward the unrest and conflict in Syria has attempted to pursue parallel interests and manage interconnected challenges, with varying degrees of success. Among the objectives identified by successive Administrations and by many Members in successive sessions of Congress have been:

- supporting Syrian-led efforts to demand more representative, accountable, and effective governance;

- seeking a negotiated settlement that includes a transition in Syria away from the leadership of Bashar al Asad and his supporters;

- limiting or preventing the use of military force by state and non-state actors against civilian populations;

- mitigating transnational threats posed by Syria-based Islamist extremist groups;

- meeting the humanitarian needs of internally and externally displaced Syrians;

- preventing the presence and needs of Syrian refugees from destabilizing neighboring countries;

- limiting the negative effects of other third party interventions on regional and international balances of power; and

- responding to and preventing the use of chemical weapons.

As Syria's conflict has changed over time from a situation of civil unrest and low intensity conflict to one of nationwide military conflict involving multiple internal and external actors, the policies, approaches, and priorities of the United States and others also have changed. As of August 2018, the United States and its Syrian and regional partners have not succeeded in inducing or compelling Syrian President Bashar al Asad to leave office or secured a fundamental reorientation of Syria's political system as part of a negotiated settlement process. The United States continues to advocate for an inclusive negotiated solution, but has largely acquiesced to Asad's re-assumption of political and security control. The unrestrained use of military force against civilian populated areas has been a consistent feature of the Syrian conflict since 2012, with violations of the law of armed conflict attributed by international observers to the Syrian government, several of its domestic opponents, and international actors such as Russia.

Transnational terrorist threats emanating from Syria have resulted in terrorist attacks in Europe and the Middle East, but appear to be more contained at present with the Islamic State's reign of terror over much of northeastern Syria and northwestern Iraq having come to an end. The United States remains the leading donor to ongoing international humanitarian relief efforts to assist millions of internally and externally displaced Syrians as well as the communities that struggle to support them in neighboring countries. Forceful interventions in Syria by Russia, Iran, Turkey, the United States, and Israel are creating a fundamentally different set of calculations for policymakers to consider relative to those that prevailed prior to the conflict. Similarly, the use of chemical weapons by the Syrian government in the conflict and the U.S. and international responses to that use have reshaped international norms and mechanisms for responding to chemical weapons threats.

Trump Administration Syria Policy

The Trump Administration's Syria policy initially reflected modified continuation of the Obama Administration's post-2015 approach, which prioritized counterterrorism efforts against the Islamic State and relied on U.S.-armed and trained local partners to regain and hold territory occupied by the group. The Trump Administration's approach may be broadly characterized as having intensified offensive military operations against Islamic State forces and as having shifted overall U.S. policy toward favoring a de-escalation of the wider conflict, even if such an outcome would result in a de facto victory for the Asad government.

In 2018, the Administration's policy was subject to an internal senior level review process, and the future extent and nature of U.S. military activities and the content and scope of U.S. assistance programs are uncertain. In April 2018, President Trump stated that U.S. troops would soon be withdrawn from Syria, in contrast with prior statements by U.S. diplomats and military officials and with the Administration's FY2019 appropriations requests.98 In January 2018, then-Secretary of State Rex Tillerson had laid out a U.S. policy approach for Syria that emphasized that the United States would provide stabilization assistance and "maintain a military presence in Syria focused on ensuring ISIS cannot re-emerge."99 Similarly, in a February 2018 hearing, CENTCOM Commander General Votel stated,

[...] after we have removed [ISIS] from their control of the terrain, we have to consolidate our gains and we have to ensure that the right security and stability is in place so that they cannot resurge. So that is—that is part of being responsible coalition members in here, and that will take some time, beyond all of this.100

In other public statements, military officials have minimized any divisions within the Administration regarding the future of U.S. military personnel in Syria and have described a conditions-based approach to determining the appropriate level of U.S. presence and activity. When asked to clarify the Administration's Syria policy in light of the President's call for a rapid U.S. exit from Syria, U.S. military officials stated that the President had not set a specific timeline for withdrawal.101 In July, Secretary Mattis stated that U.S. military forces were focused on the "last bastions" of the Islamic State in Syria, adding,

As that falls, then we'll sort out a new situation. But what you don't do is simply walk away and -- and leave the place as devastated as it is, based on this war. You don't just leave it, and then ISIS comes back. So that will involve immediate restoration of drinking water, for example, clearing IEDs and those kind of things […] My job is to destroy ISIS and to make certain, what we put in place, then -- local security force, train them up so ISIS can't get back in. 102

When asked whether coalition personnel would remain in Syria following the completion of the current and final stage of Operation Roundup, U.K. Army Major General Felix Gedney, Deputy Commander for Strategy and Support for CJTF-OIR stated,

…of course Operation Roundup will only mean the liberation is complete east of the Euphrates River. After liberation, we have to ensure the security of the areas that have been liberated and then that allows stabilization effort to take place, and only after that stabilization has taken place will we have ensured a lasting defeat of ISIS.103

In August, senior State Department officials stated further that "We're remaining in Syria. The focus is the enduring defeat of ISIS," and, that, "There should be no doubt as to the position of the President with respect to the broader issue of the U.S. enduring presence in Syria. We're there for the defeat, the enduring defeat of ISIS."104

As discussed below, defense appropriations requests for FY2019 envision ongoing U.S. investments in multi-year efforts to train and equip local forces to hold and secure territory recaptured from the Islamic State. General Gedney also noted that coalition forces would play a key role in providing security for civilian agencies leading stabilization efforts.

Some Administration officials have noted that threats emanating from Syria go beyond those posed by the Islamic State. General Votel has stated that groups based in Syria's northwestern province of Idlib "potentially pose long-term challenges for security of the region, above and beyond Syria."105 Nevertheless, in 2018 the Administration moved to end a range of programs in northwestern Syria, including in Idlib province. Funds reportedly are being redirected to stabilization efforts in northeastern Syria.106

In August 2018, the State Department announced the appointment of former U.S. ambassador to Iraq James Jeffrey as Special Representative for Syria Engagement.107 Jeffrey is to coordinate the Department's efforts on all areas of the Syria conflict—including terrorism, refugee issues, and political negotiations between government and opposition representatives at Geneva. The Syria components of the counter-ISIS campaign are to remain under the purview of Special Presidential Envoy for the Global Coalition to Defeat ISIS, Brett McGurk.

Potential Cooperation with Russia

Russia's 2015 military intervention on behalf of the Asad government created immediate military operational and technical challenges for U.S. forces operating in Syria. It also has generated a series of evolving strategic challenges and questions for U.S. policymakers.

Military Deconfliction

In late 2015, the United States established air safety protocols with Russia to de-conflict air operations over Syria and avoid confrontations or incidents that could provoke a broader bilateral crisis. In 2017, U.S. and Russian ground forces in Syria began to operate in close proximity to one another as part of operations to defeat the Islamic State, requiring additional de-confliction measures for ground movements. This formed what U.S. military officials described as "two nodes for de-confliction with the Russians," one for the U.S. air component of the counter-IS campaign (based at Al Udeid Air Base in Qatar) and one for the ground component (at CJTF-OIR headquarters at Camp Arifjan in Kuwait).108 In 2018, Secretary Mattis referenced an additional line of communication between the Joint Staff J5 (Strategic Plans and Policy) and the Russian General Staff in Moscow.109 Secretary Mattis has also emphasized that, "…in regard to Syria, what we do with the Russian Federation is we deconflict our operations. We do not coordinate them."110

U.S. military officials have described de-confliction measures with Russia as generally successful. Nevertheless, clashes between U.S. and pro-Syrian government forces in February 2018 reportedly killed 200-300 pro-government forces, many of them Russian nationals.111 U.S. military officials stated that U.S. strikes were conducted in self-defense following an "unprovoked attack" against SDF headquarters near Khusham, east of the provincial capital of Deir ez Zor. A statement released by CENTCOM stated that coalition service-members in an "advise, assist, and accompany" capacity were co-located with the SDF during the attack, which occurred 8 kilometers east of the Euphrates River de-confliction line.112 Secretary Mattis testified that, "The Russian high command in Syria assured us it was not their people. And my direction to the chairman was -- for the force, then, was to be annihilated. And it was."113

In response to questions about Russian fatalities, Russian officials have stated that no members of the Russian armed forces were killed, and suggested that any Russian mercenaries killed in the attack had not coordinated their activities with Moscow. A statement released by the Russian Defense Ministry noted that a pro-government militia unit conducting "surveillance and research activities" had come under coalition attack because it had failed to inform a Russian operational group of its plans to operate in the area.114

Syria at the Trump-Putin Helsinki Summit

On July 16, 2018, President Trump and Russian President Vladimir Putin held a summit in Helsinki, Finland, which they characterized as a first step towards improving bilateral relations. Neither the White House nor the Russian administration has released a formal readout of the summit, but both leaders indicated that Syria was among the topics discussed.

At a joint press conference following the summit, President Putin suggested that "the task of establishing peace and reconciliation" in Syria could be an area for successful U.S.-Russian cooperation, and added that the two countries might also cooperate on refugee return.115 Putin also expressed support for the Syrian regime's military campaign in southwest Syria—an area that Russia, the United States, and Jordan had delineated in 2017 as a de-escalation zone. Putin indicated that Russia expected southern Syria to return to the prewar status quo governed by the 1974 Israel-Syria Disengagement Agreement, which provides for separation of Syrian and Israeli forces around the Golan Heights. Putin also referenced UNSCR 338 (1973), which calls for a ceasefire as well as for the implementation of UNSCR 242 (1967). UNSCR 242 calls for Israel's withdrawal from territories occupied in 1967. Speaking at the same press conference, President Trump made fewer specific references to Syria but noted the importance of assisting the "people of Syria … on a humanitarian basis" and "creating safety for Israel." In reference to Russia, President Trump stated, "…our militaries do get along very well, and they do coordinate in Syria and other places."

In the weeks following the summit, U.S. officials minimized the impact of the summit on U.S. policy. Secretary Mattis stated that "there have been no policy changes."116 U.S. officials also emphasized that any cooperation with Russia on political and humanitarian issues in Syria should occur within the existing framework of the Geneva process (which includes Russia, but not Iran, and which the United States insists should follow the roadmap outlined in UNSCR 2254). In a response to a question on the potential for U.S.-Russia cooperation on refugee return—as suggested by President Putin—Secretary Mattis stated, "What we're trying to do [in] Syria is to get this to the Geneva process."117 Secretary Pompeo on July 25 also stated that refugee return "should happen through the political process in Geneva."118

|