Introduction

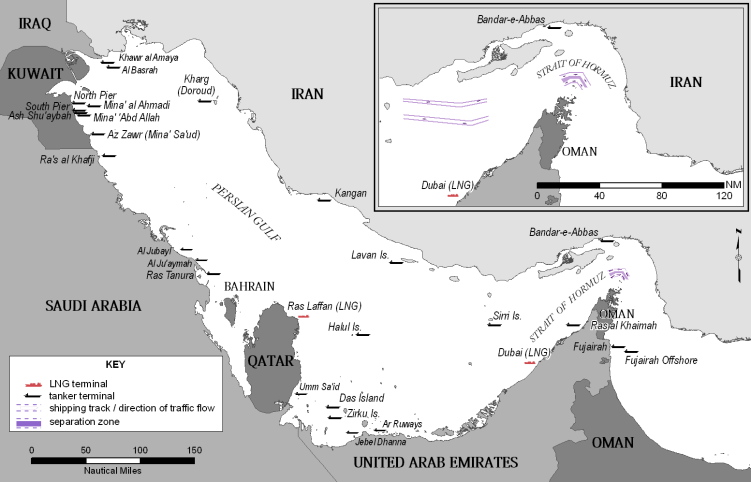

The exchanges of threats between members of the governments of Iran and the United States, including the presidents of both countries, have again raised the specter of an interruption of shipping through the Strait of Hormuz (the Strait), a key waterway for the transit of oil and natural gas to world markets. In the first half of 2018, approximately 18 million barrels per day (bpd) of crude oil and condensate, almost 4 million bpd of petroleum products, and over 300 million cubic meters per day in liquefied natural gas (LNG) exited the Strait. Iran accounted for about 10% of oil and 0% of the natural gas through the Strait. In a speech on July 22, Iranian President Rouhani stated, "We are the…guarantor of security of the waterway of the region throughout the history. Don't play with the lion's tail; you will regret it."1 (Western reporting took the reference to the waterway to mean the Strait of Hormuz, which is the narrow waterway that forms the entrance to the Persian Gulf from the Gulf of Oman and ultimately the Arabian Sea. See Figure 1). To which President Trump tweeted, "NEVER, EVER, THREATEN THE UNITED STATES AGAIN OR YOU WILL SUFFER CONSEQUENCES THE LIKES OF WHICH FEW THROUGHOUT HISTORY HAVE EVER SUFFERED BEFORE…"2 Earlier, on July 3, President Rouhani stated, "The Americans have claimed they want to completely stop Iran's oil exports. They don't understand the meaning of this statement, because it has no meaning for Iranian oil not to be exported, while the region's oil is exported."3

This is not the first time Iran's leaders have threatened to close or hinder shipping through the Strait of Hormuz. Prior to sanctions targeting Iran's oil exports in 2011/12, Iranian leaders threatened to close the Strait of Hormuz.4 Press reports that Iran is about to begin a large naval exercise in and around the Strait in early August 2018 is likely to inflame tensions further.

Congressional Interest

With the U.S. withdrawal from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) on May 8, 2018, there may be increased potential for Congress to consider legislation regarding sanctions on Iran. A number of bills, mostly prior to the May 8 withdrawal, have been introduced in the 115th Congress targeting aspects of Iran's leadership, military, and economy.

The Strait of Hormuz

The Strait of Hormuz is the narrow waterway that forms the entrance to the Persian Gulf from the Gulf of Oman and ultimately the Arabian Sea. At its narrowest point it is 22 nautical miles wide and falls within Iranian and Omani territorial waters. There are two shipping lanes through the Strait, one in each direction. Each is two miles wide and they are separated by a two-mile buffer.

|

|

Source: Jacqueline Nolan, Library of Congress, with data from Petroleum Economist, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, and Central Intelligence Agency. Note: Location of terminal icons are indicative and not a precise location. |

The United States and Sanctions5

On May 8, 2018, President Trump announced that the United States would no longer participate in the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) and that all U.S. secondary sanctions suspended to implement the JCPOA would be reinstated after a maximum "wind-down period" of 180 days (November 4, 2018). The U.S. sanctions that are going back into effect target all of Iran's core economic sectors. The Administration has indicated it will not look favorably on requests by foreign governments or companies for exemptions to allow them to avoid penalties for continuing to do business with Iran after that time.6

It remains uncertain whether reinstated U.S. sanctions based on the U.S. unilateral exit from the JCPOA will damage Iran's economy to the extent sanctions did during 2012-2015, when the global community was aligned in pressuring Iran. During that timeframe, Iran's economy shrank by 9% per year, crude oil exports fell from about 2.5 million bpd to about 1.1 million bpd, and Iran could not repatriate more than $120 billion in Iranian reserves held in banks abroad. JCPOA sanctions relief enabled Iran to increase its oil exports to nearly pre-sanctions levels, regain access to foreign exchange reserve funds and reintegrate into the international financial system, achieve about 7% yearly economic growth, attract foreign investments in key sectors, and buy new passenger aircraft. The sanctions relief reportedly contributed to Iranian President Hassan Rouhani's reelection in the May 19, 2017, vote. Yet, perceived economic grievances still sparked protests in Iran from December 2017 to January 2018.

The announced resumption of U.S. secondary sanctions has begun to harm Iran's economy because numerous major companies have announced decisions to exit the Iranian market rather than risk being penalized by the United States.7 As an indicator of the effects, the value of Iran's currency sharply declined in June 2018, and some economic-based domestic unrest flared in concert. Smaller demonstrations and unrest have simmered since. If the European Union and other countries are unwilling or unable to keep at least the bulk of the economic benefits of the JCPOA flowing to Iran, there is substantial potential for Iranian leaders to decide to cease participating in the JCPOA.

Iran's Perspective

Threats of U.S. sanctions that could reduce Iran's oil export earnings is a key impetus to Iran's threats to close the Strait of Hormuz. Historically, United Nations and multilateral sanctions had sought to reduce Iran's ability to develop its nuclear program by undermining its ability to develop its energy sector—targeting investment and financial linkages—but not directly targeting Iran's ability to export oil.8 This changed in 2012.

Due to its own dependence on commerce through the Strait, Iran may be unlikely to attempt to close the waterway, but rather to shape the international debate on Iran policy. Oil exports are vital to the Iranian government's fiscal health and the Iranian economy as a whole. Iran relies on the Strait not only for its oil exports, averaging about 2.2 million bpd in the first half of 2018, but also for the imports of some needed food and medical products. Iran could attempt to re-route imports through ports outside the Strait, such as Jask, or via established overland trade routes through Pakistan or Iraq. In 2016, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) estimated Iran's oil exports account for between 50% and 60% of total exports and almost 15% of GDP.9 The latter shows that Iran has a relatively diversified economy. However, many experts see Iran's warnings regarding the Strait of Hormuz as a reiteration of its long-held position to defend its oil exports. This implies that the likelihood that Iran might attempt to close the Strait increases if a broad embargo on purchases of Iran's oil emerges, either from countries complying with U.S. secondary sanctions or reinstating their own.

By threatening traffic through the Straits, Iran may risk alienating other nations, including its neighbors and customers, almost all of whom opposed the U.S. exit from the JCPOA and still want to engage economically with Iran. Most of the oil from the Persian Gulf, including from Iran, goes to Asian nations, with India and China being Iran's largest oil customers. Within weeks of the United States withdrawing from the JCPOA and stating its intention to reimpose sanctions, India's Foreign Minister Sushma Swaraj was quoted saying, "India follows only U.N. sanctions, and not unilateral sanctions by any country."10 China has also indicated that it may not comply with the U.S. request to halt all imports from Iran.11 Turkey, Iran's fourth largest oil importer, reportedly told U.S. officials it will not comply, as well.12

Iranian Options Regarding the Strait

Outright Closure. An outright closure of the Strait of Hormuz, a major artery of the global oil market, would be an unprecedented disruption of global oil supply and would likely contribute to higher global oil prices. However, at present, experts assess this to be a low probability event. Moreover, were this to occur, it is not likely to be prolonged. U.S. Secretary of Defense James Mattis asserted on July 27 that Iran's doing so would trigger a military response from the United States and others to preserve the freedom of navigation in that waterway.13 The U.S. response could reach beyond simply reestablishing Strait transit.

Harassment and/or Infrastructure Damage. Iran could harass tanker traffic through the Strait through a range of measures without necessarily shutting down all traffic. This took place during the Iran-Iraq war in the 1980s. Also, critical energy production and export infrastructure could be damaged as a result of military action by Iran, the United States, or other actors. Harassment or infrastructure damage could contribute to lower exports of oil from the Persian Gulf, greater uncertainty around oil supply, higher shipping costs, and consequently higher oil prices. However, harassment also runs the risk of triggering a military response and alienating Iran's remaining oil customers.

Continued Threats. Iranian officials could continue to make threatening statements without taking action. Alternately, Iran could conduct naval exercises in the waterway that raise tensions, whether or not any offensive action is planned. Cable News Network reported that the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) Navy, which is responsible for Iran's defense of the Strait, plans a naval exercise in the Strait in early August, involving dozens of Iran's small boats.14 The statements and maneuvers could still raise energy market tensions and contribute to higher oil prices, though only to the degree that oil market participants take such threats seriously.

Oil and Natural Gas Market Considerations

The Strait of Hormuz is a key route of the global oil market. Persian Gulf oil exporters—Iraq, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), and Qatar—shipped almost 22 million bpd of oil and products through the Strait in the first half of 2018, which is roughly 24% of the global oil market.15 On average, 33 oil and LNGs tankers exited the Persian Gulf through the Strait each day with most of the crude oil and natural gas going to Asian countries, including China, Japan, India, and South Korea. According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA), the United States imported 1.7 million bpd of crude oil from Persian Gulf countries in 2017, less than 10% of U.S. consumption and no natural gas. Separately, about 28% of the world's liquefied natural gas (LNG) trade, equal to about 3% of global natural gas consumption, moves through the Strait each year.16 This primarily entails exports from Qatar to Europe and Asia.

The Persian Gulf is also home to the world's spare oil production capacity. Some members of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), primarily Saudi Arabia, hold spare capacity as a result of their market management strategy. Kuwait and the United Arab Emirates hold small amounts of spare capacity as well. Spare capacity is viewed as a cushion to the oil market which can be used to offset supply disruptions. However, given its location, this spare capacity might not be available to offset a disruption to the Strait of Hormuz.

There are alternative oil pipeline routes to bypass the Strait, but not enough to account for all the oil that transits the Strait. According to EIA, there are three pipelines that transport oil from Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates that go around the Strait—East-West Pipeline and Abqaiq-Yanbu Natural Gas Liquids Pipeline from Saudi Arabia, and the Abu Dhabi Crude Oil Pipeline from the UAE. As of 2016, when EIA last reported on these pipelines, the East-West Pipeline and the Abu Dhabi Crude Oil Pipeline could take additional volumes of oil, approximately 2.9 million bpd and 1.0 million bpd, respectively. This would leave approximately 18 million bpd stranded should the Strait of Hormuz be closed.

A disruption of oil through the Strait of Hormuz could significantly affect global oil prices. Though most of the oil that flows through the Strait goes to Asia, the oil market is globally integrated and a disruption anywhere can contribute to higher oil prices everywhere. For example, a disruption of oil exported from the Persian Gulf to Asia would leave Asian refineries bidding for oil from alternative sources. While actual disruptions and perceived disruption risks in the past have contributed to prices being higher than they might have otherwise been, actual Iran-related events since 1980 have not necessarily resulted in clear and significant price increases ex-post (see able 1). Additionally, oil prices tend to quickly experience large price movements when supply deficits are in the 1.5 million bpd and 2 million bpd range. A supply deficit of 18 million bpd to 22 million bpd, an amount the market has never had to deal with, would likely result in significant upward pressure on prices. The numerous variables affecting the price of oil at any given time can make it difficult to estimate what specific change in price is due to a specific event. Nonetheless, reductions or threatened reductions to supply do tend to push oil prices up.

Key uncertainties for the impact of a disruption include how much global oil supply was reduced, risks of further reductions, and duration of the disruption. Risk of damage to oil production and export facilities in the Persian Gulf would also be of concern. Given limited bypass options, outright closure of the Strait would represent an unprecedented disruption to global oil supply and would likely cause a substantial increase in oil prices. However, as suggested above, outright closure may be unlikely, and even if it occurred, might not persist for very long.

In the event of a disruption, consumer countries would likely release strategic stocks to offset the impact on oil supply. As of May 2018, the United States held 660 million barrels of crude oil in the Strategic Petroleum Reserve (SPR),17 a government held stockpile of crude oil to be used to offset supply disruptions.18 The United States coordinates use of its SPR with other members of the International Energy Agency (IEA), which include Japan, Germany, South Korea, and other members of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). Some non-IEA countries, such as China, also hold strategic stocks, and may or may not coordinate with an IEA member release. Oil importing members of the IEA have an obligation to hold oil stocks equal to at least 90 days-worth of net imports. As of April 2018, IEA member countries held about 4.4 billion barrels of crude oil and refined products in inventory, of which 1.6 billion are held by governments.19 If drawn down at the maximum rate technically possible, these government-held stocks could be delivered to the market at an average rate of 10.4 million bpd of crude oil and 4 million bpd of products in the first month of an IEA collective action, diminishing thereafter.20 (The rate diminishes as stocks are depleted.) By offsetting the loss of supply, a strategic stock release could blunt the impact a disruption can have on oil prices.

|

Event |

Price Changes |

Commentary |

|

|

Prior Month |

Next Month |

||

|

Start of Iran/Iraq War, 9/23/1980a |

0.1% |

0.5% |

The monthly oil price did not change much prior to this conflict beginning and even a month into it. However, six months into the conflict oil prices were up 11%. |

|

"Tanker War" begins, 3/27/1984 |

-0.2% |

-0.9% |

The "tanker war" included 44 attacks against tankers from other nations over the course of nine months. During this time, prices remained close to the March 27 price or lower, dropping 14% by the end of the period. The large drop is more reflective of the global oil market than the uncertainty created by the tanker war. Supply levels remained high during the time period, while demand was growing slowly.b |

|

Re-flagged Bridgeton hits a mine (Operation Earnest Will), 7/24/1987 |

-1.6% |

-1.1% |

The Bridgeton, carrying the U.S. flag, hit a mine in the Persian Gulf. Under U.S. Operation Earnest Will, Kuwaiti tankers were re-flagged with the U.S. flag so that the U.S. Navy could protect them in the Persian Gulf. Prices stayed above the July 24th price for almost three weeks before steadily declining. As minimal oil was interrupted overall, the risk to supply was decreased consequently putting downward pressure on prices.c |

|

Operation Praying Mantis, 4/18/1988 |

10.7% |

-4.6% |

The U.S. operation destroyed almost 40% of Iran's navy. Prices after the event dropped immediately, with the biggest daily drop almost 5% two weeks later. Praying Mantis greatly diminished Iran's capabilities in the Persian Gulf, decreasing the likelihood of an oil cutoff. Leading up to U.S. Operation Praying Mantis, the overall oil market faced lower demand because of warm weather in Europe, and higher production as Saudi Arabia was producing at its OPEC quota and no longer below it and non-OPEC production was higher.d |

|

Iran arms Strait of Hormuz, 3/28/1995 |

2.5% |

4.9% |

The Pentagon announced that it was monitoring Iranian installation of missiles in the Strait of Hormuz. Iran also took possession and fortified two nearby islands claimed by them and the United Arab Emirates. During the month after the announcement daily prices fluctuated up and down before jumping at the end of the period. However, about a week after the event began prices declined for eight consecutive days. |

|

Iran threatens the Strait, 12/28/2011 |

1.0% |

0.2% |

Iran's first Vice President Mohammad Reza Rahimi was the first to threaten closure of the Strait. Prices initially rose almost daily from this event, peaking on January 4, 2012, almost 4% higher before declining. |

|

United States withdraws from JCPOA, 5/8/2018 |

3.5% |

-0.9% |

The oil market appears to have accounted for the U.S. withdrawal from the JCPOA with a price rise prior to the event. The addition of other market events also put upward pressure on prices. However, since the announcement on May 8, prices have fallen, indicating the market has adjusted to the new circumstances. |

Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration, Annual Oil Market Chronology, http://www.eia.gov/emeu/cabs/AOMC/8089.html.

Notes: Crude prices are NYMEX West Texas Intermediate crude prices (daily) except 1980, which is refiners acquisition cost of crude reported by EIA (monthly). A negative Prior Month price indicates that average 30-day price prior to the action data was greater than the price on the action date and therefore negative. A negative Next Month price means that the price on the action date was greater than the average 30-day price.

a. Although there were events leading up to September 23, 1980, that contributed to hostilities, this date is used as a start date to the military conflict.

b. U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA), Short-Term Energy Outlook, DOE/EIA-0202(84/3Q), Washington, DC, August 1984, p. 12, http://www.eia.gov/forecasts/steo/archives/3Q84.pdf.

c. EIA, Short-Term Energy Outlook, DOE/EIA-0202(87/4Q), Washington, DC, October 1987, p. 9, http://www.eia.gov/forecasts/steo/archives/4Q87.pdf.

d. EIA, Short-Term Energy Outlook, DOE/EIA-0202(88/2Q), Washington, DC, April 1988, p. 7, http://www.eia.gov/forecasts/steo/archives/2Q88.pdf.