Background

Since at least the 18th century, governments, industry, philanthropic organizations, and other nongovernmental organizations throughout the world have offered prizes as a way to reward accomplishments in science and technology (S&T). Napoleon's government offered a 12,000 franc prize (worth more than four years of a French captain's pay in 1803) for a technology that would enhance the preservation of food and help the government feed advancing military troops. In 1809, the prize was awarded to Nicolas François Appert, whose method of heating, boiling, and sealing food in airtight jars was published as a condition of the reward and serves as the basis for the modern process of canning foods. In 1919, businessman Raymond Orteig offered $25,000 (more than $375,000 today) for the first nonstop flight between New York and Paris. Charles Lindbergh, in the Spirit of St. Louis, won the prize in 1927. The success of the Orteig Prize in advancing commercial aviation is cited as inspiring the Ansari X-Prize1 more than 70 years later to lower the risk and cost of commercial space travel.2

Prizes generally fall into two main categories: innovation inducement prizes, which are designed to encourage the achievement of scientific and technical goals not yet reached, and recognition prizes such as the National Medal of Science, National Medal of Technology and Innovation, or the Nobel prizes, which reward past S&T accomplishments and do not have a specific scientific or technical goal. The prize competitions and legislation discussed in this report refer to innovation inducement prizes.

According to some experts, prize competitions should be viewed as "a potential complement to, and not a substitute for, the primary instruments of direct federal support of research and innovation—peer-reviewed grants and procurement contracts."3 Furthermore, prizes are not always considered to be the most appropriate mechanism to address all research and innovation objectives; for example, a 2014 report by the U.S. Chamber of Commerce Foundation specifically states that prizes are not a substitute for long-term basic research.4

The comparative strengths of prize competitions in relation to the use of federal grants and contracts, as described by the National Academy of Sciences in a 1999 report, include (1) the ability to attract a broader spectrum of participants and ideas by reducing costs and bureaucratic barriers to participation; (2) the potential leveraging of a sponsor's financial resources; (3) the ability of federal agencies to shift the technical and other risks to contestants; and (4) the capacity to educate, inspire, and potentially mobilize the public around scientific, technical, and societal objectives.5

Similarly, during the Obama Administration, the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) and the Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) described prize competitions as having the benefit of allowing the federal government to

- pay only for success and identify novel approaches, without bearing high levels of risk;

- establish ambitious goals without having to predict which team or approach is most likely to succeed;

- increase the number and diversity of individuals, organizations, and teams tackling a problem, including nonscientists and individuals who have not previously received federal funding;

- increase cost effectiveness, stimulate private-sector investment, and maximize the return on taxpayer dollars;

- further a federal agency's mission while motivating and inspiring others and capturing the public imagination; and

- establish clear success metrics and validation protocols that themselves become defining tools and standards for the subject, industry, or field.6

Some experts have indicated that while prize competitions have more uncertainty in terms of program outputs and outcomes than more traditional instruments (i.e., grants and contracts), the potential payoffs to federal agencies can be higher if properly designed and implemented.7 Specifically, determining the correct size of the cash prize; transparent, simple, and unbiased contest rules; and the proper treatment of intellectual property rights are considered important aspects of a successful prize competition.8

Broad Prize Competition Authority

In 2010, Congress passed the America COMPETES Reauthorization Act of 2010 (P.L. 111-358) providing the head of a federal agency with the authority to carry out prize competitions "to stimulate innovation that has the potential to advance the mission of the respective agency."9 Specifically, P.L. 111-358 added Section 24 to the Stevenson-Wydler Technology Innovation Act of 1980 (15 U.S.C. §3719) defining what activities constitute a prize competition and detailing how a federal agency should address liability issues, intellectual property rights, the judging of a prize competition, and other topics.

In 2017, the American Innovation and Competitiveness Act (P.L. 114-329) made a number of technical and clarifying amendments to this broad prize competition authority, including language authorizing the head of a federal agency to request and accept funds for the design and administration of a prize competition or for the cash prize itself from other federal agencies, state and local governments, private-sector for-profit entities, and nonprofit entities. The general provisions of the law, as amended, are as follows:

- Prize competitions are defined as being one or more of the following: (1) a competition that rewards and spurs the development of a solution to a well-defined problem; (2) a competition that helps identify and promote a broad range of ideas and facilitates development of such ideas by third parties, especially in an area that may not otherwise receive attention; (3) competitions that encourage participants to change their behavior or develop new skills during and after the competition; and (4) any other competition the head of an agency considers appropriate to stimulate innovation and advance the agency's mission.

- Federal agencies must advertise a competition widely to encourage broad participation, including publishing a notice of the competition on a publicly accessible government website (e.g., http://www.challenge.gov/).10 The notice must describe the subject of the prize competition, rules for participating, the registration process, the amount of the prize purse, and how the winner will be selected.

- To be eligible to win a federal prize competition, an individual, participating singly or within in a group, must be a United States citizen or permanent resident, cannot be a federal employee acting within the scope of their employment, and must be registered and in compliance with all the requirements and rules of the prize competition. Similarly, to be eligible to win a federal prize competition, a private entity must be incorporated in and maintain a primary place of business within the United States and must be registered and in compliance with the requirements and rules of the prize competition.

- Federal agencies must require all participants to register, assume any and all risks, and waive claims against the government. Registered participants must also obtain liability insurance or demonstrate financial responsibility; however, an agency can waive the insurance requirement.

- The federal government cannot gain an interest in intellectual property developed by a participant without written consent of the participant.

- The head of a federal agency must appoint one or more judges using guidelines that are transparent and promote balance. Additionally, a judge cannot have a personal or financial conflict of interest with any of the registered participants.

- Funding for a prize competition, including the design and administration of a competition, may consist of federally appropriated funds and/or funds provided by a state or local government or a private-sector for-profit or nonprofit entity. A federal agency can solicit and accept funds from other federal agencies, state and local governments, private-sector for-profit entities, and nonprofit entities. A prize competition cannot be announced until all of the funds have been appropriated or committed in writing.

- Federal agencies can enter into an agreement with a private-sector for-profit or nonprofit entity or a state or local government agency to administer a federal prize competition.

- A prize in excess of $50 million cannot be offered unless 30 days have elapsed after written notice is provided to Congress. The head of a federal agency must approve any award of more than $1 million.

- The Director of the Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) must submit a biennial report to Congress detailing the use of the prize competition authority provided by P.L. 111-358.11

Agency Specific Prize Competition Authorities

Over the years, Congress has provided some federal agencies with additional explicit authority to conduct prize competitions. Federal agencies with specific prize competition authorities are as follows:

- Department of Defense (DOD): In 1999, Congress provided prize competition authority to the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency through the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2000 (P.L. 106-65).12 In 2006, the authority was extended to the military departments through the John Warner National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2007 (P.L. 109-364). Specifically, the authority states that the Secretary of Defense can award prizes "in basic, advanced, and applied research, technology development, and prototype development that have the potential for application to the performance of the military missions of the Department of Defense."

- Department of Energy (DOE): In 2005, through the Energy Policy Act of 2005 (P.L. 109-58), the Secretary of Energy was authorized to carry out a program "to award cash prizes in recognition of breakthrough achievements in research, development, demonstration, and commercial application that have the potential for application to the performance of the mission of the Department."13 P.L. 109-58 also authorized the Freedom Prize with the goal of advancing technologies that will reduce America's dependence on foreign oil. In 2007, through the Energy Independence and Security Act of 2007 (P.L. 110-140), Congress authorized DOE to conduct the Hydrogen Prize and the Bright Tomorrow Lighting Prize to stimulate innovation and advancement in hydrogen energy technologies and solid-state lighting products, respectively.14 In 2011, through P.L. 111-358, Congress authorized the Director of the Advanced Research Projects Agency-Energy to provide awards in the form of cash prizes, among other mechanisms.15

- National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA): In 2005, through the National Aeronautics and Space Administration Authorization Act of 2005 (P.L. 109-155), the Administrator of NASA was granted the authority to award cash prizes "to stimulate innovation in basic and applied research, technology development, and prototype demonstration that have the potential for application to the performance of the space and aeronautical activities of the Administration."16

- Department of Health and Human Services (HHS): In 2006, through the Pandemic and All-Hazards Preparedness Act (P.L. 109-417), the Secretary of HHS was authorized "to award contracts, grants, cooperative agreements, or enter into other transactions, such as prize payments" to promote innovation and research and development on biodefense medical countermeasures.17 In 2016, through the 21st Century Cures Act (P.L. 114-255), the Director of the National Institutes of Health was directed to support prize competitions that would realize significant advancements in biomedical science or improve health outcomes, especially as they relate to human diseases or conditions.18

- National Science Foundation (NSF): In 2007, the America COMPETES Act (P.L. 110-69) authorized NSF "to receive and use funds donated by others" for the specific purpose of creating prize competitions for basic research.19

- Department of Transportation (DOT): In 2012, through the Moving Ahead for Progress in the 21st Century Act (P.L. 112-141), the Secretary of Transportation was authorized to use up to 1% of the funds made available from the Highway Trust Fund for research and development to carry out a prize competition program "to stimulate innovation in basic and applied research and technology development that has the potential for application to the national transportation system."20

- Department of Commerce (DOC): In 2018, through the Consolidated Appropriations Act for Fiscal Year 2018 (P.L. 115-141), the Secretary of Commerce, subject to the availability of funds, was directed to conduct prize competitions that will accelerate the development and commercialization of technologies to improve spectrum efficiency.21

Prize Competition Trends

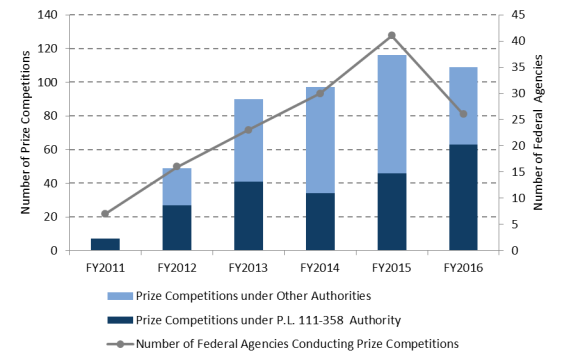

The use of prize competitions by federal agencies has grown since the enactment of the America COMPETES Reauthorization Act of 2010 (P.L. 111-358) and its inclusion of a broad prize competition authority as described above. As shown in Figure 1, the number of active prize competitions conducted under the authority provided in P.L. 111-358 grew from 7 in FY2011 to 63 in FY2016.22 The number of active prize competitions conducted under other authorities has also increased, peaking at 70 in FY2015.23 The number of federal agencies conducting active prize competitions has increased from 7 federal agencies in FY2011 to 26 in FY2016, with a high of 41 federal agencies conducting prize competitions in FY2015.

|

Figure 1. Number of Active Federal Prize Competitions, FY2011-FY2016 |

|

|

Source: Office of Science and Technology Policy, Implementation of Federal Prize Authority: Progress Report, Washington, DC, March 2012; Office of Science and Technology Policy, Implementation of Federal Prize Authority: Fiscal Year 2012 Progress Report, Washington, DC, December 2013; Office of Science and Technology Policy, Implementation of Federal Prize Authority: Fiscal Year 2013 Progress Report, Washington, DC, May 2014; Office of Science and Technology Policy, Implementation of Federal Prize Authority: Fiscal Year 2014 Progress Report, Washington, DC, April 2015; Office of Science and Technology Policy, Implementation of Federal Prize Authority: Fiscal Year 2015 Progress Report, Washington, DC, August 2016; and Office of Science and Technology Policy, Implementation of Federal Prize Authority: Fiscal Year 2016 Progress Report, Washington, DC, July 2017. Notes: Federal agencies conducting prize competition under authorities other than P.L. 111-358 are not required to report data on the use of prizes and therefore the data included in this figure for "Prize Competitions under Other Authorities" may be incomplete. |

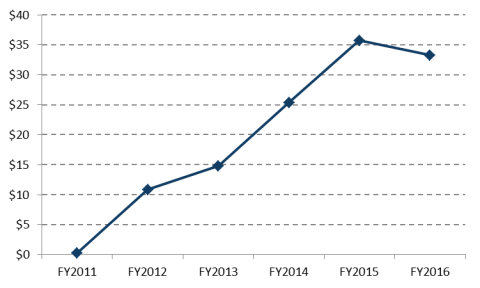

The total amount of prize money offered by federal agencies has also increased over time.24 In FY2011, the active prize competitions conducted by federal agencies under P.L. 111-358 offered a total of $247,000 and in FY2016 the total amount of prize money offered exceeded $30 million (Figure 2). The average value of the prize money offered by competitions under P.L. 111-358 increased from $35,286 in FY2011 to $527,947 in FY2016. However, an examination of the median amount of prize money offered per prize indicates that the size of federal prizes has remained relatively steady over time with a median value of $34,500 in FY2011 compared to $41,590 in FY2016.25

More than half of all prize competitions in FY2014-FY2016 were conducted in partnership with other federal agencies, nonprofit and for-profit private-sector entities, or others. According to OSTP, a clear distinction of the prize competitions that use the authority provided by P.L. 111-358 is "the broad partnerships that agencies are able to leverage." Specifically, in a 2017 report, OSTP found that 73% of the prize competitions conducted under P.L. 111-358 engaged in formal partnerships compared to 30% conducted under other authorities.26

Overall, the U.S. General Services Administration (GSA) estimates that since 2010 federal agencies have conducted more than 840 prize competitions and offered more than $280 million in prize money.27

|

Figure 2. Total Federal Prize Money Offered by Active Prize Competitions Conducted Under P.L. 111-358 in millions |

|

|

Source: Office of Science and Technology Policy, Implementation of Federal Prize Authority: Progress Report, Washington, DC, March 2012; Office of Science and Technology Policy, Implementation of Federal Prize Authority: Fiscal Year 2012 Progress Report, Washington, DC, December 2013; Office of Science and Technology Policy, Implementation of Federal Prize Authority: Fiscal Year 2013 Progress Report, Washington, DC, May 2014; Office of Science and Technology Policy, Implementation of Federal Prize Authority: Fiscal Year 2014 Progress Report, Washington, DC, April 2015; Office of Science and Technology Policy, Implementation of Federal Prize Authority: Fiscal Year 2015 Progress Report, Washington, DC, August 2016; and Office of Science and Technology Policy, Implementation of Federal Prize Authority: Fiscal Year 2016 Progress Report, Washington, DC, July 2017. Notes: Prize money offered may differ from the amount of prize money actually awarded. For example, in 2004 under the Grand Challenge, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency offered a prize of $1 million to a fully autonomous, unmanned ground vehicle capable of traveling 142 miles across desert terrain in the best time under 10 hours. None of the vehicles were able to complete the course and no prize money was awarded. |

Potential Policy Considerations

Federal agencies have increased the use of prize competitions to spur innovation and advance the mission of their respective agencies; however, there is limited information on the effectiveness and impact of prize competitions generally. According to experts, only a small number of prize competitions have been systematically evaluated.28 Members of Congress may conduct oversight through hearings (or other means) to gain insight into existing federal prize competitions and related programs to inform potential changes in the use of prizes by federal agencies. Questions for congressional consideration might include the following:

- Would the technology or innovation have been developed in the absence of a prize competition?

- Did the prize competition shorten the timeframe for the development of the technology or innovation?

- Was the prize competition cost effective?

- What, if any, other benefits were gained from conducting the prize competition?

- Would the use of a more traditional policy tool such as a grant or contract have resulted in the development of a similar technology or innovation?

- If the prize competition were designed differently, would a more effective or revolutionary technology or innovation have been developed?

- What are the appropriate metrics for determining the success of a prize competition? Are the metrics different when evaluating the near-term and long-term impacts of a prize competition?

- What are the best practices of successful prize competitions?

According to a 2017 report, "if measurement, assessment, and learning become standard parts of innovation challenges, the challenge community will have a growing evidence base with which to move ahead quickly in applying approaches best able to achieve funders' objectives, in terms of social impact and on other metrics."29 The awarding of a prize may be considered by some as evidence of the success of a prize competition; however, experts generally agree that both quantitative and qualitative information is necessary to assess success. Members of Congress may examine what metrics and other data and information federal agencies collect on federal prize competitions, including any effort by OSTP or others to standardize data collection across the federal government.

The design and implementation of a prize competition is held by many to be critical to the success of the competition. Specifically, in a 1999 report, the National Academy of Engineering stated that "if prize contests are not designed or administered with care, they may discourage prudent risk taking or unorthodox approaches to particular scientific or technological challenges, or scare away potential contestants with excessive bureaucracy."30

Increased interest in the use of prize competitions by Congress and the current and previous Administrations has resulted in federal agencies developing more in-house expertise in the design and administration of prize competitions. For example, in FY2016, 8 federal agencies had department-wide policy and guidance on the use of prize competitions; 5 agencies had dedicated, full-time prize competition personnel; 10 agencies enabled a distributed network of prize managers and points of contact; and 5 agencies were providing centralized training and design support to agency staff. Additionally, GSA fostered the development of a federal community of practice in prize competitions, and in 2016, published a prize and challenges toolkit to assist federal agencies.31 On the other hand, InnoCentive, a company that performs prize competition services for public and private organizations, has argued for increased outsourcing of the design and administration of publicly funded prize competitions, stating

Governments and international public institutions should be actively seeking to improve their own innovation systems expertise, but they should also support the development of a strong, vibrant, and bold innovation management industry in the private sector. Ultimately, it is this vibrant marketplace of independent organizations, with their global diversity of perspectives and ideas, that will best drive forward the evolution and progress of innovation using challenges.32

Members of Congress may examine the capability and expertise of federal agencies in the design and administration of prize competitions, in addition to federal agencies' use of partners and paid vendors to create teams with the ability and experience needed to run successful prize competitions.

In addition to examining current federal prize competitions and federal agency expertise, some Members of Congress may want to establish new federal prize competitions through legislation. In developing such legislation, policymakers may consider some of the following questions:33

- Should the legislation be general and flexible, providing federal agencies with an overview of the prize goals, or specific, detailing instructions to the agency regarding the prize competition? Such details may include timeframe, award amount, participant eligibility, administration, contest rule determination, competition judges, intellectual property rights, liability, and program evaluation.

- What should be the prize topic? Who should select it?

- What should be the goals of the program? What are the relative importance of technological advancement, education, and public awareness?

- Should there be a time limit for the prize?

- Should a monetary award be part of the prize? If so, how much? If not, is the publicity associated with winning the prize sufficient to encourage quality contestant participation?

- Should there be intermediary prizes (e.g., should partial prizes be awarded to participants that achieve certain milestones)?

- Who should be eligible to participate in the competition? For example, should employees of federal agencies or federally funded research and development centers (FFRDCs) be allowed to compete? If so, should they be able to use federal funds and facilities? Should foreign entities, such as non-U.S. citizens, corporations, or U.S. subsidiaries of foreign-owned corporations, be allowed to compete?

- Who should administer the program? For example, should a federal agency administer the program independently, do so in partnership with another federal agency or nonfederal organization, or act as a financial or nonfinancial partner in a competition administered by a nonfederal organization?

- Who should judge the competition? Should there be an appeal process?

- What are the criteria for the program to be considered successful?

Answering some of these questions may require the guidance and input of the science and technology community, federal agencies, and those experienced in the administration of prize competitions. The constantly changing state of the art of science and engineering due to new discoveries and innovation may lead observers to suggest providing flexibility in prize legislation.

Legislation in the 115th Congress

In the 115th Congress, as of the date of this report, more than 20 bills have been introduced to authorize or establish prize competitions within various federal agencies. See Table A-1 in the appendix for a list of the proposed legislation, a brief summary, and the most recent action.

Appendix. List of Federal Prize Competition Legislation

|

Bill Number |

Bill Title |

Summary |

Latest Action(s) |

|

Timber Innovation Act of 2017 |

Section 4 of the bill would direct the Department of Agriculture to carry out an annual competition for FY2017-FY2021 for a tall wood building design, or other innovative wood product demonstration. |

H.R. 1380 referred to the Subcommittee on Environment, House Committee on Science, Space, and Technology on 04/25/2017. S. 538 referred to Senate Committee on Agriculture, Nutrition, and Forestry on 03/07/2017. |

|

|

Improving Access to Affordable Prescription Drugs Act |

Section 301 of the bill would direct the Director of the National Institutes of Health to award up to three prizes for qualifying products that provide added benefit for patients over existing therapies in the treatment of serious and life-threatening bacterial infections. |

H.R. 1776 referred to the Subcommittee on Health, House Committee on Ways and Means on 04/05/2017. S. 771 referred to the Senate Committee on Finance on 03/29/2017. |

|

|

Coral Reef Sustainability Through Innovation Act of 2017 |

Would amend the Coral Reef Conservation Act to authorize the 12 federal agencies on the U.S. Coral Reef Task Force, which includes the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, to carry out, either individually or cooperatively, prize competitions that promote coral reef research and conservation. The prize competitions should be designed to help the United States achieve its goal of developing new and effective ways to advance the understanding, monitoring, and sustainability of coral reef ecosystems. |

H.R. 2203 referred to the Subcommittee on Environment, House Committee on Science, Space, and Technology on 05/22/2018. S. 958 referred to the Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation on 04/27/2017. |

|

|

To codify the Small Business Administration's Growth Accelerator Fund Competition, and for other purposes. |

Would amend the Small Business Act to codify provisions establishing the Growth Accelerator Fund Competition program, under which the Small Business Administration would award prizes competitively to covered entities (private entities that are incorporated in and maintain a primary place of business in the United States) that assist small business concerns in accessing capital, mentors, and networking opportunities; and advise small business concerns, including on market analysis, company strategy, revenue growth, and securing funding. |

Referred to the House Committee on Small Business on 05/25/2017. |

|

|

National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2018 |

Section 1089 of the bill would allow the Secretary of Defense to establish a prize competition designed to accelerate identification of the root cause or causes of, or find solutions to, physiological episodes experienced in Navy, Marine Corps, and Air Force training and operational aircraft. |

Became P.L. 115-91 on 12/12/2017. |

|

|

Methane Emissions Mitigation Act |

Section 4 of the bill would direct the Secretary of Energy to carry out a methane leak detection and mitigation technology demonstration prize competition. |

Referred to the Subcommittee on Energy, House Committee on Science, Space, and Technology on 05/22/2018. |

|

|

Ocean Acidification Innovation Act of 2017 |

Would amend the Federal Ocean Acidification Research and Monitoring Act of 2009 to authorize a federal agency with a representative serving on the Interagency Working Group on Ocean Acidification to carry out a program that competitively awards prizes for stimulating innovation to advance the nation's ability to understand, research, or monitor ocean acidification or its impacts or to develop management or adaptation options for responding to ocean acidification. |

Referred to the Subcommittee on Environment, House Committee on Science, Space, and Technology on 05/22/2018. |

|

|

Harmful Algal Blooms Solutions Act of 2017 |

Would direct the Secretary of Commerce to establish a program to award prizes to eligible persons for achievement in developing innovative, environmentally safe technologies and practices for reducing, mitigating, and controlling harmful algal blooms in one or more of the following categories: (1) large-scale physical removal of algal biomass; (2) removal of, or rendering harmless, harmful algal bloom toxins in the environment; (3) reduction of available nutrients that fuel harmful algal blooms; or (4) real-time monitoring of harmful algal blooms and early-warning systems. |

Referred to the Subcommittee on Environment, House Committee on Science, Space, and Technology on 05/22/2018. |

|

|

Carbon Capture Prize Act |

Would authorize the Secretary of Energy to establish a prize competition for the research, development, or commercialization of technology that would reduce the amount of carbon in the atmosphere, including by capturing or sequestering carbon dioxide or reducing the emission of carbon dioxide. |

Referred to the Subcommittee on Environment, House Committee on Science, Space, and Technology on 05/22/2018. |

|

|

Wildlife Innovation and Longevity Driver Act (WILD) Act |

Would direct the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to establish the Theodore Roosevelt Genius Prizes for (1) prevention of wildlife poaching and trafficking, (2) promotion of wildlife conservation, (3) management of invasive species, (4) protection of endangered species, and (5) nonlethal management of human-wildlife conflicts. |

H.R. 4489 referred to the Subcommittee on Environment, House Committee on Science, Space, and Technology on 05/22/2018. H.R. 5885 referred to the Subcommittee on Water, Power and Oceans, House Committee on Natural Resources 06/05/2018. S. 826 passed in the Senate on 06/08/2017. |

|

|

RAY BAUM'S Act of 2018 |

Section 715 of the bill would direct the Secretary of Commerce, subject to the availability of funds, to conduct prize competitions that will accelerate the development and commercialization of technologies to improve spectrum efficiency. (See also S. 19.) |

Passed in the House on 03/06/2018. |

|

|

Challenges and Prizes for Climate Act of 2018 |

Would direct the Secretary of Energy to carry out a prize competition program that includes at least one prize competition in each of the following areas: carbon capture and beneficial use, energy efficiency, energy storage, climate resiliency, and data analytics. |

Referred to the Subcommittee on Research and Technology, House Committee on Science, Space, and Technology on 05/22/2018. |

|

|

Fossil Energy Research and Development Act of 2018 |

Section 12 of the bill would direct the Secretary of Energy to carry out a prize competition for carbon dioxide capture from media in which the concentration of carbon dioxide is less than 1% by volume. |

Referred to the Subcommittee on Energy, House Committee on Science, Space, and Technology on 05/22/2018. |

|

|

Making Opportunities for Broadband Investment and Limiting Excessive and Needless Obstacles to Wireless Act |

Section 19 of the bill would direct the Secretary of Commerce, subject to the availability of funds, to conduct prize competitions that will accelerate the development and commercialization of technologies to improve spectrum efficiency. (See also H.R. 4986.) |

Passed in the Senate on 08/03/2017. Subsequently included in the Consolidated Appropriations Act for Fiscal Year 2018 (P.L. 115-141) enacted on 03/23/2018. |

|

|

Medical Innovation Prize Fund Act |

Would deny any person the exclusive right to manufacture, distribute, sell, or use a drug, a biological product, or a medication manufacturing process and establishes the Fund for Medical Innovation Prizes to provide for prize payments in lieu of market exclusivity. The Board of Trustees of the fund must award prize payments to (1) the first person to receive approval for a medication; (2) the holder of the patent for a manufacturing process; and (3) persons or communities that contributed to the development of a rewarded medication or process through the open, nondiscriminatory, and royalty-free sharing of knowledge, data, materials, and technology. |

Referred to the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions on 03/02/2017. |

|

|

Department of Defense Software Management Improvement Act of 2017 |

Would direct the Secretary of Defense to award a prize for identifying, capturing, and storing existing Department of Defense custom-developed computer software and related technical data and for improving, repurposing, or reusing software to better support the Department of Defense mission. |

Referred to the Senate Committee on Armed Service on 06/27/207. |

|

|

Energy and Natural Resources Act of 2017 |

Subtitle F of the bill would require the Secretary of Energy to establish an E-Prize Competition to reduce energy costs through increased efficiency, conservation, and technology innovation in high-cost regions and to create a Carbon Dioxide Capture Technology Prize for carbon dioxide capture from media in which the concentration of carbon dioxide is diluted (defined in the bill as "a concentration of less than one percent by volume"). |

Hearing held in Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources on 09/19/2017. |

|

|

Coastal Communities Adaptation Act |

Section 5 of the bill would authorize the Secretary of Commerce to award prizes to stimulate innovation in coastal risk reduction and resiliency measures. |

Referred to the Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation on 04/26/2018. |

Source: CRS analysis based on data from Congress.gov.