Background

The Appointments Clause of the Constitution generally requires high-level "officers of the United States" to be appointed through nomination by the President, with the advice and consent of the Senate.1 However, appointment to these advice and consent positions can be a lengthy process, and officers sometimes unexpectedly vacate offices, whether by resignation, death, or other absence, leaving before a successor has been chosen. In particular, there are often a large number of vacancies during a presidential transition, when a new President seeks to install new officers in important executive positions.2 The most recent transition of Administrations was no exception, and reports have noted that a number of offices across the executive branch currently remain vacant.3 In the case of such a vacancy, Congress has long provided that individuals who were not appointed to that office may temporarily perform the functions of that office.4

Generally, to serve as an acting officer for an advice and consent position, a government officer or employee must be authorized to perform the duties of a vacant office by the Federal Vacancies Reform Act of 1998 (Vacancies Act).5 The Vacancies Act allows only certain classes of employees to serve as an acting officer for an advice and consent position,6 and specifies that they may serve for only a limited period.7 If a covered acting officer's service is not authorized by the Vacancies Act, any attempt by that officer to perform a "function or duty" of a vacant office has "no force or effect."8

This report first describes how the Vacancies Act operates and outlines its scope, identifying when the Vacancies Act applies to a given office, how it is enforced, and which offices are exempt from its provisions. The report then explains who may serve as an acting officer and for how long, focusing on the limitations the Vacancies Act places on acting service. Finally, the report turns to issues of particular relevance to Congress, primarily highlighting the Vacancies Act's enforcement mechanisms.

Scope and Operation of the Vacancies Act

The Vacancies Act generally provides "the exclusive means for temporarily authorizing an acting official to perform the functions and duties of any office of an Executive agency . . . for which appointment is required to be made by the President, by and with the advice and consent of the Senate."9 The Vacancies Act's requirements are triggered if an officer serving in an advice and consent position in the executive branch "dies, resigns, or is otherwise unable to perform the functions and duties of the office."10

Because the Vacancies Act is generally exclusive and subject to limited exceptions,11 a person may not temporarily perform "the functions and duties" of a vacant advice and consent position unless that service comports with the Vacancies Act.12 The Vacancies Act specifies that a "function or duty" is one that, by statute or regulation, must be performed by the officer in question.13 Section 334814 provides that, "unless an officer or employee is performing the functions and duties [of an office] in accordance with" the Act,15 "the office shall remain vacant."16 If there is no acting officer serving in compliance with the Vacancies Act, then generally "only the head of [an agency] may perform" the functions and duties of that vacant office.17 As a result, Section 3348 usually allows three types of people to perform the functions and duties of an advice and consent office when it is vacant: the agency head, a person complying with the Vacancies Act, or a person complying with another statute that allows acting service.18

Section 3348 further provides that "an action taken by any person who" is not complying with the Vacancies Act "in the performance of any function or duty of a vacant office . . . shall have no force or effect."19 The Supreme Court has suggested that the Vacancies Act renders any noncompliant actions "void ab initio,"20 meaning that the action was "null from the beginning."21 The consequences that flow from a determination that an action is "void" are more severe than if a court were to announce that the action was merely "voidable."22 A "voidable" action is one that may be judged invalid because of some legal defect, but that "is not incurable."23 For instance, before a court strikes down a voidable agency decision, it will often inquire into whether the legal defect created actual prejudice.24 If an error is harmless, the court may uphold the agency action.25 Critically, acts that are "void" may not be ratified or rendered harmless, meaning that another person who properly exercises legal authority on behalf of an agency may not subsequently approve or replicate the act, thereby rendering it valid.26 The Vacancies Act affirms this consequence by explicitly specifying that an agency may not ratify any acts taken in violation of the statute.27

As is discussed in more detail later in this report,28 the Vacancies Act has primarily been enforced through the courts, when a person with standing challenges an agency action on the basis that it was undertaken by an officer who was performing a function or duty of a vacant office in violation of the Vacancies Act.29 If such a challenge is successful, a court would be likely to vacate the challenged agency action.30

Which Offices?

The Vacancies Act generally applies to advice and consent positions in executive agencies.31 The term "Executive agency"32 is defined broadly in Title 5 of the U.S. Code to mean "an Executive department, a Government corporation, [or] an independent establishment."33 However, the Vacancies Act explicitly excludes certain offices altogether.34 First, the Vacancies Act does not apply to officers of "the Government Accountability Office."35 Second, a distinct provision states that the Vacancies Act does not apply to (1) a member of a multimember board that "governs an independent establishment or Government corporation"; (2) a "commissioner of the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission"; (3) a "member of the Surface Transportation Board"; or (4) a federal judge serving in "a court constituted under article I of the United States Constitution."36

Additionally, while not excluded from the other requirements of the Vacancies Act,37 certain offices are exempt from the provision allowing only agency heads to perform the duties of a vacant office and the provision that renders noncompliant actions void.38 Specifically, Section 3348(e) states that "this section"—Section 3348—"shall not apply to"

(1) the General Counsel of the National Labor Relations Board;

(2) the General Counsel of the Federal Labor Relations Authority;

(3) any Inspector General appointed by the President, by and with the advice and consent of the Senate;

(4) any Chief Financial Officer appointed by the President, by and with the advice and consent of the Senate; or

(5) an office of an Executive agency (including the Executive Office of the President, and other than the Government Accountability Office) if a statutory provision expressly prohibits the head of the Executive agency from performing the functions and duties of such office.39

The legislative history of the Vacancies Act sheds some light on the purpose of this exemption, suggesting that Congress sought to exclude these "unusual positions" from Section 3348 because these officials are meant to be "independent" of the commission or agency in which they serve.40 The Senate report accompanying the Act suggests that Congress intended "to separate the official who would investigate and charge potential violations of the underlying regulatory statute from the officials who would determine whether that statute had actually been violated."41 Allowing the head of the agency—or the commissioners—to perform the nondelegable duties of these positions would undermine the independence of these positions.42

It is not entirely clear what the consequences are if an acting officer in one of these exempt positions violates the Vacancies Act. Because Section 3348 does not apply to those positions, it appears that any noncompliant actions should not be rendered void.43 Instead, a court might conclude that any noncompliant acts are merely voidable—or could conclude that even if these officers violate the Vacancies Act, that law will not invalidate their actions.44 In NLRB v. SW General, Inc., the Supreme Court held that the service of the Acting General Counsel of the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) violated the Vacancies Act, but noted that this position was exempt "from the general rule that actions taken in violation of the [Vacancies Act] are void ab initio."45 The Court affirmed the D.C. Circuit's ruling vacating the Acting General Counsel's noncompliant actions, but did not explicitly reconsider the issue of remedy.46

The D.C. Circuit in S.W. General, Inc. had itself clarified that it was not fully exploring the question of the appropriate remedy and was merely assuming, on the basis of the parties' arguments, "that section 3348(e)(1) renders the actions of an improperly serving Acting General Counsel voidable, not void."47 Because the D.C. Circuit assumed that the contested actions were voidable rather than void, the court considered but ultimately rejected two legal doctrines—the harmless error and de facto officer doctrine—that could have allowed the court to uphold the NLRB's action.48 If the Acting General Counsel were not exempt from Section 3348 and his noncompliance with the Vacancies Act had rendered his acts void ab initio, the court could not have considered whether any other legal doctrines cured the initial legal error with the Acting General Counsel's actions.49

Finally, the Vacancies Act contemplates that other statutes may, under limited circumstances, either supplement or supersede its provisions.50 Section 3347 provides that the Vacancies Act is exclusive unless "a statutory provision expressly" authorizes "an officer or employee to perform the functions and duties of a specified office temporarily in an acting capacity."51 However, Section 3347 states that a general statute authorizing the head of an executive agency "to delegate duties statutorily vested in that agency head to, or to reassign duties among, officers or employees of such Executive agency" will not supersede the limitations of the Vacancies Act on acting service.52 For instance, 28 U.S.C. § 510, which states generally that the Attorney General may authorize any other employee to perform any function of the Attorney General, likely would not render the Vacancies Act nonexclusive.53 To supplement or supersede the Vacancies Act, a statute must "expressly" authorize "acting" service.54 Under certain circumstances, it might be the case that more than one statute governs acting service in a given office,55 and that a person could lawfully serve as an acting officer under either statute.56

The Vacancies Act also makes certain exemptions for holdover provisions in other statutes: Section 3349b provides that the Vacancies Act "shall not be construed to affect any statute that authorizes a person to continue to serve in any office" after the expiration of that person's term.57

What Are the "Functions and Duties" of an Office?

The Vacancies Act limits an officer or employee's ability to perform "the functions and duties" of a vacant advice and consent office.58 For the purposes of the Vacancies Act, a "function or duty" must be (1) established either by statute or regulation and (2) "required" by that statute or regulation "to be performed by the applicable officer (and only that officer)."59 If the function or duty is established by regulation, that regulation must have been in effect "at any time during the 180-day period preceding the date on which the vacancy occurs."60 Thus, the Vacancies Act appears to apply only to functions or duties that a statute or regulation has exclusively assigned to a specific officer, generally referred to as the nondelegable functions and duties of a vacant office.61

Conversely, the Vacancies Act likely does not prevent another person from performing any duties of an office that are delegable. So long as a statute or regulation does not require a specific officer to perform certain functions and duties, an agency could theoretically delegate all of the tasks that had previously been performed by an officer in a now-vacant advice and consent position to another officer or employee.62 That other employee would likely be able to perform all of those delegable tasks without violating the Vacancies Act because the Act is seemingly only concerned with nondelegable functions and duties.63

There is, however, very little case law clarifying how to determine what "functions and duties" are within the scope of the Vacancies Act.64 One federal district court noted that the Vacancies Act covered only "the 'functions and duties' . . . that are required by statute or regulation to be performed exclusively by the official occupying that position," and consequently held that a person lawfully serving in another role in an agency could perform certain job duties of a vacant office because those duties had been validly delegated to that person.65 Courts might analyze this issue under the general legal principles that normally govern an inquiry into whether a particular duty is delegable.66

Vacancies Act Limitations on Acting Service

Section 3348 of the Vacancies Act allows only certain officers or employees to perform the "functions and duties" of a vacant advice and consent office.67 Unless an acting officer is serving in compliance with the Vacancies Act, only the agency head can perform a nondelegable duty of a vacant advice and consent office.68 The Vacancies Act creates two primary types of limitations on acting service: it limits (1) the classes of people who may serve as an acting officer,69 and (2) the time period for which they may serve.70

Who Can Serve as an Acting Officer?

Section 3345 allows three classes of government officials or employees to temporarily perform the functions and duties of a vacant advice and consent office under the Vacancies Act.71 First, as a default and automatic rule, once an office becomes vacant, "the first assistant to the office" becomes the acting officer.72 The term "first assistant" is a unique term of art under the Vacancies Act.73 Nonetheless, the term is not defined by the Act and its meaning is not entirely clear.74 For many offices, a statute or regulation explicitly designates an office to be the "first assistant" to that position.75 However, this is not true for all offices, and in those cases, who qualifies as the "first assistant" to that office may be open to debate.76

Alternatively, the President "may direct" two other classes of people to serve as an acting officer of an agency instead of the "first assistant."77 First, the President may direct a person currently serving in a different advice and consent position to serve as acting officer.78 Second, the President can select a senior "officer or employee" of the same executive agency, if that employee served in that agency for at least 90 days during the year preceding the vacancy and is paid at a rate equivalent to at least a GS-15 on the federal pay scale.79

Ability to Serve If Nominated to Office

Section 3345 places an additional limitation on the ability of these three classes of people to serve as acting officers for an advice and consent position. As a general rule, if the President nominates a person to the vacant position, that person "may not serve as an acting officer" for that position.80 Thus, if the President submits for nomination a person who is currently the acting officer for that position, that person usually may not continue to serve as acting officer without violating the Vacancies Act.81 The President can name another person to serve as an acting officer instead of the nominated person.82

The limitations of the Vacancies Act can create the need to shift government employees to different positions within the executive branch. For example, in January 2017, shortly after entering office, President Trump named Noel Francisco as Principal Deputy Solicitor General.83 Francisco then began to serve as Acting Solicitor General.84 In March, the President announced that he would be nominating Francisco to serve permanently as the Solicitor General.85 After this announcement, Francisco was moved to another role in the department and Jeffrey Wall, who was chosen by Francisco to be the new Principal Deputy Solicitor General, became the acting Solicitor General.86 This last shift may have been done to comply with the Vacancies Act.87 Ultimately, the Senate confirmed Francisco to the position of Solicitor General on September 19, 2017.88

There is an exception to this limitation: a person who is nominated to an office may serve as acting officer for that office if that person is in a "first assistant" position to that office and either (1) has served in that position for at least 90 days89 or (2) was appointed to that position through the advice and consent process.90 Returning to the example of the Solicitor General position, it appears that this exception would not have allowed Noel Francisco to continue to serve as the Acting Solicitor General, once nominated to that position.91 Although Francisco may have been in a first assistant position, as the Principal Deputy Solicitor General,92 he had not served in that position for 90 days, nor had he been appointed to that position through the advice and consent process.93

For How Long?

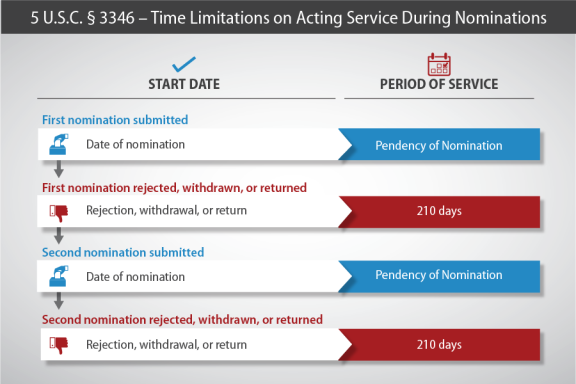

The Vacancies Act generally limits the amount of time that a vacant advice and consent position may be filled by an acting officer.94 Section 3346 provides that a person may serve "for no longer than 210 days beginning on the date the vacancy occurs," or, "once a first or second nomination for the office is submitted to the Senate, from the date of such nomination for the period that the nomination is pending in the Senate."95 These two periods run independently and concurrently.96 Consequently, the submission and pendency of a nomination allows an acting officer to serve beyond the initial 210-day period.97

|

|

Source: 5 U.S.C. § 3346. |

The 210-day time limitation is tied to the vacancy itself, rather than to any person serving in the office, and the period generally begins on the date that the vacancy occurs.98 This period does not begin on the date an acting officer is named, and because it runs continuously from the occurrence of the vacancy, the time limitation is unaffected by any changes in who is serving as acting officer.99 The period is extended during a presidential transition period when a new President takes office.100 If a vacancy exists on the new President's inauguration day or occurs within 60 days after the inauguration,101 then the 210-day period begins either 90 days after inauguration or 90 days after the date that the vacancy occurred, depending on which is later.102 If an acting officer attempts to perform a function or duty of an advice and consent office after the 210-day period has ended, and if the President has not nominated anyone to the office, that act will have no force or effect.103

Alternatively, Section 3346 allows an acting officer to serve while a nomination to that position "is pending in the Senate," regardless of how long that nomination is pending.104 The legislative history of the Vacancies Act suggests that an acting officer may serve during the pendency of a nomination even if that nomination is submitted after the 210-day period has run following the start of the vacancy.105 "If the first nomination for the office is rejected by the Senate, withdrawn, or returned to the President by the Senate," then an acting officer may continue to serve for another 210-day period beginning on the date of that rejection, withdrawal, or return.106 If the President submits a second nomination for the office, then an acting officer may continue to serve during the pendency of that nomination.107 If the second nomination is also "rejected, withdrawn, or returned," then an acting officer may continue for one last 210-day period.108 However, an acting officer may not serve beyond this final period—the Vacancies Act will not allow acting service during the pendency of a third nomination, or any subsequent nominations.109 Again, if the acting officer serves beyond the pendency of the first or second nomination and the subsequent 210-day periods, any action performing a function or duty of the office will have no force or effect.110

|

|

Source: 5 U.S.C. § 3346. |

Potential Considerations for Congress

Exclusivity of the Vacancies Act

The Vacancies Act provides "the exclusive means" to authorize "an acting official to perform the functions and duties" of a vacant office—unless another statute "expressly"

(A) authorizes the President, a court, or the head of an Executive department, to designate an officer or employee to perform the functions and duties of a specified office temporarily in an acting capacity; or

(B) designates an officer or employee to perform the functions and duties of a specified office temporarily in an acting capacity[.]111

Across the executive branch, there are many statutes that expressly address who will temporarily act for specified officials in the case of a vacancy in the office.112 In fact, the Senate report on the Vacancies Act expressly identified 40 agency-specific provisions that "would be retained by" the Act.113 To take one example, the Senate report anticipated that the Vacancies Act would not disturb the provision governing a vacancy in the office of the Attorney General.114 That statute provides that "[i]n case of a vacancy in the office of Attorney General, or of his absence or disability, the Deputy Attorney General may exercise all the duties of that office . . . ."115

In the event that there is an agency-specific statute designating a specific government official to serve as acting officer, the Vacancies Act will no longer be exclusive.116 But even if the Vacancies Act does not exclusively apply to a specific position, it will not necessarily be wholly inapplicable.117 It is possible that both the agency-specific statute and the Vacancies Act may be available to temporarily fill a vacancy.118 The Senate report can be read to support this view: it states that "even with respect to the specific positions in which temporary officers may serve under the specific statutes this bill retains, the Vacancies Act would continue to provide an alternative procedure for temporarily occupying the office."119

However, if two statutes simultaneously apply to authorize acting service, this raises the question of which statute governs in the case of a conflict. If there are inconsistences between the two statutes and an official's service complies with only one of the two statutes, such a situation may prompt challenges to the authority of that acting official.120 The Vacancies Act sets out a detailed scheme delineating three classes of governmental officials that may serve as acting officers121 and expressly limits the duration of an acting officer's service.122 By contrast, agency-specific statutes tend to designate only one official to serve as acting officer123 and often do not specify a time limit on that official's service.124 Accordingly, for example, if an acting officer is designated by the President to serve under the Vacancies Act but is not authorized to serve under the agency-specific statute, a potential conflict may exist between the two laws.125

Where two statutes encompass the same conduct, courts will, if possible, "read the statutes to give effect to each."126 Courts are generally reluctant to conclude that statutes conflict and will usually assume that two laws "are capable of co-existence, . . . absent a clearly expressed congressional intention to the contrary."127 With this principle in the background, judges have sometimes concluded that the Vacancies Act should operate concurrently with these agency-specific statutes, and that government officials should be able to temporarily serve under either statute.128 Accordingly, courts have resolved any potential conflict by holding that whichever statute is invoked is the controlling one.129 At times, however, this method of reconciling the relevant statutes could conflict with the general interpretive rule that more specific statutes should usually prevail over more general ones—even where the more general statutes were enacted after the more specific ones.130

For example, in Hooks ex rel. NLRB v. Kitsap Tenant Support Services, one federal court of appeals rejected a litigant's contention that an agency-specific statute displaced the Vacancies Act and provided "the exclusive means" to temporarily fill a vacant position.131 The agency-specific statute at issue in that case provided that if the office of the NLRB's General Counsel is vacant, "the President is authorized to designate the officer or employee who shall act as General Counsel during such vacancy."132 It also provided for a shorter term of acting service than the Vacancies Act.133 The President, however, had invoked the Vacancies Act to designate an Acting General Counsel.134 The court concluded that "the President is permitted to elect between these two statutory alternatives to designate" an acting officer.135 Accordingly, the court rejected the argument that because the officer's designation did not comply with the agency-specific statute, "the appointment was necessarily invalid."136

But the two statutes governing a vacant office might not always be so readily reconciled. In Hooks, both the Vacancies Act and the agency-specific statute expressly authorized the President to select an acting officer.137 A more difficult question may be raised when an agency-specific statute instead seems to expressly limit succession to a particular official.138 The federal courts recently considered such a contention in a dispute over who was authorized to serve as the Acting Director of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB). The position of CFPB Director became vacant in late 2017, and the President invoked the Vacancies Act to designate Mick Mulvaney, the Director of the U.S. Office of Management and Budget, to serve as Acting Director of the CFPB.139 The Deputy Director of the CFPB, Leandra English, filed suit,140 arguing that she was the lawful Acting Director under an agency-specific statute that provided that the CFPB's Deputy Director "shall . . . serve as acting Director in the absence or unavailability of the Director."141 English argued that the agency-specific statute displaced the Vacancies Act under normal principles of statutory interpretation, as a later-enacted and more specific statute.142

The U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia rejected these arguments and held that the President had permissibly invoked the Vacancies Act to designate Mulvaney as Acting Director.143 In the trial court's view, both statutes were available: the agency-specific statute "requires that the Deputy Director 'shall' serve as acting Director, but . . . under the [Vacancies Act] the President 'may' override that default rule."144 The court invoked two interpretive canons, the rule that statutes should be read in harmony and the rule against implied repeals, and concluded that under the circumstances, an "express statement" was required to displace the Vacancies Act entirely.145 Accordingly, because the agency-specific statute was "silent regarding the President's ability to appoint an acting director," it did not render the Vacancies Act unavailable.146 English appealed this decision to the D.C. Circuit, but decided to discontinue her appeal before the appellate court issued its decision.147

In cases such as Hooks and English, courts are considering how to reconcile statutory provisions. Congressional silence on the relationship between agency-specific provisions and the Vacancies Act can raise difficult questions for courts trying to discern how to resolve any perceived inconsistencies between these statutes. Congress can itself resolve tensions between the Vacancies Act and agency-specific statutes by clarifying the conditions under which these statutes apply. For example, the statute governing vacancies in the office of Attorney General provides that "for the purpose of section 3345 of title 5 the Deputy Attorney General is the first assistant to the Attorney General."148 This statute expressly clarifies—in at least one respect—how the two statutes interact.149

Delegability of Duties

The Vacancies Act only bars acting officials from performing the nondelegable functions and duties of a vacant advice and consent position.150 Unless a statute or regulation requires the holder of an office—and only that officer—to perform a function or duty, the Vacancies Act appears to permit an agency to delegate those duties to any other employee, who may then perform that duty without violating the Vacancies Act.151 Therefore, in many circumstances, an agency officer or employee who has not been appointed to a particular advice and consent position could perform many, if not all, of the responsibilities of that position.

For example, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) considered in 2008 whether a senior official in the Department of Justice's Office of Legal Counsel (OLC), the Principal Deputy Assistant Attorney General, had violated the Vacancies Act by performing the responsibilities of an absent officer, the Assistant Attorney General for the OLC.152 The GAO concluded that the principal deputy had not violated the Vacancies Act because he had merely been performing the duties of his own position, which included the delegated duties of the vacant office.153 The GAO approved of this delegation after reviewing the relevant statutes and regulations and concluding that "there [were] no duties" that could be performed only by the Assistant Attorney General.154

While there are few cases considering what types of duties may be nondelegable for purposes of the Vacancies Act, the courts that have considered the issue have upheld the ability of government officials to perform the delegated duties of a vacant office, so long as the delegation is otherwise lawful.155 Outside the context of the Vacancies Act, courts often presume that delegation is permissible "absent affirmative evidence of a contrary congressional intent."156 However, if a statute expressly prohibited delegation of a duty, that would likely render that duty nondelegable for the purposes of the Vacancies Act.157 Courts have also recognized that some statutes may limit the class of officers to whom a duty is delegable, meaning by implication that the duties are not delegable outside of that specified class.158

As discussed above,159 the text160 and the legislative history161 of the Vacancies Act suggest that Congress intended the Act to bar the performance of only nondelegable functions or duties. This limitation on the scope of the Vacancies Act could potentially undermine one of the Act's primary purposes: to prevent the Executive from appointing "officers of the United States"162 without Senate advice and consent.163 Namely, Section 3347 provides that the Vacancies Act is "the exclusive means" to authorize a person to temporarily perform the duties of a vacant advice and consent office, and specifies that a statute that vests an agency head with the general authority to delegate duties will not suffice to override the Vacancies Act.164 At the same time, however, a general vesting and delegation statute could permit an agency head to delegate any delegable responsibilities of a vacant office to another officer or employee. As a result, if the responsibilities of a particular advice and consent position primarily consist of delegable duties, a general delegation statute could allow an agency employee to perform most of that position's responsibilities even though that employee was not appointed to that position through the advice and consent process—seemingly contrary to the goals of the Vacancies Act.

If Congress were concerned about the ability of an acting officer to perform certain functions or duties of an advice and consent position, it could pass a statute specifying that those functions and duties must be performed by the officer in that position. Then, the Vacancies Act would limit the ability of other officers to perform those duties when the position is vacant.165 Congress could also enact other statutory limitations on the ability of certain officers to delegate their authority.166 Any such statute could place substantive limitations on the types of duties that are delegable or could create procedural limitations on the way in which duties may be delegated.167 Alternatively, if unsatisfied with the current language, Congress could amend the definition of "function or duty" in the Vacancies Act.168

Enforcement Mechanism

The Vacancies Act may be enforced through both the political process and through litigation. Several provisions of the Vacancies Act are centrally enforced through political measures rather than through the courts. For example, while the Act provides that an "office shall remain vacant" unless an acting officer is serving "in accordance with" the Vacancies Act, the statute does not create a clear mechanism to directly implement this provision.169 Accordingly, the text of the Vacancies Act does not contemplate a means of removing any noncompliant acting officers from office. Similarly, if the Comptroller General determines that an officer has served "longer than the 210-day period," the Comptroller General must report this to the appropriate congressional committees.170 However, this provision itself does not require the Comptroller General to make any such determination and contains no additional enforcement mechanism.171 But if the Comptroller General does make such a report to Congress, this reporting mechanism may prompt congressional action pressuring the executive branch to comply with the Vacancies Act, exerted through normal channels of oversight.172 For instance, in March 2018, the House Committee on Ways and Means Subcommittee on Social Security held a hearing on a vacancy in the office of the Commissioner of Social Security.173 The day before the hearing, the Comptroller General issued a letter reporting that the Acting Commissioner, Nancy Berryhill, was violating the Vacancies Act.174 Shortly thereafter, Berryhill reportedly stepped down from the position of Acting Commissioner, serving instead in her position of record as Deputy Commissioner of Operations.175

Arguably, the most direct means to enforce the Vacancies Act is through private suits in which courts may nullify noncompliant agency actions.176 The Vacancies Act appears to render noncompliant actions void.177 As noted earlier,178 a determination that an action is void means that legally, it is as if the action had never been taken in the first place.179 But as a practical matter, not every act taken in violation of the Vacancy Act will necessarily be formally rendered void in a court of law. Although the Vacancies Act is, in a sense, self-executing,180 violations of the Vacancies Act are generally enforced only if a third party with standing (such as a regulated entity that has been injured by agency action) successfully challenges the action as void in court.181 The dearth of case law examining the Vacancies Act suggests that such cases are relatively rare.182

Even in the context of these lawsuits, it is not always entirely clear what relief a court may afford a regulated entity, if the court concludes that an acting officer has violated the Vacancies Act. There is little case law interpreting what it means for an agency action to have "no force or effect"183 in the context of the Vacancies Act. The Supreme Court has suggested that any such actions would be "void ab initio."184 To determine the consequences of such a determination, courts might turn to cases interpreting the judicial review provision of the Administrative Procedure Act (APA).185 The APA directs courts to "hold unlawful and set aside" any agency action that is "arbitrary, capricious, an abuse of discretion, or otherwise not in accordance with law."186 This standard has clear parallels to the statement in the Vacancies Act that any action not "in accordance with"187 the Vacancies Act has "no force or effect."188 However, it does not appear that any court has yet officially recognized this similarity or compared the two standards.

As noted above, in NLRB v. SW General, Inc., the Supreme Court explicitly left open the question of remedy with respect to those officials who are carved out of Section 3348.189 Certain offices are exempt from the provision that nullifies the noncompliant actions of an acting officer,190 and the statute does not otherwise specify what consequences follow, if any, if a person temporarily serving in one of those offices violates the Vacancies Act.191 The D.C. Circuit and the Supreme Court in SW General accepted the parties' apparent agreement that the actions of a noncompliant Acting General Counsel of the NLRB—one of the excepted offices—were voidable.192 The determination that an agency action is voidable, rather than void, might have important consequences for the outcome of any court challenge because it could allow a court to consider mitigating arguments such as the harmless error doctrine or the ratification doctrine.193

However, notwithstanding its decision to accept the parties' litigating postures in that case, the D.C. Circuit expressly left open the possibility that the Vacancies Act might "wholly insulate the Acting General Counsel's actions," so that the actions of an acting officer in one of these named offices are not even voidable.194 It is possible that the Vacancies Act does not undermine the legality of the actions of these specified officers, even if they violate the Act, and that, under this interpretation, these positions could be indefinitely filled by acting officers without consequence under the Vacancies Act.

These questions may be clarified in future litigation, but Congress could, if it so chose, add statutory language more explicitly addressing or otherwise clarifying the consequences of violating the Vacancies Act, particularly with respect to those offices exempt from the enforcement mechanisms contained in Section 3348.195 Congress could also amend the existing enforcement mechanisms, possibly by altering the reporting requirements or by adding additional consequences for violations of the Vacancies Act.196