Introduction

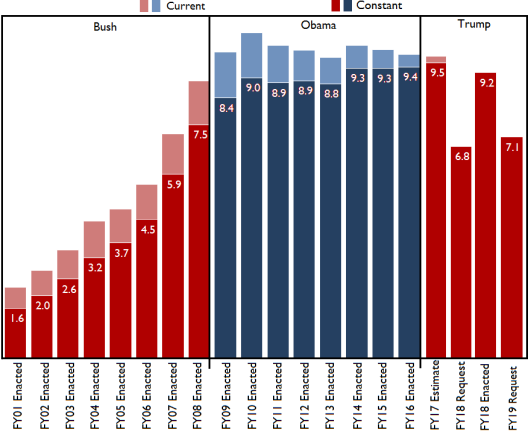

Congress has made global health a high priority for several years, with notable appropriations increases for global health during the George W. Bush Administration. During this period, global-health-related appropriations rose from less than $2 billion in FY2001 to almost $8 billion in FY2008 (Figure 1). Much of the funding increases were provided to support programs, such as the President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) and the President's Malaria Initiative (PMI), which fought HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, and malaria (HTAM). Executive and legislative priorities in global health mostly aligned under the George W. Bush Administration. They largely remained so under the Obama Administration, though some debates emerged on more finite issues, such as the type of HIV/AIDS interventions to support and the extent to which the United States should support international family planning and reproductive health programs.1 It remains to be seen whether legislative and executive priorities will align under the Trump Administration.

While congressional support for global health remained steadfast throughout the Obama Administration, the great recession that began in 2008 slowed overall federal spending, and appropriations for global health programs became relatively stagnant. On average, Congress appropriated roughly $9 billion annually for global health throughout the Obama Administration.

U.S. support for global health has been motivated in large part by concern about emergent and reemerging infectious diseases. Following outbreaks of diseases like severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), HIV/AIDS, and pandemic influenza, several Presidents highlighted the threats such diseases pose to economic development, stability, and security and launched a variety of health initiatives to address them. Congress demonstrated support for each initiative by meeting requested levels, and in some instances exceeded budget proposals.

In 1996, for example, President Bill Clinton issued a presidential decision directive that called infectious diseases a threat to domestic and international security, called for U.S. global health efforts to be coordinated with those aimed at counterterrorism, and established a health advisor on the National Security Council (NSC) for the first time.2 President Clinton later requested $100 million for the Leadership and Investment in Fighting an Epidemic (LIFE) Initiative in 1999 to expand U.S. global HIV/AIDS efforts.3 President George W. Bush recognized the impact of infectious diseases on domestic and global security in his 2002 and 2006 national security strategy papers and created a number of initiatives to address them, including the President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) in 2003, the President's Malaria Initiative (PMI) in 2005, and the Neglected Tropical Diseases (NTD) Program in 2006.4

President Barack Obama also recognized the risk of infectious diseases and made several statements about how their spread across developing countries might affect U.S. security.5 In the 2010 Quadrennial Diplomacy and Development Review (QDDR) and the 2010 National Security Strategy, the Obama Administration advocated for the coordination of global health programs in other areas, such as security, diplomacy, and development. Rather than create an initiative aimed at infectious diseases, President Obama announced the Global Health Initiative (GHI) in 2009 to improve the coordination and impact of U.S. global health efforts. Implementation of the initiative was short-lived, though efforts to deepen integration of global health programs continued throughout the Obama Administration.

Prompted in part by the West Africa Ebola epidemic, the 115th Congress has continued deliberating approaches for strengthening weak health systems while preserving congressional priorities for key global health programs like PEPFAR. The Ebola epidemic not only revealed the threat that weak health systems in developing countries pose to the world, but also exposed gaps in international frameworks for responding to global health crises. Consensus is emerging that health system strengthening is important for protecting advancements in global health and for bolstering international security, though debate abounds regarding the appropriate approach for achieving this goal, as well as identifying the role the United States might play in such efforts, especially in relation to other U.S. global health assistance priorities.

|

|

Source: United Nations webpage on the SDGs at http://www.un.org. |

While legislative and executive commitment to global health remained strong during the Bush and Obama terms, the 115th Congress and the Trump Administration appear to have prioritized funding for global health programs differently. In FY2018, for example, the Trump Administration proposed that funding for global health programs that year be cut by roughly $2.3 billion from FY2017 levels.6 The $6.8 billion FY2018 request included $6.5 billion for related efforts financed through State-Foreign Operations (SFOPS) appropriations and $0.3 billion for global health programs supported through Labor, Health and Human Services, and Education (Labor-HHS) appropriations. In response, Congress funded global health programs in excess of $2.3 billion of the FY2018 budget request in FY2018 and almost $100 million more than FY2017 levels.7 For FY2019, the Trump Administration again has sought to reduce U.S. global health spending by more than $2 billion from FY2018 levels. The $7.1 billion request includes $6.7 billion through SFOPS and $0.4 billion through Labor-HHS. Language in the congressional budget justifications (CBJ) for the State Department and U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) indicated that the Trump Administration "will continue to challenge the global community to devote resources and political commitments to building healthier, stronger, and more self-sufficient nations in the developing world."

Advancements in Global Health

In 2015, the international community adopted the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) to continue progress achieved through the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs).8 The SDGs include 17 goals, the third of which is health (Figure 2). Each SDG includes a set of targets to measure progress. SDG3 includes 13 targets, such as reducing child and maternal mortality; ending epidemics of key communicable diseases like HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis (TB), and malaria; and strengthening state capacity to manage national and global health risks through the achievement of universal health coverage.9 Though the international community has made considerable strides in improving global health, challenges persist. The section below summarizes some advances and challenges.

Maternal and Child Health

Intensified efforts to improve health outcomes during pregnancy and childbirth have led to a 43% reduction in the number of maternal deaths between 1990 and 2015. During this period, the number of maternal deaths fell from roughly 523,000 to an estimated 303,000, about 99% of which occurred in low- and middle-income countries.10 Sub-Saharan Africa and southern Asia were the most affected regions, accounting for 66% and 21% of all maternal deaths, respectively. Roughly one-third of all maternal deaths occurred in Nigeria and India.

Human resource constraints continue to complicate efforts to reduce maternal mortality. In many developing countries, pregnant women deliver their babies without the assistance of trained health practitioners who can help to avert deaths caused by hemorrhage—the leading cause of direct maternal death. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that 27% of all maternal deaths are caused by severe bleeding. Preexisting conditions like HIV/AIDS and malaria are also key contributors to maternal mortality, accounting for roughly 28% of maternal deaths combined.

From 1990 to 2015, the number of child deaths fell from 12.7 million to 5.9 million.11 WHO estimates that more than half of the 16,000 child deaths that occurred in each day of 2015 could have been avoided through low-cost interventions, such as medicines to treat pneumonia, diarrhea, and malaria, as well as tools to prevent the transmission of malaria and HIV/AIDS from mother to child.12 Other factors, like inadequate access to nutritious food, also affect child health. WHO estimates that undernutrition contributes to roughly 45% of all child deaths.13 The risk of a child dying is at its highest within the first month of life, when 45% of all child deaths occur. Children in sub-Saharan Africa are more than 14 times more likely to die before reaching age five than their counterparts in developed countries.

HIV/AIDS

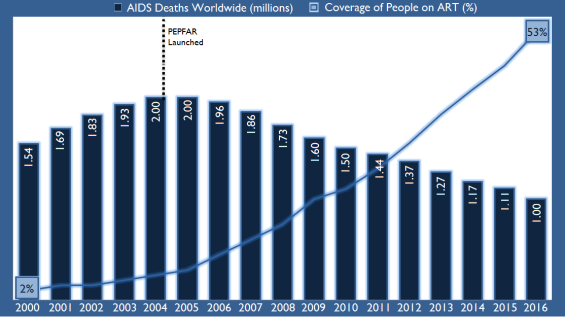

At the end of 2016, almost 37 million people were living with HIV worldwide, nearly 2 million of whom contracted the disease in that year and more than 60% of whom lived in sub-Saharan Africa.14 In 2016, 1 million people died of AIDS, down from 1.9 million in 2003 (before the start of PEPFAR; see Figure 3).

Expanded access to antiretroviral treatments (ARTs) has decreased the number of AIDS deaths. Roughly 53% of HIV-positive people worldwide were on ART in 2016, up from 4% in 2003. The United States has contributed substantially to improving global access to ART through PEPFAR and its support for the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (Global Fund). An estimated 19.5 million people worldwide were on ART at the end of 2016. The Office of the Global AIDS Coordinator (OGAC) indicated that by 2016 the United States was supporting ART for almost 11.5 million people worldwide through PEPFAR programs and U.S. contributions to the Global Fund.15

|

|

Source: Created by CRS from the UNAIDS database at http://aidsinfo.unaids.org/. |

Other Infectious Diseases

In recent years, a succession of new and reemerging infectious diseases have caused outbreaks and pandemics that have affected thousands of people worldwide: Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS, 2003), Avian Influenza H5N1 (2005), Pandemic Influenza H1N1 (2009), Middle East Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV, 2013), Ebola in West Africa (2014-2016), the Zika virus (2015-2016), and Yellow Fever in Central Africa (2016) and South America (2016-2017). The United States has played a leading role in launching and implementing the Global Health Security Agenda (GHSA), a multilateral effort to improve the capacity of countries worldwide to detect, prevent, and respond to diseases with pandemic potential.

While the world faces threats from new diseases, long-standing diseases like tuberculosis (TB) also pose a threat to global health security. Among infectious diseases, TB is the most common cause of death worldwide. Multi-drug resistant (MDR)-TB is of growing concern, as it is more expensive and difficult to treat. Only half of all MDR-TB patients survive.16 WHO asserts that global funding for addressing MDR-TB is insufficient and weaknesses in health systems complicate efforts to treat the disease and prevent its further spread.

Global Health Appropriations

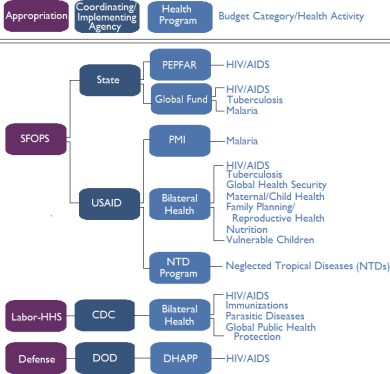

Congress funds most global health assistance through two appropriations bills: State-Foreign Operations and Related Programs (SFOPS) and Labor, Health and Human Services, and Education (Labor-HHS; see Figure 4). These bills are used to fund global health efforts implemented by USAID and the U.S. Centers for Defense Control and Prevention (CDC), as well as PEPFAR programs that are coordinated by the Department of State and implemented by several U.S. agencies. Through PEPFAR, the United States contributes to multilateral efforts to combat HIV/AIDS, TB, and malaria (HATM), including the Global Fund and the Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS).

State-Foreign Operations Appropriations

The majority of appropriations for global health programs are provided through the Global Health Programs Account (GHP) in State-Foreign Operations appropriations. More than 80% of the funds are used for fighting HATM through bilateral programs and the Global Fund. Table A-2 outlines global health funding through State-Foreign Operations appropriations.

Labor-HHS Appropriations

Through Labor-HHS appropriations, Congress funds global health programs implemented by CDC and global HIV/AIDS research conducted by the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Labor-HHS appropriations do not specify an amount for NIH global HIV/AIDS research, though the Administration typically includes these amounts in reports on PEPFAR funding.

Table A-3 outlines global health spending through Labor-HHS.

Implementing Agencies and Departments

This section describes the global health activities implemented or coordinated by each agency that received appropriations, as described above. This discussion is limited to those agencies and departments for which Congress provides funding specifically for global health: USAID, State, and CDC. Agencies may use internal funding to contribute to additional global health efforts.

U.S. Agency for International Development17

USAID groups its global health activities into three areas: saving mothers and children, creating an AIDS-Free generation, and fighting other infectious diseases. A summary of these efforts is described below.

- Saving Mothers and Children. USAID seeks to save the lives of women and children by reducing morbidity and mortality from vaccine-preventable deaths, malaria, and undernutrition; supporting vulnerable children and orphans; and increasing access to family planning and reproductive health services.

- Creating an AIDS-Free Generation. USAID aims to combat HIV/AIDS by supporting voluntary counseling and testing, awareness campaigns, and the supply of antiretroviral medicines, among other activities.

- Fighting Other Infectious Diseases. USAID works to address a number of infectious diseases and resultant outbreaks. Congress appropriates a specific amount for malaria, TB, NTDs, pandemic influenza, and other emerging threats.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention18

Through Labor-HHS appropriations, Congress specifies support for the following CDC global health activities:

- HIV/AIDS. CDC works with Ministries of Health (MOHs) and global partners to increase access to integrated HIV/AIDS care and treatment services, strengthen and expand high-quality laboratory services, conduct research, and support resource-constrained countries' efforts to develop sustainable public health systems.

- Parasitic Diseases and Malaria. CDC aims to reduce death and illness associated with parasitic diseases, including malaria, by capacity building and enhancing surveillance, monitoring and evaluation, vector control, case management, and diagnostic testing. CDC also identifies best practices for parasitic disease programs and conducts epidemiological and laboratory research for the development of new tools and strategies.

- Global Immunization. CDC works to advance several global immunization initiatives aimed at preventable diseases, including polio, measles, rubella, and meningitis; accelerate the introduction of new vaccines; and strengthen immunization systems in priority countries through technical assistance, monitoring and evaluation, social mobilization, and vaccine management.

- Global Public Health Capacity Development. CDC helps MOHs develop Field Epidemiology Training Programs (FETPs) that strengthen health systems by enhancing laboratory management, applied research, communications, program evaluation, program management, and disease detection and response. Through the Global Disease Detection (GDD) program, CDC builds capacity to monitor, detect, and assess disease threats and responds to requests for support in humanitarian assistance from other U.S. and U.N. agencies, as well as NGOs.

Department of State

Through OGAC, the State Department leads PEPFAR and oversees all U.S. spending on global HIV/AIDS, including those appropriated to other agencies and multilateral groups like the Global Fund and UNAIDS. In July 2012, the Obama Administration announced an expansion of the State Department's engagement in global health with the launch of the Office of Global Health Diplomacy (OGHD).19 The office seeks to "guide diplomatic efforts to advance the United States' global health mission" and provide "diplomatic support in implementing the Global Health Initiative's principles and goals."20 The Global AIDS Coordinator also leads OGHD. The key objectives of the OGHD are to

- provide ambassadors with expertise, support, and tools to help them effectively work with country officials on global health issues;

- elevate the role of ambassadors in their efforts to pursue diplomatic strategies and partnerships within countries to advance health;

- support ambassadors to build political will among partner countries to improve health and strengthen health systems;

- strengthen the sustainability of health programs by helping partner countries meet the health care needs of their own people and achieve country ownership; and

- foster shared responsibility and coordination among donor nations, multilateral institutions, civil society, the private sector, faith-based organizations, foundations, and community members.

Department of Defense

The Department of Defense (DOD) carries out a wide range of health activities abroad, including infectious disease research, health assistance following natural disasters and other emergencies, and training of foreign health workers and officials.21 The DOD HIV/AIDS Prevention Program (DHAPP) is the only global health program for which Congress has appropriated funds to the department for any global health activity. As an implementing agency of PEPFAR, DOD also receives transfers from the Department of State for HIV/AIDS research, care, treatment, and prevention programs.22

Table A-3 in the Appendix outlines annual funding for DHAAP.

Presidential Health Initiatives

Several Presidents have launched health initiatives to advance their priorities, some of which are enduring. The section below describes health initiatives that were launched during the George W. Bush Administration and continue to be implemented.

President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR)23

In January 2003, President George W. Bush announced PEPFAR, a government-wide initiative to combat global HIV/AIDS. Later that year, Congress enacted the Leadership Act (P.L. 108-25), which authorized $15 billion to be spent from FY2004 to FY2008 on bilateral and multilateral HIV/AIDS, TB, and malaria programs and authorized the creation of OGAC to oversee all U.S. spending on global HIV/AIDS. OGAC distributes the majority of the funds it receives from Congress for bilateral HIV/AIDS programs and multilateral efforts, like those carried out by the Global Fund.

In 2008, Congress enacted the Lantos-Hyde Act (P.L. 110-293), which among other things amended the Leadership Act to authorize the appropriation of $48 billion for global HIV/AIDS, TB, and malaria efforts from FY2009 to FY2013. In November 2013, Congress enacted P.L. 113-56, the PEPFAR Stewardship and Oversight Act.24 The act did not authorize a specific amount of funds for the program, though it continues to receive bipartisan support.

President's Malaria Initiative (PMI)25

In June 2005, President George W. Bush announced PMI to expand and coordinate U.S. global malaria efforts. PMI was originally established as a five-year, $1.2 billion effort to halve the number of malaria-related deaths in 15 sub-Saharan African countries through the expansion of four prevention and treatment techniques: indoor residual spraying (IRS), insecticide-treated nets (ITNs), artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACTs), and intermittent preventive treatment for pregnant women (IPTp).26 The Obama Administration expanded the goals of PMI to halving the burden of malaria among 70% of at-risk populations in Africa by 2014 and added the Democratic Republic of Congo, Guinea, Nigeria, and Zimbabwe as partner countries.

The Leadership Act, as amended, authorized the establishment of the U.S. Malaria Coordinator at USAID to oversee implementation of related efforts and is advised by an Interagency Advisory Group that includes representatives from USAID, HHS, State, DOD, the National Security Council (NSC), and the Office of Management and Budget (OMB).

Neglected Tropical Disease (NTD) Program27

The NTD Program started in 2006, following language in FY2006 State-Foreign Operations appropriations that directed USAID to make available at least $15 million for fighting seven NTDs.28 It is managed by USAID and jointly implemented by USAID and CDC. When the program was launched, the George W. Bush Administration sought to support the provision of 160 million NTD treatments for 40 million people in 15 countries. In 2008, President Bush reaffirmed his commitment to tackling NTDs and proposed spending $350 million from FY2008 through FY2013 on expanding the program to 30 countries. In 2009, the Obama Administration amended the targets of the NTD program and called for the United States to support halving the prevalence of NTDs among 70% of the affected population in target countries.

Global Health Spending by Other Countries

Funding for global health assistance has grown over the past decade (Figure 5). During economic recession periods in Europe and the United States, rates of growth for global health aid slowed, but health aid remained mostly level. Global funding to curb the 2014 West Africa Ebola outbreak contributed to a spike in global health aid in 2015.

The United States provides more official development assistance (ODA) for health than any other country in the Development Assistance Committee (DAC).29 In 2016, U.S. spending on global health accounted for more than 60% of all health aid provided by DAC members (Figure 5). The United States also apportions more of its foreign aid to improving global health than most other DAC countries (Figure 6). The United States apportioned 30.5% of its foreign aid to health assistance in 2016. Among top health aid donors, the Netherlands allotted the second-largest share (16.4%) of its ODA to health assistance in 2016, followed by the United Kingdom (13.3%), Japan (3.4%), and Germany (2.6%).

|

Figure 5. Official Development Assistance for Health, 2007-2016 (2015 constant U.S. $ billions and annual percentage change) |

|

|

Source: Created by CRS from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) website on statistics at http://www.oecd.org/statistics/, accessed on March 23, 2018. |

|

Figure 6. DAC Aid and Health Aid by Country, 2016 (current U.S. $ billions) |

|

|

Source: Created by CRS from the OECD website on on statistics at http://www.oecd.org/statistics/, accessed on March 23, 2018. |

Issues for the 115th Congress

Congressional support for global health assistance focuses primarily on specific health conditions, especially HIV/AIDS, TB, and malaria. Almost 75% of FY2018 global health appropriations, for example, were aimed at controlling HIV/AIDS (61%), TB (3%), and malaria (10%).30 The emergence of Ebola in West Africa,31 yellow fever outbreaks in densely populated cities in Angola and Brazil,32 as well as the spread of tropical diseases like Zika33 and dengue fever to Western nations has heightened concerns about the ability of low- and middle-income countries to prevent and respond to an infectious disease outbreak with pandemic potential, as well as the vulnerability of the United States and other Western states to the importation of such diseases.

Whereas the United States demonstrated strong support for the Global Health Security Agenda under the Obama Administration, it is unclear whether the Trump Administration will maintain such support. Each of the global health budget requests from the Trump Administration included an almost $2 billion reduction in U.S. global health spending. In contrast, Congress mostly maintained global health funding levels in FY2018 and is considering the FY2019 budget request. Congress is also debating responses to efforts by the Trump Administration to reinstate and expand the Mexico City Policy and whether to authorize the extension of PEPFAR. The section below discusses these issues.

Strengthening Health Systems

The global spread of recent disease outbreaks, including Ebola and Zika, has intensified debates about the advantages and disadvantages of disease-specific funding. The international community has vacillated between systems- and disease-focused support for global health. In the 1970s and 1980s, for example, the international community sought to ensure "an acceptable level of health for all the people of the world by the year 2000" through bolstering primary health systems.34 While advances were made, some global health experts asserted that weak health systems impeded efforts to improve health outcomes and began to advocate for targeting heath assistance through nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) rather than host governments. Supporters of targeted health assistance asserted that vertical programs facilitate monitoring and evaluation of impact and directly funding NGOs lessens the likelihood that health assistance will be wasted or diverted. Opponents argued that disease-specific programs exacerbate human resource shortages in the public sector and further weaken health systems when parallel bureaucracies are established and government authorities are circumvented.

The international community agreed in 2000 to a targeted approach and galvanized around the Millennium Development Goals. While progress was made on achieving the MDGs, the health-related goals were not completely met. Many donors and partner countries have come to agree that progress made by disease-specific programs is being undermined by weak health systems that are ill-equipped to address growing global health challenges like noncommunicable diseases and infectious diseases with pandemic potential. Much of U.S. and international mechanisms for improving global health remain focused on particular diseases, though world leaders are deliberating how to attain the Sustainable Development Goal calling for "good health and well-being" by 2030, which includes achieving "universal health coverage" among the related targets.

Congressional interest in bolstering weak health systems was particularly strong during the Ebola outbreak. Committees held several hearings on related topics and Members deliberated legislative drafts aimed at strengthening health systems worldwide. Congressional discussions about health system strengthening have been waning though some interest remains. In the 115th Congress, for example, H.R. 244, Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2017, included language urging continued support for the Fogarty International Center and its efforts to strengthen health systems worldwide.35 Other legislative actions to signal support for health system strengthening include introduction of H.Res. 342, Recognizing the Essential Contributions of Frontline Health Workers to Strengthening the United States National Security and Economic Prosperity, Sustaining and Expanding Progress on Global Health, and Saving the Lives of Millions of Women, Men, and Children Around the World.

Bolstering Pandemic Preparedness

Since 1980, infectious diseases have caused outbreaks that have been occurring with greater frequency and have been causing higher numbers of human infections.36 Outbreaks are caused by diseases that were once concentrated in tropical regions, including Ebola and Zika, are spreading through international travel. At the same time, long-standing diseases like tuberculosis and malaria are becoming increasingly resistant to available drugs and also threaten global health.

The United States has been a key supporter in global efforts to bolster pandemic preparedness in low- and middle- income countries. In February 2014, the United States and WHO jointly announced the Global Health Security Agenda. Former President Barack Obama committed in July 2015 that the United States would spend more than $1 billion in support of GHSA in 31 countries and the Caribbean Community.37 USAID reports that it has used $343 million of emergency Ebola funds to advance GHSA,38 and CDC has obligated nearly all of the $597 million that Congress provided through emergency appropriations in support of GHSA.39

The extent to which the Trump Administration will support GHSA remains to be seen. On the one hand, former Secretary of State Rex Tillerson asserted that "the United States advocates extending the Global Health Security Agenda until the year 2024."40 On the other hand, FY2018 and FY2019 global health budget requests from the Trump Administration proposed eliminating regular appropriations for global health security and only using funds from the FY2015 Ebola emergency appropriations for related efforts.41

The emergency appropriations that CDC and USAID have been using to expand support for the GHSA will expire at the end of FY2019. A consortium of health groups wrote to the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services expressing concerns about press reports indicating that CDC would dramatically scale back GHSA-related activities at the end of FY2019 if additional funds were not provided.42 Recent efforts to rescind $252 million in unobligated Ebola emergency funds may further constrain available resources for pandemic preparedness.43 It is unclear whether the 115th Congress will provide supplemental funds to maintain ongoing global health security efforts. In its report on H.R. 5515, National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2019, the House Committee on Armed Services indicated that the "2014 Ebola outbreak demonstrated the need for a prompt and efficient response to a highly infectious disease outbreak" and directed the Secretary of Defense, in coordination with the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response at the Department of Health and Human Services, to brief the committee no later than June 1, 2019, on the development of an action plan focused on efforts to counter emerging infectious disease threats. The plan should "identify capability gaps; actions taken to improve point-of-care diagnostics linked to disease surveillance and information-sharing networks; examine infectious disease emergency response teams; capabilities for medical evacuation of patients with high consequence infections; gaps in infection prevention and control standards; and research efforts focused on medical countermeasures."

Considering the FY2019 Budget Request

Congressional appropriations for global health programs mostly exceeded budget requests throughout the Bush and Obama Administrations. The FY2018 and FY2019 budget requests from the Trump Administration raised considerable debate, however, because each of them sought to reduce global health funding by roughly $2 billion, a significantly deeper cut than has been requested by the previous two administrations (Table A-5). Congress declined to adopt the FY2018 budget request and mostly maintained funding for global health programs (Table 1).

The 115th Congress is considering the FY2019 budget request, which includes over $7 billion for global health assistance, roughly 24% less than FY2018 enacted levels. The Trump Administration proposes reducing the USAID global health budget by nearly 40% through the elimination of funding for global health security, vulnerable children, and HIV/AIDS programs and reductions to other health programs. The Trump Administration also recommended cuts for PEPFAR programs managed by the State Department (-11%), the Global Fund (-31%), and CDC global health programs (-16%). For detailed information on the FY2019 budget request and prior funding levels, see the Appendix.

|

FY2016 Enacted |

FY2017 Enacted |

FY2018 Request |

FY2018 Enacted |

FY2019 Request |

FY18 Enacted-FY2019 Request |

|||||

|

State-Global Health Programs |

4,320.0 |

4,320.0 |

3,850.0 |

4,320.0 |

3,850.0 |

-11% |

||||

|

USAID-Global Health Programs |

2,833.5 |

2985.0 |

1,505.5 |

3,020.0 |

1,927.5 |

-36% |

||||

|

Global Fund |

1,350.0 |

1,350.0 |

1,125.0 |

1,350.0 |

925.1 |

-31% |

||||

|

SFOPS Appropriations Total |

8,503.5 |

8,655.0 |

6,480.5 |

8,690.0 |

6,702.6 |

-23% |

||||

|

SFOPS Ebola Emergency |

0.0 |

70.0 |

322.5a |

0.0 |

72.5 |

|||||

|

SFOPS Zika Emergency |

145.5 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

|||||

|

SFOPS Appropriations Total Including Emergency Appropriations |

8,649.0 |

8,725.0 |

6,803.0 |

8,690.0 |

6,775.1 |

n/a |

||||

|

CDC |

426.6 |

426.4 |

349.9 |

488.6 |

409.0 |

-16% |

||||

|

NIH Global AIDS Research |

431.1 |

431.9 |

n/a |

|||||||

|

Labor-HHS Appropriations Total |

857.7 |

858.3 |

||||||||

|

Labor-HHS Ebola Emergency |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

n/a |

||||

|

Labor-HHS Zika Emergency |

394.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

n/a |

||||

|

Labor-HHS Appropriations Total Including Emergency Appropriations |

1,251.7 |

858.3 |

||||||||

|

Total Global Health Appropriations |

9,361.2 |

9,513.3 |

||||||||

|

Total Global Health, Including Emergency Appropriations |

9,900.7 |

9,583.3 |

||||||||

Source: Created by CRS from congressional budget justifications and correspondence with USAID and CDC legislative affairs offices.

Abbreviations: U.S. Department of State (State), U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (Global Fund), State-Foreign Operations (SFOPS), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), National Institutes of Health (NIH), U.S. Departments of Labor, Health and Human Services, and Education (Labor-HHS) Appropriations.

Notes:

a. The Administration proposed transferring $322.5 million of unobligated funds provided for the Ebola outbreak to USAID for malaria ($250 million) and other global health security ($72.5 million).

b. In the explanatory report of P.L. 113-235, Further Continuing Appropriations Act of 2015, Congress authorized the provision of over $5 billion in supplemental funds to be expended through FY2019 for containing the 2014 West Africa Ebola outbreak. Agencies and departments report to Congress as they draw on these funds. Spending from this source is ongoing in FY2018.

c. The Administration did not request a particular amount for NIH international HIV/AIDS research. Amounts that the Administration spends on NIH international HIV/AIDS research is drawn from the overall budget of the Office of AIDS Research. Those amounts are reported annually in congressional budget justifications.

d. To maintain consistency across fiscal years, CRS did not aggregate the total since information is not yet available on NIH spending on international HIV/AIDS research.

Protecting Life in Global Health Assistance

In 1984, former President Ronald Reagan issued what has become known as the "Mexico City policy," which required foreign nongovernmental organizations receiving USAID family planning assistance to certify that they would not perform or actively promote abortion as a method of family planning, even if such activities were conducted with non-U.S. funds.44 The policy has been rescinded and reinstituted across Administrations. Under the Trump Administration, the policy was reinstated, renamed to Protecting Life in Global Health Assistance (PLGHA), and expanded to apply to all global health programs.

Global health experts are working to measure the impact of the PLGHA policy. Opponents maintain that the policy imperils all global health programs because some health providers may not be able to disentangle FP/RH, HIV/AIDS, and maternal and child health services from one another, particularly in areas with limited access to health workers and facilities. This integration of services was accelerated during the Obama Administration when NGOs were encouraged to colocate services in one facility, including contraceptive care, HIV/AIDS services, prenatal checkups, immunizations, and information or referrals on safe abortion.45 A number of global health experts wrote a letter to former Secretary of State Tillerson warning that the PLGHA policy could reduce access to reproductive health commodities and services that are unrelated to abortions.46 Some Members of Congress have agreed with those arguing that implementing PLGHA would reduce efficiencies, depress access to some health services, and worsen health outcomes in participating countries.47

Supporters of the policy maintain that although existing laws ban U.S. funds from being used to perform or promote abortions abroad, money is fungible and the PLGHA policy closes loopholes. The Trump Administration contends that "the impact on those service providers is going to be minimal,"48 and has committed to routinely "capture, monitor, and use age- and sex- disaggregated data, by partner and by site, to track precisely whether and to what extent the policy has affected life-saving activities related to HIV/AIDS."49

On February 6, 2018, the Department of State released a report entitled, Protecting Life in Global Health Assistance Six-Month Review. The report indicated that as of September 30, 2017, "three centrally funded prime partners and 12 sub-awardee implementing partners" working with USAID declined funding due to the terms of the PLGHA policy.50 One implementing partner with the Department of Defense and no partners with the Department of Health and Human Services declined U.S. assistance. The Administration has agreed with observations that it is too early to determine any effects the policy will have on programming, and has committed to conduct another assessment in December 2018.51

Since the Mexico City Policy was first established, Members on both sides of the issue have introduced legislation to permanently enact or repeal the policy. In the 115th Congress, H.R. 671 and S. 210, Global Health, Empowerment, and Rights Act, would prohibit the application of the PLGHA to foreign NGOs.

Authorizing PEPFAR

Legislation that authorizes appropriations for PEPFAR and describes congressional priorities for the initiative expires September 30, 2018.52 PEPFAR continues to receive bipartisan support and is being maintained by the Trump Administration, though at lower levels than previous administrations. The first budget request from the Trump Administration, issued in early 2017, sought roughly $5 billion for global HIV/AIDS programs in FY2018 (about $1 billion less than FY2017 enacted levels), including $1.1 billion for a U.S. contribution to the Global Fund. The House and Senate Appropriations Committees disagreed with the budget proposal and recommended that HIV/AIDS funding levels in FY2018 remain mostly at FY2017 levels.

Following the release of the FY2018 budget and Strategy, some HIV/AIDS advocates and Members of Congress questioned the Administration's commitment to controlling the global AIDS epidemic and expressed concern about whether people on ART would lose coverage due to spending cuts.53 The Administration maintained that requested levels would enable PEPFAR to "accelerate efforts toward achieving epidemic control in 13 high impact epidemic control countries."54 Outside of these countries, the Administration asserted that "PEPFAR will maintain its current level of antiretroviral treatment through direct service delivery and expand both HIV prevention and treatment services, where possible, through increased performance and efficiency gains."55

The Trump Administration proposal to maintain treatment levels is a departure from the Bush and Obama Administrations, under which executive and legislative priorities for PEPFAR included steadily increasing the number of people receiving ART through PEPFAR programs. Some Members of Congress have challenged the Trump Administration's approach to PEPFAR, raising questions about whether executive and legislative consensus around broadening the reach of PEPFAR and advancing the global goal of achieving an AIDS-free generation is fraying.56

The Oversight Act, the current iteration of PEPFAR authorizing legislation, neither includes performance targets nor specifies countries in which PEPFAR should operate, as previous authorizing legislation had. The lack of such details in the legislation may have suggested broad consensus at the time on PEPFAR priorities. Concerns expressed by some Members of Congress about Trump Administration priorities for PEPFAR may prompt new discussions about whether such details should be included in future authorization legislation. Key discussions about extending PEPFAR have centered around three key policy issues: performance targets, focus countries, and the Mexico City Policy.

Performance Targets. The Lantos-Hyde Act mandated that PEPFAR programs support ART for at least 4 million people by the end of FY2013. In 2011, President Obama announced that PEPFAR would help the world achieve the global target of an AIDS-free generation by helping 6 million people get on ART by the end of 2013—2 million more than originally planned.57 Congress did not include treatment targets in the Oversight Act, though President Obama steadily increased treatment goals throughout his tenure. Members concerned about plans announced by the Trump Administration to increase treatment levels in the 13 priority countries while maintaining treatment levels elsewhere might consider including treatment targets in authorizing legislation. Others may seek to maintain executive branch flexibility over determining treatment targets and program goals more broadly.

Focus Countries. The Leadership Act named 14 priority countries in which the bulk of PEPFAR resources were to be invested.58 The Lantos-Hyde Act later named Vietnam as the 15th focus country. By the end of FY2013 (when authorization for funding PEPFAR was set to expire), roughly 86% of all bilateral PEPFAR resources were spent in these 15 countries. The Oversight Act did not identify countries where PEPFAR should concentrate its investments, though it defined a partner country as any country receiving at least $5 million from the U.S. government for HIV/AIDS assistance. The Trump Administration has proposed concentrating efforts in 13 countries (bolded countries are also among the 15 original focus countries): Botswana, Cote d'Ivoire, Haiti, Kenya, Lesotho, Malawi, Namibia, Rwanda, Swaziland, Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. In these countries, the Administration commits that PEPFAR will work with other partners to ensure that 95% of HIV-positive people know their status, 95% of those who know their status are on ART, and that 95% of those on treatment maintain suppressed viral loads for at least three years.59 These efforts, the Administration maintains, will lead to AIDS epidemic control.

Some observers criticized the strategy, asserting that it could lead to a resurgence of the epidemic, while others applauded the move and described the strategy as "reassuring."60 Congress could consider evaluating where PEPFAR funding is concentrated and mandating which countries should be deemed priorities, as it had in the Leadership and Lantos-Hyde Acts. It might also consider identifying criteria for establishing a priority country.

Protecting Life in Global Health Assistance. It remains to be seen what impact, if any, the PLGHA policy may have on global HIV/AIDS programs. Debates about the possible effects of the PLGHA policy on PEPFAR programs mirror broader debates, as discussed above. In 2003, the Bush Administration exempted PEPFAR programs from the Mexico City Policy.61 Uncertainty about the impact of PLGHA on PEPFAR programs might prompt Congress to consider including language requiring regular monitoring, assessment, and reporting on the impact of the PLGHA policy in any PEPFAR reauthorizing legislation. Congress might also consider including exemption language in appropriations legislation or PEPFAR reauthorization legislation as well as developing standalone legislation that exempts PEPFAR or certain elements of PEPFAR from the policy.

Outlook

Despite ongoing debates about the utility or appropriate levels of foreign assistance, global health programs have, in general, continued to receive bipartisan support, possibly indicating that global health remains a congressional priority. While the international community has achieved significant gains in curbing preventable deaths, some experts are concerned about looming health challenges. In a growing number of countries, deaths and illness from noncommunicable diseases (like diabetes, cancer, and heart disease) are outnumbering fatalities and ailments from communicable diseases (like malaria and HIV/AIDS). Many middle-income countries like South Africa face dual epidemics of diseases associated with growing prosperity (diabetes) and persistent poverty (vaccine-preventable child deaths). In the absence of higher spending levels, bolstering health systems will likely gain greater importance in U.S. global health programs.

Appendix. Global Health Funding Tables, by Agency and Appropriation Vehicle

Table A-1. U.S. Global Health Funding, by Agency and Appropriation Vehicle: FY2001-FY2019 Request

(constant 2018 U.S. $ millions)

|

Agency/Program |

Bush Administration |

Obama Administration |

Trump Administration |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

FY2001-FY2008 Enacted Total |

FY2001-FY2008 Average |

FY2009-FY2016 Enacted Total |

FY2009-FY2016 Enacted Average |

FY2017 Enacted |

FY2018 Request |

FY2018 Enacted |

FY2019 Request |

|||||||||||||||

|

State HIV/AIDS |

8,663.6 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

Global Fund |

2,101.1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

USAID |

10,198.3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

SFOPS Total |

19,789.3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

SFOPS Ebola Emergency |

0.0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

SFOPS Zika Emergency |

0.0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

SFOPS Total, Including Emergency Appropriations |

19,789.3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

CDC |

1,942.0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

NIH Global AIDS Research |

1,935.2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

Global Fundc |

757.3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

DOL HIV/AIDSd |

30.3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

Labor-HHS Total |

4,665.0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

Labor-HHS Ebola Emergency |

0.0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

Labor-HHS Zika Emergency |

0.0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

Labor-HHS Total, Including Emergency Appropriations |

4,665.0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

DOD HIV/AIDSf |

42.1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

Total Global Health |

24,496.4 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

Total Global Health, Including Emergency Appropriations |

24,496.4 |

|

|

|

9,380.4 |

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

Source: Created by CRS from appropriations legislation and correspondence with CDC and USAID legislative affairs offices.

Acronyms: U.S. Department of State (State), Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (Global Fund), U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs Appropriations (SFOPS), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), National Institutes of Health (NIH), U.S. Department of Labor (DOL), Labor, Health and Human Services, Education, and Related Appropriations (Labor-HHS), U.S. Department of Defense (DOD), not specified (n/s).

Notes: Excludes funding for global health through other accounts in State, Foreign Operations appropriations, such as the Economic Support Fund (ESF).

Figures in FY2001-2008 include funds appropriated to multiple accounts within State-Foreign Operations. Figures in FY2009-FY2014 only include appropriations to the Global Health Programs account. Additional resources that CDC may provide for global health programs through other accounts are not included here. CDC, for example, spends a portion of its tuberculosis budget on global activities.

a. The Trump Administration proposed transferring $322.5 million of unobligated funds provided for the Ebola outbreak to USAID for malaria ($250 million) and other global health security ($72.5 million).

b. The Administration did not request a particular amount for NIH international HIV/AIDS research. Amounts that the Administration spends on NIH international HIV/AIDS research is drawn from the overall budget of the Office of AIDS Research. Those amounts are reported annually in congressional budget justifications.

c. From FY2001 through FY2011, Congress provided funds for U.S. contributions to the Global Fund through SFOPS and Labor-HHS appropriations. After then, Congress provided all funds for U.S. Global Fund contributions to the State Department.

d. Congress appropriated funds to the Department of Labor for global HIV/AIDS activities from FY2001 through FY2005. After then, all support for DOL HIV/AIDS activities were provided through appropriations to the State Department.

e. To maintain consistency across fiscal years, CRS did not aggregate the total since FY2018 and FY2019 requested levels for NIH research are not yet available.

f. Congress appropriated funds to the Department of Defense for global HIV/AIDS activities from FY2001 through FY2015. After then, all support for DOD HIV/AIDS activities were provided through appropriations to the State Department.

Table A-2. Global Health State-Foreign Operations Funding: FY2001-2019 Request

(constant 2018 U.S. $ millions)

|

Agency/Program |

Bush Administration |

Obama Administration |

Trump Administration |

||||||||||||

|

FY2001-FY2008 Enacted Total |

FY2001-FY2008 Enacted Average |

FY2009-FY2016 Enacted Total |

FY2009-FY2016 Enacted Average |

FY2017 Enacted |

FY2018 Request |

FY2018 Enacted |

FY2019 Request |

||||||||

|

HIV/AIDS |

8,663.6 |

1,083.0 |

31,185.2 |

3,898.2 |

4,228.5 |

|

|

3,936.1 |

|||||||

|

Global Fund |

927.4 |

115.9 |

8,515.0 |

1,064.4 |

1,321.4 |

|

|

945.8 |

|||||||

|

State Total |

9,591.0 |

1,198.9 |

39,700.2 |

4,962.5 |

5,550.0 |

|

|

4,881.9 |

|||||||

|

HIVAIDS |

2,412.7 |

301.6 |

2,459.6 |

307.4 |

323.0 |

|

|

0.0 |

|||||||

|

Global Fund |

1,173.7 |

146.7 |

85.0 |

10.6 |

0.0 |

|

|

0.0 |

|||||||

|

Tuberculosis |

498.3 |

62.3 |

1,614.9 |

201.9 |

235.9 |

|

|

182.4 |

|||||||

|

Malaria |

827.9 |

103.5 |

4,452.9 |

556.6 |

739.0 |

|

|

689.1 |

|||||||

|

Maternal and Child Health |

2,243.2 |

280.4 |

4,430.7 |

553.8 |

797.3 |

|

|

633.5 |

|||||||

|

Nutritionb |

0.0 |

0.0 |

697.6 |

87.2 |

122.4 |

|

|

80.3 |

|||||||

|

Vulnerable Children |

115.5 |

14.4 |

132.0 |

16.5 |

22.5 |

|

|

0.0 |

|||||||

|

Family Planning/Rep. Health |

2,416.9 |

302.1 |

3,748.9 |

468.6 |

512.9 |

|

|

308.8 |

|||||||

|

Neglected Tropical Diseases |

36.6 |

4.6 |

589.3 |

73.7 |

97.9 |

|

|

76.7 |

|||||||

|

Pandemic Influenza/Other |

473.5 |

59.2 |

646.5 |

80.8 |

71.0 |

|

|

0.0 |

|||||||

|

USAID Total |

10,198.3 |

1,274.8 |

18,857.5 |

2,357.2 |

2,921.8 |

|

|

1,970.6 |

|||||||

|

SFOPS Total |

19,789.3 |

2,473.7 |

58,557.7 |

7,319.7 |

8,471.8 |

|

|

6,852.5 |

|||||||

|

Ebola Emergencyc |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

68.5 |

|

|

74.1 |

|||||||

|

Zika Emergency |

0.0 |

0.0 |

139.5 |

17.4 |

0.0 |

|

|

0.0 |

|||||||

|

SFOPS Total, Including Emergency Appropriations |

19,789.3 |

2,473.7 |

58,697.2 |

7,337.2 |

8,540.3 |

|

|

|

|||||||

Source: Appropriations legislation, congressional budget justifications, and personal communication with USAID Office of Legislative Affairs.

Acronyms: Reproductive Health (Rep. Health), U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), State, Foreign Operations (SFOPS), not specified (n/s). Figures in FY2001-2008 include funds appropriated to multiple accounts within State-Foreign Operations. Figures in FY2009-FY2014 only include appropriations to the Global Health Programs Account.

Notes: Excludes funding for global health through other accounts in State, Foreign Operations appropriations, such as the Economic Support Fund (ESF).

a. The House Appropriations Committee recommended including $132.5 million for a contribution to the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) within the $2,651.0 million it recommended providing for USAID global health programs. This amount is included in the maternal and child health subcategory above.

b. Congress began to appropriate funds for nutrition in 2009. Until then, nutrition funds were included in appropriations for maternal and child health programs.

c. Includes amounts provided directly for emergency Ebola operations, as well as amounts to be transferred from unobligated emergency Ebola funds.

d. The Administration proposed transferring $322.5 million of unobligated funds provided for the Ebola outbreak to USAID for malaria ($250 million) and other global health security ($72.5 million).

|

Agency/Program |

Bush Administration |

Obama Administration |

Trump Administration |

||||||||||||||

|

FY2001-FY2008 Enacted Total |

FY2001-FY2008 Enacted Average |

FY2009-FY2016 Enacted Total |

FY2009-FY2016 Enacted Average |

FY2017 Enacted |

FY2018 Request |

FY2018 Enacted |

FY2019 Request |

||||||||||

|

HIV/AIDS |

918.4 |

114.8 |

891.4 |

111.4 |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

Immunizations |

843.7 |

105.5 |

1,269.7 |

158.7 |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

Polio |

614.5 |

76.8 |

915.9 |

114.5 |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

Other Global/Measles |

229.2 |

28.7 |

353.8 |

44.2 |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

Parasitic Diseases/Malariaa |

0.0 |

0.0 |

142.8 |

17.9 |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

Malaria |

63.4 |

7.9 |

8.0 |

1.0 |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

Global Public Health Protection |

116.5 |

14.6 |

389.2 |

48.7 |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

Global Disease Detection |

103.7 |

13.0 |

310.4 |

38.8 |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

Public Health Capacity |

12.8 |

1.6 |

78.9 |

9.9 |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

CDC Total |

1,942.0 |

242.8 |

2,701.1 |

337.6 |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

NIH Global AIDS Research |

1,935.2 |

241.9 |

3,085.1 |

385.6 |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

HHS Global Fund |

757.3 |

94.7 |

776.1 |

97.0 |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

DOL |

30.3 |

3.8 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

Labor-HHS Total |

4,665.0 |

583.1 |

6,562.3 |

820.3 |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

Ebola Emergency |

0.0 |

0.0 |

1,122.5 |

140.3 |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

Zika Emergency |

0.0 |

0.0 |

377.8 |

47.2 |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

Labor-HHS Total, Including Emergency Appropriations |

4,665.0 |

583.1 |

8,062.6 |

1,007.8 |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

Source: Appropriations legislation, congressional budget justifications, and personal communication with CDC Office of Legislative Affairs.

Acronyms: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), National Institutes of Health (NIH), Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Department of Labor (Labor), not applicable, not specified (n/s).

Notes: Excludes funding for global health through other accounts in State, Foreign Operations appropriations, such as the Economic Support Fund (ESF).

a. In the FY2012 Congressional Budget Justification, the Administration proposed creating a new line item, Parasitic Diseases/Malaria, that combined funding for programs aimed at addressing parasitic diseases (like neglected tropical diseases) with those aimed at combating malaria.

b. The Administration did not request a particular amount for NIH international HIV/AIDS research. Amounts that the Administration spends on NIH international HIV/AIDS research is drawn from the overall budget of the Office of AIDS Research. Those amounts are reported annually in congressional budget justifications.

c. To maintain consistency across fiscal years, CRS did not aggregate the total since FY2018 and FY2019 requested levels for NIH research are not yet available.

|

Agency/Program |

Bush Administration |

Obama Administration |

Trump Administration |

|||||||||

|

FY2001-FY2008 Enacted Total |

FY2001-FY2008 Enacted Average |

FY2009-FY2016 Enacted Total |

FY2009-FY2016 Enacted Average |

FY2017 Enacted |

FY2018 Request |

FY2018 Enacted |

FY2019 Request |

|||||

|

State |

8,663.6 |

1,083.0 |

31,185.2 |

3,898.2 |

4,228.5 |

3,850.0 |

|

|

||||

|

Global Fund |

2,101.1 |

262.6 |

8,600.0 |

1,075.0 |

1,321.4 |

1,125.0 |

|

|

||||

|

USAID |

2,412.7 |

301.6 |

2,459.6 |

307.4 |

323.0 |

0.0 |

|

|

||||

|

SFOPS HIV/AIDS Total |

13,177.4 |

1,647.2 |

42,244.8 |

5,280.6 |

5,873.0 |

4,975.0 |

|

|

||||

|

CDC |

918.4 |

114.8 |

891.4 |

111.4 |

125.5 |

69.5 |

|

|

||||

|

NIHa |

1,935.2 |

241.9 |

3,085.1 |

385.6 |

422.8 |

n/s |

|

|

||||

|

Global Fund |

757.3 |

94.7 |

776.1 |

97.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

|

|

||||

|

DOL |

30.3 |

3.8 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

|

|

||||

|

Labor-HHS HIV/AIDS Total |

3,641.4 |

455.2 |

4,752.6 |

594.1 |

548.2 |

|

|

|||||

|

DOD |

42.1 |

5.3 |

53.2 |

6.6 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

|

|

||||

|

U.S. Global HIV/AIDS Total |

16,860.9 |

2,107.6 |

47,050.6 |

5,881.3 |

6,421.2 |

|

|

|||||

|

Total Global Fund |

2,858.4 |

357.3 |

9,376.1 |

1,172.0 |

1,321.4 |

1,125.0 |

|

|

||||

Source: Appropriations legislation, congressional budget justifications, and personal communication with USAID and CDC legislative affairs offices.

Acronyms: Department of State (State), U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), State, Foreign Operations (SFOPS) appropriations, U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), National Institutes of Health (NIH), Department of Labor (DOL), Departments of Labor, Health and Human Services, and Education (Labor-HHS) appropriations, Department of Defense (DOD), not specified (n/s).

Notes: Excludes funding for global health through other accounts in State, Foreign Operations appropriations, such as the Economic Support Fund (ESF).

a. The Administration did not request a particular amount for NIH international HIV/AIDS research. Amounts that the Administration spends on NIH international HIV/AIDS research is drawn from the overall budget of the Office of AIDS Research. Those amounts are reported annually in congressional budget justifications.

b. To maintain consistency across fiscal years, CRS did not aggregate the total since FY2018 requested levels for NIH research are not yet available.

Table A-5. Global Health Appropriations and Requests: A comparison by Administration

(constant 2018 U.S. $ millions)

|

Bush Administration |

Obama Administration |

|||||||||||

|

FY2008 Enacted |

FY2009 Request |

FY2009R to FY2008E |

FY2009 Enacted |

FY2009R to FY2009E |

FY2016 Enacted |

FY2017 Request |

FY2017R-FY2016E |

FY2017 Enacted |

FY2017R-FY2017E |

|||

|

HIV/AIDS |

141.1 |

139.6 |

-1.5 |

139.9 |

0.2 |

133.8 |

131.2 |

-2.6 |

131.0 |

-0.2 |

||

|

Immunizations |

165.9 |

164.3 |

-1.6 |

168.5 |

4.2 |

228.1 |

223.3 |

-4.8 |

223.3 |

0.0 |

||

|

Polio |

116.3 |

115.1 |

-1.2 |

119.4 |

4.2 |

176.1 |

172.5 |

-3.6 |

172.3 |

-0.1 |

||

|

Other/Measles |

49.6 |

49.2 |

-0.4 |

49.2 |

0.0 |

52.0 |

50.9 |

-1.2 |

51.0 |

0.1 |

||

|

Parasitic Diseases/Measlesa |

10.3 |

10.2 |

-0.1 |

11.1 |

0.8 |

25.6 |

24.9 |

-0.6 |

25.0 |

0.1 |

||

|

Global Public Health Protection |

41.4 |

41.0 |

-0.4 |

55.9 |

14.8 |

57.5 |

78.4 |

20.9 |

56.3 |

-22.1 |

||

|

CDC Total |

358.8 |

355.2 |

-3.6 |

375.3 |

20.1 |

444.9 |

457.8 |

12.8 |

435.6 |

-22.2 |

||

|

HHS Global Fund |

349.9 |

352.9 |

3.0 |

352.9 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

||

|

HHS Appropriations Total |

708.7 |

708.1 |

-0.6 |

728.2 |

20.1 |

444.9 |

457.8 |

12.8 |

435.6 |

-22.2 |

||

|

State HIV/AIDS |

4,885.7 |

5,385.8 |

500.1 |

5,362.3 |

-23.5 |

4,505.8 |

4,413.4 |

-92.4 |

4,413.4 |

0.0 |

||

|

Global Fund |

647.4 |

235.2 |

-412.2 |

823.3 |

588.1 |

1,408.1 |

1,379.2 |

-28.9 |

1,379.2 |

0.0 |

||

|

State Total |

5,533.1 |

5,621.1 |

87.9 |

6,185.6 |

564.6 |

5,913.9 |

5,792.6 |

-121.2 |

5,792.6 |

0.0 |

||

|

HIV/AIDS |

412.1 |

402.3 |

-9.8 |

411.7 |

9.4 |

344.2 |

337.1 |

-7.1 |

337.1 |

0.0 |

||

|

Tuberculosis |

175.7 |

99.4 |

-76.3 |

191.1 |

91.7 |

246.1 |

195.1 |

-51.0 |

246.2 |

51.1 |

||

|

Malaria |

412.1 |

452.8 |

40.8 |

449.9 |

-2.9 |

703.0 |

761.1 |

58.1 |

771.3 |

10.2 |

||

|

Maternal and Child Health |

532.9 |

434.6 |

-98.3 |

517.6 |

83.0 |

782.3 |

832.1 |

49.9 |

832.1 |

0.0 |

||

|

Nutrition |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

64.6 |

64.6 |

130.4 |

110.8 |

-19.5 |

127.7 |

16.9 |

||

|

Vulnerable Children |

17.7 |

11.8 |

-5.9 |

17.6 |

5.9 |

22.9 |

14.8 |

-8.1 |

23.5 |

8.7 |

||

|

Family Planning/Reproductive Health |

472.4 |

354.9 |

-117.5 |

535.2 |

180.3 |

548.4 |

555.8 |

7.4 |

535.3 |

-20.4 |

||

|

Neglected Tropical Diseases |

17.7 |

29.4 |

11.7 |

29.4 |

0.0 |

104.3 |

88.4 |

-15.9 |

102.2 |

13.8 |

||

|

Pandemic Influenza/Other |

136.5 |

58.8 |

-77.7 |

170.5 |

111.7 |

75.6 |

74.1 |

-1.6 |

74.1 |

0.0 |

||

|

USAID Total |

2,177.0 |

1,843.9 |

-333.1 |

2,387.7 |

543.8 |

2,957.2 |

2,969.4 |

12.1 |

3,049.6 |

80.2 |

||

|

SFOPS Appropriations Total |

7.710.1 |

7,465.0 |

-245.1 |

8,573.3 |

1,108.3 |

8,871.1 |

8,7620.0 |

-109.1 |

8,842.2 |

80.2 |

||

|

Total GH Funding |

8,418.8 |

8,173.1 |

-245.7 |

9,301.5 |

1,128.4 |

9,316.0 |

9,219.8 |

-96.3 |

9,277.8 |

58.0 |

||

Sources: Appropriations legislation, congressional budget justifications, and personal communication with USAID and CDC legislative affairs offices.

Notes: Excludes funding for global health through other accounts in State, Foreign Operations appropriations, such as the Economic Support Fund (ESF) and emergency appropriations. "n/s" means not specified.

a. In the FY2012 Congressional Budget Justification, the Administration proposed creating a new line item, Parasitic Diseases/Malaria, that combined funding for programs aimed at addressing parasitic diseases (like neglected tropical diseases) with those aimed at combating malaria. Funding in this row during the Bush Administration includes only malaria spending.

Table A-5. Global Health Appropriations and Requests: A comparison by Administration

(constant 2018 U.S. $ millions)

|

Trump Administration |

|||||||

|

FY2017 Enacted |

FY2018 Request |

FY2017E to FY2018R |

FY2018 Enacted |

FY2018R to FY2018E |

FY2019 Request |

FY2018E to FY2019R |

|

|

HIV/AIDS |

131.0 |

69.5 |

-61.5 |

128.4 |

58.9 |

n/s |

n/s |

|

Immunizations |

223.3 |

206.0 |

-17.3 |

226.0 |

20.0 |

n/s |

n/s |

|

Polio |

172.3 |

165.0 |

-7.3 |

176.0 |

11.0 |

n/s |

n/s |

|

Other/Measles |

51.0 |

41.0 |

-10.0 |

50.0 |

9.0 |

n/s |

n/s |

|

Parasitic Diseases/Measlesa |

25.0 |

24.4 |

-0.6 |

26.0 |

1.6 |

n/s |

n/s |

|

Global Public Health Protection |

56.3 |

50.0 |

-6.3 |

108.2 |

58.2 |

n/s |

n/s |

|

CDC Subtotal |

435.6 |

349.9 |

-85.7 |

488.6 |

138.7 |

400.1 |

-88.5 |

|

HHS Global Fund |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

|

HHS Appropriations Total |

435.6 |

349.9 |

-85.7 |

488.6 |

138.7 |

400.1 |

-88.5 |

|

State HIV/AIDS |

4,413.4 |

3,850.0 |

-563.4 |

4,320.0 |

470.0 |

3,765.8 |

-554.2 |

|

Global Fund |

1,379.2 |

1,125.0 |

-254.2 |

1,350.0 |

225.0 |

904.9 |

-445.1 |

|

State Total |

5,792.6 |

4,975.0 |

-817.6 |

5,670.0 |

695.0 |

4,670.7 |

-999.3 |

|

HIV/AIDS |

337.1 |

0.0 |

-337.1 |

330.0 |

330.0 |

0.0 |

-330.0 |

|

Tuberculosis |

246.2 |

178.4 |

-67.8 |

261.0 |

82.6 |

174.5 |

-86.5 |

|

Malaria |

771.3 |

424.0 |

-347.3 |

755.0 |

331.0 |

659.3 |

-95.7 |

|

Maternal and Child Health |

832.1 |

749.6 |

-82.5 |

829.5 |

79.9 |

606.0 |

-223.5 |

|

Nutrition |

127.7 |

78.5 |

-49.20 |

125.0 |

46.5 |

76.8 |

-48.2 |

|

Vulnerable Children |

23.5 |

0.0 |

-23.5 |

23.0 |

23.0 |

0.0 |

-23.0 |

|

Family Planning/Reproductive Health |

535.3 |

0.0 |

-535.3 |

524.0 |

524.0 |

295.4 |

-228.6 |

|

Neglected Tropical Diseases |

102.2 |

75.0 |

-27.2 |

100.0 |

25.0 |

73.4 |

-26.6 |

|

Pandemic Influenza/Other |

74.1 |

0.0 |

-74.1 |

72.5 |

72.5 |

0.0- |

-72.5 |

|

USAID Total |

3,049.6 |

1,505.5 |

-1,554.1 |

3,020.0 |

1,514.5 |

1,885.3 |

-1,134.7 |

|

SFOPS Appropriations Total |

8,842.2 |

6,480.5 |

-2,361.7 |

8,690.0 |

2,209.5 |

6,556.0 |

-2,134.0 |

|

Total GH Funding |

9,277.8 |

6,830.4 |

-2,447.4 |

9,178.6 |

2,348.2 |

6,956.1 |

2,222.5 |

Sources: Appropriations legislation, congressional budget justifications, and personal communication with USAID and CDC legislative affairs offices.

Notes: Excludes funding for global health through other accounts in State, Foreign Operations appropriations, such as the Economic Support Fund (ESF) and emergency appropriations. "n/s" means not specified.

a. In the FY2012 Congressional Budget Justification, the Administration proposed creating a new line item, Parasitic Diseases/Malaria, that combined funding for programs aimed at addressing parasitic diseases (like neglected tropical diseases) with those aimed at combating malaria. Funding in this row during the Bush Administration includes only malaria spending.