Introduction

History, proximity, commerce, and shared values underpin the relationship between the United States and Canada. Americans and Canadians fought side by side in both World Wars, Korea, and Afghanistan, and continue to collaborate on international political and security matters, such as the campaign against the Islamic State. The countries also share mutual security commitments under the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), cooperate on continental defense through the binational North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD), maintain a close intelligence partnership through the "Five Eyes" group of nations, and coordinate frequently on law enforcement efforts, with a particular focus on securing their shared 5,500-mile border.

Bilateral economic ties, which were already considerable, have deepened markedly over the past three decades as trade relations have been governed by the 1989 U.S.-Canada Free Trade Agreement and, since 1994, by the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). Canada is the second-largest trading partner of the United States, with total two-way cross-border goods and services trade amounting to over $1.6 billion per day in 2017. The United States is also the largest investor in Canada, while Canada is an important source of foreign direct investment in the United States. The countries have a highly integrated energy market, with Canada being the largest supplier of U.S. energy imports and the largest recipient of U.S. energy exports.

Unlike with many countries, whose bilateral relations are conducted solely through foreign ministries, the governments of the United States and Canada have deep relationships, often extending far down the bureaucracy, to address matters of common interest. Initiatives between the provinces and states are also common, such as the 2013 Pacific Coast Action Plan on Climate and Energy among California, Oregon, Washington, and British Columbia, or various initiatives to manage transboundary environmental and water issues.

Nevertheless, bilateral relations have been strained from time to time by individual matters, such as Canada's decision not to participate in the Iraq war in 2003 and the Obama Administration's rejection of the Keystone XL pipeline in 2015. Although the Canadian government welcomed the Trump Administration's March 2017 decision to revive Keystone XL, several other areas of contention have emerged. Canadian officials have been particularly frustrated by the Trump Administration's approach to renegotiating NAFTA and other trade disputes, such as the Administration's decision to impose tariffs on Canadian steel and aluminum. U.S. policy shifts also have affected the opinions of Canadian citizens, 76% of whom disapproved of the "job performance of the leadership of the United States" in 2017.1 This could hinder efforts to conclude bilateral agreements or obtain Canadian support for U.S. initiatives moving forward.

|

"Living next to you is in some ways like sleeping with an elephant. No matter how friendly and even-tempered is the beast, if I can call it that, one is affected by every twitch and grunt." —Pierre Elliott Trudeau, Prime Minister of Canada, 1969. |

With a population and economy one-tenth the size of the United States, Canada has always been sensitive to being swallowed up by its southern neighbor. Whether by repulsing actual attacks from the United States during the War of 1812, or by resisting free trade with the United States for more than the first century of its history, it has sought to chart its own course in the world, yet maintain its historical and political ties to the British Commonwealth. Some in Canada question whether U.S. investment, regulatory cooperation, border harmonization, or other public policy issues cede too much sovereignty to the United States, while others embrace a more North American approach to its neighborly relationship.

Political Situation

Canada is a constitutional monarchy with Queen Elizabeth II as sovereign. In Canadian affairs, she is represented by a Governor-General (since October 2017, Julie Payette), who is appointed on the advice of the prime minister. The Canadian government is a parliamentary democracy with a bicameral Westminster-style Parliament that includes an elected, 338-seat House of Commons and an appointed, 105-seat Senate. Members of Parliament are elected from individual districts ("ridings") under a first-past-the-post system, which only requires a plurality of the vote to win a seat. The party winning the most seats typically is called upon to form a government. A government lasts as long as it can command a parliamentary majority for its policies, for a maximum of four years. Canada's 10 provinces and 3 territories are each governed by a unicameral assembly.

Justin Trudeau was sworn in as Canada's prime minister on November 4, 2015. His Liberal Party won a majority in the House of Commons in October 2015 parliamentary elections, defeating Prime Minister Stephen Harper's Conservative Party, which had held power for nearly a decade. The Liberals' dominant position in the House of Commons has enabled them to implement much of their campaign platform, including measures intended to foster inclusive economic growth, address climate change, and reorient Canada's foreign policy. Nevertheless, Trudeau's approval rating has declined substantially since early 2017 and the Liberal Party is now polling slightly behind the Conservatives. The next federal election is due by October 2019.

2015 Parliamentary Elections

Prime Minister Stephen Harper's Conservative Party entered the 2015 election campaign having governed Canada for nearly a decade. The party first came to power in 2006, just three years after it was established as a result of the unification of the Progressive Conservative party and the Canadian Alliance—a fiscally conservative, western Canadian faction dissatisfied with the eastern tilt of the traditional parties. The Conservatives formed a minority government after the 2006 election, and again after a snap election in 2008, but gained a majority in Parliament in the 2011 election. Harper and the Conservatives campaigned on their management of the economy following the 2008 financial crisis and their enactment of antiterrorism legislation following the 2014 Parliament Hill shootings.2 Many of Harper's initiatives were controversial outside of his political base, however, and the contraction of the Canadian economy during the first half of 2015 as a result of the decline in the price of oil further eroded support for the Conservatives.

Given fatigue with Harper and unease about the economy, many voters reportedly based their decision on which party had the best chance to defeat the Conservatives. The anti-Harper vote was divided primarily between Trudeau's Liberal Party and the New Democratic Party (NDP) led by Thomas Mulcair. The Liberal Party—long known as the "natural party of government" due to its dominance in the 20th century—had its worst showing ever in 2011, when it placed a distant third and was supplanted by the NDP as the main left-of-center party in Parliament. Some analysts even suggested the party could disappear as Canadian politics polarized between the Conservatives and the NDP.3 The election of Trudeau—son of former Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau (1968-1979, 1980-1984)—as party leader helped the Liberals recover some support, but many Canadians perceived the then-43-year-old as lacking experience. Mulcair and the NDP, having served as the Official Opposition, started the campaign in a stronger position and held a slight lead in the polls through the first month of the 11-week campaign. Trudeau gained momentum with better-than-expected debate performances, and outflanked Mulcair on the left with his signature policy proposal to stimulate the economy with three years of deficit spending on new infrastructure and support for the middle class.

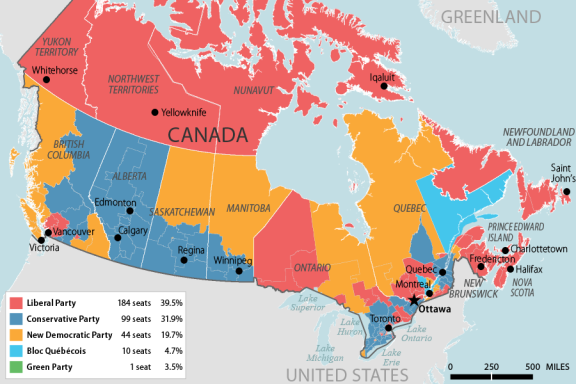

In the end, the Liberals won 184 seats in the House of Commons, up from 34 in 2011, the largest seat gain in Canadian history. In addition to sweeping all 32 seats in the Atlantic Provinces, the Liberal Party dominated in the Toronto metropolitan area, regained its footing in Quebec, won the most seats in British Colombia since 1968, and won two seats in the Conservative stronghold of Calgary (see Figure 1). The Conservatives won 99 seats, down from 166 in 2011, and now serve as the Official Opposition. The NDP won 44 seats, well above its historic average, but a significant decline from the 103 seats it won in 2011. The separatist Bloc Québécois won 10 seats and the Green Party retained a single seat.

|

|

Source: CRS. Data from Elections Canada, "Official Voting Results: Forty Second General Election," 2015. Notes: As of May 2018, the Liberal Party held 183 seats, the Conservatives held 96 seats, the NDP held 43 seats, the Bloc Québécois held 3 seats, and the Green Party held 1 seat. The Groupe Parlementaire Québécois, which broke away from the Bloc, held seven seats, independents held three seats, and two seats were vacant. |

Trudeau Government

The Liberal Party has advanced much of its policy agenda since taking office in November 2015. The Liberals had campaigned on a pledge to improve economic security for the middle class and quickly enacted a fiscal reform that raised taxes on the wealthiest Canadians while reducing them for middle income families. They also created a new child benefit that provides monthly payments to families to help them with the cost of raising children and negotiated with the provinces to gradually increase contributions to the Canada Pension Plan and thereby boost Canadians' pension benefits from one-quarter to one-third of their eligible earnings.4 The Trudeau government's 2018 budget proposal would increase paid parental leave benefits in an attempt to provide more flexibility to families and foster greater gender equality.5

Trudeau and the Liberals also campaigned on a series of political reforms. Most prominently, they pledged that the 2015 election would be the last to be conducted under the first-past-the-post electoral system. Although Trudeau established an all-party committee to examine the issue, he abandoned the electoral reform effort in early 2017.6 The Liberals have followed through on other changes to the political system, including the establishment of a nonpartisan, merit-based process to advise the prime minister on appointments to the Canadian Senate. The change was intended to transform the upper house, which had faced a series of ethics scandals, into a more reputable and collaborative body. Some observers have warned, however, that the growing independence of the unelected Senate could thwart the democratic process.7

On a number of other issues, the Liberals' attempts to balance competing policy priorities appear to have taken a toll on the party's support. For example, Trudeau has worked with Canada's provinces and territories to develop a national climate change plan that imposes a price on carbon emissions while also supporting the construction of new pipelines intended to link Canada's oil sands to overseas markets (see "Climate Change" and "Energy"). The Liberals' approach has drawn criticism from Canadian energy producers and other businesses as well as environmentalists and indigenous groups.8 In the coming months, the Liberals are expected to enact measures to legalize cannabis consumption and amend Canada's antiterrorism legal framework to clarify and expand agencies' authorities, increase transparency and oversight, and enhance civil liberties protections. Although the Liberals have carried out extensive consultations regarding the proposed changes, the tradeoffs involved could disappoint some Canadians who supported the party in the last election.

Trudeau enjoyed high levels of public support during his first year in office, but his approval rating has declined substantially since early 2017, averaging about 41% in recent polls.9 In addition to the policy disagreements discussed above, a series of Liberal Party ethics scandals appear to have tarnished Trudeau's image as someone who would bring a fresh approach to politics.10 In December 2017, for example, Canada's Ethics Commissioner ruled that Trudeau had contravened the country's Conflict of Interest Act by accepting two paid family vacations from a wealthy philanthropist whose foundation had received funding from the Canadian government.11 Trudeau also has begun to face more scrutiny from the political opposition. The Conservative Party elected Andrew Scheer, a 39-year-old Member of Parliament from Saskatchewan, as its new leader in May 2017, and the NDP elected Jagmeet Singh, a 39-year-old former Member of Ontario's Provincial Parliament, as its new leader in October 2017. According to an average of recent polls, 37.2% of Canadians support the Conservatives while 34.8% support the Liberals, 17.4% support the NDP, 6.1% support the Green Party, and 3.4% support the Bloc Québécois.12

Foreign and Security Policy

Canada views a rules-based international order as essential for its physical security and economic prosperity. Historically, the country has sought to promote international peace and stability by leveraging its influence through alliance commitments and multilateral diplomacy.13 Although the Harper government broke with its predecessors to a certain extent, demonstrating more skepticism toward multilateral institutions and a greater willingness to engage in unilateral actions, Trudeau has restored Canada's traditional approach to foreign affairs.14 His government quickly reemphasized multilateral engagement by ratifying the Paris Agreement on climate change and announcing Canada's bid for a temporary seat on the U.N. Security Council for the 2021-2022 term. In June 2017, Canadian Foreign Minister Chrystia Freeland asserted that Canada must set its "own clear and sovereign course" to renew and strengthen the international order given that the United States appeared to be withdrawing from its global leadership role.15 President Trump's actions at the June 2018 Group of Seven (G-7) meeting have reinforced Canadian concerns about the U.S. government's commitment to the rules-based, multilateral system (see text box below).

The Trudeau government also has reaffirmed Canada's support for international security efforts. It unveiled a new defense policy in June 2017, which asserts that as a result of changes in global security dynamics, defending Canada and Canadian interests "not only demands robust domestic defense but also requires active engagement abroad."16 Under the new policy, Canada will increase defense spending by 73% in nominal terms over the next decade from C$18.9 billion (about $14.6 billion) in 2016-17 to C$32.7 billion (about $25.2 billion) in 2026-2027. The additional resources will be used to acquire new aircraft, ships, and other equipment; expand the Canadian Armed Forces by 3,500 personnel; and invest in new capabilities.17

|

The annual G-7 summit of leading industrial democracies (Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States) this year was held in Charlevoix, Quebec, on June 7-8, 2018. Usually placid affairs where leaders reaffirm their commitment to the western alliance, free trade, and international institutions, at this year's summit President Trump criticized the trade policies of the other six nations, as well as their levels of defense spending. The other six nations responded in kind with criticism of the Administration's steel and aluminum tariffs, potential additional tariffs on vehicles, and, implicitly, U.S. climate change policy. As host, Prime Minister Trudeau sought to devote the summit to issues such as promoting inclusive economic growth, combating extreme nationalism, fostering gender equity, and protecting the environment. While initially agreeing on the final communiqué, President Trump withdrew U.S. support after leaving the summit, calling Trudeau "weak and dishonest" after the Prime Minister called U.S. steel and aluminum tariffs "insulting" and vowed reciprocal tariffs. Some of the disagreements included the following:

|

NATO Commitments

Canada, like the United States, was a founding member of NATO in 1949. It maintained a military presence in Western Europe throughout the Cold War in support of the collective defense pact. Since the 1990s, Canada has supported efforts to restructure NATO and has been an active participant in a number of NATO operations, including the 1992 intervention in Bosnia and Herzegovina, the 1999 bombing campaign in Serbia, and the 2011 intervention in Libya. Canada also contributed the fifth-largest national contingent to the NATO-led International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) in Afghanistan, before withdrawing in 2014.

Canada was an advocate for NATO enlargement, and has deployed Canadian Armed Forces personnel to Central and Eastern Europe in support of the newest members of the alliance. In June 2017, Canada took command of a 1,000-strong NATO battle group deployed to Latvia to enhance the alliance's forward presence in Eastern Europe. The battle group includes 450 members of the Canadian Armed Forces, as well as troops from Albania, Italy, Poland, Slovakia, Slovenia, and Spain. The United States, the United Kingdom, and Germany are commanding similar forces in Poland, Estonia, and Lithuania, respectively, as part of a broader effort to reassure the alliance's eastern members and bolster deterrence in the aftermath of Russia's annexation of Crimea and incursion into Ukraine. Canada also has deployed a maritime task force of one frigate to the Eastern Mediterranean to support NATO activities.18

Under the Trudeau government's new defense policy, Canada's total defense spending would reach 1.4% of gross domestic product (GDP) in 2024-2025, which would fall short of NATO's recommended level of at least 2% of GDP. Nevertheless, Canada would exceed NATO's target of investing 20% of defense expenditure in major equipment; such investments would reach 32% of defense spending in 2024-2025.19 Although successive U.S. Administrations have pushed Canada to meet the 2% of GDP target, Canada has long maintained that defense expenditure as a percentage of GDP is not a good measure for determining actual military capabilities or contributions to the NATO alliance.

Participation in Coalition to Combat the Islamic State20

Canada has supported the U.S.-led military campaign against the Islamic State since September 2014. Prime Minister Trudeau followed through on a campaign pledge to "end Canada's combat mission" by withdrawing six CF-18s, which had conducted 251 airstrikes in Iraq and Syria.21 Nevertheless, Canada has continued to support coalition air operations with its refueling and tactical airlift aircraft. Canada is also training, advising, and assisting Iraqi security forces, providing intelligence support to identify Islamic State targets and protect coalition forces, and operating a medical facility that serves as a hub for coalition forces in northern Iraq.22 In June 2017, the Trudeau government announced that Canada would continue to support coalition operations through March 2019, and authorized the deployment of up to 850 Canadian Armed Forces personnel.23

The Trudeau government has sought to complement Canada's military operations with political and humanitarian efforts in the region. It has pledged to provide C$1.6 billion (about $1.2 billion) in security, stabilization, humanitarian, and development assistance over three years to address the crises in Iraq and Syria as well as their impact on Jordan and Lebanon.24 The Trudeau government also has sought to assist those who have been displaced by the conflict, resettling nearly 53,000 Syrian refugees between November 2015 and March 2018.25 Nearly 1,000 Yazidis and other survivors of Islamic State violence were resettled in Canada in 2017.26

U.S.-Canada Defense Relations

According to the U.S. State Department, "U.S. defense arrangements with Canada are more extensive than with any other country."27 There reportedly are more than 800 agreements in place that govern the day-to-day defense relationship.28 The Permanent Joint Board on Defense, established in 1940 by President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Prime Minister Mackenzie King, is the highest-level bilateral defense forum between the United States and Canada. It is composed of senior military and civilian leaders from both countries and provides policy-level consultation and advice on continental defense matters.

NORAD

NORAD is a cornerstone of U.S.-Canadian defense relations. Established in 1958, NORAD originally was intended to monitor and defend North America against Soviet long-range bombers. The NORAD agreement has been reviewed and revised several times, however, to respond to changes in the international security environment. Today, NORAD's mission consists of

- Aerospace Warning: processing, assessing, and disseminating intelligence related to the aerospace domain and detecting, validating, and warning of attacks against North America whether by aircraft, missiles, or space vehicles;

- Aerospace Control: providing surveillance and exercising operational control over U.S. and Canadian airspace; and

- Maritime Warning: processing, assessing, and disseminating intelligence related to the maritime areas and internal waterways of the United States and Canada, and warning of maritime threats to North America to enable response by national commands.

NORAD uses a network of satellites, ground-based radars, and aircraft to fulfill this mission.

NORAD is the only binational command in the world. The U.S. Commander and the Canadian Deputy Commander of NORAD are appointed by, and responsible to, both the U.S. President and the Canadian Prime Minister. Likewise, NORAD headquarters at Peterson Air Force Base in Colorado is composed of integrated staff from both countries. About 300 Canadian Armed Forces personnel are stationed in the United States in support of the NORAD mission, including nearly 150 at NORAD headquarters.29 This binational structure allows the United States and Canada to pool resources, avoiding duplication of some efforts and increasing North America's overall defense capabilities. Nevertheless, since the U.S. and Canadian governments want to maintain their abilities to take unilateral action, some NORAD responsibilities and authorities overlap with those of U.S. Northern Command (NORTHCOM) and Canadian Joint Operations Command (CJOC).

The Permanent Joint Board on Defense reportedly has tasked NORAD with conducting a study on the evolution of North American defense. The study will reportedly examine the air, maritime, cyber, aerospace, outer space, and land threats to North America and the capabilities, command structures, and processes necessary to defeat them.30 Some officials within NORAD reportedly think that NORAD's mission should be expanded to include additional domains, and that NORAD, NORTHCOM, and CJOC should be integrated into a single binational command charged with the defense of the United States and Canada. They maintain that the creation of a unified command and control structure would improve the efficiency and effectiveness of North American defense efforts. Others are opposed to such changes, citing sovereignty concerns and coordination and interoperability challenges.31 During their February 2017 meeting at the White House, President Trump and Prime Minister Trudeau agreed to modernize and broaden the NORAD partnership in the air, maritime, cyber, and space domains.32

Ballistic Missile Defense

Canada has long debated whether it should participate in the U.S. ballistic missile defense system. Facing domestic political opposition and concerns that the system could trigger a new arms race or lead to the militarization of space, Canada opted not to participate in 2005. Some analysts argue that Canada should reconsider its position. They note that Canada has embraced ballistic missile defense as a means of protecting allied countries by signing off on NATO's 2010 Strategic Concept, which endorsed a territorial ballistic missile defense system in Europe. They also note that, contrary to the assumption that the United States would defend Canada in the event of a ballistic missile attack, current U.S. policy is not to use the U.S. ballistic missile defense system on Canada's behalf. Others argue that Canadian participation in the U.S. ballistic missile defense system should be assigned a relatively low priority within Canada's limited defense budget given the need to carry out several large-scale acquisitions to replace core Canadian Armed Forces equipment and systems in the coming years.33

The Trudeau government reexamined Canadian participation in the U.S. ballistic missile defense system as part of its defense policy review, but opted not to pursue a change in policy.34 Although Canada does not participate in the U.S. ballistic missile defense system directly, Canadian personnel, through their participation in NORAD, are involved in the detection of ballistic missiles, and a 2004 agreement permits NORAD to share information with NORTHCOM, which is responsible for the U.S. ballistic missile defense system.35

F-35 Joint Strike Fighter Program36

Canada is one of nine countries that have participated in the U.S.-led F-35 Joint Strike Fighter program since 1997.37 The Canadian government reportedly has invested more than $400 million in the program, and Canadian industry has secured more than $1 billion in contracts as a result of Canada's participation.38 In 2010, the Harper government announced that Canada would acquire 65 Lockheed Martin F-35s to replace the country's aging fleet of 76 CF-18s, which have been flying since the 1980s. The plans became politically controversial, however, amid accusations that the government had misled the public about the cost and performance of the aircraft. In 2012, the Harper government put the procurement process on hold to review the plans and explore alternatives.

During the 2015 electoral campaign, Trudeau vowed to pull out of the F-35 program, open a competitive procurement process for "more affordable" fighters, and invest the savings in the Royal Canadian Navy.39 Nevertheless, the Canadian government has continued to make the annual payments required to remain in the Joint Strike Fighter program and has not ruled out ultimately purchasing the F-35s. Canada's Department of National Defense reportedly expects to open a new competitive process in early 2019.40

Defense Minister Harjit Sajjan has warned that the delay in purchasing the new aircraft could lead to a growing "capability gap" between Canada's NORAD and NATO commitments and the number of fighters available for operations.41 The Trudeau government proposed purchasing 18 new Boeing F/A-18 Super Hornets to supplement the current fleet of CF-18s on an interim basis but reversed the procurement decision after Boeing successfully petitioned the U.S. Department of Commerce to impose antidumping and countervailing duty actions against Bombardier Aircraft of Canada for unfair trade practices in April 2017 (see "Commercial Aircraft"). Instead, Canada opted to purchase 18 used F/A-18s from Australia. Many defense analysts have questioned the decision, noting that the F/A-18s will require costly modifications and maintenance following delivery and lack the capabilities of more modern aircraft, potentially jeopardizing interoperability with the United States and other allies.42

Border Security

The United States and Canada maintain a close intelligence partnership and coordinate frequently on law enforcement efforts, with a particular focus on securing the border since the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks. Under the Beyond the Border declaration, signed in 2011, both nations agreed to negotiate on information sharing and joint threat assessments to develop a common and early understanding of the threat environment; infrastructure investment to accommodate continued growth in legal commercial and passenger traffic; integrated cross-border law enforcement operations; and coordinated steps to strengthen and protect critical infrastructure.43 The declaration led to a 2016 accord to exchange information on individuals who present a clear threat, including the country's respective "no-fly" lists. It also led to other agreements, such as an entry/exit program that was launched in 2013 to allow data on entry to one country to serve as a record of exit from the other and a 2015 agreement to expand preclearance activities to all modes of transport. Implementation of those initiatives has been slow, however, due to Canadian concerns about privacy and sovereignty.

In December 2016, President Obama signed into law the Northern Border Security Review Act (P.L. 114-267), which directed the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) to conduct an analysis of threats along the U.S.-Canadian border. The public summary of the threat analysis, released in July 2017, asserted that "the large volume of legitimate travel across the northern border and the long stretches of difficult terrain between ports of entry provide potential opportunities for individuals who may pose a national security risk to enter the United States undetected."44 The analysis also noted, however, that encounters with individuals associated with transnational crime or terrorism are infrequent and total apprehensions of individuals entering the United States from Canada between points of entry have remained below 800 per year for the past five years. Most of those apprehended have been Canadian citizens. DHS asserts that as a result of actions undertaken as part of the Beyond the Border initiative, Canada has been an effective partner in keeping foreign terrorist suspects from entering North America.45 DHS developed a Northern Border Strategy, released in June 2018, which is intended to address the security challenges identified in the threat analysis while facilitating lawful trade and travel.46

While the number of individuals crossing into the United States from Canada between ports of entry has remained relatively low, the number of individuals crossing from the United States into Canada has grown significantly over the past two years. Nearly 21,000 individuals claimed asylum in Canada after being intercepted between points of entry in 2017.47 The pace of irregular crossings has accelerated this year, with nearly 8,000 individuals encountered from January to April 2018.48 The influx of asylum-seekers reportedly has overwhelmed Canada's refugee processing system, leading the Canadian government to set aside C$173 million (about $134 million) in its latest budget to patrol border crossings and process asylum applications.49 The influx also has strained the resources of aid agencies and local and provincial governments, which are struggling to house and provide social services for the new arrivals.50

This northern flow of asylum-seekers appears to have been spurred, in part, by the Trump Administration's immigration policies, Canada's image as a sanctuary for refugees, and misperceptions about Canada's immigration system. An initial surge occurred after President Trump signed several executive orders related to immigration enforcement in January 2017, and another surge occurred after the Trump Administration indicated in May 2017 that up to 59,000 Haitians with Temporary Protected Status (TPS) would likely lose their protection from removal.51 Although most asylum-seekers who enter Canada through an official border crossing may be returned immediately to the United States under a 2002 "Safe Third Country Agreement," which requires claimants to seek protection in the first safe country in which they arrive, those who enter between ports of entry generally may remain in Canada while their claims are processed.52 The Canadian government reportedly would like to expand the Safe Third Country Agreement to cover the entire border.53 It is facing pressure from Canadian refugee advocates, however, who have called for the agreement to be suspended to allow asylum-seekers to enter Canada in a safer and more orderly fashion.54

Cybersecurity55

Both the United States and Canada rely on information technology as a strategic national asset that reaps many economic and societal benefits. However, increasing reliance on internet-based systems has created new sets of vulnerabilities. Attacks on critical infrastructure and the theft of digitally stored information, either for military or economic competitive advantage, are growing areas of concern for both countries. The Canadian government detected, on average, more than 2,500 state-sponsored cyber activities against its networks from 2013 to 2015.56 In 2014, for example, the Canadian government accused China of carrying out a cyberattack on the National Research Council, which is charged with supporting industrial innovation, advancing technological development, and fulfilling Canadian government mandates. The cost of mitigating the damage reportedly exceeded C$100 million.57 More broadly, the Canadian government blocks 600 million attempts each day to identify or exploit vulnerabilities in its systems and networks.58

Recognizing the scope of the threat and their mutual interests in protecting shared infrastructure, the United States and Canada have integrated cybersecurity into the bilateral agenda. In 2010, the countries put forward the "Canada-United States Action Plan for Critical Infrastructure" intended to establish a comprehensive cross-border approach to prevent, respond to, and recover from critical infrastructure disruptions.59 The 2012 "Cybersecurity Action Plan" between Public Safety Canada and DHS focuses more specifically on enhancing the resiliency of the countries' cyber infrastructure. It is intended to enhance cyber incident management collaboration, improve engagement and information sharing with the private sector, and foster continued collaboration on cybersecurity public awareness efforts.60 The United States and Canada also engage in extensive cybersecurity cooperation through the Five Eyes intelligence alliance, and, as noted above, are exploring the possibility of adding cyber defense to NORAD's mission. In 2012, NORAD and U.S. Northern Command established a Joint Cyber Center to support situational awareness, indications and warning of cyberspace activity, and planning for cyberspace operations.

In its 2018 budget, the Trudeau government proposed investing C$508 million (about $393 million) over five years in cybersecurity efforts.61 The total includes C$155 million (about $120 million) for the country's signals intelligence agency, the Communications Security Establishment (CSE), to create a new Canadian Center for Cyber Security that would consolidate operational cyber expertise from across the federal government. It also includes C$116 million (about $90 million) for the Royal Canadian Mounted Police to create a National Cybercrime Coordination Unit as a hub for cybercrime investigations. The remaining $C237 million (about $183 million) would fund other elements of a new National Cyber Security Strategy that was released in June 2018;62 Canada's previous cybersecurity strategy was adopted in 2010 and was considered dated by many analysts.63 The Trudeau government also has proposed far-reaching changes to Canada's intelligence laws, including provisions that would empower the CSE to engage in offensive cyber operations. Some analysts have expressed concerns that such changes could exacerbate tensions at the core of the CSE's mandate, which requires the agency to simultaneously improve Canada's cybersecurity and defend Canadian information and infrastructure while exploiting vulnerabilities in systems to engage in offensive operations against others.64

Economic and Trade Policy

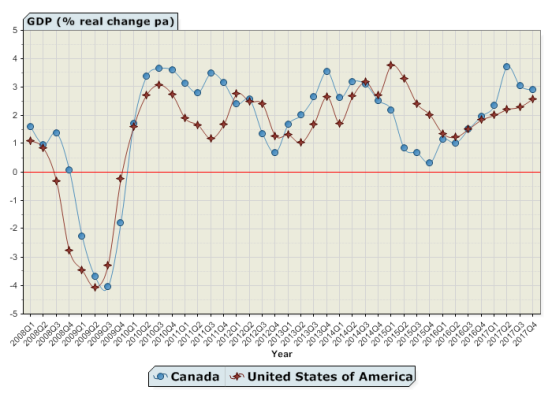

The Canadian economy experienced a shallower recession and initially recovered faster from the 2008 global economic crisis than the United States, but growth in both countries has picked up in recent years. In 2017, the Canadian economic growth outpaced that of the United States: 3.0% in Canada and 2.3% in the United States. In 2018, Economist Intelligence Unit and IHS Global Insight forecasters expect Canada's GDP to grow by 2.0% and 2.4%, respectively, and for U.S. GDP to achieve growth of 2.0% and 2.7%.65 The Canadian economy disproportionately depends on the global market for exporting commodities; however, in recent years growth has been dependent on personal consumption, especially in the still-buoyant housing sector. In Canada, the unemployment rate, which hit a generational low of 5.8% in January 2008, peaked at 8.7% in August 2009, but gradually has fallen back to a cycle low of 6.3% in April 2018.

|

Figure 2. United States and Canada Real Gross Domestic Product (GDP): 2008-2017 real percentage change quarterly |

|

|

Source: Economist Intelligence Unit, Country Data Tool. |

Budget Policy

After racking up 27 straight years of deficit spending prior to the "austerity" budget of 1995, Canada's public debt reached a peak of 101.6% of GDP and government sector spending reached 53.6% of GDP in 1993. Realizing this course was unsustainable, the Liberal government of then-Prime Minister Jean Chrétien and his Finance Minister Paul Martin embarked on a financial austerity plan in 1995 using such politically risky measures as cutting federal funding for health and education transfers, applying a means test to those eligible for Seniors Benefits, and cuts in defense. Modest tax increases were also employed, mostly through closing loopholes. Under this budget discipline, the government submitted a balanced budget in 1998 and a political consensus emerged not to resort to deficit spending. However, in the face of the global financial crisis in 2009, the Conservative government of Prime Minister Stephen Harper introduced a budget package of stimulus spending and tax cuts, producing a fiscal deficit for the first time in a decade.

From 2009 to 2015, the Conservative government ran deficits; the deficit reached 5% of GDP in 2010, but through austerity and improved economic conditions was steadily whittled down to 1.9% of GDP by 2015. The Harper government sought to return Canada to fiscal balance by the 2015 election, resorting to certain one-off savings, such as selling embassies and liquidating (literally) gold coins found in the Bank of Canada vaults.66 Ultimately, a sluggish economy thwarted those plans and the last Harper budget in 2015 left a C$3 billion (about $2.3 billion) deficit.67

|

Indicator |

United States |

Canada |

|

|

GDP Nominal PPP (billion US$) Nominal (billion US$) |

19,391 19,391 |

1,702 1,652 |

|

|

Per Capita GDP Nominal PPP (US$) |

59,390 |

46,470 |

|

|

Real GDP Growth |

2.3% |

3.0% |

|

|

Recorded Unemployment Rate |

4.4% |

6.3% |

|

|

Exports G&S(%GDP) (2016) Imports G&S (%GDP) (2016) |

11.9% 14.7% |

31.0% 33.4% |

|

|

Sectoral Components of GDP (%) Industry Services Agriculture |

18.9% 80.1% 0.9% |

28.2% 70.2% 1.6% |

|

|

Current Account Balance (% GDP) |

-2.4% |

-3.0% |

|

|

Public Debt/GDP |

77.4% |

98.2% |

|

|

Average MFN Tariff (2016) |

3.5% |

4.1% |

|

Sources: Economist Intelligence Unit; U.S. Census Bureau; Bureau of Economic Analysis; Statistics Canada; World Bank.

During the 2015 election, Justin Trudeau upended Canadian political orthodoxy by campaigning on a targeted budget deficit—C$10 billion (about $7.7 billion) a year for three years—for infrastructure projects to stimulate a sluggish economy reeling from the commodity and energy price collapse at mid-decade. This electoral gambit paid off at the polls, but economists forecast a larger deficit than the government had included in its election manifesto.

The first budget of the Trudeau government was introduced on March 22, 2016, with the theme of "growing the middle class." It featured a pledge to invest C$120 billion (about $92.3 billion) over the next 10 years, divided into a short-term pledge of C$11.9 billion (about $9.2 billion) during the life of the Parliament to upgrade and improve public transport systems, water, wastewater, green infrastructure projects, and affordable housing. The second phase is to include broad measures to reduce urban congestion, expand trade corridors, and launch a low-carbon national energy system. It provided additional funds for indigenous communities, a consolidation of child and family tax benefits, new cultural and arts funding, and a "revitalization" of the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC). Funds will also be available to finance an "innovation agenda," including increased fundamental research and a "Post-Secondary Institutions Strategic Investment Fund" to promote on-campus research, commercialization opportunities, and training facilities for the nation's universities.68 As noted above, the government is funding these measures through additional deficits estimated by the government to be C$113.2 billion through FY2021, using a relatively conservative 0.4% annual growth estimate. It also seeks to offset some of this increased spending through a 4% increase in the top tax rate (from 29% to 33%) and a reduction in the annual tax-free savings account (TFSA) contribution from C$10,000 to C$5,500. Partly offsetting this, however, is a reduction of the second-lowest tax bracket from 22% to 20.5%.

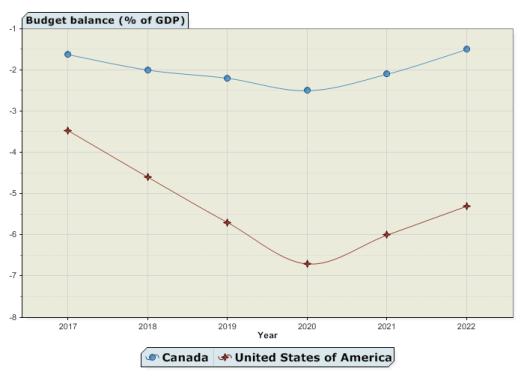

|

Figure 3. Projected Budget Deficits: United States and Canada: 2017-2022 budget deficits as a percentage of GDP |

|

|

Source: Economist Intelligence Unit. |

The 2018 budget was released on February 27, 2018. It totaled C$311.3 billion ($242.8 billion that day), with a deficit of C$17.8 ($13.9 billion that day). Gender equity was the theme for the 2018 budget; gender was reportedly mentioned 358 times.69 Highlights include

- pay-equity legislation for employees in the federal government and federal-regulated sectors;

- incentive for new fathers to take parental leave;

- a new Indigenous Skills and Employment Training Program designed to help close the pay and employment gap between indigenous and nonindigenous;

- revamped low-income tax credit for low-income workers;

- funding for fundamental scientific research, government labs, and a reinvigoration of the national research council; and

- a new Canadian Centre for Cybersecurity and a National Cybercrime Coordination Unit for the RCMP.

Monetary Policy

Since the global financial crisis, United States and Canada have maintained an accommodative monetary policy. Early on, however, the Bank of Canada (BOC) raised its benchmark overnight interest rates three times—to a 1% target rate to constrain demand—until September 2010. It kept its rate at 1% until 2015, when it lowered it twice, by 25 basis points in January and July to 0.5%. BOC raised the key rate twice in 2017 and once (thus far) in 2018 to the current rate of 1.25%. This accommodative stance has been made possible by the virtual absence of inflation, but it has also contributed to the housing and personal consumption booms that have continued since the financial crisis. This, in turn, has led to record Canadian household indebtedness with the debt-to-disposable-income ratio reaching 170% in 2015, compared to 111% in the United States.70

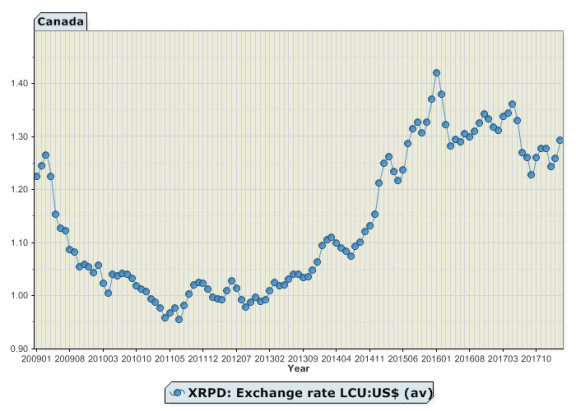

The value of the Canadian dollar (or loonie, its nickname) has varied in terms of the U.S. dollar in recent years (see Figure 4). Prior to the financial crisis, the Canadian dollar had been nearly at parity, trading at slightly less than the U.S. dollar. During the financial crisis it dropped to a monthly average of C$1.26/US$1. As the economy stabilized and demand for commodities and energy resumed, the Canadian dollar appreciated to C$0.96/US$1 in July 2011. As oil prices dropped and the commodity boom ended, the Canadian dollar began depreciating, its decline accelerating with the reduction of interest rates from 1.0% to 0.5% in 2015. The Canadian dollar hit a low of C$1.42/US$1 in January 2016. The currency has since rebounded with higher interest rates and has remained in the C$1.30-1.20/$1.00 range in the 2017-2018 period.

The strength of the Canadian dollar roughly from 2002 to 2008 and 2010 to 2013 had a detrimental effect on Canadian manufacturing, as export-dependent goods became relatively uncompetitive in world markets. The Canadian auto industry was especially hard hit as the center of gravity of U.S. production has moved south, and new North American investment has bypassed Canada for the United States and, especially, Mexico.71 Since the end of the commodities boom, the loonie has depreciated and manufacturing has picked up, but, like with the United States, it represents a declining share of GDP.

U.S.-Canada Trade Relations

The United States and Canada enjoy one of the largest bilateral commercial relationships in the world. Over the past 30 years, U.S.-Canada trade relations have been governed first by the 1989 U.S.-Canada Free Trade Agreement and, subsequently, by the 1994 North American Free Trade Agreement. The two countries were leaders in the creation of the open, rules-based multilateral trading system characterized by mutual concessions on market access for goods and services, disciplines on trade restrictions and binding dispute settlement mechanisms. Both countries were founding members of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, the genesis of the postwar multilateral trading system, and in 1994 were founding members of the World Trade Organization. Now, however, the unilateral tariff measures imposed by the Trump Administration, its withdrawal from the Trans-Pacific Partnership regional trade agreement, and its skepticism of multilateralism have called this system into question. Regionally, the Trump Administration has engaged Canada and Mexico to negotiate revisions to the nearly 25-year-old North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA).

The volume of economic activity across the border underscores the extent of economic integration between the United States and Canada. The two nations continue to have one of the largest trading relationships in the world, with $1.6 billion per day in goods crossing the border in 2017. However, in 2015, China overtook Canada as the largest trading partner of the United States. Canada is the largest country destination for U.S. exports, although China replaced Canada as the largest supplier of imports to the United States in 2007 and Mexico surpassed Canada in 2015.

In 2017, Canada was the largest purchaser of U.S. goods at 18.3% of U.S. goods exports. Canada was the third-largest supplier of U.S. imports at 12.8% of all U.S. goods imports. The United States is Canada's largest goods export destination and import supplier. In 2017, the United States supplied 53.3% of Canada's imports of goods and purchased 75.9% of Canada's merchandise exports. Two-way trade with the United States represented nearly 32% of Canadian GDP that year.

|

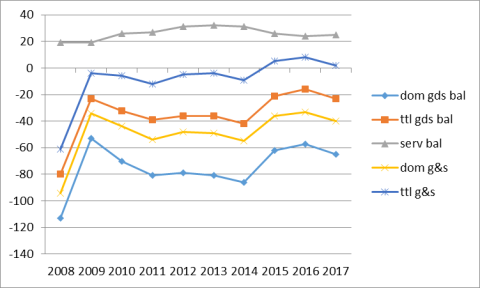

U.S. Trade Balance with Canada: Deficit or Surplus? President Trump has made the reduction of bilateral trade deficits the centerpiece of his trade policy. While most economists believe that trade deficits are more the result of macroeconomic factors such as savings and investment imbalances, President Trump has criticized countries that run a trade surplus with the United States. Canada is no exception, with the President claiming large trade deficits with the northern neighbor, blaming NAFTA for the imbalance. Meanwhile, Canada claims that it has a trade deficit with the United States. So who is correct? The answer, as with much in economics, lies with how it is counted. The United States compiles goods-trade statistics in two ways. The metric that captures the broadest amount of trade is the general import/total export measure. This measures all goods coming into to the country (general imports) and all goods leaving (total exports). This measure captures all goods that cross the border either produced in the country or transhipped through its ports to another country without further processing. In terms of Canada-U.S. trade, this metric traditionally has shown a smaller deficit. According to the general import/total export measure, the United States had a deficit of $22.7 billion with Canada in 2017. Alternatively, the import for consumption/domestic export metric only measures goods consumed or produced in the United States. This figure traditionally has shown a wider deficit, comprising a $64.8 billion deficit with Canada in 2017. The foregoing discussion has only concerned goods trade. The United States has had a consistent services surplus with Canada amounting to $25.4 billion in 2017. If combined with the general imports/total exports goods metric, the United States had a goods and services trade surplus of $2.8 billion with Canada in 2017; if combined with the narrower imports for consumption/domestic exports metric, goods and services trade with Canada showed a deficit of $39.4 billion (see Figure 5).72 |

U.S.-Canada trade relations have taken on a different tone during the Trump Administration. Whether it has been the reemergence of old irritants such as trade in softwood lumber and dairy restrictions, new disputes such as commercial aviation, or the contentious NAFTA negotiations, the commercial relationship between the two nations is facing new challenges. President Trump commented on the various trade disputes in a June 2018 tweet (see text box).

|

"Canada has treated our Agricultural business and Farmers very poorly for a very long period of time. Highly restrictive on Trade! They must open their markets and take down their trade barriers! They report a really high surplus on trade with us. Do Timber & Lumber in U.S.?" —President Donald Trump on Twitter, June 1, 2018 |

NAFTA Renegotiation

On May 18, 2017, the Trump Administration sent notification to Congress of its intent to begin talks with Canada and Mexico to renegotiate NAFTA.73 Following the 90-day consultation period with Congress mandated under trade promotion authority, negotiations began on August 16, 2017. Initially, much of the discussion revolved around revising and modernizing the nearly 25-year-old accord. All three parties alluded to incorporating new or expanded language from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) negotiations on e-commerce, intellectual property rights, investment, labor, environment, sanitary and phytosanitary standards, state-owned enterprises, data flows, and data localization—requirements to maintain data in country. A goal to conclude the talks by March 31, 2018, was not met; nor has a goal to conclude the talks by the end of May 2018, potentially allowing for consideration in the current session of Congress, been met. The imposition of tariffs on steel and aluminum from Canada and Mexico (see "Steel and Aluminum Tariffs") may have further dampened momentum for an agreement.

At times, President Trump has threatened to withdraw from NAFTA. The Administration has also tabled some proposals that are considered unacceptable or unworkable by Canada and Mexico and have become sticking points in the negotiations. The overall gist of U.S. proposals appears to be aimed at reducing the bilateral trade deficits with Canada and Mexico and returning manufacturing jobs to the United States. If those goals are not achievable, they may be used as a pretense to withdraw from the talks. Economists, in general, contend that trade deficits and job creation are more a function of macroeconomic conditions and not of free trade agreements (FTAs). On most issues, the negotiating dynamic generally has pitted the United States against Canada and Mexico, which are more interested in modernizing the agreement and oppose proposals that would restrict trade.

President Trump reportedly also favors negotiating separate deals with Canada and Mexico. On June 5, 2018, Larry Kudlow, an economic adviser to the President, restated the President's support for negotiating bilateral deals. According to Kudlow, "When you have to compromise with a whole bunch of countries, you get the worst of the deals. Why not get the best? ... Canada is a whole lot different from Mexico."74 In the past, Canada and Mexico have opposed negotiating separate agreements.

Sunset Clause. The United States has proposed that a revised NAFTA expire after five years, unless affirmed by all parties. According to the Administration, this would ensure that the agreement would continue to work for all parties. This proposal is opposed by Canada and Mexico, which claim that it would adversely affect investor confidence and long-term investment in the region. On May 31, 2018, Prime Minister Trudeau stated that Vice President Pence told him that the sunset clause was a precondition for a possible summit to conclude a deal. Trudeau reportedly told Pence that "there was no possibility of any Canadian prime minister signing a NAFTA deal that included a five-year sunset clause."75

Rules of Origin (ROO). Automotive rules of origin have become a major sticking point in the negotiations. ROOs play an important part in determining the supply chain for a product, and, over the years, NAFTA has created an integrated North American supply chain for vehicles. The United States originally proposed to increase to 85% the current rules of origin of 62.5% for cars, light trucks, engines, and transmissions, and to 60% for parts, and to introduce a 50% U.S. domestic content requirement. The latter has been a point of contention with Canada and Mexico since NAFTA does not distinguish between U.S. and North American content. U.S. auto companies fear that these additional content requirements threaten to disrupt their supply chains.76 The United States reportedly has scaled back its original proposal now to require 75% regional content on NAFTA cars, and a three-tiered ROO on components of 75% for critical components such as engines and transmissions, and 70% and 65% for other components.77 The United States reportedly also replaced its domestic content proposal with a content demand tied to wages; 40% of a car and 45% of a truck would be made by workers making $16 an hour.78 In addition, the U.S. proposal would require 70% of a vehicle to be manufactured with North American steel and aluminum. Mexico has thus far rejected tying wages to ROO levels. Canada has not publicly commented, but the proposal has been seen in some quarters as a way of attracting Canadian support, as Canadian auto wages are comparable with those of the United States and Canada may stand to gain from the proposal.

Government Procurement. The Trump Administration has promoted "Buy American, Hire American" policies and seeks greater restrictions on the ability of Canadian and Mexican firms to access the U.S. procurement market. The U.S. proposal reportedly would cap procurement access to the U.S. market at the dollar value of procurement access available in Canada and Mexico.79 Given that the procurement markets in Canada and Mexico are substantially smaller than that of the United States, this proposal, in effect, would reduce the amount of procurement available to be bid on by Canadian and Mexican firms. The United States is also seeking to exclude state and local government procurement from NAFTA, as it did in the TPP. Meanwhile, Canada has been dissatisfied with the application of Buy American policies, especially their exclusion from so-called "pass-through" government procurements—state-tendered contracts using federal funds. It seeks greater procurement opportunities, claiming that the integrated cross-border supply chain that NAFTA has created would be negatively affected by additional buy-local policies.80

Chapter 19 Dispute Settlement. The United States is seeking to disband the binational dispute settlement mechanism that provides disciplines for settling disputes arising from a NAFTA party's statutory amendment of its antidumping (AD) or countervailing duty (CVD) laws, or as a result of a NAFTA party's AD or CVD final determination on the goods of an exporting NAFTA party. Chapter 19 provides for binational panel review of final determinations in AD/CVD investigations conducted by NAFTA parties in lieu of judicial review in domestic courts. This provision was placed in NAFTA at Canada's insistence, and Canada reportedly considers removing it a red line.81

Dairy. Canada administers a restrictive supply management system for dairy, poultry, and eggs, a program that was specifically excluded from NAFTA (see box below). The Trump Administration seeks to have Canada dismantle the system, while Canada has pledged to uphold the system. Previous agreements Canada has entered into, such as the TPP, have allowed for greater market access without dismantling the system. For its part, Canada maintains that any discussion on supply management should include U.S. dairy subsidies as well. U.S. dairy producers are also concerned about restrictions on exports of ultra-filtered milk. This high-protein product, not developed at the time of NAFTA, and with no tariff line attached to it, has been one of the only dairy products freely exported into Canada. However, a new Canadian ingredient pricing strategy has imperiled that access by incentivizing Canadian dairy product processors to use domestic ingredients over imported.82

|

Supply Management for Dairy, Poultry, and Eggs Canada uses supply management to support its dairy, poultry, and egg sectors. Its main features (1) provide price support to producers based on their production costs and return on equity and management, (2) limit production to meet domestic demand at the cost-determined price, and (3) restrict imports to protect against foreign competition. The Canadian government has supported producers' decisions to use this approach for more than 40 years, and succeeded in limiting imports of these products in negotiating the U.S.-Canada Free Trade Agreement, NAFTA, its multilateral commitments in the Uruguay Round's Agreement on Agriculture, and for the most part in its bilateral free trade agreements. National bodies and provincial commodity marketing boards, granted statutory powers by the federal and provincial governments, control the supply management systems for these commodities. At the national level, the amount of each commodity that producers can market is controlled by a quota system. Imports of each commodity are limited by tariff rate quotas. These allow a specified amount to enter annually under Canada's trade commitments at little or zero duty, but apply a very high tariff (over 200% in many cases) on imports above the specified level or quota amount. Both tools work together to control the supply of each commodity, but the objective is to ensure that producers receive a price that guarantees them a return that covers their production costs. The quota is set to balance supply with demand at that price, and is frequently adjusted to ensure that this balance is achieved. Producers of these commodities must participate in their respective supply management systems, with farm-level production subject to individual quota limits that can only be sold into permitted marketing channels. Producers of these commodities point out the benefits of the supply management approach, which they say has significantly reduced price volatility. The stability of prices over time, combined with the guarantee that covers production costs, has served to provide income support. Others point out that these features have resulted in the lack of market orientation for these commodities, as the value of supply management has become capitalized, or incorporated, into the value of the quota. In other words, those who hold quota (i.e., renting it out) benefit more than the producers themselves. Conversely, consumers end up paying more for these products, and some Canadians near the border cross over to the United States for their milk and egg runs. |

Investment. The Trump Administration reportedly favors scrapping the controversial investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS) mechanism in the investment chapter of the agreement. NAFTA was the first U.S. FTA to include an investment chapter, modeled after U.S. bilateral investment treaties. ISDS is a form of binding arbitration that allows private investors to pursue claims against sovereign nations for alleged violations of the investment provisions in trade agreements. The United States reportedly has proposed to make ISDS an opt-in, opt-out system, with each party determining whether to accept cases from the other. The United States reportedly also has proposed to limit eligibility to claims involving direct expropriation. Complainants could no longer seek arbitration for indirect expropriation—enactment of laws or regulations that compromise the value of the investment.

Given the reported U.S. desire to opt out of ISDS, Canadian negotiators reportedly have proposed to eliminate ISDS provisions altogether or to maintain them only with Mexico if the United States opts out.83 The U.S. business community strongly opposes U.S. proposals to scale back or eliminate the ISDS provisions, while U.S. labor and civil society groups have welcomed the Administration's more skeptical approach to ISDS. United States Trade Representative (USTR) Robert E. Lighthizer reportedly maintains that ISDS incentivizes outsourcing.84 The 2015 TPA called for "providing meaningful procedures for resolving investment disputes," which may affect congressional consideration of an agreement.85 In a March 20, 2018, letter to USTR Lighthizer, over 100 Members of Congress "insist that ISDS provisions at least as strong as those contained in the existing NAFTA must be included in a modernized agreement to win Congressional support."86 Other Members of Congress who oppose ISDS presumably would welcome the move.

Softwood Lumber

Trade in softwood lumber traditionally has been one of the most controversial topics in the U.S.-Canada trading relationship, which is now in its fifth iteration of litigation. The dispute revolves around different pricing policies and forest management structures in Canada and the United States. In Canada, most forests are owned by the Canadian provinces as Crown lands, whereas in the United States, most forests are privately held. The provinces allocate timber to producers under long-term tenure agreements, and charge a "stumpage fee," which U.S. producers maintain is not determined by market forces, but rather acts as a subsidy to promote the Canadian industry, sectoral employment, or regional development. Canada denies that its timber management practices constitute a subsidy, and maintains that it has a comparative advantage in timber and a more efficient industry.

Until October 2015, trade in softwood lumber was governed by a seven-year agreement (SLA)—reached in 2006 and since extended for two years to 2015—restricting Canadian exports to the United States. As part of a complicated formula, the United States allowed unlimited imports of Canadian timber when market prices remained above a specified level; when prices fell below that level, Canada imposed export taxes and/or quotas. In addition, the United States returned to Canada a large majority of the duties it had collected from previous trade remedy cases.

The current dispute (Lumber V) started when the 2006 Softwood Lumber Agreement (SLA) expired. After a year-long grace period, a coalition of U.S. lumber producers filed trade remedy petitions on November 25, 2016, which claimed that Canadian firms dump lumber in the U.S. market and that Canadian provincial forestry policies subsidize Canadian lumber production. These petitions subsequently were accepted by the two agencies that administer the trade remedy process: the International Trade Commission (ITC) and the International Trade Administration (ITA).

On December 7, 2017, the ITC determined that imports of softwood lumber, previously determined to be dumped and subsidized by ITA, caused material injury to U.S. producers. This means that ITA's final duties in the antidumping (AD) and countervailing duty (CVD) proceedings, announced on November 2, 2017, can be imposed on affected Canadian lumber. ITA found subsidization of the Canadian industry and determined a subsidy margin of 3.34%-18.19% on Canadian lumber, depending on the firm. ITA found dumping margins of 3.20% to 8.89%, also firm dependent. The AD and CVD duties were imposed on January 3, 2018. Canada is challenging these trade remedy decisions at World Trade Organization and NAFTA Chapter 19 tribunals.

Steel and Aluminum Tariffs

On March 8, 2018, President Trump signed proclamations imposing tariffs on steel (25%) and aluminum (10%) under Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962, as amended, after the Commerce Department determined that current imports threaten national security. Canada and Mexico initially were excluded from the tariffs as an "incentive" to a favorable conclusion to the NAFTA negotiations, with the President indicating that the tariffs "will only come off if [a] new and fair NAFTA agreement is signed."87 The tariffs were scheduled to come into effect on May 1, but were delayed until June 1 to give negotiators more time. Both Canada and Mexico have rejected the linkage, and Canada maintains that, as a part of the U.S. defense industrial base and a NATO treaty ally, it should be excluded on national security grounds.88 Canada is the largest source of U.S. raw iron and steel imports at 19%; however, when combined with articles of manufactured steel products (sheet, pipe, etc.), the Canadian share of all steel imports falls to 14%, behind China at 18.8%. Total U.S. imports of steel and steel products amounted to $9.1 billion in 2017. Canada is also the largest source for U.S. imports of aluminum. Totaling $7.4 billion, Canadian imports represent 44% of U.S. aluminum imports.

|

"These tariffs are an affront to the longstanding security partnership between Canada and the United States, and, in particular, to the thousands of Canadians who have fought and died alongside American comrades in arms." —Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, May 31, 2018 |

On May 31, 2018, Canada announced retaliatory tariffs of $12.8 billion to begin on July 1, 2018. U.S. steel and steel products are to face a tariff of 25%; U.S. aluminum and a host of other U.S. consumer products are to face 10% tariffs.89 The Canadian tariffs have been targeted to extract maximum political cost. Canada disputes the national security basis of the tariffs, noting Canada's long-standing military ties with the United States and its role as a secure supplier for the U.S. defense industrial base (see text box). Canada has also sought consultation with the United States at the WTO—the first step in filing a dispute settlement case—and sought recourse under NAFTA Chapter 20 dispute settlement.90

If these tariffs continue, it could lead to greater production and higher employment in those industries the United States. However, because it likely would lead to higher prices for those products, it may lead to decreased sales and employment in downstream industries that use those products, such as vehicles, aircraft, or durable goods. In the longer term, it could result in additional downstream production in other countries, including Canada for vehicles, as vehicles produced with steel and aluminum in those countries would not be subject to the tariffs, at least as long as NAFTA remains in effect.

Commercial Aircraft

On April 27, 2017, Boeing filed AD/CVD actions against Bombardier Aircraft of Canada. In its petition, it charges that Bombardier received extensive launch aid from the Canadian government and a $2.5 billion bailout by the Quebec government in 2015, and that its planes are sold in the United States at below market prices, unfairly competing with a new class of Boeing 737-700 mid-range aircraft. While Commerce determined an antidumping rate of 79.82% and a countervailable subsidy rate of 212.39%, the ITC found the planes do not injure U.S. industry and the proceedings were terminated on January 26, 2018. Before the ITC finding was released, Bombardier partnered with Airbus primarily to make the planes at the latter's facility in Alabama to avoid the tariffs, and the Canadian government cancelled its planned procurement of Boeing CF-18 Super Hornet fighter jets.

Intellectual Property Rights (IPR)

In 2018, the U.S. Trade Representative downgraded Canada on its Special 301 report on intellectual property rights (IPR) protections to a "priority watch list" country for inadequate IPR protection and enforcement. Canada had been on the "watch list" since 2013. That year Canada enacted its Copyright Modernization Act, which implemented the World Intellectual Property Organization's Copyright treaty and Performance and Phonograms treaties.91 The act is analogous to the U.S. Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA, P.L. 105-304). The act allows for some format shifting (right to copy/back-up for private purposes) and fair-dealing (fair-use) exceptions for legitimate purposes (e.g., news, teaching, and research), but prohibits the circumvention of digital protection measures. It also clarified the rights and responsibilities of internet service providers for infringement of their subscribers, and provides for a "notice-and-notice system" to warn potential infringers.

Canada has also taken steps to address counterfeit products through enacting the Combating Counterfeit Products Act and implementing it in January 2015. Among other provisions, the act provides Canadian customs officials "ex officio" authority to seize pirated and counterfeit goods without a court order. However, it does not provide this authority for goods in transit, about which the Special 301 report notes the United States remains "deeply concerned."

In June 2017, the Supreme Court of Canada (SCC) invalidated the "promise doctrine", which was a utility requirement used by Canadian courts to assess the validity of a patent. The "promise" of the doctrine referred to the expectation that the patent holder fully demonstrate the usefulness of the patent at the time of the filing date. In the words of the SCC:

The Promise Doctrine risks, as was the case here, for an otherwise useful invention to be deprived of patent protection because not every promised use was sufficiently demonstrated or soundly predicted by the filing date. Such a consequence is antagonistic to the bargain on which patent law is based wherein we ask inventors to give fulsome disclosure in exchange for a limited monopoly.

The doctrine reportedly has led to the invalidation of 25 patents since 2005.92 U.S. pharmaceutical companies argued that the use of the doctrine, which can lead to an invalidation of patents on utility grounds years after the patent has been granted, has contributed to an uncertain business environment in Canada. Eli Lilly, a U.S. pharmaceutical company, took Canada to arbitration under NAFTA's Chapter 11 investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS) mechanism. The case stemmed from the invalidation of patents for two of Eli Lilly's drugs under the promise doctrine; however, the ISDS panel ruled in favor of Canada, as the drug company was unable to prove that an expropriation occurred.93

As a result of the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA), Canada's FTA with the European Union, Canada revamped its regulations on patent term restoration and patent linkage. Canada will provide two years of a patent term restoration if marketing authorization takes longer than five years from the filing of a basic patent. The additional patent protection applies only to the pharmaceutical product covered by the marketing authorization, not by subsequent modifications of uses, methods, or processes. In the 2018 Special 301 report, USTR called the changes "disappointingly limited in duration, eligibility, and scope of protection."94

Canada also changed its patent linkage system to comply with CETA. Under the Patent Medicines (Notice of Compliance) [PMNOC] regulations, a generic drug maker could seek marketing approval by challenging the validity of the patent and claiming noninfringement. It allowed a patent owner to apply to federal court to keep a generic company's potentially infringing medicine off the market. However, the burden of proof was on the patent holder, and if the appeal was unsuccessful, the NOC was issued, rendering moot any further challenge to the authorization. A patent holder could start again by launching a patent infringement lawsuit, with the resultant duplication of effort. As of September 21, 2017, Canada replaced that system with a single-track process resulting in final determinations of patent infringement and validity, providing both sides with equivalent rights of appeal.95

Despite these changes, the 2018 Special 301 report returned Canada to "priority watch list" status due to what USTR contends is "a failure to resolve longstanding deficiencies in protection and enforcement of IP." According to USTR, the policies of concern include

- weak enforcement of copyright and piracy infringement, noting that no known copyright prosecutions occurred in Canada in 2017;

- discretion of the Health Minister in disclosing confidential business information;

- an education-related exception to copyright that USTR views as ambiguous and claims has damaged the market for educational publishers and authors;

- failure to provide full and fair national treatment with respect to copyrights; and

- lack of due process and transparency in its geographical indications protections. This has been an issue with regard to the additional commitments made by Canada in its FTA with the European Union, which USTR claims negatively affect market access for U.S. agricultural producers.96

These issues present challenges for bilateral trade relations, given the highly integrated nature of supply chains and other factors. Securing strong IP provisions is a priority for the United States in the ongoing NAFTA renegotiation and modernization effort.

|

FATCA and Canada The Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act (FATCA) (P.L. 111-147) was enacted in 2010 with the aim of curtailing tax evasion and money laundering, and it was implemented in 2014. However, for U.S. citizens or dual-national citizens living in Canada—some considered to be "accidental Americans" because they were born in the United States or have American parentage—the law is having unintended consequences. In addition, some Members of Congress are seeking its repeal.97 Among its provisions, FATCA institutes a 30% withholding tax to foreign financial institutions unless some reporting requirements are met. Foreign financial institutions are to provide specific details on U.S. beneficial owners. In addition, individuals required to file a Foreign Bank and Financial Account Report (FBAR) are required to report the information on tax returns if the value of the account is $50,000 or more. The penalty for nondisclosure of such information was raised from 20% to 40% for each transaction. In response to this law, Canada, among other nations, signed an intergovernmental agreement (IGA) to require banks to give information about U.S.-related accounts to the Canadian Revenue Agency (CRA), which would vet the information, and would then provide that information to U.S. authorities. Under the Common Reporting Standard, developed by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Canada itself is beginning to share bank information among 50 countries that have signed on to it as of May 2018. Canada has streamlined both requirements into a single-track Enhanced Financial Account Information Reporting system.98 FATCA affects what the IRS considers "U.S. persons," which includes U.S. citizens living abroad or dual-nationals. FATCA and the IGA implementing Canadian compliance with the information-sharing requirements are controversial in Canada. Some Canadians have voiced privacy concerns. It was reported that 31,574 records were transferred directly to the U.S. government without going through CRA vetting and that nearly 470,000 records were transferred in its first two years.99 Canadian privacy advocates are concerned about whether the data can be transferred safely. Others would like the CRA to inform people whose bank information is being transferred.100 A related issue concerns what is commonly known as the 2017 U.S. Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (P.L. 115-97). Section 965 requires that untaxed foreign earnings and profits from foreign subsidiaries of U.S. shareholders (controlled foreign corporations) be subject to a one-time 8% transition tax on earnings reinvested in illiquid assets (such as plants and equipment) and a 15.5% transition tax on cash and cash equivalents as if those earnings and profits had been repatriated to the United States on a retroactive basis back to 1986.101 The tax consequences of this can be severe for U.S. or dual-citizenship residents who own Canadian corporations or have incorporated themselves, yet for the purposes of the act are treated the same as a large corporation keeping assets in offshore subsidiaries. According to some reports, the cumulative effect of these measures resulting from citizenship-based taxation is that many dual-citizens or "accidental Americans" are seeking to revoke their U.S. citizenship.102 |

Wine Exports

On May 25, 2018, the United States requested the establishment of a dispute settlement panel over restrictions on U.S. wine exports, specifically in British Columbia. The province has adopted regulations to restrict grocery store sales to BC wine, and allow imported wine to be sold in grocery stores only in a "store within a store" setting. The United States maintains this is a violation of GATT Article III, which provides for national (nondiscriminatory) treatment of foreign and domestic goods. The United States had previously sought consultations over this regulation in 2016 and 2017, joined by the European Union; the request for a panel is the next step in the WTO dispute settlement process. Canada may reject the first request to establish a panel, but it must accede to the establishment of a panel at the second request, usually at the next monthly meeting of the WTO Dispute Settlement Body. Although the province promulgated the regulations, Canada must defend the province in WTO dispute settlement.103

Energy