Introduction

From the mid-1970s to the mid-1990s, economic and trade relations between the United States and Vietnam remained virtually frozen, in part a legacy of the Vietnam War. On May 2, 1975, after the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (North Vietnam) defeated U.S. ally the Republic of Vietnam (South Vietnam), President Gerald R. Ford extended President Richard M. Nixon's 1964 trade embargo on North Vietnam to cover the reunified nation.1 Under the Ford embargo, bilateral trade (including arms sales) and financial transactions were prohibited.

Economic and trade relations between the two nations began to thaw during the Clinton Administration, building on joint efforts during the Reagan and George H. W. Bush Administrations to resolve a sensitive issue in the United States—recovering the remains of U.S. military personnel declared "missing in action" (MIA) during the Vietnam War.2 The shift in U.S. policy also was spurred by Vietnam's withdrawal from Cambodia.3 President Bill Clinton ordered an end to the U.S. trade embargo on Vietnam on February 3, 1994,4 and on July 11, 1995, the United States and Vietnam restored diplomatic relations.5 Two years later, President Bill Clinton appointed the first U.S. ambassador to Vietnam since the end of the Vietnam War.

Bilateral relations also improved in part due to Vietnam's 1986 decision to shift from a Soviet-style central planned economy to a form of market socialism. The new economic policy, known as doi moi ("change and newness"), ushered in a period of 30 years of rapid growth in Vietnam. Since 2000, Vietnam's real GDP growth has averaged over 6% per year. Much of that growth was generated by foreign investment in Vietnam's manufacturing sector, particularly its clothing industry.

The United States and Vietnam signed a bilateral trade agreement (BTA) on July 13, 2000, which went into force on December 10, 2001.6 As part of the BTA, the United States extended to Vietnam conditional most favored nation (MFN) trade status, now known as normal trade relations (NTR). Economic and trade relations further improved when the United States granted Vietnam permanent normal trade relations (PNTR) status on December 29, 2006, as part of Vietnam's accession to the World Trade Organization (WTO).7 In June 2007, the United States and Vietnam signed a Trade and Investment Framework Agreement (TIFA), and set up a ministerial-level Trade and Investment Council to discuss issues related to the implementation of the TIFA and WTO agreements, as well as trade and investment policies in general.

Since signing the TIFA, Vietnam has indicated a desire to foster closer trade relations. In 2008, Vietnam applied for acceptance into the U.S. Generalized System of Preferences (GSP) program and the two nations started negotiations of a bilateral investment treaty (BIT). Both those initiatives, however, receded in importance once Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) negotiations got underway in 2008.8 The United States also has expressed an interest in closer economic relations, but has told the Vietnamese government that it needs to make certain changes in the legal, regulatory, and operating environment of its economy to conclude the BIT agreement or to qualify for the GSP program.

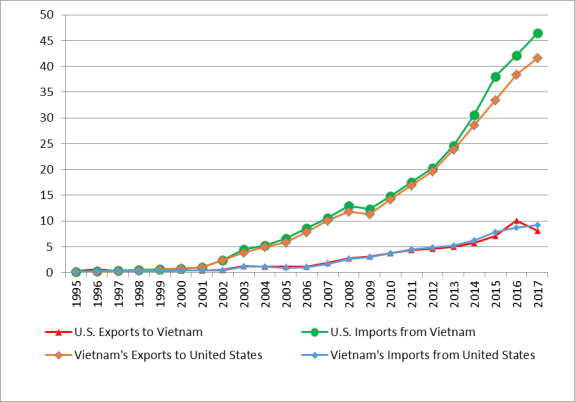

For the first few years following the end of the U.S. embargo in 1994, trade between the two nations grew slowly, principally because of Vietnam's lack of NTR (see Figure 1). However, following the granting of conditional NTR in December 2001, trade flows between the United States and Vietnam grew quickly. According to both nations' official trade statistics, merchandise trade nearly doubled between 2001 and 2002. Bilateral trade continued to climb after the United States granted PNTR status to Vietnam in 2006. U.S. imports from Vietnam slid 4.7% in 2009 because of the U.S. economic recession, but have rebounded sharply since 2010. According to U.S. trade statistics, U.S. exports to Vietnam declined by nearly $2 billion in 2017, but Vietnamese trade statistics show an increase in imports from the United States of almost $500 million.9

The growth in bilateral trade also has created sources of friction over specific goods. A rapid increase in Vietnam's clothing exports to the United States led to the implementation of a controversial monitoring program from 2007 to 2009.10 The growth in Vietnam's catfish exports (also known as basa, swai, and tra) has also generated tensions between the two nations (see "Catfish" section below). The recent growth of new merchandise exports from Vietnam, such as electrical machinery, may become subject to future bilateral trade friction.

|

Figure 1. U.S.- Vietnam Bilateral Merchandise Trade Official trade figures in billions of U.S. dollars |

|

|

Source: U.S. International Trade Commission; General Statistics Office (GSO) of Vietnam and Vietnam Customs. See Appendix for details. |

A possible area for growth in U.S. exports to Vietnam is arms sales (see "Arms Sales" section below). In May 2016, President Obama announced that he would lift the remaining restrictions on arms sales to Vietnam.11 The Trump Administration has repeatedly signaled its interest in increasing arms sales to Vietnam, and has reportedly made such sales a priority for the Defense Department, the State Department, and the U.S. embassy in Hanoi.12 So far, such arms sales have been limited, despite the expressed interest displayed by both governments.

Bilateral Trade Balance

The Trump Administration has indicated that reducing U.S. bilateral trade deficits will be a priority in its trade policy. During a June 2017 meeting with South Korea's President Moon Jae-in, President Trump reportedly said, "The United States has trade deficits with many, many countries, and we cannot allow that to continue."13 The $32 billion bilateral merchandise trade deficit with Vietnam in 2016 was reportedly a major issue during President Trump's May 2017 meeting at the White House with Vietnam's Prime Minister Nguyen Xuan Phuc.14 The bilateral trade deficit also was discussed during President Trump's meeting with Vietnam's President Tran Dai Quang in Hanoi in November 2017.15

Since 2001, the U.S. merchandise trade deficit with Vietnam has risen significantly, resulting in its rise from 45th largest in 2001 to the 5th largest bilateral deficit in 2017 (see Table 1).16 The increase in the U.S. trade deficit with Vietnam has been largely driven by substantial and successive increases in the import of new types of goods from Vietnam, starting in the early 2000s with clothing, apparel and footwear, and then from 2012 to 2017 expanding into electronics and machinery. This growth largely reflects changes in Asia's regional supply chains, in which major manufacturers from China, Japan, South Korea, the United States, and other nations have relocated some of their production facilities to Vietnam, resulting in an increase in Vietnamese exports.17

Table 1. Rise in U.S. Bilateral Merchandise Trade Deficit with Vietnam

Value (in US$ millions) and Ranking

|

Year |

Value |

Ranking |

|

|

2001 |

|

45th |

|

|

2006 |

|

25th |

|

|

2011 |

|

17th |

|

|

2017 |

|

5th |

Source: U.S. International Trade Commission

The joint statement issued following Prime Minister Phuc's May 2017 meeting with President Trump identified a number of measures to be taken to "actively promote mutually beneficial and ever-growing economic ties to bring greater prosperity to both countries."18 The measures included:

- Both nations "creating favorable conditions for the businesses of both sides, particularly through the effective use of the Trade and Investment Framework Agreement to address issues in United States-Vietnam relations in a constructive manner";

- Vietnam pursuing "a consistent policy of economic reform and international integration, creating favorable conditions for foreign companies, including those of the United States, to do business and invest in Vietnam";

- Vietnam protecting and enforcing intellectual property;

- Vietnam "bringing its labor laws in line with Vietnam's international commitments"; and

- Both nations pledging "to continue to work together constructively to seek resolution of other priority issues of each country, including those related to intellectual property, advertising and financial services, information-security products, white offal, distiller's dried grains, siluriformes, shrimp, mangos, and other issues."19

Following their November 2017 meeting, President Quang and President Trump released a joint statement that stated:

The two leaders pledged to deepen and expand the bilateral trade and investment relationship between the United States and Vietnam through formal mechanisms, including the Trade and Investment Framework Agreement (TIFA). … The leaders committed to seek resolution of remaining agricultural trade issues, including those regarding siluriformes, shrimp, and mangoes, and to promote free and fair trade and investment in priority areas, including electronic payment services, automobiles, and intellectual property rights enforcement.20

In addition, Vietnam's Minister of Trade and Investment Tran Tuan Anh met with U.S. Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer on May 30, 2017, and asked that the United States recognize Vietnam as a market economy, lift the new catfish inspection regulations, and accelerate the licensing of Vietnamese fruit exports to the United States.21

Trade and Investment Framework Agreement (TIFA)

As both joint statements indicate, the United States and Vietnam have agreed to utilize the 2007 bilateral TIFA, and its Trade and Investment Council (the Council), as a major vehicle to discuss trade and investment issues.22 According to Article Two of the TIFA, the Council "shall endeavor to meet no less than once a year."

The two nations held the first Council meeting since 2011on March 27-28, 2017, in Hanoi.23 During the meeting, Assistant U.S. Trade Representative Barbara Weisel urged Vietnam to address certain bilateral trade issues, such as agriculture and food safety, intellectual property, digital trade, financial services, customs, industrial goods, transparency and good governance, and illegal wildlife tracking. During a May 2017 meeting with U.S. Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer, Minister of Industry and Trade Tran Tuan Anh urged the United States to recognize Vietnam as a market economy, repeal the special catfish inspection procedures (see "Catfish" below), and reduce barriers to Vietnamese fruit imports.24

Catfish

Catfish have been a source of trade friction between the United States and Vietnam since 2002. Vietnam is a major exporter of frozen fish fillets using certain varieties of fish—known as basa, swai, and tra in Vietnamese—that are commonly referred to as catfish in the global fish market.25 Since 1999, Vietnamese exports of basa, swai, and tra frozen fish fillets have secured a growing share of the U.S. market, despite the objections of the U.S. catfish industry and the actions of the U.S. government. In 2017, the United States imported almost $345 million in catfish from Vietnam.26

|

Year |

Value of Imports |

||

|

2001 |

|

||

|

2002 |

|

||

|

2003 |

|

||

|

2004 |

|

||

|

2005 |

|

||

|

2006 |

|

||

|

2007 |

|

||

|

2008 |

|

||

|

2009 |

|

||

|

2010 |

|

||

|

2011 |

|

||

|

2012 |

|

||

|

2013 |

|

||

|

2014 |

|

||

|

2015 |

|

||

|

2016 |

|

||

|

2017 |

|

Source: USITC

Notes: Includes HTSUS codes 030272, 030324, 030420, 030429, 030432, 030451, 030462, and 030451.

Over the last 16 years, the United States has taken several actions that have had an impact on the import of Vietnamese catfish (see Table 2). In 2002, Congress passed legislation that prohibited the labeling of basa, swai, and tra as "catfish" in the United States.27 In August 2003, the U.S. government imposed antidumping duties on "certain frozen fish fillets from Vietnam," including basa, swai, and tra.28 In June 2009, the ITC determined to keep the duties in place "for the foreseeable future." According to the Vietnam Association of Seafood Exporters and Producers (VASEP), the number of companies exporting catfish to the United States declined from 30 to 3 following the imposition of antidumping duties.29 Although U.S. imports of Vietnamese catfish declined in 2003 and 2005, possibly as a result of legislation and antidumping duties, after 2005, U.S. imports of basa, swai, and tra from Vietnam continued to rise.

In the 2008 Farm Bill (P.L. 110-246), Congress transferred catfish inspection (including basa, swai, and tra) from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA); Congress confirmed that transfer in the Agriculture Act of 2014 (P.L. 113-79). The Secretary of Agriculture sent draft regulations to the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) in November 2009; the final regulations were published in December 2015. The new regulations took effect on March 1, 2016, but provided a transition period lasting until September 1, 2017, before full implementation would take place.30 The inspection program was implemented as scheduled.

Vietnam's Response

In the eyes of the Vietnamese government, the U.S. response to the growth of Vietnam's basa, swai, and tra exports constitutes a case of trade protectionism designed to shelter U.S. catfish producers from legitimate competition. Following the passage of the 2008 Farm Bill, then-Ambassador to the United States Le Cong Phung sent a letter to nearly 140 Members of Congress, suggesting that a reclassification of basa and tra as catfish would call into question the U.S. commitment to the WTO and endanger the jobs of more than 1 million Vietnamese farmers and workers. In addition, an opinion article in the Wall Street Journal referred to the possible reclassification of basa, swai, and tra as catfish as "protectionism at its worst."31 Vietnam also pointed to U.S. anti-dumping measures on Vietnamese shrimp and plastic bags as an indication of U.S. protectionism.

Starting in 2010, Vietnam's Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development (MOARD) tightened export hygiene standards for basa, swai, and tra, in anticipation of the new U.S. inspection regulations. Effective April 12, 2010, all basa and tra exported from Vietnam needed certificates for hygiene and food safety issued by the National Agro-Forestry-Fisheries Quality Assurance Department.32 In addition, MOARD and the Ministry of Industry and Trade contracted U.S.-based Mazzetta Company to train Vietnamese fish breeders on how to comply with U.S. standards.33 In 2011, then Prime Minister Dung reportedly approved a 10-year, $2 billion "master plan" for the development of Vietnam's fish farming industry that is designed to promote infrastructure and technological development, disease control, and environmental improvement.34

Following the publication of the new U.S. catfish regulations, a spokesperson for Vietnam's Ministry of Foreign Affairs reportedly expressed disappointment, stating the new regulations are unnecessary, could constitute a non-tariff trade barrier, reduce Vietnamese exports, and harm the lives of Vietnamese farmers.35 Vietnamese officials also reportedly indicated that the 18-month transition period to comply with the new U.S. standards was much shorter than the customary five years granted to developing nations, and suggested that the new regulations may violate the WTO sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) Agreement.36

On February 22, 2018, Vietnam filed a WTO complaint that the U.S. inspection program for catfish imports violates the WTO SPS Agreement.37 In its complaint, Vietnam asserted that the United States had no scientific basis for subjecting imported catfish to a special inspection program. Under WTO procedures, Vietnam is requesting consultation with the United States to resolve the dispute. If, after 60 days, the two nations cannot resolve the dispute, Vietnam can request a formal WTO panel to review and adjudicate the complaint.

The Antidumping Sunset Review on Catfish

While the USDA prepared the new catfish regulations, the ITC issued, on June 15, 2009, a final determination in its five-year (sunset) review of the existing antidumping duties on "certain frozen fish fillets from Vietnam."38 In a unanimous decision, the six ITC commissioners voted to continue the antidumping duties "for the foreseeable future." In April 2014, the Department of Commerce lowered the antidumping duties on Vietnam's catfish exports to the United States.39

On January 12, 2018, Vietnam filed a request for consultations with the WTO's Dispute Settlement Body (DSB) regarding the imposition of anti-dumping duties and cash deposit requirements by the U.S. Department of Commerce on "Certain Frozen Fish Fillets" from Vietnam.40 On March 8, China submitted a request to be a party to the consultations, noting, "A substantial portion of China's Pangasius seafood product is exported to the United States' market."41 The United States has 60 days in which to respond to the request and resolve the matter. After 60 days, Vietnam may request adjudication by a WTO dispute panel. As of mid-April, Vietnam has not requested a formal review.

Arms Sales

In 1975, U.S. military sales to Vietnam were banned as part of the larger U.S. ban on bilateral trade.42 In 1984, the U.S. government included Vietnam on the International Traffic in Arms Regulations (ITAR) list of countries that were denied licenses to acquire defense articles and defense services. The ITAR restrictions on arms sales remained in effect after President Clinton lifted the general trade embargo in February 1994. In April 2007, the Department of State amended ITAR to permit "on a case-by-case basis licenses, other approvals, exports or imports of non-lethal defense articles and defense services destined for or originating in Vietnam." To the Vietnamese government, the continuing restrictions on trade in military equipment and arms were a barrier to the normalization of diplomatic relations and constrained closer bilateral ties.

|

Fiscal Year |

2009 |

2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

||||||||||||||||||

|

Amount |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Source: CRS analysis of U.S. budget data.

Vietnam was subsequently permitted to participate in the Foreign Military Financing (FMF) program, administered by the State Department, starting in fiscal year 2009 (see Table 3). Via FMF, Vietnam was able to purchase spare parts for Huey helicopters and M113 Armored Personnel Carriers captured during the Vietnam War. According to the Defense Security Cooperation Agency (DSCA), U.S. military sales agreements with Vietnam rose from $653,000 in fiscal year 2011 to $20 million in fiscal year 2016.43

In October 2014, as relations continued to deepen, the Obama Administration partially relaxed U.S. restrictions on the transfer of lethal weapons and articles to Vietnam to permit "future transfer of maritime security-related" defense articles, again on a case-by-case basis. The Department said that the move would help the United States "integrate Vietnam fully into maritime security initiatives" by helping Vietnam to "improve its maritime domain awareness and maritime security capabilities."44 While in Hanoi in May 2016, President Obama announced the removal of remaining U.S. restrictions on sales of lethal weapons and related services to Vietnam.45 At the time, U.S. officials and some observers argued that such an action would help improve Vietnam's capacity to respond to China in the South China Sea and solidify the growing strategic partnership between the United States and Vietnam. Others, however, called the move premature without improvements in human rights conditions in Vietnam.

The Trump Administration has indicated that it sees increased U.S. arms sales to Vietnam as one means of reducing the bilateral merchandise trade deficit, as well as strengthening the security partnership with Vietnam. The State Department reportedly is encouraging Vietnam to diversify its source of arms away from its "historical suppliers" (such as Russia) and include more U.S. equipment.46 Overseas U.S. weapons sales also are an important part of the Trump Administration's "Buy American" proposal, which reportedly will require the Pentagon and U.S. diplomats to play a more active role in promoting arms trade, as well as possible easing of ITAR restrictions.47

The impact of removing the restrictions on arms sales to Vietnam is unclear. Following the 2014 partial easing of the arms export ban, few lethal defense articles were sold or transferred to Vietnam from the United States. A refurbished Hamilton-class cutter was transferred to Vietnam through the Excess Defense Article (EDA) program on May 25, 2017. Also in May 2017, the first tranche of six Metal-shark patrol boats were delivered, financed via the FMF program.48 The State Department anticipates that Vietnam will use future FMF funding to acquire additional U.S.-origin defense articles. Vietnam reportedly is interested in obtaining F-16 fighter aircraft, P-3C Orion maritime patrol aircraft, and maritime intelligence surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR) equipment.49

The potential sale of arms to Vietnam had been a source of some controversy for Congress. While some Members support the provision of lethal assistance, others object in part because of Vietnam's alleged human rights record. Congress will have oversight of some exports of military items to Vietnam, pursuant to Section 36(b) of the Arms Export Control Act (AECA; P.L. 90-629). That law requires the executive branch to notify the Speaker of the House, the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, and the House Foreign Affairs Committee before the Administration can take the final steps to conclude either a government-to-government or commercially licensed arms sale. For potential sales to Vietnam, the Administration is required to notify the congressional committees and leadership 30 calendar days before concluding sales of major defense equipment, defense articles, defense services, or design and construction services meeting certain value thresholds.

Non-Market Economy Designation

Vietnamese leaders would like the United States to change Vietnam's official designation under U.S. law from "nonmarket economy" to "market economy."50 The United States' designation of Vietnam as a non-market economy, which, according to the Vietnamese government, will expire in 2019 under the terms of its accession to the World Trade Organization (WTO), generally makes it more likely that antidumping and countervailing duty cases would result in the Commerce Department issuing adverse rulings against Vietnamese companies' exports to the United States.

|

Vietnam's Economy at a Glance In 1986, Vietnam started the transformation of its Soviet-style centrally planned economy into a market-oriented economy. Its agricultural sector, which was decollectivized in the 1990s, remains the main source of employment in the country, but provides about 20% of GDP. The industrial sector, which contributes about 40% of GDP, has also undergone a gradual shift from state-owned to privately owned production. Vietnam's industrial output currently is produced by foreign-owned enterprises (about 45% of industrial output), privately owned domestic companies (about 35% of industrial output), and state-owned enterprises (about 20% of industrial output). Vietnam's services sector (about 40% of GDP) has also transitioned from primarily government-run to primarily private providers. Most goods and services are now distributed using market mechanisms, but there remains significant government intervention via subsidies for key industries and selected consumer goods. Vietnam's financial system is still dominated by state-owned banks, but some private banks have emerged. Vietnam's GDP grew by 6.8% in 2017, fueled by construction and industrial sector growth. Inflation in Vietnam in 2017 was 3.5%. The unemployment rate remained low, but Vietnam continues to have significant underemployment. Vietnam's total exports were $214 billion; imports were $211 billion. Although the shift in economic policy has led to strong growth, it has also brought many of the traditional problems of market-oriented economies. Vietnam has periodically struggled with inflation, fiscal deficits, trade imbalances, and other cyclical economic phenomena common to market economies. Vietnam has also seen a rising income and wealth disparity, which at times has fueled discontent among Vietnam's poor and lower-income population. Vietnam's economic priorities for 2018 are reforming its state-owned enterprises and maintaining macroeconomic stability. Source: General Statistics Office of Vietnam. |

Under U.S. trade law (19 U.S.C. 1677), the term "nonmarket economy country" means "any foreign country that the administering authority determines does not operate on market principles of cost or pricing structures, so that sales of merchandise in such country do not reflect the fair value of the merchandise." "Nonmarket economy" status is particularly significant for antidumping (AD) and countervailing duty (CVD) cases heard by the U.S. International Trade Administration (ITA) and ITC. In making such a determination, the administrating authority of the executive branch (the Department of Commerce) is to consider such criteria as the extent of state ownership of the means of production, and government control of prices and wages. However, the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), the forerunner of the World Trade Organization (WTO), implicitly defines a "non-market economy" for purposes of trade as "a country which has a complete or substantially complete monopoly of its trade and where all domestic prices are fixed by the State."51

For over 20 years, Vietnam has been transitioning from a centrally planned economy to a market economy. Under its doi moi policy, Vietnam has allowed the development and growth of private enterprise and competitive market allocation of most goods and services. Although most prices have been deregulated, the Vietnamese government still retains some formal and informal mechanisms to direct or manage the economy.

State-Owned Enterprises

For the United States, one of the main concerns about Vietnam's economy is the continued importance of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) in the nation's industrial sector. In the early 1990s, the number of SOEs in Vietnam declined from more than 12,000 to fewer than 7,000. By 2001, the number of SOEs had reduced to fewer than 5,400, and between 2001 and 2005, more than 40% of the SOEs had been partially privatized. Between 2005 and 2013, the portion of Vietnam's GDP produced by SOEs declined from 37.6% to 28.7%.52 However, SOEs continue to dominate key sectors of Vietnam's economy, such as mining and energy.

Many of Vietnam's SOEs have been converted into quasi-private corporations through a process known as "equitization," in which some shares are sold to the public on Vietnam's stock exchange, but most of the shares remain owned by the Vietnamese government. According to the Vietnam Economic Institute, 530 SOEs have been equitized over the last five years.53

Following the 12th National Congress of the Communist Party of Vietnam (CPV) in January 2016 and the introduction of a new government led by Prime Minister Nguyen Xuan Phuc, Vietnam seemingly made plans for the equitization of more SOEs. In February 2017, the government promulgated a directive requesting the Ministry of Finance to enact regulations and procedures to facilitate equitization of SOEs. In May 2017, the government approved a blueprint for SOE restructuring in the 2016-2020 period, under which the government aims to equitize 137 more SOEs by 2020, including many of the larger SOEs. These include Agribank, Mobifone, PV Power, PV Oil, Saigon Jewelry Company (SJC), Saigon Trading Group (Satra), Saigon Tourist Vietnam Multimedia Corporation (VTC), Vietnam Posts and Telecommunications Group (VNPT), Vietnam Rubber Group (VRG), Vinacafe, Vinachem, Vinacomin, Vinafood 2, and Vinataba. The pace of equitization for the first half of 2017, however, was relatively slow, with 19 SOE equitization plans approved.54

To some analysts, however, the retention of a controlling interest in the shares of the companies provides the Vietnamese government with the means to continue to manage the operations of the equitized SOEs. According to one Vietnamese economist, although 96% of the remaining SOEs have been equitized, only 8% of the capital has been transferred to private investors, as the share of equity sold has been kept low.55

Price and Wage Controls

The doi moi process has led to the gradual deregulation of most prices and wages in Vietnam. However, the Vietnamese government maintains controls over key prices, including certain major industrial products (such as cement, coal, electricity, oil, and steel) and basic consumer products (such as meat, rice, and vegetables). On wage control, Vietnamese government workers are paid according to a fixed pay scale, and all workers are subject to a national minimum wage law. Workers for private enterprises, foreign-owned ventures, and SOEs receive wages based largely on market conditions. The Vietnamese government asserts that most of the prices and wages in Vietnam are market-determined, especially the prices of goods exported to the United States.

Vietnam's View

The Vietnamese government maintains that its economy is as much a market economy as many other nations around the world, and actively has sought formal recognition as a market economy from its major trading partners. A number of trading partners—including the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), Australia, India, Japan, and New Zealand—have designated Vietnam a market economy for purposes of international trade. Under the terms of its WTO accession agreement with the United States, Vietnam is to remain a non-market economy for up to 12 years after its accession (i.e., 2019) or until it meets U.S. criteria for a "market economy" designation.56

Designation as a market economy has both symbolic and practical value for Vietnam. The Vietnamese government views market economy designation as part of the normalization of trade relations with the United States. In addition, Vietnam's designation as a nonmarket economy generally makes it more likely that AD and CVD cases will result in adverse rulings and higher imposed duties against Vietnamese companies.57 The 115th Congress could consider legislation weighing in on the designation of Vietnam as a market or nonmarket economy by amending or superseding existing U.S. law.

IPR Protection

The U.S. government remains critical of Vietnam's record on intellectual property rights (IPR) protection. Vietnam was included in the "Watch List" in the U.S. Trade Representative's 2017 Special 301 Report, an annual review of the global state of IPR protection and enforcement.58 Vietnam remained on the Watch List because of its continuing issues with online piracy and the sales of counterfeit goods. The report states:

Enforcement continues to be a challenge for Vietnam. Piracy and sales of counterfeit goods online remain common. Unless Vietnam takes stronger enforcement action, online piracy and sales of counterfeit goods are likely to worsen as more Vietnamese people obtain broadband Internet access and smartphones. Counterfeit goods, including counterfeits of high-quality, remain widely available in physical markets, and, while still limited, domestic manufacturing of counterfeit goods is emerging as a concern.

Bilateral Investment Treaty (BIT) Negotiations

During their June 2008 meeting, President Bush and Prime Minister Dung announced the launch of talks to establish a bilateral investment treaty (BIT). BITs are designed to improve the climate for foreign investors by establishing dispute settlement procedures and protecting foreign investors from performance requirements, restrictions on transferring funds, and arbitrary expropriation. The United States currently is a party to 40 BITs; Vietnam has signed over 50.

The first round of BIT negotiations was held in Washington, DC, on December 15-18, 2008. Since then, two more rounds of talks have been held—one on June 1-2, 2009, in Hanoi, and another on November 17-19, 2009, in Washington, DC. A proposed fourth round of talks that was to be held in early 2010 did not happen. According to the State Department, no BIT talks were held after the two nations joined the TPP negotiations, presumably because the TPP agreement would have encompassed those issues that would be addressed in the BIT.

The existing 2001 Bilateral Trade Agreement (BTA) between the United States and Vietnam included provisions in Chapter 4 governing investment and the future negotiation of a BIT.59 Specifically, Article 2 commits both nations to providing national and MFN (NTR) treatment to investments. Article 4 provides for a dispute settlement system for bilateral investments. Article 5 requires both nations to ensure that the laws, regulations, and administrative procedures governing investments are promptly published and publicly available. Article 11 pertains to compliance with the provisions of the WTO Agreement on Trade-Related Investment Measures (TRIMs). Article 13 states that both nations "will endeavor to negotiate a bilateral investment treaty in good faith within a reasonable period of time."

If the United States and Vietnam successfully complete the negotiations of a BIT during the 115th Congress, the treaty would be subject to Senate ratification. As of mid-April 2018, BIT negotiations had not resumed. Action on the part of Congress as a whole may be required if the terms of the BIT require changes in U.S. law.

Possible Regional Trade Agreements

Although the United States has withdrawn from the TPP, the remaining 11 nations, including Vietnam, signed a proposed regional trade agreement, the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), on March 8, 2018.60 In addition, Vietnam is among 16 nations negotiating another proposed RTA, the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP).61

If either agreement is implemented, projections of the trade effects of both RTAs show a slight increase in Vietnamese exports to the United States, and a small decrease in U.S. exports to Vietnam, leading to an overall increase in the bilateral trade deficit. According to Vietnam's projections, the CPTTP will increase Vietnam's GDP by 1.32%, its exports by 4.0% and its imports by 3.8%.62

Key Trends in Bilateral Trade

The preceding sections of the report have focused on current and past issues in U.S.-Vietnam trade relations. The final section of the report attempts to identify potential sources of future trade friction by examining trends in bilateral trade and investment statistics. The focus is on three aspects of recent trade relations—merchandise trade, trade in services, and foreign direct investment (FDI).

Merchandise Trade

Over two decades have passed since the opening of trade relations between the United States and Vietnam. As previously mentioned, the rapid growth in Vietnam's export of two types of products—clothing and catfish—quickly made them sources of trade tension between the two nations. However, other commodities that contribute more to U.S.-Vietnam trade flows could also become touch points for challenges in bilateral trade relations.

Table 4. Top 5 U.S. Exports to Vietnam and Imports from Vietnam

(According to U.S. trade statistics for 2017; U.S. $ millions)

|

Top 5 U.S. Exports to Vietnam |

Top 5 U.S. Imports from Vietnam |

||||

|

Product |

Value |

Product |

Value |

||

|

Electrical machinery and equipment and parts thereof; sound recorders and reproducers, television image and sound recorders and reproducers, and parts and accessories of such articles (HTS85) |

|

Electrical machinery and equipment and parts thereof; sound recorders and reproducers, television image and sound recorders and reproducers, and parts and accessories of such articles (HTS85) |

|

||

|

Cotton, including yarns and woven fabrics thereof (HTS52) |

|

Articles of apparel and clothing accessories, knitted or crocheted (HTS61) |

|

||

|

Nuclear reactors, boilers, machinery and mechanical appliances; parts thereofa (HTS84) |

|

Footwear, gaiters and the like; parts of such articles (HTS64) |

|

||

|

Edible fruits and nuts; peel of citrus fruit or melons (HTS8) |

|

Articles of apparel and clothing accessories, not knitted or crocheted (HTS62) |

|

||

|

Oil seeds and oleaginous fruits; miscellaneous grains, seeds and fruits; industrial or medicinal plants; straw and fodder (HTS12) |

|

Furniture; bedding, mattresses, mattress supports, cushions and similar stuffed furnishings; lamps and lighting fittings, not elsewhere specified or included; illuminated signs, illuminated nameplates, and the like; prefabricated buildings (HTS94) |

|

||

|

Total trade |

|

|

|||

According to U.S. trade statistics, the top U.S. imports from Vietnam in 2017, besides clothing, were: electrical machinery; footwear; and furniture and bedding (see Table 4). The top U.S. exports to Vietnam included aircraft; electrical machinery; cotton; machinery and mechanical appliances; edible fruit and nuts; and oil seeds. The juxtaposition of these two lists reveals product categories that may warrant watching for their emerging importance in bilateral trade, as well as a connection between some of the top trade commodities. Particularly noticeable in 2017 was the rise of electrical machinery as the leading import from Vietnam; in 2014, it was the third largest import after the two apparel categories. Similarly, footwear rose from being the fourth largest import in 2014 to the third largest import in 2017.

Product Interplay

There is also a discernable interplay between Vietnam's top exports to the United States and the top U.S. exports to Vietnam. Vietnam imports substantial amounts of cotton from the United States, which is then used to manufacture clothing to be exported to the United States. Similarly, Vietnam imports wood from the United States that may end up in the furniture that is imported by the United States from Vietnam. There is also a significant amount of cross-trade in electrical machinery as parts and components are shipped back and forth across the Pacific Ocean. The implication is that potential efforts to curtail the growth of certain top exports of Vietnam to the United States could result in a decline in U.S. exports to Vietnam.

Electrical Machinery

According to USITC, Vietnam's electrical machinery exports to the United States have grown significantly since 2001, from less than $1 million to just under $1 billion in 2011 and then increasing to more than $8.3 billion in 2015 and $11.0 billion in 2017. Electrical machinery constituted more than 23% of total U.S. imports from Vietnam in 2017. According to interviews with foreign investors in Vietnam, there is great potential for growth in this sector because of Vietnam's relatively inexpensive, skilled workers. Vietnamese economic officials have indicated that expanding the production of higher-valued consumer electronics and other electrical devices is a priority for the nation's transition to a middle-income economy.

Footwear

While most of the focus of bilateral trade discussions has been on the sizeable clothing imports from Vietnam, footwear constituted nearly 12% of total U.S. imports from Vietnam in 2017. Vietnam was the second-largest source of footwear imports for the United States in 2017 (after China), more than three times the size of imports from Indonesia (the next largest source).

Furniture and Bedding

Since 2004, Vietnam has risen from being the 62nd-largest source for furniture and bedding imports for the United States to being the 4th-largest source—surpassing past leaders such as Italy, Malaysia, and Taiwan. Furniture and bedding accounted for 10% of total U.S. imports from Vietnam in 2017.

Trade in Services

The United States has generally run a bilateral trade surplus in services with Vietnam, and perceives a trade advantage in several of the services sectors, especially financial services. According to the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, the United States exported $2.2 billion in services to Vietnam in 2016, and imported $1.2 billion in services.63 In the U.S. National Trade Estimate (NTE), the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative indicated that as part of the implementation of the 2001 BTA, Vietnam has committed to greater liberalization of a broad array of its services sectors, including financial services, telecommunications, express delivery, distribution services, and certain professions. It is likely that the United States will press Vietnam for more access during any BIT negotiations.

Foreign Direct Investment

In 2016, Vietnam licensed 2,613 foreign direct investment (FDI) projects worth $26.9 billion.64 The leading source of FDI in 2016 was South Korea, with 849 projects worth $8.0 billion. The United States was the 13th-largest source of FDI in 2016 with 65 projects worth $430 million. The accumulated value of FDI in Vietnam for the period 1989-2016 is $293.7 billion. South Korea was the leading investor during this period, followed by Japan and Singapore. The United States was the 9th-largest investor, with 817 projects worth $10.1 billion.

U.S. interest in investment opportunities in Vietnam could have an impact on possible BIT negotiations. In addition, as more U.S. companies invest in Vietnam, there is the possibility of more business-to-business disagreements between U.S. and Vietnamese companies, and more constituent pressure on Congress to address perceived shortcomings in Vietnam's treatment of foreign-owned enterprises.

Looking Ahead

Prospects for U.S-Vietnam trade relations for 2018 and beyond will depend on various factors, including the growth in bilateral merchandise trade and the potential resolution of Vietnam's challenge of U.S. catfish regulations. According to the USITC, U.S. imports from Vietnam were up 5.2% year-on-year for the first two months of 2018, while U.S. exports to Vietnam were down 2.4%, possibly indicating that the U.S. bilateral merchandise trade deficit with Vietnam will continue to grow.

On April 29, 2017, President Trump issued Executive Order 13796, "Addressing Trade Agreement Violations and Abuses," which, among other things, requires the Secretary of Commerce, and the U.S. Trade Representative to "conduct comprehensive performance reviews" of "all trade relations with countries governed by the rules of the World Trade Organization with which the United States does not have free trade agreements but with which the United States runs significant trade deficits in goods." Vietnam is one such country.

The Agriculture and Nutrition Act of 2018 (H.R. 2, so called "2018 Farm Bill") was introduced in the House on April 12, 2018, and includes no provisions with regards to the catfish inspection program. On March 19, 2018, Senator John McCain and Senator Jeanne Shaheen, in a letter to U.S. Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer, asked the Trump Administration to terminate the catfish inspection program before the WTO consultation ended.65 In the letter, the two Senators assert, "Since its implementation, the USDA Catfish Inspection Program has done nothing more than erect a damaging trade barrier against Asian catfish imports to protect a handful of domestic catfish farmers in Southern states."66 It remains uncertain if a Senate version of the 2018 Farm Bill will address this issue.

Appendix. Bilateral Merchandise Trade Data

The table below provides the official merchandise trade data for the United States and Vietnam.

Table A-1.Growth in Bilateral Merchandise Trade Between United States and Vietnam

(in millions of U.S. dollars)

|

Year |

U.S. Data |

Vietnamese Data |

||||

|

Exports to Vietnam |

Imports from Vietnam |

Trade Balance |

Exports to United States |

Imports from United States |

Trade Balance |

|

|

1995 |

253 |

199 |

54 |

170 |

130 |

40 |

|

1996 |

616 |

319 |

297 |

204 |

246 |

-42 |

|

1997 |

278 |

388 |

110 |

287 |

252 |

35 |

|

1998 |

274 |

553 |

-279 |

469 |

325 |

144 |

|

1999 |

291 |

609 |

-318 |

504 |

323 |

181 |

|

2000 |

368 |

822 |

-454 |

733 |

363 |

370 |

|

2001 |

461 |

1,053 |

-592 |

1,065 |

411 |

654 |

|

2002 |

580 |

2,395 |

-1,815 |

2,453 |

458 |

1,995 |

|

2003 |

1,324 |

4,555 |

-3,231 |

3,939 |

1,143 |

2,796 |

|

2004 |

1,163 |

5,276 |

-4,113 |

5,025 |

1,134 |

3,891 |

|

2005 |

1,192 |

6,630 |

-5,438 |

5,924 |

863 |

5,061 |

|

2006 |

1,100 |

8,566 |

-7,466 |

7,845 |

987 |

6,858 |

|

2007 |

1,903 |

10,633 |

-8,730 |

10,105 |

1,701 |

8,404 |

|

2008 |

2,790 |

12,901 |

-10,111 |

11,869 |

2,635 |

9,234 |

|

2009 |

3,108 |

12,290 |

-9,182 |

11,356 |

3,009 |

8,347 |

|

2010 |

3,710 |

14,868 |

-11,162 |

14,238 |

3,767 |

10,471 |

|

2011 |

4,341 |

17,485 |

-13,173 |

16,928 |

4,529 |

12,399 |

|

2012 |

4,623 |

20,266 |

-15,645 |

19,668 |

4,827 |

14,841 |

|

2013 |

5,013 |

24,649 |

-19,614 |

23,869 |

5,232 |

18,637 |

|

2014 |

5,725 |

30,584 |

-24,883 |

28,656 |

6,284 |

22,372 |

|

2015 |

7,072 |

37,993 |

-30,932 |

33,480 |

7,800 |

25,680 |

|

2016 |

10,151 |

42,109 |

-31,958 |

38,464 |

8,708 |

29,756 |

|

2017 |

8,164 |

46,483 |

-38,319 |

41,610 |

9,200 |

32,410 |

Source: U.S. data from International Trade Commission (ITC); Vietnamese data from General Statistics Office (GSO) of Vietnam and Vietnam Customs.

Notes: U.S. data valued at F.A.S. and customs value; Vietnam data valued at F.O.B. and C.I.F.