Introduction

In General

The F-35 Joint Strike Fighter (JSF), also called the Lightning II, is a strike fighter airplane being procured in different versions for the Air Force, Marine Corps, and Navy. The F-35 program is DOD's largest weapon procurement program in terms of total estimated acquisition cost. Current Department of Defense (DOD) plans call for acquiring a total of 2,456 F-35s1 for the Air Force, Marine Corps, and Navy at an estimated total acquisition cost, as of December, 2017, of about $325.1 billion in constant (i.e., inflation-adjusted) FY2012 dollars.2 U.S. allies are expected to purchase hundreds of additional F-35s, and eight foreign nations are cost-sharing partners in the program.

The Administration's proposed FY2019 defense budget requested about $10.7 billion in procurement funding for the F-35. This would fund the procurement of 48 F-35As for the Air Force, 20 F-35Bs for the Marine Corps, 9 F-35Cs for the Navy, and continuing development.

The proposed budget also requested about $1.3 billion for F-35 research and development.

Background

The F-35 in Brief

In General

The Joint Strike Fighter was conceived as a relatively affordable fifth-generation aircraft3 that could be procured in highly common versions for the Air Force and the Navy. Initially, the Marine Corps was developing its own aircraft to replace the AV-8B Harrier, but in 1994, Congress mandated that the Marine effort be merged with the Air Force/Navy program in order to avoid the higher costs of developing, procuring, and operating and supporting three separate tactical aircraft designs to meet the services' similar, but not identical, operational needs.4 5

All three versions of the F-35 will be single-seat aircraft with the ability to go supersonic for short periods and advanced stealth characteristics. The three versions will vary in their combat ranges and payloads (see the Appendix). All three are to carry their primary weapons internally to maintain a stealthy radar signature. Additional weapons can be carried externally on missions requiring less stealth.

|

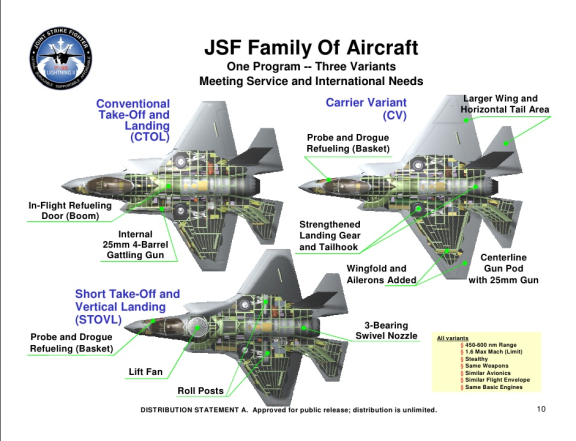

Three Service Versions

From a common airframe and powerplant core, the F-35 is being procured in three distinct versions tailored to the varied needs of the military services. Differences among the aircraft include the manner of takeoff and landing, fuel capacity, and carrier suitability, among others.

Air Force CTOL Version (F-35A)

The Air Force plans to procure 1,763 F-35As, a conventional takeoff and landing (CTOL) version of the aircraft. F-35As are to replace Air Force F-16 fighters and A-10 attack aircraft, and possibly F-15 fighters.6 The F-35A is intended to be a more affordable complement to the Air Force's F-22 Raptor air superiority fighter.7 The F-35A is not as stealthy8 nor as capable in air-to-air combat as the F-22, but it is designed to be more capable in air-to-ground combat than the F-22, and stealthier than the F-16.

|

What Is Stealth? "Stealthy" or "low-observable" aircraft are those designed to be difficult for an enemy to detect. This characteristic most often takes the form of reducing an aircraft's radar signature through careful shaping of the airframe, special coatings, gap sealing, and other measures. Stealth also includes reducing the aircraft's signature in other ways, as adversaries could try to detect engine heat, electromagnetic emissions from the aircraft's radars or communications gear, and other signatures. Minimizing these signatures is not without penalty. Shaping an aircraft for stealth leads in a different direction from shaping for speed. Shrouding engines and/or using smaller powerplants reduces performance; reducing electromagnetic signatures may introduce compromises in design and tactics. Stealthy coatings, access port designs, and seals may require higher maintenance time and cost than more conventional aircraft. |

If the F-15/F-16 combination represented the Air Force's earlier-generation "high-low" mix of air superiority fighters and more-affordable dual-role aircraft, the F-22/F-35A combination might be viewed as the Air Force's intended future high-low mix.9 The Air Force states that "The F-22A and F-35 each possess unique, complementary, and essential capabilities that together provide the synergistic effects required to maintain that margin of superiority across the spectrum of conflict…. Legacy 4th generation aircraft simply cannot survive to operate and achieve the effects necessary to win in an integrated, anti-access environment."10

Marine Corps STOVL Version (F-35B)

The Marine Corps plans to procure 353 F-35Bs, a short takeoff and vertical landing (STOVL) version of the aircraft.11 F-35Bs are to replace Marine Corps AV-8B Harrier vertical/short takeoff and landing attack aircraft and Marine Corps F/A-18A/B/C/D strike fighters, which are CTOL aircraft. The Marine Corps decided to not procure the newer F/A-18E/F strike fighter12 and instead wait for the F-35B in part because the F/A-18E/F is a CTOL aircraft, and the Marine Corps prefers aircraft capable of vertical operations. The Department of the Navy states that "The Marine Corps intends to leverage the F-35B's sophisticated sensor suite and very low observable, fifth generation strike fighter capabilities, particularly in the area of data collection, to support the Marine Air Ground Task Force well beyond the abilities of today's strike and EW [electronic warfare] assets."13

Navy Carrier-Suitable Version (F-35C)

The Navy plans to procure 273 F-35Cs, a carrier-suitable CTOL version of the aircraft, and the Marines will also procure 67 F-35Cs.14 The F-35C is also known as the "CV" version of the F-35; CV is the naval designation for aircraft carrier. The Navy plans in the future to operate carrier air wings featuring a combination of F/A-18E/Fs (which the Navy has been procuring since FY1997) and F-35Cs. The F/A-18E/F is generally considered a fourth-generation strike fighter.15 The F-35C is to be the Navy's first aircraft designed for stealth, a contrast with the Air Force, which has operated stealthy bombers and fighters for decades. The F/A-18E/F, which is less expensive to procure than the F-35C, incorporates a few stealth features, but the F-35C is stealthier. The Department of the Navy states that "the commonality designed into the joint F-35 program will minimize acquisition and operating costs of Navy and Marine Corps tactical aircraft, and allow enhanced interoperability with our sister Service, the United States Air Force, and the eight partner nations participating in the development of this aircraft."16

Engine

The F-35 is powered by the Pratt & Whitney F135 engine, which was derived from the F-22's F119 engine. The F135 is produced in Pratt & Whitney's facilities in East Hartford and Middletown, CT.17 Rolls-Royce builds the vertical lift system for the F-35B as a subcontractor to Pratt & Whitney.

Consistent with congressional direction for the FY1996 defense budget, DOD established a program to develop an alternate engine for the F-35. The alternate engine, the F136, was developed by a team consisting of GE Transportation—Aircraft Engines of Cincinnati, OH, and Rolls-Royce PLC of Bristol, England, and Indianapolis, IN. The F136 was a derivative of the F120 engine originally developed to compete with the F119 engine for the F-22 program.

DOD included the F-35 alternate engine program in its proposed budgets through FY2006, although Congress in certain years increased funding for the program above the requested amount and/or included bill and report language supporting the program.

The George W. Bush Administration proposed terminating the alternate engine program in FY2007, FY2008, and FY2009. The Obama Administration did likewise in FY2010. Congress rejected these proposals and provided funding, bill language, and report language to continue the program.

The General Electric/Rolls Royce Fighter Engine Team ended their effort to provide an alternate engine on December 2, 2011.

Fuller details of the alternate engine program and issues for Congress arising from it are detailed in CRS Report R41131, F-35 Alternate Engine Program: Background and Issues for Congress.

Current Program Status

The F-35 is currently in low-rate initial production, with 280 aircraft delivered as of April 2018. At least 250 of those were in U.S. service.18 Four to five aircraft are currently delivered each month, with the production rate scheduled to increase to 120 per year by 2019.19 In keeping with the acquisition plan that overlapped development and production (known as "concurrency"), the F-35 was also in system development and demonstration (SDD), with testing and software development ongoing, from October 2001 until April 11, 2018. The SDD phase will formally continue until the end of Initial Operational Test and Evaluation, when a "Milestone C" full-rate production decision will be made.20

Recent Developments

Significant developments since the previous major edition of this report (July 18, 2016) include the following, many of which are discussed in greater detail later in the report:

Proposed Multi-Year Procurement

In the latest Selected Acquisition Report, DOD disclosed an intention to acquire F-35s through multiyear contracting.

From FY 2021 to the end of the program, the USAF production profile assumes one 3-year multi-year procurement (FY 2021-FY 2023) followed by successive 5-year multi-year procurements beginning in FY2024, with the required EOQ investments and associated savings. The Department of Navy (DoN) did not include EOQ funding in the PB 2019 submission for a multiyear in FY 2021-2023 for either the F-35B or F-35C. The DoN plans to reassess that decision in the coming FY 2020 budget cycle. Therefore, the DoN PB 2019 production profile assumes annual procurements from FY 2021-2023, followed by successive 5-year multi-year procurements from FY 2024 to the end of the program with necessary EOQ investments and associated savings. 21

End of System Development and Demonstration

The F-35 Joint Program Office declared the 17-year System Development and Demonstration (SDD) effort complete on April 11, 2018. "(T)he developmental flight team has conducted more than 9,200 sorties, accumulated 17,000 flight hours and executed more than 65,000 test points."22 The end of the flight test effort does not mark the actual end of SDD, though; that will occur at Milestone C, following the completion of initial operational test and evaluation (IOT&E).

"Preparations for IOT&E are progressing, although the program will not meet several of the readiness criteria until late CY18; as a result, formal entry into IOT&E will not occur before then." 23 The Navy expects IOT&E entry in September 2018. 24 The Director of Operational Test and Evaluation notes that "IOT&E, which provides the most credible means to predict combat performance, likely will not be completed until the end of 2019, at which point over 600 aircraft will already have been built." 25

Changes in International Orders

As noted, the F-35 is an international program, with commitments from program partners and other countries to share in the development costs and acquire aircraft. The other nations' plans have varied over time. Most recently:

- Australia took delivery of two F-35As in 2014 and 2015, and has announced a new order for 58 follow-on aircraft, with the next deliveries in 2018.26 27 However, Australia decided not to acquire F-35Bs.28

- Belgium received U.S. State Department approval for 34 F-35s, although the Belgian government has yet to decide on the winner of its current fighter competition.29

- Following the election of a new government, Canada canceled its decision to acquire 65 F-35s. Canada has remained a formal partner in the program,30 and the Trudeau government has included the F-35 as a candidate for its follow-on fighter requirement.31 According to the F-35 program manager, a Canadian exit could increase the price of an F-35A to the U.S. by "about .7 to 1 percent," or about $1 million.32

- Denmark has confirmed an order for 27 F-35As, possibly going to 30; it had initially been expected to order 48, although the government also reportedly considered withdrawing from the program altogether. 33 The initial contract is expected to be signed in 2018.34

- Japan's buy, initially reported as 42, may be 68 F-35s. 35, 36

- Norway has taken delivery of the first ten of the 52 jets it plans to buy, with three based in country and seven in the US for training.37

- The Netherlands received two of its planned 37 aircraft.38

- Singapore "is still to confirm an order, or even to announce its preferred F-35 variant,"39 but is still "seriously considering" the jet.40

- South Korea is looking at ordering 20 more F-35As and six F-35Bs in addition to the 40 already on order.41, 42

Devolution of Joint Program Office

Section 146 of the FY2017 National Defense Authorization Act (P.L. 114-328) required DOD to examine alternative management structures for the F-35 program. Proponents argued that the overhead structure of a joint office, even if needed for development of a joint aircraft, is not needed once production has been established, and further that the F-35 is functionally three separate aircraft, with much less commonality than earlier envisioned. "[E]ven the Program Executive Officer of the F-35 Joint Program Office, General Christopher Bogdan, recently admitted the variants are only 20–25 percent common."43 Supporters cited the requirement by the United States to support international customers and to oversee further software and other upgrades as reasons to keep the office in place. The Joint Program Office employs 2,590 people, and the annual cost to operate it is on the order of about $70 million a year.44

In a letter to Congress accompanying that report, Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment Ellen Lord declared an intention to

begin a deliberate, conditions-based, and risk-informed transition...from the existing F-35 management structure to an eventual management structure with separate Service-run F-35A and F-35B/C program offices that are integrated with and report through the individual Military Departments.45

Specific timing of the transition, and the responsibilities to be transferred to the services, have not been announced.46

F-35 Preferred Bases Announced

On December 21, 2017, the Air Force announced Naval Air Station Joint Reserve Base Fort Worth, TX, as the preferred alternative for the first F-35A reserve component base. Davis-Monthan Air Force Base, AZ; Homestead Air Reserve Base, FL; and Whiteman AFB, MO, were also candidate bases.

At the same time, Truax Field, WI, and Dannelly Field, AL, were announced as the next Air National Guard F-35A bases, with aircraft slated to arrive in 2023. Gowen Field ANGB, ID; Selfridge ANGB, MI; and Jacksonville Air Guard Station, FL, were also considered. Burlington Air National Guard Base, VT, had previously been selected. 47

Active component F-35As had already been announced as going to Hill AFB, UT, and RAF Lakenheath, England. Eielson AFB, AK, had earlier been announced as the preferred base for the first overseas F-35 squadron.48

Government Suspends Accepting F-35s

In March 2018, DOD stopped accepting new F-35s pending resolution of a dispute with Lockheed Martin over who should pay to repair identified issues with corrosion on F-35s. As of April 12, 2018, five aircraft had been deferred.

This is not the first time acceptances had been stopped. "Last year, the Pentagon stopped accepting F-35s for 30 days after discovering corrosion where panels were fastened to the airframe, an issue that affected more than 200 of the stealthy jets. Once a fix had been devised, the deliveries resumed, and Lockheed hit its target aircraft delivery numbers for 2017."49

At the heart of the dispute is the government's inspection of the planes during Lockheed's production, which failed to discover problems with the fastenings, the sources said. Because neither party caught the issue at the time each is pointing the finger at the other to pay for the fix.50

In testimony before the House Armed Services Committee on April 12, 2018, DOD officials noted that the corrosion issue then in dispute was not the same found in 2016.51

Testing Progress

DOD's annual testing report stated, "As of November 6, 2017, the JPO had collected data and verified performance to close out 252 of 476 (53 percent) contract specification paragraphs; 2,516 of 3,452 (73 percent) success criteria derived from the contract specifications had been completed." 52

However,

"The operational suitability of the F-35 fleet remains at a level below Service expectations and is dependent on work-arounds that would not be acceptable in combat situations. Over the previous year, most suitability metrics have remained nearly the same or moved only within narrow bands, which are insufficient to characterize a trend of performance. Overall fleet-wide monthly availability rates remain around 50 percent, a condition that has existed with no significant improvement since October 2014, despite the increasing number of new aircraft."

Testers found numerous other deficiencies, warning that "The JPO completed two reviews of remaining mission systems testing in CY17 and deleted test points in an attempt to keep developmental flight testing on schedule."53

Software Development Cost Growth

The cost of F-35 Block 4 software, previously estimated at $8 billion, will now require $10.8 billion through FY 2024, according to F-35 program executive officer Vice Admiral Mathias Winter. $3.7 billion of that cost would be borne by international partners, with the U.S. paying $7.1 billion.54

Sustainment Cost Issues

Since 2015, operations and sustainment costs for the F-35 fleet's the lifecycle have been estimated at more than $1 trillion. The latest F-35 Selected Acquisition Report speaks (in language unusual for that document) to the need to reduce those costs:

At current estimates, the projected F-35 sustainment outlays are too costly. Given planned fleet growth, future U.S. Service O&S budgets will be strained. The prime contractor must embrace much-needed supply chain management affordability initiatives, optimize priorities across the supply chain for spare and new production parts, and enable the exchange of necessary data rights to implement the required stand-up of planned government organic software capabilities. 55

A media report indicated that the Air Force was considering reducing its buy of F-35As due to the support costs. "The shortfall would force the service to subtract 590 of the fighter jets from the 1,763 it plans to order ... the Air Force faces an annual bill of about $3.8 billion a year that must be cut back over the coming decade."56 "'If you can afford to buy something but you have to keep it in the parking lot because you can't afford to own and operate it, then it doesn't do you much good,' says F-35 JPO Program Executive Officer Vice Adm. Mat Winter." 57

F-35 Program Origin and History

The Joint Strike Fighter (JSF) program that became the F-35 began in the early- to mid-1990s.58 Three different airframe designs were proposed by Boeing, Lockheed, and McDonnell Douglas (teamed with Northrop Grumman and British Aerospace.) On November 16, 1996, the Defense Department announced that Boeing and Lockheed Martin had been chosen to compete in the concept demonstration phase of the program, with Pratt and Whitney providing propulsion hardware and engineering support. Boeing and Lockheed were each awarded contracts to build and test-fly two aircraft to demonstrate their competing concepts for all three planned JSF variants.59

The competition between Boeing and Lockheed Martin was closely watched. Given the size of the JSF program and the expectation that the JSF might be the last fighter aircraft program that DOD would initiate for many years, DOD's decision on the JSF program was expected to shape the future of both U.S. tactical aviation and the U.S. tactical aircraft industrial base.

In October 2001, DOD selected the Lockheed design as the winner of the competition, and the JSF program entered the system development and demonstration (SDD) phase, with SDD contracts awarded to Lockheed Martin for the aircraft and Pratt and Whitney for the aircraft's engine. General Electric continued technical efforts related to the development of an alternate engine for competition in the program's production phase.

|

First flown |

Original IOC goal |

IOC |

|

|

F-35A |

December 15, 2006 |

March 2013 |

August 2, 2016 |

|

F-35B |

June 11, 2008 First hover: March 17, 2010 |

March 2012 |

July 31, 2015 |

|

F-35C |

June 6, 2010 |

March 2015 |

Anticipated 2019 |

Source: Prepared by CRS based on press reports and DOD testimony.

Note: IOC is Initial Operational Capability (discussed below).

As shown in Table 1, the first flights of an initial version of the F-35A and the F-35B occurred in the first quarter of FY2007 and the third quarter of FY2008, respectively. The first flight of a slightly improved version of the F-35A occurred on November 14, 2009.60 The F-35C first flew on June 6, 2010.61

The F-35B's ability to hover, scheduled for demonstration in November, 2009, was shown for the first time on March 17, 2010.62 The first vertical landing took place the next day.63

February 2010 Program Restructuring

In November 2009, DOD's Joint Estimating Team issued a report (called JET II) stating that the F-35 program would need an extra 30 months to complete the SDD phase. In response to JET II, the then-impending Nunn-McCurdy breach and other developments, on February 24, 2010, Pentagon acquisition chief Ashton Carter issued an Acquisition Decision Memorandum (ADM) restructuring the F-35 program. Key elements of the restructuring included the following:

- Extending the SDD phase by 13 months, thus delaying Milestone C (full-rate production) to November 2015 and adding an extra low-rate initial production (LRIP) lot of aircraft to be purchased during the delay. Carter proposed to make up the difference between JET II's projected 30-month delay and his 13-month schedule by adding three extra early-production aircraft to the test program. It is not clear how extra aircraft could be added promptly if production is already behind schedule.

- Funding the program to the "Revised JET II" (13-month delay) level, implicitly accepting the JET II findings as valid.

- Withholding $614 million in award fees from the contractor for poor performance, while adding incentives to produce more aircraft than planned within the new budget.

- Moving procurement funds to R&D. "More than $2.8 billion that was budgeted earlier to buy the military's next-generation fighter would instead be used to continue its development."64

"Taken together, these forecasts result in the delivery of 122 fewer aircraft over the Future Years Defense Program (FYDP), relative to the President's FY 2010 budget baseline," Carter said.65 This reduction led the Navy and Air Force to revise their dates for IOC as noted above.

March, 2010 Nunn-McCurdy Breach

On March 20, 2010, DOD formally announced that the JSF program had exceeded the cost increase limits specified in the Nunn-McCurdy cost containment law, as average procurement unit cost, in FY2002 dollars, had grown 57% to 89% over the original program baseline. Simply put, this requires the Secretary of Defense to notify Congress of the breach, present a plan to correct the program, and to certify that the program is essential to national security before it can continue.66

On June 2, 2010, the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition, Technology and Logistics issued an Acquisition Decision Memorandum (ADM) certifying the F-35 Program in accordance with section 2433a of title 10, United States Code. As required by section 2433a, of title 10, Milestone B was rescinded. A Defense Acquisition Board (DAB) was held in November 2010… No decision was rendered at the November 2010 DAB… Currently, cumulative cost and schedule pressures result in a critical Nunn-McCurdy breach to both the original (2001) and current (2007) baseline for both the Program Acquisition Unit Cost (PAUC) and Average Procurement Unit Cost (APUC). The breach is currently reported at 78.23% for the PAUC and 80.66% for the APUC against the original baseline and 27.34% for the PAUC and 31.23% for the APUC against the current baseline.67

February 2012 Procurement Stretch

With the FY2013 budget, F-35 acquisition was slowed, with the acquisition of 179 previously planned aircraft being moved to years beyond the FY2013-2017 FYDP "for a total of $15.1 billion in savings."68

Initial Operational Capability

The Marine Corps declared F-35B Initial Operational Capability (IOC) on July 31, 2015. The Air Force declared F-35A IOC on August 2, 2016.69 The Navy IOC may be delayed to 2019, which is within its projected threshhold.70

The F-35A, F-35B, and F-35C were originally scheduled to achieve IOC in March 2013, March 2012, and March 2015, respectively.71 In March, 2010, then-Pentagon acquisition chief Ashton Carter announced that the Air Force and Navy had reset their projected IOCs to 2016, while Marine projected IOC remained 2012.72 Subsequently, the Marine IOC was delayed.73

Congress required a formal declaration of IOCs in Section 155 of the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2013 (P.L. 112-239.) The current dates (by fiscal year) are shown in Table 1.

It should be noted that IOC means different things to different services:

F-35A initial operational capability (IOC) shall be declared when the first operational squadron is equipped with 12-24 aircraft, and Airmen are trained, manned, and equipped to conduct basic Close Air Support (CAS), Interdiction, and limited Suppression and Destruction of Enemy Air Defense (SEAD/DEAD) operations in a contested environment. Based on the current F-35 Joint Program Office (JPO) schedule, the F-35A will reach the IOC milestone between August 2016 (Objective) and December 2016 (Threshold)...

F-35B IOC shall be declared when the first operational squadron is equipped with 10-16 aircraft, and US Marines are trained, manned, and equipped to conduct CAS, Offensive and Defensive Counter Air, Air Interdiction, Assault Support Escort, and Armed Reconnaissance in concert with Marine Air Ground Task Force resources and capabilities. Based on the current F-35 JPO schedule, the F-35B will reach the IOC milestone between July 2015 (Objective) and December 2015 (Threshold)...

Navy F-35C IOC shall be declared when the first operational squadron is equipped with 10 aircraft, and Navy personnel are trained, manned and equipped to conduct assigned missions. Based on the current F-35 JPO schedule, the F-35C will reach the IOC milestone between August 2018 (Objective) and February 2019 (Threshold).74

Additionally,

Each of the three US services will reach initial operating capability (IOC) with different software packages.

The F-35B will go operational for the US Marines in December 2015 with the Block 2B software, while the Air Force plans on achieving IOC on the F-35A in December 2016 with Block 3I, which is essentially the same software on more powerful hardware. The Navy intends to go operational with the F-35C in February 2019, on the Block 3F software.75

One complication regarding the Navy's operational capability is that the Navy reportedly will not be able to airlift F-35 engines to carriers at sea until the introduction of the CMV-22 carrier onboard delivery aircraft in 2021.76 The Navy will not declare IOC until software Block 3F is fully proven. 77

Procurement Quantities

Planned Total Quantities

The F-35 program includes a planned total of 2,456 aircraft for the Air Force, Marine Corps, and Navy. This included 13 research and development aircraft and 2,443 production aircraft: 1,763 F-35As for the Air Force, 273 F-35Cs for the Navy, and 67 F-35Cs and 353 F-35Bs for the Marine Corps.78 79

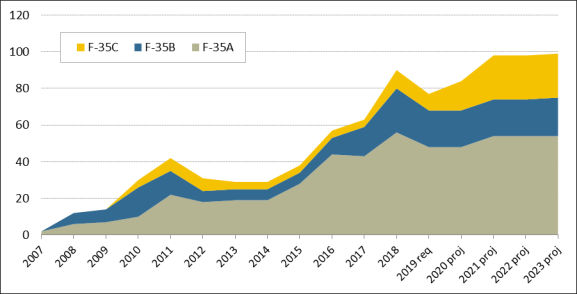

Annual Quantities

DOD began procuring F-35s in FY2007. Figure 2 shows F-35 procurement quantities authorized through FY2018, requested procurement quantities for FY2019, and projected requests through the FYDP. The figures in the table do not include 13 research and development aircraft procured with research and development funding. (Quantities for foreign buyers are discussed in the next section.)

|

Figure 2. F-35 Procurement Quantities (Figures shown are for production aircraft; table excludes 13 research and development aircraft) |

|

|

Source: Prepared by CRS based on DOD data. |

Previous DOD plans contemplated increasing the procurement rate of F-35As for the Air Force to a sustained rate of 80 aircraft per year by FY2015, and completing the planned procurement of 1,763 F-35As by about FY2034. The current Air Force plan increases the rate to 54 per year beginning in 2021; the 1,763 fleet target has not changed.

Past DOD plans also contemplated increasing the procurement rate of F-35Bs and Cs for the Marine Corps and Navy to a combined sustained rate of 50 aircraft per year by about FY2014, and completing the planned procurement of 680 F-35Bs and Cs by about FY2025. The FY2019 budget submission shows a combined F-35B and -C production rate of 44 per year in 2021, toward a fleet goal of 693.

Low-Rate Initial Production

F-35s are currently produced under Low Rate Initial Production (LRIP), with agreements reached for the first 10 lots of aircraft. Each LRIP lot includes both U.S. and international partner aircraft.

Contracted unit prices for F-35s have continued to decline with each production lot. "For example, the price (including airframe, engine and profit) of an LRIP Lot 8 aircraft was approximately 3.6 percent less than an LRIP Lot 7 aircraft, and an LRIP Lot 7 aircraft, was 4.2 percent lower than an LRIP Lot 6 aircraft." 80

In LRIPs 5, 6, and 7, any cost overruns associated with concurrent development and production would be split equally between the contractor and the government. Prior to LRIP 4, the government bore those costs alone. Beginning with LRIP 8, the contractor is liable for 100% of any cost overrun; if actual cost is lower than the contracted cost, the contractor will receive 80% of the savings, the government 20%.81

|

LRIP Lot |

5a |

6b |

8e |

9f |

10 |

|

|

F-35A quantity/cost |

22/105 |

23/103 |

19/98 |

19/95 |

42/102 |

44/95 |

|

F-35B quantity/cost |

3/113 |

7/109 |

6/104 |

6/102 |

13/132 |

9/123 |

|

F-35C quantity/cost |

7/125 |

6/120 |

4/116 |

4/116 |

2/132 |

2/122 |

Notes: Aircraft costs for LRIPs 5-8 shown do not include engines. All quantities exclude international orders.

a. Christopher Drew, "Lockheed Profit on F-35 Jets Will Rise With New Contract," The New York Times, December 17, 2012.

b. Tony Capaccio, "Lockheed Gets Approval Of Next F-35 Production Contract," Bloomberg News, July 6, 2012.

c. Amy Butler, "Latest F-35 Deal Targets Unit Cost Below $100 Million," Aviation Week & Space Technology, July 30, 2013.

d. Caitlin Lee, "Latest F-35 contracts mark new strategy to reduce costs," Jane's Defence Weekly, September 29, 2013.

e. Colin Clark, "New F-35 Prices: A: $95M; B: $102M; C: $116M," Breaking Defense, November 21, 2014.

f. Sydney J. Freedberg, Jr., "F-35 'Not Out Of Control': F-35A Prices Drop 5.5%," Breaking Defense, December 19, 2016, https://breakingdefense.com/2016/12/33483/.

g. Lockheed Martin, "Agreement Reached on Lowest Priced F-35s in Program History," press release, February 3, 2017, https://www.f35.com/news/detail/agreement-reached-on-lowest-priced-f-35s-in-program-history.

Although previous LRIP contracts had been arrived at through negotiation between the F-35 Joint Program Office and Lockheed Martin, the LRIP 9 contract was not agreed to by both sides. After prolonged negotiation, the government invoked its right to issue a unilateral contract. 82

Negotiations continue on LRIP 11, with public posturing by both sides.83

Potential Block Buy

Block buy contracts commit the government to purchasing certain quantities of aircraft over a number of years, which allows the contractor to acquire parts in greater quantity and plan workforce levels in advance, helping to reduce cost. "By purchasing supplies in economic quantities, Lockheed Martin and Pratt & Whitney estimate that 8 percent and 2.3 percent cost savings, respectively, could be achievable." 84

The F-35 program office is reportedly considering a block buy contract for international customers, and possibly for U.S. F-35s in subsequent lots. "Executing the 'block buy' would require commitments to procuring as many as 270 U.S. aircraft, as well as commitments by foreign partners to purchasing substantial numbers of aircraft." 85 Lockheed Martin expected to reveal a block buy proposal in March 2018.86 This follows on an earlier mooted block buy:

The buy would begin in low-rate, initial production (LRIP) lot 11, which includes deliveries in 2019.... The international block buy is one of multiple steps toward reducing the per-unit price of the F-35A to $80-85 million in 2019, Bogdan says.87

|

What Is Block Buy?88 Block buy contracting (BBC) permits DOD to use a single contract for more than one year's worth of procurement of a given kind of item without having to exercise a contract option for each year after the first year. It is similar to multi-year procurement in that DOD needs congressional approval for each use of BBC. BBC differs from MYP in the following ways:

|

"A full block buy, including US jets, could save anywhere from $2 billion to $2.8 billion, according to industry estimates."89 Congressional approval would be required for a U.S. block buy.90

In a related development, Section 141 of the Fiscal Year 2018 National Defense Authorization Act included language authorizing DOD to enter into economic order quantity contracts for advance parts for F-35s to be procured in FY 2019 and 2020.

Program Management

The JSF program is jointly managed and staffed by the Department of the Air Force and the Department of the Navy. Service Acquisition Executive (SAE) responsibility alternates between the two departments. When the Air Force has SAE authority, the F-35 program director is from the Navy, and vice versa. Navy Vice Admiral Mathias Winter became the F-35 program manager, succeeding Air Force Lt. Gen. Christopher Bogdan, on May 25, 2017.91

Section 146 of the FY2017 National Defense Authorization Act (P.L. 114-328) required DOD to examine alternative management structures for the F-35 program. Proponents argued that the overhead structure of a joint office, even if needed for development of a joint aircraft, is not needed once production has been established, and further that the F-35 is functionally three separate aircraft, with much less commonality than earlier envisioned. "[E]ven the Program Executive Officer of the F-35 Joint Program Office, General Christopher Bogdan, recently admitted the variants are only 20–25 percent common."92 Supporters cited the requirement by the United States to support international customers and to oversee further software and other upgrades as reasons to keep the office in place. The Joint Program Office employs 2,590 people, and the annual cost to operate it is on the order of about $70 million a year.93

In a letter to Congress accompanying that report, Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment Ellen Lord declared an intention to

begin a deliberate, conditions-based, and risk-informed transition...from the existing F-35 management structure to an eventual management structure with separate Service-run F-35A and F-35B/C program offices that are integrated with and report through the individual Military Departments.94

Specific timing of the transition, and the responsibilities to be transferred to the services, have not been announced.95 96

Software Development

You can see from its angled lines, the F-35 is a stealth aircraft designed to evade enemy radars. What you can't see is the 24 million lines of software code which turn it into a flying computer. That's what makes this plane such a big deal.97

The F-35's integration of sensors and weapons, both internally and with other aircraft, is touted as its most distinctive aspect. As that integration is primarily realized through complex software, it may not be surprising to observe that writing, validating, and debugging that software is among the program's greatest challenges. F-35 operating software is released in blocks, with additional capabilities added from one block to the next.

I'm concerned about the software, the operational software.... And I'm concerned about the ALIS [Autonomic Logistics Information System], that is another software system, basically that will provide the logistics support to the systems. – Frank Kendall, Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition, Technology & Logistics.98

|

Block |

Attributes |

Release |

|

2B |

Required for Marine IOC |

Released |

|

3i (initial) |

Required for USAF IOC |

Development complete;a release expected late 2016 |

|

3F (final) |

Required for Navy IOC |

Expected late fall 2017 |

|

4 |

Adds nuclear weapons capability (among other things) |

Development to begin late 2018 |

Source: Prepared statement of the Honorable Sean J. Stackley, Assistant Secretary Of The Navy (Research, Development and Acquisition) and Lt General Christopher C. Bogdan, Program Executive Officer, F-35 before the U.S. Congress, House Committee on Armed Services, Subcommittee on Tactical Air and Land Forces, F-35 Program review, 114th Cong., 2nd sess., March 23, 2016.

a. F-35 Joint Program Office, "Development of F-35 3i Software For USAF IOC Complete," press release, May 9, 2016, https://www.f35.com/news/detail/development-of-f-35-3i-software-for-usaf-ioc-complete.

Kendall's concern was echoed by then-F-35 program manager, Air Force Lt. Gen. Christopher Bogdan. In testimony to the House Armed Services Subcommittee on Tactical Air and Land Forces, he noted that it is the

"complexity of the software that worries us the most.... Software development is always really, really tricky... We are going to try and do things in the final block of this capability that are really hard to do." Among them is forming software that can share the same threat picture among multiple ships across the battlefield, allowing for more coordinated attacks.99

Block 4 as a Separate Program

Development of the F-35 follow-on Block 4 software, an effort now known as Continuous Capability Development and Delivery (C2D2) had been expected to cost as much as $8 billion. More recent estimates put that figure at 10.8 billion through FY 2024. Some in Congress argue that a program of that size should part with traditional procurement practice for an upgrade and be run as a separate Major Defense Acquisition Program, with its own budget line and the concomitant reporting requirements; language to this effect was included in the Senate's version of the FY2017 National Defense Authorization Act. This is discussed further in "Issues for Congress," below.

Autonomic Logistics Information System

The issues cited above focused on software development for the F-35's onboard mission systems. A supporting system, the Autonomic Logistics Information System (ALIS), also requires extensive software development and testing. "ALIS is at the core of operations, maintenance and supply-chain management for the F-35, providing a constant stream of data from the plane to supporting staff." 100

DOD's Director of Operational Test & Evaluation stated that "ALIS 3.0, planned for use in IOT&E and the completion of SDD, will likely not be ready for fielding until early to mid-CY18. ALIS version 3.0 is necessary to provide full combat capability. However, the program will likely not field ALIS 3.0 until early 2018 due to delays with ALIS 2.0.2.4. The program deferred to ALIS 4.0 capabilities previously designated for ALIS 3.0."101

ALIS may not be deployable: ALIS requires server connectivity and the necessary infrastructure to provide power to the system. The Marine Corps, which often deploys to austere locations, declared in July 2015 its ability to operate and deploy the F-35 without conducting deployability tests of ALIS. A newer version of ALIS was put into operation in the summer of 2015, but DOD has not yet completed comprehensive deployability tests.

ALIS does not have redundant infrastructure: ALIS's current design results in all F-35 data produced across the U.S. fleet to be routed to a Central Point of Entry and then to ALIS's main operating unit with no backup system or redundancy. If either of these fail, it could take the entire F-35 fleet offline.102

To date, the F-35's operators have been coping with ALIS's shortcomings. "Most capabilities function as intended only with a high level of manual effort by ALIS administrators and maintenance personnel. Manual work-arounds are often needed to complete tasks designed to be automated." 103 Some of the problems reportedly stem from ALIS's 1990s-based architecture. 104

Air Force Lt. Gen. Chris Bogdan told reporters that the plane could fly without the $16.7 billion ...ALIS for at least 30 days. The software, which runs on ground computers, not the plane itself, manages the aircraft's supply chain, aircraft configuration, fault diagnostics, mission planning, and debriefing – none of which are critical to combat flight.105

Cost and Funding106

Total Program Acquisition Cost107

As of December, 2017, the total estimated acquisition cost (the sum of development, procurement, and military construction [MilCon] costs) of the F-35 program in constant (i.e., inflation-adjusted) FY2012 dollars was about $325.1 billion, including about $59.8 billion in research and development, about $260.9 billion in procurement, and about $4.4 billion in MilCon.108

In then-year dollars (meaning dollars from various years that are not adjusted for inflation), the figures are about $406.1 billion, including about $55.5 billion in research and development, about $345.4 billion in procurement, and about $5.3 billion in military construction.

Prior-Year Funding

Through FY2017, the F-35 program has received a total of roughly $122.6 billion of funding in then-year dollars, including roughly $54.7 billion in research and development, about 65.7 billion in procurement, and approximately $2.7 billion in military construction.

Unit Costs

As of December, 2017, the F-35 program had a program acquisition unit cost (or PAUC, meaning total acquisition cost divided by the 2,456 research and development and procurement aircraft) of about $110.0 million and an average procurement unit cost (or APUC, meaning total procurement cost divided by the 2,443 production aircraft) of $89.8 million, in constant FY2012 dollars.

However, this reflects the cost of the aircraft without its engine, as the engine program was broken out as a separate reporting line in 2011.

As of December, 2017, the F-35 engine program had a program acquisition unit cost of about $21.6 million and an average procurement unit cost of $16.4 million in constant FY2012 dollars. Just as the reported airframe costs represent a program average and do not discriminate among the variants, the engine costs do not discriminate between the single engines used in the F-35A and C and the more expensive engine/lift fan combination for the F-35B.

However, beginning in December 2016, DOD's Selected Acquisition Reports broke out unit recurring flyaway costs of the three engines as well as the separate airframes, as follows:

Table 4. F-35 Projected Unit Recurring Flyaway Cost

(Includes hardware costs over the life of the program and assumes 612 international sales)

|

$M (2012) |

F-35A |

F-35B |

F-35C |

|

Airframe |

67.6 |

77.4 |

78.7 |

|

Engine |

10.9 |

26.8 |

11.1 |

|

Total |

77.5 |

104.2 |

89.8 |

Source: Office of the Secretary of Defense, Selected Acquisition Report (SAR): F-35 Joint Strike Fighter Aircraft (F-35), March 19, 2018.

Note: Previous versions of this chart assumed 2443 US sales and 673 international sales rather than 2456/612.

Critics note that the costs reported in the Selected Acquisition Reports contain a number of assumptions about future inflation rates, production learning curves, and other factors, and argue that these figures do not accurately represent the true cost of developing and acquiring the F-35.109

Other Cost Issues

Acquisition Cost and Affordability

In a recent report on the F-35 program, the Government Accountability Office questioned DOD's ability to afford the current F-35 program given other demands on budgets. This is a contrast to earlier reports, which focused more on the program's ability to meet its cost targets.

Although the estimated F-35 ... program acquisition costs have decreased since 2014, the program continues to face significant affordability challenges.... The program will require an average of $12 billion per year to complete the procurement of aircraft through 2038. The program expects to reach peak production rates for U.S. aircraft in 2022, at which point DOD expects to spend more than $14 billion a year on average for a decade... These affordability challenges will compound as the program competes with other large acquisition programs including the long range strike bomber and KC-46A Tanker. At the same time, the number of operational F-35 aircraft that DOD will have to support will be increasing. 110

Unit Cost Projections

The F-35 program continues efforts to make the F-35 cost-competitive with previous-generation aircraft. (It should be noted that the articles cited below reference the cost of the F-35A, the simplest model.)

F-35 fighter jets will sell for as little as $80 million in five years, according to the Pentagon official running the program.

"The cost of an F-35A in 2019 will be somewhere between $80 and $85 million, with an engine, with profit, with inflation," U.S. Air Force Lieutenant General Christopher Bogdan, the Pentagon's manager of the program, told reporters in Canberra today.111

That article dated from 2014. More recently, efforts have been increased to reach the same target:

[Lockheed Martin] will invest up to $170 million over the next two years to extend its existing "Blueprint for Affordability" measure ... to drive down the unit cost of an F-35A to $85 million by 2019.112

As noted in Table 4, the average unit flyaway cost of an F-35A is officially projected at $77.5 million.

Engine Costs

In 2013, engine maker Pratt & Whitney embarked on a program to reduce the F-35 engine's cost.113 Following release of data showing the "cost of acquiring the planned 2,443 airframes and associated systems rose 1%, while engine costs climbed 6.7%,"114 the program manager reportedly singled out Pratt for criticism "after having improved relations with the F-35's prime contractor, Lockheed Martin Corp., securing lower prices for each batch of new airframes and closing deals far quicker than in the past."115

Subsequently, Pratt & Whitney has signed contracts for engines through LRIP 10 that show a steady percentage decrease in cost. The LRIP 10 announcement included a figure of $1.95 billion for 99 engines, although as that includes program management, engineering support, production non-recurring efforts, spare modules and spare parts, it is not possible to derive a specific cost for each engine. "[Pratt & Whitney] is claiming competitive privilege in its sole-source deal for F-35 engines in not releasing its actual numbers."116

Pratt says that "unit prices for 86 conventional takeoff and landing (CTOL) and carrier variant (CV) propulsion systems were reduced by 2.6 percent, and unit prices for 13 LRIP 10 short takeoff and vertical landing (STOVL) propulsion systems, including Rolls-Royce Lift Systems, were reduced by 4.2 percent" compared to the previous contract.117

The issue of engine cost transparency is addressed in "Issues for Congress," below.

Anticipated Upgrade Costs

The degree of concurrency in the F-35 program, in which aircraft are being produced while the design is still being revised through testing, appears to make upgrades to early-production aircraft inevitable. The cost of those upgrades may vary, depending on what revisions are made during the testing process. However, the cost of such upgrades is not included in the negotiated price of each production lot.

The first F-35As, for example, were loaded with a basic software release (Block 1B) that provides basic aircraft control, but does not have the degree of sensor fusion or weapons integration expected in later blocks. "The initial estimate for modifying early-production F-35As from a basic configuration to a capable warfighting level is $6 million per jet, plus other associated expenses not included in that figure."118 That would make the current cost of upgrading the earliest F-35As to Block 3F about $100 million. In order to increase capability, the Air Force intends to upgrade the aircraft step-by-step as new software releases become available rather than waiting and jumping to the final release of Block 3F.

The cost of the major upgrade to Block 4 is discussed in "Issues for Congress," below.

Operating and Support Costs

Since 2015, Selected Acquisition Report projected lifetime operating and sustainment costs for the F-35 fleet have been estimated at slightly over $1 trillion,119 "which DOD officials have deemed unaffordable. The program's long term sustainment estimates reflect assumptions about key cost drivers that the program does not control, including fuel costs, labor costs, and inflation rates." 120 "The eye-popping estimate has raised hackles at the Defense Department and on Capitol Hill since it was disclosed in 2011. It covers the cost of fuel, spare parts, logistics support and repairs."121 It may be worth noting that "the F-35 was ... the first big Pentagon weapons program to be evaluated using a 50-year lifetime cost estimate—about 20 years longer than most programs—which made the program seem artificially more expensive."122

Operations and sustainment costs as of the December 2017 Selected Acquisition Report were reported at $620.8 billion in 2012 dollars (or $1.12 trillion in then-year dollars.) However, that figure had not been recalculated since FY2015; a new estimate is in progress.123 124

"The operation and sustainment cost is a bigger issue," (Air Force acquisition chief William) LaPlante said. "It's the one that will say whether or not we can afford (the F-35) in the longer run."125

Operations costs are being addressed on several fronts, including changes in training, basing, support, and other approaches.

To attack this problem, the F-35 program office in October 2013 set up a "cost war room" in Arlington, Va.... A team of government and contractor representatives assigned to the cost war room are investigating 48 different ways to reduce expenses. They are also studying options for future repair and maintenance of F-35 aircraft in the United States and abroad. 126

The U.S. Air Force is looking to slash the number of locations where it will base F-35 Joint Strike Fighter squadrons to bring down the jet's estimated trillion-dollar sustainment costs.... 'When you reduce the number of bases from 40 to the low 30s, you end up reducing your footprint, making more efficient the long-term sustainment,' David Van Buren, the service's acquisition executive, said in a March 2 exit interview at the Pentagon.127

More recently, "Lockheed, Northrop and BAE are also starting a 'sustainment cost reduction initiative' aimed at cutting operations and maintenance expenses by 10 percent during fiscal 2018 through fiscal 2022. The vendors will invest $250 million and hope to reap at least $1 billion in savings over five years."128

Manufacturing Locations

The F-35 is manufactured in several locations. Lockheed Martin builds the aircraft's forward section in Fort Worth, TX. Northrop Grumman builds the mid-section in Palmdale, CA, and the tail is built by BAE Systems in the United Kingdom.129 Final assembly of these components takes place in Fort Worth. Final assembly and checkout facilities have also been established in Cameri, Italy, and Nagoya, Japan.

The Pratt & Whitney F135 engine for the F-35 is produced in East Hartford and Middletown, CT. Rolls-Royce builds the F-35B lift system in Indianapolis, IN.

International Participation

In General

The F-35 program is DOD's largest international cooperative program. DOD has actively pursued allied participation as a way to defray some of the cost of developing and producing the aircraft, and to "prime the pump" for export sales of the aircraft.130 Allies in turn view participation the F-35 program as an affordable way to acquire a fifth-generation strike fighter, technical knowledge in areas such as stealth, and industrial opportunities for domestic firms.

Eight allied countries—the United Kingdom, Canada, Denmark, The Netherlands, Norway, Italy, Turkey, and Australia—are participating in the F-35 program under a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) for the SDD and Production, Sustainment, and Follow-On Development (PSFD) phases of the program. These eight countries have contributed varying amounts of research and development funding to the program, receiving in return various levels of participation in the program. International partners are also assisting with Initial Operational Test and Evaluation (IOT&E), a subset of SDD.131 The eight partner countries are expected to purchase hundreds of F-35s, with the United Kingdom's 138 being the largest anticipated foreign fleet.132

Two additional countries—Israel and Singapore—are security cooperation participants outside the F-35 cooperative development partnership.133 Israel has agreed to purchase 33 F-35s, and may want as many as 50.134 135 Japan chose the F-35 as its next fighter in October 2011,136 and South Korea committed to the F-35 in 2014.137 Sales to additional countries are possible. Some officials have speculated that foreign sales of F-35s might eventually surpass 2,000 or even 3,000 aircraft.138

Sales to Israel, Japan, and South Korea are conducted through the standard Foreign Military Sales process, including congressional notification. F-35 sales to nations in the consortium, conducted under 22 USC 2767, are not reviewed by Congress.139

The UK is the most significant international partner in terms of financial commitment, and the only Level 1 partner.140 On December 20, 1995, the U.S. and UK governments signed an MOU on British participation in the JSF program as a collaborative partner in the definition of requirements and aircraft design. This MOU committed the British government to contribute $200 million toward the cost of the 1997-2001 Concept Demonstration Phase.141 On January 17, 2001, the U.S. and UK governments signed an MOU finalizing the UK's participation in the SDD phase, with the UK committing to spending $2 billion, equating to about 8% of the estimated cost of SDD. A number of UK firms, such as BAE and Rolls-Royce, participate in the F-35 program.142

International Sales Quantities

The cost of F-35s for U.S. customers depends in part on the total quantity of F-35s produced. As the program has proceeded, some new customers have emerged, such as South Korea and Japan, mentioned above. Other countries have considered increasing their buys, while some have deferred previous plans to buy F-35s. It is perhaps noteworthy that the latest Selected Acquisition Reports reduced the number of assumed international sales for cost purposes from 673 to 612.143 Recent updates to other countries' purchase plans are detailed in "Changes in International Orders," above.

Other international competitions in which the F-35 is or could be a candidate include the following:

|

Nation |

Plans |

Candidates |

|

Belgium |

Looking to purchase 34 new fighters. Selection is expected in 2018, with first deliveries expected in 2023. U.S. State Department has cleared potential F-35 sale. |

Lockheed Martin F-35, Boeing F/A-18 Super Hornet, Dassault Rafale, Eurofighter Typhoon, Saab Gripen |

|

Finland |

Studying options to replace early model F/A-18 Hornets. Type selection could be made in 2020, and officials have said only Western fighters are being considered. |

Gripen believed to have an edge. |

|

Poland |

Considering what to do with its Russian-built Su-22 attack aircraft and MiG-29 fighters. Has already taken delivery of 48 F-16s. A selection for more could be made in 2022. |

Light attack version of the Leonardo-Finmeccanica M346, F-35, Typhoon |

|

Spain |

Operating Eurofighter and F/A-18 Hornet for the foreseeable future. Spain wants to replace its Hornets with an unmanned combat aircraft in the late 2020s or 2030s. |

May also have to consider F-35B to maintain a fixed-wing fast jet from its small carrier. |

|

Turkey |

Replacing F-4 Phantoms with F-35As and F-16s with a new, indigenous aircraft, the TFX, first expected to fly in 2023. BAE Systems has been selected as co-partner to develop TFX. |

Turkey also has ambitions to fly F-35Bs from its new amphibious warfare ships. |

|

Germany |

Looking to replace 85 Panavia Tornados. No formal contest announced, but the German MoD has reportedly received classified briefings on the F-35. |

Source: Tony Osborne, "Fighter Aircraft Procurement Plans Of 19 European Countries," Aviation Week, June 29, 2016, http://aviationweek.com/defense/fighter-aircraft-procurement-plans-19-european-countries-0, and Gareth Jennings, "Germany declares preference for F-35 to replace Tornado," IHS Jane's Defence Weekly, November 8, 2017, http://www.janes.com/article/75511/germany-declares-preference-for-f-35-to-replace-tornado. Edited and supplemented by CRS.

As noted, a significant question remains over whether Canada will continue as an F-35 partner. The Trudeau government repudiated the previously announced purchase of 65 (which had originally been 80.) Subsequent plans to acquire F-18s instead have been put on hold. Lockheed Martin has stated that if Canada withdraws as a customer, Canadian work share will suffer.144

Work Shares and Technology Transfer

DOD and foreign partners in the JSF program have occasionally disagreed over the issues of work shares and proprietary technology. For example, the United States rejected a South Korean request for transfer of four F-35 technologies that could assist in the development of a Korean indigenous fighter program (although 21 other technologies were approved.) 145 146

The governments of Italy and the United Kingdom have lobbied for F-35 assembly facilities to be established in their countries. In July 2010, Lockheed and the Italian firm Alenia Aeronautica reached an agreement to establish an F-35 final assembly and checkout facility at Cameri Air Base, Italy, to deliver aircraft for Italy and the Netherlands. The facility opened in July, 2013.147 A similar facility has opened in Nagoya, Japan, with the first aircraft delivered in 2017.148 149 Turkey, Norway, and the Netherlands will host engine overhaul and logistics facilities.

Proposed FY2019 Budget

Table 5 shows the Administration's FY2019 request for Air Force and Navy research and development and procurement funding for the F-35 program, along with FY2017 and FY2018 funding levels. Table 6 shows the procurement request in greater detail.

|

FY2017 |

FY2018 |

FY2019 (request) |

||||

|

Funding |

Quantity |

Funding |

Quantity |

Funding |

Quantity |

|

|

RDT&E funding |

||||||

|

Dept. of Navy |

1006.8 |

— |

550.7 |

— |

643.5 |

|

|

Air Force |

507.8 |

— |

627.5 |

— |

618.5 |

|

|

Subtotal |

1,594.6 |

— |

1,178.2 |

— |

1,262.0 |

|

|

Procurement funding |

||||||

|

Dept. of Navy |

3,974.8 |

26 |

3,723.7 |

24 |

3,884.2 |

29 |

|

Air Force |

5,198.2 |

48 |

5,393.3 |

46 |

4,914.3 |

48 |

|

Subtotal |

9,173.0 |

74 |

9,116.9 |

70 |

8,798.5 |

77 |

|

Spares |

680.8 |

542.8 |

632.0 |

|||

|

TOTAL |

11,448.3 |

74 |

10,837.9 |

70 |

10,692.5 |

77 |

Source: Program Acquisition Costs by Weapons System, Office of the Under Secretary of Defense (Comptroller)/Chief Financial Officer, February, 2018.

Note: Figures shown do not include funding for MilCon funding or research and development funding provided by other countries.

|

F-35A |

F-35B |

F-35C |

|||||||

|

Quantity |

|

|

|

||||||

|

Procurement cost |

|

|

|

||||||

|

Less previous advance procurement |

|

|

|

||||||

|

Subtotal |

|

|

|

||||||

|

Advance procurement for future aircraft |

|

|

|

||||||

|

Spares |

|

|

|

||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

Total FY19 request |

|

|

|

||||||

|

Average procurement cost per aircraft |

|

|

|

Issues for Congress

Overall Need for F-35

The F-35's cutting-edge capabilities are accompanied by significant costs. Some analysts have suggested that upgrading existing aircraft might offer sufficient capability at a lower cost, and that such an approach makes more sense in a budget-constrained environment. Others have produced or endorsed studies proposing a mix of F-35s and upgraded older platforms; yet others have called for terminating the F-35 program entirely. Congress has considered the requirement for F-35s on many occasions and has held hearings, revised funding, and added oversight language to defense bills. As the arguments for and against the F-35 change, the program matures, and/or the budgetary situation changes, Congress may wish to consider the value of possible alternatives, keeping in mind the program progress thus far, funds expended, evolving world air environment, and the value of potential capabilities unique to the F-35.

Planned Total Procurement Quantities

A potential issue for Congress concerns the total number of F-35s to be procured. As mentioned above, planned production totals for the various versions of the F-35 we left unchanged by a number of reviews. Since then, considerable new information has appeared regarding cost growth and budget constraints that may challenge the ability to maintain the expected procurement quantities. "'I think we are to the point in our budgetary situation where, if there is unanticipated cost growth, we will have to accommodate it by reducing the buy,' said Undersecretary of Defense Robert Hale, then Pentagon comptroller."150

Some observers, noting potential limits on future U.S. defense budgets, potential changes in adversary capabilities, and competing defense-spending priorities, have suggested reducing planned total procurement quantities for the F-35. A September 2009 report on future Air Force strategy, force structure, and procurement by the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments, for example, states that

[A]t some point over the next two decades, short-range, non-stealthy strike aircraft will likely have lost any meaningful deterrent and operational value as anti-access/area denial systems proliferate. They will also face major limitations in both irregular warfare and operations against nuclear-armed regional adversaries due to the increasing threat to forward air bases and the proliferation of modern air defenses. At the same time, such systems will remain over-designed – and far too expensive to operate – for low-end threats….

Reducing the Air Force plan to buy 1,763 F-35As through 2034 by just over half, to 858 F-35As, and increasing the [annual F-35A] procurement rate to end [F-35A procurement] in 2020 would be a prudent alternative. This would provide 540 combat-coded F-35As on the ramp, or thirty squadrons of F-35s[,] by 2021[, which would be] in time to allow the Air Force budget to absorb other program ramp ups[,] like NGB [the next-generation bomber].151

Block 4/C2D2 as a Separate Program

Development of the F-35 Block 4 software, part of an effort now called Continuous Capability Development and Delivery (C2D2), is expected to cost as much as $10.8 billion over the next six years.152 "The F-35 Joint Program Office (JPO) plans to transition into the next phase of development – Continuous Capability Development and Delivery (C2D2) – beginning in CY18, to address deficiencies identified in Block 3F development and to incrementally provide planned Block 4 capabilities."153

"The JPO's latest plan for F-35 follow-on modernization ... C2D2, relies heavily on agile software development—smaller, incremental updates to the F-35's software and hardware instead of one big drop, with the goal of speeding follow-on upgrades while still fixing remaining deficiencies in the Block 3F software load."154

Some in Congress argue that a program of that size should part with traditional procurement practice for an upgrade and be run as a separate Major Defense Acquisition Program (MDAP), with its own budget line and the concomitant reporting requirements. At a March 23, 2016, hearing of a House Armed Services subcommittee,

Government Accountability Office (GAO) Director of Acquisition and Sourcing Management Michael Sullivan argued that the Block 4 estimated cost justifies its management as a separate program, but F-35 Program Executive Officer (PEO) Air Force Lt. Gen. Christopher Bogdan countered that breaking it off would create an administrative burden and add to the program's price tag and schedule.155

Section 1087 of the Senate's version of the FY2017 National Defense Authorization Act (S. 2943) required the Department of Defense to treat the F–35 follow-on modernization program (Block 4 development) as a separate MDAP. An amendment to the House version of the FY2017 NDAA (H.R. 4909) to do likewise failed in markup by a vote of 28-41.156

Section 223 of the conference report on the FY2018 National Defense Authorization Act (H.Rept. 115-404, accompanying H.R. 2810) included language limiting funds to be expended on F-35 follow-on modernization (i.e., the Block 4 software) pending receipt of a previously required report that contains the basic elements of an acquisition program baseline for that modernization.

Competition

Lt. Gen. Bogdan's comments regarding the difficulty of cost control in a sole-source environment (see "Engine Costs," above) reflect a broader issue affecting defense programs as industry consolidates and fewer sources of supply are available for advanced systems.157 Congress may wish to consider the merits of maintaining competition when overseeing system procurements (for example, the use of competition to maintain cost pressure was a principal argument in favor of the F-35 alternate engine program).158 On the F-35 program, that competition could include contracting for lifecycle support.

Engine Cost Transparency

In the specific case of the F-35, Pratt & Whitney and the Joint Program Office have declined to reveal the cost per engine in each LRIP contract, replacing dollar costs with percentage savings and aggregate contract values that include items other than the engines themselves. Congress may wish to consider whether this approach is sufficient to provide useful oversight, and weigh that value against a contractor's right to protect competition-sensitive data. A possible analogue can be found in the debate over whether public disclosure of the contract value for the B-21 bomber might reveal more data than prudent, or whether that is a reasonable cost to allow proper program oversight.

Affordability and Projected Fighter Shortfalls

An additional potential issue for Congress for the F-35 program concerns the affordability of the F-35, particularly in the context of projected shortfalls in both Air Force fighters and Navy and Marine Corps strike fighters.

Although the F-35 was conceived as a relatively affordable strike fighter, some observers are concerned that in a situation of constrained DOD resources, F-35s might not be affordable in the annual quantities planned by DOD, at least not without reducing funding for other DOD programs. As the annual production rate of the F-35 increases, the program will require more than $10 billion per year in acquisition funding at the same time that DOD will face other budgetary challenges. The issue of F-35 affordability is part of a larger and long-standing issue concerning the overall affordability of DOD's tactical aircraft modernization effort, which also includes procurement of F/A-18E/Fs.159 Some observers concerned about the affordability of DOD's desired numbers of F-35s have suggested procuring upgraded F-16s as complements or substitutes for F-35As for the Air Force, and F/A-18E/Fs as complements or substitutes for F-35Cs for the Navy.160 F-35 supporters argue that F-16s and F/A-18E/Fs are less capable than the F-35, and that the F-35 is designed to have reduced life-cycle costs.

The issue of F-35 affordability occurs in the context of a projected shortfall of up to 800 Air Force fighters that was mentioned by Air Force officials in 2008,161 and a projected shortfall of more than 100 (and perhaps more than 200) Navy and Marine Corps strike fighters.162 In the interim, "in light of delays with the F-35 Lightning II Joint Strike Fighter, the U.S. Air Force is set to begin looking at which of its newer F-16s will receive structural refurbishments, avionics updates, sensor upgrades or all three."163

Implications for Industrial Base

Another potential issue for Congress regarding the F-35 program concerns its potential impact on the U.S. tactical aircraft industrial base. The award of the F-35 SDD contract to a single company (Lockheed Martin) raised concerns in Congress and elsewhere that excluding Boeing from this program would reduce that company's ability to continue designing and manufacturing fighter aircraft.164

Similar concerns regarding engine-making firms have been raised since 2006, when DOD first proposed (as part of the FY2007 budget submission) terminating the F136 alternate engine program. Some observers are concerned that that if the F136 were cancelled, General Electric would not have enough business designing and manufacturing fighter jet engines to continue competing in the future with Pratt & Whitney (the manufacturer of the F135 engine). Others argued that General Electric's considerable business in both commercial and military engines was sufficient to sustain General Electric's ability to produce this class of engine in the future.

Exports of the F-35 could also have a strong impact on the U.S. tactical aircraft industrial base through export. Most observers believe that the F-35 could potentially dominate the combat aircraft export market, much as the F-16 has. Like the F-16, the F-35 appears to be attractive because of its relatively low cost, flexible design, and promise of high performance. Competing fighters and strike fighters, including France's Rafale, Sweden's JAS Gripen, and the Eurofighter Typhoon, are positioned to challenge the F-35 in the fighter export market.

Some observers are concerned that by allowing foreign companies to participate in the F-35 program, DOD may be inadvertently opening up U.S. markets to foreign competitors who enjoy direct government subsidies. A May 2004 GAO report found that the F-35 program could "significantly impact" the U.S. and global industrial base.165 GAO found that two laws designed to protect segments of the U.S. defense industry—the Buy American Act and the Preference for Domestic Specialty Metals clause—would have no impact on decisions regarding which foreign companies would participate in the F-35 program, because DOD has decided that foreign companies that participate in the F-35 program, and which have signed reciprocal procurement agreements with DOD to promote defense cooperation, are eligible for a waiver.

Future Joint Fighter Programs

Congress consolidated the JAST and ASTOVL programs after finding "no apparent willingness or commitment by the Department to examine future needs from a joint, affordable, and integrated warfighting perspective."166 DOD states that the F-35 program "was structured from the beginning to be a model of acquisition reform, with an emphasis on jointness, technology maturation and concept demonstrations, and early cost and performance trades integral to the weapon system requirements definition process."167 A subsequent RAND Corporation study found that the fundamental concept behind the F-35 program—that of making one basic airframe serve multiple services' requirements—may have been flawed.168 Congress may wish to consider how the advantages and/or disadvantages merits of joint programs may have changed as a consequence of evolutions in warfighting technology, doctrine, and tactics.

Appendix. F-35 Key Performance Parameters

Table A-1 summarizes key performance parameters for the three versions of the F-35.

|

Source of KPP |

KPP |

F-35A |

F-35B |

F-35C |

|

Joint |

Radio frequency signature |

Very low observable |

Very low observable |

Very low observable |

|

Combat radius |

590 nm |

450 nm |

600 nm |

|

|

Sortie generation |

3 surge / 2 sustained |

4 surge / 3 sustained |

3 surge / 2 sustained |

|

|

Logistics footprint |

< 8 C-17 equivalent loads (24 PAA) |

< 8 C-17 equivalent loads (20 PAA) |

< 46,000 cubic feet, 243 short tons |

|

|

Mission reliability |

93% |

95% |

95% |

|

|

Interoperability |

Meet 100% of critical, top-level information exchange requirements; secure voice and data |

|||

|

Marine Corps |

STOVL mission performance – short-takeoff distance |

n/a |

550 feet |

n/a |

|

STOVL mission performance – vertical lift bring-back |

n/a |

2 x 1K JDAM, 2 x AIM-120, with reserve fuel |

n/a |

|

|

Navy |

Maximum approach speed |

n/a |

n/a |

145 knots |

Source: F-35 program office, October 11, 2007.

Notes: PAA is primary authorized aircraft (per squadron); vertical lift bring back is the amount of weapons with which plane can safely land.