Introduction

Songwriters are legally permitted to get paid for reproductions and public performances1 of the notes and lyrics they create (the musical works). Recording artists are legally permitted to get paid for reproductions, distributions, and certain digital performances of the recorded sound of their voices combined with instruments in some sort of medium, such as a digital file, record, or compact disc (the sound recordings).

Yet these copyright holders do not have total control over their music. For example, although Taylor Swift and her record label, Big Machine, withdrew her music from the music streaming service Spotify in 2014,2 a cover version of her album 1989 recorded by the artist Ryan Adams could be heard on the service.3 Copyright law allows Mr. Adams to perform, reproduce, and distribute Ms. Swift's musical works under certain conditions as long as he pays Ms. Swift a royalty.4 Thus, as a singer who owns the rights to her sound recordings, Ms. Swift can withdraw her own recorded music from Spotify, but as a songwriter who owns the rights to her musical works, she cannot dictate how the music service uses other recorded versions of her musical works.

The amount Ms. Swift gets paid for both her musical works and her sound recordings depends on market forces, contracts among a variety of private-sector entities, and federal laws governing copyright and competition policy. Congress wrote these laws, by and large, at a time when consumers primarily accessed music via radio broadcasts or physical media, such as sheet music and phonograph records, and when each medium offered consumers a distinct degree of control over which songs they could hear next.

With the emergence of music distribution on the internet, Congress updated some copyright laws in the 1990s. It attempted to strike a balance between combating unauthorized use of copyrighted content—a practice some refer to as "piracy"—and protecting the revenue sources of the various participants in the music industry. It applied one set of copyright provisions to digital services it viewed as akin to radio broadcasts, and another set of laws to digital services it viewed as akin to physical media. Since that time, however, music distribution has continued to evolve. In addition to streaming radio broadcasts ("webcasting") and downloading recorded albums or songs, consumers can stream individual songs on demand via music streaming services. The result, as the U.S. Copyright Office has noted, has been a "blurring of the traditional lines of exploitation."5

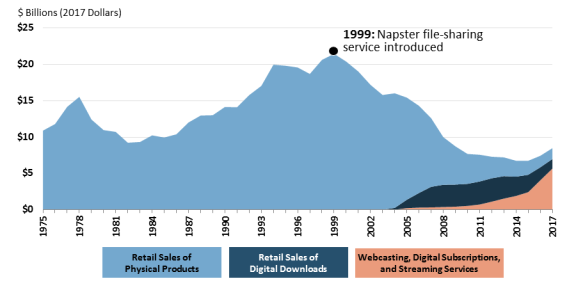

Figure 1 illustrates the evolution of music consumption over the last 40 years. In 1999, recording industry revenues reached their peak of $21.3 billion. That same year, the free Napster peer-to-peer file-sharing service was introduced.6

In 2003, after negotiating licensing agreements with all of the major record labels, Apple launched the iTunes Music Store to provide consumers a legal option for purchasing individual songs online.7 The year 2012 marked the first time the recording industry earned more from retail sales of digital downloads ($3.2 billion) than from physical media such as compact discs, cassettes, and vinyl records ($3.0 billion).8 Apple had approximately a 65% market share of digital music downloads.9

After peaking in 2012, however, sales from digital downloads began to decline, as streaming services such as Spotify, which entered the U.S. market in 2011, became more popular.10 Facing a mounting threat to its iTunes store, Apple launched its own subscription streaming music service, Apple Music, in 2015.11

The popularity of these two subscription music services has significantly altered music consumption patterns. According to the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA), the proportion of total U.S. recording industry retail spending coming from webcasting, satellite digital audio radio services and cable services (digital subscriptions), and streaming music services increased from about 9% in 2011 (out of $7.6 billion total) to about 67% in 2017 (out of $8.5 billion total). After 11 consecutive years of declining revenues, consumer spending on music was flat between 2014 and 2015, grew 10% between 2015 and 2016, and grew 14% between 2016 and 2017.12 Nevertheless, annual spending on music by U.S. consumers, adjusted for inflation, is still nearly two-thirds below its 1999 peak.13 These changing consumption patterns affect how much performers, songwriters, record companies, and music publishers get paid for the rights to their music.

|

|

Source: CRS analysis of Recording Industry Association of America Shipment Database. Notes: Inflation adjustments based on U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics Consumer Price Index. Figures do not include consumer spending on live concerts. Revenues from digital subscriptions and streaming include wholesale revenues earned by record labels and artists from licensing, rather than retail consumer spending. |

Overview of Legal Framework

Under copyright law, creators of musical works and artists who record musical works have certain legal rights. They typically license those rights to third parties, which, subject to contracts, may exercise the rights on behalf of the composer, songwriter, or performer.

Reproduction and Distribution Rights

Owners of musical works and owners of certain sound recordings possess, and may authorize others to exploit, several exclusive rights under the Copyright Act, including the following:14

- the right to reproduce the work (e.g., make multiple copies of sheet music or digital files) (17 U.S.C. §106(1))

- the right to distribute copies of the work to the public by sale or rental (17 U.S.C. §106(3))

In the context of music publishing, the combination of reproduction and distribution rights is known as a "mechanical right."15 This term dates back to the 1909 Copyright Act, when Congress required manufacturers of piano rolls and records to pay music publishing companies for the right to mechanically reproduce musical compositions.16 As a result, music publishers began issuing mechanical licenses to, and collecting mechanical royalties from, piano-roll and record manufacturers.17 While the means of reproducing music have gone through numerous changes since, including the production of vinyl records, cassette tapes, compact discs (CDs), and digital copies of songs, the term "mechanical rights" has stuck.18

For sound recordings, federal copyright protection of reproduction and distribution rights applies only to recordings originally made permanent, or "fixed,"19 after February 15, 1972.20 Works that were fixed prior to this date are protected, if at all, pursuant to a patchwork of state laws and court cases until February 15, 2067,21 but some music services have voluntarily negotiated agreements to pay royalties for use of sound recordings fixed prior to 1972.22

Public Performance Rights

The Copyright Act also gives owners of musical works and owners of sound recordings the right to "perform" works publicly (17 U.S.C. §106(4) and 17 U.S.C. §106(6), respectively). However, for sound recordings, this right applies only to digital audio transmissions. Examples of digital audio transmission services include webcasting, digital subscription services (the SiriusXM satellite digital radio service and the Music Choice cable network), and music streaming services such as Pandora and Spotify. As with sound recording reproduction and distribution rights, federal copyright laws for sound recording performance rights apply only to recordings fixed after February 15, 1972.23

Rights Required

Who pays whom, as well as who can sue whom for copyright infringement, depends in part on the mode of listening to music. Consumers of compact discs purchase the rights to listen to each song on the disc as often as they wish (in a private setting). Rights owners of sound recordings (record labels) pay music publishers for the right to record and distribute the publishers' musical works in a physical format (such as a CD or vinyl record) or digital download.24 Retail outlets that sell digital files or physical copies of sound recordings pay the distribution subsidiaries of major record labels, which act as wholesalers.25

Radio listeners have less control over when and where they listen to a song than they would if they purchased the song outright. The Copyright Act does not require broadcast radio stations to pay public performance royalties to record labels and artists, but it does require them to pay public performance royalties to music publishers and songwriters for notes and lyrics in broadcast music. As described below in "Broadcast Radio Exception," Congress appears to have concluded in 1995 that the promotional value of broadcast radio airplay outweighs any revenue lost by record labels and artists.

Digital services must pay record labels as well as music publishers for public performance rights. Both traditional broadcast radio stations and music streaming services that limit the ability of users to choose which songs they hear next (noninteractive services) make temporary copies of songs in the normal course of transmitting music to listeners.26 These temporary copies, known as "ephemeral recordings," fall under 17 U.S.C. Section 112. (For more on ephemeral recordings, see "Reproduction and Distribution Licenses.")

Users of an "on demand," or "interactive," music streaming service can listen to songs upon request, an experience similar in some ways to playing a CD and in other ways to listening to a radio broadcast. To enable multiple listeners to select songs, the services download digital files to consumers' devices. These digital reproductions are known as "conditional downloads," because consumers' ability to listen to them upon request is conditioned upon remaining subscribers to the interactive services.27 The services pay royalties to music publishers/songwriters for the right to reproduce and distribute the musical works and royalties to record labels/artists for the right to make reproductions of sound recordings.28

How the Industry Works

The music industry comprises three distinct categories of interests: (1) songwriters and music publishers; (2) recording artists and record labels; and (3) the music licensees who obtain the right to reproduce, distribute, or publicly perform music. Some entities may fall into multiple categories.

Songwriters and Music Publishers

Many songwriters, lyricists, and composers (referred to collectively as "songwriters" in this report) work with music publishers.29 On behalf of songwriters, music publishers promote songs to record labels and others who use music.30 They are also responsible for licensing the intellectual property of their clients and ensuring that royalties are collected. Under agreements between a songwriter and a publisher, the publisher may pay an advance to the songwriter against future royalty collections to help finance the songwriter's compositions. In exchange, the songwriter assigns a portion of the copyright in the compositions he or she writes during the term of the contract. The publisher's role is to monitor, promote, and generate revenue from the use of music in formats that require mechanical licensing rights, including sheet music, compact discs, digital downloads, ringtones, interactive streaming services, and broadcast radio. Publishers often contract with performing rights organizations to license and collect payment for public performances on their behalf. (See "ASCAP and BMI Consent Decree Reviews.")

Songwriters and publishers derive royalty income at each step, but may need to share this income with subpublishers and coauthors. For songwriters who are entering the music industry, the contract terms are generally standardized, with about a 50-50 division of income between the publisher and songwriter. Some songs have multiple songwriters, each with his or her own publisher, complicating the division of money.31

Music publishers fall into four general categories:32

- 1. Major Publishers. The three major publishing firms account for about 53.2% of U.S. music publishing revenue: (1) Sony/ATV Music Publishing (25.5%), (2) Universal Music Publishing Group (22.4%), and (3) Warner Music Group (5.3%).33

- 2. Major Affiliates. These independent publishing companies handle the creative aspects of songwriting management (matching writers with performing artists and record labels and helping them fine-tune their skills), while affiliating with a major publisher to handle the administration of royalties.

- 3. Independent Publishers. These firms administer their own catalogs of music, and are not affiliated with major publishers.

- 4. Writer-Publishers. Some songwriters control their own publishing rights. Examples are well-established songwriters who do not need help marketing their songs to performers and record labels, and songwriters who perform their own works. Writer-publishers may hire individuals, in lieu of companies, to administer their royalties.

Recording Artists and Record Labels

Record labels are responsible for finding musical talent, recording their work, and promoting the artists and their work. In addition, the parent companies of the three largest record labels (known as "majors") reproduce and distribute physical copies of sound recordings (compact discs and vinyl records) as well as electronic copies (MP3 files).34 The major labels have large distribution networks. Traditionally, these networks moved physical recordings from manufacturing plants into retail outlets.35

The distribution role of record labels is changing. Although the decline in consumption of physical recordings has alleviated the need to operate warehouses, the labels perform many functions with respect to selling digital copies of songs. Such functions include adding data to each recording to identify the parties entitled to royalties and keeping track of payments. In addition, they negotiate with the streaming services for the rights to use the sound recordings and monitor the sales and streaming of songs.

Similar to songwriters, recording artists may contract with a record label or retain their copyrights and distribute their own sound recordings. Recording contracts generally require recording artists to transfer their copyrights to the record label for defined periods of time and defined geographic regions.36 In return, the recording artist receives a share of royalties from sales and licenses of the sound recording. Record companies also finance recordings of music, advance funds to artists to cover expenses, and attempt to guide the artists' careers.37 Major stars who have proven their earning potential may be able to negotiate full ownership of copyrights to future sound recordings.38

Recording artists also work with independent producers to select and record material.39 Independent producers and independent labels often work with artists as subcontractors for major record companies under a variety of financial arrangements.40 Technological innovations have enabled producers to "play with" and reimagine songs written by others, leading to a blurring of the lines between producers and composers.41 (For information about proposed legislation addressing how producers get compensated for their work, see "Bills Introduced in the 115th Congress.")

The three major record labels earned about 65% of the industry's U.S. revenue: (1) Sony Corporation (14.4%), (2) Universal Music Group (29.4%), and (3) Warner Music Group (21.2%).42 Each of these labels shares a corporate parent with one of the major music publishers described in "Songwriters and Music Publishers" (Sony Corporation, Vivendi SA, and Access Industries, respectively). The publishing and recording divisions of parent companies may not necessarily both publish and record the same song.

While there are many smaller record labels specializing in genres such as country or jazz, few are truly independent, because they often rely on major record labels for the distribution of sound recordings.43 For example, Ms. Swift has a recording contract with an independent record label, Big Machine Records, which in turn has a distribution agreement with Universal Music Group.44

One recording artist who retains his copyrights and successfully distributes his own music, without signing a contract with the record label, is Chance the Rapper. Generally, instead of selling his music, Chance gives it away for free and earns money from touring and selling merchandise.45 The music streaming service Apple Music reportedly paid him $500,000 in exchange for being the exclusive outlet for his streaming-only album, Coloring Book.46 In May 2016, it became the first streaming-only album to rank among the 10 most popular U.S. albums during a week, as ranked by the trade publication Billboard.47

How Copyright Works

Songwriters and Music Publishers

Reproduction and Distribution Licenses (Mechanical Licenses)

With the 1909 Copyright Act, Congress specifically recognized the exclusive right of the copyright owner to make mechanical reproductions of music.48 The 1909 Copyright Act applied to musical works published and copyrighted after the law went into effect.

A mechanical license is a license that permits (1) the audio-only reproduction of music in copies that may be heard with the aid of "mechanical" devices such as a player piano, a phonograph record, a CD player, or a smartphone, among other devices; and (2) the distribution of such copies to the public for private use.49

When Congress considered the 1909 Copyright Act, some Members expressed concern about allegations that a large player-piano manufacturer, the Aeolian Company, was seeking to create a monopoly by buying up exclusive rights from music publishers.50 Aeolian's piano rolls did not work with the player pianos of Aeolian's competitors. Therefore, in order to be able to listen to most popular music, consumers would have to purchase Aeolian player pianos.

To address this concern, Congress established the first compulsory license in U.S. copyright law.51 A music publisher/songwriter may withhold the right to reproduce a musical work altogether. However, once a sound recording (or player-piano roll) is distributed to the public, a publisher/songwriter must allow others to make similar use of it upon payment of a specified royalty.52 Thus, in 2015, when Ryan Adams recorded a cover version of Taylor Swift's album 1989, Mr. Adams and his record label Pax-Americana Recording Company did not need to seek her permission. Instead, they paid her the rate set by the government for a compulsory mechanical license.53

The 1909 Copyright Act set the royalty rate at $0.02 per "part manufactured."54 The rate remained in place for nearly 70 years.55 Technological changes during the first half of the 20th century enabled record manufacturers to extend the amount of music on each side of a record from 5 minutes56 to more than 20 minutes,57 the number of songs per record increased, and record labels began paying mechanical royalty rates on a "per song" basis rather than per "part manufactured."58

Congress revisited the mechanical license in the Copyright Act of 1976, codifying the compulsory license as 17 U.S.C. Section 115. Congress specified that the rates would be payable for each record made and distributed [emphasis added], rather than each record manufactured.59 The 1976 Copyright Act defines the term "phonorecord" to refer to audio-only recordings.60 Since then, Congress has amended the law several times and changed the statutory rate-setting process.

Notice of Intention (NOI)

The 1976 Copyright Act also set forth procedures, codified in regulations promulgated by the Register of Copyrights, for licensees of music to obtain mechanical licenses. The licensee must serve a notice of intention (NOI) to license the music on the copyright owner, or, if the copyright owner's address is unknown, the Copyright Office.61 The licensee must file the NOI within 30 days of making the new recording or before distributing it. Licensees that cannot locate copyright owners set aside a pool of money owed until they can locate and pay the owners.62

The 1976 Copyright Act made it easier for copyright owners to sue in the following two respects:

- 1. It removed any limitation on liability and provided that a potential licensee who fails to provide the required NOI is ineligible for a compulsory license. If the potential licensee fails to obtain a negotiated license, its making and distribution of records of musical works is infringement under 17 U.S.C. Section 501 and subject to remedies provided by Sections 502-506.63

- 2. It removed the requirement that copyright holders file a "notice of use" in the Copyright Office in order to recover against an unauthorized record manufacturer.64 Instead, a copyright holder's failure to identify itself to the Copyright Office precludes the holder only from receiving royalties under a compulsory license.65 Thus, under current law, there may be no public record of the fact that the copyright owner made and distributed a copyrighted work and thereby triggered the NOI requirements.66

In contrast to the performance rights licenses, reproduction and distribution licenses are not issued on a blanket basis.67 As discussed in "Developments and Issues," NOIs and the Copyright Office's present database of musical works have led to controversy between rights holders and licensees.

Copyright Royalty Board and Ratesetting

In their 1982 article reviewing the history of the mechanical royalty, Frederick F. Greenman Jr. and Alvin Deutsch state that the idea of adjusting the statutory mechanical royalty rate periodically stemmed from a suggestion by a representative of the National Music Publishers Association (NMPA) in a 1967 hearing, who added that such adjustments should reflect the "accepted standards of statutory ratemaking."68 In testimony in 1975, then Register of Copyrights Barbara Ringer suggested that the complexity of administering the proposed compulsory licenses in addition to the mechanical license could be simplified by establishing a separate royalty tribunal, which would use standards established by Congress to set royalty rates.69

Congress created such a tribunal, consisting of five commissioners appointed by the President, in the 1976 Copyright Act.70 It also set forth in 17 U.S.C. Section 801(b)(1) four policy objectives for the tribunal to consider when determining the rates for mechanical licenses. These objectives include

- 1. maximizing the availability of public works to the public,

- 2. affording copyright owners a fair return on their creative works and copyright users a fair income under existing economic conditions,

- 3. reflecting the relative contributions of the copyright owners and users in making products available to the public, and

- 4. minimizing any disruptive impact on the structure of the industries involved and on generally prevailing industry practices.71

After replacing the tribunal with an arbitration panel in 1993, Congress established the Copyright Royalty Board (CRB) in 2004.72 The CRB, composed of three administrative judges appointed by the Librarian of Congress, sets rates every five years.73 While copyright owners and users are free to negotiate voluntary licenses that depart from the statutory rates and terms, the CRB‐set rate effectively acts as a ceiling for what an owner may charge.74

Digital Copies and Streaming Services

In 1995, Congress passed the Digital Performance Right in Sound Recordings Act (DPRA).75 Among other provisions, this act amended 17 U.S.C. Section 115 to expressly cover the reproduction and distribution of musical works by digital transmission (digital phonorecord deliveries, or DPDs).76 Congress directed that rates and terms for DPDs should distinguish between "(i) digital phonorecord deliveries where the reproduction or distribution of a phonorecord is incidental to the transmission which constitutes the digital phonorecord delivery, and (ii) digital phonorecord deliveries in general."77 This distinction prompted an extensive debate about what constitutes an "incidental DPD." For several years, the Copyright Office deferred moving forward on a rulemaking, urging that Congress resolve the matter. In July 2008, the Copyright Office proposed new rules, determining that "[while] it seems unlikely that Congress will resolve these issues in the foreseeable future ... the Office believes resolution is crucial in order for the music industry to survive in the 21st Century."78

CRB Rates

In September 2008, after nearly seven years of administrative hearings and litigation, groups representing music publishers, the recording industry, songwriters, and music streaming services reached a landmark agreement regarding the applicability of mechanical licenses to streaming.79 Music publishers had feared that as consumers shifted from purchasing music to streaming music on-demand, the revenues they received from mechanical royalties would decline.80 Based on the agreement, in the form of draft regulations to the CRB, music streaming services would pay publishers a percentage of their revenues for interactive streams and limited downloads. In addition, pursuant to the agreement, noninteractive, audio-only streaming services (e.g., Pandora) would not need to obtain mechanical licenses. The CRB adopted a modified version of this agreement in 2009, to apply through 2012.81

In 2012, groups representing music publishers, the recording industry, songwriters, and online music services reached a new agreement, subject to formal approval by the CRB, setting mechanical royalty rates and standards for five additional categories of music streaming services.82 The CRB subsequently adopted the terms of the agreement to cover rates from 2013 through 2017.83

In January 2018, the CRB issued its initial determination of mechanical royalty rates and terms for the 2018-2022 period.84 For physical phonorecord deliveries (e.g., compact discs and vinyl records) and permanent digital downloads, licensees pay a flat rate (e.g., either 9.1 cents per song or 1.75 cents per minute of playing time or fraction thereof, whichever amount is larger).85

For interactive streaming, the rates are based on a set of formulas, taking into account the music service's revenues or total costs of licensing content (including the cost of licensing sound recording). Using the formulas, the services calculate the pool of money available for distribution to publishers for mechanical royalty payments. The amount of money each publisher receives for each song is based on another set of formulas. The rate formulas also set minimum per-subscriber payments, depending on the category of interactive music service. During free trial periods (e.g., during a three-month trial subscription to Apple Music), the mechanical royalty rate is zero.

Harry Fox Agency and Music Reports, Inc.

In the United States, music publishers collect mechanical royalties from recorded music companies and streaming services via third-party administrators. The two major administrators are the Harry Fox Agency, a nonexclusive licensing agent, and Music Reports, Inc. After charging an administrative fee, these agencies distribute the mechanical royalties to the publishers, which in turn distribute them to songwriters. In September 2015, the performing rights organization Society of European Stage Authors and Composers (SESAC) acquired the Harry Fox Agency from the National Music Publishers Association trade organization.86 (For a description of SESAC and other performing rights organizations, see "Musical Work Public Performance Royalties.") Music publishers may also issue and administer mechanical licenses themselves.87

Musical Work Public Performance Royalties

Depending on who collects public performance royalties on behalf of publishers and songwriters, the rates are either subject to oversight by the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York or are based on marketplace negotiations between the publishers and licensees.

Congress granted songwriters the exclusive right to publicly perform their works in 1897.88 Thus, in order to legally publicly perform songwriters' works, establishments that featured orchestras and bands, operas, concerts, and musical comedies needed to obtain permission from songwriters and/or publishers.89 While this right represented a way for copyright owners to profit from their musical works, the sheer number and fleeting nature of public performances made it impossible for copyright owners to individually negotiate with each user for every use or to detect every case of infringement.90

To address the logistical issue of how to license and collect payment for public performances in a wide range of settings, several composers formed the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP) in 1914.91 ASCAP is known as a performance rights organization (PRO). Songwriters and publishers assign PROs the public performance rights secured by copyright law; the PROs in turn issue public performance licenses on behalf of songwriters and publishers.92 Most commonly, licensees obtain a blanket license, which allows the licensee to publicly perform any of the musical works in a PRO's catalog for a flat fee or a percentage of total revenues. After charging an administrative fee, PROs split the public performance royalties they collect among the publishers and songwriters.

In 1930, an immigrant musician founded a competing PRO, SESAC (originally called the Society of European Stage Authors and Composers), to help European publishers and writers collect royalties from U.S. licensees.93 As broadcast radio grew more popular in the United States, SESAC expanded its representation to include U.S. composers as well.

Growth in radio, as well as declining sales in sheet music and other traditional revenue sources for publishers, also prompted action from ASCAP.94 In 1932, ASCAP negotiated a public performance license with radio broadcasters that, for the first time, established rates based on a percentage of each station's advertising revenues.95 To strengthen their bargaining power vis-à-vis ASCAP, broadcasters in 1939 founded and financed a third PRO, Broadcast Music, Inc. (BMI), with the goal of attracting new composers as members and securing copyrights of new songs.96 In addition, BMI successfully convinced publishers previously affiliated with ASCAP to switch.97 [A fourth PRO, Global Music Rights [GMR], was established in 2013.)

ASCAP and BMI originally acquired the exclusive right to negotiate on behalf of their members (music publishers and songwriters) and forbade members from entering into direct licensing agreements.98 Both offered music services only blanket licenses covering all songs in their respective catalogs. When the five-year licensing agreement between ASCAP and radio stations affiliated with the CBS and NBC radio networks expired in December 1940, three-quarters of the 800 radio stations then in existence adopted a policy prohibiting the broadcast of songs by composers affiliated with ASCAP due to disagreement over royalty rates.99

DOJ Consent Decrees

The dispute between the broadcast stations and the PROs led the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) to investigate whether the PROs were violating antitrust laws.100 To avert an antitrust lawsuit threatened by DOJ, BMI agreed to enter a consent decree in 1941.101 After DOJ filed an antitrust lawsuit against ASCAP, ASCAP also agreed to enter a consent decree in 1941.102

Although the ASCAP and BMI consent decrees are not identical, they share many of the same features. Among those features are requirements that the PROs may acquire only nonexclusive rights to license members' public performance rights; must grant a license to any user that applies on terms that do not discriminate against similarly situated licensees; and must accept any songwriter or music publisher that applies to be a member, as long as the writer or publisher meets certain minimum standards. ASCAP and BMI are also required to offer alternative licenses to the blanket license. Prospective licensees that are unable to agree to a royalty rate with ASCAP or BMI may seek a determination of a reasonable license fee from one of two federal district court judges in the Southern District of New York.

In contrast to the mechanical right, the public performance of musical works is not bound by compulsory licensing under the Copyright Act. While the rates charged by ASCAP and BMI are subject to oversight by the federal district court judges, pursuant to their respective consent decrees, the rates charged by SESAC and GMR are based on marketplace negotiations.

When approving of rates charged by ASCAP and BMI, the federal district court must determine that the PROs have demonstrated that the rates are "reasonable."103 According to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, the federal district court must also consider that ASCAP and BMI exercise "disproportionate power over the market for music rights."104

Current law, 17 U.S.C. Section 114(i), prohibits the judges from considering rates paid by digital services to record labels and artists for public performances of sound recordings when setting or adjusting public performance rates payable to music publishers and songwriters. This provision was included when Congress created a public performance right for sound recordings transmitted by digital services with the 1995 passage of the DPRA. (See "Sound Recording Public Performance Royalties.")105 According to a report of the House Judiciary Committee, Congress sought to "dispel the fear that license fees for sound recordings may adversely affect music performance royalties."106 Billboard magazine described the concern among writers and publishers as the "pie theory": once digital services began to pay a public performance licensing fee for sound recordings, they might claim that they have less money available to pay for public performances of musical works.107

Since entering into these consent decrees, DOJ has periodically reviewed their operation and effectiveness. The ASCAP consent decree was last amended in 2001, and the BMI consent decree was last amended in 1994. As described in "ASCAP and BMI Consent Decree Reviews," DOJ completed a review of the consent decrees in 2016. In 2017, the Second Circuit Court of Appeals upheld BMI's challenge to DOJ's interpretation of the consent decrees.

Recording Artists and Record Labels

Reproduction and Distribution Licenses

Congress first created copyright laws that specifically applied to sound recordings with enactment of the 1971 Sound Recording Act, P.L. 92-140. The prevalence of audiotapes and audiotape recorders in the 1960s made it easier for the public to create and sell unauthorized duplications of sound recordings.108 According to the House Judiciary Committee report, the best solution for combating the trend was to amend federal copyright laws.109

The 1971 Sound Recording Act applied to sound recordings fixed on or after February 15, 1972. The following year, the U.S. Supreme Court held that neither federal copyright law nor the Constitution preempted California's record piracy law, as it applied to pre-1972 sound recordings.110 Subsequently, several states passed their own antipiracy laws. In 1975, in a hearing leading up to passage of the 1976 Copyright Act, the U.S. Department of Justice recommended that federal copyright laws exclude pre-1972 sound recordings to preserve the antipiracy laws then in effect.111 The House Judiciary Committee also noted that absent such exclusion, many works would have automatically come into the "public domain." A work of authorship is in the "public domain" if it is no longer under copyright protection and therefore may be used freely without the permission of the former copyright owner.

The 1976 Copyright Revision Act preempted state laws that provided rights equivalent to copyright, but exempted the pre-1972 works from federal protection.112 States may continue to protect pre-1972 sound recordings until 2067, at which time all state protection is to be preempted by federal law and pre-1972 sound recordings are to enter the public domain.

Recognizing that noninteractive digital services may need to make ephemeral server reproductions of sound recordings, in 1998 Congress established a related license under Section 112 of the Copyright Act specifically to authorize the creation of these copies. The rules governing licenses for temporary reproductions of sound recordings are somewhat analogous to those governing incidental reproduction and distribution of musical works described in Section 115(c)(3)(C)(i).113 The rates and terms of the Section 112 license are established by the CRB. Through SoundExchange, described below in "Sound Recording Public Performance Royalties," copyright owners of sound recordings (usually the record labels) receive Section 112 fees. Recording artists who do not own the copyrights, however, do not.114

Sound Recording Public Performance Royalties

Noninteractive Services

Until the 1990s, the Copyright Act did not afford public performance rights to record labels and recording artists for their sound recordings. Record labels and artists primarily earned income from retail sales of physical products such as CDs. With the inception and public use of the internet in the early 1990s, the recording industry once again became concerned that existing copyright law was insufficient to protect the industry from music piracy.115 Two amendments to the Copyright Act, the Digital Performance Right in Sound Recordings Act (DPRA) in 1995 and the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) in 1998, addressed this concern.116

In the DPRA, Congress granted record labels and recording artists an exclusive public performance right for their sound recordings, but limited this right to certain digital audio services. The DPRA also created a compulsory license that compelled copyright owners to license sound recordings for certain subscription services (e.g., Music Choice's music channels available to cable television subscribers).117 According to Billboard magazine, music publishers and writers were apprehensive that if record companies had the ability to withhold licenses of sound recordings from multiple outlets, they could effectively thwart the ability of publishers and writers to earn their own public performance royalties.118 The provision thus represented a compromise between trade groups representing music publishers and record labels.119

Within two years after the DRPA's enactment, the Recording Industry Association of America and nonsubscription, advertising-supported, noninteractive streaming service providers debated whether or not (1) the compulsory license applied to those services, and (2) whether the services were obligated to pay public performance royalties for sound recordings.120 After RIAA and a group representing digital music services, Digital Music Association, reached a compromise, Congress adopted the DMCA.

The DMCA expanded the statutory licensing provisions in Section 114 to cover noninteractive online music services.121 It also set up the following bifurcated system of rate-setting standards for the CRB:

- Services that existed as of July 31, 1998, prior to the enactment of the DMCA (SiriusXM satellite digital radio service as well as the Music Choice and Muzak subscription services), remained subject to the Section 801(b)(1) standard.

- Webcasters and other noninteractive music streaming services (including both subscription and advertising-supported music streaming services) that entered the music marketplace after July 31, 1998, are subject to rates and terms "that most clearly represent the rates and terms that would have been negotiated in the marketplace between a willing buyer and a willing seller."122

One key difference between the two rate-setting standards is the Section 801(b)(1) standard's inclusion of the policy goal of "minimizing any disruptive impact on the structure of the industries involved and on generally prevailing industry practices." According to a 2010 report from the Government Accountability Office, this standard led to lower copyright royalty rates in one proceeding, but the overall effect is generally difficult to predict.123 The conference report stated the purpose of applying the Section 801(b)(1) rate-setting standard services in existence prior to July 31, 1998, was to prevent disruption of the services' existing operations.124

Interactive Services

The DPRA enabled owners of the rights to sound recordings to negotiate directly with interactive music streaming services for public performance rights at marketplace-determined rates. The term "interactive service" covers only services that enable an individual to arrange for the transmission or retransmission of a specific recording.

The Senate Judiciary Committee in 1995 explained that

[C]ertain types of subscription and interactive audio services might adversely affect sales of sound recordings and erode copyright owners' ability to control and be paid for use of their work.... Of all of the new forms of digital transmission services, interactive services are the most likely to have a significant impact on traditional record sales, and therefore pose the greatest threat to the livelihoods of those whose income depends on revenues derived from traditional record sales.125

Broadcast Radio Exception

Congress does not require broadcast radio stations to obtain public performance licenses from owners of sound recordings. The Senate Judiciary Committee explained in 1995 that it was attempting to strike a balance among many interested parties. Specifically, the committee stated that

the sale of many sound recordings and the careers of many performers have benefitted considerably from airplay and other promotional activities provided by ... free over-the-air broadcast ... [and] the radio industry has grown and prospered with the availability and use of prerecorded music. This legislation should do nothing to change or jeopardize [these industries'] mutually beneficial relationship.126

The Senate Judiciary Committee further distinguished broadcast radio from other services by stating that "free over-the-air broadcasts ... provide a mix of entertainment and non-entertainment programming and other public interest activities to local communities to fulfill a condition of the broadcasters' licenses."127

Copyright Royalty Board Rate Proceedings

The CRB sets statutory rates through rate determination proceedings.128 Participants generally include copyright users, copyright holders, and trade or other groups representing their respective interests.129 The proceedings include an initial three-month period during which parties may engage in voluntary negotiations. In the absence of an agreement during that period, participants submit written statements, conduct discovery, and attempt again to reach a negotiated settlement.

At any time during the rate-setting proceeding, some or all participants may reach agreements regarding what they consider to be appropriate statutory rates. They then submit the proposed rates to the CRB, which in turn publishes the proposed rates to allow potentially affected parties to comment. The CRB may adopt and codify the proposed rates but also has the option to "decline to adopt the agreement as a basis for statutory terms and rates for participants that are not parties to the agreement."130

If the parties do not reach an agreement, the CRB generally hears live testimony at an evidentiary hearing, and subsequently issues a determination published in the Federal Register. Participants who disagree with the outcome can request a rehearing, which the CRB may choose to grant or deny. In addition, participants may challenge CRB determinations through an appeal filed with the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit.

SoundExchange

Congress provided antitrust exemptions to statutory licensees and to copyright owners of sound recordings, such as record labels, so that they could designate common agents to negotiate collectively with webcasters, SiriusXM, pre-existing subscription services, and noninteractive streaming services over royalty rates for public performance rights.131 RIAA established SoundExchange as a designated common agent for the record labels in 2000 and spun it off in 2003 as an independent entity. In 2015, SoundExchange reached agreements with public radio stations and college radio stations covering the rates paid to webcast. The CRB approved the agreements and made them binding on all copyright owners and performers, including those that are not SoundExchange members.132 Prior to distributing royalty payments, SoundExchange deducts costs incurred in carrying out its responsibilities.

Webcaster Settlement Acts

In general, using the "willing buyer-willing seller" standard, the CRB has adopted "per‐performance" rates for public performances of sound recordings by online music services. In contrast, using the Section 801(b)(1) standard, the CRB has adopted percentage‐of‐revenue rates for public performances of sound recordings by pre-existing subscription services (Music Choice and Muzak) and satellite digital audio services (SiriusXM).133

Following complaints by some music streaming services and webcasters that the per‐performance rates ordered by the CRB were excessive, Congress has repeatedly passed legislation (collectively, the "Webcaster Settlement Acts") giving SoundExchange temporary authority to negotiate alternative royalty schemes binding on all copyright owners in lieu of the CRB‐set rates.134 The agreements enabled the music streaming services to pay royalties based on a percentage of their revenue in lieu of a "per-performance" rate. The most recent agreements reached pursuant to this temporary negotiating authority expired on December 31, 2015.135

CRB Rates

In April 2015, the CRB began the hearing phase of its proceeding to set the royalty rates paid by noninteractive music streaming services for the years 2016-2020.136 In 17 U.S.C. Section 114(f)(5)(C), the CRB was barred from taking into consideration the provisions of agreements negotiated pursuant to the Webcaster Settlement Acts. During the CRB's rate proceeding, questions arose about the proper interpretation of this provision. Pandora Media, Inc., Clear Channel (now known as iHeartMedia, Inc.), and SoundExchange disagreed over whether the direct agreements, which were based in part on the Pureplay settlement, could be introduced as evidence in the CRB rate proceeding. SoundExchange argued that Congress enacted a "very broad rule of exclusion" to prevent the terms of a Webcaster Settlement Act agreement from being used against a settling party in subsequent proceedings. Pandora Media and Clear Channel contended that SoundExchange's interpretation would require disregarding every benchmark agreement proposed by parties, as all agreements are to some degree affected by the prevailing rates and terms negotiated pursuant to the 2009 Webcaster Settlement Act agreement.137 The CRB determined that these questions were novel material questions of substantive law and, as required by the Copyright Act, referred them to the Register of Copyrights for resolution.138 In September 2015, the Register ruled that the CRB may consider directly negotiated licenses that incorporate or otherwise reflect provisions in a Webcaster Settlement Act agreement.139

On December 16, 2015, the CRB issued its decision regarding rates for the 2016-2020 period.140 For 2016, streaming services (including those of broadcast radio stations as well as Pandora) must pay $0.17 per 100 streams on nonsubscription services.141 In a break from its past practice of setting rate increases in advance, the CRB tied the annual rate increases from 2017 through 2020 to the Consumer Price Index. Rather than setting forth ephemeral recording fees separately, the CRB includes them with the Section 114 royalties. For the 2016-2020 period, the CRB set ephemeral royalties fees at 5% of the total Section 114 royalties paid by streaming services.

On December 14, 2017, the CRB issued its rate decision for pre-existing digital subscription services and satellite digital audio radio services covering the 2018-2022 period.142 Table 1 describes how public performance rates vary, depending on the type of music service and when it began operating, and the rate-setting standard used by CRB.

Table 1. Royalty Rates Payable to Record Labels for Public Performance Rights

Applies to Selected Digital Noninteractive Music Services

|

Music Service Type |

% or Flat Fees |

Monthly Fees |

Notes |

|

Preexisting subscription service as of July 31, 1998 (Music Choice and Muzak) |

7.5% of gross revenues |

Not applicable |

Rate set by CRB based on 17 U.S.C. §801(b)(1) standard. Rate effective as of January 1, 2018. |

|

Preexisting satellite digital audio radio service as of July 31, 1998 (SiriusXM) |

15.5% of gross revenues |

Not applicable |

Rate set by CRB based on 17 U.S.C. §801(b)(1) standard. Rate effective as of January 1, 2018. |

|

Services providing audio-only digital music programming via residential televisions using cable or satellite television providers in operation after 1998 |

Annual minimum fee = $100,000 |

Services operating with stand-alone contracts: $0.019 per subscriber Services operating with bundled contracts with cable or satellite operator: $0.0317 per subscriber |

Rate set by CRB based on willing seller/willing buyer standard. Rate effective as of January 1, 2018. |

|

Commercial webcasters (including broadcasters simulcasting an AM or FM transmission and/or "internet-only" webcasters) |

Minimum fee of $500 per channel or station, with maximum aggregate minimum fee of $50,000 Ephemeral reproduction rates = 5% of total fee payable |

$0.0018 per performance for nonsubscription services; $0.0023 per performance for subscription services |

Rate set by CRB based on willing seller/willing buyer standard. CRB bases royalty fees increases from 2017 through 2020 on the Consumer price Index. Rate effective as of January 1, 2018. |

Sources: 37 C.F.R. §380.10; Copyright Royalty Board, "Current Developments," https://www.crb.gov/; SoundExchange, "Service Provider: 2018 Rates," https://www.soundexchange.com/service-provider/rates/.

Allocation of Royalty Distributions

The Copyright Act specifies how royalties collected under Section 114 are to be distributed: 50% goes to the copyright owner of the sound recording, typically a record label; 45% goes to the featured recording artist or artists; 2.5% goes to an agent representing nonfeatured musicians; and 2.5% goes to an agent representing nonfeatured vocalists.143

The act does not, however, include record producers in the statutorily defined split of royalties for public performances of sound recordings by noninteractive digital services. As a result, record producers must rely on contracts with one of the parties specified in the statute, often the featured recording artist, in order to receive royalties from digital performances.

Developments and Issues

"Interactive" Versus "Noninteractive" Music Services

The distinction between interactive and noninteractive services has been a matter of debate.144 For the purposes of defining the process by which owners of sound recordings can set rates for public performance rights, 17 U.S.C. Section 114 provides that an interactive service is one that enables a member of the public to receive either "a transmission of a program specially created for the recipient," or, "on request, a transmission of a particular sound recording, whether or not as part of a program, which is selected by or on behalf of the recipient."145 As discussed in "Reproduction and Distribution Licenses (Mechanical Licenses)," 17 U.S.C. Section 115 does not distinguish between interactive and noninteractive services for the purposes of specifying when a digital service must obtain mechanical rights from music publishers. The CRB has adopted these distinctions in setting or approving rates for mechanical licenses.146

In 2009, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit ruled that a music streaming service that relies on user feedback to play a personalized selection of songs that are within a particular genre or similar to a particular song or artist the user selects is not an "interactive" service.147 Noting that Congress's original intent in making the distinction was to protect sound recording copyright holders from cannibalization of their record sales, the court's decision rested on the following analysis:

If a user has sufficient control over an interactive service such that she can predict the songs she will hear, much as she would if she owned the music herself and could play each song at will, she will have no need to purchase the music she wishes to hear. Therefore, part and parcel of the concern about a diminution in record sales is the concern that an interactive service provides a degree of predictability—based on choices made by the user—that approximates the predictability the music listener seeks when purchasing music.148

The court noted that the LAUNCHcast online radio service offered by the defendant, Launch Media, Inc., which at the time was owned by Yahoo!, Inc., created unique playlists for each of its users.149 Nevertheless, the court reasoned that uniquely created playlists do not ensure predictability. Therefore, the court determined, LAUNCHcast was a noninteractive service.150

In addition, in order to be eligible for compulsory licensing, noninteractive services (other than broadcast radio, SiriusXM, Music Choice, and Muzak) must limit the features they offer consumers, pursuant to the Copyright Act. For example, these services are prohibited from announcing in advance when they will play a specific song, album, or artist. Another example is the "sound recording performance complement," which limits the number of tracks from a single album or by a particular artist that a service may play during a three‐hour period.151

The Launch Media decision affirmed that personalized music streaming services such as Pandora and iHeartRadio could obtain statutory licenses as noninteractive services for their public performances of sound recordings.152 The CRB‐established rates do not currently distinguish between such customized services and other services that simply transmit undifferentiated, radio‐style programming over the internet.

Spotify's services, on the other hand, allow users access to specific albums, songs, and artists on demand. For no charge, consumers can have limited access to songs if they use the site on their personal computers and see or hear an advertisement every few songs. In exchange for paying a monthly fee of about $10, users can listen to songs without advertisement interruption, use Spotify on mobile devices as well as personal computers, or listen to music offline.

Equity Interests in Music Services

Noncash considerations may be involved in determining the price interactive services pay for access to music. For example, the major labels acquired a reported combined 18% equity stake in Spotify in a transaction that reportedly hinged on their willingness to grant Spotify rights to use their sound recordings on its service.153 When Spotify began trading its shares on the New York Stock Exchange in April 2018, Sony sold a portion of its stake, and announced that it would share a portion of its proceeds with artists and the independent labels whose music Sony distributes.154

As described in "Reproduction and Distribution Licenses (Mechanical Licenses)," the rates that interactive services pay music publishers are tied to the rates that the services pay record labels for performance rights, which are negotiated in the free market. This means that if a record label's deal includes an equity stake in an interactive digital music service provider or a guaranteed allotment of advertising revenues, those items are assigned a value when estimating the total cost, thereby enabling music publishers to participate in such deals when negotiating for mechanical royalties.155 In contrast, copyright law prohibits rates paid for public performances of musical works from being tied to rates paid for public performances of sound recordings (see "DOJ Consent Decrees").

Organizations representing songwriters and recording artists have expressed concern that payments received by music publishers and record labels from digital music services as part of direct deals are not being shared fairly, potentially resulting in lower payments than they might receive under statutory licensing schemes.156

ASCAP and BMI Consent Decree Reviews

Together, ASCAP and BMI, which operate on a not-for-profit basis, represent about 90% of songs available for licensing in the United States.157 SESAC appears to have about a 5% share of songs, but it may be higher. Global Music Rights handles performance rights licensing for a limited number of songwriters.158 Music publishers may affiliate with multiple PROs; songwriters, however, may choose only one.159

Publishers have alleged that they have not received a fair share of the performance royalty revenues from streaming services, claiming that the ASCAP and BMI consent decrees (discussed in "DOJ Consent Decrees") inhibited their ability to negotiate market rates.160 Beginning in 2011, publishers began pressuring ASCAP and BMI to allow them to withdraw their digital rights from their blanket licenses so that they could negotiate deals directly with digital services.161

Attempts to Partially Withdraw Public Performance Rights

In 2011 and 2013, respectively, ASCAP and BMI each responded by amending their rules to allow music publishers the right to license their public performance rights for "new media" uses—that is, both interactive and noninteractive digital streaming services, so they could negotiate with digital streaming services at market prices in lieu of rates subject to oversight by the federal district court. Pandora Media, Inc., however, challenged the publishers' partial withdrawal of rights before both the ASCAP and BMI rate courts in the Southern District of New York. In each case—though applying slightly differing logic—the courts ruled that under the terms of the consent decrees, music publishers could not withdraw selected rights; rather, a publisher's song catalog must be either "all in" or "all out" of the PRO.162

After the rulings, the major music publishers and PROs asked the Department of Justice to join them in proposing modifications to the consent decrees.163 Specifically, both ASCAP and BMI sought to modify the consent decrees to permit partial grants of rights, to replace the current rate-setting process with expedited arbitration, and to allow ASCAP and BMI to provide bundled licenses that include multiple rights (e.g., mechanical as well as public performance of musical works). DOJ announced in June 2014 that it would evaluate the consent decrees.

As part of that review, it solicited comments in 2015 about "100% licensing" versus "fractional licensing."164 Industry practice has been that when a song has several writers, each writer's publisher licenses only a portion of a song, a practice known as "fractional licensing." If, as DOJ proposed, the consent decrees required 100% licensing, any writer or rights holder of a musical work could issue a performance license without the consent of the other rights holders.165

DOJ Interpretation of Consent Decrees and Lawsuits

On August 4, 2016, DOJ completed its review and announced that, pursuant to its interpretation, the consent decrees required the two PROs to issue 100% licenses to all of the songs in their catalogs.166 DOJ argued that this requirement promotes competition. It declined to propose modifications to the consent decrees, but called on Congress to reconsider how copyright law is applied to the music industry. It noted that the consent decrees are "limited in scope," and contended that "a more comprehensive legislative solution may be possible and preferable."167

The same day that DOJ issued its interpretation, BMI filed a lawsuit in the Southern District of New York, where Judge Louis Stanton is on permanent assignment overseeing the BMI consent decree.168 In September 2017, Judge Stanton ruled that contrary to the DOJ's interpretation, BMI's consent decree permits fractional licensing. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit upheld Judge Stanton's decision in December 2017.169

NOIs, Mechanical Licensing Databases, and Lawsuits

As discussed in "Notice of Intention (NOI)," a licensee must serve an NOI to the copyright holder before or within 30 days after making, and before distributing, any phonorecords, and pay the applicable royalties.170 If the Copyright Office's records do not identify the copyright owner and include an address at which the NOI can be served, then filing the NOI with the Copyright Office is sufficient.

On April 12, 2016, the Copyright Office announced new procedures to allow licensees to file Notices of Intention to reproduce and distribute musical works under Section 115 (NOIs) with the Copyright Office in bulk electronic form.171 By allowing licensees to file an NOI for up to 100 songs at once, the procedural change significantly reduced the filing costs (from $2 per song to $0.10 per song, in addition to an upfront fee of $75 for each NOI).

One week after the Copyright Office changed its NOI filing procedures, licensees, including Spotify, Amazon, and Google, began to file NOIs in bulk.172 In several NOIs, the licensees affirm that "with respect to the nondramatic musical work named in such row of this Notice of Intention, the registration records or other public records of the Copyright Office have been searched and found not to identify the name and address of the copyright owners of such work."

According to the trade publication Billboard, digital music service companies contacted the U.S. Copyright Office in late 2015, arguing that digitizing the compulsory licensing process would ensure that songwriters and publishers receive proper compensation.173 Prior to that point, several songwriters and publishers filed lawsuits charging Spotify and other online music services with illegally streaming their copyrighted musical works.174 Some of these lawsuits have been settled; others remain pending.175

Bills Introduced in the 115th Congress

Legislators have introduced several measures related to the music industry.

In January 2017, Senator John Barrasso introduced S.Con.Res. 6 and Representative Michael Conaway introduced H.Con.Res. 13, Supporting the Local Radio Freedom Act. The resolutions declare that Congress should not impose any new performance fee, tax, royalty, or other charge relating to the public performance of sound recordings on a local radio station for broadcasting sound recordings over the air, or on any business for such public performance of sound recordings.

In February 2017, Representative Joseph Crowley introduced the Allocation for Music Producers Act (AMP Act), H.R. 881. The AMP Act would grant producers the statutory right to seek payment of their royalties via a designated agent (i.e., SoundExchange) when they have a letter of direction from a featured artist.

In March 2017, Representative Jerrold Nadler introduced the Fair Play Fair Pay Act of 2017, H.R. 1836. The bill would adopt several of the Copyright Office's proposals with respect to sound recording royalties. These include (1) extending the public performance right in sound recordings to broadcast radio (with a cap on payments made by small broadcasters, public and educational radio, religious services, and incidental uses of music); (2) including sound recordings made prior to February 15, 1972, among the body of works requiring royalty payments under federal law (and continuing to rely on state law for copyright protection); and (3) directing the CRB to adopt a uniform market-based rate-setting standard for public performance rights for all types of music services (thus eliminating the §801(b)(1) four factors test). In determining the rates, the CRB would have to consider whether the audio services would enhance or interfere with the copyright owner's other sources of revenue.

In April 2017, Representative Darrell Issa introduced the Performance Royalty Owners of Music Opportunity to Earn Act of 2017 (PROMOTE Act of 2017), H.R. 1914. The bill would give copyright owners of sound recordings the exclusive right to withdraw their music from broadcast radio stations. Broadcast radio stations may "perform" sound recordings without copyright owners' permission if (1) they pay royalties identical to those paid under the statutory license rates determined by the CRB for eligible nonsubscription transmission services that apply to digital internet radio streaming and webcasts; (2) the broadcast is of a religious service, by an educational terrestrial radio station, or by a low-power FM radio station; or (3) the broadcast is an incidental use.

In July 2017, Representative Issa introduced the Compensating Legacy Artists for Their Songs, Service, and Important Contributions to Society (CLASSICS) Act, H.R. 3301. Senator Christopher Coons introduced an identical bill, S. 2393, in February 2018. The bills would ensure that copyright owners of sound recordings made prior to February 15, 1972, would receive the same federal copyright protection parity as copyright owners of sound recordings made after that date.

Also in July 2017, Representative Jim Sensenbrenner introduced the Transparency in Music Licensing and Ownership Act, H.R. 3350. The bill would direct the Register of Copyrights to create and maintain a searchable database for musical works and sound recordings. The bill would also restrict remedies available to copyright owners if they fail to provide or maintain the minimum information required in the database.

In October 2017, Representative Hakeem Jeffries introduced the Copyright Alternative in Small-Claims Enforcement (CASE) Act of 2017, H.R. 3945. The bill would establish a Copyright Claims Board, an alternative forum to U.S. district courts, for copyright owners to protect their work from infringement. Participation would be voluntary. The board would be housed within the Copyright Office with jurisdiction limited to civil copyright cases capped at $30,000 in damages.

In December 2017, Representative Doug Collins introduced the Music Modernization Act of 2017, H.R. 4706. In January 2018, Senator Orrin Hatch introduced S. 2334. These bills would provide that online music services would pay for a broad blanket license that covers every song in a database entitled the "Mechanical Licensing Collective." The services would fund and publishers would administer the collective. In any lawsuit filed after January 1, 2018, against a complying service, plaintiffs could recover only royalties owed under the new system, not damages for infringement. In setting mechanical license royalty rates, the CRB would use the "willing buyer/willing seller" standard rather than the Section 801(b)(1) factors. Judges in the Southern District of New York, when setting rates for public performances of musical works, could consider rates for public performances of sound recordings. The bills would also change the current systems of assigning judges to oversee cases related to the ASCAP and BMI consent decrees. Currently one judge is permanently assigned to all ASCAP cases, and another is assigned to all BMI cases. The bills would require the cases to be assigned by lot to a judge according to the court's rules for the division of business among district judges.