Introduction

The 115th Congress continues its interest in U.S. research and development (R&D) and in evaluating support for federal R&D activities. The federal government has played an important role in supporting R&D efforts that have led to scientific breakthroughs and new technologies, from jet aircraft and the Internet to communications satellites, shale gas extraction, and defenses against disease. In recent years, widespread concerns about the federal debt, recent and projected federal budget deficits, and federal budget caps have driven difficult decisions about the prioritization of R&D, both in the context of the entire federal budget and among competing needs within the federal R&D portfolio. While these factors continue to exist, increases in the budget caps for FY2018 and FY2019 may reduce some of the pressure affecting these decisions.

The U.S. government supports a broad range of scientific and engineering R&D. Its purposes include specific concerns such as addressing national defense, health, safety, the environment, and energy security; advancing knowledge generally; developing the scientific and engineering workforce; and strengthening U.S. innovation and competitiveness in the global economy. Most of the R&D funded by the federal government is performed in support of the unique missions of individual funding agencies.

The federal R&D budget is an aggregation of the R&D activities of these agencies. There is no single, centralized source of R&D funds. Agency R&D budgets are developed internally as part of each agency's overall budget development process. R&D funding may be included either in accounts that are entirely devoted to R&D or in accounts that include funding for non-R&D activities. Agency budgets are subjected to review, revision, and approval by the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) and become part of the President's annual budget submission to Congress. The federal R&D budget is then calculated by aggregating the R&D activities of each federal agency.

Congress plays a central role in defining the nation's R&D priorities as it makes decisions about the level and allocation of R&D funding—overall, within agencies, and for specific programs. Some Members of Congress have expressed concerns about the level of federal spending (for R&D and for other purposes) in light of the federal deficit and debt. Other Members of Congress have expressed support for increased federal spending for R&D as an investment in the nation's future competitiveness. As Congress acts to complete the FY2019 appropriations process, it faces two overarching issues: the amount of the federal budget to be spent on federal R&D and the prioritization and allocation of the available funding.

This report begins with a discussion of the overall level of President Trump's FY2019 R&D request, followed by analyses of the R&D funding request from a variety of perspectives and for selected multiagency R&D initiatives. The remainder of the report then provides discussion and analysis of the R&D budget requests of selected federal departments and agencies that, collectively, account for approximately 99% of total federal R&D funding.

Selected terms associated with federal R&D funding are defined in the text box on the next page. Appendix A provides a list of acronyms and abbreviations.

|

Definitions Associated with Federal Research and Development Funding Two key sources of definitions associated with federal research and development funding are the White House Office of Management and Budget and the National Science Foundation. Office of Management and Budget. The Office of Management and Budget provides the following definitions of R&D-related terms in OMB Circular No. A-11, "Preparation, Submission, and Execution of the Budget" (July 2017).1 This document provides guidance to agencies in the preparation of the President's annual budget and instructions on budget execution. As reflected in the July 2017 update, OMB has adopted a refinement to the categories of R&D, replacing "development" with "experimental development," which more narrowly defines the set of activities to be included, resulting in lower reported R&D by some agencies, including the Department of Defense and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. This definition is used in the President's FY2019 budget. Conduct of R&D. Research and experimental development (R&D) activities are defined as creative and systematic work undertaken in order to increase the stock of knowledge—including knowledge of people, culture, and society—and to devise new applications using available knowledge. Basic Research. Basic research is defined as experimental or theoretical work undertaken primarily to acquire new knowledge of the underlying foundations of phenomena and observable facts. Basic research may include activities with broad or general applications in mind, but should exclude research directed towards a specific application or requirement. Applied Research. Applied research is defined as original investigation undertaken in order to acquire new knowledge. Applied research is, however, directed primarily towards a specific practical aim or objective. Experimental Development. Experimental development is defined as creative and systematic work, drawing on knowledge gained from research and practical experience, which is directed at producing new products or processes or improving existing products or processes. Like research, experimental development will result in gaining additional knowledge. R&D Equipment. R&D equipment includes amounts for major equipment for research and development. Includes acquisition, design, or production of major movable equipment, such as mass spectrometers, research vessels, DNA sequencers, and other major movable instruments for use in R&D activities. Includes programs of $1 million or more that are devoted to the purchase or construction of major R&D equipment R&D Facilities. R&D facilities includes amounts for the construction of facilities that are necessary for the execution of an R&D program. This may include land, major fixed equipment, and supporting infrastructure such as a sewer line or housing at a remote location. National Science Board/National Science Foundation. The National Science Board/National Science Foundation provides the following definitions of R&D-related terms in its Science and Engineering Indicators: 2018 report.2 Research and Development (R&D): Research and experimental development comprise creative and systematic work undertaken to increase the stock of knowledge—including knowledge of humankind, culture, and society—and its use to devise new applications of available knowledge. Basic Research: Experimental or theoretical work undertaken primarily to acquire new knowledge of the underlying foundations of phenomena and observable facts, without any particular application or use in view. Applied Research: Original investigation undertaken to acquire new knowledge; directed primarily, however, toward a specific, practical aim or objective. Experimental Development: Systematic work, drawing on knowledge gained from research and practical experience and producing additional knowledge, which is directed to producing new products or processes or to improving existing products or processes. |

The President's FY2019 Budget Request

On February 12, 2018, President Trump released his proposed FY2019 budget. In addition, on the same day, OMB issued an addendum that includes a request for an additional $12.9 billion in nondiscretionary R&D funding.3 According to OMB, the request for these additional funds was made possible by changes to spending caps in the Budget Control Act (BCA; P.L. 112-25) that were enacted on February 9, 2018, in the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 (P.L. 115-123).

In FY2018, the Trump Administration began using a new definition for development in its R&D calculations ("experimental development"). The new definition excludes some development activities, primarily at the Department of Defense (DOD) and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), that had been characterized as development in previous budgets. The new definition (experimental development) is used throughout this report for FY2017 and FY2019, except in the section "Department of Defense." According to OMB, the funds no longer included in the definition of development are, nevertheless, "requested in the FY 2019 budget request and support the development efforts to upgrade systems that have been fielded or have received approval for full rate production and anticipate production funding in the current or subsequent fiscal year."4 (See box below entitled "Caveats with Respect to Analysis of the FY2019 Budget Request" for additional information.)

Subsequent to the release of the President's budget, Congress enacted the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2018 (P.L. 115-141), appropriating full-year funding for FY2018, rendering the CR levels identified in the budget no longer relevant. Therefore, this report compares the President's request for FY2019 to the FY2017 level.

Under the new definition of R&D, and including the $12.9 billion proposed in the addendum, President Trump is proposing approximately $131.0 billion for R&D for FY2019, an increase of $5.7 billion above the FY2017 level (4.5%). Adjusted for inflation, the President's FY2019 R&D request represents a constant-dollar increase of 0.4% from the FY2017 actual level.5

The President's R&D request includes continued funding for existing single-agency and multiagency programs and activities, as well as new initiatives. This report provides government-wide, multiagency, and individual agency analyses of the President's FY2019 request as it relates to R&D and related activities. Additional information and analysis will be included as the House and Senate act on the President's budget request through appropriations bills.

|

Caveats for Analysis of the FY2019 Budget Request Several factors complicate the analysis of changes in R&D funding for FY2019, both in aggregate and for selected agencies. For example:

In addition, inconsistency among agencies in the reporting of R&D and the inclusion of R&D activities in accounts with non-R&D activities may result in different figures being reported by OMB and the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP), including those shown in Table 1, and those in agency budget analyses that appear later in this report. |

Federal R&D Funding Perspectives

Federal R&D funding can be analyzed from a variety of perspectives that provide different insights. The following sections examine the data by agency, by the character of the work supported, and by a combination of these two perspectives.

Federal R&D by Agency

Congress makes decisions about R&D funding through the authorization and appropriations processes primarily from the perspective of individual agencies and programs. Table 1 provides data on R&D funding by agency for FY2017 (actual) and FY2019 (request).6 Funding data for FY2018 were not included in the Trump Administration's FY2019 budget because the FY2018 budget had not been completed at the time the FY2019 budget request was released.

Under President Trump's FY2019 budget request, eight federal agencies would receive more than 96% of total federal R&D funding: the Department of Defense, 48.4%; Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), primarily the National Institutes of Health (NIH), 20.9%; Department of Energy (DOE), 10.7%; National Aeronautics and Space Administration, 9.0%; National Science Foundation (NSF), 3.5%; Department of Agriculture (USDA), 1.6%; Department of Commerce (DOC), 1.2%; and Veterans Affairs (VA), 1.1%. This report provides an analysis of the R&D budget requests for these agencies, as well as for the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), Department of the Interior (DOI), Department of Transportation (DOT), and Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

Excluding the $12.9 billion in R&D funding requested in the addendum, nearly every federal agency would see its R&D funding decrease under the President's FY2019 request compared to their FY2017 levels. The only agencies with increased R&D funding in FY2019 would be DOD (up $7.959 billion, 16.2%), the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute,7 (up $159 million, 34.3%), and the Smithsonian Institution (up $20 million, 8.0%).

The largest declines (as measured in dollars) would occur in the budgets of HHS (down $9.480 billion, 27.7%), DOE (down $2.211 billion, 14.8%), NSF (down $1.761 billion, 29.7%), USDA (down $671 million, 26.0%), and the DOC (down $433 million, 24.1%).

Table 1. Federal Research and Development Funding by Agency, FY2017 and FY2019

(budget authority, dollar amounts in millions)

|

Change, |

||||

|

Department/Agency |

FY2017 |

FY2019 |

Dollar |

Percent, Total |

|

Department of Defense |

49,197 |

57,156 |

7,959 |

16.2% |

|

Department of Health and Human Services |

34,222 |

24,742 |

-9,480 |

-27.7% |

|

Department of Energy |

14,896 |

12,685 |

-2,211 |

-14.8% |

|

NASA |

10,704 |

10,651 |

-53 |

-0.5% |

|

National Science Foundation |

5,938 |

4,177 |

-1,761 |

-29.7% |

|

Department of Agriculture |

2,585 |

1,914 |

-671 |

-26.0% |

|

Department of Commerce |

1,794 |

1,361 |

-433 |

-24.1% |

|

Department of Veterans Affairs |

1,346 |

1,345 |

-1 |

-0.1% |

|

Department of Transportation |

904 |

826 |

-78 |

-8.6% |

|

Department of the Interior |

953 |

759 |

-194 |

-20.4% |

|

Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institutea |

463 |

622 |

159 |

34.3% |

|

Department of Homeland Security |

724 |

548 |

-176 |

-24.3% |

|

Smithsonian Institution |

251 |

271 |

20 |

8.0% |

|

Environmental Protection Agency |

497 |

269 |

-228 |

-45.9% |

|

Department of Education |

254 |

240 |

-14 |

-5.5% |

|

Other |

561 |

490 |

-71 |

-12.7% |

|

Total, Base Budget |

$125,289 |

$118,056 |

-$7,233 |

-5.8% |

|

Addendum to the FY2019 Request (estimated) |

~12,900 |

~12,900 |

n/a |

|

|

Total, with Addendum |

$125,289 |

~$131,000 |

~$5,700 |

~4.5% |

Source: CRS analysis of data from Executive Office of the President (EOP), Office of Management and Budget, Analytical Perspectives, Budget of the United States Government, Fiscal Year 2019, February 12, 2018, pp. 238-239, https://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/budget/Analytical_Perspectives; Addendum to the President's FY2019 Budget to Account for the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018, https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/Addendum-to-the-FY-2019-Budget.pdf; and email communication between OMB and CRS, February 23, 2018.

Notes: Components may not sum to totals due to rounding. FY2017 and FY2019 amounts exclude non-experimental development funding. n/a = not applicable.

a. The Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute is funded through the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Trust Fund, which was established by Congress under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (P.L. 111-148). For more information, see https://www.pcori.org/.

Federal R&D by Character of Work, Facilities, and Equipment

Federal R&D funding can also be examined by the character of work it supports—basic research, applied research, or development—and by funding provided for construction of R&D facilities and acquisition of major R&D equipment. (See Table 2.) President Trump's FY2019 request includes $27.341 billion for basic research, down $6.986 billion (20.4%) from FY2017; $31.648 billion for applied research, down $6.500 billion (17.0%); $56.696 billion for development, up $6.333 billion (12.6%); and $2.371 billion for facilities and equipment, down $80 million (3.3%).

Table 2. Federal R&D Funding by Character of Work and Facilities and Equipment, FY2017 and FY2019

(budget authority, dollar amounts in millions)

|

Change, FY2017-FY2019 |

||||

|

Character of Work, Facilities, and Equipment |

FY2017 |

FY2019 Request |

Dollar |

Percent, Total |

|

Basic research |

34,327 |

27,341 |

-6,986 |

-20.4% |

|

Applied research |

38,148 |

31,648 |

-6,500 |

-17.0% |

|

Development |

50,363 |

56,696 |

6,333 |

12.6% |

|

Facilities and Equipment |

2,451 |

2,371 |

-80 |

-3.3% |

|

Total |

125,289 |

118,056 |

-7,233 |

-5.8% |

Source: CRS analysis of data from Executive Office of the President (EOP), Office of Management and Budget, Analytical Perspectives, Budget of the United States Government, Fiscal Year 2019, February 12, 2018, pp. 238-240, https://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/budget/Analytical_Perspectives.

Notes: Components may not sum to totals due to rounding. Does not include estimated $12.9 billion in R&D funding included in the Addendum to the President's FY2019 Budget to Account for the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018.

Federal Role in U.S. R&D by Character of Work

A primary policy justification for public investments in basic research and for incentives (e.g., tax credits) for the private sector to conduct research is the view, widely held by economists, that the private sector will, left on its own, underinvest in basic research from a societal perspective. The usual argument for this view is that the social returns (i.e., the benefits to society at large) exceed the private returns (i.e., the benefits accruing to the private investor, such as increased revenues or higher stock value). Other factors that may inhibit corporate investment in basic research include long time horizons for achieving commercial applications (diminishing the potential returns due to the time value of money), high levels of technical risk/uncertainty, shareholder demands for shorter-term returns, and asymmetric and imperfect information.

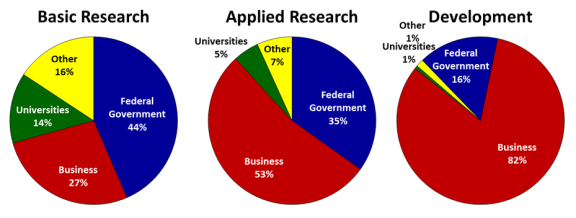

The federal government is the nation's largest supporter of basic research, funding 44% of U.S. basic research in 2016. Business funded 27% of U.S. basic research in 2016, with state governments, universities, and other nonprofit organizations funding the remaining 29%. For U.S. applied research, business is the primary funder, accounting for an estimated 53% in 2016, while the federal government accounted for an estimated 35%. State governments, universities, and other nonprofit organizations funded the remaining 12%. Business also provides the vast majority of U.S. funding for development. Business accounted for 82% of development funding in 2016, while the federal government provided 16%. State governments, universities, and other nonprofit organizations funded the remaining 2% (see Figure 1).8

Federal R&D by Agency and Character of Work Combined

Federal R&D funding can also be viewed from the combined perspective of each agency's contribution to basic research, applied research, development, and facilities and equipment. (Table 3 lists the three agencies with the most funding for each character of work classification.) The overall federal R&D budget reflects a wide range of national priorities, including supporting advances in spaceflight, developing new and affordable sources of energy, and understanding and deterring terrorist groups. These priorities and the mission of each individual agency contribute to the composition of that agency's R&D spending (i.e., the allocation among basic research, applied research, development, and facilities and equipment). In the President's FY2019 budget request, the Department of Health and Human Services, primarily NIH, would account for nearly half (44.3%) of all federal funding for basic research. HHS would also be the largest federal funder of applied research, accounting for about 39.0% of all federally funded applied research in the President's FY2019 budget request. DOD would be the primary federal funder of development, accounting for 87.4% of total federal development funding in the President's FY2019 budget request.9

Table 3. Selected R&D Funding Agencies by Character of Work, Facilities, and Equipment, FY2017 and FY2019

(budget authority, dollar amounts in millions)

|

Character of Work/Agency |

FY2017 |

FY2019 Request |

Change, FY2017-FY2019 |

|

|

Dollars |

Percent |

|||

|

Basic Research |

||||

|

Dept. of Health and Human Services |

$16,701 |

$12,114 |

-$4,587 |

-27.5% |

|

NASA |

3,607 |

4,150 |

+543 |

+15.1% |

|

National Science Foundation |

4,739 |

3,402 |

-1,337 |

-28.2% |

|

Applied Research |

||||

|

Dept. of Health and Human Services |

17,356 |

12,348 |

-5,008 |

-28.9% |

|

Dept. of Energy |

6,491 |

5,885 |

-606 |

-9.3% |

|

Dept. of Defense |

5,276 |

5,239 |

-37 |

-0.7% |

|

Development |

||||

|

Dept. of Defense |

41,545 |

49,579 |

+8,034 |

+19.3% |

|

NASA |

4,569 |

3,734 |

-835 |

-18.3% |

|

Dept. of Energy |

2,488 |

1865 |

-623 |

-25.0% |

|

Facilities and Equipment |

||||

|

Dept. of Energy |

1,115 |

1,537 |

+422 |

+37.8% |

|

Dept. of Health and Human Services |

138 |

245 |

+107 |

+77.5% |

|

Dept. of Commerce |

278 |

240 |

-38 |

-13.7% |

Source: CRS analysis of data from Executive Office of the President (EOP), Office of Management and Budget, Analytical Perspectives, Budget of the United States Government, Fiscal Year 2019, February 12, 2018, pp. 238-240, https://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/budget/Analytical_Perspectives.

Notes: The top three funding agencies in each category, based on the FY2019 request, are listed. Components may not sum to totals due to rounding. Does not include estimated $12.9 billion in R&D funding included in the Addendum to the President's FY2019 Budget to Account for the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018.

Multiagency R&D Initiatives

For many years, presidential budgets have reported on multiagency R&D initiatives and have often provided details of agency funding for these initiatives. Some of these efforts have a statutory basis—for example, the Networking and Information Technology Research and Development (NITRD) program, the National Nanotechnology Initiative (NNI), and the U.S. Global Change Research Program (USGCRP). These programs generally produce annual budget supplements identifying objectives, activities, funding levels, and other information, usually published shortly after the presidential budget release. Other multiagency R&D initiatives have operated at the discretion of the President without such a basis and may be eliminated at the discretion of the President. President Trump's FY2019 budget is largely silent on funding levels for these efforts and whether any or all of the nonstatutory initiatives will continue. Some activities related to these initiatives are discussed in agency budget justifications and may be addressed in the agency analyses later in this report. This section provides available multiagency information on these initiatives and will be updated as additional information becomes available.

Networking and Information Technology Research and Development Program (NITRD)10

Established by the High-Performance Computing Act of 1991 (P.L. 102-194), the Networking and Information Technology Research and Development program is the primary mechanism by which the federal government coordinates its unclassified networking and information technology R&D investments in areas such as supercomputing, high-speed networking, cybersecurity, software engineering, and information management. In FY2018, 21 agencies are NITRD members; non-member agencies also participate in NITRD activities. NITRD efforts are coordinated by the National Science and Technology Council (NSTC)11 Subcommittee on Networking and Information Technology Research and Development. Additional NITRD information can be obtained at https://www.nitrd.gov. The President's FY2019 budget request for the NITRD Program has not yet been released. The President's FY2018 budget request for the NITRD Program was $4.459 billion, a decrease of $0.33 billion compared to the $4.789 billion (enacted) in FY2017. The overall decrease was due to decreases of $234.7 million at NIH, $121.3 million at NSF, and smaller increases and decreases at other agencies. FY2018 appropriated amounts are not yet available.

Table 4. Networking and Information Technology Research and Development Program Funding, FY2017-FY2019

(budget authority, in millions of current dollars)

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

|

|

|

|

Source: Subcommittee on Networking and Information Technology Research and Development, Committee on Technology, National Science and Technology Council, The White House, Supplement to the President's Budget for Fiscal Year 2018, The Networking and Information Technology Research and Development Program, October 2017.

Notes: n/a = not available.

U.S. Global Change Research Program (USGCRP)12

The U.S. Global Change Research Program coordinates and integrates federal research and applications to understand, assess, predict, and respond to human-induced and natural processes of global change. The program seeks to advance global climate change science and to "build a knowledge base that informs human responses to climate and global change through coordinated and integrated Federal programs of research, education, communication, and decision support."13 In FY2018, 13 departments and agencies participated in the USGCRP. USGCRP efforts are coordinated by the NSTC Subcommittee on Global Change Research. Additional USGCRP information can be obtained at http://www.globalchange.gov. The Global Change Research Act of 1990 (P.L. 101-606) requires annual reporting to Congress on federal budget and spending by agency on global change research.14 In almost each of the past 17 years, language in appropriations laws has required the President to submit a comprehensive report to the appropriations committees "describing in detail all Federal agency funding, domestic and international, for climate change programs, projects, and activities … including an accounting of funding by agency…."15 The most recent report was submitted in December 2016 for FY2017. This section will be updated when the USGCRP updates its budget information.

Table 5. U.S. Global Change Research Program Funding, FY2017-FY2019

(budget authority, in millions of current dollars)

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

Source: U.S. Global Change Research Program, website, https://www.globalchange.gov/about/budget.

Note: n/a = not available.

National Nanotechnology Initiative (NNI)16

Launched in FY2001, the National Nanotechnology Initiative is a multiagency R&D initiative to advance understanding and control of matter at the nanoscale, where the physical, chemical, and biological properties of materials differ in fundamental and useful ways from the properties of individual atoms or bulk matter.17 In 2003, Congress enacted the 21st Century Nanotechnology Research and Development Act (P.L. 108-153), providing a legislative foundation for some of the activities of the NNI. In FY2018, the NNI included 16 federal departments and independent agencies and commissions with budgets dedicated to nanotechnology R&D, as well as other federal departments and independent agencies and commissions with responsibilities for health, safety, and environmental regulation; trade; education; training; intellectual property; international relations; and other areas that might affect or be affected by nanotechnology. NNI efforts are coordinated by the NSTC Subcommittee on Nanoscale Science, Engineering, and Technology (NSET). In FY2017, NNI funding was an estimated $1.470 billion.18 FY2018 appropriated amounts are not yet available. The FY2019 request level for the NNI was not included in the FY2019 budget. Additional NNI information can be obtained at http://www.nano.gov. This section will be updated when the NSET subcommittee updates its published budget information.

Table 6. National Nanotechnology Initiative Funding, FY2017-FY2019

(budget authority, in millions of current dollars)

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

|

|

|

|

Source: Subcommittee on Nanoscale Science, Engineering, and Technology, Committee on Technology, National Science and Technology Council, The White House, Supplement to President Obama's Budget for Fiscal Year 2018, The National Nanotechnology Initiative: Research and Development Leading to a Revolution in Technology and Industry, November 2017.

Other Initiatives

Presidential initiatives without statutory foundations in operation at the end of the Obama Administration, but not explicitly addressed in President Trump's FY2018 or FY2019 budgets, include: the Advanced Manufacturing Partnership (AMP, including the National Robotics Initiative [NRI] and the National Network for Manufacturing Innovation [NNMI]), 19 the Cancer Moonshot, the BRAIN Initiative, the Precision Medicine Initiative (PMI), the Materials Genome Initiative, and an effort to doubling federal funding for clean energy R&D. Some of the activities of these initiatives are discussed in agency budget justifications and the agency analyses later in this report.

FY2019 Appropriations Status

The remainder of this report provides a more in-depth analysis of R&D in 12 federal departments and agencies that, in aggregate, receive nearly 99% of total federal R&D funding. Agencies are presented in order of the size of their FY2019 R&D budget requests, with the largest presented first. Agency analyses compare FY2019 request levels to FY2017 actual levels.

Annual appropriations for these agencies are provided through 9 of the 12 regular appropriations bills. For each agency covered in this report, Table 7 shows the corresponding regular appropriations bill that provides primary funding for the agency, including its R&D activities.

Because of the way that agencies report budget data to Congress, it can be difficult to identify the portion that is R&D. Consequently, R&D data presented in the agency analyses in this report may differ from R&D data in the president's budget or otherwise provided by OMB.

Funding for R&D is often included in appropriations line items that also include non-R&D activities; therefore, in such cases, it may not be possible to identify precisely how much of the funding provided in appropriations laws is allocated to R&D specifically. In general, R&D funding levels are known only after departments and agencies allocate their appropriations to specific activities and report those figures.

This report will be updated as Congress takes actions to complete the FY2019 appropriations process.

In addition to this report, CRS produces individual reports on each of the appropriations bills. These reports can be accessed via the CRS website at http://www.crs.gov/iap/appropriations. Also, the status of each appropriations bill is available on the CRS web page, Status Table of Appropriations, available at http://www.crs.gov/AppropriationsStatusTable/Index.

|

Department/Agency |

Regular Appropriations Bill |

|

Department of Defense |

Department of Defense Appropriations Act |

|

Department of Health and Human Services |

(1) Departments of Labor, Health and Human Services, and Education, and Related Agencies Appropriations Act (2) Department of the Interior, Environment, and Related Agencies Appropriations Act |

|

Department of Energy |

Energy and Water Development and Related Agencies Appropriations Act |

|

National Aeronautics and Space Administration |

Commerce, Justice, Science, and Related Agencies Appropriations Act |

|

National Science Foundation |

Commerce, Justice, Science, and Related Agencies Appropriations Act |

|

Department of Agriculture |

Agriculture, Rural Development, Food and Drug Administration, and Related Agencies Appropriations Act |

|

Department of Commerce |

Commerce, Justice, Science, and Related Agencies Appropriations Act |

|

Department of Veterans Affairs |

Military Construction and Veterans Affairs, and Related Agencies Appropriations Act |

|

Department of the Interior |

Department of the Interior, Environment, and Related Agencies Appropriations Act |

|

Department of Transportation |

Transportation, Housing and Urban Development, and Related Agencies Appropriations Act |

|

Department of Homeland Security |

Department of Homeland Security Appropriations Act |

|

Environmental Protection Agency |

Department of the Interior, Environment, and Related Agencies Appropriations Act |

Source: CRS Report R40858, Locate an Agency or Program Within Appropriations Bills, by [author name scrubbed].

Department of Defense20

The mission of the Department of Defense is "to provide the military forces needed to deter war and to protect the security of our country."21 Congress supports research and development activities at DOD primarily through the department's Research, Development, Test, and Evaluation (RDT&E) funding. These funds support the development of the nation's future military hardware and software and the science and technology base upon which those products rely.

Nearly all of what DOD spends on RDT&E is appropriated in Title IV of the annual defense appropriations bill. (See Table 8.) However, RDT&E funds are also appropriated in other parts of the bill. For example, RDT&E funds are appropriated as part of the Defense Health Program, the Chemical Agents and Munitions Destruction Program, and the National Defense Sealift Fund. The Defense Health Program (DHP) supports the delivery of health care to DOD personnel and their families. DHP funds (including the RDT&E funds) are requested through the Defense-wide Operations and Maintenance appropriations request. The program's RDT&E funds support congressionally directed research on breast, prostate, and ovarian cancer; traumatic brain injuries; orthotics and prosthetics; and other medical conditions. Congress appropriates funds for this program in Title VI (Other Department of Defense Programs) of the defense appropriations bill. The Chemical Agents and Munitions Destruction Program supports activities to destroy the U.S. inventory of lethal chemical agents and munitions to avoid future risks and costs associated with storage. Funds for this program are requested through the Defense-wide Procurement appropriations request. Congress appropriates funds for this program also in Title VI. The National Defense Sealift Fund supports the procurement, operation and maintenance, and research and development associated with the nation's naval reserve fleet and supports a U.S. flagged merchant fleet that can serve in time of need. The RDT&E funding for this effort is requested in the Navy's Procurement request and appropriated in Title V (Revolving and Management Funds) of the appropriation bill.

RDT&E funds also have been requested and appropriated as part of DOD's separate funding to support efforts in what the George W. Bush Administration termed the Global War on Terror (GWOT), and what the Obama and Trump Administration have referred to as Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO). In appropriations bills, the term Overseas Contingency Operations/Global War on Terror (OCO/GWOT) has been used; President Trump's FY2019 budget uses the term Overseas Contingency Operations. Typically, the RDT&E funds appropriated for OCO/GWOT activities go to specified Program Elements (PEs) in Title IV.

In addition, OCO/GWOT-related requests/appropriations have included money for a number of transfer funds. In the past, these have included the Iraqi Freedom Fund (IFF), the Iraqi Security Forces Fund, the Afghanistan Security Forces Fund, and the Pakistan Counterinsurgency Capability Fund. Congress typically has made a single appropriation into each such fund and authorized the Secretary to make transfers to other accounts, including RDT&E, at his discretion. These transfers are eventually reflected in Title IV prior-year funding figures.

Because final FY2018 funding was not available at the time the FY2019 budget was prepared, requested funding is compared to the FY2017 actual funding.

For FY2019, the Trump Administration is requesting $92.365 billion for DOD's Title IV RDT&E PEs (base plus OCO/GWOT), $17.547 billion (23.5%) above the enacted FY2017 level. In addition, the request includes $710.6 million in RDT&E through the Defense Health Program (DHP; down $1.391 billion, 66.2% from FY2017), $886.7 million in RDT&E through the Chemical Agents and Munitions Destruction program (up $371.1 million, 72.0% from FY2017), and $1.6 million for the Inspector General for RDT&E-related activities, down $3.0 million from FY2017 (65.3%). The FY2019 budget included no RDT&E funding via the National Defense Sealift Fund, which received $7.2 million in FY2017.

The military departments each request and receive their own RDT&E funding. So do various DOD agencies (e.g., the Missile Defense Agency and the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency), through the Defense-wide account. The Director, Operational Test and Evaluation, receives a separate appropriation. RDT&E funding can also be characterized by budget activity (i.e., the type of RDT&E supported). Those budget activities designated as 6.1, 6.2, and 6.3 (basic research, applied research, and advanced technology development) constitute what is called DOD's Science and Technology (S&T) program. Budget activities 6.4 and 6.5 focus on the development of specific weapon systems or components for which an operational need has been determined and an acquisition program established. Budget activity 6.6 provides management support, including support for test and evaluation facilities. Budget activity 6.7 supports the development of system improvements in existing operational systems.22

Many congressional policymakers are particularly interested in DOD S&T program funding since these funds support the development of new technologies and the underlying science. Some in the defense community see ensuring adequate support for S&T activities as imperative to maintaining U.S. military superiority into the future. The knowledge generated at this stage of development may also contribute to advances in commercial technologies. The FY2019 request for Title IV S&T funding (base plus OCO/GWOT) is $13.700 billion, $305.2 million (2.3%) above the FY2017 level.

Within the S&T program, basic research (6.1) receives special attention, particularly by the nation's universities. DOD is not a large supporter of basic research when compared to NIH or NSF. However, over half of DOD's basic research budget is spent at universities, and it is among the largest sources of funds for university research in some areas of science and technology, such as electrical engineering and materials science.23 The Trump Administration is requesting $2.269 billion for DOD basic research for FY2019. This is $71.1 million (3.2%) above than the FY2017 level.

|

|

FY2017 |

FY2019 |

FY2019 |

FY2019 |

FY2019 |

||

|

Base + OCO |

Base |

OCO |

Total |

||||

|

Army |

$ 8,852.5 |

$ 10,159.4 |

$ 325.1 |

$ 10,484.5 |

|||

|

Navy |

17,852.0 |

18,451.1 |

198.4 |

18,649.5 |

|||

|

Air Force |

28,381.7 |

39,892.1 |

600.5 |

40,492.6 |

|||

|

Defense-wide |

19,542.6 |

21,892.5 |

624.6 |

22,517.1 |

|||

|

Director, Operational Test & Evaluation |

188.7 |

221.0 |

0 |

221.0 |

|||

|

Total Title IV—By Account |

$74,817.4 |

$90,616.1 |

$1,748.6 |

$92,364.7 |

|||

|

Budget Activity |

|

||||||

|

6.1 Basic Research |

2,198.1 |

2,269.2 |

0 |

2,269.2 |

|||

|

6.2 Applied Research |

5,125.0 |

5,100.4 |

0 |

5,100.4 |

|||

|

6.3 Advanced Technology Development |

6,072.1 |

6,292.1 |

38.6 |

6,330.8 |

|||

|

6.4 Advanced Component Development and Prototypes |

15,593.0 |

20,862.8 |

318.0 |

21,180.7 |

|||

|

6.5 Systems Dev. and Demonstration |

13,034.6 |

15,338.5 |

238.0 |

15,576.5 |

|||

|

6.6 Management Supporta |

5,845.0 |

6,520.6 |

0 |

6,520.6 |

|||

|

6.7 Operational Systems Developmentb |

26,949.6 |

34,232.5 |

1,154.0 |

35,386.5 |

|||

|

Total Title IV—by Budget Activity |

$74,817.4 |

$90,616.1 |

$1,748.6 |

$92,364.7 |

|||

|

Title V—Revolving and Management Funds |

|

||||||

|

National Defense Sealift Fund |

7.2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|||

|

Title VI—Other Defense Programs |

|

||||||

|

Defense Health Program |

2,101.6 |

710.6 |

0 |

710.6 |

|||

|

Chemical Agents and Munitions Destruction |

515.6 |

886.7 |

0 |

886.7 |

|||

|

Inspector General |

4.6 |

1.6 |

0 |

1.6 |

|||

|

Grand Total |

$77,446.5 |

$92,215.1 |

$1,748.6 |

$93,963.6 |

|||

Source: CRS analysis of Department of Defense Budget, Fiscal Year 2019, RDT&E Programs (R‑1), February 2018.

Notes: Figures for the columns headed "FY2019 House," "FY2019 Senate," and "FY2019 Enacted" will be added, if available, as each action is completed. Totals may differ from the sum of the components due to rounding.

a. Includes funding for Director of Test and Evaluation.

b. Includes funding for Classified Programs.

c. According to DOD, "Total Obligation Authority (TOA) is the sum of: 1) all budget authority (BA) granted (or requested) from the Congress in a given year, 2) amounts authorized to be credited to a specific fund, 3) BA transferred from another appropriation, and 4) Unobligated balances of BA from previous years which remain available for obligation. In practice, this term is used primarily in discussing the DoD budget, and most often refers to TOA as the 'direct program,' which equates to only (1) and (2) above." DOD defines "budget authority" as "the authority becoming available during the year to enter into obligations that result in immediate or future outlays of Government funds." See DoD 7000.14-R, "Department of Defense Financial Management Regulation," http://comptroller.defense.gov/fmr.aspx.

Department of Health and Human Services

The mission of the Department of Health and Human Services is "to enhance and protect the health and well-being of all Americans ... by providing for effective health and human services and fostering advances in medicine, public health, and social services."24 This section focuses on HHS research and development funded through the National Institutes of Health, an HHS agency that accounts for more than 95% of total HHS R&D funding.25 Other HHS agencies that provide funding for R&D include the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), and the Administration for Children and Families (ACF).26

National Institutes of Health27

NIH is the primary agency of the federal government charged with performing and supporting biomedical and behavioral research. It also has major roles in training biomedical researchers and disseminating health information. The NIH mission is "to seek fundamental knowledge about the nature and behavior of living systems and the application of that knowledge to enhance health, lengthen life, and reduce illness and disability."28 The agency's organization consists of the NIH Office of the Director (OD) and 27 institutes and centers (ICs).

The OD sets overall policy for NIH and coordinates the programs and activities of all NIH components, particularly in areas of research that involve multiple institutes. The ICs focus on particular diseases, areas of human health and development, or aspects of research support. Each IC plans and manages its own research programs in coordination with OD. As shown in Table 9, separate appropriations are provided to 24 of the 27 ICs, to OD, and to an intramural Buildings and Facilities account. The other three centers, which perform centralized support services, are funded through assessments on the IC appropriations.

NIH supports and conducts a wide range of basic and clinical research, research training, and health information dissemination across all fields of biomedical and behavioral sciences. About 10% of the NIH budget supports intramural research projects conducted by the nearly 6,000 NIH scientists, most of whom are located on the NIH campus in Bethesda, MD. More than 80% of NIH's budget goes out to the extramural research community in the form of grants, contracts, and other awards. This funding supports research performed by more than 300,000 nonfederal scientists and technical personnel who work at more than 2,500 universities, hospitals, medical schools, and other research institutions.29

Funding for NIH comes primarily from the annual Labor, HHS, and Education (LHHS) appropriations act, with an additional amount for Superfund-related activities from the Interior/Environment appropriations act. Those two appropriations acts provide NIH's discretionary budget authority. In addition, NIH has received mandatory funding of $150 million annually that is provided in the Public Health Service (PHS) Act for a special program on type 1 diabetes research and funding from a PHS Act transfer. The total funding available for NIH activities, taking account of add-ons and transfers, is known as the NIH program level.

Because final FY2018 funding was not available at the time the FY2019 budget was prepared, requested funding is compared to the FY2017 actual funding.

President Trump's FY2019 budget requests an NIH program level total of $34.767 billion, an increase of $538 million (1.6%) from the FY2017 enacted level. The increase in FY2019 would be concentrated in the OD and three ICs: the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, the National Institute of Mental Health, and the National Institute on Drug Abuse. Much of this funding increase is intended to address the opioid epidemic (see Table 9).30 Buildings and Facilities would also receive a 55% increase in funding for FY2019 compared to FY2017. Under President Trump's FY2019 budget request, all other ICs would receive a decrease compared to FY2017.

The FY2019 NIH budget request proposes the consolidation of other existing HHS research programs with NIH, establishing three new NIH Institutes.31 The creation of three new NIH Institutes would require an amendment to the Public Health Service Act, considering that a provision in the NIH Reform Act of 2006 (P.L. 109-482; PHS Act §401[d]) states that the number of NIH ICs "may not exceed a total of 27."

As in the FY2018 proposal, the Trump budget again proposes the consolidation of the AHRQ with NIH, forming a new Institute called the National Institute for Research on Safety and Quality (NIRSQ). The FY2019 budget proposal includes $380 million in budget authority for NIRSQ "to coordinate and ensure a continued focus on research to improve health care quality and patient safety."32 Of this, $256 million would be used "to continue selected unique, systemically-important activities formerly funded by AHRQ that have demonstrated effectiveness in improving healthcare quality."33 NIRSQ would provide administrative support for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF). In the FY2019 budget proposal, NIRSQ would provide $7 million in administrative support to USPSTF—a reduction of $4 million (-36%) below AHRQ's FY2017 level.34 Additionally, the President's FY2019 budget proposal states that NIRSQ is projected to receive $124 million in mandatory resources from the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Trust Fund "to disseminate findings from comparative clinical effectiveness studies and train researchers on how to conduct high-quality studies in this area of research."35

Under the President's FY2019 budget proposal, the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), currently housed within the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, would be consolidated into the NIH. NIOSH targets "research needed to prevent the societal cost of work-related fatalities, injuries, and illnesses in the United States."36 The FY2019 budget includes $200 million for this line of research, a reduction of $134 million (-40%) compared with the $334 million enacted for FY2017.37 An additional $55 million in mandatory funding is also provided for the Energy Employees Occupational Illness Compensation Program Act. Through this program NIOSH conducts activities to assist claimants and "provides compensation and medical benefits to employees who worked at certain Department of Energy facilities."38 The Department of Labor manages claims filed under the act.

The National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research (NIDILRR), currently housed under the Administration for Community Living in HHS, would also be folded into NIH under the President's FY2019 budget. The mission of NIDILRR is "to generate new knowledge and promote its effective use to improve the abilities of people with disabilities to perform activities of their choice in the community, and to expand society's capacity to provide full opportunities and accommodations for its citizens with disabilities."39 Under this arrangement, NIDILRR activities are designed to complement existing NIH research addressing disabilities and aging. The President's budget would provide $95 million for NIDILRR for FY2019, a $9 million reduction (-9%) from the $104 million enacted for FY2017.40

The main funding mechanism NIH uses to support extramural research is research project grants (RPGs), which are competitive, peer-reviewed, and largely investigator-initiated. Historically, over 50% of the NIH budget is used to support RPGs, which include salaries for investigators and research staff. The President's FY2019 budget proposal includes two initiatives designed to "stretch available grant dollars" by placing limits on salaries for investigators.41 The FY2019 budget proposes to cap the percentage of an investigator's salary that can be paid with grant funds to 90%. It also proposes to cap investigator salaries at $152,000, a 19% reduction from the current $187,000 limit.

The FY2019 program level request for NIH includes $54 million for Superfund-related health research.42 The FY2019 Trump budget proposes shifting the $150 million in mandatory funding for research on type 1 diabetes authorized under the PHS Act §330B to discretionary funding within the budget of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK).43 The FY2019 program level request proposes $741 million in funding transferred to NIH by the PHS Program Evaluation Set-Aside, also called the evaluation tap. Discretionary funding programs at NIH and other HHS agencies that are authorized under the PHS Act are subject to an assessment under Section 241 of the PHS Act (42 U.S.C. §238j). This provision authorizes the Secretary to use a portion of eligible appropriations to study the effectiveness of federal health programs and to identify improvements. Although the PHS Act limits the tap to no more than 1% of eligible appropriations, in recent years, annual LHHS appropriations acts have specified a higher amount (2.5% in FY2017) and have also typically directed specific amounts of funding from the tap for transfer to a number of HHS programs. The assessment has the effect of redistributing appropriated funds for specific purposes among PHS and other HHS agencies. NIH, with the largest budget among the PHS agencies, has historically been the largest "donor" of program evaluation funds; until recently, it had been a relatively minor recipient.44 Provisions in recent LHHS appropriations acts have directed specific tap transfers to NIH, making NIH a net recipient of tap funds.

With the exception of the mandatory type 1 diabetes funding provided in previous years, Congress has not usually specified amounts for particular diseases or research areas. Generally specific amounts are appropriated to each IC; NIH and its scientific advisory panels allocate the funding to various research areas. This allows maximum flexibility for NIH to pursue scientific opportunities that are important to public health.45 Some bills may propose authorizations for designated research purposes, but funding generally has remained subject to the NIH peer review process as well as the overall discretionary appropriation to the agency. This pattern has changed in recent years, most notably in FY2016 with Alzheimer's disease research46 and in FY2017 with the NIH Innovation account established by the 21st Century Cures Act (P.L. 114-255, see text box below).

The FY2019 total NIH budget request includes $711 million in resources made available through the 21st Century Cures Act. This includes support for the Precision Medicine Initiative's All of Us Research Program established by the Cures Act in 2015. This research initiative includes a national resource of clinical, environmental, lifestyle, and genetic data from one million or more participants who will contribute health information over many years. National roll-out of this program begins in 2018 with the first stages of enrollment scheduled to begin in spring 2018.

The President's FY2019 budget identifies several research priorities for NIH in the coming year. The overview below outlines these priority themes in the budget request.

|

The 21st Century Cures Act and the NIH Innovation Account The 21st Century Cures Act (P.L. 114-255) created the NIH Innovation account and specified that funds in the account must be appropriated in order to be available for expenditure. The first round of funding was provided by Section 194 of the Further Continuing and Security Assistance Appropriations Act, 2017 (CR, P.L. 114-254). The CR appropriated $352 million in the NIH Innovation account for necessary expenses to carry out the four NIH Innovation Projects as described in Section 1001(b)(4) of the Cures Act. The FY2019 total NIH budget request includes $711 million made available through the 21st Century Cures Act. The Cures Act authorizes four projects in the following amounts: Precision Medicine Initiative (FY2017, $40 million; FY2018, $100 million; FY2019, $186 million), the BRAIN Initiative (FY2017, $10 million; FY2018, $86 million, FY2019, $115 million), cancer research (FY2017, $300 million; FY2018, $300 million; FY2019 $400 million), and regenerative medicine using adult stem cells (FY2017, $2 million; FY2018, $10 million; FY2019, $10 million). Amounts, once appropriated, are to be available until expended. The NIH Director may transfer these amounts from the NIH Innovation account to other NIH accounts but only for the purposes specified in the Cures Act. If the NIH Director determines that the funds for any of the four Innovation Projects are not necessary, the amounts may be transferred back to the NIH Innovation account. This transfer authority is in addition to other transfer authorities provided by law. For further information, see CRS Report R44720, The 21st Century Cures Act (Division A of P.L. 114-255), coordinated by [author name scrubbed], and CRS Report R44723, Overview of Further Continuing Appropriations for FY2017 (H.R. 2028), coordinated by [author name scrubbed]. |

1. Tackling Complex Challenges by Leveraging Partnerships. NIH partners with other government agencies and private entities to collaborate on research. The President's budget proposal states that "public-private partnerships can create efficiencies of scale and facilitate development of innovative technologies or treatments, thereby increasing the pace of biomedical research."47 For example, the Accelerating Medicines Partnership is a public-private partnership between NIH, FDA, and several biopharmaceutical companies and nonprofit organizations. With the goal of increasing the number of new diagnostics and therapies for patients, the Partnership aims to jointly identify promising biological targets for therapeutics.

Since 2014, the Partnership has been addressing Alzheimer's disease, type 2 diabetes, and two autoimmune disorders (rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus); a new Parkinson's disease initiative was also recently inaugurated. NIH will also enhance existing research efforts using a similar public-partnership model to address the opioid crisis. The goal of this endeavor is to develop new formulations of medications to treat opioid misuse and accelerate the development of non-addictive pain therapies. The FY2019 budget proposal would provide NIH $350 million from the new $10 billion investment requested for opioids, serious mental illness, and pain related research at NIH.48

2. Supporting Basic Research to Drive New Understanding of Health and Disease in Living Systems. NIH is the largest funder of basic biomedical research in the United States. As mentioned previously, each year more than half of the NIH budget goes toward basic research, which provides "a critical research foundation for both the public and private sectors to build upon."49 NIH funds a broad spectrum of basic science research. For example, addressing the opioid crisis requires understanding how pain is sensed and perceived, and how changes in neural circuits create a state of dependency. Basic research on neural pathways in the brain related to pain and substance use may provide an avenue for better treatments for pain, without the potential for addiction.

3. Investing in Translational and Clinical Research to Improve Health. NIH builds on the foundation of basic research by supporting translational and clinical research that seeks to convert this basic science knowledge into interventions. Translational research aims to "translate" findings from basic science into medical practice to produce meaningful health outcomes.50 Likewise, clinical research, which uses human subjects, helps professionals find new and better ways to understand, detect, control, and treat illness. NIH is investing in large population studies to learn more about the similarities and differences among individuals and facilitate integrated understanding of health and disease at all levels, from the molecular to the social. For example, as previously mentioned, NIH would continue to establish a group of 1 million or more volunteers through the Precision Medicine Initiative's All of Us Research Program. This research project involves the collection of health, genetic, environmental, and other data from participants for use in research studies designed to identify novel therapeutics and prevention strategies.

In addition to the above three priorities, the President's budget also identifies the following as goals for FY2019:

- Updating the infrastructure of NIH facilities. An independent review is currently being conducted of the capital needs of the 281 facilities located on NIH's main campus, including its research hospital, laboratories, and offices.

- Fostering a diverse and talented research workforce. The FY2019 budget proposal includes $100 million in dedicated funding to the OD for the Next Generation Research Initiative to "address longstanding challenges faced by researchers trying to embark upon and sustain independent research careers."51

- Advancing data science. The FY2019 budget would continue to support the Big Data to Knowledge (BD2K) initiative established in 2012. The FY2019 budget includes $30 million for NIH to build on the progress of the BD2K as this initiative enters its final stages.

- Encouraging innovation through prize competitions. The FY2019 budget proposal would allocate $50 million for prize competitions to improve health outcomes, particularly for research for which there is potential for significant return on investment.

|

Institutes/Centers |

FY2017 |

FY2019 |

FY2019 |

FY2019 |

FY2019 |

||

|

Cancer Institute (NCI) |

|

|

|||||

|

Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) |

|

|

|||||

|

Dental/Craniofacial Research (NIDCR) |

|

|

|||||

|

Diabetes/Digestive/Kidney (NIDDK)a |

|

|

|||||

|

Neurological Disorders/Stroke (NINDS) |

|

|

|||||

|

Allergy/Infectious Diseases (NIAID) |

|

|

|||||

|

General Medical Sciences (NIGMS)b |

|

|

|||||

|

Child Health/Human Development (NICHD) |

|

|

|||||

|

National Eye Institute (NEI) |

|

|

|||||

|

Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS)c |

|

|

|||||

|

National Institute on Aging (NIA) |

|

|

|||||

|

Arthritis/Musculoskeletal/Skin Diseases (NIAMS) |

|

|

|||||

|

Deafness/Communication Disorders (NIDCD) |

|

|

|||||

|

National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) |

|

|

|||||

|

National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) |

|

|

|||||

|

Alcohol Abuse/Alcoholism (NIAAA) |

|

|

|||||

|

Nursing Research (NINR) |

|

|

|||||

|

Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI) |

|

|

|||||

|

Biomedical Imaging/Bioengineering (NIBIB) |

|

|

|||||

|

Minority Health/Health Disparities (NIMHD) |

|

|

|||||

|

Complementary/Integrative Health (NCCIH) |

|

|

|||||

|

Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) |

|

|

|||||

|

Fogarty International Center (FIC) |

|

|

|||||

|

National Library of Medicine (NLM) |

|

|

|||||

|

Office of Director (OD) |

|

|

|||||

|

Buildings and Facilities (B&F) |

|

|

|||||

|

Natl Institute for Research on Safety & Quality (NIRSQ)d |

|

|

|||||

|

Natl Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH)e |

|

|

|||||

|

Natl Institute Disability/Independent Living/Rehabilitation Research (NIDILRR) |

|

|

|||||

|

Subtotal, NIH |

|

|

|||||

|

PHS Program Evaluation |

|

|

|||||

|

Superfund (Interior approp. to NIEHS)f |

|

|

|||||

|

Mandatory type 1 diabetes fundsg |

|

|

|||||

|

Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Trust Fund |

|

|

|||||

|

Energy Employees Occupational Illness Compensation |

|

|

|||||

|

NIH Program Level |

|

|

|||||

|

Additional opioids allocation |

|

|

|||||

|

Total, NIH Program Level |

|

|

Source: Department of Health and Human Services, Fiscal Year 2019 Budget in Brief, Washington, DC, February 2018, p. 40-41, https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/fy-2019-budget-in-brief.pdf.

Notes: Figures for the columns headed "FY2019 House," "FY2019 Senate," and "FY2019 Enacted" will be added, if available, as each action is completed. Totals may differ from the sum of the components due to rounding. Amounts in table may differ from actuals in many cases. By convention, budget tables such as Table 9 do not subtract the amount of transfers, such as the evaluation tap, from the agencies' appropriation.

a. Amounts for the FY2017 National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) do not include mandatory funding for type 1 diabetes research (see note g). Amounts for FY2019 NIDDK include funding for type 1 diabetes research. The President's FY2019 budget proposes to shift this from mandatory funding to discretionary funding. More information can be found in the addendum to the FY2019 President's Budget, Letter from Mick Mulvaney, Director, Office of Management and Budget, to Paul D. Ryan, Speaker of the House of Representatives, February 12, 2018, https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/Addendum-to-the-FY-2019-Budget.pdf.

b. Amounts for National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS) do not include funds from PHS Evaluation Set-Aside (§241 of the PHS Act) ($824 million for FY2017 and $741 million for FY2019).

c. Amounts for National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) do not include Interior Appropriation for Superfund research (see note f).

d. Amount for NIRSQ does not include the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Trust Fund (PCORTF).

e. Amount for NIOSH does not include the Energy Employees Occupational Illness Compensation funds.

f. This is a separate account in the Interior/Environment appropriations for National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) research activities related to Superfund.

g. Mandatory funds available to NIDDK for type 1 diabetes research under PHS Act §330B (provided by P.L. 114-10 for FY2017). These funds are specified at $150 million annually; however, in FY2017 $140 million was provided due to sequestration. In the FY2019 budget proposal these funds are included as discretionary funds within the NIDDK budget, rather than mandatory funds.

Department of Energy52

The Department of Energy (DOE) was established in 1977 by the Department of Energy Organization Act (P.L. 95-91), which combined energy-related programs from a variety of agencies with defense-related nuclear programs that dated back to the Manhattan Project. Today, DOE conducts basic scientific research in fields ranging from nuclear physics to the biological and environmental sciences; basic and applied R&D relating to energy production and use; and R&D on nuclear weapons, nuclear nonproliferation, and defense nuclear reactors. The department has a system of 17 national laboratories around the country, mostly operated by contractors, that together account for about 40% of all DOE expenditures.

Because final FY2018 funding was not available at the time the FY2019 budget was prepared, requested funding is compared to the FY2017 actual funding.

The Administration's FY2019 budget request for DOE includes about $11.720 billion for R&D and related activities, including programs in three broad categories: science, national security, and energy. This request is 10.8% less than the enacted FY2017 amount of $13.140 billion. (See Table 10 for details.)

The request for the DOE Office of Science is $5.391 billion, almost the same as the FY2017 appropriation of $5.392 billion. Within that total, however, some of the office's six major research programs would receive substantial increases or decreases. Funding for Advanced Scientific Computing Research would increase by $252 million (39.0%), largely to support the DOE-wide Exascale Computing Initiative. Funding for Biological and Environmental Research would decrease by $112 million (18.3%), with the reductions concentrated in the Earth and Environmental Systems Sciences subprogram (down $124 million, 40.5%), as the Biological Systems Science subprogram would receive an increase (up $12 million, 3.8%). Funding for Fusion Energy Sciences would decrease by $40 million (10.5%), despite an increase to $75 million (from $50 million in FY2017) for the U.S. contribution to construction of the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor (ITER), a fusion energy demonstration and research facility in France.

The request for DOE national security R&D is $4.268 billion, an increase of 13.5% from $3.760 billion in FY2017. The bulk of the increase would be in the Naval Reactors program (up $368 million, 25.9%). In the Weapons Activities account (up $153 million, 8.3%) requested increases for most programs would be partially offset by a decrease of $104 million (19.9%) for Inertial Confinement Fusion. Within Inertial Confinement Fusion, more than half of the proposed decrease would be in the Ignition subprogram (down $55 million, 71.2%), and support for the Laboratory for Laser Energetics ($68 million in FY2017, $45 million in the FY2019 request) would be phased out over three years.

The request for DOE energy R&D is $2.061 billion, a decrease of 48.3% from $3.988 billion in FY2017. Funding for energy efficiency and renewable energy R&D would decrease by 61.6%, with reductions in all major research areas and a shift in emphasis toward early-stage R&D rather than later-stage development and deployment. Funding for fossil energy R&D would decrease by 24.8%, with reductions focused particularly on coal carbon capture and storage ($40 million, down from $196 million in FY2017) and natural gas technologies ($6 million, down from $43 million in FY2017). Funding for nuclear energy would decrease by 25.5%, with no funding requested for small modular reactor licensing technical support ($95 million in FY2017), the Integrated University Program ($5 million in FY2017), or the Supercritical Transformational Electric Power (STEP) R&D initiative ($5 million in FY2017), and $60 million for fuel cycle R&D (down from $208 million in FY2017). The Advanced Research Projects Agency–Energy (ARPA-E), which is intended to advance high-impact energy technologies that have too much technical and financial uncertainty to attract near-term private-sector investment, would be terminated.

Table 10. Department of Energy R&D and Related Activities

(budget authority, in millions of dollars)

|

FY2017 |

FY2019 Request |

FY2019 House |

FY2019 Senate |

FY2019 Enacted |

|||||||

|

Science |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

Basic Energy Sciences |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

High Energy Physics |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

Biological and Environmental Research |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

Nuclear Physics |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

Advanced Scientific Computing Research |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

Fusion Energy Sciences |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

Other |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

National Security |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

Weapons Activities RDT&E |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

Naval Reactors |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

Defense Nuclear Nonproliferation R&D |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

Defense Environmental Cleanup Technol. Devel. |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

Energy |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energya |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

Fossil Energy R&D |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

Nuclear Energy |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

Electricity Delivery R&D |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

Cybersec., En. Security, & Emerg. Response R&D |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

Advanced Research Projects Agency–Energy |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

DOE, Total |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

Source: DOE FY2019 congressional budget justification, https://www.energy.gov/cfo/downloads/fy-2019-budget-justification. The FY2019 House, Senate, and Enacted columns will be completed as Congress acts on appropriations legislation.

Note: Totals may differ from the sum of the components due to rounding.

a. Excluding Weatherization and Intergovernmental Activities.

b. Does not include rescission of $240 million in prior-year balances.

c. Included with Electricity Delivery R&D in FY2017 appropriations act.

National Aeronautics and Space Administration53

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) was created in 1958 by the National Aeronautics and Space Act (P.L. 85-568) to conduct civilian space and aeronautics activities. NASA has research programs in planetary science, Earth science, heliophysics, astrophysics, and aeronautics, as well as development programs for future human spacecraft and for multipurpose space technology such as advanced propulsion systems. In addition, NASA operates the International Space Station (ISS) as a facility for R&D and other purposes.

Because final FY2018 funding was not available at the time the FY2019 budget was prepared, requested funding is compared to the FY2017 actual funding.

The Administration is requesting about $16.474 billion for NASA R&D in FY2019. This is 1.6% less than the FY2017 level of about $16.743 billion. For a breakdown of these amounts, see Table 11. NASA R&D funding comes through five accounts: Science; Aeronautics; Exploration Research and Technology (formerly Space Technology); Deep Space Exploration Systems (formerly Exploration); and the ISS, Commercial Crew, and Commercial Low Earth Orbit (LEO) Development portions of LEO and Spaceflight Operations (formerly Space Operations).

The FY2019 request for Science is $5.895 billion, an increase of 2.3% relative to FY2017. Within this total, funding for Earth Science would decrease by $124 million (6.5%); funding for Planetary Science would increase by $407 million (22.3%); and funding for Astrophysics would decrease by $167 million (12.3%). The request for Earth Science assumes the termination of three items in the Earth Systematic Missions program: the Pre-Aerosol, Clouds, and Ocean Ecosystem (PACE) mission; the Climate Absolute Radiance and Refractivity Observatory (CLARREO) Pathfinder mission; and the NASA-provided instruments on the Deep Space Climate Observatory (DSCOVR) mission. These were also proposed for termination in the FY2018 budget; Congress funded them for FY2018 in legislation enacted after the release of the FY2019 budget. The proposed increase for Planetary Science includes $90 million in new funding for the Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART), a mission to demonstrate the redirection of an asteroid for the purpose of planetary defense; and an increase of $199 million to fund a new Lunar Discovery and Exploration program, including public-private partnerships for research using commercial lunar landers. In Astrophysics, a proposed decrease of $265 million for the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST, previously a separate budget item) is consistent with that mission's previous plans; a proposed decrease of $100 million for Exoplanet Exploration reflects the proposed cancellation of the Wide Field Infrared Space Telescope (WFIRST).

The FY2019 request for Aeronautics is $634 million, a decrease of 3.4% relative to FY2017. The request includes $88 million (up from $19 million in FY2017) for the Low Boom Flight Demonstrator, intended to demonstrate quiet supersonic flight. This increase would be offset by a decrease of $50 million for the Airspace Operations and Safety program and a $44 million decrease for the Advanced Air Vehicles program.

The FY2019 request for Exploration Research and Technology is $1.003 billion, an increase of 21.3% relative to FY2017. This account supports the Space Technology Mission Directorate, the Human Research Program, and certain activities previously in the Advanced Exploration Systems program. Funding for Technology Maturation would increase by $82 million. Funding for Technology Demonstration would increase by $70 million, but within Technology Demonstration, funding for the Restore-L mission and other in-space robotic satellite servicing activities would decrease by $85 million. Funding for the Human Research Program would be the same as in FY2017.

The FY2019 request for Deep Space Exploration Systems is $4.559 billion, an increase of 9.0% relative to FY2017. This account funds development of the Orion Multipurpose Crew Vehicle and the Space Launch System (SLS) heavy-lift rocket, the capsule and launch vehicle mandated by the NASA Authorization Act of 2010 for future human exploration beyond Earth orbit. The first test flight of SLS carrying Orion but no crew (known as EM-1) is now expected no earlier than December 2019. The first flight of Orion and the SLS with a crew on board (known as EM-2) is now expected in late 2022 or early 2023. Funding for Orion, the SLS, and related ground systems (collectively known as Exploration Systems Development) would decrease by $259 million relative to FY2017. The account also funds Advanced Exploration Systems, which would increase by $791 million relative to FY2017. That increase would include $504 million in new funding for a platform in lunar orbit (known as the Gateway) to serve as a test bed for deep space human exploration capabilities.