Current Situation

Major Players and Market Shares

The federal government has a long history of assisting farmers with obtaining loans for farming. This intervention has been justified at one time or another by many factors, including the presence of asymmetric information among lenders, asymmetric information between lenders and farmers, lack of competition in some rural lending markets, insufficient lending resources in rural areas compared to more populated areas, and the desire for targeted lending to disadvantaged groups (such as small farms or socially disadvantaged farmers).1

Several types of lenders make loans to farmers. Some are government entities or have a statutory mandate to serve agriculture. The one most controlled by the federal government is the Farm Service Agency (FSA) in the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). It receives federal appropriations to make direct loans to farmers and to issue guarantees on loans made by commercial lenders to farmers who do not qualify for regular credit. FSA is a lender of last resort but also of first opportunity, because it targets loans or reserves funds for disadvantaged groups.

The lender with the next-largest amount of government intervention is the Farm Credit System (FCS). It is a cooperatively owned and funded—but federally chartered—private lender with a statutory mandate to serve agriculture-related borrowers only. FCS makes loans to creditworthy farmers and is not a lender of last resort but is a government-sponsored enterprise (GSE). Third is Farmer Mac, another GSE that is privately held and provides a secondary market for agricultural loans. FSA, FCS, and Farmer Mac are described in more detail later in this report.

Other lenders do not have direct government involvement in their funding or existence. These include commercial banks, life insurance companies, individuals, merchants, and dealers.

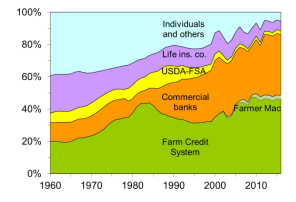

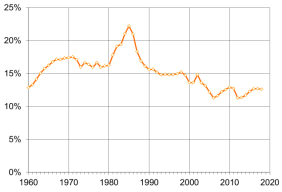

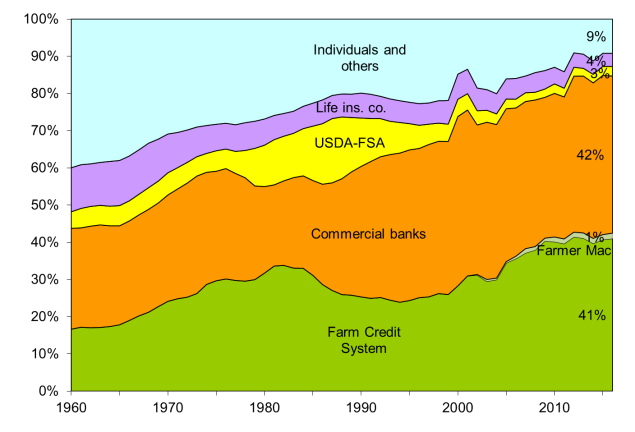

Figure 1 shows that the FCS and commercial banks provide most of the farm credit (41% and 42%, respectively) followed by individuals and others (9.2%) and life insurance companies (3.5%; based on 2016 USDA data, the most recent year with such detail).2 FSA provides about 2.6% of the debt through direct loans. FSA also guarantees about another 4%-5% of the market through loans that are made by commercial banks and the FCS.

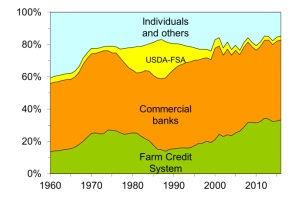

The total amount of farm debt ($374 billion at the end of 2016) is concentrated relatively more in real estate debt (60%) than in non-real estate debt (40%). FCS is the largest lender for real estate (46%), and both commercial banks' and FCS's shares have grown as others' shares have decreased (Figure 2). Commercial banks are the largest lender for non-real estate loans (49%), although FCS has gained share in recent years as the shares by others have decreased (Figure 3).

As the figures show, market shares among these lenders have changed over time. Commercial banks held relatively little farm real estate debt through 1985 but now hold a sizeable amount (Figure 2). The share of loans from "individuals and others" has steadily decreased over time, with fewer private contracts for farm real estate and relatively less dealer financing in operating credits. FSA held a much larger share of farm debt during the farm financial crisis of the 1980s, but that ratio declined as the farm economy improved through the 1990s (Figure 3).

|

Figure 1. Market Shares by Lender of Total Farm Debt, 1960-2016 |

|

|

Source: CRS, using USDA Economic Research Service (ERS) year-end data at http://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/farm-income-and-wealth-statistics.aspx. Notes: Shares in the graph are for direct loans. Guarantees issued on other lenders' loans are not shown. FSA issued guarantees on about 4%-5% of farm loans that are not shown separately but are included in the shares of commercial banks and the Farm Credit System. ERS began publishing data on Farmer Mac in 2002. |

The Farm Balance Sheet

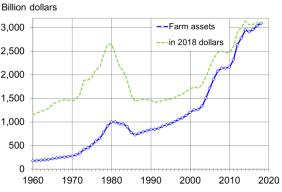

As a whole, farm sector assets have remained strong despite pressure on other real estate sectors. The value of farm assets has grown steadily since the end of the 1980s, particularly since 2003. At the end of 2017, farm sector assets totaled $3.04 trillion. In 2018, USDA forecasts that farm assets will increase 1.6% (Figure 4). The Federal Reserve has found declining land values in recent years but a small recovery through 2017.3 Total farm assets now exceed the previous peak from 1980 in inflation-adjusted terms. Real estate is about 83% of the total amount of farm assets; machinery and vehicles are the next-largest category at about 8% of the total.4

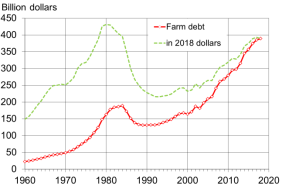

Farm debt reached a historic high of $385 billion at the end of 2017 (Figure 5). USDA forecasts that debt will increase 1% in 2018. In inflation-adjusted terms, however, this level of debt is still well below the peak debt levels of the 1980s.

Debts and assets can be compared in a single measure by dividing debts by assets—the debt-to-asset ratio. A lower debt-to-asset ratio generally implies less financial risk to the sector than a higher ratio. Farm debt-to-asset ratio levels have declined fairly steadily since the late 1980s after the farm financial crisis and reached a historic low of 11.3% in 2006. When farm asset growth paused in 2009-2010, the debt-to-asset ratio rose slightly to 12.9% (Figure 6). After returning to a historic low in 2012, the debt-to-asset ratio rose to 12.7 in 2017 and is forecasted to remain steady in 2018. But as a whole, farms are not as highly leveraged as they were in the 1980s.

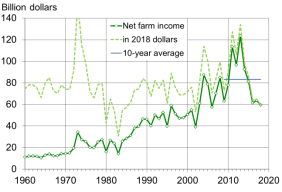

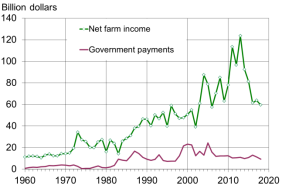

Net farm income has become more variable, especially since 2000. After reaching then-historic highs in 2004, net farm income fell by a third in two years (Figure 7). After peaking again in 2008, net farm income fell by 25% in 2009. New net farm income highs were set in 2011 and 2013, but USDA's February 2018 forecast of $60 billion would be a 52% decline from 2013.5 The relatively low net farm income forecasted for 2018 is 29% below the 10-year average.6

Government payments to farmers have also risen from decades ago but do not always offset the variability in net farm income. Fixed direct payments that were not tied to prices or revenue were the primary form of government payments in recent years. These payments supported farm income but did not necessarily help farmers manage risks. Figure 8 shows that more of net farm income is coming from the market rather than the government compared to the 1980s.

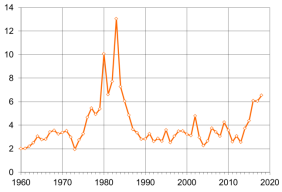

Another indicator of leverage compares debt to net farm income. A lower debt-to-income ratio (with the ratio expressing the number of years of current income that debt represents) implies less financial risk. The farm-debt-to-net-farm-income ratio is more variable than the debt-to-asset ratio. It reached a 35-year low of 2.3 in 2004 and rose to 4.3 in 2009 before falling again to 2.5 in 2013. However, the decline in net farm income into 2018 has caused it to rise to a ratio of over 6, not seen since the 1980s. This is outside the typical range of 2-4 over the past 50-years and is leading to an observed rise in repayment risk7 (Figure 9).

|

|

|

||||||

|

|

|

||||||

|

|

|

Delinquency Rates on Farm Loans

While the global financial crisis in 2008-2009 was slower to affect the balance sheets of farmers and agricultural lenders than the housing market, its presence was observed in agricultural lending. Credit standards were tightened (more documentation and oversight of loans was required), and lenders sometimes made less credit available to producers. As the lender of last resort, the FSA experienced significantly higher demand for its direct loans and guarantees.

In 2007, 2008, and 2010, farm commodity prices were particularly high, supporting farm income at above-average levels. But in 2006 and 2009, net farm income fell by about one-third (Figure 7), reducing some farmers' ability to repay loans, particularly in some farm sectors such as dairy, hogs, and poultry. Strong farm income from 2011 to 2013 improved most farmers' ability to repay loans. But weakness in farm income since 2014 has increased pressure on some farmers' repayment capacity.

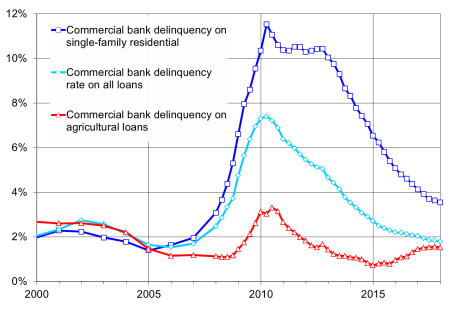

Delinquency rates include loans that are 30 days or more past due and still accruing interest, as well as those in nonaccrual status. The delinquency rates on residential mortgages and all loans appear to have reached a recent peak in mid-2010 (11.5% for residential mortgages and 7.4% for all commercial bank loans, Figure 10). The delinquency rates for agricultural loans did not begin to rise until mid-2008 after continuing to fall to historic lows while delinquencies were rising in residential mortgages and other loans. Moreover, the rate of increase in delinquencies on farm production loans at commercial banks was not as sharp as in the non-farm sectors and peaked in June 2010 at 3.3%. Delinquency rates on farm production loans at commercial banks returned to historic lows below 1% but have risen slightly since 2015 and appear to have stabilized in 2017.8

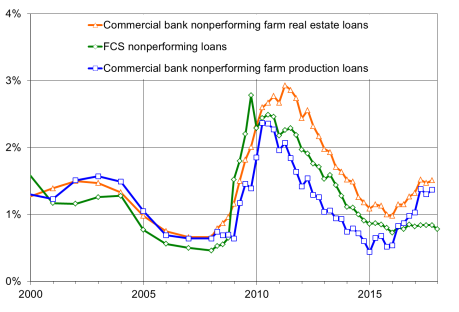

A more severe measure of loan performance is nonperforming loans. Nonperforming loans include nonaccrual loans and accruing loans 90 days or more past due. These loans are more in jeopardy than delinquent loans and represent a smaller subset of loans. Within the agricultural loan portfolio, the FCS nonperforming loan rate has maintained the levels of the mid-2000s that indicated that the system had recovered from the farm financial crisis of the 1980s. FCS nonperforming loans rose from 0.5% at the beginning of 2008 to a near-term peak of 2.8% on September 30, 2009, before decreasing to 0.73% at the end of 2015. While FCS nonperforming loans have risen slightly in 2016 and 2017, they remain below 0.85% into 2018 (Figure 11).9

At commercial banks, nonperforming farm loans rose during the 2008-2010 financial crisis, recovered into 2015, but have risen again as declining farm income has stressed repayment. Nonperforming farm real estate loans at commercial banks rose from a low of 0.7% in December 2006 to 2.9% in March 2011 before declining to 1% as of December 31, 2015. Nonperforming farm production loans rose from a low of 0.6% in December 2006 to 2.4% in March 2010 before declining again to 0.4% as of December 31, 2014 (Figure 11). Nonperforming loan rates at commercial banks have risen for farm real estate loans and farm production loans to about 1.5% and 1.3%, respectively, at the end of 2017.10

|

Figure 10. Delinquency Rates on Commercial Bank Loans, 2000-2017Q4 |

|

|

Source: Compiled by CRS. Data through December 31, 2017, using Federal Reserve Bank, "Delinquency Rates on Loans at Commercial Banks" (seasonally adjusted), http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/chargeoff. Notes: Delinquencies include loans that are 30 days or more past due and still accruing interest, as well as those in nonaccrual status. The amounts are percentages of end-of-period loans. |

|

|

Source: Compiled by CRS. Federal Farm Credit Banks Funding Corporation data through December 31, 2017, http://www.farmcredit-ffcb.com. Federal Reserve Bank, Agricultural Finance Data Book, Tables B.2 and B.4, through September 30, 2017, https://www.kansascityfed.org/research/indicatorsdata/agfinancedatabook. Notes: Nonperforming loans include nonaccrual loans and accruing loans 90 days or more past due. The amounts are percentages of total loans. |

Description of Government-Related Farm Lenders

USDA Farm Service Agency (FSA)

FSA is considered a lender of last resort because it makes direct farm ownership and operating loans to family-sized farms that are unable to obtain credit elsewhere. FSA also guarantees timely payment of principal and interest on qualified loans made by commercial banks and the FCS. Farm bills modify the permanent authority in 7 U.S.C. 1921.

In FY2017, an appropriation of $90 million in budget authority (plus $317 million for salaries and expenses) supported $8 billion of new direct loans and guarantees.11 Direct loans are limited to $300,000 per borrower ($50,000 for microloans), and guaranteed loans to $1,399,000 (adjusted for inflation). Direct emergency loans are available for disasters.12

Part of the FSA loan program is reserved for beginning farmers and ranchers (7 U.S.C. 1994 (b)(2)). For direct loans, 75% of the funding for farm ownership loans and 50% of operating loans are reserved for the first 11 months of the fiscal year. For guaranteed loans, 40% is reserved for ownership loans and farm operating loans for the first half of the fiscal year. Funds are also targeted to "socially disadvantaged" farmers by race, gender, and ethnicity (7 U.S.C. 2003). Using these provisions, FSA is also known as lender of first opportunity for many borrowers.13

Farm Credit System (FCS)

Congress established the FCS in 1916 to provide a dependable and affordable source of credit to rural areas at a time when commercial lenders avoided farm loans. The FCS is neither a government agency nor guaranteed by the U.S. government but is a network of borrower-owned lending institutions operating as a GSE. It is not a lender of last resort; it is a for-profit lender with a statutory mandate to serve agriculture. Funds are raised through the sale of bonds on Wall Street. Four large banks allocate these funds to 69 credit associations that, in turn, make loans to eligible creditworthy borrowers.

Statutes and oversight by the House and Senate Agriculture Committees determine the scope of FCS activity (Farm Credit Act of 1971, as amended; 12 U.S.C. 2001 et seq.). Benefits such as tax exemptions are also provided. Eligibility is limited to farmers, certain farm-related agribusinesses, rural homeowners in towns under 2,500 population, and cooperatives.14 The federal regulator is the Farm Credit Administration (FCA).15

Farmer Mac

Farmer Mac is a separate GSE that is a secondary market for agricultural loans. Some consider it related to the FCS in that FCA is its regulator and that it was created by the same legislation, but it is financially and organizationally a separate entity. Farmer Mac purchases mortgages from lenders and guarantees mortgage-backed securities that are bought by investors.

Recent Congressional Issues for Agricultural Credit

Competition Between Farm Credit System and Commercial Banks

The FCS is unique among the GSEs because it is a retail lender making loans directly to farmers and thus is in direct competition with commercial banks. Because of this direct competition for creditworthy borrowers, the FCS and commercial banks often have an adversarial relationship in the policy realm. Commercial banks assert unfair competition from the FCS for borrowers because of tax advantages that can lower the relative cost of funds for the FCS.16 They often call for increased congressional oversight. The FCS counters by citing its statutory mandate (and limitations) to serve agricultural borrowers in good times and bad times.17

In contrast, FSA's loan programs are supported by both the FCS and commercial banks. FSA is not regarded as a competitor since it serves farmers who otherwise may not be able to obtain credit. Commercial banks and the FCS particularly support the FSA loan guarantee program because it allows them to make and service loans that otherwise might not be possible or at reduced risk.

Credit Title in the Farm Bill

Credit issues are not expected to be a major part of a farm bill in 2018 or to be particularly significant in the overall scope of the permanent agricultural credit statutes. Nonetheless, several issues could arise, such as (1) further targeting of FSA lending resources to beginning, socially disadvantaged, and/or veteran farmers and (2) raising the maximum loan size per borrower.

The enacted 2014 farm bill (P.L. 113-79) made relatively small policy changes to USDA's permanently authorized farm loan programs. It gave USDA discretion to recognize alternative legal entities and allowed alternatives to meet a farming experience requirement. It increased the maximum size of down-payment loans and eliminated term limits on guaranteed operating loans, among other changes.18

Maximum Loan Size per Borrower

For the FSA farm loan program, the maximum loan size per borrower for direct loans is $300,000 (7 U.S.C. 1925(a)(2) for farm ownership loans, and 7 U.S.C. 1943(a)(1) for farm operating loans). It was last increased in the 2008 farm bill from $200,000. For FSA guaranteed loans, the maximum size per borrower is presently $1,399,000, which is a $700,000 base amount in statute increased annually by an inflation factor (same U.S. Code sections as for direct loans). It was last updated in statute in 1998, when the inflation factor was added.

As the average size of farms has increased and farms have become more capital intensive, these loan limits may increasingly be seen as limiting opportunities for some farmers. Two bills in the 115th Congress would raise these limits:

- S. 1736 would raise the maximum size of direct loans to $600,000. It would raise the maximum size of guaranteed loans to $2.5 million, indexed for inflation.

- S. 1921 would similarly raise the maximum size of direct loans to $600,000. It would raise the maximum size of guaranteed loans to $3 million, indexed for inflation. The bill would also update and increase the overall program authorization levels and provide mandatory funding. The FSA farm loan program has historically been funded with discretionary appropriations.

Term Limits on USDA Farm Loans

Congress added "term limits" to the USDA farm loan program in 1992 and 1996 to restrict eligibility for government farm loans and encourage farmers to "graduate" to commercial loans. The term limits place a maximum number of years that farmers are eligible for certain types of FSA loans or guarantees. However, until the end of 2010, Congress had suspended enforcement of term limits on guaranteed operating loans to prevent some farmers from being denied credit, and the 2014 farm bill eliminated that term limit (Table 1).

Table 1. Term Limits on Farm Service Agency Loans

Maximum number of years that farmers are eligible for loans

|

Type of FSA Loan |

Direct loans term limits |

Guaranteed loans term limits |

|

Farm Operating Loans |

6 years, plus possible 2-year extensiona |

No term limitb |

|

Farm Ownership Loans |

10 yearsc |

No term limitd |

Source: CRS, based on statute and unpublished USDA data.

Note: Term limits are separate from the maximum maturity or duration of an individual loan, which may be as long as 40 years for a farm ownership loan or as short as one year for a farm operating loan.

a. Direct operating loans are limited to a six-year period. In certain cases, borrowers may qualify for a one-time, two-year extension (7 U.S.C. 1941(c)(1)(C) and (c)(4)). In June 2009, USDA said that about 4,800 FSA borrowers were limited to one more year, and another 7,800 borrowers were limited to two more years. USDA did not expect many to graduate to commercial credit (FSA Administrator, testimony to the House Agriculture Subcommittee on Conservation, Credit, Energy and Research, June 11, 2009).

b. Prior to the 2014 farm bill, guaranteed operating loans were limited to a 15-year period (former 7 U.S.C. 1949(b)(1)). However, enforcement of that term limit was suspended by statute until December 31, 2010. Upon expiration of the suspension, the 15-year term limit was enforced from 2011 to 2013. In December 2010, USDA had said that about 1,600 borrowers had reached the guaranteed term limit. The 2014 farm bill permanently removed this term limit (P.L. 113-79 §5107).

c. A borrower is eligible for direct farm ownership (real estate) loans for a maximum of 10 years after the first loan is made (7 U.S.C. 1922(b)(1)(C)).

d. FSA, Evaluating the Relative Cost Effectiveness of the Farm Service Agency's Farm Loan Programs, report to Congress, August 2006, p. 76, http://www.fsa.usda.gov/Internet/FSA_File/farm_loan_study_august_06.pdf.