Introduction

The United States has gradually shifted its formal drug policy from a punishment-focused model1 toward a more comprehensive approach—it is now one that focuses on prevention, treatment, and enforcement. The Obama Administration stated that it coordinated "an unprecedented government-wide public health and public safety approach to reduce drug use and its consequences."2 In its FY2018 budget request, the Trump Administration requested funds for both public health and public safety efforts to combat the opioid epidemic.3

The proliferation of drug courts in American criminal justice fits this new comprehensive model. Broadly, these specialized court programs are designed to divert some individuals away from traditional criminal justice sanctions such as incarceration. Many drug courts offer a treatment and social service alternative for those who otherwise may have faced traditional criminal sanctions for their offenses. In some drug courts, individuals that have been arrested are diverted from local courts into special judge-involved programs; these courts are often viewed as "second chance" courts. Other drug court programs offer reentry assistance after an offender has served his or her sentence. According to some research, these courts help save on overall criminal justice costs, provide treatment for defendants/offenders with substance abuse issues, and help offenders avoid rearrest.4

This report will explain (1) the concept of a "drug court," (2) how the term and programs have expanded to include wider meanings and serve additional subgroups, (3) how the federal government supports drug courts, and (4) research on the impact of drug courts on offenders and court systems. In addition, it briefly discusses how drug courts might provide an avenue for addressing the opioid epidemic and other emerging drug issues that Congress may consider.

What are Drug Courts?

The term "drug courts" refers to specialized court programs that present an alternative to the traditional court process for certain criminal defendants5 and offenders. Traditionally, these individuals are first-time, nonviolent offenders who are known to abuse drugs and/or alcohol. While there are additional specialized goals for different types of drug courts (e.g., veterans drug courts, tribal drug courts, and family drug courts), the overall goals of adult and juvenile drug courts are to reduce recidivism and substance abuse.

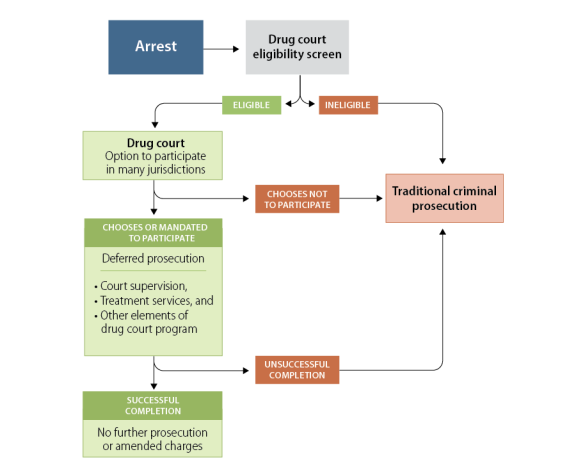

Drug court programs may exist at various points in the justice system, but they are often employed postarrest as an alternative to traditional criminal justice processing. Figure 1 illustrates a deferred prosecution, pretrial drug court model where defendants are diverted into drug court prior to pleading to a criminal charge. In many drug court programs, participants have the option to participate in the program.

|

|

Source: CRS illustration of pretrial, deferred-prosecution drug court model. Notes: The defendant does not have to enter a plea to charges under this drug court model. For an example of a pretrial model involving a deferred prosecution drug court program, see the Felony Pre-Trial Intervention Program operated by the Florida Department of Corrections, http://www.sao17.state.fl.us/felony-pti.html. |

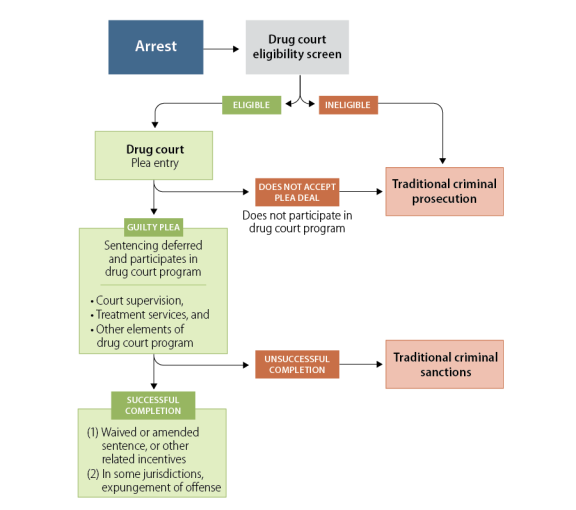

Figure 2 illustrates a postadjudication model where defendants must plead guilty to charges (as part of a plea deal) in order to participate in the drug court program. Upon completion of this type of program, their sentences may be amended or waived, and in some jurisdictions, their offenses may be expunged.

|

|

Source: CRS illustration of postadjudication drug court model. Notes: For an example of a postadjudication model involving a guilty plea of the offender, see the Denver Drug Court of Denver, CO, http://www.denverda.org/prosecution_units/Drug_Court/Drug_Court.htm. |

These diagrams illustrate two common models of drug courts, but other models (or variations on the above) have been developed around the country. For example, some drug court referrals may come as a condition of probation. Many drug courts, including some federal drug court programs, are actually reentry programs that assist a drug-addicted prisoner with reentering the community while receiving treatment for substance abuse.

While drug courts vary in composition and target population, they generally have a comprehensive model involving

- offender screening and assessment of risks and needs,

- judicial interaction,

- monitoring (e.g., drug and alcohol testing) and supervision,

- graduated sanctions and incentives, and

- treatment and rehabilitation services.6

Drug courts are usually managed by a team of individuals from (1) criminal justice,7 (2) social work, and (3) treatment service.8

Drug courts typically utilize a multiphase treatment approach including a stabilization phase, an intensive treatment phase, and a transition phase. The stabilization phase may include a period of detoxification, initial treatment assessment, and education, as well as additional screening for other needs. The intensive treatment phase typically involves counseling and other therapy. Finally, the transition phase could emphasize a variety of reintegration components including social integration, employment, education, and housing.9

Expansion of Drug Courts

A group of criminal justice professionals established the first drug court in Florida in 1989; they are credited with sparking a national movement of problem-solving courts that address specific needs and concerns of certain types of offenders.10 There are around 3,000 drug courts (of various types) operating in the United States.11 Drug courts have diversified to serve specialized groups including veterans, juveniles, and college students. Many drug courts are hybrid courts and address issues beyond drug abuse including mental health and alcohol-impaired driving. In some ways, the term "drug courts" appears to be a catch-all phrase for specialized programs for addicted defendants and offenders at various points in the criminal justice process.

Federal Drug Courts

While the Judicial Conference of the United States has long opposed the creation of specialized federal courts,12 there has been growing support within the federal court system and the Department of Justice (DOJ) for reentry programs that incorporate some features of drug courts.13 While some federal district courts have created special programs for drug-involved offenders—these programs are sometimes referred to as "drug courts"—they are largely reentry programs that manage an inmate's reintegration to the community. A few federal drug court programs, however, manage offenders with "front end" diversion options. There have been questions about the effectiveness of drug court programs at the federal level due to the nature of federal crimes and the individuals who are arrested for allegedly committing them.

Federal district courts fund these specialized programs from decentralized allotments14 given to the districts for general treatment and supervision of offenders.15 As federal districts have budget autonomy, they may elect to establish these specialized court programs.16

Of note, in 2017 the President's Commission on Combating Drug Addiction and the Opioid Crisis recommended that DOJ establish a federal drug court in every federal judicial district.17

Federal Drug Courts and the 21st Century Cures Act

Enacted in 2016, Section 14003 of the 21st Century Cures Act (the Cures Act; P.L. 114-255) required DOJ to establish a pilot program to determine the effectiveness of federal drug and mental health courts. Within one year of enactment, DOJ, with assistance from the Administrative Office of the United States Courts and the United States Probation Offices, must establish a pilot program in at least one U.S. judicial district18 that will divert certain offenders with mental illness or intellectual disabilities from federal prosecution, probation, or prison and place the offenders in these specialized courts. As of January 2018, this pilot program is still in the planning stages.19

Veterans Treatment Courts

Postdeployment, many veterans face unique challenges in readjusting to civilian life, and these challenges may contribute to involvement with the criminal justice system. According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics' (BJS's) National Inmate Survey from 2011 to 2012, approximately 8% (181,500) of the total incarcerated population in the United States20 are veterans.21 For approximately 14% (25,300) of these incarcerated veterans, the most serious offense that led to their incarceration was a drug offense, and for approximately 4% (7,100), their most serious offense was driving while intoxicated or impaired.22 Older BJS survey data indicate that 43% of veteran state prisoners and 46% of veteran federal prisoners met the criteria for drug dependence or abuse in 2004, as opposed to 55% of nonveteran state prisoners and 45% of nonveteran federal prisoners.23 While veterans in state prison reported lower levels of past drug use than nonveterans, a larger percentage of veterans (30%) than nonveterans (24%) reported a "recent history of mental health services."24

In 2008, the first veterans court was created in Buffalo, NY, in response to the combined mental health and substance abuse treatment needs of justice system-involved veterans.25 These court programs are a hybrid model of drug treatment and mental health treatment courts.26 As of June 2015, there were approximately 306 veterans treatment courts and 6 federal veterans courts.27

Federal Support for Drug Courts

The federal government has demonstrated growing support for the drug court model primarily through financial support of drug court programs, research, and various drug court initiatives.

Drug Court Discretionary Grant Program

The Department of Justice (DOJ) supports research on drug courts,28 training and technical assistance for drug courts, and grants for their development and enhancement. The primary federal grant program that supports them is the Drug Court Discretionary Grant Program (Drug Courts Program).29 DOJ's Office of Justice Programs (OJP), Bureau of Justice Assistance (BJA) jointly administers this competitive grant program along with the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration (SAMHSA) within the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Grants are distributed to state, local, and tribal governments as well as state and local courts themselves to establish and enhance drug courts for nonviolent offenders with substance abuse issues.30 See Table 1 for a five-year history of DOJ appropriations for the Drug Courts Program.

Table 1. Enacted Funding under DOJ for the Drug Court Discretionary Grant Program and Veterans Treatment Courts, FY2013-FY2017

(Dollars in millions)

|

FY2013 |

FY2014 |

FY2015 |

FY2016 |

FY2017 |

|

|

Drug Court Discretionary Grant Program |

$38.1a |

$40.5 |

$41.0 |

$42.0 |

$43.0b |

|

Veterans Treatment Courts |

$3.7a |

$4.0 |

$5.0 |

$6.0 |

$7.0b |

Source: FY2013 postsequestration amounts were provided by the Department of Justice. FY2014 enacted amounts were taken from the joint explanatory statement to accompany P.L. 113-76. FY2015 enacted amounts were taken from the joint explanatory statement to accompany P.L. 113-235. FY2016 enacted amounts were taken from the joint explanatory statement to accompany P.L. 114-113. FY2017 enacted amounts were taken from the joint explanatory statement to accompany P.L. 115-31.

a. The FY2013 amounts include rescissions of FY2013 budget authority and the amount sequestered per the Budget Control Act of 2011 (P.L. 112-25).

b. For FY2017, funding for this program was provided under the Opioid Initiative, which included other drug control-related activities.

Drug courts funded through this program may not use federal funding and matched funding to serve violent offenders. Offenders may be characterized as "violent" according to current or past convictions as well as current charges.31 Of note, an exception to the violent offender restriction is made for veterans treatment courts that are funded through the Drug Courts Program.

Grants for Veterans Treatment Courts

Since FY2013, BJA has funded the Veterans Treatment Court Program32 through the Drug Courts Program using funds specifically appropriated for this purpose (see amounts in Table 1). As mentioned, these amounts are not subject to the violent offender exclusion according to BJA.33 The purpose of the Veterans Treatment Court Program is "to serve veterans struggling with addiction, serious mental illness, and/or co-occurring disorders."34 Grants are awarded to state, local, and tribal governments to fund the establishment and development of veterans treatment courts. While veterans treatment court grants have been part of OJP's Drug Courts Program for several years, the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act of 2016 (CARA; P.L. 114-198), authorized DOJ to award grants to state, local, and tribal governments to establish or expand programs for qualified veterans,35 including veterans treatment courts, peer-to-peer services, and treatment, rehabilitation, legal, or transitional services for incarcerated veterans.

Based on a review of program activity at the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), the VA does not offer funding for veterans treatment courts; however, the VA operates a Veterans Justice Outreach (VJO) program,36 which provides outreach and linkage to VA services for justice system-involved veterans, including those involved with veterans courts or drug courts.

Other Grant Support

Other DOJ grants, including the Edward Byrne Memorial Justice Assistance Grants (JAG)37 and Juvenile Accountability Block Grants (JABG),38 may be used to fund drug courts. One of the broader purpose areas of the JAG program is to improve prosecution and courts programs as well as drug treatment programs. The JABG program includes a purpose area to establish juvenile drug courts. Of note, the last time JABG received an appropriation was in FY2013, and it has been unauthorized since it expired in FY2009.

The Office of National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP), under its Other Federal Drug Control Programs account, offers drug court training and technical assistance grants, as well as support for other initiatives.39

As mentioned, SAMHSA jointly administers the Drug Courts Program with BJA. In addition, SAMHSA administers other grants that support drug courts.40 Grants go toward the creation, expansion, and enhancement of adult and family drug courts and treatment drug courts.41 For FY2016, SAMHSA funded 122 drug court continuations, 60 new drug court grants,42 and four contracts. In FY2017, SAMHSA planned to fund 103 drug court continuations, 71 new drug court grants, and two contracts.43

|

FY2013 |

FY2014 |

FY2015 |

FY2016 |

FY2017 |

|

$39.40 |

$52.75 |

$50.00 |

$60.00 |

$58.00 |

Source: Enacted funding data for FY2014-FY2016 taken from the FY2015 and FY2016 operating plans for SAMHSA and enacted funding data for FY2013 and FY2017 provided by SAMHSA. Of note, funding for drug courts is taken from the appropriations line item, "criminal justice activities."

Notes: According to SAMHSA, funding goes toward the following agencies/programs to support drug courts: (1) DOJ, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (OJJDP); (2) Partnership with Robert Wood Johnson for four years; (3) DOJ, BJA, Drug Court Discretionary Grant Program; (4) SAMHSA, Children Affected by Methamphetamine/Family Treatment Drug Court Program; and (5) SAMHSA, Grants to Develop and Expand Behavioral Health Treatment Court Collaborative.

Impact of Drug Courts

Jurisdictions have sought to utilize drug courts to treat individuals' drug addictions, lower recidivism rates for drug-involved offenders, and lower costs associated with processing these defendants and offenders. Since the inception of drug courts, a great deal of research has been done to evaluate their effectiveness and their impact on offenders, the criminal justice system, and the community. Much of the research yields positive outcomes.44

Over the last decade, the National Institute of Justice, through its CrimeSolutions.gov evaluation program, has evaluated 21 drug court programs and found that 19 of them had either "effective" or "promising" ratings while two had ratings of "no effects." Most reported positive results for recidivism outcomes. For cost evaluations, only some programs had these data and these evaluations showed mixed results. Some programs showed significant cost savings while others had insignificant findings for cost impacts.45

Several studies have demonstrated that drug courts may lower recidivism rates and/or lower costs for processing defendants and offenders compared to traditional criminal justice processing.46 For example, one group of researchers examined the impact of a drug court over 10 years and concluded that treatment and other costs associated with the drug court (investment costs)47 per offender were $1,392 less than investment costs of traditional criminal justice processing. In addition, savings due to reduced recidivism (outcome costs) for drug court participants were more than $79 million over the 10-year period.48 A collaboration of researchers conducted a five-year longitudinal study of 23 drug courts from several regions of the United States and reported that drug court participants were significantly less likely than nonparticipants to relapse into drug use and participants committed fewer criminal acts than nonparticipants after completing the drug court program.49

Still, some are skeptical of the impact of drug courts. The Drug Policy Alliance50 has claimed that drug courts help only offenders who are expected to do well and do not truly reduce costs. This organization also has criticized drug courts for punishing addiction because drug courts dismiss those who are not able to abstain from substance use.51

Selected Issues for Congress

The Opioid Epidemic

Congress has long been concerned over illicit drug use and abuse in the United States. Recently, Congress has given attention to opioid abuse, and especially overdose deaths involving prescription and illicit opioids.52 In 2015, there were 52,404 drug overdose deaths in the United States, including 33,091 (63.1%) that involved an opioid.53 Also, in 2016 SAMHSA estimated that 329,000 Americans age 12 and older were current users54 of heroin and approximately 3.8 million Americans were current "misusers"55 of prescription pain relievers.56 Policymakers may debate whether drug courts are an effective tool in the package of federal efforts to address the opioid epidemic. Policy options include, but are not limited to, increasing federal funding for drug courts, expanding federal drug court programs, and amending the Drug Courts Program to possibly include a broader group of offenders, among other potential changes.

Inclusion of Violent Offenders

As discussed, grant recipients of the federal Drug Courts Program, with the exception of veterans treatment courts, must exclude violent offenders;57 however, some argue that drug courts should include violent offenders. One group of researchers compared the outcomes for violent and nonviolent offenders and concluded that courts should consider the current charge rather than the offender's history of violence, and the type and seriousness of the offender's substance abuse problem when selecting individuals for drug court programs.58 They found that while it appeared that individuals with a history of violence (defined as at least one violent charge before entering drug court) were more likely to fail the program than those who never had been charged with a violent crime, the relationship between history of violence and drug court success disappeared when controlling for total criminal history.59 More serious offenders are less likely than low-level or first-time offenders to abstain from crime, and some argue that drug courts may be the best option for these individuals.

Substance abuse and crime have long been linked,60 and diversion and treatment may assist some individuals in avoiding criminal behavior. Congress may wish to maintain the exclusion of violent offenders from the Drug Courts Program, or it may consider broadening the pool of eligible offenders that may participate in BJA-funded drug court programs to include certain violent offenders.