Overview

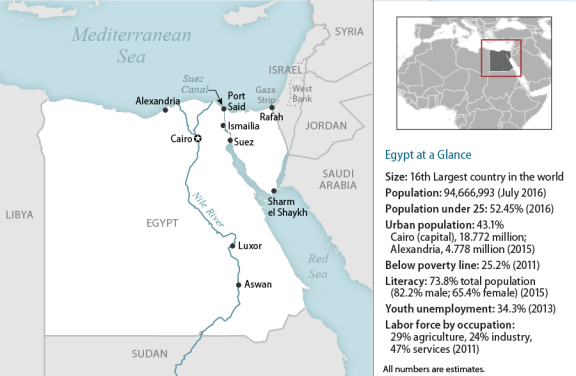

Historically, Egypt has been an important country for U.S. national security interests based on its geography, demography, and diplomatic posture. Egypt controls the Suez Canal, which is one of the world's most well-known maritime chokepoints, linking the Mediterranean and Red Seas.1 In 2016, nearly 4 billion barrels per day of crude oil transited the canal in both directions.2

|

|

Source: Created by CRS |

Egypt, with its population of 94.7 million, is by far the most populous Arabic-speaking country.3 Although it may not play the same type of leading political or military role in the Arab world as it has in the past, Egypt may retain some "soft power" by virtue of its history, its media, and its culture. The 22-member Arab League is based in Cairo, as is Al Azhar University, which claims to be the oldest continuously operating university and has symbolic importance as a leading source of Islamic scholarship.

Additionally, Egypt's 1979 peace treaty with Israel remains one of the most significant diplomatic achievements for the promotion of Arab-Israeli peace. While people-to-people relations remain cold, Israel and Egypt have increased their cooperation against Islamist militants and instability in the Sinai Peninsula and Gaza Strip.

Historical Background

Since 1952, when a cabal of Egyptian Army officers, known as the Free Officers Movement, ousted the British-backed king, Egypt's military has produced four presidents; Gamal Abdel Nasser (1954-1970), Anwar Sadat (1970-1981), Hosni Mubarak (1981-2011), and Abdel Fattah el Sisi (2013-present). In general, these four men have ruled Egypt with strong backing from the country's security establishment. The only significant and abiding opposition has come from the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood, an organization that has opposed single party military-backed rule and advocated for a state governed by a vaguely articulated combination of civil and Shariah (Islamic) law.

Egypt's sole departure from this general formula took place between 2011 and 2013, after popular demonstrations sparked by the "Arab Spring" that had started in neighboring Tunisia compelled the military to force the resignation of former President Hosni Mubarak in February 2011. During this period, Egypt experienced tremendous political tumult, culminating in the one-year presidency of the Muslim Brotherhood's Muhammad Morsi, from June 2012 to July 2013. When Morsi took office on June 30, 2012, after winning Egypt's first truly competitive presidential election, his ascension to the presidency was supposed to mark the end of a rocky 16-month transition period. Proposed time lines for elections, the constitutional drafting process, and the military's relinquishing of power to a civilian government had been constantly changed, contested, and sometimes even overruled by the courts. Instead of consolidating democratic or civilian rule, Morsi's rule exposed the deep divisions in Egyptian politics, pitting a broad cross-section of Egypt's public and private sectors, the Coptic Church, and the military against the Brotherhood and its Islamist supporters.

The atmosphere of mutual distrust, political gridlock, and public dissatisfaction that permeated Morsi's presidency provided Egypt's military, led by then-Defense Minister Sisi, with an opportunity to reassert political control. On July 3, 2013, following several days of mass demonstrations against Morsi's rule, the military unilaterally dissolved Morsi's government, suspended the constitution that had been passed during his rule, and installed an interim president. The Muslim Brotherhood and its supporters declared the military's actions a coup d'etat and protested in the streets. Weeks later, Egypt's military and national police launched a violent crackdown against the Muslim Brotherhood, and police and army soldiers fired live ammunition against demonstrators encamped in several public squares, resulting in the killing of at least 1,150 demonstrators. The Egyptian military justified these actions by decrying the encampments as a threat to national security.

Egypt under President Sisi: 2014-Present

Egyptian President Abdel Fattah el Sisi (former Field Marshal and Minister of Defense) has somewhat restored the public order that was upended by nationwide protests and leadership changes from 2011 to 2013. Critics charge that authorities have established order by rolling back civil liberties and curtailing most political opposition.4 In public, President Sisi, who was elected in mid-2014 with 97% of the vote, has stated that Egyptians must defer practicing "real democracy" in order to preserve the "current social consensus."5

|

|

Source: Egyptian State Information Service |

The 2018 Presidential Election

President Sisi is standing for reelection in Egypt's upcoming March 26-28 presidential election against a relatively unknown politician (Mousa Mostafa Mousa) who, before his last-minute candidacy was announced, was on record as a Sisi supporter.6

Several candidates either withdrew from the race or were forced to withdraw after facing possibly politically motivated criminal charges. Two prominent, Mubarak-era military leaders, Ahmed Shafik (Shafiq) and Lieutenant General Sami Anan, were considered as potential challengers to the president. General Anan, a former chief of the general staff of the armed forces, was arrested three days after declaring his candidacy in January 2018 for breaching the laws of military service by failing to seek the military's permission before declaring his candidacy. Shafik, a former air force general, prime minister, and runner-up in the 2012 presidential election, withdrew from the race in late 2017 after authorities threatened him with allegations of corruption and sexual misconduct.7 Both men may have garnered some support from within the military and intelligence establishment, as well as from the private sector. The withdrawal/arrest of Anan and Shafik follows President Sisi's recent high-profile dismissals of top military and intelligence officials, suggesting that Sisi may be trying to further consolidate his position within the vast but opaque national security establishment.8

With no significant opposition to President Sisi's reelection bid, some have questioned whether Egypt's upcoming election can count as free and fair. A coalition of opposition parties and figures is calling for a boycott of the election using the slogan "stay at home" in order to depress turnout and delegitimize Sisi's rule. On January 23, 2018, Senator John McCain issued a press release concerning Egypt's upcoming election, noting the following:

The 2018 presidential elections offer an important opportunity for the Government of Egypt to include citizens in the political process and reopen the public sphere for real discussion and debate. All candidates for public office should have equal opportunity, including access to media and public space for campaigning. Instead, a growing number of presidential candidates have been arrested and forced to withdraw, citing a repressive climate and fear of further retribution. Without genuine competition, it is difficult to see how these elections could be free or fair.9

That same day, U.S. State Department spokesperson Heather Nauert remarked that "We support a timely and credible electoral process and believe it needs to include the opportunity for citizens to participate freely in Egyptian elections. We believe that that should include addressing restrictions on freedom of association, peaceful assembly, and also expression."10

The Egyptian Government & Economy

Executive Branch and Military

Egypt is formally a republic, governed by a constitution that was approved in a national referendum in January 2014.11 President Sisi, who assumed office in June 2014 after winning a May 2014 election with 96% of the vote, is standing for reelection in 2018 (see above). The constitution limits the president to two four-year terms.12 It also allows the president to issue decrees with the force of law when parliament is not in session, to appoint a prime minister to form a government, and to reshuffle the cabinet with the approval of parliament.

Since 1952, the military has been the strongest government entity, comprising nearly half a million personnel and possessing vast land and business holdings.13 It plays a key social role, aiming to provide employment and a sense of national identity and pride. General Sedki Sobhi is the current Minister of Defense.

Legislative Branch

Parliamentary elections were held in late 2015 (Parliament had been dissolved since June 2012) for Egypt's House of Representatives (or Council of Representatives), with its single-chamber legislature comprised of 596 members (568 elected, 28 appointed by the president). The Support Egypt Coalition (SEC) is a bloc of six parties considered to be the progovernment majority. As of early January 2018, 464 of the 596 members of parliament have endorsed President Sisi for reelection.14 Members of parliament serve five-year terms. The Speaker of the Egyptian House of Representatives is Dr. Ali Abdel Aal Sayyed Ahmed, an expert on constitutional law.

Parliamentarians with Islamist leanings are represented by 12 lawmakers who hail from the Salafist Nour Party. The Muslim Brotherhood was outlawed and declared a terrorist group in 2013 and its main political arm, the Freedom and Justice Party (FJP), was dissolved in 2014.15

In 2017, parliament widely approved legislation endorsed by the executive branch, including a new investment law, a law on national health insurance, and the controversial June 2017 ratification of the maritime border demarcation agreement between Egypt and Saudi Arabia (the transfer of the Red Sea islands of Tiran and Sanafir to Saudi Arabia).16 In summer 2017, Egyptian parliamentarians visited Congress to build interparliamentary ties and call for the U.S. designation of the Muslim Brotherhood as a Foreign Terrorist Organization.17

The Judiciary

Egypt has civilian courts and, since 1966, a parallel military justice system.18 Article 204 of the 2014 constitution enshrines the Military Court as an independent judicial body, and subsequent presidential decrees have expanded its jurisdiction. Article 94 of the 2014 constitution states that "the independence, immunity and impartiality of the judiciary are essential guarantees for the protection of rights and freedoms." Although the professionalism of Egyptian judges has been long established, some observers have asserted that, since 2013, the courts have supported the military's crackdown against dissent.19 In 2017, parliament passed an amendment to the Judicial Authority Law which altered how the chief justice of Egypt's four main judicial bodies is selected. Whereas under the previous system, the chief justice was selected on a seniority basis with presidential approval, the amended law gives the president the authority to choose the chief justice from three nominees sent to him by the courts. Some current and former judges have assailed the new law as undermining the independence of the judiciary.20

The Economy

|

|

Source: Yasser El-Shimy & Anthony Dworkin, "Egypt on the Edge: How Europe can avoid another Crisis in Egypt," European Council on Foreign Relations, June 14, 2017. |

In 2017, Egypt's economy grew at a modest rate of just over 4%,21 and benchmarks for 2018 are trending positively.22 Since the flotation of the currency and the signing of a three-year, $12 billion IMF loan in November 2016, Egypt's macroeconomic picture has stabilized despite high consumer inflation that has engendered public discontent, but not unrest.23 The government has increased public salaries and pensions in an effort to ease austerity measures. Sectors such as energy, construction, and tourism grew steadily in 2017. In December 2017, an Egyptian and Italian partnership began commercial output from the Zohr natural gas field, the largest ever natural gas field discovered in the Mediterranean Sea.24 Over time, increased natural gas production is expected to reduce Egypt's dependence on imports.

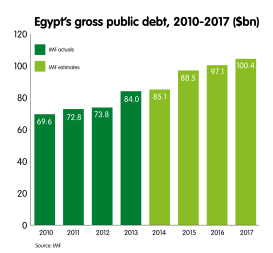

According to the Economist Intelligence Unit, tourism grew by 3.9% during Egypt's last fiscal year, compared to a 28.5% contraction the year before, and the resumption of direct Russian flights to Egypt is expected to further boost the hospitality sector.25 By late December 2017, Egypt's foreign exchange reserves had risen to $37 billion, a slightly higher return to its pre-2011 level. Over the long term, Egypt's fiscal picture remains a concern, though the IMF noted in January 2018 that Egypt had lowered its fiscal deficit. Overall, Egypt's gross debt is 91.3% of GDP, of which 74.6% is domestic and 16.7% is external.26

|

Figure 4. Egypt in the Next 20 Years National Intelligence Council's Projections |

|

|

Source: National Intelligence Council. "Global Trends: Paradox of Progress." January 2017. |

Current Issues

Terrorism and Islamist Militancy in Egypt

President Sisi, who led the 2013 military intervention and was elected president in mid-2014, came to power promising not only to defeat violent Salafi-Jihadi terrorist groups militarily, but also to counter their foundational ideology, which President Sisi and his supporters often attribute to the Muslim Brotherhood. President Sisi has outlawed the Muslim Brotherhood while launching a more general crackdown against a broad spectrum of opponents, both secular and Islamist. While Egypt is no longer beset by the kind of large-scale civil unrest and public protest it faced during the immediate post-Mubarak era, it continues to face terrorist and insurgent violence, both in the Sinai Peninsula and in the rest of Egypt.

Sinai Peninsula

Terrorists based in the Sinai Peninsula (the Sinai) have been waging an insurgency against the Egyptian government for more than six years. While the terrorist landscape in Egypt is evolving and encompasses several groups, a group called Sinai Province (SP) is known as the most lethal.27 Since its affiliation with the Islamic State in 2014, SP has attacked the Egyptian military continually, targeted Coptic Christian individuals and places of worship, and occasionally fired rockets into Israel. In October 2015, SP allegedly targeted Russian tourists departing the Sinai by planting a bomb aboard Metrojet Flight 9268, which exploded mid-air, killing all 224 passengers and crew aboard. Two years later, on November 24, 2017, SP gunmen launched an attack against the Al Rawdah mosque in the town of Bir al Abed in northern Sinai. That attack killed at least 305 people, making it the deadliest terrorist attack in Egypt's modern history.28

|

|

Source: http://www.mfo.org. |

Combating terrorism in the Sinai is particularly challenging due to an array of factors, including the following:

- Geography: The peninsula's interior is mountainous and sparsely populated, providing militants with ample freedom of movement.

- Demography and Culture: The Sinai's northern population is a mix of Palestinians and Bedouin Arab tribes whose relationship to the state is filled with distrust. Sinai Bedouin have faced discrimination and exclusion from full citizenship and from access to the economy. In the absence of development, a black market economy based primarily on smuggling has thrived, further contributing to the popular portrayal of Bedouin as outlaws. State authorities charge that the Sinai Bedouin seek autonomy from the central government, while residents insist on obtaining basic rights, such as property rights, full citizenship, and access to government services such as education and healthcare.29

- Economics: Bedouin claim that Egypt has underinvested in northern Sinai, channeling development toward southern tourist destinations which cater to foreign visitors. Northern Sinai consists of mostly flat desert terrain inhospitable to large-scale agriculture without significant investment in irrigation. For decades, the Egyptian state has claimed to follow successive Sinai development plans.30 However, Egyptian governance and development of the Sinai has been hampered by both public and private-sector corruption.

- Diplomacy: The 1979 Israeli-Egyptian peace treaty limits the number of soldiers that Egypt can deploy in the Sinai, subject to the parties' ability to negotiate changes as circumstances necessitate. Egypt and Israel mutually agree upon any short-term increase of Egypt's military presence in the Sinai. Since Israel returned control over the Sinai to Egypt in 1982, the area has been partially demilitarized, and the Sinai has served as an effective buffer zone between the two countries. The Multinational Force and Observers, or MFO, are deployed in the Sinai to monitor the terms of the Israeli-Egyptian peace treaty (see Figure 5).

In order to counter SP in northern Sinai, the Egyptian Armed Forces and police have declared a state of emergency, imposed curfews and travel restrictions, and erected police checkpoints along main roads. Authorities also have limited domestic and foreign media access to the northern Sinai, declaring it an active combat zone and unsafe for journalists.31 Reporters who contradict officials' statements about terrorist attacks face prosecution under a 2015 counterterrorism law.32 According to Jane's Defence Weekly, Egypt may be upgrading an old air base in the Sinai (Bir Gifgafa), where it could deploy Apache attack helicopters and unmanned aerial vehicles for use in counterterrorism operations.33 One recent news account suggests that Israel, with Egypt's approval, has used its own drones, helicopters, and aircraft to carry out more than 100 covert airstrikes inside Egypt against militant targets.34 As noted above, the terms of Egypt's peace treaty with Israel require Egypt to coordinate certain military deployments with Israel.

While an increased Egyptian military presence in the Sinai may be necessary to stabilize the area, observers have argued that military means alone are insufficient.35 These critics say that force should be accompanied by policies to reduce the appeal of antigovernment militancy by addressing local political and economic grievances. According to one account

Sinai residents are prohibited from joining any senior post in the state. They cannot work in the army, police, judiciary, or in diplomacy. Meanwhile, no development projects have been undertaken in North Sinai the past 40 years. The villages of Rafah and Sheikh Zuwayed have no schools or hospitals and no modern system to receive potable water. They depend on rainwater and wells, as if it were the Middle Ages.36

Beyond the Sinai: Other Egyptian Insurgent Groups

Outside of the Sinai, either in the western desert near the Libya border or other areas (Cairo, Nile Delta, Upper Egypt), small nationalist insurgent groups, such as Liwa al Thawra (The Revolution Brigade) and Harakat Sawaed Misr (Arms of Egypt Movement, referred to by its Arabic acronym HASM), have carried out high-level assassinations of military/police officials and bombings of economic infrastructure. According to one expert, these insurgent groups are comprised mainly of former Muslim Brotherhood activists who have splintered off from the main organization to wage an insurgency against the government.37

On January 31, 2018, the U.S. State Department designated Liwa al Thawra and HASM as Specially Designated Global Terrorists (SDGTs) under Section 1(b) of Executive Order (E.O.) 13224.38 The State Department noted that some of the leaders of both groups "were previously associated with the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood."

Egypt and Hamas

In 2017, Egypt resumed previous attempts at forging greater Palestinian unity between Hamas (which controls the Gaza Strip) and Fatah (which controls the West Bank via the Palestinian Authority, or PA). Egypt sponsored Palestinian reconciliation talks and has backed a greater role in Gaza for former Fatah security chief Muhammad Dahlan.39

In late 2017, the leading Palestinian factions took tentative steps toward more unified rule. In October, after days of negotiations in Cairo facilitated by then-head of Egyptian General Intelligence Khaled Fawzy, Hamas and the Fatah-led PA reached an agreement for the PA to assume greater administrative control over Gaza. The PA gained at least nominal control of Gaza's border crossings with Israel and Egypt in November, though it is unclear if a larger handover of control will take place, or whether the unity agreement—like similar agreements since 2007—will remain unimplemented.40

Egypt's new approach toward Gaza appears to have had some limited success. According to one report, "as Egypt opened the border with Gaza more frequently this summer [2017], Hamas provided information to Egypt about Islamist militants who were fighting alongside the Islamic State in Sinai."41 As Hamas has engaged the Palestinian Authority in unity talks under Egyptian auspices, its relationship with Sinai-based terrorist groups such as SP has become adversarial. In January 2018, SP released a video calling on its supporters to attack Hamas.42

Concerns over Human Rights Violations

President Sisi has come under repeated international criticism for an ongoing government crackdown against various forms of political dissent and freedom of expression. Certain practices of Sisi's government, the parliament, and the security apparatus have been contentious, including the following:

- the use of mass trials to prosecute political activists on criminal charges, without individual due process;

- the passage of an antiprotest law that infringes upon peaceful assembly;

- police brutality, the apparently deliberate use of torture by security forces, and reported enforced disappearances of political opponents;

- the use of criminal prosecutions, travel bans, and asset freezes against human rights defenders; and

- the passage of Law 70 of 2017 on Associations and Other Foundations, which institutes restrictions on Egyptian nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and makes violations subject to criminal prosecution.

According to the State Department, "the most significant human rights problems [in 2016] were excessive use of force by security forces, deficiencies in due process, and the suppression of civil liberties."43 Extrajudicial killings by police forces are alleged to have increased in 2017.44

The NGO Law

In May 2017, President Sisi signed Law 70 of 2017 on Associations and Other Foundations Working in the Field of Civil Work into law. The Parliament had passed this bill six months earlier, and both the passage and signing drew widespread international condemnation. The new law (which replaced a 2002 NGO law) requires NGOs to receive prior approval from internal security before accepting foreign funding. It also restricts the scope of permitted NGO activities and increases penalties for violations, including possible imprisonment for up to five years. In June 2017, Secretary of State Rex Tillerson told lawmakers that "We were extremely disappointed by the recent legislation that President Sisi signed regarding NGO registration and preventing certain NGOs from operating. We're in discussions with them about how that is harmful to the way forward."45

Some uncertainty remains over the status of the law's implementation. After a visit to the United States by a group of Egyptian lawmakers in fall 2017, one parliamentarian remarked that, "As we know, the executive regulations of the new NGO law—which was passed by parliament in November 2016—have not yet been issued and so the law has not gone into implementation."46 In some cases, plaintiffs have successfully litigated against the state at the Supreme Constitutional Court, raising the possibility that those in opposition to perceived repressive new Egyptian legislation, such as the NGO law, could file suit.47 The provisions in the law nonetheless are likely to have a chilling effect on civil society activism in Egypt, as do the still-active criminal charges imposed against U.S. and Egyptian employees of several U.S.-based democracy-promotion organizations (see below).

Crackdown on the LGBT Community

In September 2017, several audience members at a musical performance in Cairo raised rainbow flags, a symbol of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender or LGBT pride. Images of the flags spread on social media, leading Egyptian government officials and religious figures to publicly condemn homosexuality as a threat to Egyptian society.48 In the days and weeks following the concert, dozens of Egyptians were arrested. In November 2017, a court in Cairo found 14 individuals guilty of "inciting debauchery" and "abnormal sexual relations." Under current Egyptian law, openly identifying as homosexual is not explicitly a crime, though state prosecutors have used a 1961 prostitution law (prostitution law number 10 of 1961) to charge people suspected of engaging in consensual homosexual conduct with "habitual debauchery."49 A 2014 report by the Law Library of Congress notes that under Egypt's penal code, homosexuality is punished as a "scandalous act," with detention for up to one year and/or a fine of up to 300 EGP (about US$43).50

Some Egyptian lawmakers have proposed legislation to criminalize same-sex sexual activity. According to Amnesty International, a proposed bill would "define homosexuality for the first time and sets harsher penalties of up to five years imprisonment—or even up to 15 years if a person is convicted on multiple charges under different provisions of the law.... If passed, this law would further entrench stigma and abuse against people based on their perceived sexual orientation."51 In November 2017, Minority Leader of the United States House of Representatives Nancy Pelosi wrote a letter to Egyptian Speaker of the House Ali Abdel Aal Sayyed Ahmed calling on him to "denounce the ongoing assault on civil liberties in Egypt, and in particular condemn this law and these attacks on the LGBT community. We call on you to facilitate the release of the innocent LGBT men, women and allies who still languish in jail."52

Coptic Christian Rights and the Law on Church Construction

For years, the minority Coptic Christian community in Egypt has called for equal treatment under the law, asserting that its adherents face professional and social discrimination while the community as a whole is subject to occasional sectarian attacks by citizen vigilantes and terrorist groups. An additional area of concern for Coptic Christians has been state regulation of Coptic Church construction. Coptic Christians have long demanded that the government reform long-standing laws (some dating back to 1856 and 1934 respectively) on building codes for Christian places of worship, which many contend are overly restrictive.

Article 235 of Egypt's 2014 constitution mandates that parliament reform these building code regulations. In 2016, Parliament approved a new church construction law (Law 80 of 2016), that expedited the government approval process for the construction and restoration of Coptic churches, among other structures. Although Coptic Pope Tawadros II welcomed the law,53 others claim that it continues to be discriminatory. According to Human Rights Watch, "The new law allows governors to deny church-building permits with no stated way to appeal, requires that churches be built 'commensurate with' the number of Christians in the area, and contains security provisions that risk subjecting decisions on whether to allow church construction to the whims of violent mobs."54

Egypt and Russia

Egypt and Russia, close allies in early years of the Cold War, have again strengthened bilateral ties. This development is due in large part to the rise of President Sisi, who has promised to restore Egyptian stability and international prestige. His relationship with Russian President Vladimir Putin has rekindled, in the words of one observer, "a romanticized memory of relations with Russia during the Nasser era."55

|

Egypt and the Soviet Union During the Cold War From the mid-1950s until the late 1970s, Egypt maintained close relations with the former Soviet Union. In the early years of the Cold War, Egypt found itself at the center of superpower competition for influence in the Middle East. Wary of taking sides, Egypt's second President Gamal Abdel Nasser managed, for a short period, to steer Egypt clear of either the Soviet or Western "camp" and was instrumental in helping to establish the nonaligned movement. U.S.-Egyptian relations soured when Nasser turned to the Soviets and the Czechs in 1955 for military training and equipment after the West, frustrated by Nasser's repeated rejections and his support of Algerian independence against the French, refused to provide Egypt with defense assistance. After Nasser's death in 1970, Vice President Anwar Sadat became president of Egypt. At the time, Egypt was humiliated by its defeat in the June 1967 War and the accompanying loss of the Sinai Peninsula to Israel. Under these circumstances, Sadat calculated that a military victory was needed to boost his own legitimacy and improve Egypt's position in any future negotiations with Israel. He sought Soviet support, but was refused and, in July 1972, Sadat expelled Soviet military advisors from Egypt. The October 1973 War, which initially took Israel by surprise, was costly for both sides, but succeeded in boosting Sadat's credibility with the Egyptian people, enabling him to embark on a path which would ultimately sever Egypt's ties to the Soviet Union and bring it closer to the West. |

Egypt and Russia have improved ties in a number of ways including an increase in arms deals. Russian and Egyptian press reports in 2016 suggested that the two governments reached a contract to upgrade Egypt's aging fleet of legacy Soviet MiG-21 aircraft to a fourth generation MiG-29M variant.56 In December 2015, news sources reported that Russia would provide 46 standard Ka-52 helicopters to Egypt for its air force. Subsequent reports also suggest that Egypt may purchase the naval version for use on its two French-procured Mistral-class helicopter dock vessels.57 Egypt also has reportedly purchased the S-300VM surface-to-air missile defense system from Russia.58

Egypt and Russia also reportedly have expanded their cooperation on nuclear energy. In 2015, Egypt reached a deal with Russian-state energy firm Rosatom to construct a 4,800-megawatt nuclear power plant in the Egyptian Mediterranean coast town of Daba'a, 80 miles northwest of Cairo. Russia is lending Egypt $25 billion over 35 years to finance the construction and operation of the nuclear power plant. The plant aims to be operational by 2022 and produce electricity by 2024.

As Egyptian and Russian foreign policies have become more closely aligned in conflict zones such as eastern Libya, bilateral military cooperation has expanded. One report suggests that Russian Special Forces based out of an airbase in Egypt's western desert (Sidi Barrani) may be aiding Qadhafi-era retired General Khalifa Haftar, who also has been supported by Egypt and now controls significant territory in eastern Libya.59 Although Egyptian officials had initially denied any Russian presence on their soil, in November 2017, both sides signed a draft agreement governing the use of each other's air space.60

Trump Administration Policy toward Egypt

President Trump has sought to improve U.S. relations with Egypt, which were perceived as strained under President Obama.61 Overall, President Trump has emphasized the importance of partnering with Arab leaders seen by many observers as autocratic in order to combat transnational terrorism, contain Iran, and pave the way for resuming Israeli-Palestinian peace negotiations. As part of the Administration's de-emphasis on pressing its partners for democratic reforms, President Trump stated in a May 2017 speech that "We are adopting a principled realism, rooted in common values and shared interests.... Our partnerships will advance security through stability, not through radical disruption."62 Nevertheless, Administration officials have raised concerns about Egypt's new NGO law (see above) and the continued detention of American citizens in Egypt (see below).

One discernable difference between the Trump and Obama Administrations has been the frequency of U.S.-Egyptian high-level dialogue. In 2017, Presidents Trump and Sisi interacted frequently, personally meeting three times and conducting five official phone calls.63 According to official readouts of their meetings, both sides focused on an array of bilateral issues, including Egypt's role in facilitating Palestinian reconciliation, the continuation of U.S. foreign assistance to Egypt, and the possible expansion of U.S.-Egyptian trade and investment.

In early 2017, the United States signaled a willingness to resume U.S. participation in Exercise Bright Star, a biennial multinational military training exercise cohosted by the United States and Egypt that helps foster the interoperability of U.S. and Egyptian forces and provides specialized training opportunities for CENTCOM in the Middle East.64 In February 2017, General Joseph L. Votel, Commander of the United States Central Command, remarked that "It is my goal to get that exercise back on track and try to re-establish that as another key part of our military relationship."65 In September 2017, an estimated 200 U.S. soldiers participated in Bright Star 17 at Mohamed Naguib Military Base in Egypt, where U.S. and Egyptian forces conducted battle simulations involving U.S.-origin major defense equipment, such as Egyptian F-16s and M1A1 Egyptian tanks.66 This marked the first time since October 2009 that the United States participated in Exercise Bright Star. In 2011, Bright Star was cancelled following the "Arab Spring" uprising. In 2013, a day after the Egyptian military and police launched a crackdown against the Muslim Brotherhood, President Obama suspended U.S. participation in Bright Star.

The detention of American citizens in Egypt has continued to be an issue in U.S.-Egyptian relations under the Trump Administration. In April 2017, Egypt released detained Egyptian-American aid worker Aya Hijazi, who, along with her husband, had been imprisoned pretrial for nearly three years. After she returned to the United States, President Trump hosted Ms. Hijazi in a ceremony at the Oval Office. He later claimed that the government of Egypt had complied with his request for her release, asserting that he succeeded where the former Administration had failed.67

On January 20, 2018, Vice President Michael Pence traveled to Egypt and met with President Sisi to discuss various issues in bilateral relations, including Egypt's detention of two American citizens.68 According to the Vice President, "I raised specifically the situation for two Americans who are currently being held, imprisoned here in Egypt—Ahmed Etwiy and Mustafa Kassem—who have been imprisoned here since 2013. And President Al Sisi assured me that he would give that very serious attention in both cases."69

Recent Developments in U.S. Aid to Egypt

During summer 2017, the Trump Administration took various steps toward reducing U.S. foreign military and economic assistance to Egypt, reportedly out of U.S. concern over Egypt's new legal restrictions on nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and its reported ties to the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK, or North Korea). On July 5, 2017, President Trump called President Sisi and, according to a White House readout, "discussed the threat from North Korea," with President Trump stressing "the need for all countries to fully implement U.N. Security Council resolutions on North Korea, stop hosting North Korean guest workers, and stop providing economic or military benefits to North Korea."70 The President's focus on Egyptian-North Korean cooperation could relate to allegations that Egypt may have violated various United Nations-imposed sanctions on trade with North Korea as well as a prohibition on arms transactions with North Korea.71

On August 22, 2017, various news sources reported that the Trump Administration, having felt (in the words of one unnamed official) "blindsided" by President Sisi's approval of the new NGO law, planned to take several actions regarding U.S. foreign assistance to Egypt.72 Various outlets characterized these actions as a delay or diversion of up to $300 million in U.S. foreign assistance. The following is a summary of the Administration's actions.

- Waiver Issued. In August, Secretary of State Rex Tillerson issued the national security waiver contained in Section 7041(a)(3)(B) of P.L. 114-113, the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2016. This waiver allows $195 million in withheld FY2016 Foreign Military Financing (FMF) funds (out of a total of $1.3 billion appropriated) to be obligated without the Secretary having to certify whether the government of Egypt is taking several steps to advance democracy and human rights. The United States and Egypt may now use these funds (which would have expired October 1, 2017) to sustain prior purchases of major U.S. defense equipment, though according to the State Department, rather than being immediately available for Egypt, the $195 million will be held in reserve until the Administration sees progress on democracy in Egypt. An Associated Press story notes that when the Secretary of State issued the waiver on August 22, he also submitted a congressionally mandated report to the appropriations committees detailing the justification for the waiver, including how Egypt is failing to protect free speech, investigate abuses by its security forces, or grant U.S. monitors access to the Sinai Peninsula.73 The State Department has declined requests from human rights groups to make the report public.

- Intention to repurpose $65.7 million in FY2017 FMF. The Administration also plans to redirect $65.7 million in FMF for Egypt elsewhere. This action is tied to an informal hold placed on FY2014 FMF by Senator Patrick Leahy over his reported objections to the Egyptian government's human rights conduct and its use of U.S.-supplied military equipment in counterterrorism operations in the Sinai.74 Since the State Department has determined that FY2014 FMF to Egypt can no longer be repurposed, it reportedly intends to redirect $65.7 million in FY2017 FMF for Egypt.

- Obligating $155.635 million in Economic Aid. On August 23, 2017, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) notified Congress of its intent to obligate a total of $155.635 million in Economic Support Fund (ESF) aid for Egypt. This obligation is comprised of ESF funds from various fiscal years, of which $111.75 million would come from FY2016 Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO) funds. In FY2016, Congress appropriated "up to" $150 million in FY2016 ESF for Egypt, though it appears that the Administration has indicated that it will not obligate the full $150 million for FY2016. One report suggests that USAID may reprogram $20 million in FY2016 ESF for Egypt to support water programs in the West Bank.75

On January 23, 2018, the Administration notified Congress of its intent to obligate $1.039 billion in FY2017 FMF out of a total of $1.3 billion appropriated for FY2017. The $260.7 million difference between the appropriated and obligated FMF figures is composed of

- $195 million in FY2017 FMF that has been withheld pending a certification and reporting as specified in Section 7041 (a)3(A) of P.L. 115-31, the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2017; and

- A $65.7 million reduction in FY2017 FMF, which the Administration had announced in summer 2017. According to the State Department, "This decision was made in support of our national security interests as a result of Egyptian inaction on a number of critical requests by the United States, including Egypt's ongoing relationship with the Democratic People's Republic of Korea, lack of progress on the 2013 convictions of U.S. and Egyptian nongovernmental organization (NGO) workers, and the enactment of a restrictive NGO law that will likely complicate ongoing and future U.S. assistance to the country. The Department of State will notify the committees of how the Department intends to utilize the $65,700,000 in FY 2017 FMF-OCO at a later date."76

FY2018 U.S. Foreign Assistance to Egypt

For FY2018, the President is requesting a total of $1.38 billion in foreign assistance for Egypt, nearly all of which would come from the FMF account. The $75 million FY2018 Economic Support and Development Fund (ESDF) request for Egypt is well below prior year appropriations, and Egypt has not received less than $100 million in U.S. economic assistance since the late 1970s.

|

|

FY2014 |

FY2015 |

FY2016 |

FY2017 EST |

FY2018 Req. |

|

FMF |

$1,300.00 |

$1,300.00 |

$1,300.00 |

$1,300.00 |

$1,300.00 |

|

ESF |

$200.00 |

$150.00 |

$150.00 |

$112.50 |

$75.00 |

|

NADR |

— |

$3.10 |

$2.50 |

$3.00 |

$2.50 |

|

INCLE |

$3.00 |

$1.00 |

$2.00 |

$2.00 |

$2.00 |

|

IMET |

— |

$1.70 |

$1.80 |

$1.80 |

$1.80 |

|

Other |

$3.00 |

$5.80 |

$6.30 |

$6.80 |

$6.30 |

|

Total |

$1,503.00 |

$1,454.10 |

$1,454.50 |

$1,419.30 |

$1,381.30 |

Will President Trump Restore Cash Flow Financing to Egypt?

As Congress considers FY2018 assistance to Egypt, one question is whether the Trump Administration is prepared to reverse or otherwise modify the 2015 Obama Administration decision to phase out cash flow financing and limit the use of FMF to only counterterrorism, border security, Sinai Peninsula security, and maritime security programs.77 Successive Administrations have used cash flow financing to permit Egypt to set aside almost all FMF funds for current year payments only, rather than set aside the full amount needed to meet the full cost of multiyear purchases.78 During the 2015-2018 phaseout of cash flow financing, Egypt has made several purchases of major defense equipment from non-U.S. suppliers, including Russia (see above) and France.79

Prior to President Sisi's visit to the United States in spring 2017, there had been some speculation that the Trump Administration could reverse the previous Administration's phaseout of cash flow financing. According to one senior White House official in March 2017, "We'll discuss with Egypt whether cash-flow financing is something they need or not, but it is also something that would be a process of our internal budget discussions that are ongoing. So we can't really get ahead of the budget planning now."80 Several months later, during a June 2017 hearing before the House Foreign Affairs Subcommittee on Terrorism, Nonproliferation and Trade, Vice Admiral Joseph Rixey, the Director of the Defense Security Cooperation Agency, noted that cash flow financing authority for Egypt had been phased out by the previous administration. He added, "that was removed. Now we will not execute a [foreign military sale] case until the cash is there....That policy is still in place."81

While critics of Egypt's human rights record have opposed a reinstatement of cash flow financing to Egypt, others have suggested that it could be restored under certain conditions.82 According to David Schenker, an expert on Arab politics at The Washington Institute and reportedly a potential nominee for Assistant secretary of State for Near Eastern affairs, "Washington could reinstitute cash flow financing, which was scrapped in 2015 after the military coup, but only for equipment that the U.S. Department of Defense deems related to counterterrorism and border security operations."83 Under cash-flow financing arrangements, Foreign Military Sales (FMS) cases for Egypt were undertaken before being fully funded in anticipation of additional appropriations in future years. P.L. 115-31 requires the Secretary of State to report to the committees on appropriations on any plan to restructure U.S. military assistance for Egypt, including a description of any planned modifications regarding the procurement of military equipment.

Congressional Action on Egypt

Lawmakers may continue to influence the nature of the evolving U.S.-Egyptian bilateral relationship either through the appropriations process or through regular congressional oversight.

Egypt's poor human rights record has sparked regular criticism from U.S. officials and some Members of Congress. During a 2017 Senate Appropriations Subcommittee on State, Foreign Operations and Related Programs hearing on U.S. assistance to Egypt, Subcommittee Chairman Senator Lindsey Graham remarked, "I really worry about a consolidation of power that is basically undemocratic."84 During that same hearing, other witnesses were critical not only of Egypt's human rights record, but of the totality of U.S.-Egyptian relationship.85

Since FY2012, Members have passed appropriations legislation that withholds the obligation of Foreign Military Financing (FMF) to Egypt until the Secretary of State certifies that Egypt is taking various steps toward supporting democracy and human rights. In the 115th Congress, S. 1780, the Department of State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs Appropriations Act, 2018, would allocate up to $1 billion in FY2018 FMF for Egypt, while stipulating that 25% of that amount (as opposed to 15% in previous annual appropriations legislation) shall be withheld until the Secretary of State certifies and reports to the Committees on Appropriations that the Government of Egypt is taking effective steps to advance democracy and human rights in Egypt. A waiver for this certification is included in the bill. H.R. 3362, the House version of the Department of State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs Appropriations Act, 2018, would provide $1.3 billion in FMF to Egypt. It would also permit FMF to be transferred to an interest-bearing account in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. The bill does not include a withholding of FMF or certification requirement, but it requires the Secretary of State to consult with appropriators "on any plan to restructure military assistance for Egypt."

|

Congressionally Mandated Certifications on FMF to Egypt In FY2012, appropriators began inserting language into annual omnibus appropriations acts that withholds the obligation of Foreign Military Financing to Egypt until the Secretary of State can certify that Egypt is taking various steps toward supporting a democratic transition to civilian government. With the exception of FY2014, lawmakers have included a national security waiver to allow the Administration to waive these congressionally mandated certification requirements under certain conditions. P.L. 115-31, the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2017, required that 15% of FMF funds be withheld from obligation until the Secretary of State can certify to the appropriations committees that Egypt is taking effective steps to advance democracy and human rights, among other things. This certification requirement does not apply to FMF used for counterterrorism, border security, and nonproliferation programs for Egypt. The Secretary of State may waive the certification requirement if he/she reports to Congress that to do so is important to the national security interest of the United States. |

|

Fiscal Year |

Public Law |

Conditions Requiring Secretary of State Certification |

National Security Waiver for Certification |

Date of Waiver Exercised by Secretary of State |

|

FY2012 |

Section 7041(a)(1)(B) |

Section 7041(a)(1)(C) |

March 23, 2012 |

|

|

FY2013 |

(continuing resolution applied conditions in FY2012 Act) |

(continuing resolution applied conditions in FY2012 Act) |

May 2013 |

|

|

FY2014 |

Section 7041(a)(6)(A)(B) |

None |

— |

|

|

FY2015 |

Section 7041(a)(6)(A) |

Section 7041(a)(6)(C) |

May 12, 2015 |

|

|

FY2016 |

Section 7041(a)(3)(A) |

Section 7041(a)(3)(B) |

August 2017 |

|

|

FY2017 |

Section 7041(a)(3)(A) |

Section 7041(a)(3)(B) |

TBD |

Notes: Conditions on the obligation of FMF to Egypt in Omnibus Appropriations Acts differ year to year.

H.R. 3219, the Make America Secure Appropriations Act, 2018 (passed in the House on July 27, 2017), would make Defense Department appropriations available from the "Counter-Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant Train and Equip Fund" to Egypt for border security to counter the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant and their affiliated or associated groups.

Other Proposed Legislation in the 115th Congress

H.Res. 113—Among other things, calls for the President to reinstate cash flow financing (CFF) to Egypt in 2018, and afterward.

H.Res. 673—Among other things, urges the Government of Egypt to "enact serious and legitimate reforms to ensure Coptic Christians are given the same rights and opportunities as all other Egyptian citizens."

S.Res. 108—Among other things, urges the President of the United States and the Secretary of State to "engage the Egyptian Government on new ways to advance the bilateral relationship economically, militarily, diplomatically, and through cultural exchanges, while ensuring respect for the universal rights of the Egyptian people."

S. 68 (H.R. 377 in the House)—The Muslim Brotherhood Terrorist Designation Act of 2017 would require, not later than 60 days after the date of the enactment, that the Secretary of State, in consultation with the intelligence community, submit a detailed report to Congress indicating whether the Muslim Brotherhood meets the criteria for designation as a foreign terrorist organization under Section 219(a) of the Immigration and Nationality Act (8 U.S.C. 1189(a)). If the Secretary of State determines that the Muslim Brotherhood does not meet the criteria, the bill requires a detailed justification as to which criteria have not been met.

S. 266 (H.R. 754 in the House)—The bill requires that the Speaker of the House of Representatives and the President pro tempore of the Senate make appropriate arrangements for the posthumous award, on behalf of Congress, of a gold medal of appropriate design to Anwar Sadat in recognition of his achievements and heroic actions to attain comprehensive peace in the Middle East.

U.S.-Egyptian Relations Going Forward

As the Trump Administration begins its second year in office, U.S. relations with Egypt seem poised to move beyond an introductory posture and toward routine engagement focused on a broad set of issues, such as the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and counterterrorism. Barring any major developments in the Israeli-Palestinian arena, the current relationship lacks any signature project that binds the United States and Egypt together. Moreover, as President Sisi continues his consolidation of power and as the economy slowly recovers, Egypt seems to be continuing to pursue a more independent foreign policy that seeks to balance its relationships with great power states, Western Europe, and the Arab Gulf monarchies. Some Egyptians have even speculated about relations with the United States being based less on shared interests and more on transactional considerations.86

For U.S. policymakers and Members of Congress, Egypt may not be the Middle East region's top priority when compared to thwarting Iran and dealing with crises such as the conflict in Syria. Nevertheless, there are potential flashpoints worth considering. Terrorism within Egypt may continue, and it is unclear whether the Egyptian government is willing to work more closely with the U.S. military and adjust its counterterrorism doctrine to more effectively confront nonstate actors such as SP. Egypt also is embroiled in regional disputes with Nile Basin countries, such as Ethiopia, which is nearing completion on the $4.2 billion Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam, a major hydroelectric project which Egypt believes will cut its share of the Nile once the dam is filled. In Gaza, while Egypt has played a positive role, further reconciliation between Hamas and the Palestinian Authority is stalled. Should another Israel-Hamas confrontation occur, Egypt would invariably be looked to as mediator.

Appendix. Background on U.S. Foreign Assistance to Egypt

Overview

Between 1946 and 2016, the United States provided Egypt with $78.3 billion in bilateral foreign aid (calculated in historical dollars—not adjusted for inflation).87 The 1979 Peace Treaty between Israel and Egypt ushered in the current era of U.S. financial support for peace between Israel and its Arab neighbors. In two separate memoranda accompanying the treaty, the United States outlined commitments to Israel and Egypt, respectively. In its letter to Israel, the Carter Administration pledged to "endeavor to take into account and will endeavor to be responsive to military and economic assistance requirements of Israel." In his letter to Egypt, former U.S. Secretary of Defense Harold Brown wrote the following:

In the context of the peace treaty between Egypt and Israel, the United States is prepared to enter into an expanded security relationship with Egypt with regard to the sales of military equipment and services and the financing of, at least a portion of those sales, subject to such Congressional review and approvals as may be required.88

All U.S. foreign aid to Egypt (or any foreign recipient) is appropriated and authorized by Congress. The 1979 Egypt-Israel Peace Treaty is a bilateral peace agreement between Egypt and Israel, and the United States is not a legal party to the treaty. The treaty itself does not include any U.S. aid obligations, and any assistance commitments to Israel and Egypt that could be potentially construed in conjunction with the treaty were through ancillary documents or other communications and were—by their terms—subject to congressional approval (see above). However, as the peace broker between Israel and Egypt, the United States has traditionally provided foreign aid to both countries to ensure a regional balance of power and sustain security cooperation with both countries.

In some cases, an Administration may sign a bilateral "Memorandum of Understanding" (MOU) with a foreign country pledging a specific amount of foreign aid to be provided over a selected time period subject to the approval of Congress. In the Middle East, the United States has signed foreign assistance MOUs with Israel and Jordan. Currently, there is no U.S.-Egyptian MOU specifying a specific amount of total U.S. aid pledged to Egypt over a certain time period.89

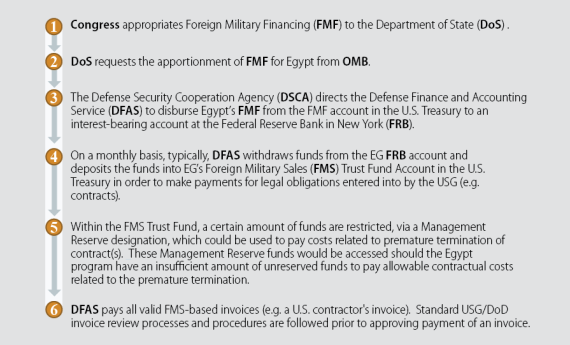

Congress typically specifies a precise allocation of most foreign assistance for Egypt in the foreign operations appropriations bill. Egypt receives the bulk of foreign aid funds from three primary accounts: Foreign Military Financing (FMF), Economic Support Funds (ESF), and International Military Education and Training (IMET).90 The United States offers IMET training to Egyptian officers in order to facilitate U.S.-Egyptian military cooperation over the long term.

Military Aid and Arms Sales

Overview

Since the 1979 Israeli-Egyptian Peace Treaty, the United States has provided Egypt with large amounts of military assistance. U.S. policymakers have routinely justified this aid to Egypt as an investment in regional stability, built primarily on long-running military cooperation and on sustaining the treaty—principles that are supposed to be mutually reinforcing. Egypt has used U.S. military aid through the FMF to (among other things) purchase major U.S. defense systems, such as the F-16 fighter aircraft, the M1A1 Abrams battle tank, and the AH-64 Apache attack helicopter.

|

Frequently Asked Question: Is U.S. Military Aid Provided to Egypt as a Cash Transfer? No. All U.S. military aid to Egypt finances the procurement of weapons systems and services from U.S. defense contractors.91 The United States provides military assistance to U.S. partners and allies to help them acquire U.S. military equipment and training. Egypt is one of the main recipients of FMF, a program with a corresponding appropriations account administered by the Department of State but implemented by the Department of Defense. FMF is a grant program that enables governments to receive equipment and associated training from the U.S. government or to access equipment directly through U.S. commercial channels. Most countries receiving FMF generally purchase goods and services through government-to-government contracts, also known as Foreign Military Sales (FMS). According to the Government Accountability Office, "under this procurement channel, the U.S. government buys the desired item on behalf of the foreign country (Egypt), generally employing the same criteria as if the item were being procured for the U.S. military." The vast majority of what Egypt purchases from the United States is conducted through the FMS program funded by FMF. Egypt uses few of its own national funds for U.S. military equipment purchases. Under Section 36(b) of the Arms Export Control Act (AECA), Congress must be formally notified 30 calendar days before the Administration can take the final steps of a government-to-government foreign military sale of major U.S.-origin defense equipment valued at $14 million or more, defense articles or services valued at $50 million or more, or design and construction services valued at $200 million or more. In practice, prenotifications to congressional committees of jurisdiction occur and proposed arms sales generally do not proceed to the public official notification stage until issues of potential concern to key committees have been resolved. |

Realigning Military Aid from Conventional to Counterterrorism Equipment

For decades, FMF grants have supported Egypt's purchases of large-scale conventional military equipment from U.S. suppliers. However, as mentioned above, the Obama Administration announced that future FMF grants may only be used to purchase equipment specifically for "counterterrorism, border security, Sinai security, and maritime security" (and for sustainment of weapons systems already in Egypt's arsenal).92

It is not yet clear how the Trump Administration will determine which U.S.-supplied military equipment would help the Egyptian military counter terrorism and secure its land and maritime borders. Overall, some defense experts continue to view the Egyptian military as inadequately prepared, both doctrinally and tactically, to face the threat posed by terrorist/insurgent groups such as Sinai Province. According to a former U.S. National Security Council official, "They [the Egyptian military] understand they have got a problem in Sinai, but they have been unprepared to invest in the capabilities to deal with it."93 To reorient the military toward unconventional warfare, the Egyptian military needs, according to one assessment, "heavy investment into rapid reaction forces equipped with sophisticated infantry weapons, optics and communication gear ... backed by enhanced intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance platforms. In order to transport them, Egypt would also need numerous modern aviation assets."94

Special Military Assistance Benefits for Egypt

In addition to substantial amounts of annual U.S. military assistance, Egypt has benefited from certain aid provisions that have been available to only a few other countries. For example:

- Early Disbursal and Interest-Bearing Account: Between FY2001 and FY2011, Congress granted Egypt early disbursement of FMF funds (within 30 days of the enactment of appropriations legislation) to an interest-bearing account at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.95 Interest accrued from the rapid disbursement of aid has allowed Egypt to receive additional funding for the purchase of U.S.-origin equipment. In FY2012, Congress began to condition the obligation of FMF, requiring the Administration to certify certain conditions had been met before releasing FMF funds, thereby eliminating their automatic early disbursal. However, Congress has permitted Egypt to continue to earn interest on FMF funds already deposited in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

- The Excess Defense Articles (EDA) program provides one means by which the United States can advance foreign policy objectives—assisting friendly and allied nations through provision of equipment in excess of the requirements of its own defense forces. The Defense Security Cooperation Agency (DSCA) manages the EDA program, which enables the United States to reduce its inventory of outdated equipment by providing friendly countries with necessary supplies at either reduced rates or no charge. As a designated "major non-NATO ally," Egypt is eligible to receive EDA under Section 516 of the Foreign Assistance Act and Section 23(a) of the Arms Export Control Act.

|

|

Source: Information from Defense Security Cooperation Agency. Graphic created by CRS. |

Economic Aid

Overview

Over the past two decades, U.S. economic aid to Egypt has been reduced by over 90%, from $833 million in FY1998 to a request of $75 million for FY2018. The $75 million FY2018 request for Egypt is well below prior year appropriations, and Egypt has not received less than $100 million in U.S. economic assistance since the late 1970s.

Beginning in the mid to late 1990s, as Egypt moved from an impoverished country to a lower-middle-income economy, the United States and Egypt began to rethink the assistance relationship, emphasizing "trade not aid." Congress began to scale back economic aid both to Egypt and Israel due to a 10-year agreement reached between the United States and Israel in the late 1990s known as the "Glide Path Agreement, which gradually reduced U.S. economic aid to Egypt to $400 million by 2008."96 U.S. economic aid to Egypt stood at $200 million per year by the end of the George W. Bush Administration, whose relations with then-President Hosni Mubarak suffered over the latter's reaction to the Administration's democracy agenda in the Arab world.97

During the final years of the Obama Administration, distrust of U.S. democracy promotion assistance led the Egyptian government to obstruct many U.S.-funded economic assistance programs. According to the Government Accountability Office (GAO), the Department of State and the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) reported hundreds of millions of dollars ($460 million as of 2015) in unobligated prior year ESF funding.98 As these unobligated balances grew, it created pressure on the Obama Administration to reobligate ESF funds for other purposes. In 2016, the Obama Administration notified Congress that it was reprogramming $108 million of ESF that had been appropriated for Egypt in FY2015 but remained unobligated for other purposes. The Administration claimed that its actions were due to "continued government of Egypt process delays that have impeded the effective implementation of several programs."99 As mentioned above, in 2017, the Trump Administration also reprogrammed approximately $20 million in FY2016 ESF for Egypt to support water programs in the West Bank.

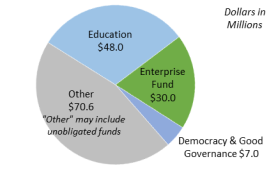

U.S. economic aid to Egypt is divided into two components: (1) USAID-managed programs (public health, education, economic development, democracy and governance); and (2) the U.S.-Egyptian Enterprise Fund. Both are funded primarily through the Economic Support Fund (ESF) appropriations account.

USAID Programs in Egypt

|

|

Source: USAID, August 2017. |

For FY2017, USAID estimates that of the $155.6 million in ESF it has obligated for Egypt, an estimated $7 million will be directed toward democracy, good governance, human rights, and political competition; $48 million for basic and higher education; $30 million for the Egyptian-American Enterprise Fund (EAEF); and the remaining funds for various economic development, trade, macroeconomic growth, agriculture, private sector competitiveness, and water programs.100 Aside from the EAEF, USAID's Higher Education Initiative (HEI) has received the most programmatic ESF assistance from USAID for Egypt since 2011.

U.S. Funding for Democracy Promotion

U.S. funding for democracy promotion activities and good governance has been a source of acrimony between the United States and Egypt for years. Though the two governments have held numerous consultations over the years regarding what Cairo might view as acceptable U.S.-funded activities in the democracy and governance sector, it appears that the sides have not reached a consensus. Using the appropriations process, Congress has acted to ensure that "democracy and governance activities shall not be subject to the prior approval by the government of any foreign country."

Democracy assistance implementers face severe barriers to operating openly in Egypt. In 2013, an Egyptian court convicted and sentenced 43 people, including employees of the National Democratic Institute (NDI) and the International Republican Institute (IRI), for allegedly spending money on behalf of organizations that were operating in Egypt without a license. In response, in annual aid appropriations measures, Congress has placed conditions on U.S. economic assistance. Most recently, Section 7041(a)(2)(B) of P.L. 115-31, the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2017, mandates that the Secretary of State withhold an amount of Economic Support Fund (ESF) to Egypt determined to be equivalent to that expended by the United States Government for bail, and by nongovernmental organizations for legal and court fees associated with democracy-related trials in Egypt until the Secretary certifies that Egypt has dismissed the convictions issued by the Cairo Criminal Court on June 4, 2013.

To the extent that USAID continues to fund democracy and governance programs for Egypt, most programs fund Egyptian government activities rather than those of civil society. The agency notified Congress in August 2017 that it intends to support the following programs with FY2016 ESF (OCO) and Democracy Fund funds:101

- $1.3 million to support the Government of Egypt's Ministry of Investment efforts to eliminate conflicting and obsolete investment regulations in order to help reduce corruption.

- $2.0 million to support the Egyptian Ministry of Justice to enhance technical judicial capacity in economic courts.

- $1.7 million to support the High Elections Committee to increase voter awareness, improve administration of electoral processes, and expand public understanding and participation. The implementing partner is the International Foundation for Electoral Systems (IFES).

- $1.0 million to address gender-based violence (GBV) in Egypt by supporting activities such as awareness campaigns and community level mentoring to empower women and girls. The implementing partner is UN Women.

- $1.0 million in FY2016 (DF) to address violence against girls, including female genital mutilation (FGM). Activities could include outreach to improve knowledge of the harm that practices such as FGM, early marriage, and domestic violence bring to children. They could also provide lawyers, advocates, and civil society organizations with tools to combat such practices.

The Egyptian-American Enterprise Fund (EAEF)

In reaction to the political upheaval and economic dislocation that swept across the Arab world beginning in late 2010, the Obama Administration and Congress considered how best to support Arab citizens demanding political and economic change. After popular uprisings unexpectedly unseated authoritarian governments in Tunisia and Egypt in early 2011, the Administration and Members of Congress debated the appropriate types, scope, and scale of U.S. "transition" assistance. They found common support for the use of enterprise funds, which are private-sector entities funded by the U.S. government whose purpose is to promote the development of the private sector in foreign countries. They achieve this goal through a range of assistance instruments, including equity investments, microcredit lending, technical assistance to entrepreneurs, leveraging of private sector investment capital, and other means. Shared support for enterprise funds stemmed, in part, from a sense that socioeconomic grievances—such as high unemployment, bureaucratic red tape, and high-level corruption—were potent drivers of regional unrest.

In May 2011, then-President Obama laid out his Administration's initial response to the so-called "Arab Spring" by remarking that U.S. officials are "working with Congress to create Enterprise Funds to invest in Tunisia and Egypt. And these will be modeled on funds that supported the transitions in Eastern Europe after the fall of the Berlin Wall."102 In December 2011, Congress authorized the establishment of enterprise funds in Tunisia and Egypt (P.L. 112-74, Division I, §7041(b)).103

The Egyptian-American Enterprise Fund (EAEF) was established by grant agreement with USAID on March 23, 2013. According to USAID, current agency planning documents anticipate that total EAEF capitalization is expected to be $300 million; to date, the fund has received $242.4 million in obligated funds. Funding tranches are cleared through normal channels within USAID and the State Department and notified to Congress. As additional tranches are added to the funds' total budgets, the grant agreements are amended. The EAEF is a nonprofit, nonstock U.S. corporation with a board of directors composed of six private U.S. citizens and three private Egyptian citizens. To date, the EAEF has made five equity investments totaling $97.3 million (Table A-1).

|

Company |

Company Type/Sector |

Investment Amount |

|

Fawry |

Electronic Payments |

$20,000,000 |

|

Sarwa |

Consumer Finance |

$56,100,000 |

|

SmartCare |

Health Insurance |

$1,200,000 |

|

Algebra Fund |

Early-Stage Technology Investment Fund |

$10,000,000 |

|

Tanmiyah |

Mid-Cap Non-Tech Investment Fund |

$10,000,000 |

|

Total Investments |

$97,300,000 |

Source: USAID communication with CRS, April 28, 2017

Table A-2. U.S. Foreign Assistance to Egypt: 1946-2017

$'s in millions (calculated in historical dollars—not adjusted for inflation)

|

Year |

Military |

Economic |

Annual Total |

|

1946 |

n/a |

$9,600,000 |

$9,600,000 |

|

1948 |

n/a |

$1,400,000 |

$1,400,000 |

|

1951 |

n/a |

$100,000 |

$100,000 |

|

1952 |

n/a |

$1,200,000 |

$1,200,000 |

|

1953 |

n/a |

$12,900,000 |

$12,900,000 |

|

1954 |

n/a |

$4,000,000 |

$4,000,000 |

|

1955 |

n/a |

$66,300,000 |

$66,300,000 |

|

1956 |

n/a |

$33,300,000 |

$33,300,000 |

|

1957 |

n/a |

$1,000,000 |

$1,000,000 |

|

1958 |

n/a |

$601,000 |

$601,000 |

|

1959 |

n/a |

$44,800,000 |

$44,800,000 |

|

1960 |

n/a |

$65,900,000 |

|

|

1961 |

n/a |

$73,500,000 |

$73,500,000 |

|

1962 |

n/a |

$200,500,000 |

$200,500,000 |

|

1963 |

n/a |

$146,700,000 |

$146,700,000 |

|

1964 |

n/a |

$95,500,000 |

$95,500,000 |

|

1965 |

n/a |

$97,600,000 |

$97,600,000 |

|

1966 |

n/a |

$27,600,000 |

$27,600,000 |

|

1967 |

n/a |

$12,600,000 |

$12,600,000 |

|

1972 |

n/a |

$1,500,000 |

$1,500,000 |

|

1973 |

n/a |

$800,000 |

$800,000 |

|

1974 |

n/a |

$21,300,000 |

$21,300,000 |

|

1975 |

n/a |

$370,100,000 |

$370,100,000 |

|

1976 |

n/a |

$464,300,000 |

$464,300,000 |

|

1976tq |

n/a |

$552,501,000 |

$552,501,000 |

|

1977 |

n/a |

$907,752,000 |

$907,752,000 |

|

1978 |

$183,000 |

$943,029,000 |

$943,212,000 |

|

1979 |

$1,500,379,000 |

$1,088,095,000 |

$2,588,474,000 |

|

1980 |

$848,000 |

$1,166,423,000 |

$1,167,271,000 |

|

1981 |

$550,720,000 |

$1,130,449,000 |

$1,681,169,000 |

|

1982 |

$902,315,000 |

$1,064,936,000 |

$1,967,251,000 |

|

1983 |

$1,326,778,000 |

$1,005,064,000 |

$2,331,842,000 |

|

1984 |

$1,366,458,000 |

$1,104,137,000 |

$2,470,595,000 |

|

1985 |

$1,176,398,000 |

$1,292,008,000 |

$2,468,406,000 |

|

1986 |

$1,245,741,000 |

$1,293,293,000 |

$2,539,034,000 |

|

1987 |

$1,301,696,000 |

$1,015,179,000 |

$2,316,875,000 |

|

1988 |

$1,301,477,000 |

$873,446,000 |

$2,174,923,000 |

|

1989 |

$1,301,484,000 |

$968,187,000 |

$2,269,671,000 |

|

1990 |

$1,295,919,000 |

$1,093,358,000 |

$2,389,277,000 |

|

1991 |

$1,301,798,000 |

$998,011,000 |

$2,299,809,000 |

|

1992 |

$1,301,518,000 |

$933,320,000 |

$2,234,838,000 |

|

1993 |

$1,302,299,892 |

$753,532,569 |

$2,055,832,461 |

|

1994 |

$1,329,014,520 |

$615,278,400 |

$1,944,292,920 |

|

1995 |

$1,342,039,999 |

$975,881,584 |

$2,317,921,583 |

|

1996 |

$1,373,872,023 |

$824,526,772 |

$2,198,398,795 |

|

1997 |

$1,304,889,154 |

$811,229,175 |

$2,116,118,329 |

|

1998 |

$1,303,343,750 |

$833,244,554 |

$2,136,588,304 |

|

1999 |

$1,351,905,310 |

$862,062,972 |

$2,213,968,282 |

|

2000 |

$1,333,685,882 |

$742,458,662 |

$2,076,144,544 |

|

2001 |

$1,299,709,358 |

$393,734,896 |

$1,693,444,254 |

|

2002 |

$1,301,367,000 |

$1,046,193,773 |

$2,347,560,773 |

|

2003 |

$1,304,073,715 |

$646,856,657 |

$1,950,930,372 |

|

2004 |

$1,318,119,661 |

$720,241,711 |

$2,038,361,372 |

|

2005 |

$1,294,700,384 |

$495,849,549 |

$1,790,549,933 |

|

2006 |

$1,301,512,728 |

$351,242,865 |

$1,652,755,593 |

|

2007 |

$1,305,235,109 |

$737,348,766 |

$2,042,583,875 |

|

2008 |

$1,294,902,533 |

$314,498,953 |

$1,609,401,486 |

|

2009 |

$1,301,332,000 |

$688,533,320 |

$1,989,865,320 |

|

2010 |

$1,301,900,000 |

$301,154,735 |

$1,603,054,735 |

|

2011 |

$1,298,779,449 |

$240,529,294 |

$1,539,308,743 |

|

2012 |

$1,302,233,562 |

$90,260,725 |

$1,392,494,287 |

|

2013 |

$1,239,659,511 |

$330,576,763 |

$1,570,236,274 |

|

2014 |

$274,031 |

$179,289,264 |

$179,563,295 |

|

2015 |

$1,345,091,943 |

$222,673,006 |

$1,567,764,949 |

|

2016 |

$1,105,882,379 |

$133,408,861 |

$1,239,291,240 |

|

2017 |

$141,745,115 |

$141,745,115 |

|

|

Totals |

$45,829,536 |

$32,634,642 |

$78,464,177,834 |

Source: U.S. Overseas Loans and Grants, Obligations and Loan Authorizations, July 1, 1945-September 30, 2016.

Notes: This chart does not account for the re-purposing of assistance funds which had been previously obligated for Egypt.