On December 6, 2017, the House of Representatives passed the Concealed Carry Reciprocity Act of 2017 (H.R. 38). The term "concealed carry" is commonly used to refer to state laws that allow an individual to carry a weapon—generally a handgun—on one's person in a concealed manner for the purposes of self-defense in public (outside one's home or fixed place of business). Federal law allows certain active-duty and retired law enforcement officers to carry concealed firearms interstate, irrespective of some state laws, but they must first be qualified and credentialed by their agencies of employment or from which they retired. For the most part, however, firearms carriage is a matter principally regulated by state law.

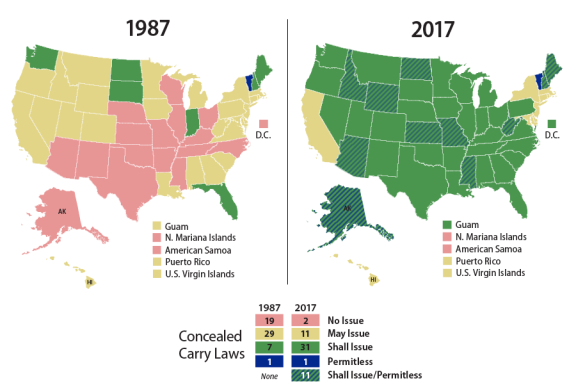

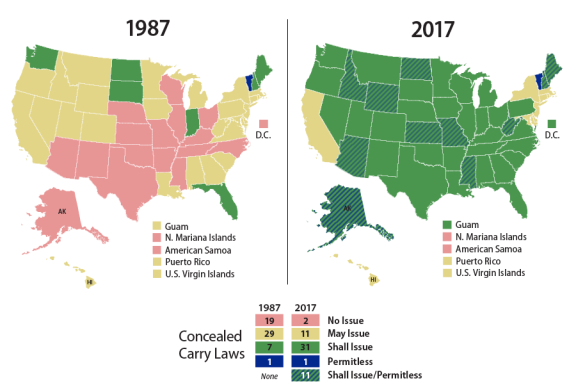

Typically, there are two basic types of concealed carry laws: (1) "shall issue," meaning permits are generally issued to all eligible applicants; and (2) "may issue," which are more restrictive, meaning authorities enjoy a greater degree of discretion whether to issue permits to individuals. In 1987, concealed carry was generally prohibited in 16 states, the District of Columbia, and three U.S. territories. Twenty-six states and two territories had "may issue" laws, and seven had "shall issue" laws. One state—Vermont—allowed "permitless" carry, meaning otherwise firearms-eligible individuals could carry without a permit. Over the past 31 years, state laws have shifted from prohibitive "no issue" or restrictive "may issue" laws to more permissive "shall issue," or more recently, "permitless" laws (see Figure 1).

Today, all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and three of the five U.S. territories allow some form of concealed carry of firearms in public. Forty-one states and the District have "shall issue" laws and 11 of those states allow "permitless" carry, as Vermont still does. Twenty-four "shall issue" states recognize all valid permits issued by any other state. One "may issue" state and 15 "shall issue" states recognize anywhere from 9 to 43 other states. One "shall issue" state and nine "may issue" states (plus the District) do not recognize any other state's permits. Nevertheless, state laws still vary considerably in their basic terms of issuance for such permits, such as eligibility criteria, background check extensiveness, eligibility monitoring, credentialing, and law enforcement validation.

|

Figure 1. Concealed Carry Handgun Laws, 1987 v. 2017

|

|

|

Sources: Texas Handgun Association, A History of Concealed Carry, 1976-2011, http://txcha.org/texas-ltc-information/a-history-of-concealed-carry/; U.S. Department of the Treasury, Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms, State Laws and Published Ordinances—Firearms, 17th ed., ATF P 5300.5 (12-86), and Handgunlaw.us, http://www.handgunlaw.us/.

Notes: Gauging the comparative restrictiveness or permissiveness of state concealed carry laws is a matter of legal interpretation. The categorizations reflected in the maps above are based on CRS analysis of state and territorial laws.

|

The concealed-carry debate has been propelled by two landmark Supreme Court decisions. In District of Columbia v. Heller, the Court found in 2008 that the District's handgun ban violated an individual's right under the Second Amendment to possess a handgun in his home for lawful purposes such as self-defense. Two years later, in McDonald v. City of Chicago, the Court found that this right to possess a firearm lawfully for self-defense under the Second Amendment applies to the states by way of the Fourteenth Amendment. Although these decisions limit a state, city, or local government's ability to prohibit handguns outright, they do not delineate fully what constitutes permissible gun control under the Second Amendment.

The House-passed H.R. 38 would

- require any state that allows concealed carry of firearms for its own residents to recognize any resident of another state as authorized to carry a concealed handgun, if that nonresident is authorized to carry a concealed firearm in any other state with a permit, or is allowed to carry a concealed firearm without a permit in his home state of residence, as long as he is otherwise eligible to receive and possess a firearm;

- allow a person to acquire a nonresident concealed-carry permit from another state with different eligibility requirements and return to his home state and legally carry a concealed handgun;

- allow persons authorized by any state to carry concealed firearms to be exempt from the federal Gun Free School Zones Act (GFSZA) and other laws restricting carrying on certain federal lands;

- exempt from GFSZA any qualified and credentialed law enforcement officers authorized under federal law to carry concealed firearms interstate;

- extend interstate concealed-carry privileges to federal judges; and

- provide a right of action for persons deprived of any "right, privilege, or immunity" secured under its provisions.

H.R. 38 would not supersede state laws that allow private property owners to restrict concealed firearms on their property, or state laws that restrict firearms on certain state and local government property. Nor would it supersede federal laws that restrict firearms in certain sensitive areas, such as on commercial aircraft, in controlled areas of airports, federal buildings, Capitol buildings and grounds, and elementary and secondary school zones.

H.R. 38 would compel all states to honor concealed-carry privileges afforded to any individual by another state, as long as the carrier was properly credentialed. For a "permitless" state resident, proper credentialing would include a valid government-issued identification document with the bearer's photograph. All others would also be required to carry a concealed-carry permit.

At issue for Congress is whether individuals authorized to carry concealed firearms by one state should be allowed to carry a concealed handgun in another state, even when the terms of issuance in the host state and the permitting state may differ greatly. Supporters of H.R. 38 aver that law-abiding citizens should be able to travel interstate without worrying about conflicting concealed-carry laws. Opponents view concealed carry as a privilege only to be extended to individuals who can demonstrate to the authorities a good cause and that they are worthy of the public trust. Proponents also contend that criminals are less likely to victimize individuals who could be armed. Opponents argue that introducing firearms into potentially life-threatening situations increases the chances that a firearm could be misused and innocent persons killed or wounded. H.R. 38 awaits Senate consideration.