The Bureau of Prisons (BOP) is the largest correctional agency in the country in terms of the number of prisoners under its jurisdiction.1 BOP was established in 1930 to house federal inmates, professionalize the prison service, and ensure consistent and centralized administration of the federal prison system.2 BOP must confine any offender convicted and sentenced to a term of imprisonment in a federal court.

Changes in federal criminal justice policy since the early 1980s—enforcing a growing number of federal crimes, replacing indeterminate sentencing with a determinate sentencing structure through sentencing guidelines, and increasing the number of federal offenses subject to mandatory minimum sentences—led to rapid growth in the federal prison population. The total number of inmates under BOP's jurisdiction increased from approximately 25,000 in FY1980 to over 219,000 in FY2013.3 Between FY1980 and FY2013, the federal prison population increased, on average, by approximately 5,900 inmates annually. However, since the peak in FY2013, the number of inmates in the federal prison system decreased each subsequent fiscal year to approximately 192,000 inmates in FY2016.4

Generally, the increase in the federal prison population necessitated an increase in appropriations for BOP's operations and infrastructure. In FY1980, Congress appropriated $330.0 million for BOP; by FY2016, the total appropriation for BOP reached $7.479 billion, which was the largest nominal appropriation ever for BOP. Appropriations for BOP have generally continued to increase since FY2013 (FY2017 was the exception) even though the prison population has decreased since that time. Increasing appropriations for BOP, despite the declining prison population, could be the result of a growing per capita cost of incarceration or BOP's need to maintain staffing levels commensurate with the size of the prison population.

This report provides an overview of BOP's appropriations since FY1980. Specifically, this report examines trends in BOP's total appropriations, changes in funding for BOP's appropriations account, and trends in funding for the decision units under BOP's appropriations accounts. The report provides a brief analysis of how the Administration's requested funding for BOP compares to enacted appropriations. It also discusses changes in the per capita cost of incarceration and how appropriations for BOP have changed relative to those for the Department of Justice, both issues that have been of interest to policymakers.

Appropriations for BOP

Trends in BOP's Total Appropriations

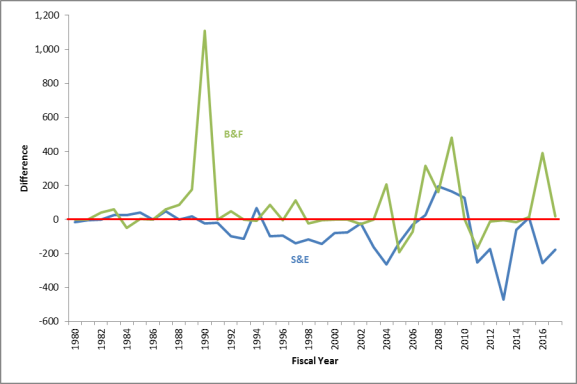

As shown in Figure 1, BOP's appropriations increased by nearly $7.149 billion from FY1980 to FY2016. FY2016 was the peak, in nominal terms, for BOP's funding. BOP's funding decreased by $340 million in FY2017. Between FY1980 and FY2016, the average annual increase in BOP's appropriations was approximately $199 million. The increasing appropriations for BOP generally coincided with an increase in the number of inmates under BOP's jurisdiction. This trend changed somewhat in recent years. BOP's appropriations increased each fiscal year from FY2014 to FY2016 even though the total number of federal inmates decreased in each of those fiscal years.

Figure 1 also shows that BOP's appropriations have increased at a rate that is significantly greater than inflation, as indicated by the positive slope on the inflation-adjusted line in the figure. In FY2017 inflation-adjusted dollars, BOP's appropriations increased 787% from FY1980 to FY2016. BOP's appropriations increased 732%, in inflation-adjusted dollars, when accounting for the decrease in appropriations for FY2017.5

It has been argued that even though appropriations for BOP are discretionary, they are effectively mandatory because "[b]y law, the BOP must accept and provide for all [f]ederal inmates, including but not limited to inmate care, custodial staff, contract beds, food, and medical costs. BOP cannot control the number of inmates sentenced to prison, and unlike other [f]ederal agencies, cannot limit assigned workloads and thereby control operating costs."6

|

Figure 1. Nominal and Adjusted Appropriations for the Bureau of Prisons, FY1980-FY2017 Appropriations in billions of dollars |

|

|

Source: U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Prisons. Notes: Nominal appropriations were adjusted for inflation using the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) Chained Price Index presented in Table 10.1 of the FY2018 Budget of the U.S. Government. Inflation-adjusted amounts are presented in FY2017 dollars. The spike in BOP's funding for FY1990 was the result of Congress appropriating $1.512 billion for the B&F account (see Table A-1). The FY2013 enacted amount reflects the amount sequestered per the Budget Control Act of 2011(P.L. 112-25). |

Trends in BOP Appropriations by Account

Nearly all of BOP's operations are funded through annual appropriations provided by Congress.7 BOP's annual budget is divided between two major accounts: Salaries and Expenses (S&E) and Buildings and Facilities (B&F). The S&E account (i.e., the operating budget) provides for the custody and care of federal inmates and for the daily maintenance and operations of correctional facilities, regional offices, and BOP's central office in Washington, DC. It also provides funding for the incarceration of federal inmates in state, local, and private facilities. The B&F account (i.e., the capital budget) provides funding for the construction of new facilities and the modernization, repair, and expansion of existing facilities.8

|

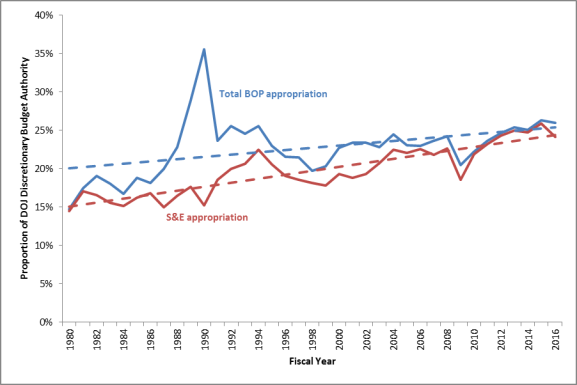

Figure 2. Appropriations for BOP, by Account, FY1980-FY2017 Appropriations in billions of nominal dollars |

|

|

Source: U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Prisons. Notes: Amounts in Figure 2 include all supplemental appropriations and any rescissions of enacted budget authority, but they do not include rescissions of unobligated balances. From FY1980 to FY1995, funding for the National Institute of Corrections (NIC) was included in a separate account. Since FY1996, funding for the NIC has been included in the S&E account. In this figure, funding for the NIC for FY1980-FY1995 was added to the S&E account to make funding for the S&E account comparable across fiscal years. The FY2013-enacted amount reflects the amount sequestered per the Budget Control Act of 2011(P.L. 112-25). |

Two trends emerge from a review of BOP's appropriations from FY1980 through FY2017. First, while there has been a nearly continuous increase in the overall appropriations for BOP, it is in large part driven by an almost continuous increase in appropriations for BOP's Salaries and Expenses (S&E) account since FY1980 (see Figure 2). The one exception to this trend is the appropriation for FY2013, which is lower than the FY2012 appropriation due to the sequestration ordered pursuant to the Budget Control Act of 2011 (P.L. 112-25).

In general, appropriations for BOP's S&E account increased as the prison population increased, which is not surprising given that the S&E account funds the operation of the federal prison system, including the salaries and benefits of both correctional officers and other institutional employees. BOP hired more officers and other employees as it opened more prisons and supervised more inmates. However, funding for the S&E account has continued to increase, albeit at a reduced rate, even though the prison population has decreased each fiscal year from FY2013 to FY2016.9 BOP has continued to request increased funding for the S&E account even though it is housing fewer inmates, and Congress has continued to increase appropriations, though generally below the level requested. BOP notes that additional funding is needed to cover the cost of pay raises and benefits for employees, as well as to cover growing costs associated with inmate health care, food, and prison utilities. Also, during some of these years, BOP requested additional funding to increase its capacity to provide programs and services for inmates (e.g., reentry programming and mental health treatment) and to hire more staff to increase institutional safety, something BOP might not have been able to do during the years when the inmate population was growing at a sustained clip and resources were dedicated to providing basic levels of care and security.10 In addition, even though there are fewer inmates under the BOP's jurisdiction, the federal prison system is still operating over its rated capacity.11 In short, the federal prison population has not declined enough that BOP could start to close prisons and reduce staff, which would help bring down the cost of the federal prison system.

Second, funding for the Buildings and Facilities (B&F) account is more irregular, with Congress appropriating more in some fiscal years and less in others. The irregularity in B&F funding is likely the result of the cyclical nature of the expansion of BOP's prison capacity as more offenders entered the federal prison system. Congress would appropriate funding to help boost bedspace in the federal prison system; BOP would use that funding to plan and construct new prisons. Upon completion of the new prison, BOP's capacity would expand, but it would need to expand again in later years as the prison population continued to grow, and the cycle would begin anew. In FY2017, a $400 million decrease in funding for the B&F account was the primary reason why BOP's total appropriation decreased for FY2017.12

Trends in BOP's Funding by Decision Unit

Each of BOP's two appropriations accounts are divided into decision units, each of which fund specific aspects of BOP operations. The S&E account is divided into four decision units:

- Inmate Care and Programs: This decision unit covers the cost of inmate food, medical supplies, institutional and release clothing, welfare services, transportation, gratuities, staff salaries, and other operational costs directly related to providing inmate care. It provides funding for inmate programs, including education and vocational training, psychological services, religious programs, and drug treatment. This decision unit also covers costs associated with regional and central office administration and support related to providing inmate care.

- Institution Security and Administration: This decision unit funds institution maintenance, motor pool operations, powerhouse operations, institution security, and other administrative functions. It also covers costs associated with regional and central office administrative and management support functions such as research and evaluation, systems support, financial management, budget functions, safety, and legal counsel.

- Contract Confinement: This decision unit provides for the costs associated with the confinement of federal inmates in contract facilities, which include private prisons, Residential Reentry Centers (RRC), state and local facilities, and home confinement. It provides funding for the management and oversight of contract confinement functions. This decision unit also provides funding for the National Institute of Corrections (NIC).

- Management and Administration: This decision unit provides funding for costs associated with general administration and provides funding for BOP's central office, regional offices, and staff training centers.

Since FY1999, approximately 80% of BOP's S&E funding has gone to combined appropriations for the Inmate Care and Programs and the Institution Security and Administration decision units. Funding for these two decision units has increased at about the same rate as funding for the S&E account overall. From FY1999 to FY2017, funding for the Inmate Care and Programs decision unit increased 141% and funding for the Institution Security and Administration decision unit increased 123%. In comparison, funding for the S&E account increased 143% over the same time period.

Funding for the Contract Confinement decision unit increased 295% between FY1999 and FY2017. The steeper increase in funding for the Contract Confinement decision unit comes as BOP has relied on confining more inmates in contract facilities, along with growing demand for RRC bedspace (a byproduct of more inmates being imprisoned and eventually released after serving their prison sentences).

While funding for the Contract Confinement decision unit outpaced the growth of funding for the S&E account overall, funding for the Management and Administration decision unit grew at a rate below that of the S&E account. From FY1999 to FY2017, funding for the Management and Administration decision unit increased 74%.

The B&F account is divided into two decision units:

- New Construction: This decision unit covers lease payments for the Oklahoma Transfer Center, the salaries and administrative costs of staff involved in new prison construction, construction of inmate work program areas and expansion and conversion projects (i.e., additional special housing unit space).

- Modernization and Repair: This decision unit provides resources to undertake essential rehabilitation, modernization, and renovation of correctional facilities and their grounds. This includes modifications to facilities to accommodate correctional programs, repair or replace utilities systems and other critical infrastructure, repair projects at existing institutions, and maintain all systems and structures in a good state of repair.

In 10 of the 19 fiscal years since FY1999, a majority of the funding for the B&F account has been dedicated for new prison construction. In fiscal years where funding for the B&F account increased, funding for new prison construction generally increased. On average, Congress appropriated $333 million for the B&F account from FY1999 to FY2017. Fiscal years in which funding for modernization and repair accounted for a majority of B&F funding were usually years in which funding for the B&F account was significantly below this average, usually when total B&F funding was less than $100 million.

Requested Versus Enacted Funding for BOP

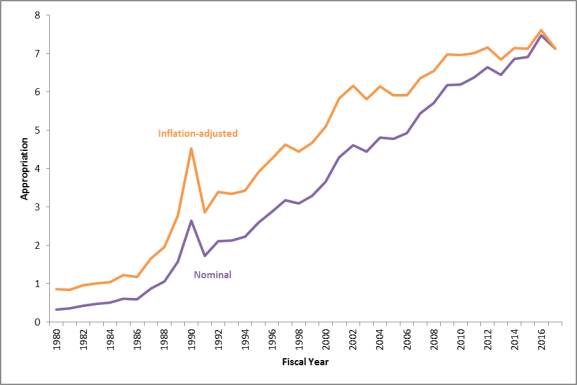

A comparison of BOP's annual appropriations for its S&E and B&F accounts to the Administration's request for both accounts shows that Congress has been more likely to fund the Administration's request for prison construction and less likely to fully fund the Administration's request for operating the federal prison system (see Figure 3). The requested appropriation indicates what BOP believed it would need to properly manage the prison population each fiscal year. The data suggest that in many fiscal years BOP operated with a budget below what it felt was adequate.

The data presented in Figure 3 show that from FY1980 to FY2017, Congress appropriated less than the Administration's request for the B&F account 16 times. Over the same time period Congress appropriated less than the Administration's request for the S&E account 24 times.13 In contrast, however, the amount appropriated for the S&E account between FY2007 and FY2010 actually exceeded the Administration's request. The additional amounts provided by Congress during these fiscal years, as noted by the House Committee on Appropriations, were to compensate for underfunding BOP in previous years, which resulted in inadequate staffing levels and shortfalls in inmate programs.14 In the past, both the House and the Senate appropriations committees reported that they felt the Administration's requests for BOP were inadequate, which did not allow BOP to meet its basic operational needs.15 However, Congress has not raised similar concerns in more recent fiscal years. Appropriations for the S&E account have been below the Administration's request for six of the past seven fiscal years, by an average of $232 million.

Per Capita Cost of Incarceration

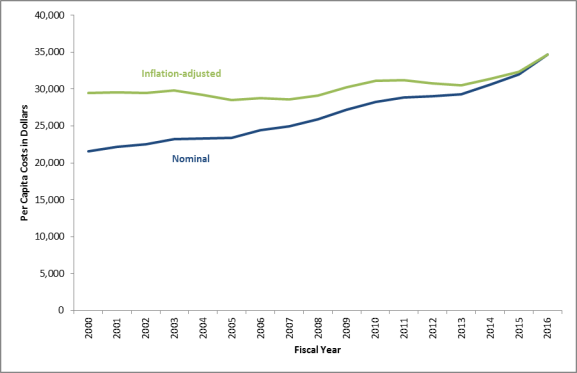

As noted above, appropriations for BOP have continued to increase even though the federal prison population has decreased in recent years. This trend might be partly explained by the increasing per capita cost for incarceration. As show in Figure 4, the nominal per capita cost of incarceration has increased from approximately $22,000 per inmate in FY2000 to almost $35,000 in FY2016, a 61% rise.16 From FY2000 to FY2012, the per capita cost of incarceration roughly increased at the same rate as inflation. However, since FY2013 increases in the per capita cost have started to outstrip inflation.

The increasing per capita cost of incarceration is partly due to inflationary pressures, such as the increasing cost of health care, food, clothing, and utilities.17 However, it is notable that the per capita cost of incarceration has increased at a greater rate than inflation since FY2013, which coincides with the decreasing prison population.18 Stable or increasing obligations combined with a decreasing prison population will result in increasing per capita costs because the shared inmate expenses are dispersed across fewer inmates.

Per capita costs are not equivalent to marginal costs (i.e., what it costs BOP to incarcerate one additional inmate). For example, if the per capita cost of incarceration is $22,000 per inmate and BOP's prison population decreased by 1,000 inmates, it does not mean that BOP would save $22 million. Per capita costs do not equate to marginal costs because per capita costs reflect the total amount BOP obligates in a fiscal year divided by that fiscal year's average daily population. Some costs (e.g., food and clothing expenses) would decrease if BOP incarcerated fewer inmates. However, obligations also account for items like staff salaries, which might not change until the prison population decreases to a point where BOP could close prisons and reduce staff. For example, if all of BOP's high security facilities hold 10% more inmates than their rated capacity and BOP's prison population decreases to a point where these facilities hold the same number of inmates as their rated capacity, it is likely that BOP would not reduce staffing at those prisons, which would mean that obligations for high security facilities for that fiscal year would not decline significantly.

|

|

Source: U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Prisons. Notes: Nominal appropriations were adjusted for inflation using the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) Chained Price Index presented in Table 10.1 of the FY2018 Budget of the U.S. Government. Inflation-adjusted amounts are presented in FY2016 dollars. |

Appropriations for BOP Relative to Those for the Department of Justice

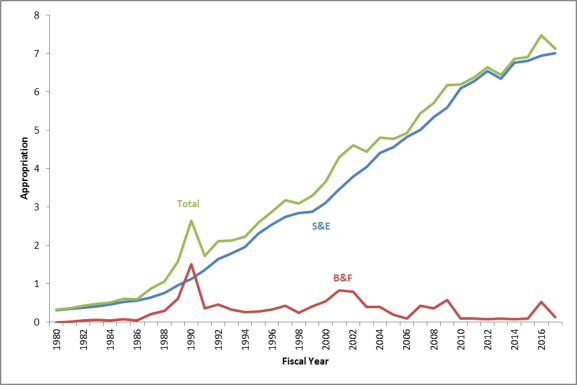

One concern among some policymakers is that BOP's expanding budget is starting to consume a larger share of the Department of Justice's (DOJ) overall annual appropriations. Figure 5 shows what proportion of DOJ's annual discretionary budget was dedicated to BOP. BOP's overall budget is more susceptible to fluctuations due to changes in year-to-year appropriations for BOP's B&F account. The trend lines (the dashed lines in the figure) show that since FY1980, both BOP's total budget and the S&E account have, in general, encompassed a growing share of DOJ's annual appropriations. The noticeable spike in BOP's share of DOJ's annual appropriations in FY1990 was the result of Congress appropriating more than $1 billion for the B&F account. In addition, the decrease in BOP's share of DOJ's appropriations observed in FY2009, a break in a general upward trend that started in FY2000, was the result of Congress appropriating an additional $4 billion for DOJ under the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (P.L. 111-5).

Appendix A. BOP Appropriations: Total and by Decision Unit

Table A-1. Requested and Enacted Appropriations for the Bureau of Prisons, FY1980-FY2017

Appropriations in thousands of dollars

|

Request |

Appropriated |

|||||

|

Fiscal Year |

Salaries and Expenses |

Buildings and Facilities |

Total |

Salaries and Expenses |

Buildings and Facilities |

Total |

|

1980 |

$338,051 |

$5,960 |

$344,011 |

$323,884 |

$5,960 |

$329,844 |

|

1981 |

355,258 |

10,466 |

365,724 |

351,759 |

10,020 |

361,779 |

|

1982 |

377,267 |

14,731 |

391,998 |

378,016 |

56,481 |

434,497 |

|

1983 |

387,587 |

6,667 |

394,254 |

412,133 |

66,667 |

478,800 |

|

1984 |

437,928 |

97,142 |

535,070 |

464,850 |

47,711 |

512,561 |

|

1985 |

497,662 |

82,556 |

580,218 |

536,932 |

86,043 |

622,975 |

|

1986 |

560,004 |

46,063 |

606,067 |

561,480 |

44,082 |

605,562 |

|

1987 |

608,302 |

159,152 |

767,454 |

656,941 |

219,249 |

876,190 |

|

1988 |

771,360 |

210,334 |

981,694 |

772,013 |

297,076 |

1,069,089 |

|

1989 |

943,530 |

436,554 |

1,380,084 |

962,016 |

612,914 |

1,574,930 |

|

1990 |

1,162,666 |

401,332 |

1,563,998 |

1,138,778 |

1,511,953 |

2,650,731 |

|

1991 |

1,381,889 |

374,358 |

1,756,247 |

1,363,645 |

374,358 |

1,738,003 |

|

1992 |

1,748,056 |

411,593 |

2,159,649 |

1,649,121 |

462,090 |

2,111,211 |

|

1993 |

1,906,806 |

339,225 |

2,246,031 |

1,793,470 |

339,225 |

2,132,695 |

|

1994 |

1,895,214 |

276,850 |

2,172,064 |

1,962,605 |

269,543 |

2,232,148 |

|

1995 |

2,417,096 |

191,021 |

2,608,117 |

2,319,722 |

276,301 |

2,596,023 |

|

1996 |

2,640,417 |

337,228 |

2,977,645 |

2,546,893a |

334,728 |

2,881,621 |

|

1997 |

2,888,316 |

320,924 |

3,209,240 |

2,748,427b |

435,200 |

3,183,627 |

|

1998 |

2,965,642 |

278,057 |

3,243,699 |

2,847,777c |

255,133 |

3,102,910 |

|

1999 |

3,032,494 |

413,997 |

3,446,491 |

2,888,853d |

410,997 |

3,299,850 |

|

2000 |

3,191,928 |

558,791 |

3,750,719 |

3,111,073e |

556,780 |

3,667,853 |

|

2001 |

3,545,769 |

835,660 |

4,381,429 |

3,469,739 |

833,822 |

4,303,561 |

|

2002 |

3,829,437 |

833,273 |

4,662,710 |

3,805,118 |

807,808 |

4,612,926 |

|

2003 |

4,208,459 |

396,609 |

4,605,068 |

4,044,788 |

396,632 |

4,441,420 |

|

2004 |

4,677,214 |

187,900 |

4,865,114 |

4,414,313 |

393,515 |

4,807,828 |

|

2005 |

4,706,232 |

397,700 |

5,103,932 |

4,571,385 |

205,076 |

4,776,461 |

|

2006 |

4,859,649 |

170,112 |

5,029,761 |

4,830,160 |

99,961 |

4,930,121 |

|

2007 |

4,987,059 |

117,102 |

5,104,161 |

5,012,433 |

432,425 |

5,444,858 |

|

2008 |

5,151,440 |

210,003 |

5,361,443 |

5,346,740 |

372,720 |

5,719,460 |

|

2009 |

5,435,754 |

95,807 |

5,531,561 |

5,600,792 |

575,807 |

6,176,599 |

|

2010 |

5,979,831 |

96,744 |

6,076,575 |

6,106,231 |

99,155 |

6,205,386 |

|

2011 |

6,533,779 |

269,733 |

6,803,512 |

6,282,410 |

98,957 |

6,381,367 |

|

2012 |

6,724,266 |

99,934 |

6,824,200 |

6,551,281 |

90,000 |

6,641,281 |

|

2013 |

6,820,217 |

99,189 |

6,919,406 |

6,349,248 |

95,356 |

6,444,604 |

|

2014 |

6,831,150 |

105,244 |

6,936,394 |

6,769,000 |

90,000 |

6,859,000 |

|

2015 |

6,804,000 |

90,000 |

6,894,000 |

6,815,000 |

106,000 |

6,921,000 |

|

2016 |

7,204,158 |

140,564 |

7,344,722 |

6,948,500 |

530,000 |

7,478,500 |

|

2017 |

7,186,225 |

113,022 |

7,299,247 |

7,008,800 |

130,000 |

7,138,800 |

Source: U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Prisons.

Notes: Amounts in Table A-1 include all supplemental appropriations and any rescissions of enacted budget authority, but they do not include rescissions of unobligated balances. From FY1980 to FY1995, funding for the National Institute of Corrections (NIC) was included in a separate account. Since FY1996, funding for the NIC has been included in the S&E account. In this table, funding for the NIC for FY1980-FY1995 was added to the S&E account to make funding for the S&E account comparable across fiscal years. The FY2013-enacted amount reflects the amount sequestered per the Budget Control Act of 2011(P.L. 112-25).

a. Includes $13.5 million appropriated from the Violent Crime Reduction Trust Fund (VCRTF).

b. Includes $25.2 million appropriated from the VCRTF.

c. Includes $26.1 million appropriated from the VCRTF.

Table A-2. Appropriations for BOP, by Decision Unit, FY1999-FY2017

Appropriations in thousands of dollars

|

Salaries and Expenses |

Buildings and Facilities |

|||||

|

Fiscal Year |

Inmate Care and Programs |

Institution Security and Administration |

Contract Confinement |

Management and Administration |

New Construction |

Modernization and Repair |

|

1999 |

$1,090,148 |

$1,401,349 |

$255,062 |

$142,249 |

$322,963 |

$88,034 |

|

2000 |

1,123,856 |

1,494,809 |

344,773 |

147,635 |

441,003 |

115,777 |

|

2001 |

1,208,480 |

1,601,518 |

511,579 |

148,162 |

710,816 |

123,006 |

|

2002 |

1,311,335 |

1,722,567 |

620,145 |

151,071 |

675,040 |

132,768 |

|

2003 |

1,454,481 |

1,868,538 |

567,365 |

154,404 |

262,956 |

133,676 |

|

2004 |

1,624,308 |

2,050,417 |

574,473 |

165,115 |

177,620 |

164,000 |

|

2005 |

1,682,656 |

2,094,917 |

627,135 |

166,677 |

25,372 |

179,704 |

|

2006 |

1,740,011 |

2,227,223 |

683,031 |

179,895 |

48,115 |

51,846 |

|

2007 |

1,774,048 |

2,297,055 |

757,851 |

183,479 |

368,875 |

63,550 |

|

2008 |

1,942,077 |

2,409,112 |

814,529 |

181,022 |

302,720 |

70,000 |

|

2009 |

2,070,002 |

2,495,196 |

840,933 |

194,661 |

465,180 |

110,627 |

|

2010 |

2,215,992 |

2,708,651 |

981,112 |

200,476 |

25,386 |

73,769 |

|

2011 |

2,294,174 |

2,783,664 |

996,772 |

207,800 |

25,335 |

73,622 |

|

2012 |

2,421,272 |

2,880,290 |

1,040,213 |

209,506 |

23,035 |

66,695 |

|

2013 |

2,424,620 |

2,717,938 |

1,017,297 |

189,393 |

23,649 |

71,707 |

|

2014 |

2,525,039 |

2,966,364 |

1,074,808 |

202,789 |

22,852 |

67,148 |

|

2015 |

2,587,936 |

3,002,827 |

1,011,505 |

211,347 |

25,000 |

81,000 |

|

2016 |

2,679,562 |

3,025,209 |

1,015,739 |

227,990 |

444,000 |

86,000 |

|

2017 |

2,625,439 |

3,129,075 |

1,006,522 |

247,764 |

50,000 |

80,000 |

Source: U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Prisons.

Notes: Amounts in this table include all supplemental appropriations and any rescissions of enacted budget authority, but they do not include rescissions of unobligated balances. The FY2013-enacted amount reflects the amount sequestered per the Budget Control Act of 2011(P.L. 112-25).

Appendix B. BOP Per Capita Costs

|

Security Level |

||||||

|

Fiscal Year |

All of BOP |

High |

Medium |

Low |

Minimum |

Federal Correctional Complexesa |

|

2000 |

$21,603 |

$26,518 |

$21,417 |

$18,407 |

$17,452 |

$21,360 |

|

2001 |

22,175 |

26,135 |

21,806 |

18,846 |

17,788 |

20,543 |

|

2002 |

22,518 |

27,456 |

21,473 |

19,228 |

18,770 |

21,538 |

|

2003 |

23,180 |

26,461 |

21,946 |

19,480 |

18,136 |

21,948 |

|

2004 |

23,267 |

26,951 |

21,896 |

19,242 |

17,647 |

21,764 |

|

2005 |

23,431 |

26,377 |

21,718 |

19,193 |

17,478 |

22,458 |

|

2006 |

24,439 |

25,398 |

23,648 |

20,834 |

17,291 |

23,152 |

|

2007 |

24,923 |

26,109 |

23,492 |

21,922 |

17,812 |

22,804 |

|

2008 |

25,895 |

27,924 |

24,065 |

23,373 |

19,635 |

23,958 |

|

2009 |

27,251 |

32,119 |

25,442 |

24,087 |

20,772 |

25,750 |

|

2010 |

28,282 |

33,858 |

26,248 |

25,377 |

21,005 |

27,267 |

|

2011 |

28,894 |

34,629 |

26,852 |

26,853 |

21,286 |

27,516 |

|

2012 |

29,027 |

34,046 |

26,686 |

27,166 |

21,694 |

27,683 |

|

2013 |

29,291 |

33,887 |

27,278 |

27,386 |

21,960 |

28,330 |

|

2014 |

30,621 |

35,718 |

28,536 |

28,425 |

23,232 |

29,617 |

|

2015 |

31,976 |

36,690 |

29,475 |

29,273 |

24,149 |

31,528 |

|

2016 |

34,703 |

39,716 |

32,614 |

31,991 |

27,295 |

33,589 |

Source: U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Prisons.

Notes: The per capita cost of incarceration for all of BOP includes direct costs for federal detention centers, administrative security facilities, medical referral centers, privately operated institutions, residential reentry centers, and contracts with state and local institutions. It also includes support costs for federal detention centers, administrative security facilities, and medical referral centers.

a. Federal correctional complexes (FCC) contain two or more facilities with different security levels on the same grounds. For example, FCC Allenwood (PA) contains high-, medium-, and low-security facilities.