Introduction

The Department of Defense (DOD) relies extensively on contractors to equip and support the U.S. military in peacetime and during military operations. Contractors design, develop, and build advanced weapon and business systems, construct military bases around the world, and provide services such as intelligence analysis, logistics, and base support.

Congress has long been frustrated with perceived cost overruns, waste, mismanagement, and fraud in defense acquisitions, and has spent significant effort attempting to reform and improve the process. Since the 1970s, there have been numerous efforts to comprehensively reform defense acquisition.1 Congress generally sets acquisition policy for the DOD through the annual National Defense Authorization Acts (NDAAs) as well as through stand-alone legislation, such as the Defense Acquisition Workforce Improvement Act of 1990,2 Federal Acquisition Streamlining Act of 1994,3 Clinger-Cohen Act of 1996,4 and Weapon System Acquisition Reform Act of 2009.5

This report provides a brief overview of selected acquisition-related provisions found in the NDAAs for FY2016 (P.L. 114-92), FY2017 (P.L. 114-328), and FY2018 (P.L. 115-91). This report also has a section on some of the more controversial and extensive changes in recent years:

- the changes to the role of the Chiefs of the Military Services and the Commandant of the Marine Corps (collectively referred to as the Service Chiefs) in the acquisition process,

- the breakup of the office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition, Technology, and Logistics (USD (AT&L)), and

- the shift of authority from the Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD) to the military departments.

Acquisition Reform in the FY2016-FY2018 NDAAs

In recent years, Congress has generally exercised its legislative powers to affect defense acquisitions through Title VIII of the NDAA, entitled Acquisition Policy, Acquisition Management, and Related Matters. In some years, the NDAA also contains titles specifically dedicated to aspects of acquisition, such as Title XVII of the FY2018 NDAA, entitled Small Business Procurement and Industrial Base Matters.6

Congress has been particularly active in legislating acquisition reform over the last three years. For FY2016-FY2018, NDAA titles specifically related to acquisition reform contained an average of 82 provisions (247 in total), compared to an average of 47 such provisions (466 in total) in the NDAAs for the preceding 10 fiscal years (see Appendix).7

Faster and More Efficient Acquisitions

The FY2016 NDAA sought to develop more timely and efficient ways for DOD and the Military Services to acquire goods and services. One provision expanded the use of rapid acquisition authority to support certain military operations.8 Another provision required DOD to develop guidance for rapidly acquiring middle tier programs (intended to be completed in two to five years), to include rapid prototyping and rapid fielding.9 Congress also required the development of streamlined alternative acquisition paths that maximize the use of flexibility allowed under the law to acquire critical national security capabilities.10

In addition to expanding existing flexibilities and trying to create new and quicker acquisition methods, Congress authorized the Secretary of Defense to, in certain circumstances, waive any provision of acquisition law or regulation if

(1) the acquisition of the capability is in the vital national security interest of the United States;

(2) the application of the law or regulation to be waived would impede the acquisition of the capability in a manner that would undermine the national security of the United States; and

(3) the underlying purpose of the law or regulation to be waived can be addressed in a different manner or at a different time.11

In the FY2017 NDAA, Congress reflected its concern with defense technology innovation, dedicating a number of sections to promoting integration and collaboration of the national technology and industrial base,12 and attempting to spur defense-related innovation among nontraditional defense and small businesses.13

Other Transaction Authority

Other transaction authority (OTA) allows DOD, using the authority found in 10 U.S.C. 2371, to enter into transactions with private organizations for basic, applied, and advanced research projects. OTA, in practice, is often defined in the negative: it is not a contract, grant, or cooperative agreement, and its advantages come mostly from exempting OTA transactions from certain procurement statutes and acquisition regulations.

The FY2016 NDAA expanded DOD's ability to use Other Transaction Authority for certain prototype programs, including making some authorities permanent. Subtitle G of Title VIII of the FY2018 NDAA—Provisions Relating to Other Transaction Authority and Prototyping—contains eight sections aimed at expanding and improving the use of OTA.14

Reports, Advisory Panels, and Pilot Programs

The FY2016 NDAA required numerous reports and chartered efforts to explore ways to improve defense acquisition. The most comprehensive such effort was the establishment of the Advisory Panel on Streamlining and Codifying Acquisition Regulations (knows as the 809 Panel after the section of the NDAA establishing the group). The 809 Panel was tasked with finding ways to streamline and improve the defense acquisition process. The independent panel has two years to develop recommendations for changes in the regulation and associated statute to achieve those ends, and must report the recommendations to the Secretary of Defense and to Congress.15

The FY2016 NDAA also required

- each Service Chief to submit a report on linking and streamlining the requirements, budget, and acquisition processes;16 and

- the Secretary of Defense and Joint Chiefs of Staff to review the requirement, budgeting, and acquisition processes, in part to determine the "advisability of providing a time-based or phased distinction between capabilities needed to be deployed urgently, within 2 years, within 5 years, and longer than 5 years."17

The FY2018 NDAA established a three-year pilot program requiring certain companies filing a Government Accountability Office (GAO) bid protest to pay DOD processing costs for the protest when GAO issues an opinion that denies all elements of the protest. The pilot program would begin two years from enactment of the bill.18

Types of Contracts, Contract Audits, and Source Selection Criteria

A micro-purchase is an acquisition of supplies or services using simplified acquisition procedures, the total amount of which does not exceed the micro-purchase threshold.19 The FY2017 NDAA raised DOD's micro-purchase from $3,000 to $5,000. The FY2018 NDAA raised the micro-purchase threshold for the rest of the federal government to $10,000, thus establishing a different threshold for DOD vis-à-vis other federal agencies.

A simplified acquisition is a streamlined method for making purchases of supplies or services. The simplified acquisition threshold delineates what types of purchases can use this streamlined method.20 The FY2018 NDAA also increased the simplified acquisition threshold from $100,000 to $250,000.

The FY2017 NDAA clarified Congress's desire to see DOD increase its use of

- 1. fixed price contracting, (requiring a regulation establishing a preference for such contracts,21 and generally requiring fixed-price contracts for foreign military sales);22 and

- 2. performance-based contract payments.23

The FY2017 NDAA also restricted the use of lowest price technically acceptable (LPTA) source selection criteria to certain circumstances, and specifically calls for avoiding using LPTA for IT and related services, personal protective equipment, and knowledge-based services.24 LPTA is a source selection process where the government determines that the lowest price is the determining factor for award as long as the bidder meets the technical requirements of the solicitation.25 LPTA is appropriate only when the government "expects" it can achieve best value from selecting the proposal that is technically acceptable and offers the lowest evaluated price.26

The FY2018 NDAA required DOD to adhere to commercial standards for risk and materiality when auditing costs incurred under flexibly priced contracts and requires the use of qualified private auditors to ensure the auditing needs of DOD are met,27 and raising the threshold (as well as making other modifications) to required submissions of certified cost and pricing data.28

Major Defense Acquisition Programs

The FY2017 NDAA required major defense acquisition programs (MDAPs) to be designed and developed using "a modular open system architecture approach to enable incremental development and enhance competition, innovation, and interoperability."29 The open architecture requirements extend to major system interfaces and standards for use in major system platforms. The act also generally establishes the authority to conduct and establish funding for prototype projects when there is a high-priority warfighter need due to a capability gap, there is an opportunity to integrate new components into a major weapon system based on commercial technology, the technology is expected to be mature enough to prototype within three years, and there is an opportunity to reduce sustainment costs.30

In an effort to gain visibility into MDAPs and rein in cost growth, the FY2017 NDAA requires the Secretary of Defense to assign program cost and fielding targets to MDAPs before funds are obligated for development.31 It also requires that after each milestone decision, the milestone decision authority provide Congress with an "acquisition scorecard" that includes estimated cost, schedule, and technology risk information.32

Reflecting congressional concern with the sustainment and total life-cycle costs of MDAPs, the FY2017 NDAA required a number of DOD actions, including initiating a review by an independent entity to determine the extent to which sustainment is considered in acquisition decisions,33 and conducting sustainment reviews of programs five years after initial operational capability.34 The act also repealed chapter 144a of Title 10, which created a separate category of acquisition for major automated information systems (§846).

The FY2018 NDAA also contained a number of provisions relating to MDAPs, including a provision excluding defense business systems and major automated information systems from the definition of an MDAP;35 and one prohibiting the use of an LPTA source selection process for development contracts. Other sections would add new requirements aimed at emphasizing reliability and maintainability in MDAPs,36 and focus on test and evaluation plans and data analysis.37

Commercial Items

In the FY2016 NDAA, Subtitle E, Provisions Relating to Commercial Items, required the establishment of a centralized office to oversee commercial item determinations and authorizes a contracting officer to use a prior DOD commercial item determination to serve as the basis for such determinations for subsequent purchases of the same item.38 The act requires that prices previously paid by the government be considered when establishing price reasonableness.39 The act also contained sections aimed at reinforcing the existing statutory preference for buying commercial.40

Building on the FY2016 NDAA, the FY2017 NDAA included 10 provisions relating to commercial items, including requiring market research when determining price reasonableness, and encouraging and simplifying commercial acquisitions.41 The FY2018 NDAA further continued the trend to encourage and expand commercial items authorities. The FY2018 NDAA contained five sections relating to commercial items, including a requirement that GSA contract with multiple commercial online marketplaces and permit agencies to purchase commercial products from these marketplaces.42 Other sections clarify the definition of commercial items and commercial item determinations.43

Data Rights and Intellectual Property

Rights to technical data developed in relation to government contracts have been a long-standing subject of debate between contractors and the government. The FY2016 NDAA set up an advisory panel to submit recommendations on amending regulations governing technical data in MDAPs.44

The FY2017 NDAA made a number of amendments to technical data rights, including giving DOD more authority to negotiate for data rights, and, in the case of interfaces developed exclusively at private expense, to require negotiations to determine the appropriate compensation for the technical data.45

The FY2018 NDAA required DOD to develop policy on the acquisition or licensing of intellectual property and establish a cadre of experts to assist in managing and acquiring intellectual property rights.46

Service Contracting

The FY2017 NDAA limited the amount of funds allowable for staff augmentation contracts within OSD and the military department headquarters for FY2017 and FY2018.47 The FY2018 NDAA addressed contracts for services, including provisions aimed at improving data collection and analysis for contracts for services;48 creating standard guidelines for evaluating requirements for such contracts;49 and establishing a pilot program granting DOD authority to enter into up to five multiyear contracts for services, with each contract lasting for up to 15 years instead of the current limit of 5 years.50

Acquisition Workforce

The FY2016-2018 NDAAs contained 17 provisions relating to the acquisition workforce. The FY2016 NDAA modified the Defense Acquisition Workforce Development Fund (DAWDF),51 required training on how to conduct market research,52 created a dual career track for acquisition and operational specialties,53 and clarified tenure requirements for program managers for MDAPs.54

The FY2017 NDAA expanded the use of DAWDF and made other adjustments to the fund55 and authorizes the position of senior military acquisition advisor, which is filled by presidential appointment, with the advice and consent of the Senate.56

The FY2018 NDAA required the implementation of a program manager development program,57 modifies the Secretary of Defense's authority to adjust DAWDF,58 and extends and expands the Acquisition Demonstration project pilot.59

The Changing Roles of the Chiefs and OSD in Acquisition

Historically, the military services were responsible for virtually all aspects of acquisition and OSD played a limited role. In the early 1980s a number of major defense acquisition programs experienced dramatic cost overruns that increased the defense budget by billions of dollars but resulted in the production of the same number of, or in some cases fewer, weapons than originally planned. In 1985, President Ronald Reagan established the President's Blue Ribbon Commission on Defense Management, chaired by former Deputy Secretary of Defense David Packard.

In 1986, the commission issued a final report that contained far-reaching recommendations "intended to assist the Executive and Legislative Branches as well as industry in implementing a broad range of needed reforms."60 The commission's work, and the recommendations found in the final report, led to the ultimate establishment of the office of the USD (AT&L).

Creation of USD (AT&L)

One of the recommendations of the Packard Commission was to create the position of Under Secretary of Defense (Acquisition) to "set overall policy for procurement and research and development (R&D), supervise the performance of the entire acquisition system, and establish policy for administrative oversight and auditing of defense contractors."61

The report stated that the motivation for establishing this position was as follows:

Responsibility for acquisition policy has become fragmented. There is today no single senior official in the Office of the Secretary of Defense working full-time to provide overall supervision of the acquisition system.... In the absence of such a senior OSD official, policy responsibility has tended to devolve to the Services, where at times it has been exercised without the necessary coordination and uniformity. Worse still, authority for executing acquisition programs—and accountability for their results—has become vastly diluted.62

Later that year, Congress established the position of Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition63 (renamed the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Technology in the FY1994 NDAA64 and finally the Under Secretary of Defense [AT&L] in the FY2000 NDAA).65 The Goldwater-Nichols Act further consolidated centralized civilian control over acquisitions within OSD, as did other acts enacted in subsequent years. Even with these changes, the service Chiefs retained influence over acquisitions. As GAO stated in 2014 (prior to the FY2016 NDAA):

Existing policies and processes for planning and executing acquisition programs provide multiple opportunities for the service chiefs to be involved in managing acquisition programs and to help ensure programs meet cost, schedule, and performance targets. Whether the service chiefs are actively involved and choose to influence programs is not clear.66

Shifting Authority Back to the Chiefs and the Services

In 2015, a number of analysts and officials, including former Deputy Secretary of Defense John Hamre (currently CEO of the Center for Strategic and International Studies), and then-Army Chief of Staff General Ray Odierno, called for reversing course and giving the services and the Chiefs more authority over acquisitions. John Hamre argued the following:

No one assumes that the service chiefs are not responsible for weapon systems; they play a central role in establishing military requirements and resourcing decisions. Moreover, every time a program gets in trouble, it is the service chief who is called up for a grilling before Congress.

Yet the service chief is not in the acquisition chain of command. We get in trouble in the Defense Department when authority and accountability are fractured. Giving the service chiefs responsibility for requirements and budgets but not acquisition makes no sense.67

Many other analysts took the opposite view, and the Obama Administration strongly objected to such changes, arguing that if enacted, they would reduce the Secretary of Defense's ability to guard against unwarranted cost optimism and prevent excessive risk-taking.68 The Senate initiated a number of provisions that enhanced the role of the Chiefs and the military services. Commenting on the provisions in the Senate version of the NDAA, the Statement of Administration Policy stated that if enacted, the Senate provisions would

significantly reduce the Secretary of Defense's ability—through the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition, Technology and Logistics USD (AT&L)—to guard against unwarranted optimism in program planning and budget formulation, and prevent excessive risk taking during execution—all of which is essential to avoiding overruns and costly delays.

Much of the substance of the provisions in the Senate bill was incorporated into the FY2016 NDAA. The FY2017 NDAA refined the swing back to the services and also initiated a large-scale reorganization of the office of the USD (AT&L), a reorganization that continued in the FY2018 NDAA.

The FY2016 NDAA

According to the joint explanatory statement accompanying the FY2016 NDAA, Section 802 was intended to "enhance the role of Chiefs of Staff in the defense acquisition process."69 The section opens with the policy statement that the purpose of defense acquisition is to "meet the needs of its customers in the most cost-effective manner practicable." The customer is defined as the military service with primary responsibility for fielding the system or systems acquired, represented by "the Secretary of the military department concerned and the Chief of the armed force concerned" with regard to major defense acquisition programs.

Section 802 goes on to amend 10 U.S.C. 2547(a) by assigning the Chiefs the responsibility to assist the Secretary of the military department in making

- decisions regarding balancing resources and priorities, and associated trade-offs among cost, schedule, technical feasibility, and performance on major defense acquisition; and

- the management of career paths in acquisition for military personnel.70

Section 802 also required

- the Joint Requirements Oversight Council to "seek, and strongly consider, the views of the Chiefs of Staff of the armed forces" and

- for major defense acquisition programs, the Chiefs to advise the decision authority for Milestones A and B on cost, schedule, technical feasibility, and performance trade-offs.

Section 825 requires that, generally, the service acquisition executive be the milestone decision authority for major defense acquisition programs.71

A number of other sections in the NDAA aim at strengthening the role of the services in acquisitions, including

- requiring the Milestone A and Milestone B decision authority to get concurrence on the cost, schedule, technical feasibility, and performance trade-offs of a program from the relevant service Secretary and Chief (§§823-824);

- requiring Configuration Steering Boards for major programs to ensure that the relevant Chief, in consultation with the service Secretary, "approves of any proposed changes that could have an adverse effect on program cost or schedule'' (§830); and

- giving the Chiefs a role in establishing policies on the development, assignment, and employment of the acquisition workforce (§842). This section does not include the future USD (A&S) in the chain of command in establishing such policies.72

The FY2017 NDAA and the Split of USD (AT&L) Responsibilities

The FY2017 NDAA does not directly shift more acquisition authority to the military services. However, some of the sections in the bill could have the effect of adjusting acquisition authority in favor of the services.

Section 901, while not directly affecting the balance of authority between OSD and the services, significantly affects OSD's role in defense acquisition. Most notably, the section breaks up AT&L into the USD (Research and Engineering) and USD (Acquisition and Sustainment, A&S). According to the conference report,

[t]hree broad priorities framed the conference discussions: (1) elevate the mission of advancing technology and innovation within the Department; (2) foster distinct technology and acquisition cultures to better deliver superior capabilities for the armed forces; and (3) provide greater oversight and management of the Department's Fourth Estate.73

Section 807 of the FY2017 NDAA requires that before funds are obligated for technology development, systems development, or production of an MDAP, the Secretary of Defense must establish goals for the milestone decision authority, including for cost, schedule, and technology maturation. Notably, the responsibility to establish these goals "may be delegated only to the Deputy Secretary of Defense."74 Given that the decision authority is generally the service acquisition authority, and the requirement to set goals cannot be delegated below the Deputy Secretary of Defense, this section does not include the future USD (A&S) in the chain of command, potentially eroding the influence of the USD (A&S).

A number of other sections in the NDAA appear to strengthen the role of the services in acquisitions, including the following:

- Requiring the Director of Operational Test and Evaluation to submit the annual report to the Secretaries of the military departments (§845). Previously, the annual report was submitted to the Secretary of Defense, USD (AT&L), and Congress.

- Granting the service acquisition authority the ability to waive tenure requirements in certain circumstances (§862). Previously, only the Secretary of Defense could do so.

- Authorizing the military departments to establish service-specific funds for acquisition programs using certain rapid fielding and prototyping authorities (§897).

The FY2018 NDAA

The FY2018 NDAA included a number of provisions conforming and clarifying the roles of USD (A&S).75 As it relates to MDAPs, the act also amended 10 U.S.C. 2547(b), requiring that the relevant service chief concur with

- the need for a material solution (as identified in the Material Development Decision Review);

- the cost, schedule, technical feasibility, and performance trade-offs before Milestone A is approved;

- the cost, schedule, technical feasibility, and performance trade-offs before Milestone B is approved; and

- the requirements, cost, and fielding timeline before Milestone C is approved.

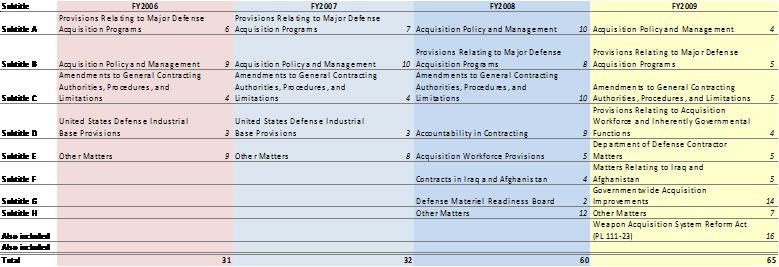

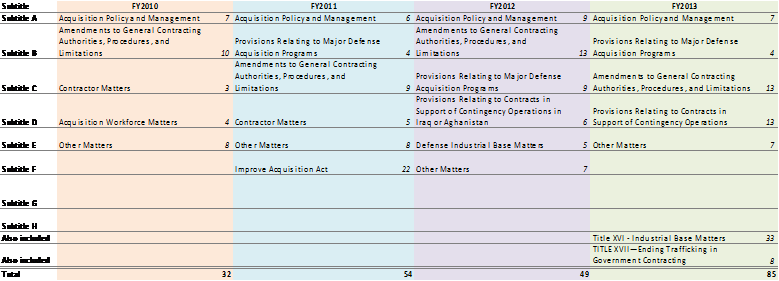

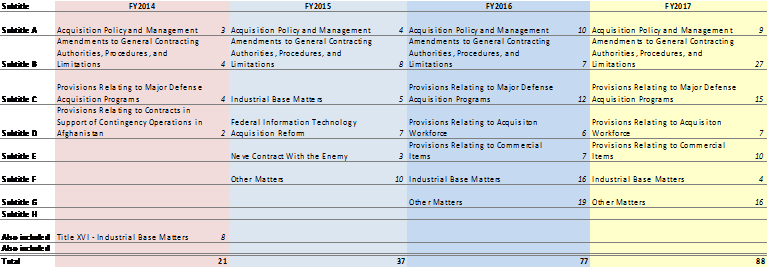

Appendix. Title VIII Provisions in the FY2006-FY2018 NDAAs

|

Figure A-1. Title VIII Provisions in the FY2006-FY2018 NDAAs |

|

|

|

|

|

Source: CRS analysis of the FY2006-FY2018 National Defense Authorization Acts and the Weapon System Acquisition Reform Act (P.L. 111-23). Notes: The Weapon Acquisition System Reform Act (P.L. 111-23) is included in the FY2009 count because the act was focused exclusively on defense acquisition. In some years, the NDAA also contains titles specifically dedicated to aspects of acquisition, such as Title XVII of the FY2018 NDAA, entitled Small Business Procurement and Industrial Base Matters. Such acquisition-specific titles are included in the count and specifically identified. In some years, titles within the NDAA that are not specifically focused on acquisition contain sections related to acquisitions. Such instances are excluded from this analysis. |