Introduction

This report provides background information and potential oversight issues for Congress on the Gerald R. Ford (CVN-78) class aircraft carrier program. The Navy's proposed FY2018 budget requested a total of $4,461.8 million in procurement funding for the program. Congress's decisions on the CVN-78 program could substantially affect Navy capabilities and funding requirements and the shipbuilding industrial base.

For an overview of the strategic and budgetary context in which the CVN-78 class program and other Navy shipbuilding programs may be considered, see CRS Report RL32665, Navy Force Structure and Shipbuilding Plans: Background and Issues for Congress, by [author name scrubbed].1

Background

The Navy's Aircraft Carrier Force

The Navy's current aircraft carrier force consists of 11 nuclear-powered ships, including 10 Nimitz-class ships (CVNs 68 through 77) that entered service between 1975 and 2009, and one Gerald R. Ford (CVN-78) class ship that was delivered to the Navy on May 31, 2017, and commissioned into service on July 22, 2017.2 The commissioning into service of CVN-78 ended a period during which the carrier force had declined to 10 ships that began on December 1, 2012, with the inactivation of the one-of-a-kind nuclear-powered aircraft carrier Enterprise (CVN-65), a ship that entered service in 1961.

Statutory Requirement to Maintain Not Less Than 11 Carriers

Origin of Requirement

10 U.S.C. 5062(b) requires the Navy to maintain a force of not less than 11 operational aircraft carriers. The requirement for the Navy to maintain not less than a certain number of operational aircraft carriers was established by Section 126 of the FY2006 National Defense Authorization Act (H.R. 1815/P.L. 109-163 of January 6, 2006), which set the number at 12 carriers. The requirement was changed from 12 carriers to 11 carriers by Section 1011(a) of the FY2007 John Warner National Defense Authorization Act (H.R. 5122/P.L. 109-364 of October 17, 2006).

Waiver for Period Between CVN-65 and CVN-78

As mentioned above, the carrier force dropped from 11 ships to 10 ships between December 1, 2017, when Enterprise (CVN-65) was inactivated, and July 22, 2017, when CVN-78 was commissioned into service. Anticipating the gap between the inactivation of CVN-65 and the commissioning of CVN-78, the Navy asked Congress for a temporary waiver of 10 U.S.C. 5062(b) to accommodate the period between the two events. Section 1023 of the FY2010 National Defense Authorization Act (H.R. 2647/P.L. 111-84 of October 28, 2009) authorized the waiver, permitting the Navy to have 10 operational carriers between the inactivation of CVN-65 and the commissioning of CVN-78.

Statutory Requirement to Maintain Not Less Than Nine Carrier Air Wings

In addition to the above-discussed statutory requirement for maintaining not less than 11 operational aircraft carriers, 10 U.S.C. 5062(e) states:

The Secretary of the Navy shall ensure that-

(1) the Navy maintains a minimum of 9 carrier air wings until the earlier of-

(A) the date on which additional operationally deployable aircraft carriers can fully support a 10th carrier air wing; or

(B) October 1, 2025;

(2) after the earlier of the two dates referred to in subparagraphs (A) and (B) of paragraph (1), the Navy maintains a minimum of 10 carrier air wings; and

(3) for each such carrier air wing, the Navy maintains a dedicated and fully staffed headquarters.3

New Navy Force-Level Goal of 12 Carriers

In December 2016, the Navy released a new force-level goal for achieving and maintaining a fleet of 355 ships, including 12 aircraft carriers4—one more than the minimum of 11 carriers required by 10 U.S.C. 5062(b). This was the first Navy force-level goal to call for 12 (rather than 11) carriers since a 2002-2004 Navy force-level goal for a fleet of 375 ships.5

Aircraft Carrier Procurement Rates

Procurement Rates and Resulting Dates for Achieving 12-Carrier Force

Given the time needed to build a carrier and the projected retirement dates of existing carriers, increasing the carrier force from 11 ships to 12 ships on a sustained basis would take a number of years:

- Increasing aircraft carrier procurement from the currently planned five-year centers to three-year centers—that is, increasing aircraft carrier procurement from the currently planned rate of one ship every five years (i.e., FY2018, FY2023, and so on) to a rate of one ship every three years (i.e., FY2018, FY2021, and so on)—would achieve a 12-carrier force on a sustained basis by about 2030.

- Increasing aircraft carrier procurement to 3.5-year centers (i.e., a combination of three- and four-year centers) would achieve a 12-carrier force on a sustained basis by about 2034.

- Increasing aircraft carrier procurement to four-year centers would achieve a 12-carrier force on a sustained basis by about 2063—almost 30 years later than under 3.5-year centers.6

Avoiding a Decline from 11 Carriers to 10

If carriers continue to be procured on five-year centers, the carrier force would drop from 11 ships to 10 ships starting in FY2040.7 Procuring carriers on four-year centers would maintain the carrier force at 11 ships through the end of the 30-year period (FY2017-FY2046) covered in the Navy's FY2017 30-year shipbuilding plan, and thus prevent the force from dropping to 10 ships starting in 2040. (And as discussed above, procuring carriers on four-year centers would eventually—by 2063—increase the force to 12 ships on a sustained basis.)

Section 127 of the FY2017 National Defense Authorization Act (S. 2943/P.L. 114-328 of December 23, 2016) states:

SEC. 127. Sense of Congress on aircraft carrier procurement schedules.

(a) Findings.—Congress finds the following:

(1) In the Congressional Budget Office report titled "An Analysis of the Navy's Fiscal Year 2016 Shipbuilding Plan", the Office stated as follows: "To prevent the carrier force from declining to 10 ships in the 2040s, 1 short of its inventory goal of 11, the Navy could accelerate purchases after 2018 to 1 every four years, rather than 1 every five years".

(2) In a report submitted to Congress on March 17, 2015, the Secretary of the Navy indicated the Department of the Navy has a requirement of 11 aircraft carriers.

(b) Sense of congress.—It is the sense of Congress that—

(1) the plan of the Department of the Navy to schedule the procurement of one aircraft carrier every five years will reduce the overall aircraft carrier inventory to 10 aircraft carriers, a level insufficient to meet peacetime and war plan requirements; and

(2) to accommodate the required aircraft carrier force structure, the Department of the Navy should—

(A) begin to program construction for the next aircraft carrier to be built after the U.S.S. Enterprise (CVN–80) in fiscal year 2022; and

(B) program the required advance procurement activities to accommodate the construction of such carrier.

Funding Requirements and Unit Costs

Increasing aircraft carrier procurement from five-year centers to four-, 3.5-, or three-year centers would increase average annual funding requirements for aircraft carrier procurement while reducing aircraft carrier unit procurement costs due to greater spreading of fixed overhead costs and improved production learning curve benefits at the shipyard and component manufacturers.

Funding and Procuring Aircraft Carriers

Some Key Terms

The Navy procures a ship (i.e., orders the ship) by awarding a full-ship construction contract to the firm building the ship.

Part of a ship's procurement cost might be provided through advance procurement (AP) funding. AP funding is funding provided in one or more years prior to (i.e., in advance of) a ship's year of procurement. AP funding is used to pay for long-leadtime components that must be ordered ahead of time to ensure that they will be ready in time for their scheduled installation into the ship. AP funding is also used to pay for the design costs for a new class of ship. These design costs, known more formally as detailed design/non-recurring engineering (DD/NRE) costs, are traditionally incorporated into the procurement cost of the lead ship in a new class of ships.

Fully funding a ship means funding the entire procurement cost of the ship. If a ship has received AP funding, then fully funding the ship means paying for the remaining portion of the ship's procurement cost.

The full funding policy is a Department of Defense (DOD) policy that normally requires items acquired through the procurement title of the annual DOD appropriations act to be fully funded in the year they are procured. In recent years, Congress has authorized DOD to use incremental funding for procuring certain Navy ships, most notably aircraft carriers. Under incremental funding, some of the funding needed to fully fund a ship is provided in one or more years after the year in which the ship is procured.8

Incremental Funding Authority for Aircraft Carriers

Section 121 of the FY2007 John Warner National Defense Authorization Act (H.R. 5122/P.L. 109-364 of October 17, 2006) granted the Navy the authority to use four-year incremental funding for CVNs 78, 79, and 80. Under this authority, the Navy could fully fund each of these ships over a four-year period that includes the ship's year of procurement and three subsequent years.

Section 124 of the FY2012 National Defense Authorization Act (H.R. 1540/P.L. 112-81 of December 31, 2011) amended Section 121 of P.L. 109-364 to grant the Navy the authority to use five-year incremental funding for CVNs 78, 79, and 80. Since CVN-78 was fully funded in FY2008-FY2011, the provision in practice applied to CVNs 79 and 80.

Section 121 of the FY2013 National Defense Authorization Act (H.R. 4310/P.L. 112-239 of January 2, 2013) amended Section 121 of P.L. 109-364 to grant the Navy the authority to use six-year incremental funding for CVNs 78, 79, and 80. Since CVN-78 was fully funded in FY2008-FY2011, the provision in practice applies to CVNs 79 and 80.

Aircraft Carrier Construction Industrial Base

All U.S. aircraft carriers procured since FY1958 have been built by Newport News Shipbuilding (NNS), of Newport News, VA, a shipyard that is part of Huntington Ingalls Industries (HII). HII/NNS is the only U.S. shipyard that can build large-deck, nuclear-powered aircraft carriers. The aircraft carrier construction industrial base also includes hundreds of subcontractors and suppliers in various states.

Gerald R. Ford (CVN-78) Class Program

The Gerald R. Ford (CVN-78) class carrier design (Figure 1 and Figure 2) is the successor to the Nimitz-class carrier design.9

|

|

Source: Navy photograph dated April 8, 2017, accessed October 3, 2017, at: http://www.navy.mil/view_image.asp?id=234835 |

The Ford-class design uses the basic Nimitz-class hull form but incorporates several improvements, including features permitting the ship to generate more aircraft sorties per day, more electrical power for supporting ship systems, and features permitting the ship to be operated by several hundred fewer sailors than a Nimitz-class ship, reducing 50-year life-cycle operating and support (O&S) costs for each ship by about $4 billion compared to the Nimitz-class design, the Navy estimates. Navy plans call for procuring at least four Ford-class carriers—CVN-78, CVN-79, CVN-80, and CVN-81.

|

|

Source: Navy photograph dated April 8, 2017, accessed October 3, 2017, at: http://www.navy.mil/view_image.asp?id=234833 |

CVN-78

CVN-78, which was named for President Gerald R. Ford in 2007,10 was procured in FY2008. The Navy's proposed FY2018 budget estimates the ship's procurement cost at $12,907.0 million (i.e., about $12.9 billion) in then-year dollars. The ship received advance procurement funding in FY2001-FY2007 and was fully funded in FY2008-FY2011 using congressionally authorized four-year incremental funding. To help cover cost growth on the ship, the ship received an additional $1,374.9 million in FY2014-FY2016 cost-to-complete procurement funding. The Navy's proposed FY2018 budget requests $20 million in additional cost-to-complete procurement funding. The ship was delivered to the Navy on May 31, 2017, and was commissioned into service on July 22, 2017.

CVN-79

CVN-79, which was named for President John F. Kennedy on May 29, 2011,11 was procured in FY2013. The Navy's proposed FY2018 budget estimates the ship's procurement cost at $11,377.4 million (i.e., about $11.4 billion) in then-year dollars. The ship received advance procurement funding in FY2007-FY2012, and the Navy plans to fully fund the ship in FY2013-FY2018 using congressionally authorized six-year incremental funding. The Navy's proposed FY2018 budget requests $2,561.1 million in procurement funding for the ship. The ship is scheduled for delivery to the Navy in September 2024.

CVN-80

CVN-80, which was named Enterprise on December 1, 2012,12 is scheduled to be procured in FY2018. The Navy's proposed FY2018 budget estimates the ship's procurement cost at $12,997.6 million (i.e., about $13.0 billion) in then-year dollars. The ship received AP funding in FY2016 and FY2017, and the Navy plans to fully fund the ship in FY2018-FY2023 using congressionally authorized six-year incremental funding. The Navy's proposed FY2018 budget requests $1,880.7 million in procurement funding for the ship. The ship is scheduled for delivery to the Navy in September 2027.

CVN-81

CVN-81 is scheduled under the Navy's FY2017 30-year shipbuilding plan to be procured in FY2023. Under that schedule, the Navy would use AP funding for the ship in FY2021 and FY2022, and then fully fund the ship in FY2023-FY2028 using congressionally authorized six-year incremental funding. The Navy's FY2018 budget submission programs the initial increment of AP funding for the ship in FY2021.

Program Procurement Funding

Table 1 shows procurement funding for CVNs 78, 79, 80, and 81 through FY2021 as shown in the Navy's FY2018 budget submission.

Table 1. Procurement Funding for CVNs 78, 79, 80, and 81 Through FY2023

(Millions of then-year dollars, rounded to nearest tenth)

|

FY |

CVN-78 |

CVN-79 |

CVN-80 |

CVN-81 |

Total |

|

FY01 |

21.7 (AP) |

0 |

0 |

0 |

21.7 |

|

FY02 |

135.3 (AP) |

0 |

0 |

0 |

135.3 |

|

FY03 |

395.5 (AP) |

0 |

0 |

0 |

395.5 |

|

FY04 |

1,162.9 (AP) |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1,162.9 |

|

FY05 |

623.1 (AP) |

0 |

0 |

0 |

623.1 |

|

FY06 |

618.9 (AP) |

0 |

0 |

0 |

618.9 |

|

FY07 |

735.8 (AP) |

52.8 (AP) |

0 |

0 |

788.6 |

|

FY08 |

2,685.0 (FF) |

123.5 (AP) |

0 |

0 |

2,808.5 |

|

FY09 |

2,684.6 (FF) |

1,210.6 (AP) |

0 |

0 |

3,895.2 |

|

FY10 |

737.0 (FF) |

482.9 (AP) |

0 |

0 |

1,219.9 |

|

FY11 |

1,712.5 (FF) |

902.5 (AP) |

0 |

0 |

2,615.0 |

|

FY12 |

0 |

554.8 (AP) |

0 |

0 |

554.8 |

|

FY13 |

0 |

491.0 (FF) |

0 |

0 |

491.0 |

|

FY14 |

588.1 (CC) |

917.6 (FF) |

0 |

0 |

1,505.7 |

|

FY15 |

663.0 (CC) |

1,219.4 (FF) |

0 |

0 |

1,882.4 |

|

FY16 |

123.8 (CC) |

1,569.6 (FF) |

862.4 (AP) |

0 |

2,555.8 |

|

FY17 |

0 |

1,291.8 (FF) |

1,370.8 (AP) |

0 |

2,662.6 |

|

FY18 (requested) |

20.0 (CC) |

2,561.1 (FF) |

1,880.7 (FF) |

0 |

4,461.8 |

|

FY19 (programmed) |

0 |

0 |

1,577.0 (FF) |

0 |

1,577.0 |

|

FY20 (programmed) |

0 |

0 |

2,234.6 (FF) |

0 |

2,234.6 |

|

FY21 (programmed) |

0 |

0 |

1,961.9 (FF) |

1,004.2 (AP) |

2,966.0 |

|

FY22 (programmed) |

0 |

0 |

765.8 (FF) |

1,586.1 (AP) |

2,351.9 |

|

FY23 (projected) |

0 |

0 |

2,344.4 (FF) |

n/a (FF) |

n/a |

|

Total |

12,907.0 |

11,377.4 |

12,997.6 |

n/a |

n/a |

Source: Table prepared by CRS based on FY2018 Navy budget submission.

Notes: Figures may not add due to rounding. "AP" is advance procurement funding; "FF" is full funding; "CC" is cost to complete funding (i.e., funding to cover cost growth).

Changes in Estimated Unit Procurement Costs Since FY2008 Budget

Table 2 shows changes in the estimated procurement costs of CVNs 78, 79, 80, and 81 since the budget submission for FY2008—the year of procurement for CVN-78.

Table 2. Changes in Estimated Procurement Costs of CVNs 78, 79, 80, and 81

(As shown in FY2008-FY2018 budgets, in millions of then-year dollars)

|

Budget |

CVN-78 |

CVN-79 |

CVN-80 |

CVN-81 |

||||

|

Est. proc. cost |

Scheduled FY of proc. |

Est. proc. cost |

Scheduled FY of proc. |

Est. proc. cost |

Scheduled FY of proc. |

Est. proc. cost |

Scheduled FY of proc. |

|

|

FY08 |

10,488.9 |

FY08 |

9,192.0 |

FY12 |

10,716.8 |

FY16 |

n/a |

FY21 |

|

FY09 |

10,457.9 |

FY08 |

9,191.6 |

FY12 |

10,716.8 |

FY16 |

n/a |

FY21 |

|

FY10 |

10,845.8 |

FY08 |

n/a |

FY13 |

n/a |

FY18 |

n/a |

FY23 |

|

FY11 |

11,531.0 |

FY08 |

10,413.1 |

FY13 |

13,577.0 |

FY18 |

n/a |

FY23 |

|

FY12 |

11,531.0 |

FY08 |

10,253.0 |

FY13 |

13,494.9 |

FY18 |

n/a |

FY23 |

|

FY13 |

12,323.2 |

FY08 |

11,411.0 |

FY13 |

13,874.2 |

FY180 |

n/a |

FY23 |

|

FY14 |

12,829.3 |

FY08 |

11,338.4 |

FY13 |

13,874.2 |

FY18 |

n/a |

FY23 |

|

FY15 |

12,887.2 |

FY08 |

11,498.0 |

FY13 |

13,874.2 |

FY18 |

n/a |

FY23 |

|

FY16 |

12,887.0 |

FY08 |

11,347.6 |

FY13 |

13,472.0 |

FY18 |

n/a |

FY23 |

|

FY17 |

12,887.0 |

FY08 |

11,398.0 |

FY13 |

12,900.0 |

FY18 |

n/a |

FY23 |

|

FY18 |

12,907.0 |

FY08 |

11,377.4 |

FY13 |

12,997.6 |

FY18 |

n/a |

FY23 |

|

Annual % change |

||||||||

|

FY08 to FY09 |

-0.3 |

0% |

0% |

n/a |

||||

|

FY09 to FY10 |

+3.7 |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

||||

|

FY10 to FY11 |

+6.3 |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

||||

|

FY11 to FY12 |

0% |

-1.5% |

-0.1% |

n/a |

||||

|

FY12 to FY13 |

+6.9% |

+11.3% |

+2.8% |

n/a |

||||

|

FY13 to FY14 |

+4.1% |

-0.6% |

0% |

n/a |

||||

|

FY14 to FY15 |

+0.5% |

+1.4% |

0% |

n/a |

||||

|

FY15 to FY16 |

0% |

-1.3% |

-2.9% |

n/a |

||||

|

FY16 to FY17 |

0% |

+0.4% |

-4.2% |

n/a |

||||

|

FY17 to FY18 |

+0.2% |

-0.2% |

+0.7% |

n/a |

||||

|

Cumulative % change through FY17 |

||||||||

|

Since FY08 (CVN-78 year of proc.) |

+23.1% |

+23.8% |

+21.3% |

n/a |

||||

|

Since FY13 (CVN-79 year of proc.) |

+4.7% |

-0.3% |

-6.3% |

n/a |

||||

Source: Table prepared by CRS based on FY2008-FY2018 Navy budget submissions. n/a means not available.

Notes: (1) The FY2010 budget submission did not show estimated procurement costs for CVNs 79 and 80. (2) The FY2010 budget submission did not show scheduled years of procurement for CVNs 79 and 80; the dates shown here for the FY2010 budget submission are inferred from the shift to five-year intervals for procuring carriers that was announced by Secretary of Defense Gates in his April 6, 2009, news conference regarding recommendations for the FY2010 defense budget. (3) Although the FY2013 budget did not change the scheduled years of procurement for CVN-79 and CVN-80 compared to what they were under the FY2012 budget, it lengthened the construction period for each ship by two years (i.e., each ship was scheduled to be delivered two years later than under the FY2012 budget).

Program Procurement Cost Cap

Section 122 of the FY2007 John Warner National Defense Authorization Act (H.R. 5122/P.L. 109-364 of October 17, 2006) established a procurement cost cap for CVN-78 of $10.5 billion, plus adjustments for inflation and other factors, and a procurement cost cap for subsequent Ford-class carriers of $8.1 billion each, plus adjustments for inflation and other factors. The conference report (H.Rept. 109-702 of September 29, 2006) on P.L. 109-364 discusses Section 122 on pages 551-552.

Section 121 of the FY2014 National Defense Authorization Act (H.R. 3304/P.L. 113-66 of December 26, 2013) amended the procurement cost cap for the CVN-78 program to provide a revised cap of $12,887.0 million for CVN-78 and a revised cap of $11,498.0 million for each follow-on ship in the program, plus adjustments for inflation and other factors (including an additional factor not included in original cost cap).

Section 122 of the FY2016 National Defense Authorization Act (S. 1356/P.L. 114-92 of November 25, 2015) further amended the cost cap for the CVN-78 program to provide a revised cap of $11,398.0 million for each follow-on ship in the program, plus adjustment for inflation and other factors, and with a new provision stating that, if during construction of CVN–79, the Chief of Naval Operations determines that measures required to complete the ship within the revised cost cap shall result in an unacceptable reduction to the ship's operational capability, the Secretary of the Navy may increase the CVN–79 cost cap by up to $100 million (i.e., to $11.498 billion). If such an action is taken, the Navy is to adhere to the notification requirements specified in the cost cap legislation.

In an August 2, 2017, letter to the congressional defense committees, then-Acting Secretary of the Navy Sean Stackley notified the committees that under subsection (b)(7) of Section 122 of P.L. 114-92 as amended by Section 121 of P.L. 113-66—a subsection allowing increases to the cost cap for CVN-78 for "the amounts of increases or decreases in costs of that ship that are attributable solely to an urgent and unforeseen requirement identified as a result of the shipboard test program"—he had increased the cost cap for CVN-78 by $20 million, to $12,907.0 million.

Issues for Congress for FY2018

FY2018 Funding Request

One issue for Congress for FY2018 is whether to approve, reject, or modify the Navy's FY2018 procurement requests for the CVN-78 program. In assessing this question, Congress could consider various factors, including whether the Navy has accurately priced the work to be funded in FY2018.

Impact of CR on Execution of FY2018 Funding

Another potential issue for Congress concerns the impact of using a continuing resolution (CR) to fund DOD for the first few months of FY2018.13 Division D of the Continuing Appropriations Act, 2018 and Supplemental Appropriations for Disaster Relief Requirements Act, 2017 (H.R. 601/P.L. 115-56 of September 8, 2017) is the Continuing Appropriations Act, 2018, a CR that funds government operations through December 8, 2017. Consistent with CRs that have funded DOD operations for parts of prior fiscal years, DOD funding under this CR is based on funding levels in the previous year's DOD appropriations act—in this case, the FY2017 DOD Appropriations Act (Division C of the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2017 [H.R. 244/P.L. 115-31 of May 5, 2017]). Also consistent with CRs that have funded DOD operations for parts of prior fiscal years, this CR prohibits new starts, year-to-year quantity increases, and the initiation of multiyear procurements utilizing advance procurement funding for economic order quantity (EOQ) procurement unless specifically appropriated later. Division D of H.R. 601/P.L. 115-56 of September 8, 2017, does not include any anomalies for Department of the Navy acquisition programs.14

A pair of August 3, 2017, tables of CR impacts to FY2018 DOD programs that were reportedly sent by DOD to the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) in August 2017 states that a CR will impact the execution of:

- $20.0 million in cost-to-complete (CTC) procurement funding15 for CVN-78, starting on October 1, 2017;

- $10.9 million in Other Procurement, Navy (OPN) funding for the Advanced Arresting Gear (AAG) used by CVN-78 class carriers, starting on January 1, 2018; and

- about $4,441.8 million in procurement funding for CVN-79 and CVN-80, starting on March 1, 2018.16

Option for Advance Procurement Funding for CVN-81 in FY2018

Another potential issue for Congress for FY2018 is whether to provide advance procurement (AP) funding in FY2018 for the purchase of materials for CVN-81, so as to accelerate the procurement of the ship to a year earlier than FY2023 and/or initiate a combined purchase of materials for CVN-80 and CVN-81 or a block buy contract for the two ships.

Accelerating the procurement of CVN-81 from FY2023 to FY2021 or FY2022 would be consistent with shifting to three- or four-year centers for aircraft carrier procurement. As discussed earlier, shifting to three- or four-year centers for aircraft carrier procurement would be consistent with increasing the size of the aircraft carrier force to an eventual total of 12 ships (or, in the case of four-year centers, at least preventing the force from dropping to 10 ships during the final years of the period covered in the 30-year shipbuilding plan).

Supporters of a combined material purchase or block buy contract for CVN-80 and CVN-81 could argue that it would reduce the procurement costs of the ships by a few or several percent and help stabilize smaller supplier firms in the aircraft carrier construction industrial base by providing an assurance of future work. Skeptics or opponents of a combined material purchase or block buy contract for CVN-80 and CVN-81 could argue that it would create a commitment to procuring CVN-81 years ahead of time, reducing Congress's future flexibility to change plans for procuring CVN-81 in response to changes in the strategic environment or budgetary circumstances. Block buy contracts, which the Navy has used in three other shipbuilding programs, are discussed in greater detail in another CRS report.17

An October 19, 2017, press report states:

The U.S. Navy may soon ask Congress to green light purchasing two new aircraft carriers at once to help cut construction costs for the capital ships after President Donald Trump vowed to pay less for the service's fleet.

Navy Secretary Richard V. Spencer said he asked companies to develop plans to reduce the cost of buying warships. The companies suggested that buying two aircraft carriers at the same time could yield savings, and the proposal is starting to look attractive enough for the Navy to back the plan, Mr. Spencer told the Wall Street Journal....

Mr. Spencer would not say how much savings defense contractors are offering on the carrier deal, but said it could be significant. Getting Congress to commit in advance to an additional carrier could be difficult because it strips lawmaker of some control over funding.

"They are right at the cusp of making it worth heavy, heavy lifting," Mr. Spencer said in an interview with the Wall Street Journal....

For more than a year a group of companies involved in building aircraft carriers have been lobbying Congress to back a multi-ship purchase.

The joint contract would cover production of the USS Enterprise, designated CVN-80, which is due to enter service around 2027, and a follow-on ship, CVN-81, which has not yet been named. The ships would still be built in sequence, but the certainty over future work could allow companies to sign more favorable supplier contracts and invest..18

An August 5, 2016, press report states:

The Navy is formally investigating the possibility of a two-aircraft carrier block buy—lashing procurement of CVN-80 and CVN-81 together across more than a decade—as part of an effort to identify potential options for reducing the total price tag for new Ford-class mega warships, according to the service.

The Navy outlined this potential option, along with others the service is considering to reduce end-costs of new aircraft carrier within mandated cost caps, in a report to Congress delivered on April 22, according to a service spokeswoman.19

A March 18, 2016, press report states:

The Aircraft Carrier Industrial Base Coalition [ACIBC] has asked lawmakers for "design for affordability" research and development dollars to reduce the cost of building carriers and for advance procurement funding for a block buy of CVN-80 and 81 materials.

The organization, and employees of companies from all tiers of the aircraft carrier supply chain, made five requests during a two-day visit to Capitol Hill, which included private meetings with lawmakers and an open-mic breakfast during which a dozen congressmen expressed support for aircraft carriers and the companies that build them....

The dual-ship buy is one of the five ACIBC talking points for this year's event. Coalition chairman Richard Giannini told USNI News at the breakfast that the organization is asking for $293 million to be pulled forward into the Fiscal Year 2017 budget to support advance procurement for both CVN-80, the future Enterprise, and 81.

That will help us to consolidate the buying efforts," said Giannini, who is also president and CEO of Milwaukee Valve Company.

"They're going to start with this first block on the real long lead time stuff, the bigger equipment, and then over the next several years we'll do the same thing with the suppliers that have shorter lead times. And what that will do is save about $400 to $500 million off the cost of the carrier."

The group is also asking for $20 million in research in development money for a "design for affordability" initiative, which aims to find more efficient ways to build the ship. A similar effort for the Virginia-class attack submarine program saw a five-to-one return on investment, he said.20

The possibility of a combined materials purchase for CVN-80 and CVN-81 was discussed at a February 25, 2015, hearing on Department of the Navy acquisition programs before the Seapower and Projection Forces subcommittee of the House Armed Services Committee. At this hearing, the following exchange occurred:

REPRESENATIVE WITTMAN (continuing):

Secretary Stackley, traditionally, as you look at aircraft carrier advice, we've done them in two-ship procurements....21

We've seen with Arleigh Burke-class destroyers as we purchase ships in groups [i.e., under multiyear procurement contracts], we've seen about 15 percent savings when we do that just because of certainties especially for our suppliers for those ships especially aircraft carriers.

Is there any consideration given to grouping advance procurement on CVN 80 and CVN 81...?

SEAN STACKLEY, ASSISTANT SECRETARY OF THE NAVY FOR RESEARCH, DEVELOPMENT, AND ACQUISITION:

Let me start with the advance procurement for CVN 80 and CVN 81. There's strong argument for why that makes great sense. When you're procuring an aircraft carrier about once every five years and you're relying on a very unique industrial base to do that what you don't want to do is go through the start-stop-start-stop cycle over a stretched period of time and that's a big cost impact.

But the challenge is by the same token, the build cycle for our carrier is greater than 10 years. So CVN 79, for example, she started her advance procurement in [FY]2009 and then she will be delivering to the Navy in 2022. So that's a 13-year period.

So when you talk about doubling down and buying material to support two carriers five years apart that have a 13-year build span, you're trying to buy material as much as 18 years ahead of when the carrier went through the fleet.

So it's a—it makes great sense looking at just from the program's perspective on why we want to do that to drive the cost of the carrier down, there's risk associated with things like not necessarily obsolescence but change associated with the carrier because the threat changes and that brings change.

And then the investment that far in advance when the asset actually interests the fleet. As the acquisition guy, I will argue for why we need to do that but getting through -- carrying that argument all the way through to say that we're going to take the [CVN] 80 which is in [FY]2018 ship, the [CVN] 81 which is at [sic:an] [FY]2023 ship, buy material early for that 2023 ship delivering to the Navy in the mid 2030s. That's going to be a hard—it's going to be hard for me to carry the day in terms of our budget process.

WITTMAN:

So we have to have the compelling case for the specific things that from industrial base perspective from a move the needle from a cost perspective justify the combined buys of [CVN] 80 and [CVN] 81 together.

Well, it seems like even if the scale is an issue as far as how much you've have to expand to do that and manage that within the budget, you could at least then identify those critical suppliers and look for certainty to make sure that they can continue providing those specialty parts and if you can at least pair it down, again, at a critical mass where you can demonstrate economies scale saving that you get at least say, these are the areas we need to maintain this industrial base especially for small scale suppliers that rely on certainty to continue that effort.

So have you all given any thoughts to be able to scale at least within that area maybe not to get 15 percent savings but still create certainty, make sure the suppliers are there but also gain saving.

STACKLEY:

Yes, sir. We have a very conservative effort going on for the Navy and Newport News [Shipbuilding] on all things cost related to the CVN 78 class for all the right reasons. We are looking ahead at [CVN] 80 which is a 2016— the advance procurement starts in 2016 for the [CVN] 80, most of that could be nuclear material.

But Newport News [Shipbuilding] has bought the initiative to the table in terms of combined buys from material and now we have to sort out can we in fact come up with the right list of material that make sense to buy early, to buy combined, to get the savings and not just savings people promising savings in the (inaudible) but to actually to be able to book the savings so we can drive down the cost to those carriers.

So we are—I would say that we're working with industry on that. We've got a long way to go to be able to carry the day inside the budget process. First inside the building and then again, I will tell you, we're going to have some challenges convincing some folks on the Hill that this makes sense to invest this early in the future aircraft carrier.22

Cost Growth and Managing Costs within Program Cost Caps

Overview

For the past several years, cost growth in the CVN-78 program, Navy efforts to stem that growth, and Navy efforts to manage costs so as to stay within the program's cost caps have been continuing oversight issues for Congress on the CVN-78 program.23 As shown in Table 2, the estimated procurement costs of CVNs 78, 79, and 80 have grown 23.1%, 23.8%, and 21.3%, respectively, since the submission of the FY2008 budget. Cost growth on CVN-78 required the Navy to program $1,374.9 million in cost-to-complete procurement funding for the ship in FY2014-FY2016, and to request another $20 million in cost-to-complete for FY2018 (see Table 1). As also shown in Table 2, however,

- while the estimated cost of CVN-78 grew considerably between the FY2008 budget (the budget in which CVN-78 was procured) and the FY2014 budget, it has remained generally stable in the FY2015, FY2016, FY2017, and FY2018 budgets;

- while the estimated cost of CVN-79 grew considerably between the FY2008 budget and the FY2013 budget (in part because the procurement date for the ship was deferred by one year in the FY2010 budget),24 it has fluctuated a bit but remained more or less stable since the FY2013 budget; and

- while the estimated cost of CVN-79 grew considerably between the FY2008 budget and the FY2011 budget (in part because the procurement date for the ship was deferred by two years in the FY2010 budget),25 it has decreased a bit since the FY2011 budget.

Recent Related Legislative Provisions

Section 128 of the FY2016 National Defense Authorization Act (S. 1356/P.L. 114-92 of November 25, 2015 states:

SEC. 128. Limitation on availability of funds for U.S.S. John F. Kennedy (CVN–79).

(a) Limitation.—Of the funds authorized to be appropriated by this Act or otherwise made available for fiscal year 2016 for procurement for the U.S.S. John F. Kennedy (CVN–79), $100,000,000 may not be obligated or expended until the date on which the Secretary of the Navy submits to the congressional defense committees the certification under subsection (b)(1) or the notification under paragraph (2) of such subsection, as the case may be, and the reports under subsections (c) and (d)....

(c) Report on costs relating to CVN–79 and CVN–80.—

(1) IN GENERAL.—Not later than 90 days after the date of the enactment of this Act, the Secretary of the Navy shall submit to the congressional defense committees a report that evaluates cost issues related to the U.S.S. John F. Kennedy (CVN–79) and the U.S.S. Enterprise (CVN–80).

(2) ELEMENTS.—The report under paragraph (1) shall include the following:

(A) Options to achieve ship end cost of no more than $10,000,000,000.

(B) Options to freeze the design of CVN–79 for CVN–80, with exceptions only for changes due to full ship shock trials or other significant test and evaluation results.

(C) Options to reduce the plans cost for CVN–80 to less than 50 percent of the CVN–79 plans cost.

(D) Options to transition all non-nuclear Government-furnished equipment, including launch and arresting equipment, to contractor-furnished equipment.

(E) Options to build the ships at the most economic pace, such as four years between ships.

(F) A business case analysis for the Enterprise Air Search Radar modification to CVN–79 and CVN–80.

(G) A business case analysis for the two-phase CVN–79 delivery proposal and impact on fleet deployments.

Section 126 of the FY2017 National Defense Authorization Act (S. 2943/P.L. 114-328 of December 23, 2016) states:

SEC. 126. Limitation on availability of funds for procurement of U.S.S. Enterprise (CVN–80).

(a) Limitation.—Of the funds authorized to be appropriated by this Act or otherwise made available for fiscal year 2017 for advance procurement or procurement for the U.S.S. Enterprise (CVN–80), not more than 25 percent may be obligated or expended until the date on which the Secretary of the Navy and the Chief of Naval Operations jointly submit to the congressional defense committees the report under subsection (b).

(b) Initial report on CVN–79 and CVN–80.—Not later than December 1, 2016, the Secretary of the Navy and the Chief of Naval Operations shall jointly submit to the congressional defense committees a report that includes a description of actions that may be carried out (including de-scoping requirements, if necessary) to achieve a ship end cost of—

(1) not more than $12,000,000,000 for the CVN–80; and

(2) not more than $11,000,000,000 for the U.S.S. John F. Kennedy (CVN–79).

(c) Annual report on CVN–79 and CVN–80.—

(1) IN GENERAL.—Together with the budget of the President for each fiscal year through fiscal year 2021 (as submitted to Congress under section 1105(a) of title 31, United States Code) the Secretary of the Navy and the Chief of Naval Operations shall submit a report on the efforts of the Navy to achieve the ship end costs described in subsection (b) for the CVN–79 and CVN–80.

(2) ELEMENTS.—The report under paragraph (1) shall include, with respect to the procurement of the CVN–79 and the CVN–80, the following:

(A) A description of the progress made toward achieving the ship end costs described in subsection (b), including realized cost savings.

(B) A description of low value-added or unnecessary elements of program cost that have been reduced or eliminated.

(C) Cost savings estimates for current and planned initiatives.

(D) A schedule that includes—

(i) a plan for spending with phasing of key obligations and outlays;

(ii) decision points describing when savings may be realized; and

(iii) key events that must occur to execute initiatives and achieve savings.

(E) Instances of lower Government estimates used in contract negotiations.

(F) A description of risks that may result from achieving the procurement end costs specified in subsection (b).

(G) A description of incentives or rewards provided or planned to be provided to prime contractors for meeting the procurement end costs specified in subsection (b).

Sources of Risk of Cost Growth and Navy Actions to Control Cost

Sources of risk of cost growth on CVN-78 in the past have included, among other things, certain new systems to be installed on CVN-78 whose development, if delayed, could delay the completion of the ship. These systems include a new type of aircraft catapult called the Electromagnetic Launch System (EMALS), a new aircraft arresting system called the Advanced Arresting Gear (AAG), and the ship's primary radar, called the Dual Band Radar (DBR). Congress has followed these and other sources of risk of cost growth for years.

In July 2016, the DOD Inspector General issued a report critical of the Navy's management of the AAG development effort.26 In January 2017, it was reported that after conducting a review of potential alternative systems, the Navy had decided to continue stay with its plan to install EMALs and AAG on the first three Ford-class carriers.27 Section 125 of the FY2017 National Defense Authorization Act (S. 2943/P.L. 114-328 of December 23, 2016) limits the availability of funds for the AAG program until certain conditions are met.

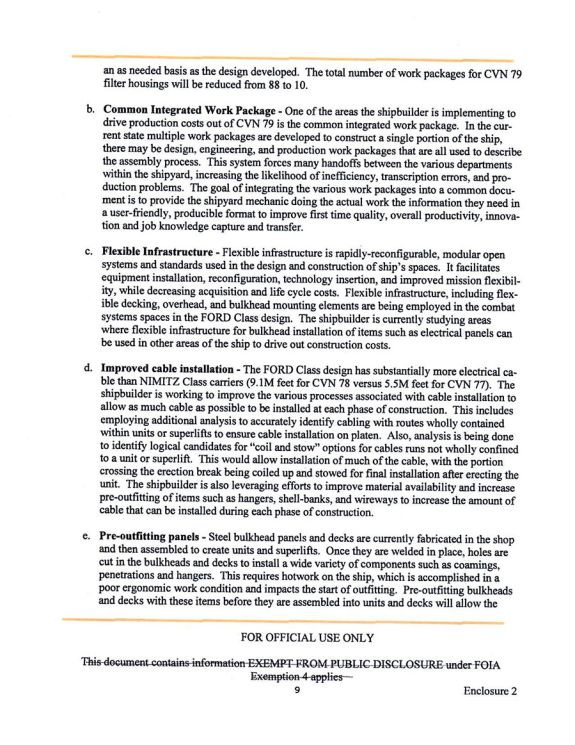

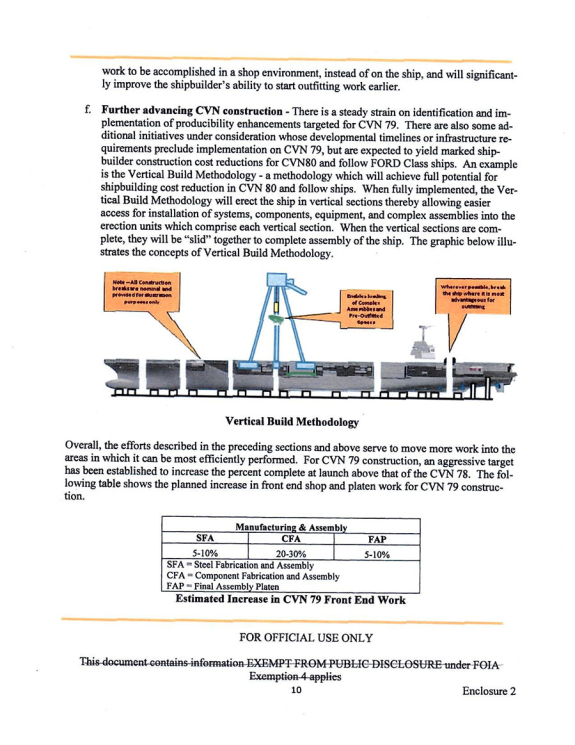

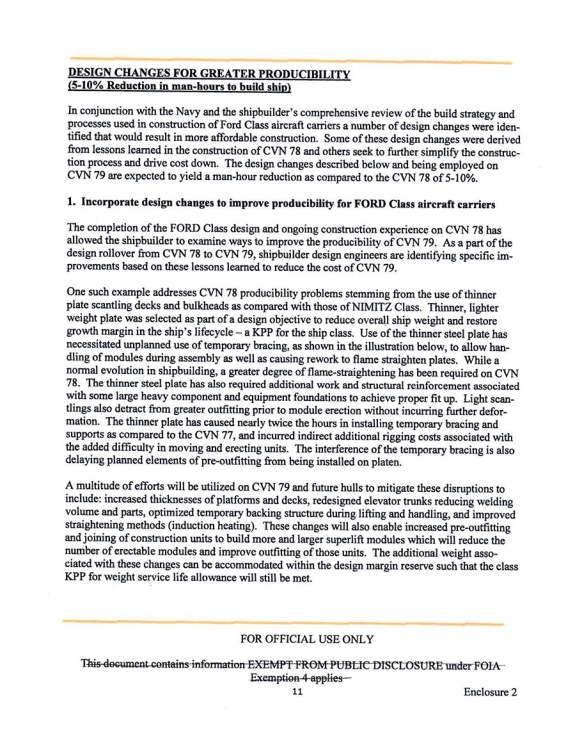

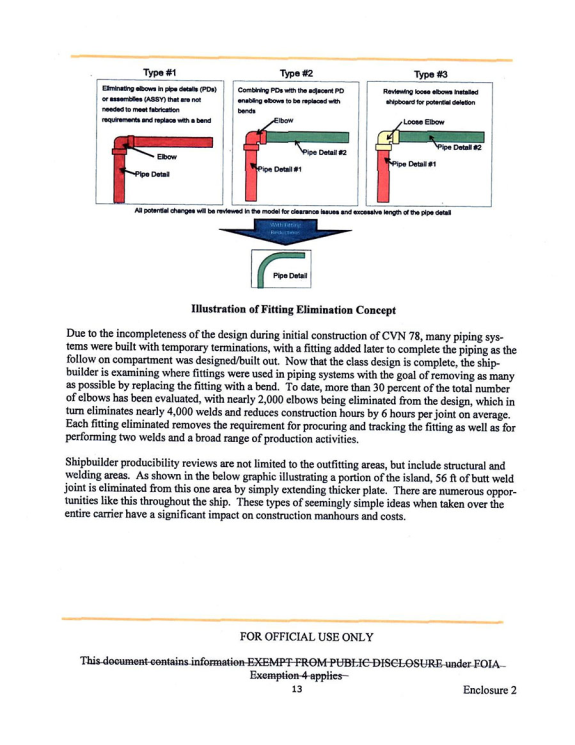

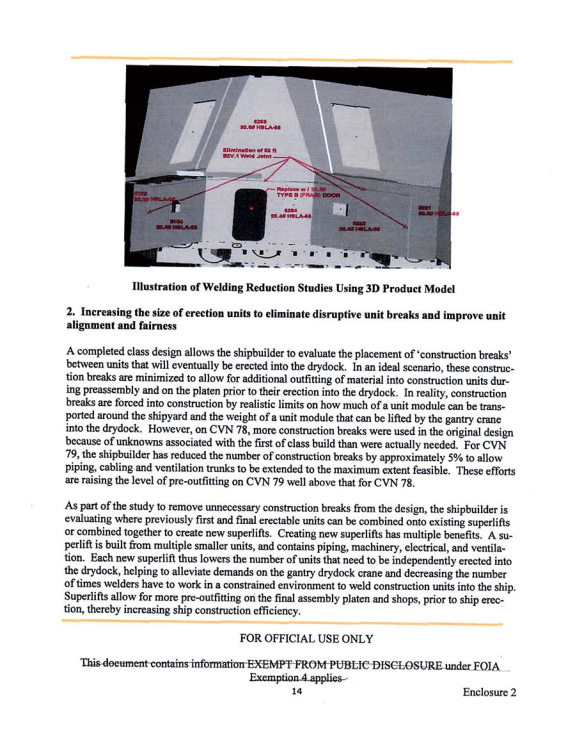

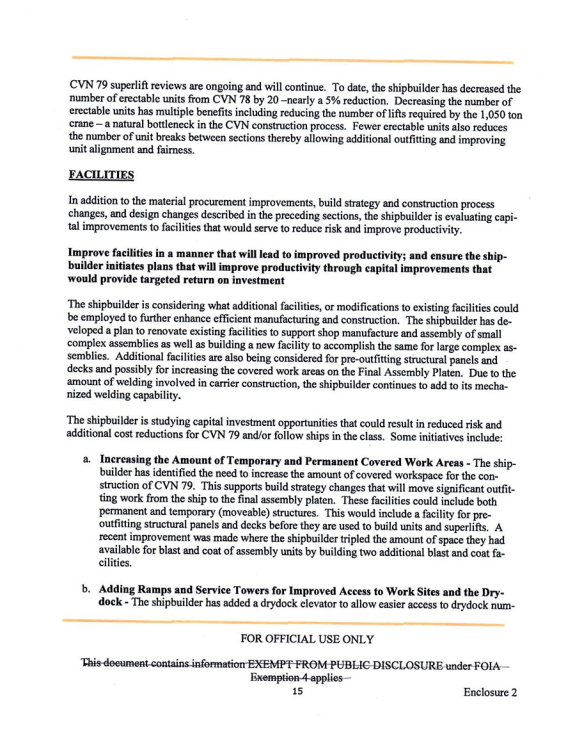

Navy officials have stated that they are working to control the cost of CVN-79 by equipping the ship with a less expensive primary radar,28 by turning down opportunities to add features to the ship that would have made the ship more capable than CVN-78 but would also have increased CVN-79's cost, and by using a build strategy for the ship that incorporates improvements over the build strategy that was used for CVN-78. These build-strategy improvements, Navy officials have said, include the following items, among others:

- achieving a higher percentage of outfitting of ship modules before modules are stacked together to form the ship;

- achieving "learning inside the ship," which means producing similar-looking ship modules in an assembly line-like series, so as to achieve improved production learning curve benefits in the production of these modules; and

- more economical ordering of parts and materials including greater use of batch ordering of parts and materials, as opposed to ordering parts and materials on an individual basis as each is needed.

Developments in 2016 and 2017

The Navy stated in 2016 that

The Navy is committed to delivering the lead ship of the class, Gerald R Ford (CVN 78) within the $12.887 billion congressional cost cap. Sustained efforts to identify cost reductions and drive improved cost and schedule performance on this first-of-class aircraft carrier have resulted in highly stable cost performance since 2011. Based on lessons learned on CVN 78, the approach to carrier construction has undergone an extensive affordability review and the Navy and the shipbuilder have made significant changes on CVN 79 to reduce the cost to build the ship. The benefits of these changes in build strategy and resolution of first-of-class impacts experienced on CVN 78 are evident in early production labor metrics on CVN 79. These efforts are ongoing and additional process improvements continue to be identified.

Alongside the Navy's efforts to reduce the cost to build CVN 79, the FY 2016 National Defense Authorization Act reduced the cost cap for follow ships in the CVN 78 class from $11,498 million to $11,398 million. To this end, the Navy has further emphasized stability in requirements, design, schedule, and budget, in order to drive further improvement to CVN 79 cost. The FY 2017 President's Budget requests funding for the most efficient build strategy for this ship and we look for Congress' full support of this request to enable CVN 79 procurement at the lowest possible cost....

... The Navy will deliver the CVN 79 within the cost cap using a two-phased strategy wherein select ship systems and compartments that are more efficiently completed at a later stage of construction - to avoid obsolescence or to leverage competition or the use of experienced installation teams - will be scheduled for completion in the ship's second phase of production and test. Enterprise (CVN 80) began construction planning and long lead time material procurement in January 2016 and construction is scheduled to begin in 2018. The FY 2017 President's Budget request re-phases CVN 80 funding to support a more efficient production profile, critical to performance, below the cost cap. CVN 80 planning and construction will continue to leverage class lessons learned to achieve cost and risk reduction, including efforts to accelerate production work to earlier phases of construction, where work is more cost efficient.29

A June 2017 Government Accountability Office (GAO) report states:

The cost estimate for the second Ford-Class aircraft carrier, CVN 79, is not reliable and does not address lessons learned from the performance of the lead ship, CVN 78. As a result, the estimate does not demonstrate that the program can meet its $11.4 billion cost cap. Cost growth for the lead ship was driven by challenges with technology development, design, and construction, compounded by an optimistic budget estimate. Instead of learning from the mistakes of CVN 78, the Navy developed an estimate for CVN 79 that assumes a reduction in labor hours needed to construct the ship that is unprecedented in the past 50 years of aircraft carrier construction....

After developing the program estimate, the Navy negotiated 18 percent fewer labor hours for CVN 79 than were required for CVN 78. CVN 79's estimate is optimistic compared to the labor hour reductions calculated in independent cost reviews conducted in 2015 by the Naval Center for Cost Analysis and the Office of Cost Assessment and Program Evaluation. Navy analysis shows that the CVN 79 cost estimate may not sufficiently account for program risks, with the current budget likely insufficient to complete ship construction.

The Navy's current reporting mechanisms, such as budget requests and annual acquisition reports to Congress, provide limited insight into the overall Ford Class program and individual ship costs. For example, the program requests funding for each ship before that ship obtains an independent cost estimate. During an 11-year period prior to 2015, no independent cost estimate was conducted for any of the Ford class ships; however, the program received over $15 billion in funding. In addition, the program's Selected Acquisition Reports (SAR)—annual cost, status, and performance reports to Congress—provide only aggregate program cost for all three ships currently in the class, a practice that limits transparency into individual ship costs. As a result, Congress has diminished ability to oversee one of the most expensive programs in the defense portfolio.30

At a June 15, 2017, hearing before the Senate Armed Services Committee on the Department of the Navy's proposed FY2018 budget, the following exchange occurred:

SENATOR JOHN MCCAIN (CHAIRMAN) (continuing):

Secretary Stackley, the Navy broached a cost cap for CVN-78. Do you believe that it has?

SEAN STACKLEY, ACTING SECRETARY OF THE NAVY:

Sir, right now our estimate for CVN-78, we're trying to hold it within the $12.887 billion number that was established several years ago. We have included a $20 million [procurement funding] request in this budget pending our determination regarding repairs that required for the...

MCCAIN:

Is that a breach of Nunn-McCurdy?31

STACKLEY:

Not at this point in time, sir, we're continuing to evaluate whether that additional funding will be required. We're doing everything we can to stay within the existing cap and we'll keep Congress informed as we complete our post-delivery assessment.

MCCAIN:

Problem is we haven't been informed. So either you bust the cap and breach Nunn-McCurdy—Nunn-McCurdy or you notify us. You haven't done either one.

STACKLEY:

Sir, we've been submitting monthly reports regarding the carrier, we've alerted the concern regarding the repairs that are being required for the motor turbine generator set and we've acknowledged the risk associated with those repairs. However, what we're trying to do is not incur those costs, avoid cost by other means, and as of right now we're not ready to trip that cost cap.

MCCAIN:

Well, it's either not allowable or it's allowable. It's not allowable, then you take a certain course of action. If it's allowable then you're required to notify Congress. You have done neither.

STACKLEY:

If we need to incur those costs, they will be allowable costs. We're trying to avoid that at this stage of time, sir.

MCCAIN:

I agree, but we were supposed to be notified—OK. I can tell you that you are either in violation of Nunn-McCurdy or you are in violation of the requirement that we be notified. You have done neither. There's two scenarios.

STACKLEY:

Sir, we have not broached the cost cap. If it becomes apparent that we'll need to go above the cost cap, we will notify Congress within—within the terms that you all have established.

MCCAIN:

OK. Well, I'll get it to you in writing but you still haven't answered the question because when there's a $20 million cost overrun, it's either allowable and then we have to be notified in one way. If it's not allowable, Nunn-McCurdy is—is reached. But anyway, maybe you can give us a more satisfactory explanation in writing, Mr. Secretary.32

A September 26, 2017, press report states:

Huntington Ingalls Industries Inc. is falling short of a U.S. Navy goal to reduce hours of labor on the second ship in the new Ford class of aircraft carriers in a drive to reduce costs, according to service documents.

With 34 percent of construction complete on the USS John F. Kennedy, Huntington Ingalls estimates it will be able to reduce labor hours by 16 percent from the hours needed to construct the first vessel, the Gerald R. Ford. That's less than the 17 percent reduction reported at the end of last year and the 18 percent goal the Navy negotiated in the primary construction contract for the carrier.

The "recent degradation in cost performance stems largely from the delayed availability of certain categories of material," such as pipe fittings, controllers, actuators and valves, according to the Navy's annual report on the program and updated figures obtained by Bloomberg News....

"We acknowledge that the cost reduction target for CVN-79," relative to the first carrier, "is challenging," Huntington Ingalls spokeswoman Beci Brenton said in an email, referring to the Kennedy by its Navy designation. "While it is still early in the ship's schedule, we are seeing positive results from" new initiatives to keep costs in check, she said....

Navy Secretary Richard Spencer told reporters last week that he will stay involved in monitoring the CVN-79's construction trends. "This is my personal approach—the CEO has to be involved."

A close watch is required "because there are so many moving parts and so many opportunities to do things in a more efficient manner," Spencer said.

The Navy has been working with the contractors "to mitigate technical risks and impacts of late material," Navy spokesman Victor Chen in an email. "The overall volume of late material items and associated impact to construction performance is declining. The Navy has hired third-party experts who are working collaboratively with the shipbuilder to identify manufacturing opportunities for efficiency gains" and to assist in implementing improvements....

The 18 percent reduction in labor hours was "quite optimistic" from the start, Michele Mackin, a Government Accountability Office director who oversees its shipbuilding assessments, said in an email. "Even based on that assumption, the $11.4 billion cost cap was unlikely to be met," she said. "If those labor-hour efficiencies are in fact not materializing, costs will go higher.

Also, "with the ship being over 30 percent complete, it's unlikely the shipbuilder can get back enough efficiencies to further reduce labor hours—the more complicated work is yet to come," she said.33

For additional background information on cost growth in the CVN-78 program, Navy efforts to stem that growth, and Navy efforts to manage costs so as to stay within the program's cost caps, see Appendix A and Appendix B.

Issues Raised in December 2016 DOT&E Report

Another oversight issue for Congress concerns CVN-78 program issues raised in a December 2016 report from DOD's Director, Operational Test and Evaluation (DOT&E)—DOT&E's annual report for FY2016. The report stated the following in its section on the CVN-78 program:

Assessment

Test Planning

• A TEMP [test and evaluation master plan] 1610 revision is under development to address problems with the currently-approved TEMP 1610, Revision B. The Program Office is in the process of refining the post-delivery schedule to further integrate testing and to include the FSST.

• The Navy has not finalized how it intends to extrapolate the live SGR [sortie generation rate] testing (six consecutive 12-hour fly days followed by two consecutive 24-hour fly days) to the 35-day design reference mission on which the SGR requirement is based. COTF [Commander, Operational Test and Evaluation Force] is working with the Program Office to identify required upgrades for the Seabasing/Seastrike Aviation Model to perform this analysis.

• The schedule to deliver the ship has slipped to December 2016 "under review," meaning the Navy is currently evaluating the power plant problems and repair timeline and is determining a new date for delivery. This new date is planned to be announced in mid‑December 2016. Further slips in the delivery are likely to affect schedules for the first at-sea OT&E of CVN 78. Currently, the Program Office is planning for two phases of initial operational testing. The first phase examines basic ship functionality as the ship prepares for flight operations; the second phase focuses on flight operations once the ship and crew are ready. The Navy plans to begin the first phase of testing in late FY18 or early FY19 before CVN 78's FSST. The FSST is followed by CVN 78's first Planned Incremental Availability (PIA), an extended maintenance period. The Navy then plans to complete the second phase of operational testing after the PIA in FY21, subsequent to when the ship would first deploy. To save resources and lower test costs, the test phases are aligned with standard carrier training periods as CVN 78 prepares for its first deployment. Further delays in the ship delivery are likely to push both phases of testing until after the PIA. As noted in previous annual reports, the CVN 78 test schedule has been aggressive, and the development and testing of EMALS, AAG, DBR, and the Integrated Warfare System are driving the ship's schedule independent of the requirement to conduct the FSST [full ship shock trial]. Continued delays in the ship's delivery will compress the ship's schedule and are likely to have ripple effects. Given all of the above, it is clear that the need to conduct the FSST is not a key factor driving the first deployment to occur in FY21.

Reliability

• CVN 78 includes several systems that are new to aircraft carriers; four of these systems stand out as being critical to flight operations: EMALS, AAG, DBR, and the Advanced Weapons Elevators (AWEs). Overall, the poor reliability demonstrated by AAG and EMALS and the uncertain reliability of DBR and AWEs pose the most significant risk to the CVN 78 IOT&E. All four of these systems are being tested for the first time in their shipboard configurations aboard CVN 78. The Program Office provided updates on the reliability of these systems in April 2016. Reliability estimates derived from test data for EMALS and AAG are discussed below. For DBR and AWE, only engineering reliability estimates have been provided to date.

EMALS

• EMALS testing to date has demonstrated that EMALS should be able to launch aircraft planned for CVN 78's air wing. However, present limitations on F/A-18E/F and EA‑tim18G configurations, as well as the system's demonstrated poor reliability during developmental testing, suggest operational difficulties lie ahead for meeting requirements and in achieving success in combat.

• With the current limitations on EMALS for launching the F/A 18E/F and EA-18G in operational configurations (e.g., wing-mounted 480-gallon EFTs [external fuel tanks] and heavy wing stores), CVN 78 will be able to fly F/A-18E/F and EA-18G, but not in configurations required for normal operations. Presently, these problems substantially reduce the operational effectiveness of F/A-18E/F and EA-18G flying combat missions from CVN 78. The Navy has developed fixes to correct these problems, but testing with manned aircraft to verify the fixes has been postponed to 2017.

• As of April 2016, the program estimates that EMALS has approximately 400 Mean Cycles Between Critical Failure (MCBCF) in the shipboard configuration, where a cycle represents the launch of one aircraft. While this estimate is above the rebaselined reliability growth curve, the rebaselined curve is well below the requirement of 4,166 MCBCF. At the current reliability, EMALS has a 7 percent chance of completing the 4-day surge and a 67 percent chance of completing a day of sustained operations as defined in the design reference mission. Absent a major redesign, EMALS is unlikely to support high-intensity operations expected in combat.

• The reliability concerns are exacerbated by the fact that the crew cannot readily electrically isolate EMALS components during flight operations due to the shared nature of the Energy Storage Groups and Power Conversion Subsystem inverters onboard CVN 78. The process for electrically isolating equipment is time-consuming; spinning down the EMALS motor/generators takes 1.5 hours by itself. The inability to readily electrically isolate equipment precludes EMALS maintenance during flight operations, reducing the system's operational availability.

AAG

• Testing to date has demonstrated that AAG should be able to recover aircraft planned for the CVN 78 air wing, but the poor reliability demonstrated to date suggests AAG will have trouble meeting operational requirements.

• The Program Office redesigned major components that did not meet system specifications during land-based testing. In April 2016, the Program Office estimated that the redesigned AAG had a reliability of approximately 25 Mean Cycles Between Operational Mission Failure (MCBOMF) in the shipboard configuration, where a cycle represents the recovery of one aircraft. This reliability estimate is well below the rebaselined reliability growth curve and well below the requirement of 16,500 MCBOMF specified in the requirements documents. At the current reliability, AAG has an infinitesimal chance of completing the 4-day surge and less than a 0.2 percent chance of completing a day of sustained operations as defined in the design reference mission. Without a major redesign, AAG is unlikely to support high intensity operations expected in combat.

• The reliability concerns are worsened by the current AAG design that does not allow Power Conditioning Subsystem equipment to be electrically isolated from high power buses, limiting corrective maintenance on below-deck equipment during flight operations. This reduces the operational availability of the system.

DBR

• Previous testing of Navy combat systems similar to CVN 78's revealed numerous integration problems that degrade the performance of the Integrated Warfare System. Many of these problems are expected to exist on CVN 78. The DBR testing at Wallops Island is typical of early developmental testing with the system still in the problem discovery phase. Current results reveal problems with tracking and supporting missiles in flight, excessive numbers of clutter/ false tracks, and track continuity concerns. The Navy recently extended DBR testing at Wallops Island until 4QFY17; however, more test‑analyze‑fix cycles are likely to be needed to develop and test DBR fixes so that the DBR can properly perform air traffic control and engagement support on CVN 78.

• Currently, the Navy has only engineering analysis of DBR reliability. The reliability of the production VSR equipment in the shipboard DBR system has not been assessed. While the Engineering Development Model (EDM) VSR being tested at Wallops Island has experienced failures, it is not certain whether these EDM VSR failure modes will persist during shipboard testing of the production VSR. Reliability data collection will continue at Wallops Island and during DBR operations onboard CVN 78. The Navy has identified funding shortfalls that are likely to delay important developmental testing of DBR and the Integrated Warfare System. Test delays are likely to affect CVN 78's readiness for IOT&E. Delays in the development and testing of these systems at Wallops Island have significantly compressed the schedule for self-defense testing of DDG 1000 and CVN 78 on the SDTS. This testing is essential for understanding these ships' capabilities to defend themselves and prevail in combat. The completion of self-defense testing for CVN 78, and the subsequent use of Probability of Raid Annihilation test bed for assessing CVN 78 self-defense performance, are dependent upon future Navy decisions that could include canceling MFR component-level shock qualification or deferring the availability of the SDTS MFR for installation on DDG 1002.

SGR

• CVN 78 is unlikely to achieve its SGR requirement. The target threshold is based on unrealistic assumptions including fair weather and unlimited visibility, and that aircraft emergencies, failures of shipboard equipment, ship maneuvers, and manning shortfalls will not affect flight operations. DOT&E plans to assess CVN 78 performance during IOT&E by comparing it to the SGR requirement as well as to the demonstrated performance of the Nimitz-class carriers.

• During the 2013 operational assessment, DOT&E conducted an analysis of past aircraft carrier operations in major conflicts. The analysis concludes that the CVN 78 SGR requirement is well above historical levels and that CVN 78 is unlikely to achieve that requirement.

• There are also concerns with the reliability of key systems that support sortie generation on CVN 78. Poor reliability of these critical systems could cause a cascading series of delays during flight operations that would affect CVN 78's ability to generate sorties, make the ship more vulnerable to attack, or create limitations during routine operations. DOT&E assesses the poor or unknown reliability of these critical subsystems will be the most significant risk to CVN 78's successful completion of IOT&E. The analysis also considered the operational implications of a shortfall and concluded that as long as CVN 78 is able to generate sorties comparable to Nimitz-class carriers, the operational capabilities of CVN 78 will be similar to that of a Nimitz‑class carrier.

Electric Plant

• A full-scale qualification unit of the shipboard component was manufactured and tested in a land-based facility in 2004. This test revealed no problems with the design of the original transformers or any other part of the main turbine generator. The design issues revealed during troubleshooting of the failed main turbine generator voltage regulating system transformer were introduced with the design changes incorporated following the transformer failure. Once alternate transformers were selected, the Navy did not perform sufficient land-based testing to validate that no system design flaws or vulnerabilities with the revised voltage regulating system design existed. The Navy considered the risk was low and did not want to further delay ship delivery for the testing. However, due to the failure, ship delivery continues to be delayed.

Manning

• Based on earlier Navy analysis of manning and the Navy's early experience with CVN 78, several areas of concern have been identified. The Navy is working with the ship's crew to resolve these problems.

• During some exercises, the berthing capacity for officers and enlisted will be exceeded, requiring the number of evaluators to be limited or the timeframe to conduct the training to be lengthened. This shortfall in berthing is further exacerbated by the 246 officer and enlisted billets (roughly 10 percent of the crew) identified in the Manning War Game III as requiring a face-to-face turnover. These turnovers will not all happen at one time, but will require heavy oversight and will limit the amount of turnover that can be accomplished at sea and especially during evaluation periods.

• Manning must be supported at the 100 percent level, although this is not the Navy's standard practice on other ships and the Navy's personnel and training systems may not be able to support 100 percent manning. The ship is extremely sensitive to manpower fluctuations. Workload estimates for the many new technologies such as catapults, arresting gear, radar, and weapons and aircraft elevators are not yet well-understood. Finally, the Navy is considering placing the ship's seven computer networks under a single department. Network management and the correct manning to facilitate continued operations is a concern for a network that is more complex than historically seen on Navy ships.

LFT&E [live fire test and evaluation]

• CVN 78 has many new critical systems, such as EMALS, AAG, AWE, and DBR that have not undergone shock trials on other platforms. Unlike past tests on other new classes of ships with legacy systems, the performance of CVN 78's new critical systems is unknown. Inclusion of data from shock trials early in a program has been an essential component of building survivable ships. The current state of modeling and component-level testing are not adequate to identify the myriad problems that have been revealed only through full ship shock testing. DOT&E has requested that the Navy provide the status of the programs component shock qualification at a minimum on a semi-annual basis to understand the vulnerability and recoverability of the ship.

Recommendations

• Status of Previous Recommendations. The Navy should continue to address the nine remaining FY10, FY11, FY13, FY14, and FY15 recommendations.

1. Finalize plans that address CVN 78 Integrated Warfare System engineering and ship's self-defense system discrepancies prior to the start of IOT&E.

2. Provide scheduling, funding, and execution plans to DOT&E for the live SGR test event during the IOT&E.

3. Continue to work with the Navy's Bureau of Personnel to achieve adequate depth and breadth of required personnel to sufficiently meet Navy Enlisted Classification fit/fill manning requirements of CVN 78.

4. Conduct system-of0systems developmental testing to preclude discovery of deficiencies during IOT&E.

5. Address the uncertain reliability of EMALS, AAG, DBR, and AWE. These systems are critical to CVN 78 flight operations, and are the largest risk to the program.

6. Aggressively fund and address a solution for the excessive EMALS holdback release dynamics during F/A-18E/F and EA-18G catapult launches with wing-mounted 480-gallon EFTs.

7. Begin tracking and reporting on a quarterly basis systems reliability for all new systems, but at a minimum for EMALS, AAG, DBR, and AWE.

8. The Navy should ensure the continued funding for component shock qualification of both government- and contractor-furnished equipment.

9. Submit a TEMP for review and approval by DOT&E incorporating the Deputy Secretary's direction to conduct the FSST before CVN 78's first deployment.

• FY16 Recommendations. The Navy should:

1. Ensure adequate funding of DBR and Integrated Warfare System developmental testing to minimize delays to the test schedule.

2. Provide DOT&E with component shock qualification program updates at a minimum of semi-annually, and maintain DOT&E's awareness of FY19 shock trial planning.34

Navy Study on Smaller Aircraft Carriers

Overview

Another oversight issue for Congress is whether the Navy should shift at some point from procuring large-deck, nuclear-powered carriers like the CVN-78 class to procuring smaller aircraft carriers. The issue has been studied periodically by the Navy and other observers over the years. To cite one example, the Navy studied the question in deciding on the aircraft carrier design that would follow the Nimitz (CVN-68) class.

Advocates of smaller carriers argue that they are individually less expensive to procure, that the Navy might be able to employ competition between shipyards in their procurement (something that the Navy cannot with large-deck, nuclear-powered carriers like the CVN-78 class, because only one U.S. shipyard, HII/NNS, can build aircraft carriers of that size), and that today's aircraft carriers concentrate much of the Navy's striking power into a relatively small number of expensive platforms that adversaries could focus on attacking in time of war.

Supporters of large-deck, nuclear-powered carriers argue that smaller carriers, though individually less expensive to procure, are less cost-effective in terms of dollars spent per aircraft embarked or aircraft sorties that can be generated, that it might be possible to use competition in procuring certain materials and components for large-deck, nuclear-powered aircraft carriers, and that smaller carriers, though perhaps affordable in larger numbers, would be individually less survivable in time of war than large-deck, nuclear-powered carriers.

Navy Study Initiated in 2015

At a March 18, 2015, hearing on Navy shipbuilding programs before the Seapower subcommittee of the Senate Armed Services Committee, the Navy testified that it had initiated a new study on the question. At the hearing, the following exchange occurred:

SENATOR JOHN MCCAIN, CHAIRMAN, SENATE ARMED SERVICES COMMITTEE, ATTENDING EX OFFICIO:

And you are looking at additional options to the large aircraft carrier as we know it.

SEAN STACKLEY, ASSISTANT SECRETARY OF THE NAVY FOR RESEARCH, DEVELOPMENT,AND ACQUISITION:

We've initiated a study and I think you've discussed this with the CNO [Chief of Naval Operations] and that's with the frontend of that study. Yes, sir.35

Later in the hearing, the following exchange occurred:

SENATOR ROGER WICKER, CHAIRMAN, SEAPOWER SUBCOMMITTEE:

Well, Senator McCain expressed concern about competition [in Navy shipbuilding programs]. And I think that was with, in regard to aircraft carriers.

SEAN J. STACKLEY, ASSISTANT SECRETARY OF THE NAVY FOR RESEARCH, DEVELOPMENT,AND ACQUISITION:

Yes, Sir.

WICKER:

Would you care to respond to that?

STACKLEY:

He made a generic comment that we need competition to help control cost in our programs and we are absolutely in agreement there. With specific regards to the aircraft carrier, we have been asked and we are following suit to conduct a study to look at alternatives to the Nimitz and Ford class size and type of aircraft carriers, to see if it make sense.

We've done this in the past. We're not going to simply break out prior studies, dust them off and resubmit it. We're taking a hard look to see is there—is there a sweet spot, something different other than today's 100,000 ton carrier that would make sense to provide the power projection that we need, that we get today from our aircraft carriers, but at the same time put us in a more affordable position for providing that capability.

WICKER:

OK. But right now, he's—he's made a correct factual statement with regard to the lack of competition.

STACKLEY:

Yes, Sir. There is—yes, there is no other shipyard in the world that has the ability to construct a Ford or a Nimitz nuclear aircraft carrier other than what we have in Newport News and the capital investment to do that is prohibitive to set up a second source, so obviously we are—we are content, not with the lack of competition, but we are content with knowing that we're only going to have one builder for our aircraft carriers.36

On March 20, 2015, the Navy provided the following additional statement to the press:

As indicated in testimony, the Navy has an ongoing study to explore the possible composition of our future large deck aviation ship force, including carriers. There is a historical precedent for these type[s] of exploratory studies as we look for efficiencies and ways to improve our war fighting capabilities. This study will reflect our continued commitment to reducing costs across all platforms by matching capabilities to projected threats and Also [sic] seeks to identify acquisition strategies that promote competition in naval ship construction. While I can't comment on an ongoing study, what I can tell you is that the results will be used to inform future shipbuilding budget submissions and efforts, beyond what is currently planned.37

Report Required by Section 128 of P.L. 114-92

Section 128 of the FY2016 National Defense Authorization Act (S. 1356/P.L. 114-92 of November 25, 2015) states:

SEC. 128. Limitation on availability of funds for U.S.S. John F. Kennedy (CVN–79).

(a) Limitation.—Of the funds authorized to be appropriated by this Act or otherwise made available for fiscal year 2016 for procurement for the U.S.S. John F. Kennedy (CVN–79), $100,000,000 may not be obligated or expended until the date on which the Secretary of the Navy submits to the congressional defense committees the certification under subsection (b)(1) or the notification under paragraph (2) of such subsection, as the case may be, and the reports under subsections (c) and (d)....

(d) Report on future development.—

(1) IN GENERAL.—Not later than April 1, 2016, the Secretary of the Navy shall submit to the congressional defense committees a report on potential requirements, capabilities, and alternatives for the future development of aircraft carriers that would replace or supplement the CVN–78 class aircraft carrier.

(2) ELEMENTS.—The report under paragraph (1) shall include the following:

(A) A description of fleet, sea-based tactical aviation capability requirements for a range of operational scenarios beginning in the 2025 timeframe.

(B) A description of alternative aircraft carrier designs that meet the requirements described under subparagraph (A).

(C) A description of nuclear and non-nuclear propulsion options.

(D) A description of tonnage options ranging from less than 20,000 tons to greater than 100,000 tons.

(E) Requirements for unmanned systems integration from inception.

(F) Developmental, procurement, and lifecycle cost assessment of alternatives.

(G) A notional acquisition strategy for the development and construction of alternatives.

(H) A description of shipbuilding industrial base considerations and a plan to ensure opportunity for competition among alternatives.

(I) A description of funding and timing considerations related to developing the Annual Long-Range Plan for Construction of Naval Vessels required under section 231 of title 10, United States Code.

The report required by Section 128(d) of P.L. 114-92, which was conducted for the Navy by the RAND Corporation, was delivered to the congressional defense committees in classified form in July 2016. An unclassified version of the report was then prepared and issued in 2017 as a publicly released RAND report. The executive summary of that report states (emphasis as in original):

We analyzed the feasibility of adopting four aircraft carrier concept variants as follow-ons to the Ford-class carrier following USS Enterprise (CVN 80) or the as-yet-unnamed CVN 81. Among these options are two large-deck carrier platforms that would retain the capability to launch and recover fixed-wing aircraft using an on-deck catapult and arresting gear system and two smaller carrier platforms capable of supporting only short takeoff and vertical landing (STVOL) aircraft. Specifically, the four concept variants are as follows:

• a follow-on variant continuing the current 100,000-ton Ford-class carrier but with two life-of-the-ship reactors and other equipment and system changes to reduce cost (we refer to this design concept as CVN 8X)

• a 70,000-ton USS Forrestal–size carrier with an updated flight deck and hybrid nuclear-powered integrated propulsion plant with capability to embark the current large integrated air wing but with reduced sortie generation capability, survivability, and endurance compared with the Ford class (we refer to this design concept as CVN LX)