Overview

Since assuming the throne from his late father on February 7, 1999, Jordan's 55-year-old monarch King Abdullah II bin Al Hussein (hereinafter King Abdullah II) has managed to maintain Jordan's stability and strong ties to the United States despite ongoing conflicts in two neighboring countries (Syria and Iraq) and recent tensions with its neighbor Israel, which Jordan has been at peace with since 1994. Although many commentators frequently caution that Jordan's stability is fragile, the monarchy has remained resilient owing to a number of factors. These include a relatively strong sense of social cohesion, strong support for the government from both Western powers and the Gulf Arab monarchies, and an internal security apparatus that is highly capable and, according to human rights groups, uses vague and broad criminal provisions in the legal system to dissuade dissent.1

In the last decade, the kingdom's stability has been repeatedly tested, as the economy faced the 2008 global financial crisis and the downturn following the regional unrest that began in 2011. Jordan's social cohesion has withstood the influx of hundreds of thousands of Iraqi and Syrian refugees who arrived between 2003 and 2016, despite widespread public perceptions that refugee communities have received disproportionate amounts of aid. The King himself has withstood domestic Islamist and pro-Palestinian opposition forces citing the lack of traction on the Israeli-Palestinian peace process. Finally, the kingdom's security services have withstood threats posed by the Islamic State organization (IS, also known as ISIL, ISIS, or the Arabic acronym Da'esh), despite both homegrown and external attacks.

As the kingdom endures these challenges, U.S. officials do not take Jordan's resilience for granted. President Trump has acknowledged Jordan's role as a key U.S. partner in countering IS, and the President and King Abdullah II have met at least four times in 2017. Jordanian officials have sought to stress the value of strong U.S.-Jordanian relations to U.S. policymakers and to advocate for continued robust U.S. assistance. U.S. foreign assistance to the kingdom has nearly quadrupled in overall value over the last 15 years due to Jordan's cooperation with U.S. counterterrorism forces and its hosting of Syrian refugees.2 Jordan also hosts thousands of U.S. troops. According to President Trump's June 2017 War Powers Resolution Report to Congress, "At the request of the Government of Jordan, approximately 2,850 United States military personnel are deployed to Jordan to support defeat-ISIS [sic] operations and the security of Jordan and to promote regional stability." In order to support U.S. assistance programs and a growing military presence, according to U.S. Institute for Peace, the number of personnel at the U.S. Embassy grew by nearly 75% between 2010 and 2016.3

|

|

Area: 89,213 sq. km. (34,445 sq. mi., slightly smaller than Indiana) Population: 8,185,384 (2016); Amman (capital): 1.155 million (2015) Ethnic Groups: Arabs 98%; Circassians 1%; Armenians 1% Religion: Sunni Muslim 97.2%; Christian 2% Percent of Population Under Age 25: 55% (2016) Literacy: 95.4% (2015) Youth Unemployment: 29.3% (2012) |

Source: Graphic created by CRS; facts from CIA World Factbook.

The Islamic State and Domestic Security

Jordan is a key contributor to the U.S.-led coalition to counter the Islamic State. Jordanian F-16s and other aircraft fly missions as part of Operation Inherent Resolve in Syria and Iraq. In limited instances, Jordanian ground forces and special operators have targeted IS fighters along the kingdom's border with Syria and Iraq.4 Jordanian and U.S. authorities5 are concerned not only with IS infiltration into the kingdom, but also IS radicalization of Jordanians who have fought in Syria. The kingdom is home to several areas where manifestations of antigovernment sentiment are high, economic prospects are poor, and sympathy for violent extremist groups appears to be prevalent.

In 2017, many observers remain concerned that even as the Islamic State loses territory in Iraq and Syria, the group will use its networks elsewhere, such as in Jordan, to continue attacking its adversaries. However, these small-scale attacks have not threatened the kingdom's overall stability to date. According to one analysis, "The stigma of terrorism and extremism repels [Jordanian] families and tribes across the country, who see it as a stain on their honor as a collective whole. This has led many [Jordanian] tribes and families to disown sons and daughters who have joined ISIL."6

The War in Southern Syria and Its Impact on Jordan

As Jordan confronts the complexity of the war in neighboring Syria, the kingdom finds itself dealing with a host of state and non-state actors, including the Syrian regime of President Bashar al Asad, Russia, the United States, Israel, Iran, Hezbollah, affiliates of Al Qaeda and the Islamic State, and various Syrian rebel groups. Overall, the kingdom supports a political solution to the conflict, though it reportedly has armed and supported various rebel factions near its borders. Support for these proxy forces may be Jordan's preferred means of containing the damage from the Syrian war without having it spill over into the kingdom any more than it already has, given the high number of Syrian refugees who have fled there.

Cease-Fire and De-escalation Zone in Southwestern Syria

In order to stem the flow of refugees, prevent terrorist infiltration, protect select U.S. and Jordanian-supported Syrian armed opposition groups and prevent non-state actors such as Hezbollah from gaining ground near Jordan's borders, Jordan (like Israel) had long sought U.S. and Russian cooperation in limiting conflict in southern Syria.7

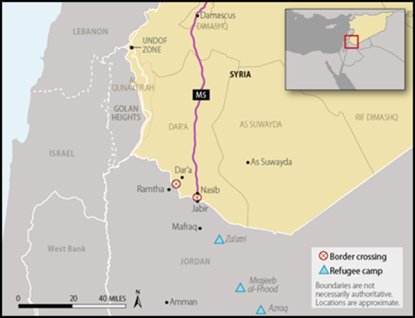

On July 9, 2017, the United States and Russia announced that both countries would cooperate in overseeing an open-ended cease-fire in parts of southwestern Syria and the creation of a de-escalation zone along the Jordanian-Syria border. Weeks earlier, military forces allied with the Asad regime had escalated air and artillery bombardments against various rebel-held positions in the city and province of Dara'a (where the 2011 uprising against Asad began) and other locations across southwestern Syria.8 When this offensive stalled, it created the impetus for combatants in southern Syria and their external backers to negotiate a localized cease-fire.9

The United States, Russia, and Jordan have delineated but not disclosed the precise borders of the de-escalation zone (parts of the southern provinces of Suwayda and Dara'a). Syrian opposition forces reportedly were not party to the discussions. The United States, Russia, and Jordan have established a monitoring and coordination center in Amman to monitor compliance in the de-escalation zone, and Russian military police have been deployed within Syrian government-controlled parts of the zone to monitor the cease-fire.10 To date, Jordanian officials approve the de-escalation zone arrangements and, according to one Jordanian government spokesperson, "Our relations with the Syrian state and regime are going in the right direction."11

The cease-fire/de-escalation zone deal also may have coincided with a reported shift in U.S. policy toward select Syrian opposition groups. According to one report, President Trump has ended covert U.S. arming and training of armed Syrian opposition groups.12 Some of these groups had been alleged to have received training and equipment in Jordan. In parallel, the Jordanian government may have instructed armed groups (such as Usoud al Sharqiya and Martyr Ahmad Abdo) it had been supporting to disband, relinquish their heavy weaponry, and leave southern Syria.13 CRS cannot independently confirm these media reports.

On November 8 in Amman, Jordan, the United States, Russia, and Jordan signed the Memorandum of Principles (or MOP), which, according to the State Department, "builds on and expands the July 7th ceasefire arrangement finalized during the last meeting between President Trump and President Putin in Hamburg, Germany, in July."14 The agreement reportedly "reflects the trilateral commitment that existing governance and administrative arrangements in opposition-held areas in the southwest [Syria] will be maintained during this transitional phase. In other words, the opposition is not surrendering territory to the regime, deferring those questions of longer-term political arrangements to the political process under UN Security Council Resolution 2254."15

The signing of the MOP has raised questions over the continued presence of Iranian-backed militias near the Israeli and Jordanian borders. According to the State Department, the MOP would enshrine "the commitment of the U.S., Russia, and Jordan to eliminate the presence of non-Syrian foreign forces. That includes Iranian forces and Iranian-backed militias like Lebanese Hezbollah as well as foreign jihadis working with Jabhat al Nusrah and other extremist groups from the southwest area."16 According to various news accounts, Russia has said that the MOP does not commit it to ensuring that all Iran-linked militias are removed from Syria, while unnamed Israeli sources claim that the MOP would permit militias associated with Iran to maintain positions as close as three to four miles from the Israeli border in some areas.17

|

|

Source: CRS Graphics. Note: M5 (purple line) is the main north-south highway in Syria. |

The Syrian Refugee Crisis in Jordan

Since 2011, the influx of Syrian refugees has placed tremendous strain on Jordan's government and local economies, especially in the northern governorates of Mafraq, Irbid, Ar Ramtha, and Zarqa. As of September 2017, there were 654,582 UNHCR-registered Syrian refugees in Jordan. Jordanian officials claim that there may be hundreds of thousands of unregistered refugees in the kingdom. Jordan has three official refugee camps, Zaatari, Azraq, and Mrajeed al Fhood, which have opened since 2012. While more than 100,000 refugees remain in the camp, the majority of Syrian refugees live amongst the wider population. Due to Jordan's small population size, it has one of the highest per capita refugee rates in the world.

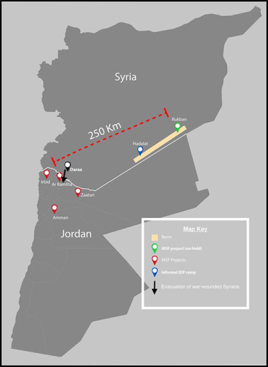

The government, which had already been limiting its intake of Syrian refugees, officially closed all entry points to the kingdom from Syria in June 2016 after a suicide bomb attack on the Jordanian-Syrian border killed seven people at the border crossing point near the remote camp at Al Rukban in eastern Syria (Figure 3). In order to improve the livelihoods of Syrian refugees already living in Jordan and to receive more external assistance from the international community, the Jordanian government has entered into an arrangement with foreign governments and international financial institutions known as the Jordan Compact. Reached in February 2016 at a donor conference in London, the Compact aims to provide work permits to 200,000 Syrian refugees, enabling them to be legally employed in the kingdom. Jordan also pledged to expand access to education for over 165,000 Syrian children. In return, the Jordanian government is to receive low-interest loans ($1.8 billion) from foreign creditors (such as the World Bank's Global Concessional Financing Facility) and preferential access to European markets for goods produced in special economic zones with a high degree of Syrian labor participation (15%). To date, the results of the Jordan Compact appear mixed, with some Syrians preferring informal work, while others are being issued legal work permits in the agricultural and construction sectors.18

|

|

Source: Notes: Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF). |

Syrian IDPs and "The Berm"

As of September 2017, approximately 50,000 Syrians remained stranded in remote areas of eastern Syria where earthen mounds (or berms) mark the approach to the border inside Syria.19 According to USAID, the population at the unofficial camp near the berm at Al Rukban includes large numbers of extremely vulnerable people—more than half are children. Periodically, the Jordanian government has used cranes to drop shipments of aid over the earthen wall demarcating the border. Living conditions at the makeshift camps at Rukban and Hadalat are poor, with no sanitation, running water, or electricity.

A June 2016 terrorist attack near the border led authorities to close the area, shutting down deliveries of humanitarian aid. Jordanian security services consider the zone a closed military area and continue to strictly regulate the operations of humanitarian organizations in the area. Jordanian authorities argue that allowing the populations at the berm camps to enter Jordan would pose an unacceptable security risk and could encourage other Syrian IDPs to travel to the border area in the hope of crossing. The Islamic State claims to have carried out two car bomb attacks against civilians and armed groups present near the Berm in 2017. In order to strengthen Jordan's military presence there, the United States has provided them mine-resistant ambush-protected vehicles (MRAPs) through the Excess Defense Articles (EDA) program. The Jordanian military also has remounted 20 mm rotary cannons on their MRAPs in order to destroy suicide vehicle-borne improvised explosive devices (SVBIEDs).20

Jordan and Israel

|

Holy Sites in Jerusalem21 Per arrangements with Israel dating back to 1967 and then subsequently confirmed in their 1994 bilateral peace treaty, Israel acknowledges a continuing role for Jordan vis-à-vis Jerusalem's historic Muslim shrines.22 A Jordanian waqf (or Islamic custodial trust) has long administered the Temple Mount (known by Muslims as the Haram al Sharif or Noble Sanctuary) and its holy sites, and this role is key to bolstering the religious legitimacy of the Jordanian royal family's rule. Successive Jordanian monarchs trace their lineage to the Prophet Muhammad. Disputes over Jerusalem that appear to circumscribe King Abdullah II's role as guardian of the Islamic holy sites create a domestic political problem for the King. Jewish worship on the Mount/Haram is prohibited under a long-standing "status quo" arrangement. |

The Jordanian government has long described efforts to secure a lasting end to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict as one of its highest priorities. In 1994, Jordan and Israel signed a peace treaty,23 and King Abdullah II has used his country's semi-cordial official relationship with Israel to improve Jordan's standing with Western governments and international financial institutions, on which it relies heavily for external support and aid. Nevertheless, the persistence of Israeli-Palestinian conflict continues to be a major challenge for Jordan. The issue of Palestinian rights resonates with much of the population; more than half of all Jordanian citizens originate from either the West Bank or the area now comprising the state of Israel.

Recent Jordanian-Israeli Tensions

Since the summer of 2017, diplomatic tensions between the governments of Jordan and Israel have been high owing to disputes over holy sites in Jerusalem and to an incident at the Israeli Embassy in Amman in which two Jordanian citizens were killed by an Israeli Embassy employee who claimed to be acting in self-defense. As in previous disputes between Israel and Jordan over Jerusalem (or other issues), bilateral tensions have domestic repercussions for both the Israeli and Jordanian governments.

In Jerusalem in July 2017, a succession of events at the Temple Mount/Haram al Sharif ("Mount/Haram") led to a diplomatic dispute involving Israel and Jordan. After three Arab Israelis shot and killed two Israeli police officers on the Mount/Haram on July 14, Israeli officials installed metal detectors for Muslim visitors, leading to calls of protest from the Jordanian government that Israel was altering the long-standing "status quo" arrangement for the Mount/Haram that it had agreed to uphold after taking control of East Jerusalem in 1967.

Shortly thereafter, at an Israeli Embassy residence in Amman, a dispute between a Jordanian furniture assembler and an Israeli Embassy security guard ended violently when the guard, who was reportedly attacked by the furniture contractor with a screwdriver, defended himself by shooting and killing the alleged attacker and, in the process, killed another Jordanian, possibly as an unintentional consequence of self-defense.

When the Israeli Embassy guard attempted to leave Jordan for Israel, claiming diplomatic immunity from prosecution, the Jordanian government prevented him and accompanying Israeli Embassy staff from departing. In order to facilitate their departure, Israel agreed to remove the metal detectors from the Mount/Haram access points, and Jordan then allowed the security guard and all other embassy staff (including Israel's Ambassador to Jordan) to return to Israel. Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu welcomed the guard warmly upon his arrival in Israel. King Abdullah II responded by calling this treatment of the guard "unacceptable and provocative behavior."24

As of October 2017, all Israeli Embassy staff in Amman remain in Israel. King Abdullah II has declared that no Israeli diplomat will be allowed to return until Israel has launched a full criminal police investigation into the Embassy shooting. Israel has launched a police probe of the shooting that is ongoing. A Jordanian government spokesperson responded to Israel's police probe, saying "We think this is a step in the right direction... We expect judicial action to follow in line with the international laws relevant to these cases. Justice must be served."25

Water Scarcity and Israeli-Jordanian-Palestinian Water Deal

Jordan is among the most water-poor nations in the world and ranks amongst the top ten countries with the lowest rate of renewable freshwater per capita.26 According to the Jordan Water Project at Stanford University, Jordan's increase in water scarcity over the last 60 years is attributable to an approximate 5.5-fold population increase since 1962, a decrease in the flow of the Yarmouk River due to the building of dams upstream in Syria, gradual declines in rainfall by an average of 0.4 mm/year since 1995, and depleting groundwater resources due to overuse.27

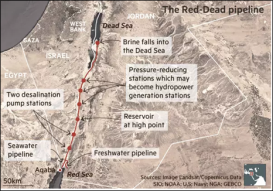

In order to secure new sources of freshwater, Jordan has pursued water cooperative projects with its neighbors. On December 9, 2013, Israel, Jordan, and the Palestinian Authority signed a regional water agreement (officially known as the Memorandum of Understanding on the Red-Dead Sea Conveyance Project, see Figure 4) to pave the way for the Red-Dead Canal, a multi-billion dollar project to address declining water levels in the Dead Sea. The agreement was essentially a commitment to a water swap, whereby half of the water pumped from the Red Sea is to be desalinated in a plant to be constructed in Aqaba, Jordan. Some of this water is to then be used in southern Jordan. The rest is to be sold to Israel for use in the Negev Desert. In return, Israel is to sell fresh water from the Sea of Galilee to northern Jordan and sell the Palestinian Authority discounted fresh water produced by existing Israeli desalination plants on the Mediterranean. The other half of the water pumped from the Red Sea (or possibly the leftover brine from desalination) is to be channeled to the Dead Sea. The exact allocations of swapped water were not part of the 2013 MOU and were left to future negotiations.

|

|

Source: Financial Times, March 22, 2017. |

In 2017, with Trump Administration officials seemingly committed to reviving the moribund Israeli-Palestinian peace process, U.S. officials focused on finalizing the terms of the 2013 MOU. In July 2017, the White House announced that U.S. Special Representative for International Negotiations Jason Greenblatt had "successfully supported the Israeli and Palestinian efforts to bridge the gaps and reach an agreement," with the Israeli government agreeing to sell the Palestinian Authority (PA) 32 million cubic meters (MCM) of fresh water.28

Congress has supported the Red-Dead Sea Conveyance Project. P.L. 114-113, the FY2016 Omnibus Appropriations Act, specifies that $100 million in Economic Support Funds be set aside for water sector support for Jordan, to support the Red Sea-Dead Sea water project. In September 2016, USAID notified Congress that it intended to spend the $100 million in FY2016 ESF-OCO on Phase One of the project.29

Country Background

Although the United States and Jordan have never been linked by a formal treaty, they have cooperated on a number of regional and international issues for decades. Jordan's small size and lack of major economic resources have made it dependent on aid from Western and various Arab sources. U.S. support, in particular, has helped Jordan deal with serious vulnerabilities, both internal and external. Jordan's geographic position, wedged between Israel, Syria, Iraq, and Saudi Arabia, has made it vulnerable to the strategic designs of its powerful neighbors, but has also given Jordan an important role as a buffer between these countries in their largely adversarial relations with one another.

Jordan, created by colonial powers after World War I, initially consisted of desert or semi-desert territory east of the Jordan River, inhabited largely by people of Bedouin tribal background. The establishment of the state of Israel in 1948 brought large numbers of Palestinian refugees to Jordan, which subsequently unilaterally annexed a Palestinian enclave west of the Jordan River known as the West Bank.30 The original "East Bank" Jordanians, though probably no longer a majority in Jordan, remain predominant in the country's political and military establishments and form the bedrock of support for the Jordanian monarchy. Jordanians of Palestinian origin comprise an estimated 55% to 70% of the population and generally tend to gravitate toward the private sector due to their general exclusion from certain public-sector and military positions.31

The Hashemite Royal Family

Jordan is a hereditary constitutional monarchy under the prestigious Hashemite family, which claims descent from the Prophet Muhammad. King Abdullah II (age 55) has ruled the country since 1999, when he succeeded to the throne upon the death of his father, the late King Hussein, after a 47-year reign. Educated largely in Britain and the United States, King Abdullah II had earlier pursued a military career, ultimately serving as commander of Jordan's Special Operations Forces with the rank of major general. The king's son, Prince Hussein bin Abdullah (born in 1994), is the designated crown prince.32

The king appoints a prime minister to head the government and the Council of Ministers (cabinet). On average, Jordanian governments last no more than 15 months before they are dissolved by royal decree. This seems to be done in order to bolster the king's reform credentials and to distribute patronage among a wide range of elites. The king also appoints all judges and is commander of the armed forces.

Political System and Key Institutions

The Jordanian constitution, most recently amended in 2016, empowers the king with broad executive powers. The king appoints the prime minister and may dismiss him or accept his resignation. He also has the sole power to appoint the crown prince, senior military leaders, justices of the constitutional court, and all 75 members of the senate. The king appoints cabinet ministers. The constitution enables the king to dissolve both houses of parliament and postpone lower house elections for two years.33 The king can circumvent parliament through a constitutional mechanism that allows provisional legislation to be issued by the cabinet when parliament is not sitting or has been dissolved.34 The king also must approve laws before they can take effect, although a two-thirds majority of both houses of parliament can modify legislation. The king also can issue royal decrees, which are not subject to parliamentary scrutiny. The king commands the armed forces, declares war, and ratifies treaties. Finally, Article 195 of the Jordanian Penal Code prohibits insulting the dignity of the king (lèse-majesté), with criminal penalties of one to three years in prison.

Jordan's constitution provides for an independent judiciary. According to Article 97, "Judges are independent, and in the exercise of their judicial functions they are subject to no authority other than that of the law." Jordan has three main types of courts: civil courts, special courts (some of which are military/state security courts), and religious courts. In Jordan, state security courts administered by military (and civilian) judges handle criminal cases involving espionage, bribery of public officials, trafficking in narcotics or weapons, black marketeering, and "security offenses." Overall, the king may appoint and dismiss judges by decree, though in practice a palace-appointed Higher Judicial Council manages court appointments, promotions, transfers, and retirements.

Although King Abdullah II has envisioned Jordan's gradual transition from a constitutional monarchy into a full-fledged parliamentary democracy,35 in reality, successive Jordanian parliaments have mostly complied with the policies laid out by the Royal Court. The legislative branch's independence has been curtailed not only by a legal system that rests authority largely in the hands of the monarch, but also by carefully crafted electoral laws designed to produce pro-palace majorities with each new election.36 Due to frequent gerrymandering in which electoral districts are drawn to favor more rural pro-government constituencies over densely populated urban areas, parliamentary elections have produced large pro-government majorities dominated by representatives of prominent tribal families. In addition, voter turnout tends to be much higher in pro-government areas since many East Bank Jordanians depend on family/tribal connections as a means to access patronage jobs.

The Economy

There is widespread dissatisfaction in Jordan with the state of the economy. With few natural resources and a small industrial base, Jordan's economy is heavily dependent on aid from abroad, tourism, expatriate worker remittances, and the service sector.37 Like many other countries, economic growth in Jordan is uneven, with higher growth in the urban core of the capital Amman and stagnation in the poorer and more rural areas of southern Jordan.

Jordan's economy continues to slowly grow at 2% annually, a rate insufficient for lowering unemployment and the national debt. According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), "Despite considerable progress and recent improvements, the outlook remains challenging."38 In 2016, the IMF and Jordan reached a new, three-year $723 million extended fund facility (EFF) agreement that commits Jordan to improving the business environment for the private sector, reducing budget expenditures, and reforming the tax code. As a result, Jordan has enacted a new Value Added Tax (VAT) to raise revenue. However, according to the Economist Intelligence Unit, the government also has raised the minimum wage, slowed its cutback of the state payroll, and expanded welfare payments—all of which add to its fiscal burden.39 The government has taken steps to alleviate its dependence on external sources of hydrocarbons by expanding its domestic renewable energy capacity. Several solar plants are already under construction and, when completed, will comprise up to 10% of the country's total energy mix.

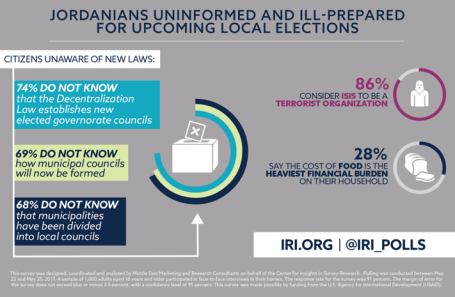

|

Figure 5. Public Opinion Polling in Jordan IRI Data on Elections and the Economy (July 12, 2017) |

|

|

Source: The International Republican Institute. |

In order to comply with IMF-mandated macroeconomic reforms, the Jordanian government has indicated that it may increase personal income taxes in order to raise government revenue and ease the public debt burden. Some analysts are concerned that if such changes are insufficiently explained to the public, there could be a backlash against tax increases, especially amongst lower income groups who are dependent on the public services and subsidies that have been reduced to comply with IMF lending.40 According to recent polling by the International Republican Institute (IRI), "the under-performing economy is starting to have a greater impact on Jordanian citizens. Just 22 percent of Jordanians describe the economic situation as 'good' (20 percent) or 'very good' (2 percent), continuing a downward trend from a high of 49 percent (46 percent 'good,' 3 percent 'very good') in 2015."41

U.S. Foreign Assistance to Jordan

The United States has provided economic and military aid to Jordan since 1951 and 1957, respectively. Total bilateral U.S. aid (overseen by State and the Department of Defense) to Jordan through FY2016 amounted to approximately $19.2 billion. Jordan has received $909 million in additional military aid since FY2014, with more being channeled through the Defense Department's security assistance accounts.

FY2017 Omnibus

P.L. 115-31, the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2017, provides the following for Jordan:

- "Not less than" $1.279 billion in bilateral aid to Jordan from State and Foreign Operations accounts.

- "Up to" $500 million in funds from the Defense Department's Operation and Maintenance, Defense-Wide account to support the armed forces of Jordan and to enhance security along its borders.

- $180 million for the governments of Jordan and Lebanon from the Defense Department's "Counter-Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant Train and Equip Fund" to enhance the border security of nations adjacent to conflict areas, including Jordan and Lebanon, resulting from actions of the Islamic State.

- An unspecified amount of ESF is authorized to meet the costs of Loan Guarantees for Jordan.

FY2018 Budget Request

For FY2018, the President is requesting $1 billion in U.S. foreign assistance to Jordan, most of which is comprised of two accounts: $635.8 million in Economic Support and Development Funds (ESDF) and $350 million in Foreign Military Financing Overseas Contingency Operations (FMF-OCO). The FY2018 ESDF request for Jordan makes up approximately 40% of all requested bilateral economic aid to the Middle East. The FY2018 budget request also would continue FMF grant funding for Jordan, rather than converting FMF grants to loans.

Three-Year MOU on U.S. Foreign Aid to Jordan

On February 3, 2015, the Obama Administration and the Jordanian government signed a nonbinding, three-year memorandum of understanding (MOU), in which the United States pledges to provide the kingdom with $1 billion annually in total U.S. foreign assistance, subject to the approval of Congress, from FY2015 through FY2017. This MOU followed a previous five-year agreement in which the United States had pledged to provide a total of $660 million annually from FY2009 through FY2014. During those five years, Congress actually provided Jordan with $4.753 billion in total aid, or $1.453 billion ($290.6 million annually) above what was agreed to in the five-year MOU, including more than $1 billion in FY2014.

In the months ahead, Jordanian officials may seek Congress' support in engaging the Trump Administration in negotiations for a new Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) on U.S. aid to Jordan, which could commit the United States to even higher amounts of aid. According to President Trump's FY2018 budget request to Congress, the Administration is seeking $1 billion in total U.S. aid to Jordan, which is "consistent with the previous FY2015-FY2017 Memorandum of Understanding level of $1.0 billion per year."

Economic Assistance

The United States provides economic aid to Jordan both as a cash transfer and for USAID programs in Jordan. The Jordanian government uses cash transfers to service its foreign debt. Approximately 40% to 60% of Jordan's ESF allotment may go toward the cash transfer.42 USAID programs in Jordan focus on a variety of sectors including democracy assistance, water preservation, and education (particularly building and renovating public schools). In the democracy sector, U.S. assistance has supported capacity-building programs for the parliament's support offices, the Jordanian Judicial Council, the Judicial Institute, and the Ministry of Justice.

The International Republican Institute and the National Democratic Institute also have received U.S. grants to train, among other groups, some Jordanian political parties and members of parliament. In the water sector, the bulk of U.S. economic assistance is devoted to optimizing the management of scarce water resources, as Jordan is one of the most water-deprived countries in the world. USAID is currently subsidizing several waste treatment and water distribution projects in the Jordanian cities of Amman, Mafraq, Aqaba, and Irbid.

Humanitarian Assistance for Syrian Refugees in Jordan

The U.S. State Department estimates that, since large-scale U.S. aid to Syrian refugees began in FY2012, it has allocated more than $1 billion in humanitarian assistance from global accounts for programs in Jordan to meet the needs of Syrian refugees and, indirectly, to ease the burden on Jordan.43 U.S. aid supports refugees living in camps (~141,000) and those living in towns and cities (~500,000). According to the State Department, U.S. humanitarian assistance is provided both as cash assistance and through programs to meet basic needs, such as child health care, water, and sanitation.

The U.S. government provides cross-border humanitarian and stabilization assistance to Syrians via programs monitored and implemented through the Embassy Amman-based Southern Syria Assistance Platform. This includes humanitarian assistance to areas of southern and eastern Syria that are otherwise inaccessible, as well as congressionally-authorized stabilization and non-lethal assistance to opposition-held areas in southern Syria. According to USAID, U.S. humanitarian assistance funds are enabling UNICEF to provide health assistance for Syrian populations sheltering at the informal Rukban and Hadalat settlements along the Syria-Jordan border berm, including daily water trucking, the rehabilitation of a water borehole, and installation of a water treatment unit in Hadalat.44

Loan Guarantees

The Obama Administration provided three loan guarantees to Jordan, totaling $3.75 billion.45 These include the following:

- In September 2013, the United States announced that it was providing its first-ever loan guarantee to the Kingdom of Jordan. USAID notified Congress of its intent to obligate up to $120 million in FY2013 ESF-OCO to support a $1.25 billion, seven-year sovereign loan guarantee for Jordan.

- In February 2014, during a visit to the United States by King Abdullah II, the Obama Administration announced that it would offer Jordan an additional five-year, $1 billion loan guarantee. USAID notified Congress of its intent to obligate $72 million out of the $340 million of FY2014 ESF-OCO for Jordan to support the subsidy costs for the second loan guarantee.

- In June 2015, the Obama Administration provided its third loan guarantee to Jordan of $1.5 billion. USAID notified Congress of its intent to obligate $221 million in FY2015 ESF to support the subsidy costs of the third loan guarantee to Jordan.46

Military Assistance

Foreign Military Financing

U.S.-Jordanian military cooperation is a key component in bilateral relations. U.S. military assistance is primarily directed toward enabling the Jordanian military to procure and maintain conventional weapons systems.47 The United States and Jordan have jointly developed a five-year procurement plan for the Jordanian Armed Forces in order to prioritize Jordan's needs and procurement budget using congressionally-appropriated Foreign Military Financing (FMF). Proposed arms sales notified to Congress include 35 Meter Coastal Patrol Boats; M31 Unitary Guided Multiple Launch Rocket Systems (GMLRS) Rocket Pods; UH-60M VIP Blackhawk helicopter; and repair and return of F-16 engines.48 On February 18, 2016, President Obama signed the United States-Jordan Defense Cooperation Act of 2015 (P.L. 114-123), which authorizes expedited review and an increased value threshold for proposed arms sales to Jordan for a period of three years. In July 2017, the United States delivered two S-70 Blackhawk helicopters to Jordan, bringing their total Blackhawk fleet up to 26 aircraft.

Excess Defense Articles

In 1996, the United States granted Jordan Major Non-NATO Ally (MNNA) status, a designation that, among other things, makes Jordan eligible to receive excess U.S. defense articles, training, and loans of equipment for cooperative research and development.49 In the last five years, Jordan has received excess U.S. defense articles, including two C-130 aircraft, HAWK MEI-23E missiles, and cargo trucks.

Defense Department Assistance

As a result of the Syrian civil war and Operation Inherent Resolve against IS, the United States has increased military aid to Jordan and channeled these increases through Defense Department-managed accounts. Although Jordan still receives the bulk of U.S. military aid from the FMF account, Congress has authorized defense appropriations to strengthen Jordan's border security. Congress has authorized Jordan to receive funding from various accounts such as: (1) Section 1206/10 U.S.C. 2282 Authority to Build Partner Capacity,50 (2) the Counterterrorism Partnerships Fund (CTPF),51 and (3) Department of Defense Operations & Maintenance Funds (O&M).52 Activities permitted under 10 U.S.C. 2282 have been incorporated into a new, broader global train and equip authority established by Section 1241(c) of the FY2017 NDAA: 10 U.S.C. 333.53 Military aid provided by these accounts is generally coordinated through a joint Defense Department (DOD)-State Department (DOS) review and approved by the Secretary of Defense, with the concurrence of the Secretary of State.

|

Account |

FY2014 |

FY2015 |

FY2016 est. |

FY2017 est. |

FY2018 est. |

|

State Dept.—ESF (+OCO) |

700.000 |

615.000 |

812.350 |

812.350 |

TBD |

|

State Dept.—FMF (+OCO) |

300.000 |

385.000 |

450.000 |

450.000 |

TBD |

|

State Dept.—NADR |

6.700 |

7.200 |

8.850 |

13.600 |

TBD |

|

IMET |

3.500 |

3.800 |

3.733 |

4.000 |

TBD |

|

DOD O&M (Coalition Support Funds) |

— |

147.0 (allocated over 2014-2015) |

154.700 |

TBD |

TBD |

|

DOD—1206/2282 (CTPF) |

— |

276.930 |

162.930 |

84.700 |

— |

|

DOD—2282 |

— |

27.762 |

55.000 |

TBD |

TBD |

|

DOD-10 U.S.C. 333 |

— |

— |

— |

— |

19.43 |

|

Total |

1,010.200 |

1,462.692 |

1,647.563 |

1,364.650 |

TBD |

Source: U.S. State and Defense Departments.

Recent Legislation

H.R. 3354, "House Omnibus." Would provide not less than $1.280 billion for assistance for Jordan, "of which not less than $475 million shall be for budget support (cash transfer) for the Government of Jordan." The bill also would authorize ESF funds from the act and prior acts to support the costs of loan guarantees for Jordan. The bill also would provide for defense appropriations (Operation and Maintenance, Defense-Wide) to support the Government of Jordan "in such amounts as the Secretary of Defense may determine." The bill also directs that funds for the "Counter-Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant Train and Equip Fund" be used to enhance the border security of Jordan. Finally, the bill also would allow "up to $500 million of funds appropriated by this Act for the Defense Security Cooperation Agency in Operation and Maintenance, Defense-Wide" to provide assistance to the Government of Jordan to support the armed forces of Jordan and to enhance security along its borders.

S. 1780, Department of State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs Appropriations Act, 2018. Would provide $1.5 billion in total aid to Jordan, of which not less than $1.082 billion shall be in ESF, $400 million in FMF. The bill also directs that $745.1 million in ESF be set aside for cash transfer to the government of Jordan. The bill also would authorize ESF funds from the act and prior acts to support the costs of loan guarantees for Jordan. In report language accompanying the bill, appropriators direct the Secretary of State to "negotiate an MOU with Jordan in a timely manner, particularly as the current MOU expired in fiscal year 2017."

House (H.R. 2810) and Senate National Defense Authorization Acts (S. 1519). Both the House and Senate versions of the FY2018 NDAA would authorize $143 million in Air Force construction funds to expand the ramp space at Muwaffaq Salti Air Base in Azraq, Jordan.

H.R. 2646, United States-Jordan Defense Cooperation Extension Act. Would amend the United States-Jordan Defense Cooperation Act of 2015 to extend Jordan's inclusion among the countries eligible for certain streamlined defense sales until December 31, 2022. The bill also would authorize an enterprise fund to provide assistance to Jordan.

|

Account |

1946-2011 |

FY2012 |

FY2013 |

FY2014 |

FY2015 |

FY2016 |

1946-2016 |

|

FMF |

3,380.800 |

300.000 |

284.800 |

300.000 |

385.000 |

450.000 |

5,100.600 |

|

ESF |

6,043.800 |

485.500 |

542.900 |

329.600 |

594.700 |

812.350 |

8,808.850 |

|

INCLE |

3.800 |

1.200 |

— |

0.800 |

0.200 |

— |

6.000 |

|

NADR |

110.600 |

18.400 |

12.200 |

6.100 |

5.400 |

8.850 |

166.300 |

|

IMET |

70.700 |

3.700 |

3.600 |

3.600 |

3.800 |

3.733 |

89.400 |

|

MRA |

82.100 |

35.200 |

167.100 |

157.600 |

162.500 |

tbd |

604.500 |

|

Other |

2,963.500 |

330.100 |

199.400 |

345.700 |

365.400 |

322.930 |

4,527.030 |

|

Total |

12,655.300 |

1,174.100 |

1,210.000 |

1,143.400 |

1,517.000 |

1,597.863 |

19,297.663 |

Source: USAID Overseas Loans and Grants, July 1, 1945-September 30, 2015.

Notes: "Other" accounts include economic and military assistance programs administered by USAID, State, and other federal agencies which are funded at less than $2 million annually. It also includes larger, more recent funding through the International Disaster Assistance account (IDA), Millennium Challenge Account, and several defense department funding accounts. It also encapsulates much larger legacy programs (food aid), some of which have been phased out over time.