Introduction

There are two tax provisions that subsidize the child and dependent care expenses of working parents: the child and dependent care tax credit (CDCTC) and the exclusion for employer-sponsored child and dependent care. This report provides a general overview of these two tax benefits, focusing on eligibility requirements and benefit calculation. The report also includes some summary data on these benefits which highlight some of the characteristics of claimants.

Child and Dependent Care Tax Credit

The child and dependent care tax credit is a nonrefundable tax credit that reduces a taxpayer's federal income tax liability based on child and dependent care expenses incurred so the taxpayer can work or look for work.1 Since the credit (sometimes referred to as the child care credit or the CDCTC) is nonrefundable, the amount of the credit cannot exceed a taxpayer's federal income tax liability. Taxpayers with little or no federal income tax liability—including many low-income taxpayers—generally receive little if any benefit from nonrefundable credits like the CDCTC.

Eligibility for the Credit

To claim the child and dependent care credit, a taxpayer must meet a variety of eligibility criteria. The taxpayer must have qualifying expenses for a qualifying individual, have earned income, and file taxes with an allowable filing status. These are defined briefly below.

- Qualifying expenses: Qualifying expenses are generally defined as expenses incurred for the care of a qualifying individual so that a taxpayer (and their spouse, if filing jointly) can work or look for work. Payments made to a relative for child and dependent care may be eligible for the credit, unless the relative is the taxpayer's dependent, child under 19 years old, spouse, or the parent of a qualifying child. Taxpayers claiming the CDCTC generally must provide the name, address, and taxpayer identification number of any person or organization that provides care for a qualifying individual.

- Qualifying individual: A qualifying individual for the CDCTC is either (1) the taxpayer's dependent child under 13 years of age, or (2) the taxpayer's spouse or dependent who is incapable of caring for himself or herself.

- Earned income: A taxpayer must have earned income to claim the credit. The amount of qualifying expenses claimed for the credit cannot be greater than the taxpayer's earned income for the year (or the earned income of the lower-earning spouse in the case of married taxpayers). For married couples filing jointly, both spouses must have earnings unless one is either a student or incapable of self-care.

- Taxes filed with an allowable filing status: Taxpayers are generally ineligible for the CDCTC if they file their taxes as "married filing separately."

Qualifying Expenses

Qualifying expenses for the credit are generally defined as expenses for the care of a qualifying individual so that a taxpayer (and their spouse, if filing jointly) can work or look for work.2 An expense is not considered work-related merely because a taxpayer paid or incurred the expense while working or looking for work. The purpose of the expense must be to enable the taxpayer to work or look for work. Whether an expense has such a purpose is dependent on the facts and circumstances of each particular case. These expenses can include those for providing care for a qualifying individual or individuals both in and outside the taxpayer's home.

In-home Care Expenses

In-home care expenses include costs of care provided in the taxpayer's home such as the cost of a nanny to look after a child or a housekeeper to look after an elderly parent. The payroll taxes associated with these services, as well as meals and lodging provided to the caregiver as part of their employment, may be qualifying expenses. For household services that are in part for the care of qualifying individuals and in part for other purposes, generally only the portion for the care of a qualifying individual can be applied to the credit.3

Out-of-home Care Expenses

There are different types of care provided outside the taxpayer's home that may be considered qualifying expenses for the purposes of the credit. To qualify, the care must be provided to the taxpayer's dependent child under age 13 or another qualifying person who regularly spends at least eight hours each day in the taxpayer's home (in other words, a nonchild dependent must generally live with the taxpayer even if that dependent spends the day at a care facility). This means, for example, that care provided at a live-in nursing home for a taxpayer's parent or spouse is not a qualifying expense. Common types of qualifying out-of-home care expenses include the following:

- Dependent care center: Care provided at a "dependent care center" can be considered a qualifying expense only if the center complies with all state and local regulations. A dependent care center is defined as a facility that provides care for more than six people (other than those who may reside at the facility) and receives a payment or grant for providing care services.

- Pre-K education/Before- and after-school care: Expenses for education below the kindergarten level (e.g., nursery school or preschool) may be qualifying expenses for the credit. Treasury regulations provide that expenses for education at the kindergarten level or higher do not qualify for the credit, and neither does summer school or tutoring expenses.4 However, before- or after-school care of a child in kindergarten or higher grades may be a qualifying expense.

- Day camp: Day camp may be a qualifying expense. However, overnight camp is not a qualifying expense.

- Transportation: Transportation by a care provider (i.e., not the taxpayer) to take a qualifying individual to or from a place where care is provided may be a qualifying expense. For example, the cost of a nanny driving a child to a day care center may be considered a qualifying expense.5

|

Child |

Other Dependent |

|

|

In-Home Care |

|

|

|

Outside-the-Home Care |

|

|

Source: Congressional Research Service based on information found in 26 C.F.R. §1.21.

Note: The expense must meet all other criteria, including being paid or incurred so that the taxpayer can work or look for work. Whether an expense actually qualifies for the credit will depend on the facts and circumstances of each particular case.

Rules Regarding Payments Made to Relatives Who Provide Care

Payments made to a relative for child and dependent care are generally eligible for the credit. However, payments made to the following types of relatives would not be eligible for the CDCTC.

- Taxpayer's dependent: the relative is the taxpayer's dependent (i.e., the taxpayer or spouse is eligible to claim the relative for the dependent exemption).

- Child under 19 years old: the relative is the taxpayer's child and under 19 years old (irrespective of whether they are the taxpayer's dependent).

- Spouse: the relative is the taxpayer's spouse at any time during the year.

- Parent of a qualifying child: The relative is the parent of the qualifying child for whom the expenses are incurred.6

Care Provider ID Test

Taxpayers claiming the CDCTC generally must provide the name, address, and taxpayer identification number of any individual or entity that provides care for a qualifying individual or the IRS may deny the taxpayer's claim for the credit. Taxpayer identification numbers for individuals are either Social Security numbers (SSNs) or individual taxpayer identification numbers (ITINs). Entities' taxpayer identification numbers are generally employer identification numbers (EINs). Taxpayers are only required to provide the name and address (i.e., not the ITIN) of a care provider that is a tax-exempt 501(c)(3) organization. If a care provider refuses to provide information (e.g., an individual does not wish to provide the taxpayer with their SSN), the taxpayer can generally still claim the credit if they exercise due diligence in attempting to obtain the information and keep a record of their attempt to secure this information.7

Qualifying Individual

For the purposes of the child and dependent care credit, a qualifying individual is a:

- Young child: The taxpayer's dependent child under 13 years of age. Specifically, the child must be the taxpayer's "qualifying child" for purposes of claiming the personal exemption with the additional requirement that the child be 12 years or younger when the qualifying expenses were paid or incurred. (For more information on what a "qualifying child" is for the personal exemption, see the Appendix.)

- Spouse incapable of caring for themselves: The taxpayer's spouse who is physically or mentally incapable of self-care and has lived with the taxpayer for more than half the year. Incapable of self-care means that the individual cannot care for their own hygiene or nutritional needs or requires full-time attention for their own safety or the safety of others.8

- Other dependents incapable of caring for themselves: An individual who is physically or mentally incapable of self-care (as defined above), lived with the taxpayer for more than half of the year, and is either:

- The taxpayer's dependent (i.e., the taxpayer could claim a personal exemption for the individual); or

- An individual who the taxpayer could have claimed as a dependent (for the personal exemption) except that

- He or she has gross income that equals or exceeds the personal exemption amount,

- He or she files a joint return, or

- The taxpayer (or their spouse, if filing jointly) could be claimed as a dependent on another taxpayer's return.

- Examples of individuals who may fall into this category include adult children who cannot care for themselves, as well as elderly relatives who live with the taxpayer.

The taxpayer must provide the taxpayer identification number—either a Social Security number (SSN), individual taxpayer identification number (ITIN), or adoption taxpayer identification number (ATIN)—of each qualifying individual for whom they claim the CDCTC. Failure to do so can result in the denial of the credit.

Earned Income Test

In order to claim the credit, a taxpayer (and if married, their spouse) must have earned income during the year. For taxpayers who do not work as a result of the taxpayer (or if married, their spouse) being incapable of self-care or a full-time student, special rules apply in calculating their annual earned income (see "Deemed Income in Cases Where an Individual is Incapable of Self-Care or a Full-Time Student.").

Earned income includes wages, salaries, tips, other taxable employee compensation, and net earnings from self-employment. In general only earned income that is taxable (i.e., wages, salaries, and tip income) is considered for this test. Hence nontaxable compensation like foreign earned income and Medicaid waiver payments does not count as earned income. However, taxpayers can elect to include nontaxable combat pay as earned income when claiming the credit.

Filing Status

Generally taxpayers who file their federal income taxes as single, head of household, or married filing jointly are eligible to claim the credit,9 while those who file using the status "married filing separately" are ineligible for the credit. However, in certain cases, taxpayers who use the filing status "married filing separately" may be eligible for the credit if they live apart from their spouse for more than half the year and care for a qualifying individual.10 (Spouses who are legally separated are generally not considered married for tax purposes.)

Calculating the Credit Amount

The amount of the CDCTC is calculated by multiplying the amount of qualifying expenses, after applying the dollar limits and earned income limits (discussed below), by the appropriate credit rate. Since the credit is nonrefundable, the actual amount of the credit claimed cannot exceed the taxpayer's income tax liability.

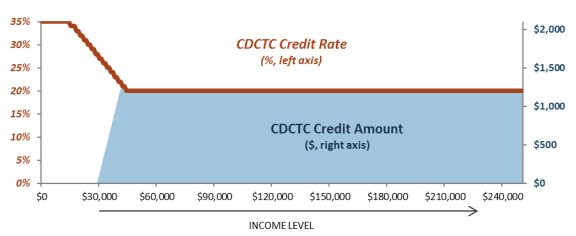

The credit rate used to calculate the credit is based on the taxpayer's adjusted gross income (AGI). The credit rate is set at a maximum of 35% for taxpayers with AGI under $15,000. The credit rate then declines by one percentage point for each $2,000 (or fraction thereof) above $15,000 of AGI, until the credit rate reaches its statutory minimum of 20% for taxpayers with AGI over $43,000. This credit rate schedule is illustrated in Table 2. The AGI brackets associated with each credit rate are not adjusted annually for inflation.

|

Maximum Statutory Credit Amount |

|||

|

Adjusted Gross Income (AGI) |

Credit Rate |

One Child |

Two or More Children |

|

$0-$15,000 |

35% |

$1,050 |

$2,100 |

|

$15,000 - $17,000 |

34% |

$1,020 |

$2,040 |

|

$17,000 - $19,000 |

33% |

$990 |

$1,980 |

|

$19,000 - $21,000 |

32% |

$960 |

$1,920 |

|

$21,000 - $23,000 |

31% |

$930 |

$1,860 |

|

$23,000 - $25,000 |

30% |

$900 |

$1,800 |

|

$25,000 - $27.000 |

29% |

$870 |

$1,740 |

|

$27,000 - $29,000 |

28% |

$840 |

$1,680 |

|

$29,000 - $31,000 |

27% |

$810 |

$1,620 |

|

$31,000 - $33,000 |

26% |

$780 |

$1,560 |

|

$33,000 - $35,000 |

25% |

$750 |

$1,500 |

|

$35,000 - $37,000 |

24% |

$720 |

$1,440 |

|

$37,000 - $39,000 |

23% |

$690 |

$1,380 |

|

$39,000 - $41,000 |

22% |

$660 |

$1,320 |

|

$41,000 - $43,000 |

21% |

$630 |

$1,260 |

|

$43,000+ |

20% |

$600 |

$1,200 |

Source: IRS Publication 503 and Internal Revenue Code (IRC) §21.

The maximum amount of expenses that can be multiplied by the credit rate is $3,000 if the taxpayer has one qualifying individual and $6,000 if the taxpayer has two or more qualifying individuals. These amounts are not adjusted annually for inflation. For taxpayers with two or more qualifying individuals, the maximum expense threshold is per taxpayer irrespective of actual child and dependent care expenses of each qualifying individual. Hence, if a taxpayer has two qualifying individuals, and they have incurred no qualifying expenses for one individual and $6,000 for the other, they can claim a credit for up to $6,000 of qualifying expenses.

Even though the credit formula—due to the higher credit rate—is more generous toward lower-income taxpayers, many receive little or no credit since the credit is nonrefundable, as illustrated in Figure 1

Limitations Based on Earned Income

In addition to the maximum dollar amount of qualifying expenses, as previously discussed, there are additional limits on the amount of annual work-related expenses used to calculate the credit. Specifically, qualifying expenses used to claim the credit cannot be more than

- the taxpayer's earned income for the year (for unmarried taxpayers) or

- the lower-earning spouse's earned income for the year (for married taxpayers).

For example, if an unmarried taxpayer had two qualifying individuals and $6,000 of qualifying expenses but $4,000 of earned income, the maximum amount of expenses that could be applied toward the credit would be $4,000.

If an individual (either an unmarried taxpayer or each spouse among married taxpayers) does not have earnings for each month of a calendar year, they can calculate their total earned income for the year by summing up their earnings for those months in which they do have earned income. (Among married taxpayers, both spouses may need to calculate their earned income for the year to determine which spouse is the lower-earning spouse. Total expenses cannot be more than the earned income of the lower-earning spouse.) For example, if an unmarried taxpayer (or the lower-earning spouse of a two-earner couple) earned $500 for three months of the year, and did not work the remaining nine months of the year, their earned income for the purposes of the earned income limitation would be $1,500 and they could not use more than $1,500 of child and dependent care when calculating the credit.

Deemed Income in Cases Where an Individual is Incapable of Self-Care or a Full-Time Student.

If an individual (either an unmarried taxpayer or each spouse among married taxpayers) has little or no earnings for each month of a calendar year, they will calculate their earned income differently. For months in which an individual does not have earnings and is also incapable of self-care or a full-time student, their earned income for that month equals a "deemed" amount (instead of equaling zero). Specifically, their earned income is "deemed" to be $250 per month if they have one qualifying individual or $500 per month if they have two or more qualifying individuals.11 If an individual—either an unmarried taxpayer, or if married, the lower-earning spouse of a two-earner couple—is either a full-time student or not able to care for themselves for the entire year, they may be eligible (depending on their actual expenses) to apply the maximum amount of expenses when calculating the credit. Specifically, $250 and $500 multiplied by 12 months will result in an annual amount of earned income of $3,000 if they have one qualifying individual or $6,000 if they have two or more qualifying individuals—the statutory maximum amount of qualifying expenses for the credit.

Among a married couple, one spouse in any given month can be "deemed" to have earned income ($250 per month for one qualifying individual or $500 per month for two or more qualifying individuals) as a result of being incapable of self-care or being a full-time student. This implies that if both spouses are incapable of self-care or full-time students simultaneously for every month in a year, the couple will ultimately be ineligible for the credit. In this scenario only one spouse would be considered as having earned income, and hence the couple would be ineligible for the credit.

Exclusion for Employer-Sponsored Child and Dependent Care Benefits

In addition to the CDCTC, workers can exclude from their wages up to $5,000 of employer-sponsored child and dependent care benefits.12 Since the value of these benefits is excluded from wages, it is not subject to income or payroll taxes.

Employer-sponsored child and dependent care benefits can be provided in various forms, including

- direct payments by an employer to a child care or adult day care provider,

- on-site child or dependent care offered by an employer,

- employer reimbursement of employee child care costs, and

- flexible spending accounts (FSAs) that allow employees to set aside a portion of their salary on a pretax basis (i.e., under a "cafeteria plan") to be used for qualifying expenses.

The eligibility rules and definitions of the exclusion are similar to those of the credit. However, there is one key difference. Specifically, the $5,000 limit applies irrespective of the number of qualifying individuals. For example, a family with one qualifying child or two qualifying children can both set aside a maximum $5,000 on a pretax basis for child care. With the child and dependent care credit there are separate limits based on the number of qualifying individuals ($3,000 for one qualifying individual, $6,000 for two or more qualifying individuals).13 In addition, married taxpayers who file their returns as married filing separately are eligible to benefit from this exclusion, while they are ineligible for the credit.

Interaction Between the CDCTC and Exclusion for Employer-Sponsored Child and Dependent Care

Taxpayers can claim both the exclusion and the tax credit but not for the same out-of-pocket child and dependent care expenses. In addition, for every pretax (i.e., excluded) dollar of employer-sponsored child and dependent care, the taxpayer must reduce the maximum amount of qualifying expenses for the credit (up to $3,000 for one child, $6,000 for two or more children). For example, if a family had one child, $10,000 in annual child care expenses, and contributed $5,000 annually to their employer's FSA, the family could not claim the CDCTC.14 The amount of pretax dollars in the FSA ($5,000) would eliminate the maximum amount of expenses that could be applied to the credit ($3,000). If in the same year, the family had a second child, and all else remained the same, they could claim $5,000 tax-free through their FSA and claim the remaining allowable expense of $1,000 ($6,000 max for two or more children minus $5,000 in the FSA) for the CDCTC.

Data on the CDCTC

The aggregate data for the child and dependent care credit indicate several key aspects of this tax benefit.

- Income level of CDCTC claimants: Middle- and upper-middle-income taxpayers claim the majority of tax credit dollars.

- Average credit amount: At most income levels the average credit amount is between $500 and $600. Lower-income taxpayers receive less than the average amount.

- Average credit amount over time: Over the past 30 years, the average real (i.e., adjusted for inflation) credit amount per taxpayer has steadily declined and lost about one-third of its value.

- Types of qualifying individuals claimed for the credit: While the credit is available for the care expenses of nonchild dependents (disabled family members or elderly parents), the credit is used almost exclusively for the care of children under 13 years old.

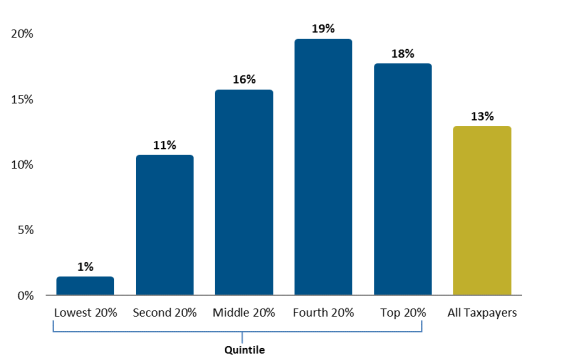

- Percentage of taxpayers with children that claim the CDCTC: While the credit is claimed almost exclusively for the care of children, on average 13% of taxpayers with children claim the credit. This participation rate is significantly lower for lower-income taxpayers.

Income Level of CDCTC Claimants/Average Credit Amount

The CDCTC tends to be claimed by middle- and upper-middle-income taxpayers. Comparatively few claimants are low-income or very high-income, as illustrated in Table 3. For most taxpayers, the average credit amount is between $500 and $600, although low-income taxpayers that do claim the CDCTC tend to receive a smaller tax credit. Few lower-income taxpayers benefit from the CDCTC, since the credit is nonrefundable. As previously discussed, a nonrefundable credit is limited to the taxpayer's income tax liability. Hence, taxpayers with little to no income tax liability—including low-income taxpayers—receive little to no benefit from nonrefundable credits like the CDCTC.

For some taxpayers, especially higher-income taxpayers, the amount of their CDCTC will be affected by the amount of tax-free employer-sponsored child care they receive. If a taxpayer's marginal tax rate is greater than the applicable credit rate, the taxpayer will receive a larger tax savings from claiming the exclusion rather than the credit (in addition, the exclusion lowers their payroll taxes). For example, $100 of employer-sponsored child care saved in an FSA would lower a taxpayer's income tax bill by $35 if they were in the 35% tax bracket.15 The tax savings associated with applying that $100 to the CDCTC would, by contrast, be $20. Hence, if employer-sponsored child care is offered by their employer, a taxpayer may claim this benefit first and apply any remaining eligible expenses (if applicable)16 toward the credit, lowering their credit amount in comparison to if the exclusion was not available.

Table 3. Distribution of Taxpayers and Credit Dollars

and Average Credit Amount by Adjusted Gross Income (AGI), 2014

|

Adjusted Gross Income (AGI) |

% of All Returns |

% of All Returns Claiming CDCTC |

% of Aggregate CDCTC Dollars |

Average Credit Amount |

|

$0-under $15K |

24.5% |

0.1% |

<0.1% |

$83 |

|

$15K-under $25K |

14.4% |

7.0% |

4.2% |

$331 |

|

$25K-under $50K |

23.5% |

24.8% |

26.3% |

$587 |

|

$50K-under $75K |

13.1% |

16.3% |

15.7% |

$533 |

|

$75K-under $100K |

8.6% |

15.0% |

15.9% |

$584 |

|

$100K-under $200K |

11.8% |

27.8% |

28.7% |

$572 |

|

$200K-under $500K |

3.4% |

7.8% |

7.9% |

$559 |

|

$500K+ |

0.8% |

1.2% |

1.3% |

$607 |

|

All Taxpayers |

100.0% |

100.0% |

100.0% |

$553 |

Source: IRS Statistics of Income (SOI) 2014, Table 3.3.

Average Credit Amount Over Time

|

1976: P.L. 94-455 enacted the nonrefundable child and dependent care credit.17 The credit formula was 20% of eligible expenditures subject to a maximum level of expenditures of $2,000 for one qualifying individual and $4,000 for two or more qualifying individuals. These amounts were not adjusted for inflation. 1981: P.L. 97-34 created the current "sliding-scale" credit rate whereby the credit rate decreases as income increases. The sliding scale began at 30% for taxpayers with adjusted gross income of $10,000 or less, with the rate reduced by one percentage point for each $2,000 (or fraction thereof) above $10,000 until the lowest rate of 20% was reached at $28,000 of income. The law also increased the maximum expenditures from $2,000 to $2,400 for one qualifying individual and from $4,000 to $4,800 for two or more qualifying individuals.18 The law also enacted the exclusion for employer-sponsored child and dependent care. 1986: P.L. 99-514 limited the dollar amount of the exclusion to $5,000 per taxpayer. 1988: P.L. 100-485 created a dollar-for-dollar reduction in the amount of expenses eligible for the CDCTC for amounts excluded under an employer-sponsored dependent care assistance program (see "Interaction Between the CDCTC and Exclusion for Employer-Sponsored Child and Dependent Care") 2001: P.L. 107-16 modified the sliding scale credit rate. The top credit rate was increased from 30% to 35% and the income level for this credit rate was increased from $10,000 to $15,000. The law also increased the maximum expenditures from $2,400 to $3,000 for one qualifying individual and from $4,800 to $6,000 for two or more qualifying individuals. These amounts were not indexed for inflation. These were temporary changes scheduled to expire at the end of 2010. 2010: P.L. 111-312 extended the 2001 changes for 2011 and 2012. 2012: P.L. 112-240 made the 2001 changes permanent. |

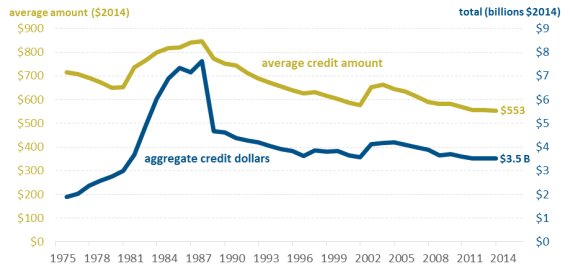

The CDCTC was enacted in 1976. Subsequent legislative changes increased the size of the credit by increasing the maximum amount of allowable expenses and the credit rate (see Figure 2).

Between 1976 and 1988, the average credit amount and aggregate amount of the credit steadily increased, as illustrated in Figure 3. Beginning in 1989, both the average and aggregate credit amount began to decline, with a sharp drop in the aggregate amount claimed. This decline over such a short time period may be due to measures adopted by the IRS to reduce improper claims of tax benefits, as well as legislative changes. First, beginning in 1987, taxpayers were required to provide the Social Security numbers (SSNs) of dependents on their federal income tax returns.19 Second, beginning in 1989, taxpayers had to provide the caregiver's taxpayer ID number (generally for individuals, their SSNs).20 According to one IRS researcher, "What probably happened in most cases is that people were paying their babysitter off the books, and their babysitter would not provide their Social Security numbers or go on the books, so the family had to choose between finding a new babysitter, or giving up the credit."21 Finally, in 1988, Congress enacted a provision as part of P.L. 100-485 (see Figure 2) that required taxpayers to reduce the amount of expenses applied to the credit by amounts received under the exclusion. This may have resulted in a substantial reduction in the amount of expenses many taxpayers applied toward the credit, and hence a smaller credit.

Since 1988, the real average value of the CDCTC has steadily fallen (see Figure 3). This may be driven by several factors. First, as previously discussed, the parameters of the credit, including the maximum amount of qualifying expenses and income brackets for each applicable credit rate (see Table 2) are not indexed for inflation. The last time the credit rate and maximum level of expenses was increased was in 2001 as part of the Economic Growth and Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2001 (EGTRRA; P.L. 107-16 ). Before EGTRRA the parameters of the credit had not been increased since 1981 (see Figure 2). If the credit as enacted in 1976 had been adjusted annually for inflation, the $800 maximum credit amount in 1976 would have equaled more than $3,200 in 2014. Hence, inflation has eroded a substantial amount of the value of the credit.

Types of Qualifying Individuals Claimed for the Credit

Administrative data from the Internal Revenue Service, summarized in Table 4, indicate that the CDCTC is used primarily for the care expenses of children under 13 years old.

Table 4. Distribution of Taxpayers and Credit Dollars by

Age of Qualifying Individuals Claimed for CDCTC, 2014

|

Tax Returns |

Total Credit Dollars |

|||

|

Age of Qualifying Individual(s) |

Number |

Percent |

Billions $ |

Percent |

|

Exclusively under 13 years old |

6,058,313 |

95.5% |

$3.35 |

95.6% |

|

Exclusively 13 years old or older |

158,813 |

2.5% |

$0.07 |

2.0% |

|

Mix of over and under 13 years old |

123,757 |

2.0% |

$0.08 |

2.4% |

|

Total |

6,340,882 |

100.0% |

$3.50 |

100.0% |

Source: Internal Revenue Service, Statistics of Income (SOI).

Few taxpayers claim the CDCTC for older dependents. This may be a result of several factors. First, most dependents are children. For example, in 2014, over 83 million dependent exemptions were claimed for children, while approximately 13 million were claimed for older dependents (including parents).22 Second, the definition of qualifying expenses excludes many expenses incurred for older dependents. For example, if older dependents are being cared for by a stay-at-home taxpayer, any expenses incurred for their care will not be considered qualifying expenses (since the caregiver is not considered to be working or looking for work). In addition, eldercare expenses, like nursing home expenses, are not considered qualifying expenses for the CDCTC since the individual being cared for is not living with the taxpayer for at least eight hours each day (see "Qualifying Expenses").

Percentage of Taxpayers with Children Who Claim the CDCTC

Data from the Tax Policy Center (TPC) indicate that on average about 13% of taxpayers with children claim the child and dependent care credit, as illustrated in Figure 4.23 A greater proportion of higher-income taxpayers with children claim the credit than lower-income taxpayers. One possible explanation for why relatively few families with children claim the credit is that they do not have childcare expenses (perhaps because their children are older). Another possible explanation is that care expenses that are incurred are not considered qualifying expenses for the credit. For example, families with a stay-at-home parent would generally be ineligible for the CDCTC. In addition, families that pay an older child to look after a younger child after school would not be considered qualifying expenses. Finally, families eligible for the exclusion and with only one child may benefit more from the exclusion and simply not claim the credit.

|

Figure 4. Percentage of Taxpayers with Children Who Claim the CDCTC, 2016 By Income Quintile |

|

|

Source: Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center Microsimulation Model (version 0516-1). Notes: Each quintile contains 20% of the population ranked by expanded cash income (ECI).24 |

Fewer lower-income families with children benefit from the CDCTC, since the credit is nonrefundable. A nonrefundable credit is limited to the taxpayer's income tax liability. Taxpayers with little to no income tax liability, including low-income taxpayers, hence receive little to no benefit from nonrefundable credits.

Data on the Exclusion of Employer-Sponsored Child and Dependent Care

Administrative data from the IRS on the exclusion of employer-sponsored child and dependent care—comparable to the data on CDCTC—are unavailable. However, survey data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics indicate that about 40% of employees have access to child and dependent care flexible spending accounts, while 11% have access to employer-sponsored childcare.25 (Access means that these accounts are available to workers for their use. However, actual use of these accounts may be lower than these access rates.) The survey also found that availability of these benefits differed based on a variety of factors including the average wage paid to the employee and size of employer, as summarized in Table 5. Overall, the data indicate that these benefits are more widely available to more highly compensated employees at larger establishments.

|

Access to Dependent Care Flexible Spending Account (FSA)a |

Access to Employer- Provided Child Care |

|

|

Average Wageb |

||

|

Lowest 10% |

11% |

2% |

|

Lowest 25% |

18% |

4% |

|

Second 25% |

38% |

8% |

|

Third 25% |

49% |

13% |

|

Highest 25% |

61% |

19% |

|

Highest 10% |

65% |

22% |

|

Size of Employer |

||

|

1-49 workers |

19% |

4% |

|

50-99 workers |

30% |

7% |

|

100-499 workers |

48% |

10% |

|

500 workers or more |

69% |

24% |

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, National Compensation Survey: Employee Benefits in the United States, March 2016, Tables 40 and 41.

Notes: These results are for civilian employees only.

a. These data reflect access to FSAs provided as part of a Section 125 cafeteria plan.

b. Surveyed occupations are classified into wage categories based on the average wage for the occupation which may include workers with earnings both above and below the threshold.

Appendix. What Is a "Dependent" for the Personal Exemption?

The personal exemption allows taxpayers to subtract a fixed amount from taxable income per qualifying dependent. In 2017, this amount is $4,050; it is set to rise to $4,150 in 2018.

For the purposes of the dependent exemption, an individual is either (1) a qualifying child or (2) a qualifying relative. There are several tests to determine whether an individual is a taxpayer's qualifying child or relative, outlined in Table A-1.

|

Qualifying Child |

Qualifying Relative |

|

Relationship: The child is the taxpayer's son, daughter, stepchild, foster child, brother, sister, half-brother, half-sister, stepbrother, stepsister, or a descendant of any of them. |

1. Member of Household or Relationship: The individual must either: (a) Be a member of the taxpayer's household for the entire year, or (b) If they don't live with the taxpayer, be a relative of the taxpayer.a |

|

Residence: The child must have lived with the taxpayer for more than half the year. |

Gross Income Test: The individual's gross income must be less than the personal exemption amount ($4,050 in 2017). |

|

Age: The child is either (a) under 19 years old at the end of the year; (b) under 24 years old at the end of the year and a full-time student; (c) any age if permanently and totally disabled. |

Age: None |

|

Support: The child must not have provided more than half of his or her own support for the year. |

Support: The taxpayer must provide more than half of the qualifying individuals support for the year. |

|

Joint Return: The child must not be filing a joint return for the year (unless that joint return is filed only to claim a refund of withheld income tax or estimated tax paid). |

Not a qualifying child: The individual cannot be claimed as a qualifying child by any taxpayer. |

Source: IRS Publication 501 and Internal Revenue Code (IRC) §152.

a. The individual is related to the taxpayer as their son, daughter, stepchild, foster child, brother, sister, half-brother, half-sister, stepbrother, stepsister, or a descendant of any of them; father, mother, grandparent, or other direct ancestor; stepfather or stepmother; son or daughter of the taxpayer's brother or sister; son or daughter of the taxpayer's half-brother or half-sister; the taxpayer's aunt or uncle, the taxpayer's son-in-law, daughter-in-law, father-in-law, mother-in-law, brother-in-law, or sister-in-law.