Source: Eurostat, October 2017.

With the easing of nuclear-related sanctions on Iran by the United States, European Union and United Nations under the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), signed on July 14, 2015, many foreign firms have begun to resume business with Iran. However, on October 13, 2017, President Trump announced he would not issue the certification that sanctions relief is "proportionate" to the measures taken by Iran to terminate its nuclear program. This decision has raised questions over the possible reimposition of U.S. economic sanctions. The EU, which views the JCPOA as a binding international commitment, is threatening to take action to protect its firms from reimposed secondary sanctions. No matter the actions of EU governments, EU companies might base their responses on a calculation of their economic interests in Iran versus risks to their position in U.S. markets.

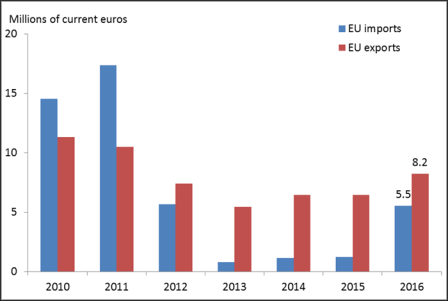

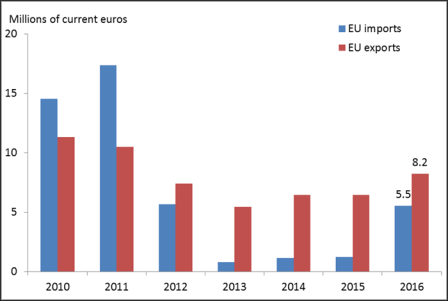

EU sanctions relief, coupled with the lifting of U.S. secondary sanctions under the JCPOA, paved the way for increased trade and foreign direct investment in Iran. The EU lifted its bans on Iranian oil and gas imports and trade in other sectors, and Iran's use of the SWIFT financial messaging services system, among other restrictions. Before the escalation of sanctions, in 2010, the EU was Iran's top trading partner, accounting for nearly a quarter of Iran's total goods trade; in 2015, the EU accounted for 8%, replaced by China (25%), the United Arab Emirates (17%), and Turkey (10%), according to International Monetary Fund data. Following adoption of the JCPOA, EU imports from Iran rebounded in 2016 with 347% growth compared to 2015, driven by resumed purchases of fuels and mining products; though trade remains short of pre-sanctions levels (Figure 1). EU exports to Iran expanded by 28%, led by exports in machinery and transport equipment and chemicals.

In early 2017, Iran delivered its largest monthly shipments of crude to Europe since the end of 2011. While Asia has been a top buyer of Iranian energy, National Iranian Oil Company (NIOC) crude sales to Europe are rising as Iran seeks to recapture market share; Europe accounted for 34% of NIOC sales through July 2017, compared to 31% at the end of 2016.

|

|

Source: Eurostat, October 2017. |

Since the easing of sanctions in January 2016, several EU multinational corporations have announced new investments including in the manufacturing, energy, and auto sectors.

At the same time, major European financial institutions and other banks have been cautious about engaging in transactions with Iran. Uncertainty regarding possible reimposition of the waived U.S. sanctions and fear of violating those U.S. sanctions that remain in place are among cited reasons for such reticence. The Treasury Department has taken a number of enforcement actions for sanctions violations and evasion, resulting in hefty civil fines paid by some major European banks.

How risk averse foreign companies will be with regard to expanding activities in Iran given continued uncertainty over the JCPOA is an open question. U.S. sanctions can have a broad chilling effect on economic activity when firms are faced with losing access to the U.S. market. Moreover, some analysts view EU options as increasingly constrained given that "European companies now have far more assets exposed to U.S. regulators, who could retaliate against them, or force them to pick between the Iranian and U.S. markets."

U.S. sanctions that target secondary activities became prominent in U.S. legislation from the early 1990s. The EU has opposed that strategy from the onset and has sometimes resorted to regulatory action and dispute settlement at the World Trade Organization (WTO) to shield its firms.

Blocking Statutes. In response to U.S. sanctions on Cuba, Iran, and Libya, the EU adopted Council Regulation (EC) 2271/96 in 1996 to protect "against the effects of extra-territorial application of legislation adopted by a third country." It remains in force. Key features include: prohibiting compliance (whether directly or through a subsidiary) with specified U.S. laws; prohibiting recognition or compliance with court judgments outside the EU that give effect to U.S. sanctions; and entitlement to recover any damages incurred as a result of noncompliance with U.S. sanctions. An annex lists U.S. laws and regulations subject to the measure (including the Iran [and Libya] Sanctions Act of 1996, P.L. 104-172)—amendments to the annex would be required to include subsequent U.S. laws pertaining to Iran. The regulation also compels EU member states to determine "effective, proportional and dissuasive" sanctions in the event of a breach of the provisions. Member states are responsible for implementation; in practice, there have been few cases of enforcement. In one case, the Austrian government sought to penalize the Austrian Bank Bawag for violating the blocking regulation, after the bank closed accounts of Cuban nationals to comply with the Cuban Liberty and Democratic Solidarity Act of 1996 (P.L. 104-114).

WTO Dispute Settlement. In 1996, the EU also initiated a dispute under WTO procedures to challenge certain provisions of U.S. sanctions against Cuba as inconsistent with U.S. obligations. The United States claimed its policies would be defensible under the broad "national security" exception of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT). The case was ultimately withdrawn in April 1998, after the United States and EU reached a negotiated compromise that effectively exempted the EU from key contested provisions. The EU reserved the right to re-initiate the case if the United States took adverse action against EU firms. The EU could file a complaint in the wake of reimposed sanctions on Iran; however, WTO disputes can take several years to resolve. Moreover, cases involving claims of "national security" have rarely been litigated at the WTO—creating an incentive for a negotiated settlement.